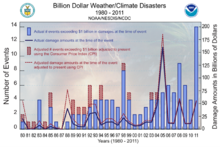

Total extreme weather cost and number of events costing more than $1 billion in the United States from 1980 to 2011.

This article is about the economics of climate change mitigation. Mitigation of climate change involves actions that are designed to limit the amount of long-term climate change. Mitigation may be achieved through the reduction of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions or through the enhancement of sinks that absorb GHGs, for example forests.

Definitions

In

this article, the phrase “climate change” is used to describe a change

in the climate, measured in terms of its statistical properties, e.g.,

the global mean surface temperature. In this context, “climate”

is taken to mean the average weather. Climate can change over period of

time ranging from months to thousands or millions of years. The

classical time period is 30 years, as defined by the World Meteorological Organization. The climate change referred to may be due to natural causes, e.g., changes in the sun's output, or due human activities, e.g., changing the composition of the atmosphere. Any human-induced changes in climate will occur against the “background” of natural climatic variations.

Public good issues

The atmosphere is an international public good and GHG emissions are an international externality (Goldemberg et al., 1996:,21, 28, 43). Each individual's or country's welfare, Uj, is a function of its own consumption, Cj, and the quality of the atmosphere, A, such that Uj(Cj,A). A change in the quality of the atmosphere, A,

does not affect the welfare of all individuals and countries equally.

In other words, some individuals and countries may benefit from climate

change, but others may lose out.

Heterogeneity

GHG emissions are unevenly distributed around the world, as are the potential impacts of climate change (Toth et al., 2001:607).

Nations with higher than average emissions that face potentially small

negative/positive climate change impacts have little incentive to reduce

their emissions. Nations with relatively low levels of emissions that

face potentially large negative climate change impacts have a large

incentive to reduce emissions. Nations that avoid mitigation can benefit

from free-riding on the actions of others, and may even enjoy gains in trade and/or investment (Halsnæs et al., 2007:127).

The unequal distribution of benefits from mitigation, and the potential

advantages of free-riding, make it difficult to secure an international

agreement to reduce emissions.

Intergenerational transfers

Mitigation of climate change can be considered a transfer of wealth from the present generation to future generations (Toth et al.., 2001:607).

The amount of mitigation determines the composition of resources (e.g.,

environmental or material) that future generations receive. Across

generations, the costs and benefits of mitigation are not equally

shared: future generations potentially benefit from mitigation, while

the present generation bear the costs of mitigation but do not directly

benefit (ignoring possible co-benefits, such as reduced air pollution).

If the current generation also benefitted from mitigation, it might lead

them to be more willing to bear the costs of mitigation.

Irreversible impacts and policy

Emissions of carbon dioxide (CO2) might be irreversible on the time scale of millennia (Halsnæs et al., 2007).

There are risks of irreversible climate changes, and the possibility of

sudden changes in climate. On the other hand, these effects are also

true of mitigation efforts. Investments

made in long-lived, large-scale low-emission technologies are

essentially irreversible. If the scientific basis for these investments

turns out to be wrong, they would become "stranded" assets.

Additionally, the costs of reducing emissions may change over time in a non-linear fashion.

From an economic perspective, as the scale of private sector investment in low-carbon technologies increases, so do the risks. Uncertainty over future climate policy

decisions makes investors reluctant to undertake large-scale investment

without upfront government support. The later section on finance discusses how risk affects investment in developing and emerging economies.

Sustainable development

Solow (1992) (referred to by Arrow, 1996b, pp. 140–141) defined sustainable development as allowing for reductions in exhaustible resources

so long as these reductions are adequately offset by increases in other

resources. This definition implicitly assumes that resources can be

substituted, a view which is supported by economic history. Another view

is that reductions in some exhaustible resources can only be partially

made up for by substitutes. If true, this might mean then some assets need to be preserved at all costs.

In many developing countries, Solow's definition might not be

viewed as being acceptable, since it could place a constraint on their

ambitions for development. A remedy for this would be for developed

countries to pay all the costs of mitigation, including costs in

developing countries. This solution is suggested by both Rawlsian and utilitarian constructs of the social welfare function. These functions are used to assess the welfare impacts on all individuals of climate change and related policies (Markandya et al., 2001, p. 460). The Rawlsian approach concentrates on the welfare of the worst-off in society, whereas the utilitarian approach is a sum of utilities (Arrow et al., 1996b, p. 138).

It might be argued that since such redistributions of resources

are not observed now, why would either Rawlsian or utilitarian

constructs be appropriate for climate change (Arrow et al.,

1996b, p. 140)? A possible response to this would point to the fact that

in the absence of government intervention, market rates of

redistribution will not equal social rates.

Emissions and economic growth

Economic growth is a key driver of CO2 emissions (Sathaye et al., 2007:707). As the economy expands, demand for energy and energy-intensive goods increases, pushing up CO2

emissions. On the other hand, economic growth may drive technological

change and increase energy efficiency. Economic growth may be associated

specialization in certain economic sectors. If specialization is in

energy-intensive sectors, then there might be a strong link between

economic growth and emissions growth. If specialization is in less

energy-intensive sectors, e.g., the services sector, then there might be

a weak link between economic growth and emissions growth. Unlike

technological change or energy efficiency improvements, specialization

in high or low energy intensity sectors does not affect global

emissions. Rather, it changes the distribution of global emissions.

Much of the literature focuses on the "environmental Kuznets curve" (EKC) hypothesis, which posits that at early stages of development, pollution per capita and GDP per capita

move in the same direction. Beyond a certain income level, emissions

per capita will decrease as GDP per capita increase, thus generating an

inverted-U shaped relationship between GDP per capita and pollution.

Sathaye et al.. (2007) concluded that the econometrics

literature did not support either an optimistic interpretation of the

EKC hypothesis - i.e., that the problem of emissions growth will solve

itself - or a pessimistic interpretation - i.e., that economic growth is

irrevocably linked to emissions growth. Instead, it was suggested that

there was some degree of flexibility between economic growth and

emissions growth.

Policies that impact emissions

Price signals and subsidies

In developed countries, energy costs are low and heavily subsidized, whereas in developing countries, the poor pay high costs for low-quality services. Bashmakov et al..

(2001:410) commented on the difficulty of measuring energy subsidies,

but found some evidence that coal production subsidies had declined in

several developing and OECD countries.

Structural market reforms

Market-orientated reforms, as undertaken by several countries in the 1990s, can have important effects on energy use, energy efficiency, and therefore GHG emissions. In a literature assessment, Bashmakov et al.. (2001:409) gave the example of China, which has made structural reforms with the aim of increasing GDP.

They found that since 1978, energy use in China had increased by an

average of 4% per year, but at the same time, energy use had been

reduced per unit of GDP.

Liberalization of energy markets

Liberalization and restructuring of energy markets has occurred in several countries and regions, including Africa, the EU, Latin America, and the US.

These policies have mainly been designed to increase competition in the

market, but they can have a significant impact on emissions. Bashmakov et al..

(2001:410) concluded that structural reform of the energy sector could

not guarantee a shift towards less carbon-intensive power generation.

Reform could, however, allow the market to be more responsive to price signals placed on emissions.

Climate and other environmental policies

National

- Regulatory standards: These set technology or performance standards, and can be effective in addressing the market failure of informational barriers (Bashmakov et al., 2001:412). If the costs of regulation are less than the benefits of addressing the market failure, standards can result in net benefits.

- Emission taxes and charges: an emissions tax requires domestic emitters to pay a fixed fee or tax for every tonne of CO2-eq GHG emissions released into the atmosphere (Bashmakov et al., 2001:413). If every emitter were to face the same level of tax, the lowest cost way of achieving emission reductions in the economy would be undertaken first. In the real world, however, markets are not perfect, meaning that an emissions tax may deviate from this ideal. Distributional and equity considerations usually result in differential tax rates for different sources.

- Tradable permits: Emissions can be limited with a permit system (Bashmakov et al., 2001:415). A number of permits are distributed equal to the emission limit, with each liable entity required to hold the number of permits equal to its actual emissions. A tradable permit system can be cost-effective so long as transaction costs are not excessive, and there are no significant imperfections in the permit market and markets relating to emitting activities.

- Voluntary agreements: These are agreements between government and industry (Bashmakov et al., 2001:417). Agreements may relate to general issues, such as research and development, but in other cases, quantitative targets may be agreed upon. An advantage of voluntary agreements are their low transaction costs. There is, however, the risk that participants in the agreement will free ride, either by not complying with the agreement or by benefitting from the agreement while bearing no cost.

- Informational instruments: According to Bashmakov et al.. (2001:419), poor information is recognized as a barrier to improved energy efficiency or reduced emissions. Examples of policies in this area include increasing public awareness of climate change, e.g., through advertising, and the funding of climate change research.

- Environmental subsidies: A subsidy for GHG emissions reductions pays entities a specific amount per tonne of CO2-eq for every tonne of GHG reduced or sequestered (Bashmakov et al., 2001:421). Although subsidies are generally less efficient than taxes, distributional and competitiveness issues sometimes result in energy/emission taxes being coupled with subsidies or tax exceptions.

- Research and development policies: Government funding of research and development (R&D) on energy has historically favored nuclear and coal technologies. Bashmakov et al.. (2001:421) found that although research into renewable energy and energy-efficient technologies had increased, it was still a relatively small proportion of R&D budgets in the OECD.

- Green power: The policy ensures that part of the electricity supply comes from designated renewable sources (Bashmakov et al., 2001:422). The cost of compliance is borne by all consumers.

- Demand-side management: This aims to reduce energy demand, e.g., through energy audits, labelling, and regulation (Bashmakov et al., 2001:422).

According to Bashmakov et al.. (2001:422), the most effective

and economically efficient approach of achieving lower emissions in the

energy sector is to apply a combination of market-based instruments

(taxes, permits), standards, and information policies.

International

Kyoto Protocol

The Kyoto Protocol is an international treaty designed to reduce emissions of GHGs. The Kyoto treaty was agreed in 1997, and is a protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change

(UNFCCC), which had previously been agreed in 1992. The Kyoto Protocol

sets legally-blinding emissions limitations for developed countries

("Annex I Parties") out to 2008-2012. The US has not ratified the Kyoto Protocol, and its target is therefore non-binding. Canada has ratified the treaty, but withdrew in 2011.

The Kyoto treaty is a "cap-and-trade" system of emissions trading, which includes emissions reductions in developing countries ("non-Annex I Parties") through the Clean Development Mechanism (CDM). The economics of the Kyoto Protocol is discussed in Views on the Kyoto Protocol and Flexible mechanisms#Views on the flexibility mechanisms. Cost estimates for the treaty are summarized at Kyoto Protocol#Cost estimates. Economic analysis of the CDM is available at Clean Development Mechanism.

To summarize, the caps agreed to in Kyoto's first commitment period (2008-2012) have turned out to be too weak. There are a large surplus of emissions allowances in the former-Soviet economies ("Economies-in-Transition" - EITs), while several other OECD countries have a deficit, and are not on course to meet their Kyoto targets (see Kyoto Protocol#Annex I Parties with targets).

Because of the large surplus of allowances, full trading of Kyoto

allowances would likely depress the price of the permits near to zero. Some of the surplus allowances have been bought from the EITs, but overall little trading has taken place. Countries have mainly concentrated on meeting their targets domestically, and through the use of the CDM.

Some countries have implemented domestic energy/carbon taxes (see carbon tax

for details) and emissions trading schemes (ETSs). The individual

articles on the various ETSs contain commentaries on these schemes.

A number of analysts have focussed on the need to establish a

global price on carbon in order to reduce emissions cost-effectively. The Kyoto treaty does not set a global price for carbon.

As stated earlier, the US is not part of the Kyoto treaty, and is a

major contributor to global annual emissions of carbon dioxide. Additionally, the treaty does not place caps on emissions in developing countries. The lack of caps for developing countries was based on equity (fairness) considerations. Developing countries, however, have undertaken a range of policies to reduce their emissions domestically. The later Cancún agreement, agreed under the UNFCCC, is based on voluntary pledges rather than binding commitments.

The UNFCCC has agreed that future global warming should be limited to below 2 °C relative to the pre-industrial temperature. Analyses by the United Nations Environment Program and International Energy Agency suggest that current policies (as of 2011) are not strong enough to meet this target.

Other policies

- Regulatory instruments: This could involve the setting of regulatory standards for various products and processes for countries to adopt. The other option is to set national emission limits. The second option leads to inefficiency because the marginal costs of abatement differs between countries (Bashmakov et al.., 2001:430).

Initiatives such as the EU "cap and trade" system have also been implemented.

- Carbon taxes: This would offer a potentially cost-effective means of reducing CO2 emissions. Compared with emissions trading, international or harmonized (where each country keeps the revenue it collects) taxes provide greater certainty about the likely costs of emission reductions. This is also true of a hybrid policy (see the article carbon tax) (Bashmakov et al.., 2001:430).

Efficiency of international agreements

For the purposes of analysis, it is possible to separate efficiency from equity (Goldemberg et al., 1996, p. 30).

It has been suggested that because of the low energy efficiency in many

developing countries, efforts should first be made in those countries

to reduce emissions. Goldemberg et al. (1996, p. 34) suggested a number of policies to improve efficiency, including:

- Property rights reform. For example, deforestation could be reduced through reform of property rights.

- Administrative reforms. For example, in many countries, electricity is priced at the cost of production. Economists, however, recommend that electricity, like any other good, should be priced at the competitive price.

- Regulating non-greenhouse externalities. There are externalities other than the emission of GHGs, for example, road congestion leading to air pollution. Addressing these externalities, e.g., through congestion pricing and energy taxes, could help to lower both air pollution and GHG emissions.

General equilibrium theory

One of the aspects of efficiency for an international agreement

on reducing emissions is participation. In order to be efficient,

mechanisms to reduce emissions still require all emitters to face the

same costs of emission (Goldemberg et al., 1996, p. 30).

Partial participation significantly reduces the effectiveness of

policies to reduce emissions. This is because of how the global economy

is connected through trade.

General equilibrium theory points to a number of difficulties with partial participation (p. 31). Examples are of "leakage" (carbon leakage)

of emissions from countries with regulations on GHG emissions to

countries with less regulation. For example, stringent regulation in

developed countries could result in polluting industries such as aluminium production moving production to developing countries. Leakage is a type of "spillover" effect of mitigation policies.

Estimates of spillover effects are uncertain (Barker et al., 2007).

If mitigation policies are only implemented in Kyoto Annex I countries,

some researchers have concluded that spillover effects might render

these policies ineffective, or possibly even cause global emissions to

increase (Barker et al., 2007). Others have suggested that spillover might be beneficial and result in reduced emission intensities in developing countries.

Comprehensiveness

Efficiency also requires that the costs of emission reductions be minimized (Goldemberg et al., 1996, p. 31). This implies that all GHGs (CO2,

methane, etc.) are considered as part of a policy to reduce emissions,

and also that carbon sinks are included. Perhaps most controversially,

the requirement for efficiency implies that all parts of the Kaya identity are included as part of a mitigation policy. The components of the Kaya identity are:

- CO2 emissions per unit of energy, (carbon intensity)

- energy per unit of output, (energy efficiency)

- economic output per capita,

- and human population.

Efficiency requires that the marginal costs of mitigation for each of

these components is equal. In other words, from the perspective of

improving the overall efficiency of a long-term mitigation strategy,

population control has as much "validity" as efforts made to improve

energy efficiency.

Equity in international agreements

Unlike efficiency, there is no consensus view of how to assess the fairness of a particular climate policy (Bashmakov et al.. 2001:438-439. This does not prevent the study of how a particular policy impacts welfare. Edmonds et al.

(1995) estimated that a policy of stabilizing national emissions

without trading would, by 2020, shift more than 80% of the aggregate

policy costs to non-OECD regions (Bashmakov et al.., 2001:439). A

common global carbon tax would result in an uneven burden of abatement

costs across the world and would change with time. With a global

tradable quota system, welfare impacts would vary according to quota

allocation.

Regional aspects

In a literature assessment, Sathaye et al.. (2001:387-389) described regional barriers to mitigation:

- Developing countries:

- In many developing countries, importing mitigation technologies might lead to an increase in their external debt and balance-of-payments deficit.

- Technology transfer to these countries can be hindered by the possibility of non-enforcement of intellectual property rights. This leaves little incentive for private firms to participate. On the other hand, enforcement of property rights can lead to developing countries facing high costs associated with patents and licensing fees.

- A lack of available capital and finance is common in developing countries.. Together with the absence of regulatory standards, this barrier supports the proliferation of inefficient equipment.

- Economies in transition: In the New Independent States, Sathaye et al. (2007) concluded that a lack of liquidity and a weak environmental policy framework were barriers to investment in mitigation.

Finance

Article 4.2 of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change commits industrialized countries to "[take] the lead" in reducing emissions. The Kyoto Protocol to the UNFCCC has provided only limited financial support to developing countries to assist them in climate change mitigation and adaptation.

Additionally, private sector investment in mitigation and adaptation

could be discouraged in the short and medium term because of the 2008 global financial crisis.

The International Energy Agency

estimates that US$197 billion is required by states in the developing

world above and beyond the underlying investments needed by various

sectors regardless of climate considerations, this is twice the amount

promised by the developed world at the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) Cancún Agreements. Thus, a new method is being developed to help ensure that funding is available for climate change mitigation. This involves financial leveraging, whereby public financing is used to encourage private investment.

The private sector is often unwilling to finance low carbon technologies in developing and emerging economies as the market incentives are often lacking. There are many perceived risks involved, in particular:

- General political risk associated politically instability, uncertain property rights and an unfamiliar legal framework.

- Currency risks are involved is financing is sought internationally and not provided in the nationally currency.

- Regulatory and policy risk - if the public incentives provided by a state may not be actually provided, or if provided, then not for the full length of the investment.

- Execution risk – reflecting concern that the local project developer/firm may lack the capacity and/or experience to execute the project efficiently.

- Technology risk as new technologies involved in low carbon technology may not work as well as expected.

- Unfamiliarity risks occur when investors have never undertaken such projects before.

Funds from the developed world can help mitigate these risks and thus

leverage much larger private funds, the current aim to create $3 of

private investment for every $1 of public funds. Public funds can be used to minimise the risks in the following way.

- Loan guarantees provided by international public financial institutions can be useful to reduce the risk to private lenders.

- Policy insurance can insurance the investor against changes or disruption to government policies designed to encourage low carbon technology, such as a feed-in tariff.

- Foreign exchange liquidity facilities can help reduce the risks associated with borrowing money in a different currency by creating a line of credit that can be drawn on when the project needs money as a result of local currency devaluation but then repaid when the project has a financial surplus.

- Pledge fund can help projects are too small for equity investors to consider or unable to access sufficient equity. In this model, public finance sponsors provide a small amount of equity to anchor and encourage much larger pledges from private investors, such as sovereign wealth funds, large private equity firms and pension funds. Private equity investors will tend to be risk-adverse and focused primarily on long-term profitability, thus all projects would need to meet the fiduciary requirements of the investors.

- Subordinated equity fund - an alternative use of public finance is through the provision of subordinated equity, meaning that the repayment on the equity is of lower priority than the repayment of other equity investors. The subordinated equity would aim to leverage other equity investors by ensuring that the latter have first claim on the distribution of profit, thereby increasing their risk-adjusted returns. The fund would have claim on profits only after rewards to other equity investors were distributed.

Assessing costs and benefits

GDP

The

costs of mitigation and adaptation policies can be measured as a change

in GDP. A problem with this method of assessing costs is that GDP is an

imperfect measure of welfare (Markandya et al.., 2001:478):

- Not all welfare is included in GDP, e.g., housework and leisure activities.

- There are externalities in the economy which mean that some prices might not be truly reflective of their social costs.

Corrections can be made to GDP estimates to allow for these problems,

but they are difficult to calculate. In response to this problem, some

have suggested using other methods to assess policy. For example, the United Nations Commission for Sustainable Development has developed a system for "Green" GDP accounting and a list of sustainable development indicators.

Baselines

The emissions baseline is, by definition, the emissions that would

occur in the absence of policy intervention. Definition of the baseline

scenario is critical in the assessment of mitigation costs (Markandya et al.., 2001:469-470).

This because the baseline determines the potential for emissions

reductions, and the costs of implementing emission reduction policies.

There are several concepts used in the literature over baselines,

including the "efficient" and "business-as-usual" (BAU) baseline cases.

In the efficient baseline, it is assumed that all resources are being

employed efficiently. In the BAU case, it is assumed that future

development trends follow those of the past, and no changes in policies

will take place. The BAU baseline is often associated with high GHG

emissions, and may reflect the continuation of current energy-subsidy

policies, or other market failures.

Some high emission BAU baselines imply relatively low net

mitigation costs per unit of emissions. If the BAU scenario projects a

large growth in emissions, total mitigation costs can be relatively

high. Conversely, in an efficient baseline, mitigation costs per unit of

emissions can be relatively high, but total mitigation costs low.

Ancillary impacts

These

are the secondary or side effects of mitigation policies, and including

them in studies can result in higher or lower mitigation cost estimates

(Markandya et al.., 2001:455).

Reduced mortality and morbidity costs are potentially a major ancillary

benefit of mitigation. This benefit is associated with reduced use of

fossil fuels, thereby resulting in less air pollution (Barker et al.., 2001:564).

There may also be ancillary costs. In developing countries, for

example, if policy changes resulted in a relative increase in

electricity prices, this could result in more pollution (Markandya et al.., 2001:462).

Flexibility

Flexibility

is the ability to reduce emissions at the lowest cost. The greater the

flexibility that governments allow in their regulatory framework to

reduce emissions, the lower the potential costs are for achieving

emissions reductions (Markandya et al.., 2001:455).

- "Where" flexibility allows costs to be reduced by allowing emissions to be cut at locations where it is most efficient to do so. For example, the Flexibility Mechanisms of the Kyoto Protocol allow "where" flexibility (Toth et al., 2001:660).

- "When" flexibility potentially lowers costs by allowing reductions to be made at a time when it is most efficient to do so.

Including carbon sinks in a policy framework is another source of

flexibility. Tree planting and forestry management actions can increase

the capacity of sinks. Soils

and other types of vegetation are also potential sinks. There is,

however, uncertainty over how net emissions are affected by activities

in this area (Markandya et al.., 2001:476).

No regrets options

These are, by definition, emission reduction options that have net negative costs (Markandya et al.., 2001:474-475). The presumption of no regret options affects emission reduction cost estimates (p. 455).

By convention, estimates of emission reduction costs do not

include the benefits of avoided climate change damages. It can be argued

that the existence of no regret options implies that there are market

and non-market failures,

e.g., lack of information, and that these failures can be corrected

without incurring costs larger than the benefits gained. In most cases,

studies of the no regret concept have not included all the external and

implementation costs of a given policy.

Different studies make different assumptions about how far the

economy is from the production frontier (defined as the maximum outputs

attainable with the optimal use of available inputs – natural resources,

labour, etc. (IPCC, 2007c:819)). "Bottom-up" studies (which consider specific technological and engineering

details of the economy) often assume that in the baseline case, the

economy is operating below the production frontier. Where the costs of

implementing policies are less than the benefits, a no regret option

(negative cost) is identified. "Top-down" approaches, based on macroeconomics,

assume that the economy is efficient in the baseline case, with the

result that mitigation policies always have a positive cost.

Technology

Assumptions

about technological development and efficiency in the baseline and

mitigation scenarios have a major impact on mitigation costs, in

particular in bottom-up studies (Markandya et al.., 2001:473). The magnitude of potential technological efficiency improvements depends on assumptions about future technological innovation and market penetration rates for these technologies.

Discount rates

Assessing

climate change impacts and mitigation policies involves a comparison of

economic flows that occur in different points in time. The discount

rate is used by economists to compare economic effects occurring at

different times. Discounting converts future economic impacts into their

present-day value. The discount rate is generally positive because

resources invested today can, on average, be transformed into more

resources later. If climate change mitigation is viewed as an investment, then the return on investment can be used to decide how much should be spent on mitigation.

Integrated assessment models (IAM) are used for to estimate the social cost of carbon. The discount rate is one of the factors used in these models. The IAM frequently used is the Dynamic Integrated Climate-Economy (DICE) model developed by William Nordhaus.

The DICE model uses discount rates, uncertainty, and risks to make

benefit and cost estimations of climate policies and adapt to the

current economic behavior.

The choice of discount rate has a large effect on the result of any climate change cost analysis (Halsnæs et al.., 2007:136).

Using too high a discount rate will result in too little investment in

mitigation, but using too low a rate will result in too much investment

in mitigation. In other words, a high discount rate implies that the

present-value of a dollar is worth more than the future-value of a

dollar.

Discounting can either be prescriptive or descriptive. The

descriptive approach is based on what discount rates are observed in the

behaviour of people making every day decisions (the private discount rate) (IPCC, 2007c:813).

In the prescriptive approach, a discount rate is chosen based on what

is thought to be in the best interests of future generations (the social discount rate).

The descriptive approach can be interpreted as an effort to

maximize the economic resources available to future generations,

allowing them to decide how to use those resources (Arrow et al., 1996b:133-134).

The prescriptive approach can be interpreted as an effort to do as much

as is economically justified to reduce the risk of climate change.

The DICE model incorporates a descriptive approach, in which

discounting reflects actual economic conditions. In a recent DICE

model, DICE-2013R Model, the social cost of carbon is estimated based on

the following alternative scenarios: (1) a baseline scenario, when

climate change policies have not changed since 2010, (2) an optimal

scenario, when climate change policies are optimal (fully implemented

and followed), (3) when the optimal scenario does not exceed 2oC limit

after 1900 data, (4) when the 2oC limit is an average and not the

optimum, (5) when a near-zero (low) discount rate of 0.1% is used (as

assumed in the Stern Review),

(6) when a near-zero discount rate is also used but with calibrated

interest rates, and (7) when a high discount rate of 3.5% is used.

According to Markandya et al.. (2001:466), discount rates used in assessing mitigation programmes need to at least partly reflect the opportunity costs of capital. In developed countries, Markandya et al..

(2001:466) thought that a discount rate of around 4%-6% was probably

justified, while in developing countries, a rate of 10%-12% was cited.

The discount rates used in assessing private projects were found to be

higher – with potential rates of between 10% and 25%.

When deciding how to discount future climate change impacts, value judgements are necessary (Arrow et al.., 1996b:130). IPCC (2001a:9) found that there was no consensus on the use of long-term discount rates in this area.

The prescriptive approach to discounting leads to long-term discount

rates of 2-3% in real terms, while the descriptive approach leads to

rates of at least 4% after tax - sometimes much higher (Halsnæs et al.., 2007:136).

Even today, it is difficult to agree on an appropriate discount

rate. The approach of discounting to be either prescriptive or

descriptive stemmed from the views of Nordhaus and Stern.

Nordhaus takes on a descriptive approach which “assumes that

investments to slow climate change must compete with investments in

other areas.” While Stern takes on a prescriptive approach in which

“leads to the conclusion that any positive pure rate of time preference

is unethical.”

In Nordhaus’ view, his descriptive approach translates that the

impact of climate change is slow, thus investments in climate change

should be on the same level of competition with other investments. He

defines the discount rate to be the rate of return on capital

investments. The DICE model uses the estimated market return on capital

as the discount rate, around an average of 4%. He argues that a higher

discount rate will make future damages look small, thus have less

effort to reduce emissions today. A lower discount rate will make

future damages look larger, thus put more effort to reduce emissions

today.

In Stern’s view, the pure rate of time preference is defined as

the discount rate in a scenario where present and future generations

have equal resources and opportunities.

A zero pure rate of time preference in this case would indicate that

all generations are treated equally. The future generation do not have a

“voice” on today’s current policies, so the present generation are

morally responsible to treat the future generation in the same manner.

He suggests for a lower discount rate in which the present generation

should invest in the future to reduce the risks of climate change.

Assumptions are made to support estimating high and low discount

rates. These estimates depend on future emissions, climate sensitivity

relative to increase in greenhouse gas concentrations, and the

seriousness of impacts over time.

Long-term climate policies will significantly impact future

generations and this is called intergenerational discounting. Factors

that make intergenerational discounting complicated include the great

uncertainty of economic growth, future generations are affected by

today’s policies, and private discounting will be affected due to a

longer “investment horizon.”

Decision analysis

This is a quantitative type of analysis that is used to assess different potential decisions. Examples are cost-benefit and cost-effectiveness analysis (Toth et al.., 2001:609).

In cost-benefit analysis, both costs and benefits are assessed

economically. In cost-effectiveness analysis, the benefit-side of the

analysis, e.g., a specified ceiling for the atmospheric concentration of

GHGs, is not based on economic assessment.

One of the benefits of decision analysis is that the analysis is reproducible. Weaknesses, however, have been citied (Arrow et al.., 1996a:57):

- The decision maker:

- In decision analysis, it is assumed that a single decision maker, with well-order preferences, is present throughout the analysis. In a cost-benefit analysis, the preferences of the decision maker are determined by applying the concepts of "willingness to pay" (WTP) and "willingness to accept" (WTA). These concepts are applied in an attempt to determine the aggregate value that society places on different resources (Markandya et al.., 2001:459).

- In reality, there is no single decision maker. Different decision makers have different sets of values and preferences, and for this reason, decision analysis cannot yield a universally preferred solution.

- Utility valuation: Many of the outcomes of climate policy decisions are difficult to value.

Arrow et al.. (1996a) concluded that while decision analysis

had value, it could not identify a globally optimal policy for

mitigation. In determining nationally optimal mitigation policies, the

problems of decision analysis were viewed as being less important.

Cost-benefit analysis

In an economically efficient mitigation response, the marginal

(or incremental) costs of mitigation would be balanced against the

marginal benefits of emission reduction. "Marginal" means that the costs

and benefits of preventing (abating) the emission of the last unit of

CO2-eq are being compared. Units are measured in tonnes of CO2-eq.

The marginal benefits are the avoided damages from an additional tonne

of carbon (emitted as carbon dioxide) being abated in a given emissions

pathway (the social cost of carbon).

A problem with this approach is that the marginal costs and

benefits of mitigation are uncertain, particularly with regards to the

benefits of mitigation (Munasinghe et al., 1996, p. 159). In the absence of risk aversion,

and certainty over the costs and benefits, the optimum level of

mitigation would be the point where marginal costs equal marginal

benefits. IPCC (2007b:18) concluded that integrated analyses of the

costs and benefits of mitigation did not unambiguously suggest an

emissions pathway where benefits exceed costs

.

Damage function

In cost-benefit analysis, the optimal timing of mitigation

depends more on the shape of the aggregate damage function than the

overall damages of climate change (Fisher et al.., 2007:235).

If a damage function is used that shows smooth and regular damages,

e.g., a cubic function, the results suggest that emission abatement

should be postponed. This is because the benefits of early abatement are

outweighed by the benefits of investing in other areas that accelerate

economic growth. This result can change if the damage function is

changed to include the possibility of catastrophic climate change

impacts.

The mitigation portfolio

In

deciding what role emissions abatement should play in a mitigation

portfolio, different arguments have been made in favour of modest and

stringent near-term abatement (Toth et al.., 2001:658):

- Modest abatement:

- Modest deployment of improving technologies prevents lock-in to existing, low-productivity technology.

- Beginning with modest emission abatement avoids the premature retirement of existing capital stocks.

- Gradual emission reduction reduces induced sectoral unemployment.

- Reduces the costs of emissions abatement.

- There is little evidence of damages from relatively rapid climate change in the past.

- Stringent abatement:

- Endogenous (market-induced) change could accelerate development of low-cost technologies.

- Reduces the risk of being forced to make future rapid emission reductions that would require premature capital retirement.

- Welfare losses might be associated with faster rates of emission reduction. If, in the future, a low GHG stabilization target is found to be necessary, early abatement reduces the need for a rapid reduction in emissions.

- Reduces future climate change damages.

- Cutting emissions more quickly reduces the possibility of higher damages caused by faster rates of future climate change.

Energy sector subsidies

Large energy subsidies are present in many countries (Barker et al., 2001:567-568). Currently governments subsidize fossil fuels by $557 billion per year. Economic theory indicates that the optimal policy would be to remove coal mining

and burning subsidies and replace them with optimal taxes. Global

studies indicate that even without introducing taxes, subsidy and trade

barrier removal at a sectoral level would improve efficiency and reduce

environmental damage (Barker et al., 2001:568). Removal of these subsidies would substantially reduce GHG emissions and stimulate economic growth.

The actual effects of removing fossil fuel subsidies would depend

heavily on the type of subsidy removed and the availability and

economics of other energy sources. There is also the issue of carbon leakage,

where removal of a subsidy to an energy-intensive industry could lead

to a shift in production to another country with less regulation, and

thus to a net increase in global emissions.

Policy suggestions

Jacobson and Delucchi (2009) have advanced a plan to power 100% of the world's energy with wind, hydroelectric, and solar power by the year 2030,

recommending transfer of energy subsidies from fossil fuel to

renewable, and a price on carbon reflecting its cost for flood, cyclone,

hurricane, drought, and related extreme weather expenses.

Cost estimates

Global costs

According to a literature assessment by Barker et al..

(2007:622), mitigation cost estimates depend critically on the baseline

(in this case, a reference scenario that the alternative scenario is

compared with), the way costs are modelled, and assumptions about future

government policy. Fisher et al..

(2007) estimated macroeconomic costs in 2030 for multi-gas mitigation

(reducing emissions of carbon dioxide and other GHGs, such as methane)

as between a 3% decrease in global GDP to a small increase, relative to

baseline. This was for an emissions pathway consistent with atmospheric

stabilization of GHGs between 445 and 710 ppm CO2-eq. In 2050, the estimated costs for stabilization between 710 and 445 ppm CO2-eq

ranged between a 1% gain to a 5.5% decrease in global GDP, relative to

baseline. These cost estimates were supported by a moderate amount of

evidence and much agreement in the literature (IPCC, 2007b:11,18).

Macroeconomic cost estimates made by Fisher et al..

(2007:204) were mostly based on models that assumed transparent markets,

no transaction costs, and perfect implementation of cost-effective

policy measures across all regions throughout the 21st century.

According to Fisher et al.. (2007), relaxation of some or all

these assumptions would lead to an appreciable increase in cost

estimates. On the other hand, IPCC (2007b:8) noted that cost estimates

could be reduced by allowing for accelerated technological learning, or

the possible use of carbon tax/emission permit revenues to reform

national tax systems.

In most of the assessed studies, costs rose for increasingly

stringent stabilization targets. In scenarios that had high baseline

emissions, mitigation costs were generally higher for comparable

stabilization targets. In scenarios with low emissions baselines,

mitigation costs were generally lower for comparable stabilization

targets.

Distributional effects

Regional costs

Gupta et al..

(2007:776-777) assessed studies where estimates are given for regional

mitigation costs. The conclusions of these studies are as follows:

- Regional abatement costs are largely dependent on the assumed stabilization level and baseline scenario. The allocation of emission allowances/permits is also an important factor, but for most countries, is less important than the stabilization level (Gupta et al., 2007, pp. 776–777).

- Other costs arise from changes in international trade. Fossil fuel-exporting regions are likely to be affected by losses in coal and oil exports compared to baseline, while some regions might experience increased bio-energy (energy derived from biomass) exports (Gupta et al., 2007, pp. 776–777).

- Allocation schemes based on current emissions (i.e., where the most allowances/permits are given to the largest current polluters, and the fewest allowances are given to smallest current polluters) lead to welfare losses for developing countries, while allocation schemes based on a per capita convergence of emissions (i.e., where per capita emissions are equalized) lead to welfare gains for developing countries.

Sectoral costs

In a literature assessment, Barker et al. (2001:563-564), predicted that the renewables sector could potentially benefit from mitigation. The coal (and possibly the oil) industry was predicted to potentially lose substantial proportions of output relative to a baseline scenario (Barker et al., 2001, pp. 563–564).