The law of comparative advantage describes how, under free trade, an agent will produce more of and consume less of a good for which they have a comparative advantage.

In an economic model, agents have a comparative advantage over others in producing a particular good if they can produce that good at a lower relative opportunity cost or autarky price, i.e. at a lower relative marginal cost prior to trade. Comparative advantage describes the economic reality of the work gains from trade for individuals, firms, or nations, which arise from differences in their factor endowments or technological progress. (One should not compare the monetary costs of production or even the resource costs (labor needed per unit of output) of production. Instead, one must compare the opportunity costs of producing goods across countries).

David Ricardo developed the classical theory of comparative advantage in 1817 to explain why countries engage in international trade even when one country's workers are more efficient at producing every single good than workers in other countries. He demonstrated that if two countries capable of producing two commodities engage in the free market, then each country will increase its overall consumption by exporting the good for which it has a comparative advantage while importing the other good, provided that there exist differences in labor productivity between both countries. Widely regarded as one of the most powerful yet counter-intuitive insights in economics, Ricardo's theory implies that comparative advantage rather than absolute advantage is responsible for much of international trade.

In an economic model, agents have a comparative advantage over others in producing a particular good if they can produce that good at a lower relative opportunity cost or autarky price, i.e. at a lower relative marginal cost prior to trade. Comparative advantage describes the economic reality of the work gains from trade for individuals, firms, or nations, which arise from differences in their factor endowments or technological progress. (One should not compare the monetary costs of production or even the resource costs (labor needed per unit of output) of production. Instead, one must compare the opportunity costs of producing goods across countries).

David Ricardo developed the classical theory of comparative advantage in 1817 to explain why countries engage in international trade even when one country's workers are more efficient at producing every single good than workers in other countries. He demonstrated that if two countries capable of producing two commodities engage in the free market, then each country will increase its overall consumption by exporting the good for which it has a comparative advantage while importing the other good, provided that there exist differences in labor productivity between both countries. Widely regarded as one of the most powerful yet counter-intuitive insights in economics, Ricardo's theory implies that comparative advantage rather than absolute advantage is responsible for much of international trade.

Classical theory and David Ricardo's formulation

Adam Smith first alluded to the concept of absolute advantage as the basis for international trade in 1776, in The Wealth of Nations:

If a foreign country can supply us with a commodity cheaper than we ourselves can make it, better buy it off them with some part of the produce of our own industry employed in a way in which we have some advantage. The general industry of the country, being always in proportion to the capital which employs it, will not thereby be diminished [...] but only left to find out the way in which it can be employed with the greatest advantage.

Writing several decades after Smith in 1808, Robert Torrens articulated a preliminary definition of comparative advantage as the loss from the closing of trade:

[I]f I wish to know the extent of the advantage, which arises to England, from her giving France a hundred pounds of broadcloth, in exchange for a hundred pounds of lace, I take the quantity of lace which she has acquired by this transaction, and compare it with the quantity which she might, at the same expense of labour and capital, have acquired by manufacturing it at home. The lace that remains, beyond what the labour and capital employed on the cloth, might have fabricated at home, is the amount of the advantage which England derives from the exchange.

David Ricardo

In 1817, David Ricardo published what has since become known as the theory of comparative advantage in his book On the Principles of Political Economy and Taxation.

Ricardo's example

Graph illustrating Ricardo's example:

In case I (diamonds), each country spends 3600 hours to produce a mixture of cloth and wine.

In case II (squares), each country specializes in its comparative advantage, resulting in greater total output.

In case I (diamonds), each country spends 3600 hours to produce a mixture of cloth and wine.

In case II (squares), each country specializes in its comparative advantage, resulting in greater total output.

In a famous example, Ricardo considers a world economy consisting of two countries, Portugal and England, each producing two goods of identical quality. In Portugal, the a priori more efficient country, it is possible to produce wine and cloth

with less labor than it would take to produce the same quantities in

England. However, the relative costs of producing those two goods differ

between the countries.

Produce

Country

|

Cloth | Wine |

|---|---|---|

| England | 100 | 120 |

| Portugal | 90 | 80 |

In this illustration, England could commit 100 hours of labor to produce one unit of cloth, or produce 5/6 units of wine. Meanwhile, in comparison, Portugal could commit 90 hours of labor to produce one unit of cloth, or produce 9/8 units of wine. So, Portugal possesses an absolute advantage in producing cloth due to fewer labor hours, but England has a comparative advantage in producing cloth due to lower opportunity cost.

In the absence of trade, England requires 220 hours of work to

both produce and consume one unit each of cloth and wine while Portugal

requires 170 hours of work to produce and consume the same quantities.

England is more efficient at producing cloth than wine, and Portugal is

more efficient at producing wine than cloth. So, if each country

specializes in the good for which it has a comparative advantage, then

the global production of both goods increases, for England can spend 220

labor hours to produce 2.2 units of cloth while Portugal can spend 170

hours to produce 2.125 units of wine. Moreover, if both countries

specialize in the above manner and England trades a unit of its cloth

for 5/6 to 9/8

units of Portugal's wine, then both countries can consume at least a

unit each of cloth and wine, with 0 to 0.2 units of cloth and 0 to 0.125

units of wine remaining in each respective country to be consumed or

exported. Consequently, both England and Portugal can consume more wine

and cloth under free trade than in autarky.

Ricardian model

The Ricardian model is a general equilibrium mathematical model of international trade. Although the idea of the Ricardian model was first presented in the Essay on Profits (a single-commodity version) and then in the Principles (a multi-commodity version) by David Ricardo, the first mathematical Ricardian model was published by William Whewell in 1833. The earliest test of the Ricardian model was performed by G.D.A MacDougall, which was published in Economic Journal of 1951 and 1952. In the Ricardian model, trade patterns depend on productivity differences.

The following is a typical modern interpretation of the classical Ricardian model. In the interest of simplicity, it uses notation and definitions, such as opportunity cost, unavailable to Ricardo.

The world economy consists of two countries, Home and Foreign,

which produce wine and cloth. Labor, the only factor of production, is mobile

domestically but not internationally; there may be migration between

sectors but not between countries. We denote the labor force in Home by , the amount of labor required to produce one unit of wine in Home by , and the amount of labor required to produce one unit of cloth in Home by . The total amount of wine and cloth produced in Home are and respectively. We denote the same variables for Foreign by appending a prime. For instance, is the amount of labor needed to produce a unit of wine in Foreign.

We don't know if Home is more productive than Foreign in making cloth. That is, we don't know that . Similarly, we don't know if Home has an absolute advantage in wine. However, we will assume that Home is more relatively productive in cloth than Foreign:

Equivalently, we may assume that Home has a comparative advantage in

cloth in the sense that it has a lower opportunity cost for cloth in

terms of wine than Foreign:

In the absence of trade, the relative price of cloth and wine in each

country is determined solely by the relative labor cost of the goods.

Hence the relative autarky price of cloth is in Home and in Foreign. With free trade, the price of cloth or wine in either country is the world price or.

Instead of considering the world demand (or supply) for cloth and wine, we are interested in the world relative demand (or relative supply)

for cloth and wine, which we define as the ratio of the world demand

(or supply) for cloth to the world demand (or supply) for wine. In

general equilibrium, the world relative price will be determined uniquely by the intersection of world relative demand and world relative supply curves.

The demand for cloth relative to wine decreases with the relative price of cloth in terms of wine; the supply of cloth relative to wine increases with relative price. Two relative demand curves and are drawn for illustrative purposes.

We assume that the relative demand curve reflects substitution effects and is decreasing with respect to relative price. The behavior of the relative supply curve, however, warrants closer study. Recalling our original assumption that Home has a comparative advantage in cloth, we consider five possibilities for the relative quantity supplied at a given price.

- If , then Foreign specializes in wine, for the wage in the wine sector is greater than the wage in the cloth sector. However, Home workers are indifferent between working in either sector. As a result, the quantity supplied can take any value.

- If , then both Home and Foreign specialize in wine, for similar reasons as above, and so the quantity supplied is zero.

- If , then Home specializes in cloth whereas Foreign specializes in wine. The quantity supplied is given by the ratio of the world production of cloth to the world production of wine.

- If , then both Home and Foreign specialize in cloth. The quantity supplied tends to infinity as the quantity of wine supplied approaches zero.

- If , then Home specializes in cloth while Foreign workers are indifferent between sectors. Again, the relative quantity supplied can take any value.

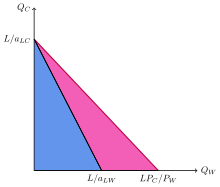

The

blue triangle depicts Home's original production (and consumption)

possibilities. By trading, Home can also consume bundles in the pink

triangle despite facing the same productions possibility frontier.

As long as the relative demand is finite, the relative price is always bounded by the inequality

In autarky, Home faces a production constraint of the form

from which it follows that Home's cloth consumption at the production possibilities frontier is

- .

With free trade, Home produces cloth exclusively, an amount of which

it exports in exchange for wine at the prevailing rate. Thus Home's

overall consumption is now subject to the constraint

while its cloth consumption at the consumption possibilities frontier is given by

- .

A symmetric argument holds for Foreign. Therefore, by trading and

specializing in a good for which it has a comparative advantage, each

country can expand its consumption possibilities. Consumers can choose

from bundles of wine and cloth that they could not have produced

themselves in closed economies.

Terms of trade

Terms

of trade is the rate at which one good could be traded for another. If

both countries specialize in the good for which they have a comparative

advantage then trade, the terms of trade for a good (that benefit both

entities) will fall between each entities opportunity costs. In the

example above one unit of cloth would trade for between units of wine and units of wine.

Haberler's opportunity costs formulation

In

1930 Gottfried Haberler detached the doctrine of comparative advantage

from Ricardo's labor theory of value and provided a modern

opportunity-cost formulation. Haberler's reformulation of comparative

advantage revolutionized the theory of international trade and laid the

conceptual groundwork of modern trade theories.

Haberler's innovation was to reformulate the theory of

comparative advantage such that the value of good X is measured in terms

of the forgone units of production of good Y rather than the labor

units necessary to produce good X, as in the Ricardian formulation.

Haberler implemented this opportunity-cost formulation of comparative

advantage by introducing the concept of a production possibility curve

into international trade theory.

Modern theories

Since 1817, economists have attempted to generalize the Ricardian model and derive the principle of comparative advantage in broader settings, most notably in the neoclassical specific factors Ricardo-Viner (which allows for the model to include more factors than just labour) and factor proportions Heckscher–Ohlin models. Subsequent developments in the new trade theory, motivated in part by the empirical shortcomings of the H–O model and its inability to explain intra-industry trade, have provided an explanation for aspects of trade that are not accounted for by comparative advantage. Nonetheless, economists like Alan Deardorff, Avinash Dixit, Gottfried Haberler, and Victor D. Norman have responded with weaker generalizations of the principle of comparative advantage, in which countries will only tend to export goods for which they have a comparative advantage.

Dornbusch et al.'s continuum of goods formulation

In

both the Ricardian and H–O models, the comparative advantage theory is

formulated for a 2 countries/2 commodities case. It can be extended to a

2 countries/many commodities case, or a many countries/2 commodities

case. Adding commodities in order to have a smooth continuum of goods is

the major insight of the seminal paper by Dornbusch, Fisher, and

Samuelson. In fact, inserting an increasing number of goods into the

chain of comparative advantage makes the gaps between the ratios of the

labor requirements negligible, in which case the three types of

equilibria around any good in the original model collapse to the same

outcome. It notably allows for transportation costs to be incorporated,

although the framework remains restricted to two countries.

But in the case with many countries (more than 3 countries) and many

commodities (more than 3 commodities), the notion of comparative

advantage requires a substantially more complex formulation.

Deardorff's general law of comparative advantage

Skeptics

of comparative advantage have underlined that its theoretical

implications hardly hold when applied to individual commodities or pairs

of commodities in a world of multiple commodities. Deardorff argues

that the insights of comparative advantage remain valid if the theory is

restated in terms of averages across all commodities. His models

provide multiple insights on the correlations between vectors of trade

and vectors with relative-autarky-price measures of comparative

advantage. What has become to be known as the "Deardorff's general law

of comparative advantage" is a model incorporating multiple goods, and

which takes into account tariffs, transportation costs, and other

obstacles to trade.

Alternative approaches

Recently, Y. Shiozawa succeeded in constructing a theory of international value in the tradition of Ricardo's cost-of-production theory of value.

This was based on a wide range of assumptions: Many countries; Many

commodities; Several production techniques for a product in a country;

Input trade (intermediate goods

are freely traded); Durable capital goods with constant efficiency

during a predetermined lifetime; No transportation cost (extendable to

positive cost cases).

In a famous comment McKenzie pointed that "A moment's

consideration will convince one that Lancashire would be unlikely to

produce cotton cloth if the cotton had to be grown in England."

However, McKenzie and later researchers could not produce a general

theory which includes traded input goods because of the mathematical

difficulty.

As John Chipman points it, McKenzie found that "introduction of trade

in intermediate product necessitates a fundamental alteration in

classical analysis."

Durable capital goods such as machines and installations are inputs to

the productions in the same title as part and ingredients.

In view of the new theory, no physical criterion exists.

The competitive patterns are determined by the traders trials to find

cheapest products in a world. The search of cheapest product is achieved

by world optimal procurement. Thus the new theory explains how the

global supply chains are formed.

Empirical approach to comparative advantage

Comparative

advantage is a theory about the benefits that specialization and trade

would bring, rather than a strict prediction about actual behavior. (In

practice, governments restrict international trade for a variety of

reasons; under Ulysses S. Grant,

the US postponed opening up to free trade until its industries were up

to strength, following the example set earlier by Britain.) Nonetheless there is a large amount of empirical

work testing the predictions of comparative advantage. The empirical

works usually involve testing predictions of a particular model. For

example, the Ricardian model predicts that technological differences in

countries result in differences in labor productivity. The differences

in labor productivity in turn determine the comparative advantages

across different countries. Testing the Ricardian model for instance

involves looking at the relationship between relative labor productivity

and international trade patterns. A country that is relatively

efficient in producing shoes tends to export shoes.

Direct test: natural experiment of Japan

Assessing

the validity of comparative advantage on a global scale with the

examples of contemporary economies is analytically challenging because

of the multiple factors driving globalization: indeed, investment,

migration, and technological change play a role in addition to trade.

Even if we could isolate the workings of open trade from other

processes, establishing its causal impact also remains complicated: it

would require a comparison with a counterfactual world without open

trade. Considering the durability of different aspects of globalization,

it is hard to assess the sole impact of open trade on a particular

economy.

Daniel Bernhofen

and John Brown have attempted to address this issue, by using a natural

experiment of a sudden transition to open trade in a market economy.

They focus on the case of Japan.

The Japanese economy indeed developed over several centuries under

autarky and a quasi-isolation from international trade but was, by the

mid-19th century, a sophisticated market economy with a population of 30

million. Under Western military pressure, Japan opened its economy to

foreign trade through a series of unequal treaties.

In 1859, the treaties limited tariffs to 5% and opened trade to

Westerners. Considering that the transition from autarky, or

self-sufficiency, to open trade was brutal, few changes to the

fundamentals of the economy occurred in the first 20 years of trade. The

general law of comparative advantage theorizes that an economy should,

on average, export goods with low self-sufficiency prices and import

goods with high self-sufficiency prices. Bernhofen and Brown found that

by 1869, the price of Japan's main export, silk and derivatives, saw a

100% increase in real terms, while the prices of numerous imported goods

declined of 30-75%. In the next decade, the ratio of imports to gross

domestic product reached 4%.

Structural estimation

Another

important way of demonstrating the validity of comparative advantage

has consisted in 'structural estimation' approaches. These approaches

have built on the Ricardian formulation of two goods for two countries

and subsequent models with many goods or many countries. The aim has

been to reach a formulation accounting for both multiple goods and

multiple countries, in order to reflect real-world conditions more

accurately. Jonathan Eaton and Samuel Kortum underlined that a

convincing model needed to incorporate the idea of a 'continuum of

goods' developed by Dornbusch et al. for both goods and countries. They

were able to do so by allowing for an arbitrary (integer) number i of

countries, and dealing exclusively with unit labor requirements for each

good (one for each point on the unit interval) in each country (of

which there are i).

Earlier empirical work

Two of the first tests of comparative advantage were by MacDougall (1951, 1952).

A prediction of a two-country Ricardian comparative advantage model is

that countries will export goods where output per worker (i.e.

productivity) is higher. That is, we expect a positive relationship

between output per worker and number of exports. MacDougall tested this

relationship with data from the US and UK, and did indeed find a

positive relationship. The statistical test of this positive

relationship was replicated with new data by Stern (1962) and Balassa (1963).

Dosi et al. (1988)

conduct a book-length empirical examination that suggests that

international trade in manufactured goods is largely driven by

differences in national technological competencies.

One critique of the textbook model of comparative advantage is

that there are only two goods. The results of the model are robust to

this assumption. Dornbusch et al. (1977)

generalized the theory to allow for such a large number of goods as to

form a smooth continuum. Based in part on these generalizations of the

model, Davis (1995) provides a more recent view of the Ricardian approach to explain trade between countries with similar resources.

More recently, Golub and Hsieh (2000)

presents modern statistical analysis of the relationship between

relative productivity and trade patterns, which finds reasonably strong

correlations, and Nunn (2007)

finds that countries that have greater enforcement of contracts

specialize in goods that require relationship-specific investments.

Taking a broader perspective, there has been work about the benefits of international trade. Zimring & Etkes (2014) finds that the Blockade of the Gaza Strip,

which substantially restricted the availability of imports to Gaza, saw

labor productivity fall by 20% in three years. Markusen et al. (1994) reports the effects of moving away from autarky to free trade during the Meiji Restoration, with the result that national income increased by up to 65% in 15 years.

Considerations

Development economics

The theory of comparative advantage, and the corollary that nations

should specialize, is criticized on pragmatic grounds within the import substitution industrialization theory of development economics, on empirical grounds by the Singer–Prebisch thesis

which states that terms of trade between primary producers and

manufactured goods deteriorate over time, and on theoretical grounds of infant industry and Keynesian economics. In older economic terms, comparative advantage has been opposed by mercantilism and economic nationalism.

These argue instead that while a country may initially be comparatively

disadvantaged in a given industry (such as Japanese cars in the 1950s),

countries should shelter and invest in industries until they become

globally competitive. Further, they argue that comparative advantage, as

stated, is a static theory – it does not account for the possibility of

advantage changing through investment or economic development, and thus

does not provide guidance for long-term economic development.

Much has been written since Ricardo as commerce has evolved and

cross-border trade has become more complicated. Today trade policy tends

to focus more on "competitive advantage"

as opposed to "comparative advantage". One of the most in-depth

research undertakings on "competitive advantage" was conducted in the

1980s as part of the Reagan administration's Project Socrates

to establish the foundation for a technology-based competitive strategy

development system that could be used for guiding international trade

policy.

Criticism

Several

arguments have been advanced against using comparative advantage as a

justification for advocating free trade, and they have gained an

audience among economists. For example, James Brander and Barbara Spencer

demonstrated how, in a strategic setting where a few firms compete for

the world market, export subsidies and import restrictions can keep

foreign firms from competing with national firms, increasing welfare in

the country implementing these so-called strategic trade policies.

However, the overwhelming consensus of the economics profession

remains that while these arguments against comparative advantage are

theoretically valid under certain conditions or assumptions, these

assumptions do not usually hold. Thus, these arguments should not be

used to guide trade policy. Gregory Mankiw,

chairman of the Harvard Economics Department, has stated: ″Few

propositions command as much consensus among professional economists as

that open world trade increases economic growth and raises living

standards.″

There are some economists who dispute the claims of the benefit of comparative advantage. James K. Galbraith has stated that "free trade has attained the status of a god" and that " ...

none of the world's most successful trading regions, including Japan,

Korea, Taiwan, and now mainland China, reached their current status by

adopting neoliberal trading rules." He argues that " ... comparative advantage is based upon the concept of constant returns:

the idea that you can double or triple the output of any good simply by

doubling or tripling the inputs. But this is not generally the case.

For manufactured products, increasing returns, learning, and technical

change are the rule, not the exception; the cost of production falls

with experience. With increasing returns, the lowest cost will be

incurred by the country that starts earliest and moves fastest on any

particular line. Potential competitors have to protect their own

industries if they wish them to survive long enough to achieve

competitive scale."

According to Galbraith, nations trapped into specializing in

agriculture are condemned to perpetual poverty, as agriculture is

dependent on land, a finite non-increasing natural resource. Galbraith

summarizes: "Comparative advantage has very little practical use for

trade strategy. Diversification, not specialization, is the main path

out of underdevelopment, and effective diversification requires a

strategic approach to trade policy. It cannot mean walling off the

outside world, but it is also a goal not easily pursued under a dogmatic

commitment to free trade."

According to historian Cecil Woodham-Smith,

Ireland in the 1800s is an example of the dangers of

over-specialization. When the union with Great Britain was formed in

1800, Irish textile industries protected by tariffs were exposed to

world markets where England had a comparative advantage in technology,

experience and scale of operation which devastated the Irish industry.

Ireland was forced to specialize in the export of grain while the

displaced Irish labor was forced into subsistence farming and relying on

the potato for survival. When the potato blight occurred the resulting

famine killed at least one million Irish in one of the worst famines in

European history. As Woodham-Smith would later comment, "the Irish

peasant was told to replace the potato by eating his grain, but Trevelyan

once again refused to take any steps to curb the export of food from

Ireland. 'Do not encourage the idea of prohibiting exports,' he wrote,

on September 3, (1846) 'perfect free trade is the right course'."

Free trade is based on the theory of comparative advantage.

The classical and neoclassical formulations of comparative advantage

theory differ in the tools they use but share the same basis and logic.

Comparative advantage theory says that market forces lead all factors of

production to their best use in the economy. It indicates that

international free trade would be beneficial for all participating

countries as well as for the world as a whole because they could

increase their overall production and consume more by specializing

according to their comparative advantages. Goods would become cheaper

and available in larger quantities. Moreover, this specialization would

not be the result of chance or political intent, but would be

automatic. However according to non-neoclassical economists, the theory

is based on assumptions that are neither theoretically nor empirically

valid.

- International mobility of capital and labour

The international immobility of labour and capital is essential to

the theory of comparative advantage. Without this, there would be no

reason for international free trade to be regulated by comparative

advantages. Classical and neoclassical economists all assume that labour

and capital do not circulate between nations. At the international

level, only the goods produced can move freely, with capital and labour

trapped in countries. David Ricardo was aware that the international

immobility of labour and capital is an indispensable hypothesis. He

devoted half of his explanation of the theory to it in his book. He even

explained that if labour and capital could move internationally, then

comparative advantages could not determine international trade. Ricardo

assumed that the reasons for the immobility of the capital would be:

"the fancied or real insecurity of capital, when not under the immediate control of its owner, together with the natural disinclination which every man has to quit the country of his birth and connexions, and intrust himself with all his habits fixed, to a strange government and new laws"

Neoclassical economists, for their part, argue that the scale of

these movements of workers and capital is negligible. They developed the

theory of price compensation by factor that makes these movements

superfluous.

In practice, however, workers move in large numbers from one country to

another. Today, labour migration is truly a global phenomenon. And, with

the reduction in transport and communication costs, capital has become

increasingly mobile and frequently moves from one country to another.

Moreover, the neoclassical assumption that factors are trapped at the

national level has no theoretical basis and the assumption of factor

price equalisation cannot justify international immobility. Moreover,

there is no evidence that factor prices are equal worldwide. Comparative

advantages cannot therefore determine the structure of international

trade.

If they are internationally mobile and the most productive use of

factors is in another country, then free trade will lead them to

migrate to that country. This will benefit the nation to which they

emigrate, but not necessarily the others.

- Externalities

An externality is the term used when the price of a product does not

reflect its cost or real economic value. The classic negative

externality is environmental degradation, which reduces the value of

natural resources without increasing the price of the product that has

caused them harm. The classic positive externality is technological

encroachment, where one company's invention of a product allows others

to copy or build on it, generating wealth that the original company

cannot capture. If prices are wrong due to positive or negative

externalities, free trade will produce sub-optimal results.

For example, goods from a country with lax pollution standards

will be too cheap. As a result, its trading partners will import too

much. And the exporting country will export too much, concentrating its

economy too much in industries that are not as profitable as they seem,

ignoring the damage caused by pollution.

On the positive externalities, if an industry generates

technological spinoffs for the rest of the economy, then free trade can

let that industry be destroyed by foreign competition because the

economy ignores its hidden value. Some industries generate new

technologies, allow improvements in other industries and stimulate

technological advances throughout the economy; losing these industries

means losing all industries that would have resulted in the future.

- Cross-industrial movement of productive resources

Comparative advantage theory deals with the best use of resources and

how to put the economy to its best use. But this implies that the

resources used to manufacture one product can be used to produce another

object. If they cannot, imports will not push the economy into

industries better suited to its comparative advantage and will only

destroy existing industries.

For example, when workers cannot move from one industry to

another—usually because they do not have the right skills or do not live

in the right place—changes in the economy's comparative advantage will

not shift them to a more appropriate industry, but rather to

unemployment or precarious and unproductive jobs.

- Static vs. dynamic gains via international trade

Comparative advantage theory allows for a "static" and not a

"dynamic" analysis of the economy. That is, it examines the facts at a

single point in time and determines the best response to those facts at

that point in time, given our productivity in various industries. But

when it comes to long-term growth, it says nothing about how the facts

can change tomorrow and how they can be changed in someone's favour. It

does not indicate how best to transform factors of production into more

productive factors in the future.

According to theory, the only advantage of international trade is

that goods become cheaper and available in larger quantities. Improving

the static efficiency of existing resources would therefore be the only

advantage of international trade. And the neoclassical formulation

assumes that the factors of production are given only exogenously.

Exogenous changes can come from population growth, industrial policies,

the rate of capital accumulation (propensity for security) and

technological inventions, among others. Dynamic developments endogenous

to trade such as economic growth are not integrated into Ricardo's

theory. And this is not affected by what is called "dynamic comparative

advantage". In these models, comparative advantages develop and change

over time, but this change is not the result of trade itself, but of a

change in exogenous factors.

However, the world, and in particular the industrialized

countries, are characterized by dynamic gains endogenous to trade, such

as technological growth that has led to an increase in the standard of

living and wealth of the industrialized world. In addition, dynamic

gains are more important than static gains.

- Balanced trade and adjustment mechanisms

A crucial assumption in both the classical and neoclassical

formulation of comparative advantage theory is that trade is balanced,

which means that the value of imports is equal to the value of each

country's exports. The volume of trade may change, but international

trade will always be balanced at least after a certain adjustment

period. The balance of trade is essential for theory because the

resulting adjustment mechanism is responsible for transforming the

comparative advantages of production costs into absolute price

advantages. And this is necessary because it is the absolute price

differences that determine the international flow of goods. Since

consumers buy a good from the one who sells it cheapest, comparative

advantages in terms of production costs must be transformed into

absolute price advantages. In the case of floating exchange rates, it is

the exchange rate adjustment mechanism that is responsible for this

transformation of comparative advantages into absolute price advantages.

In the case of fixed exchange rates, neoclassical theory suggests that

trade is balanced by changes in wage rates.

So if trade were not balanced in itself and if there were no

adjustment mechanism, there would be no reason to achieve a comparative

advantage. However, trade imbalances are the norm and balanced trade is

in practice only an exception. In addition, financial crises such as the

Asian crisis of the 1990s show that balance of payments imbalances are

rarely benign and do not self-regulate. There is no adjustment mechanism

in practice. Comparative advantages do not turn into price differences

and therefore cannot explain international trade flows.

Thus, theory can very easily recommend a trade policy that gives

us the highest possible standard of living in the short term but none in

the long term. This is what happens when a nation runs a trade deficit,

which necessarily means that it goes into debt with foreigners or sells

its existing assets to them. Thus, the nation applies a frenzy of

consumption in the short term followed by a long-term decline.

- International trade as bartering

The assumption that trade will always be balanced is a corollary of

the fact that trade is understood as barter. The definition of

international trade as barter trade is the basis for the assumption of

balanced trade. Ricardo insists that international trade takes place as

if it were purely a barter trade, a presumption that is maintained by

subsequent classical and neoclassical economists. The quantity of money

theory, which Ricardo uses, assumes that money is neutral and neglects

the velocity of a currency. Money has only one function in

international trade, namely as a means of exchange to facilitate trade.

In practice, however, the velocity of circulation is not

constant and the quantity of money is not neutral for the real economy. A

capitalist world is not characterized by a barter economy but by a

market economy. The main difference in the context of international

trade is that sales and purchases no longer necessarily have to

coincide. The seller is not necessarily obliged to buy immediately.

Thus, money is not only a means of exchange. It is above all a means of

payment and is also used to store value, settle debts and transfer

wealth. Thus, unlike the barter hypothesis of the comparative advantage

theory, money is not a commodity like any other. Rather, it is of

practical importance to specifically own money rather than any

commodity. And money as a store of value in a world of uncertainty has a

significant influence on the motives and decisions of wealth holders

and producers.

- Using labour and capital to their full potential

Ricardo and later classical economists assume that labour tends

towards full employment and that capital is always fully used in a

liberalized economy, because no capital owner will leave its capital

unused but will always seek to make a profit from it. That there is no

limit to the use of capital is a consequence of Jean-Baptiste Say's law,

which presumes that production is limited only by resources and is also

adopted by neoclassical economists.

From a theoretical point of view, comparative advantage theory

must assume that labour or capital is used to its full potential and

that resources limit production. There are two reasons for this: the

realization of gains through international trade and the adjustment

mechanism. In addition, this assumption is necessary for the concept of

opportunity costs. If unemployment (or underutilized resources) exists,

there are no opportunity costs, because the production of one good can

be increased without reducing the production of another good. Since

comparative advantages are determined by opportunity costs in the

neoclassical formulation, these cannot be calculated and this

formulation would lose its logical basis.

If a country's resources were not fully utilized, production and

consumption could be increased at the national level without

participating in international trade. The whole raison d'être of

international trade would disappear, as would the possible gains. In

this case, a State could even earn more by refraining from participating

in international trade and stimulating domestic production, as this

would allow it to employ more labour and capital and increase national

income. Moreover, any adjustment mechanism underlying the theory no

longer works if unemployment exists.

In practice, however, the world is characterised by unemployment.

Unemployment and underemployment of capital and labour are not a

short-term phenomenon, but it is common and widespread. Unemployment and

untapped resources are more the rule than the exception.