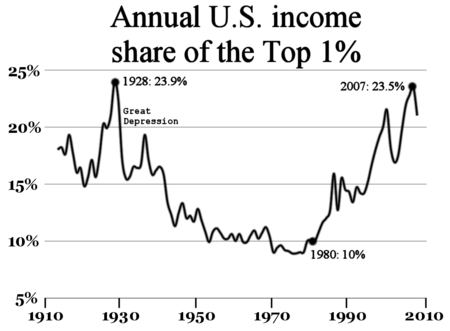

U.S. inequality from 1913–2008.

Income inequality in the United States grew significantly beginning in the early 1970s, after several decades of stability.

The US consistently exhibits higher rates of income inequality than

most developed nations, arguably due to the nation's relatively less

regulated markets.

According to the Congressional Budget Office,

"the precise reasons for the [recent] rapid growth in income at the top

are not well understood", but "in all likelihood," an "interaction of

multiple factors" was involved. Researchers have offered several potential rationales. Various rationales conflict or overlap. They include:

- globalization – Lesser-skilled American workers have been losing ground in the face of competition from workers in Asia and other emerging economies.

- skills – The rapid pace of progress in information technology has increased the relative demand for higher-skilled workers.

- superstars – Compensation in many sectors turned into a tournament in which the winner is richly rewarded, while the runners-up get far less. This affects both workers and investors (in dominant firms).

- immigration – Relatively high levels of immigration of less-skilled workers since 1965 may have reduced wages for American-born high school dropouts.

- decline of unions – Unions helped increase wages, benefits and working conditions. Unionized workers declined from over 30% to around 12%.

- social norms – Social norms constrained executive pay. CEO pay rose from around 40 times the average workers pay in the 1970s to over 350 times in the early 2000s.

Divergence of productivity and compensation

Illustrates

the productivity gap (i.e., the annual growth rate in productivity

minus annual growth rate in compensation) by industry from 1985–2015.

Each dot is an industry; dots above the line have a productivity gap

(i.e., productivity growth has exceeded compensation growth), those

below the line do not.

Overall

One

view of economic equity is that employee compensation should rise with

productivity (defined as real output per hour of labor worked). In

other words, if the employee produces more, they should be paid

accordingly. If pay lags behind productivity, income inequality grows,

as labor's share of the output is falling, while capital's share

(generally higher-income owners) is rising.

According to a June 2017 report from the non-partisan Bureau of Labor Statistics

(BLS), productivity rose in tandem with employee compensation (a

measure which includes wages as well as benefits such as health

insurance) from the 1940s through the 1970s. However, since then

productivity has grown faster than compensation. BLS refers to this as

the "productivity-compensation gap", an issue which has garnered much

attention from academics and policymakers.

BLS reported this gap occurs across most industries: "When examined at a

detailed industry level, the average annual percent change in

productivity outpaced compensation in 83 percent of 183 industries

studied" measured from 1987–2015.

For example, in the information industry, productivity increased at an

annual average rate of 5.0% over the 1987-2015 period, while

compensation increased at about a 1.5% rate, resulting in a 3.5%

productivity gap. In Manufacturing, the gap was 2.7%; in Retail Trade

2.6%; and in Transportation and Warehousing 1.3%. This analysis adjusted

for inflation using the Consumer Price Index or CPI, a measure of inflation based on what is consumed, rather than what is produced.

Analyzing the gap

BLS

explained the gap between productivity and compensation can be divided

into two components, the effect of which varies by industry: 1)

Recalculating the gap using an industry-specific inflation adjustment

("industry deflator") rather than consumption (CPI); and 2) The change

in labor's share of income, defined as how much of a business' revenue

goes to workers as opposed to intermediate purchases (i.e., cost of

goods) and capital (owners) in that industry.

The difference in deflators was the stronger effect among high

productivity growth industries, while the change in labor's share of

income was the stronger effect among most other industries. For example,

the 3.5% productivity gap in the information industry was composed of a

2.1% difference in deflators and about a 1.4% due to change in labor

share. The 2.7% gap in Manufacturing included 1.0% due to deflator and

1.7% due to change in labor share.

Reasons for the gap

BLS explained the decline in labor share as likely driven by three factors that vary by industry:

- Globalization: Income that might have gone to domestic workers is going to foreign workers due to offshoring (i.e., production and service activities in other countries).

- Increased automation: More automation means more share of income attributed to capital.

- Faster capital depreciation: Information assets depreciate more rapidly than machinery; the latter were the greater share of the capital base in the past. This may require a higher capital share to generate income than in the past.

Market factors

Globalization

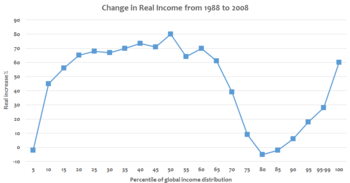

Change in real income between 1988 and 2008 at various income percentiles of global income distribution.

The

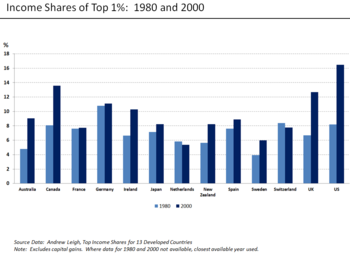

bar chart compares pre-tax income shares of the top 1% in 13 developed

countries for 1980 and 2000. The degree of change varied significantly,

indicating country-specific policy factors also impact inequality.

Globalization refers to the integration of economies in terms of trade, information, and jobs. Innovations in supply chain management

enabled goods to be sourced in Asia and shipped to the United States

less expensively than in the past. This integration of economies,

particularly with the U.S. and Asia, had dramatic impacts on income

inequality globally.

Economist Branko Milanovic

analyzed global income inequality, comparing 1988 and 2008. His

analysis indicated that the global top 1% and the middle classes of the

emerging economies (e.g., China, India, Indonesia, Brazil and Egypt)

were the main winners of globalization during that time. The real

(inflation adjusted) income of the global top 1% increased approximately

60%, while the middle classes of the emerging economies (those around

the 50th percentile of the global income distribution in 1988) rose

70–80%. For example, in 2000, 5 million Chinese households earned

between $11,500 and $43,000 in 2016 dollars. By 2015, 225 million did.

On the other hand, those in the middle class of the developed world

(those in the 75th to 90th percentile in 1988, such as the American

middle class) experienced little real income gains. The richest 1%

contains 60 million persons globally, including 30 million Americans

(i.e., the top 12% of Americans by income were in the global top 1% in

2008), the most out of any country.

While economists who have studied globalization agree imports

have had an effect, the timing of import growth does not match the

growth of income inequality. By 1995 imports of manufactured goods from

low-wage countries totalled less than 3% of US gross domestic product. It wasn't until 2006 that the US imported more manufactured goods

from low-wage (developing) countries than from high-wage (advanced)

economies.

Inequality increased during the 2000–2010 decade not because of

stagnating wages for less-skilled workers, but because of accelerating

incomes of the top 0.1%.

Author Timothy Noah estimates that "trade", increases in imports are

responsible for just 10% of the "Great Divergence" in income

distribution.

Journalist James Surowiecki

notes that in the last 50 years, companies and the sectors of the

economy providing the most employment in the US – major retailers,

restaurant chains, and supermarkets – are ones with lower profit margins

and less pricing power than in the 1960s; while sectors with high

profit margins and average salaries – like high technology – have

relatively few employees.

Some economists claim that it is WTO-led

globalization and competition from developing countries, especially

China, that has resulted in the recent decline in labor's share of

income and increased unemployment in the U.S. And the Economic Policy Institute and the Center for Economic and Policy Research argue that some trade agreements such as the Trans-Pacific Partnership could result in further job losses and declining wages.

One argument contrary to the globalization/technology hypothesis

relates to variation across countries. Japan, Sweden and France did not

experience significant increases in income inequality during the

1979–2010 period, although the U.S. did. The top 1% income group

continued to receive less than 10% of the income share in these

countries, while the U.S. share rose from 10% to over 20%. Economist Emmanuel Saez

wrote in 2014: "Differences across countries rule out technical

change/globalization as the sole explanation ... Policies play a key

role in shaping inequality (tax and transfer policies, regulations,

education)."

Superstar hypothesis

Eric Posner and Glen Weyl

point out that inequality can be predominantly explained by the

superstar hypothesis. In their opinion Piketty fails to observe the

accelerated turnover that is occurring in the Forbes 400; only 35 people

from the original 1982 list remain today. Many have fallen off as a

result of heavy spending, large-scale philanthropy, and bad investments.

The current Forbes 400 is now primarily made up of newly wealthy

business owners, not heirs and heiresses. In parallel research, the University of Chicago's Steven Kaplan and Stanford University's

Joshua Rauh note that 69% of those on the Forbes list are actually

first generation wealth creators. That figure has risen dramatically

since 1982 when it stood at 40%.

Ed Dolan supports the globalization and superstar hypothesis but points out that the high earnings are based, to some extent, on moral hazard like "Bonus-based compensation schemes with inadequate clawback for losses" and the shift of losses to shareholders, unsecured creditors, or taxpayers.

Paul Krugman argues that for the US the surge in inequality to date is

mainly due to supersalaries but capital has nonetheless been significant

too. And when the current generation of the 1% turn over their wealth

to their heirs these become rentiers, people who live off accumulated

capital. Two decades from now America could turn into a

rentier-dominated society even more unequal than Belle Époque Europe.

One study extended the superstar hypothesis to corporations, with

firms that are more dominant in their industry (in some cases due to

oligopoly or monopoly) paying their workers far more than the average in

the industry. Another study noted that "superstar firms" is another

explanation for the decline in the overall share of income (GDP) going

to workers/labor as opposed to owners/capital.

Education

Median personal and household income according to different education levels.

Income differences between the varying levels of educational

attainment (usually measured by the highest degree of education an

individual has completed) have increased. Expertise and skill certified

through an academic degree translates into increased scarcity of an

individual's occupational qualification which in turn leads to greater

economic rewards. As the United States has developed into a post-industrial society

more and more employers require expertise that they did not a

generation ago, while the manufacturing sector which employed many of

those lacking a post-secondary education is decreasing in size.

In the resulting economic job market the income discrepancy between the working class and the professional with the higher academic degrees, who possess scarce amounts of certified expertise, may be growing.

Households in the upper quintiles are generally home to more,

better educated and employed working income earners, than those in lower

quintiles.

Among those in the upper quintile, 62% of householders were college

graduates, 80% worked full-time and 76% of households had two or more

income earners, compared to the national percentages of 27%, 58% and

42%, respectively.

Upper-most sphere

US Census Bureau data indicated that occupational achievement and the

possession of scarce skills correlates with higher income.

Average earnings in 2002 for the population 18 years and over were higher at each progressively higher level of education ... This relationship holds true not only for the entire population but also across most subgroups. Within each specific educational level, earnings differed by sex and race. This variation may result from a variety of factors, such as occupation, working full- or part-time, age, or labor force experience.

The "college premium" refers to the increase in income to workers

with four-year college degrees relative to those without. The college

premium doubled from 1980 to 2005, as the demand for college-educated

workers has exceeded the supply. Economists Goldin and Katz estimate

that the increase in economic returns to education was responsible for

about 60% of the increase in wage inequality between 1973 and 2005. The

supply of available graduates did not keep up with business demand due

primarily to increasingly expensive college educations. Annual tuition

at public and private universities averaged 4% and 20% respectively of

the annual median family income from the 1950s to 1970s; by 2005 these

figures were 10% and 45% as colleges raised prices in response to

demand.

Economist David Autor wrote in 2014 that approximately two-thirds of

the rise in income inequality between 1980 and 2005 was accounted for by

the increased premium associated with education in general and

post-secondary education in particular.

Two researchers have suggested that children in low income

families are exposed to 636 words an hour, as opposed to 2,153 words in

high income families during the first four formative years of a child's

development. This, in turn, led to low achievement in later schooling

due to the inability of the low income group to verbalize concepts.

A psychologist has stated that society stigmatizes poverty.

Conversely, poor people tend to believe that the wealthy have been lucky

or have earned their money through illegal means. She believes that

both attitudes need to be discarded if the nation is to make headway in

addressing the issue of inequality. She suggests that college not be a

litmus test of success; that valorizing of one profession as more

important than another is a problem.

Skill-biased technological change

U.S. real wages remain below their 1970's peak.

As of the mid- to late- decade of the 2000s, the most common

explanation for income inequality in America was "skill-biased

technological change" (SBTC) – "a shift in the production technology that favors skilled over unskilled labor by increasing its relative productivity and, therefore, its relative demand".

For example, one scholarly colloquium on the subject that included many

prominent labor economists estimated that technological change was

responsible for over 40% of the increase in inequality. Other factors

like international trade, decline in real minimum wage, decline in

unionization and rising immigration, were each responsible for 10–15% of

the increase.

Education has a notable influence on income distribution.

In 2005, roughly 55% of income earners with doctorate degrees – the

most educated 1.4% – were among the top 15 percent earners. Among those

with master's degrees – the most educated 10% – roughly half had incomes

among the top 20 percent of earners. Only among households in the top quintile were householders with college degrees in the majority.

But while the higher education commonly translates into higher income, and the highly educated are disproportionately represented in upper quintile households,

differences in educational attainment fail to explain income

discrepancies between the top 1 percent and the rest of the population.

Large percentages of individuals lacking a college degree are present in all income demographics, including 33% of those with heading households with six figure incomes.

From 2000 to 2010, the 1.5% of Americans with an M.D., J.D., or M.B.A.

and the 1.5% with a PhD saw median income gains of approximately 5%.

Among those with a college or master's degree (about 25% of the American

workforce) average wages dropped by about 7%, (though this was less

than the decline in wages for those who had not completed college).

Post-2000 data has provided "little evidence" for SBTC's role in

increasing inequality. The wage premium for college educated has risen

little and there has been little shift in shares of employment to more

highly skilled occupations.

Approaching the issue from occupations that have been replaced or

downgraded since the late 1970s, one scholar found that jobs that

"require some thinking but not a lot" – or moderately skilled

middle-class occupations such as cashiers, typists, welders, farmers,

appliance repairmen – declined the furthest in wage rates and/or

numbers. Employment requiring either more skill or less has been less

affected.

However the timing of the great technological change of the era –

internet use by business starting in the late 1990s – does not match

that of the growth of income inequality (starting in the early 1970s but

slackening somewhat in the 1990s). Nor does the introduction of

technologies that increase the demand for more skilled workers seem to

be generally associated with a divergence in household income among the

population. Inventions of the 20th century such as AC electric power,

the automobile, airplane, radio, television, the washing machine, Xerox

machine, each had an economic impact similar to computers,

microprocessors and internet, but did not coincide with greater

inequality.

Another explanation is that the combination of the introduction of technologies that increase the demand for skilled workers, and

the failure of the American education system to provide a sufficient

increase in those skilled workers has bid up those workers' salaries. An

example of the slowdown in education growth in America (that began

about the same time as the Great Divergence began) is the fact that the

average person born in 1945 received two more years of schooling than

his parents, while the average person born in 1975 received only half a

year more of schooling.

Author Timothy Noah's "back-of-the-envelope" estimation based on

"composite of my discussions with and reading of the various economists

and political scientists" is that the "various failures" in America's

education system are "responsible for 30%" of the post-1978 increase in

inequality.

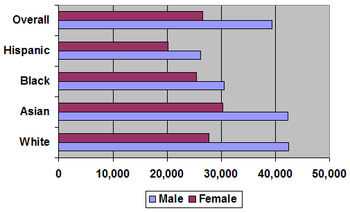

Race and gender disparities

Median personal income by gender and race in 2005.

Income levels vary by gender and race with median income levels

considerably below the national median for females compared to men with

certain racial demographics.

Despite considerable progress in pursuing gender and racial

equality, some social scientists like Richard Schaeffer attribute these

discrepancies in income partly to continued discrimination.

Among women, part of the wage gap is due to employment choices

and preferences. Women are more likely to consider factors other than

salary when looking for employment. On average, women are less willing

to travel or relocate, take more hours off and work fewer hours, and

choose college majors that lead to lower paying jobs. Women are also

more likely to work for governments or non-profits which pay less than

the private sector.

According to this perspective certain ethnic minorities and women

receive fewer promotions and opportunities for occupation and economic

advancement than others. In the case of women this concept is referred

to as the glass ceiling keeping women from climbing the occupational ladder.

In terms of race, Asian Americans are far more likely to be in the highest earning 5 percent than the rest of Americans. Studies have shown that African Americans are less likely to be hired than White Americans with the same qualifications.

The continued prevalence of traditional gender roles and ethnic

stereotypes may partially account for current levels of discrimination.

In 2005, median income levels were highest among Asian and White males

and lowest among females of all races, especially those identifying as

African American or Hispanic. Despite closing gender and racial gaps,

considerable discrepancies remain among racial and gender demographics,

even at the same level of educational attainment.

The economic success of Asian Americans may come from how they devote

much more time to education than their peers. Asian Americans have

significantly higher college graduation rates than their peers and are

much more likely to enter high status and high income occupations.

Median weekly earnings of full-time wage and salary workers, by sex, race, and ethnicity, 2009.

Since 1953 the income gap between male and female workers has decreased considerably but remains relatively large. Women currently earn significantly more Associate's, Bachelor's, and master's degrees than men and almost as many Doctorates.

Women are projected to have passed men in Doctorates earned in

2006–2007, and to earn nearly two thirds of Associate's, Bachelor's, and

master's degrees by 2016.

Though it is important to note that income inequality between sexes remained stark at all levels of educational attainment.

Between 1953 and 2005 median earnings as well as educational attainment

increased, at a far greater pace for women than for men. Median income

for female earners male earners increased 157.2% versus 36.2% for men,

over four times as fast. Today the median male worker earns roughly

68.4% more than their female counterparts, compared to 176.3% in 1953.

The median income of men in 2005 was 2% higher than in 1973 compared to a

74.6% increase for female earners.

Racial differences remained stark as well, with the highest

earning sex-gender demographic of workers aged 25 or older, Asian males

(who were roughly tied with white males) earning slightly more than twice as much as the lowest-earning demographic, Hispanic females. As mentioned above, inequality between races and gender persisted at similar education levels.

Racial differences were overall more pronounced among male than among

female income earners. In 2009, Hispanics were more than twice as likely

to be poor than non-Hispanic whites, research indicates.

Lower average English ability, low levels of educational attainment,

part-time employment, the youthfulness of Hispanic household heads, and

the 2007–09 recession are important factors that have pushed up the

Hispanic poverty rate relative to non-Hispanic whites. During the early

1920s, median earnings decreased for both sexes, not increasing

substantially until the late 1990s. Since 1974 the median income for

workers of both sexes increased by 31.7% from $18,474 to $24,325,

reaching its high-point in 2000.

Incentives

Percent of households with 2+ income earners, and full-time workers by income.

In the context of concern over income inequality, a number of economists, such as Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke, have talked about the importance of incentives: "... without

the possibility of unequal outcomes tied to differences in effort and

skill, the economic incentive for productive behavior would be

eliminated, and our market-based economy ... would function far less

effectively."

Since abundant supply decreases market value, the possession of scarce skills considerably increases income.

Among the American lower class, the most common source of income was not occupation, but government welfare.

Stock buybacks

Writing in the Harvard Business Review

in September 2014, William Lazonick blamed record corporate stock

buybacks for reduced investment in the economy and a corresponding

impact on prosperity and income inequality. Between 2003 and 2012, the

449 companies in the S&P 500 used 54% of their earnings ($2.4

trillion) to buy back their own stock. An additional 37% was paid to

stockholders as dividends. Together, these were 91% of profits. This

left little for investment in productive capabilities or higher income

for employees, shifting more income to capital rather than labor. He

blamed executive compensation arrangements, which are heavily based on

stock options, stock awards and bonuses for meeting earnings per share

(EPS) targets (EPS increases as the number of outstanding shares

decreases). Restrictions on buybacks were greatly eased in the early

1980s. He advocates changing these incentives to limit buybacks.

U.S. companies are projected to increase buybacks to $701 billion

in 2015 according to Goldman Sachs, an 18% increase over 2014. For

scale, annual non-residential fixed investment (a proxy for business

investment and a major GDP component) was estimated to be about $2.1

trillion for 2014.

Journalist Timothy Noah

wrote in 2012 that: "My own preferred hypothesis is that stockholders

appropriated what once belonged to middle-class wage earners." Since the

vast majority of stocks are owned by higher income households, this

contributes to income inequality. Journalist Harold Meyerson

wrote in 2014 that: "The purpose of the modern U.S. corporation is to

reward large investors and top executives with income that once was

spent on expansion, research, training and employees."

Tax and transfer policies

Background

Distribution of US federal taxes from 1979 to 2013, based on CBO Estimates.

U.S. income inequality is comparable to other developed nations

pre-tax, but is among the worst after-tax and transfers. This indicates

the U.S. tax policies redistribute income from higher income to lower

income households relatively less than other developed countries. Journalist Timothy Noah summarized the results of several studies his 2012 book The Great Divergence:

- Economists Piketty and Saez reported in 2007, that U.S. taxes on the rich had declined over the 1979–2004 period, contributing to increasing after-tax income inequality. While dramatic reductions in the top marginal income tax rate contributed somewhat to worsening inequality, other changes to the tax code (e.g., corporate, capital gains, estate, and gift taxes) had more significant impact. Considering all federal taxes, including the payroll tax, the effective tax rate on the top 0.01% fell dramatically, from 59.3% in 1979 to 34.7% in 2004. CBO reported an effective tax rate decline from 42.9% in 1979 to 32.3% in 2004 for the top 0.01%, using a different income measurement. In other words, the effective tax rate on the very highest income taxpayers fell by about one-quarter.

- CBO estimated that the combined effect of federal taxes and government transfers reduced income inequality (as measured by the Gini Index) by 23% in 1979. By 2007, the combined effect was to reduce income inequality by 17%. So the tax code remained progressive, only less so.

- While pre-tax income is the primary driver of income inequality, the less progressive tax code further increased the share of after-tax income going to the highest income groups. For example, had these tax changes not occurred, the after-tax income share of the top 0.1% would have been approximately 4.5% in 2000 instead of the 7.3% actual figure.[47]

Income taxes

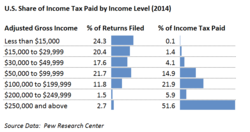

Share

of income tax paid by level of income. The top 2.7% of taxpayers (those

with income over $250,000) paid 51.6% of the federal income taxes in

2014.

A key factor in income inequality/equality is the effective rate at which income is taxed coupled with the progressivity of the tax system. A progressive tax is a tax in which the effective tax rate increases as the taxable base amount increases. Overall income tax rates in the U.S. are below the OECD average, and until 2005 have been declining.

How much tax policy change over the last thirty years has

contributed to income inequality is disputed. In their comprehensive

2011 study of income inequality (Trends in the Distribution of Household Income Between 1979 and 2007), the CBO found that,

The top fifth of the population saw a 10-percentage-point increase in their share of after-tax income. Most of that growth went to the top 1 percent of the population. All other groups saw their shares decline by 2 to 3 percentage points. In 2007, federal taxes and transfers reduced the dispersion of income by 20 percent, but that equalizing effect was larger in 1979. The share of transfer payments to the lowest-income households declined. The overall average federal tax rate fell.

However, a more recent CBO analysis indicates that with changes to 2013 tax law (e.g., the expiration of the 2001-2003 Bush tax cuts for top earners and the increased payroll taxes passed as part of the Affordable Care Act), the effective federal tax rates for the highest earning household will increase to levels not seen since 1979.

According to journalist Timothy Noah, "you can't really

demonstrate that U.S. tax policy had a large impact on the three-decade

income inequality trend one way or the other. The inequality trend for

pre-tax income during this period was much more dramatic." Noah estimates tax changes account for 5% of the Great Divergence.

But many – such as economist Paul Krugman – emphasize the effect of changes in taxation – such as the 2001 and 2003 Bush administration tax cuts which cut taxes far more for high-income households than those below – on increased income inequality.

Part of the growth of income inequality under Republican

administrations (described by Larry Bartels) has been attributed to tax

policy. A study by Thomas Piketty and Emmanuel Saez found that "large

reductions in tax progressivity

since the 1960s took place primarily during two periods: the Reagan

presidency in the 1980s and the Bush administration in the early 2000s."

During Republican President Ronald Reagan's

tenure in office the top marginal income tax rate was reduced from over

70 to 28 percent, high top marginal rates like 70% being the sort in

place during much of the period of great income equality following the

"Great Compression". The lowest marginal rate for the bottom fell from 14 to 11 percent.

However the effective rate on top earners before Reagan's tax cut was

much lower because of loopholes and charitable contributions.

Robert Bellafiore and Madison Mauro, writing for the Tax Foundation, calculated that effective tax rates for the richest Americans has declined since 1986. But the share of income taxes paid by the richest Americans has increased, due to tax expenditures increasing the number of low-income Americans with negative tax rates.

Taxes on capital

Selected economic variables related to wealth and income equality, comparing 1979, 2007, and 2015.

Taxes on income derived from capital (e.g., financial assets,

property and businesses) primarily affect higher income groups, who own

the vast majority of capital. For example, in 2010 approximately 81% of

stocks were owned by the top 10% income group and 69% by the top 5%.

Only about one-third of American households have stock holdings more

than $7,000. Therefore, since higher-income taxpayers have a much higher

share of their income represented by capital gains, lowering taxes on

capital income and gains increases after-tax income inequality.

Capital gains taxes were reduced around the time income

inequality began to rise again around 1980 and several times thereafter.

During 1978 under President Carter, the top capital gains tax rate was

reduced from 49% to 28%. President Ronald Reagan's 1981 cut in the top

rate on unearned income reduced the maximum capital gains rate to only

20% – its lowest level since the Hoover administration, as part of an

overall economic growth strategy. The capital gains tax rate was also

reduced by President Bill Clinton in 1997, from 28% to 20%. President

George W. Bush reduced the tax rate on capital gains and qualifying

dividends from 20% to 15%, less than half the 35% top rate on ordinary

income.

CBO reported in August 1990 that: "Of the 8 studies reviewed,

five, including the two CBO studies, found that cutting taxes on capital

gains is not likely to increase savings, investment, or GNP much if at

all." Some of the studies indicated the loss in revenue from lowering

the tax rate may be offset by higher economic growth, others did not.

Journalist Timothy Noah

wrote in 2012 that: "Every one of these changes elevated the financial

interests of business owners and stockholders above the well-being,

financial or otherwise, or ordinary citizens." So overall, while cutting capital gains taxes adversely affects income inequality, its economic benefits are debatable.

Other tax policies

Rising

inequality has also been attributed to President Bush's veto of tax

harmonization, as this would have prohibited offshore tax havens.

Debate over effects of tax policies

One study

found reductions of total effective tax rates were most significant for

individuals with highest incomes. (see "Federal Tax Rate by Income

Group" chart) For those with incomes in the top 0.01 percent, overall

rates of Federal tax fell from 74.6% in 1970, to 34.7% in 2004 (the

reversal of the trend in 2000 with a rise to 40.8% came after the 1993 Clinton deficit reduction tax bill),

the next 0.09 percent falling from 59.1% to 34.1%, before leveling off

with a relatively modest drop of 41.4 to 33.0% for the 99.5–99.9 percent

group. Although the tax rate for low-income earners fell as well

(though not as much), these tax reductions compare with virtually no

change – 23.3% tax rate in 1970, 23.4% in 2004 – for the US population

overall.

We haven't achieved

the minimalist state that libertarians advocate. What we've achieved is a

state too constrained to provide the public goods—investments in

infrastructure, technology, and education—that would make for a vibrant

economy and too weak to engage in the redistribution that is needed to

create a fair society. But we have a state that is still large enough

and distorted enough that it can provide a bounty of gifts to the

wealthy.

—Joseph Stiglitz

The study found the decline in progressivity since 1960 was due to

the shift from allocation of corporate income taxes among labor and

capital to the effects of the individual income tax. Paul Krugman also supports this claim saying, "The overall tax rate on these high income families fell from 36.5% in 1980 to 26.7% in 1989."

From the White House's own analysis, the federal tax burden for

those making greater than $250,000 fell considerably during the late

1980s, 1990s and 2000s, from an effective tax of 35% in 1980, down to

under 30% from the late 1980s to 2011.

Many studies argue that tax changes of S corporations

confound the statistics prior to 1990. However, even after these

changes inflation-adjusted average after-tax income grew by 25% between

1996 and 2006 (the last year for which individual income tax data is

publicly available). This average increase, however, obscures a great

deal of variation. The poorest 20% of tax filers experienced a 6%

reduction in income while the top 0.1 percent of tax filers saw their

income almost double. Tax filers in the middle

of the income distribution experienced about a 10% increase in income.

Also during this period, the proportion of income from capital increased

for the top 0.1 percent from 64% to 70%.

Transfer payments

Transfer

payments refer to payments to persons such as social security,

unemployment compensation, or welfare. CBO reported in November 2014

that: "Government transfers reduce income inequality because the

transfers received by lower-income households are larger relative to

their market income than are the transfers received by higher-income

households. Federal taxes also reduce income inequality, because the

taxes paid by higher-income households are larger relative to their

before-tax income than are the taxes paid by lower-income households.

The equalizing effects of government transfers were significantly larger

than the equalizing effects of federal taxes from 1979 to 2011.

CBO also reported that less progressive tax and transfer policies

have contributed to greater after-tax income inequality: "As a result

of the diminishing effect of transfers and federal taxes, the Gini index

for income after transfers and federal taxes grew by more than the

index for market income. Between 1979 and 2007, the Gini index for

market income increased by 23 percent, the index for market income after

transfers increased by 29 percent, and the index for income measured

after transfers and federal taxes increased by 33 percent."

Tax expenditures

CBO charts describing amount and distribution of top 10 tax expenditures (i.e., exemptions, deductions, and preferential rates)

Tax expenditures (i.e., exclusions, deductions, preferential tax

rates, and tax credits) cause revenues to be much lower than they would

otherwise be for any given tax rate structure. The benefits from tax

expenditures, such as income exclusions for healthcare insurance

premiums paid for by employers and tax deductions for mortgage interest,

are distributed unevenly across the income spectrum. They are often

what the Congress offers to special interests in exchange for their

support. According to a report from the CBO that analyzed the 2013 data:

- The top 10 tax expenditures totalled $900 billion. This is a proxy for how much they reduced revenues or increased the annual budget deficit.

- Tax expenditures tend to benefit those at the top and bottom of the income distribution, but less so in the middle.

- The top 20% of income earners received approximately 50% of the benefit from them; the top 1% received 17% of the benefits.

- The largest single tax expenditure was the exclusion from income of employer sponsored health insurance ($250 billion).

- Preferential tax rates on capital gains and dividends were $160 billion; the top 1% received 68% of the benefit or $109 billion from lower income tax rates on these types of income.

Understanding how each tax expenditure is distributed across the income spectrum can inform policy choices.

Other causes

Shifts in political power

Paul Krugman

wrote in 2015 that: "Economists struggling to make sense of economic

polarization are, increasingly, talking not about technology but about

power." This market power hypothesis basically asserts that market power

has concentrated in monopolies and oligopolies that enable unusual amounts of income ("rents")

to be transferred from the many consumers to relatively few owners.

This hypothesis is consistent with higher corporate profits without a

commensurate rise in investment, as firms facing less competition choose

to pass a greater share of their profits to shareholders (such as

through share buybacks and dividends) rather than re-invest in the

business to ward off competitors.

One cause of this concentration of market power was the rightward

shift in American politics toward more conservative policies since

1980, as politics plays a big role in how market power can be exercised.

Policies that removed barriers to monopoly and oligopoly included

anti-union laws, reduced anti-trust activity, deregulation (or failure

to regulate) non-depository banking, contract laws that favored

creditors over debtors, etc. Further, rising wealth concentration can be

used to purchase political influence, creating a feedback loop.

Decline of unions

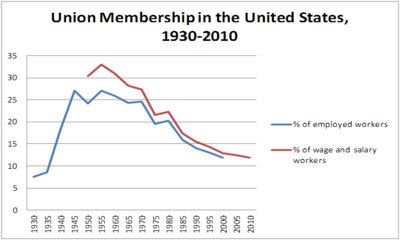

Union membership in the United States from the Great Depression to current day. (Source: Union Membership Trends in the United States, Table A-1 Appendix A for 1930 to 2000; Bureau of Labor Statistics for 2005 and 2010.)

The era of inequality growth has coincided with a dramatic decline in

labor union membership from 20% of the labor force in 1983 to about 12%

in 2007.

Classical and neoclassical economists have traditionally thought that

since the chief purpose of a union is to maximize the income of its

members, a strong but not all-encompassing union movement would lead to

increased income inequality. However, given the increase in income

inequality of the past few decades, either the sign of the effect must

be reversed, or the magnitude of the effect must be small and a much

larger opposing force has overridden it.

The decline in unionization in recent decades has fed the rise in incomes at the top.

—2015 IMF report

However, more recently, research has shown that unions' ability to

reduce income disparities among members outweighed other factors and its

net effect has been to reduce nationendal income inequality. The decline of unions has hurt this leveling effect among men, and one economist (Berkeley economist David Card) estimating about 15–20% of the "Great Divergence" among that gender is the result of declining unionization.

According to scholars, "As organized labor's political power

dissipates, economic interests in the labor market are dispersed and

policy makers have fewer incentives to strengthen unions or otherwise

equalize economic rewards."

Unions were a balancing force, helping ensure wages kept up with

productivity and that neither executives nor shareholders were unduly

rewarded. Further, societal norms placed constraints on executive pay.

This changed as union power declined (the share of unionized workers

fell significantly during the Great Divergence, from over 30% to around

12%) and CEO pay skyrocketed (rising from around 40 times the average

workers pay in the 1970s to over 350 times in the early 2000s). A 2015 report by the International Monetary Fund

also attributes the decline of labor's share of GDP to deunionization,

noting the trend "necessarily increases the income share of corporate

managers' pay and shareholder returns ... Moreover, weaker unions can

reduce workers' influence on corporate decisions that benefit top

earners, such as the size and structure of top executive compensation."

Still other researchers think it is the labor movement's loss of

national political power to promote equalizing "government intervention

and changes in private sector behavior" has had the greatest impact on

inequality in the US.

Sociologist Jake Rosenfeld of the University of Washington argues that

labor unions were the primary institution fighting inequality in the

United States and helped grow a multiethnic middle class, and their

decline has resulted in diminishing prospects for U.S. workers and their

families. Timothy Noah estimates the "decline" of labor union power "responsible for 20%" of the Great Divergence. While the decline of union power in the US has been a factor in declining middle class incomes, they have retained their clout in Western Europe. In Denmark, influential trade unions such as Fagligt Fælles Forbund (3F) ensure that fast-food workers earn a living wage, the equivalent of $20 an hour, which is more than double the hourly rate for their counterparts in the United States.

Critics of technological change as an explanation for the "Great Divergence" of income levels in America point to public policy and party politics, or "stuff the government did, or didn't do".

They argue these have led to a trend of declining labor union

membership rates and resulting diminishing political clout, decreased

expenditure on social services, and less government redistribution.

Moreover, the United States is the only advanced economy without a labor-based political party.

As of 2011, several state legislatures have launched initiatives

aimed at lowering wages, labor standards, and workplace protections for

both union and non-union workers.

The economist Joseph Stiglitz

argues that "Strong unions have helped to reduce inequality, whereas

weaker unions have made it easier for CEOs, sometimes working with

market forces that they have helped shape, to increase it." The long

fall in unionization in the U.S. since WWII has seen a corresponding rise in the inequality of wealth and income.

A study by Kristal and Cohen reported that rising wage inequality was

driven more by declining unions and the fall in the real value of the

minimum wage, with twice as much impact as technology.

Political parties and presidents

Liberal political scientist Larry Bartels has found a strong correlation between the party of the president and income inequality in America since 1948. (see below) Examining average annual pre-tax income growth from 1948 to 2005 (which encompassed most of the egalitarian Great Compression and the entire inegalitarian Great Divergence) Bartels shows that under Democratic presidents (from Harry Truman

forward), the greatest income gains have been at the bottom of the

income scale and tapered off as income rose. Under Republican

presidents, in contrast, gains were much less but what growth there was

concentrated towards the top, tapering off as you went down the income

scale.

Summarizing Bartels's findings, journalist Timothy Noah referred to the administrations of Democratic presidents as "Democrat-world", and GOP administrations as "Republican-world":

In Democrat-world, pre-tax income increased 2.64% annually for the poor and lower-middle-class and 2.12% annually for the upper-middle-class and rich. There was no Great Divergence. Instead, the Great Compression – the egalitarian income trend that prevailed through the 1940s, 1950s, and 1960s – continued to the present, albeit with incomes converging less rapidly than before. In Republican-world, meanwhile, pre-tax income increased 0.43 percent annually for the poor and lower-middle-class and 1.90 percent for the upper-middle-class and rich. Not only did the Great Divergence occur; it was more greatly divergent. Also of note: In Democrat-world pre-tax income increased faster than in the real world not just for the 20th percentile but also for the 40th, 60th, and 80th. We were all richer and more equal! But in Republican-world, pre-tax income increased slower than in the real world not just for the 20th percentile but also for the 40th, 60th, and 80th. We were all poorer and less equal! Democrats also produced marginally faster income growth than Republicans at the 95th percentile, but the difference wasn't statistically significant.

The pattern of distribution of growth appears to be the result of a whole host of policies,

including not only the distribution of taxes and benefits but also the government's stance toward unions, whether the minimum wage rises, the extent to which the government frets about inflation versus too-high interest rates, etc., etc.

Noah admits the evidence of this correlation is "circumstantial

rather than direct", but so is "the evidence that smoking is a leading

cause of lung cancer."

In his 2017 book The Great Leveler, historian Walter Scheidel point out that, starting in the 1970s, both parties shifted towards promoting free market capitalism,

with Republicans moving further to the political right than Democrats

to the political left. He notes that Democrats have been instrumental in

the financial deregulation of the 1990s and have largely neglected

social welfare issues while increasingly focusing on issues pertaining

to identity politics. The Clinton Administration in particular continued promoting free market, or neoliberal, reforms which began under the Reagan Administration.

Non-party political action

Ratio

of average compensation of CEOs and production workers, 1965–2009.

Source: Economic Policy Institute. 2011. Based on data from Wall Street

Journal/Mercer, Hay Group 2010.

According to political scientists Jacob Hacker and Paul Pierson writing in the book Winner-Take-All Politics,

the important policy shifts were brought on not by the Republican Party

but by the development of a modern, efficient political system,

especially lobbying, by top earners – and particularly corporate executives and the financial services industry.

The end of the 1970s saw a transformation of American politics away

from a focus on the middle class, with new, much more effective,

aggressive and well-financed lobbyists and pressure groups acting on

behalf of upper income groups. Executives

successfully eliminated any countervailing power or oversight of

corporate managers (from private litigation, boards of directors and

shareholders, the Securities and Exchange Commission or labor unions).

The financial industry's success came from successfully pushing

for deregulation of financial markets, allowing much more lucrative but

much more risky investments from which it privatized the gains while

socializing the losses with government bailouts.

(the two groups formed about 60% of the top 0.1 percent of earners.)

All top earners were helped by deep cuts in estate and capital gains

taxes, and tax rates on high levels of income.

Arguing against the proposition that the explosion in pay for

corporate executives – which grew from 35X average worker pay in 1978 to

over 250X average pay before the 2007 recession

– is driven by an increased demand for scarce talent and set according

to performance, Krugman points out that multiple factors outside of

executives' control govern corporate profitability, particularly in

short term when the head of a company like Enron

may look like a great success. Further, corporate boards follow other

companies in setting pay even if the directors themselves disagree with

lavish pay "partly to attract executives whom they consider adequate,

partly because the financial market will be suspicious of a company

whose CEO isn't lavishly paid." Finally "corporate boards, largely

selected by the CEO, hire compensation experts, almost always chosen by

the CEO" who naturally want to please their employers.

Lucian Arye Bebchuk, Jesse M. Fried, the authors of Pay Without Performance, critique of executive pay,

argue that executive capture of corporate governance is so complete

that only public relations, i.e. public `outrage`, constrains their pay.

This in turn has been reduced as traditional critics of excessive pay –

such as politicians (where need for campaign contributions from the

richest outweighs populist indignation), media (lauding business

genius), unions (crushed) – are now silent.

In addition to politics, Krugman postulated change in norms of

corporate culture have played a factor. In the 1950s and 60s, corporate

executives had (or could develop) the ability to pay themselves very

high compensation through control of corporate boards of directors, they

restrained themselves. But by the end of the 1990s, the average real

annual compensation of the top 100 C.E.O.'s skyrocketed from $1.3

million – 39 times the pay of an average worker – to $37.5 million, more

than 1,000 times the pay of ordinary workers from 1982 to 2002. Journalist George Packer

also sees the dramatic increase in inequality in America as a product

of the change in attitude of the American elite, which (in his view) has

been transitioning itself from pillars of society to a special interest

group.

Author Timothy Noah estimates that what he calls "Wall Street and

corporate boards' pampering" of the highest earning 0.1% is "responsible

for 30%" of the post-1978 increase in inequality.

Immigration

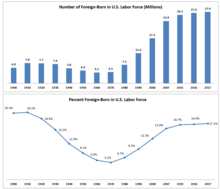

Foreign-born in US labor force 1900-2015

The Immigration and Nationality Act of 1965 increased immigration to America, especially of non-Europeans.

From 1970 to 2007, the foreign-born proportion of America's population

grew from 5% to 11%, most of whom had lower education levels and

incomes than native-born Americans. But the contribution of this

increase in supply of low-skill labor seem to have been relatively

modest. One estimate stated that immigration reduced the average annual

income of native-born "high-school dropouts" ("who roughly correspond to

the poorest tenth of the workforce") by 7.4% from 1980 to 2000. The

decline in income of better educated workers was much less. Author Timothy Noah estimates that "immigration" is responsible for just 5% of the "Great Divergence" in income distribution, as does economist David Card.

While immigration was found to have slightly depressed the wages

of the least skilled and least educated American workers, it doesn't

explain rising inequality among high school and college graduates. Scholars such as political scientists Jacob S. Hacker, Paul Pierson, Larry Bartels

and Nathan Kelly, and economist Timothy Smeeding question the

explanation of educational attainment and workplace skills point out

that other countries with similar education levels and economies have

not gone the way of the US, and that the concentration of income in the

US hasn't followed a pattern of "the 29% of Americans with college

degrees pulling away" from those who have less education.

Wage theft

A September 2014 report by the Economic Policy Institute claims wage theft

is also responsible for exacerbating income inequality: "Survey

evidence suggests that wage theft is widespread and costs workers

billions of dollars a year, a transfer from low-income employees to

business owners that worsens income inequality, hurts workers and their

families, and damages the sense of fairness and justice that a democracy

needs to survive."

Corporatism

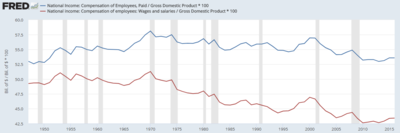

Labor's

share of GDP has declined 1970 to 2013, measured based on total

compensation as well as salaries & wages. This implies capital's

share is increasing.

Edmund Phelps,

published an analysis in 2010 theorizing that the cause of income

inequality is not free market capitalism, but instead is the result of

the rise of corporatism.

Corporatism, in his view, is the antithesis of free market capitalism.

It is characterized by semi-monopolistic organizations and banks, big

employer confederations, often acting with complicit state institutions

in ways that discourage (or block) the natural workings of a free

economy. The primary effects of corporatism are the consolidation of

economic power and wealth with end results being the attrition of

entrepreneurial and free market dynamism.

His follow-up book, Mass Flourishing, further defines

corporatism by the following attributes: power-sharing between

government and large corporations (exemplified in the U.S. by widening

government power in areas such as financial services, healthcare, and

energy through regulation), an expansion of corporate lobbying and

campaign support in exchange for government reciprocity, escalation in

the growth and influence of financial and banking sectors, increased

consolidation of the corporate landscape through merger and acquisition

(with ensuing increases in corporate executive compensation), increased

potential for corporate/government corruption and malfeasance, and a

lack of entrepreneurial and small business development leading to

lethargic and stagnant economic conditions.

Today, in the United States, virtually all of these economic

conditions are being borne out. With regard to income inequality, the

2014 income analysis of University of California, Berkeley economist Emmanuel Saez

confirms that relative growth of income and wealth is not occurring

among small and mid-sized entrepreneurs and business owners (who

generally populate the lower half of top one per-centers in income),

but instead only among the top .1 percent of income distribution ...

whom Paul Krugman describes as "super-elites - corporate bigwigs and

financial wheeler-dealers." ... who earn $2,000,000 or more every year.

For example, measured relative to GDP, total compensation and its

component wages and salaries have been declining since 1970. This

indicates a shift in income from labor (persons who derive income from

hourly wages and salaries) to capital (persons who derive income via

ownership of businesses, land and assets).

Wages and salaries have fallen from approximately 51% GDP in 1970 to

43% GDP in 2013. Total compensation has fallen from approximately 58%

GDP in 1970 to 53% GDP in 2013.

To put this in perspective, five percent of U.S. GDP was approximately

$850 billion in 2013. This represents an additional $7,000 in wages and

salaries for each of the 120 million U.S. households. Larry Summers

estimated in 2007 that the lower 80% of families were receiving $664

billion less income than they would be with a 1979 income distribution

(a period of much greater equality), or approximately $7,000 per family.

Not receiving this income may have led many families to increase their debt burden, a significant factor in the 2007-2009 subprime mortgage crisis,

as highly leveraged homeowners suffered a much larger reduction in

their net worth during the crisis. Further, since lower income families

tend to spend relatively more of their income than higher income

families, shifting more of the income to wealthier families may slow

economic growth.

In another example, The Economist

propounds that a swelling corporate financial and banking sector has

caused Gini Coefficients to rise in the U.S. since 1980: "Financial

services' share of GDP in America doubled to 8% between 1980 and 2000;

over the same period their profits rose from about 10% to 35% of total

corporate profits, before collapsing in 2007–09. Bankers are being paid

more, too. In America the compensation of workers in financial services

was similar to average compensation until 1980. Now it is twice that

average."

The summary argument, considering these findings, is that if

corporatism is the consolidation and sharing of economic and political

power between large corporations and the state ... then a corresponding

concentration of income and wealth (with resulting income inequality) is

an expected by-product of such a consolidation.

Neoliberalism

Some economists, sociologists and anthropologists argue that neoliberalism, or the resurgence of 19th century theories relating to laissez-faire economic liberalism in the late 1970s, has been the significant driver of inequality. More broadly, according to The Handbook of Neoliberalism,

the term has "become a means of identifying a seemingly ubiquitous set

of market-oriented policies as being largely responsible for a wide

range of social, political, ecological and economic problems." Vicenç Navarro points to policies pertaining to the deregulation of labor markets, privatization of public institutions, union busting and reduction of public social expenditures as contributors to this widening disparity.

The privatization of public functions, for example, grows income

inequality by depressing wages and eliminating benefits for middle class

workers while increasing income for those at the top.

The deregulation of the labor market undermined unions by allowing the

real value of the minimum wage to plummet, resulting in employment

insecurity and widening wage and income inequality. David M. Kotz, professor of economics at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, contends that neoliberalism "is based on the thorough domination of labor by capital."

As such, the advent of the neoliberal era has seen a sharp increase in

income inequality through the decline of unionization, stagnant wages

for workers and the rise of CEO supersalaries. According to Emmanuel Saez:

The labor market has been creating much more inequality over the last thirty years, with the very top earners capturing a large fraction of macroeconomic productivity gains. A number of factors may help explain this increase in inequality, not only underlying technological changes but also the retreat of institutions developed during the New Deal and World War II - such as progressive tax policies, powerful unions, corporate provision of health and retirement benefits, and changing social norms regarding pay inequality.

Pennsylvania State University

political science professor Pamela Blackmon attributes the trends of

growing poverty and income inequality to the convergence of several

neoliberal policies during Ronald Reagan's presidency,

including the decreased funding of education, decreases in the top

marginal tax rates, and shifts in transfer programs for those in

poverty. Journalist Mark Bittman echoes this sentiment in a 2014 piece for The New York Times:

The progress of the last 40 years has been mostly cultural, culminating, the last couple of years, in the broad legalization of same-sex marriage. But by many other measures, especially economic, things have gotten worse, thanks to the establishment of neo-liberal principles — anti-unionism, deregulation, market fundamentalism and intensified, unconscionable greed — that began with Richard Nixon and picked up steam under Ronald Reagan. Too many are suffering now because too few were fighting then.

Fred L. Block and Margaret Somers, in expanding on Karl Polanyi's critique of laissez-faire theories in The Great Transformation,

argue that Polanyi's analysis helps to explain why the revival of such

ideas has contributed to the "persistent unemployment, widening

inequality, and the severe financial crises that have stressed Western

economies over the past forty years." John Schmitt and Ben Zipperer of the Center for Economic and Policy Research

also point to economic liberalism as one of the causes of income

inequality. They note that European nations, in particular the social democracies of Northern Europe with extensive and well funded welfare states, have lower levels of income inequality and social exclusion than the United States.