Hotel union workers strike with the slogan "One job should be enough"

| |

| National organization(s) | AFL-CIO, CtW, IWW |

|---|---|

| Regulatory authority | United States Department of Labor National Labor Relations Board |

| Primary legislation | National Labor Relations Act Taft-Hartley Act |

| Total union membership | 14.6 million |

| Percentage of workforce; | ▪ Total: 10.3% ▪ Public sector: 33.6% ▪ Private sector: 6.2% Demographics ▪ Age 16–24: 4.4% ▪ 25–34: 8.8% ▪ 35–44: 11.8% ▪ 45–54: 12.6% ▪ 55–64: 12.7% ▪ 65 and over: 9.7% ▪ Women: 9.7% ▪ Men: 10.8% |

| Standard Occupational Classification | ▪ Management, professional:

11.9% ▪ Service: 9.2% ▪ Sales and office: 6.5% ▪ Natural resources, construction, and maintenance: 15.3% ▪ Production, transportation, and material moving: 14.8% |

| International Labour Organization | |

| United States is a member of the ILO | |

| Convention ratification | |

| Freedom of Association | Not ratified |

| Right to Organise | Not ratified |

Labor unions in the United States are organizations that represent workers in many industries recognized under US labor law. Their activity today centers on collective bargaining over wages, benefits, and working conditions for their membership, and on representing their members in disputes with management over violations of contract provisions. Larger trade unions also typically engage in lobbying activities and electioneering at the state and federal level.

Most unions in the United States are aligned with one of two larger umbrella organizations: the AFL-CIO created in 1955, and the Change to Win Federation which split from the AFL-CIO in 2005. Both advocate policies and legislation on behalf of workers in the United States and Canada, and take an active role in politics. The AFL-CIO is especially concerned with global trade issues.

In 2019, there were 14.6 million members in the U.S., down from 17.7 million in 1983. The percentage of workers belonging to a union in the United States (or total labor union "density") was 10.3%, compared to 20.1% in 1983. Union membership in the private sector has fallen to 6.2%, one fifth that of public sector workers, at 33.6%. Over half of all union members in the U.S. lived in just seven states (California, New York, Illinois, Pennsylvania, New Jersey, Ohio, and Washington), though these states accounted for only about one-third of the workforce. From a global perspective, in 2016 the US had the fifth lowest trade union density of the 36 OECD member nations.

In the 21st century the most prominent unions are among public sector employees such as city employees, government workers, teachers and police. Members of unions are disproportionately older, male, and residents of the Northeast, the Midwest, and California. Union workers average 10-30% higher pay than non-union in the United States after controlling for individual, job, and labor market characteristics.

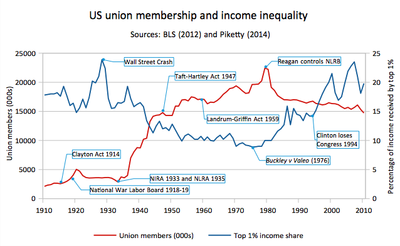

Although much smaller compared to their peak membership in the 1950s, American unions remain a political factor, both through mobilization of their own memberships and through coalitions with like-minded activist organizations around issues such as immigrant rights, trade policy, health care, and living wage campaigns. Of special concern are efforts by cities and states to reduce the pension obligations owed to unionized workers who retire in the future. Republicans elected with Tea Party support in 2010, most notably former Governor Scott Walker of Wisconsin, have launched major efforts against public sector unions due in part to state government pension obligations (even though Wisconsin's state pension is 100% funded as of 2015) along with the allegation that the unions are too powerful. The academic literature shows substantial evidence that labor unions reduce economic inequality. Research indicates that rising income inequality in the United States is partially attributable to the decline of the labor movement and union membership.

History

Knights of Labor's seal: "An injury to one is a concern to all."

Unions began forming in the mid-19th century in response to the social and economic impact of the Industrial Revolution. National labor unions began to form in the post-Civil War Era. The Knights of Labor

emerged as a major force in the late 1880s, but it collapsed because of

poor organization, lack of effective leadership, disagreement over

goals, and strong opposition from employers and government forces.

The American Federation of Labor, founded in 1886 and led by Samuel Gompers

until his death in 1924, proved much more durable. It arose as a loose

coalition of various local unions. It helped coordinate and support

strikes and eventually became a major player in national politics,

usually on the side of the Democrats.

American labor unions benefited greatly from the New Deal policies of Franklin Delano Roosevelt in the 1930s. The Wagner Act,

in particular, legally protected the right of unions to organize.

Unions from this point developed increasingly closer ties to the

Democratic Party, and are considered a backbone element of the New Deal Coalition.

Post-WWII

Political cartoon showing organized labor marching towards progress, while a shortsighted employer tries to stop labor (1913)

Pro-business conservatives gained control of Congress in 1946, and in 1947 passed the Taft-Hartley Act, drafted by Senator Robert A. Taft. President Truman vetoed it but the Conservative coalition

overrode the veto. The veto override had considerable Democratic

support, including 106 out of 177 Democrats in the House, and 20 out of

42 Democrats in the Senate.

The law, which is still in effect, banned union contributions to

political candidates, restricted the power of unions to call strikes

that "threatened national security," and forced the expulsion of

Communist union leaders (the Supreme Court found the anti-communist

provision to be unconstitutional, and it is no longer in force). The

unions campaigned vigorously for years to repeal the law but failed.

During the late 1950s, the Landrum Griffin Act of 1959 passed in the wake of Congressional investigations of corruption and undemocratic internal politics in the Teamsters and other unions.

In 1955, the two largest labor organizations, the AFL and CIO,

merged, ending a division of over 20 years. AFL President George Meany

became President of the new AFL-CIO, and AFL Secretary-Treasurer William

Schnitzler became AFL-CIO Secretary-Treasurer. The draft constitution

was primarily written by AFL Vice President Matthew Woll and CIO General Counsel Arthur Goldberg,

while the joint policy statements were written by Woll, CIO

Secretary-Treasurer James Carey, CIO vice presidents David McDonald and Joseph Curran, Brotherhood of Railway Clerks President George Harrison, and Illinois AFL-CIO President Reuben Soderstrom.

The percentage of workers belonging to a union (or "density") in

the United States peaked in 1954 at almost 35% (citation needed) and the

total number of union members peaked in 1979 at an estimated 21.0

million. Membership has declined since, with private sector union

membership beginning a steady decline that continues into the 2010s, but

the membership of public sector unions grew steadily.

Labor union voting by federal workers at the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (1948)

After 1960 public sector unions grew rapidly and secured good wages

and high pensions for their members. While manufacturing and farming

steadily declined, state- and local-government employment quadrupled

from 4 million workers in 1950 to 12 million in 1976 and 16.6 million in

2009. Adding in the 3.7 million federal civilian employees, in 2010 8.4 million government workers were represented by unions, including 31% of federal workers, 35% of state workers and 46% of local workers.

By the 1970s, a rapidly increasing flow of imports (such as

automobiles, steel and electronics from Germany and Japan, and clothing

and shoes from Asia) undercut American producers.

By the 1980s there was a large-scale shift in employment with fewer

workers in high-wage sectors and more in the low-wage sectors. Many companies closed or moved factories to Southern states (where unions were weak), countered the threat of a strike by threatening to close or move a plant, or moved their factories offshore to low-wage countries. The number of major strikes and lockouts fell by 97% from 381 in 1970 to 187 in 1980 to only 11 in 2010.

On the political front, the shrinking unions lost influence in the

Democratic Party, and pro-Union liberal Republicans faded away.

Union membership among workers in private industry shrank

dramatically, though after 1970 there was growth in employees unions of

federal, state and local governments. The intellectual mood in the 1970s and 1980s favored deregulation and free competition.

Numerous industries were deregulated, including airlines, trucking,

railroads and telephones, over the objections of the unions involved. The climax came when President Ronald Reagan—a former union president—broke the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization (PATCO) strike in 1981, dealing a major blow to unions.

Republicans began to push through legislative blueprints to curb

the power of public employee unions as well as eliminate business

regulations.

Labor unions today

Union members rally to reject union busting in New Orleans (2019)

Today most labor unions (or trade unions) in the United States are members of one of two larger umbrella organizations: the American Federation of Labor–Congress of Industrial Organizations (AFL-CIO) or the Change to Win Federation,

which split from the AFL-CIO in 2005-2006. Both organizations advocate

policies and legislation favorable to workers in the United States and

Canada, and take an active role in politics favoring the Democratic

party but not exclusively so. The AFL-CIO is especially concerned with global trade and economic issues.

Private sector unions are regulated by the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), passed in 1935 and amended since then. The law is overseen by the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB), an independent federal agency.

Public sector unions are regulated partly by federal and partly by

state laws. In general they have shown robust growth rates, because

wages and working conditions are set through negotiations with elected

local and state officials.

To join a traditional labor union, workers must either be given

voluntary recognition from their employer or have a majority of workers

in a bargaining unit vote for union representation. In either case, the government must then certify the newly formed union. Other forms of unionism include minority unionism, solidarity unionism, and the practices of organizations such as the Industrial Workers of the World, which do not always follow traditional organizational models.

Public sector worker unions are governed by labor laws and labor

boards in each of the 50 states. Northern states typically model their

laws and boards after the NLRA and the NLRB. In other states, public

workers have no right to establish a union as a legal entity. (About 40%

of public employees in the USA do not have the right to organize a

legally established union.)

A review conducted by the federal government on pay scale shows

that employees in a labor union earn up to 33% more income than their

nonunion counterparts, as well as having more job security, and safer

and higher-quality work conditions. The median weekly income for union workers was $973 in 2014, compared with $763 for nonunion workers.

Labor negotiations

Once

the union won the support of a majority of the bargaining unit and is

certified in a workplace, it has the sole authority to negotiate the

conditions of employment. Under the NLRA, employees can also, if there

is no majority support, form a minority union which represents the rights of only those members who choose to join.

Businesses, however, do not have to recognize the minority union as a

collective bargaining agent for its members, and therefore the minority

union's power is limited.

This minority model was once widely used, but was discarded when unions

began to consistently win majority support. Unions are beginning to

revisit the members-only model of unionism, because of new changes to

labor law, which unions view as curbing workers' ability to organize.

The employer and the union write the terms and conditions of

employment in a legally binding contract. When disputes arise over the

contract, most contracts call for the parties to resolve their

differences through a grievance process to see if the dispute can be

mutually resolved. If the union and the employer still cannot settle the

matter, either party can choose to send the dispute to arbitration, where the case is argued before a neutral third party.

Worker slogan used during the 2011 Wisconsin protests

Right-to-work statutes forbid unions from negotiating union shops and agency shops. Thus, while unions do exist in "right-to-work" states, they are typically weaker.

Members of labor unions enjoy "Weingarten Rights."

If management questions the union member on a matter that may lead to

discipline or other changes in working conditions, union members can

request representation by a union representative. Weingarten Rights are named for the first Supreme Court decision to recognize those rights.

The NLRA goes farther in protecting the right of workers to

organize unions. It protects the right of workers to engage in any

"concerted activity" for mutual aid or protection. Thus, no union

connection is needed. Concerted activity "in its inception involves only

a speaker and a listener, for such activity is an indispensable

preliminary step to employee self-organization."

Unions are currently advocating new federal legislation, the Employee Free Choice Act (EFCA), that would allow workers to elect union representation by simply signing a support card (card check).

The current process established by federal law requires at least 30% of

employees to sign cards for the union, then wait 45 to 90 days for a

federal official to conduct a secret ballot election in which a simple majority of the employees must vote for the union in order to obligate the employer to bargain.

Unions report that, under the present system, many employers use

the 45- to 90-day period to conduct anti-union campaigns. Some opponents

of this legislation fear that removing secret balloting from the

process will lead to the intimidation and coercion of workers on behalf

of the unions. During the 2008 elections, the Employee Free Choice Act

had widespread support of many legislators in the House and Senate, and

of the President. Since then, support for the "card check" provisions

of the EFCA subsided substantially.

Membership

Rise and fall of union membership density in the US by percent of industry

Union membership had been declining in the US since 1954, and since 1967, as union membership rates decreased, middle class incomes shrank correspondingly.

In 2007, the labor department reported the first increase in union

memberships in 25 years and the largest increase since 1979. Most of the

recent gains in union membership have been in the service sector while

the number of unionized employees in the manufacturing sector has

declined. Most of the gains in the service sector have come in West

Coast states like California where union membership is now at 16.7%

compared with a national average of about 12.1%.

Historically, the rapid growth of public employee unions since the

1960s has served to mask an even more dramatic decline in private-sector

union membership.

At the apex of union density in the 1940s, only about 9.8% of

public employees were represented by unions, while 33.9% of private,

non-agricultural workers had such representation. In this decade, those

proportions have essentially reversed, with 36% of public workers being

represented by unions while private sector union density had plummeted

to around 7%. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics most recent survey

indicates that union membership in the US has risen to 12.4% of all

workers, from 12.1% in 2007. For a short period, private sector union

membership rebounded, increasing from 7.5% in 2007 to 7.6% in 2008.

However, that trend has since reversed. In 2013 there were 14.5

million members in the U.S., compared with 17.7 million in 1983. In

2013, the percentage of workers belonging to a union was 11.3%, compared

to 20.1% in 1983. The rate for the private sector was 6.4%, and for the

public sector 35.3%.

In the ten years 2005 through 2014, the National Labor Relations Board

recorded 18,577 labor union representation elections; in 11,086 of

these elections (60 percent), the majority of workers voted for union

representation. Most of the elections (15,517) were triggered by

employee petitions for representation, of which unions won 9,933. Less

common were elections caused by employee petitions for decertification

(2792, of which unions won 1070), and employer-filed petitions for

either representation or decertification (268, of which unions won 85).

Labor education programs

Union members protest against another government shutdown (2019)

In the US, labor education programs such as the Harvard Trade Union Program created in 1942 by Harvard University professor John Thomas Dunlop

sought to educate union members to deal with important contemporary

workplace and labor law issues of the day. The Harvard Trade Union

Program is currently part of a broader initiative at Harvard Law School called the Labor and Worklife Program that deals with a wide variety of labor and employment issues from union pension investment funds to the effects of nanotechnology on labor markets and the workplace.

Cornell University is known to be one of the leading centers for labor education in the world, establishing the Cornell University School of Industrial and Labor Relations

in 1945. The school's mission is to prepare leaders, inform national

and international employment and labor policy, and improve working lives

through undergraduate and graduate education. The school publishes the Industrial and Labor Relations Review and had Frances Perkins on its faculty. The school has six academic departments: Economics, Human Resource Management, International and Comparative Labor, Labor Relations, Organizational Behavior, and Social Statistics. Classes include "Politics of the Global North" and "Economic Analysis of the University."

Jurisdiction

Labor unions use the term jurisdiction

to refer to their claims to represent workers who perform a certain

type of work and the right of their members to perform such work. For

example, the work of unloading containerized cargo at United States ports, which the International Longshoremen's Association, the International Longshore and Warehouse Union and the International Brotherhood of Teamsters have claimed rightfully should be assigned to workers they represent. A jurisdictional strike

is a concerted refusal to work undertaken by a union to assert its

members' right to such job assignments and to protest the assignment of

disputed work to members of another union or to unorganized workers.

Jurisdictional strikes occur most frequently in the United States in the

construction industry.

Unions also use jurisdiction to refer to the geographical

boundaries of their operations, as in those cases in which a national or

international union allocates the right to represent workers among

different local unions based on the place of those workers' employment,

either along geographical lines or by adopting the boundaries between

political jurisdictions.

Public opinion

Although

not as overwhelmingly supportive as it was from the 1930s through the

early 1960s, a clear majority of the American public approves of labor

unions. The Gallup organization has tracked public opinion of unions

since 1936, when it found that 72 percent approved of unions. The

overwhelming approval declined in the late 1960s, but - except for one

poll in 2009 in which the unions received a favorable rating by only 48

percent of those interviewed, majorities have always supported labor

unions. A Gallup Poll released August 2018 showed 62% of respondents

approving unions, the highest level in over a decade. Disapproval of

unions was expressed by 32%.

On the question of whether or not unions should have more

influence or less influence, Gallup has found the public consistently

split since Gallup first posed the question in 2000, with no majority

favoring either more influence or less influence. In August 2018, 39

percent wanted unions to have more influence, 29 percent less influence,

with 26 percent wanting the influence of labor unions to remain about

the same.

A Pew Research Center poll from 2009-2010 found a drop of Labor Union support in the midst of The Great Recession sitting at 41% Favorable 40% unfavorable. 8 years later in 2018, Union support rose to 55% Favorable 33% Unfavorable Despite this Union membership had continued to fall.

Possible causes of drop in membership

As union membership declined income inequality rose. The US does not require employee representatives on boards of directors, or elected work councils.

Although most industrialized

countries have seen a drop in unionization rates, the drop in union

density (the unionized proportion of the working population) has been

more significant in the United States than elsewhere.

Global trends

The

US Bureau of Labor Statistics surveyed the histories of union

membership rates in industrialized countries from 1970 to 2003, and

found that of 20 advanced economies which had union density statistics

going back to 1970, 16 of them had experienced drops in union density

from 1970 to 2003. Over the same period during which union density in

the US declined from 23.5 percent to 12.4 percent, some counties saw

even steeper drops. Australian unionization fell from 50.2 percent in

1970 to 22.9 percent in 2003, in New Zealand it dropped from 55.2

percent to 22.1 percent, and in Austria union participation fell from

62.8 percent down to 35.4 percent. All the English-speaking countries

studied saw union membership decline to some degree. In the United

Kingdom, union participation fell from 44.8 percent in 1970 to 29.3

percent in 2003. In Ireland the decline was from 53.7 percent down to

35.3 percent. Canada had one of the smallest declines over the period,

going from 31.6 percent in 1970 to 28.4 percent in 2003. Most of the

countries studied started in 1970 with higher participation rates than

the US, but France, which in 1970 had a union participation rate of 21.7

percent, by 2003 had fallen to 8.3 percent. The remaining four

countries which had gained in union density were Finland, Sweden,

Denmark, and Belgium.

Popularity

Public approval of unions climbed during the 1980s much as it did in other industrialized nations,[64] but declined to below 50% for the first time in 2009 during the Great Recession.

It is not clear if this is a long term trend or a function of a high

unemployment rate which historically correlates with lower public

approval of labor unions.

One explanation for loss of public support is simply the lack of

union power or critical mass. No longer do a sizable percentage of

American workers belong to unions, or have family members who do. Unions

no longer carry the "threat effect": the power of unions to raise wages

of non-union shops by virtue of the threat of unions to organize those

shops.

Polls of public opinion and labor unions

A historical comparison of union membership as a percentage of all workers and union support in the U.S.

A New York Times/CBS Poll found that 60% of Americans opposed restricting collective bargaining

while 33% were for it. The poll also found that 56% of Americans

opposed reducing pay of public employees compared to the 37% who

approved. The details of the poll also stated that 26% of those

surveyed, thought pay and benefits for public employees were too high,

25% thought too low, and 36% thought about right. Mark Tapscott of the Washington Examiner criticized the poll, accusing it of over-sampling union and public employee households.

A Gallup

poll released on March 9, 2011, showed that Americans were more likely

to support limiting the collective bargaining powers of state employee

unions to balance a state's budget (49%) than disapprove of such a

measure (45%), while 6% had no opinion. 66% of Republicans approved of

such a measure as did 51% of independents. Only 31% of Democrats

approved.

A Gallup

poll released on March 11, 2011, showed that nationwide, Americans were

more likely to give unions a negative word or phrase when describing

them (38%) than a positive word or phrase (34%). 17% were neutral and

12% didn't know. Republicans were much more likely to say a negative

term (58%) than Democrats (19%). Democrats were much more likely to say a

positive term (49%) than Republicans (18%).

A nationwide Gallup poll (margin of error ±4%) released on April 1, 2011, showed the following:

- When asked if they supported the labor unions or the governors in state disputes; 48% said they supported the unions, 39% said the governors, 4% said neither, and 9% had no opinion.

- Women supported the governors much less than men. 45% of men said they supported the governors, while 46% said they supported the unions. This compares to only 33% of women who said they supported the governors and 50% who said they supported the unions.

- All areas of the US (East, Midwest, South, West) were more likely to support unions than the governors. The largest gap being in the East with 35% supporting the governors and 52% supporting the unions, and the smallest gap being in the West with 41% supporting the governors and 44% the unions.

- 18- to 34-year-olds were much more likely to support unions than those over 34 years of age. Only 27% of 18- to 34-year-olds supported the governors, while 61% supported the unions. Americans ages 35 to 54 slightly supported the unions more than governors, with 40% supporting the governors and 43% the unions. Americans 55 and older were tied when asked, with 45% supporting the governors and 45% the unions.

- Republicans were much more likely to support the governors when asked with 65% supporting the governors and 25% the unions. Independents slightly supported unions more, with 40% supporting the governors and 45% the unions. Democrats were overwhelmingly in support of the unions. 70% of Democrats supported the unions, while only 19% supported the governors.

- Those who said they were following the situation not too closely or not at all supported the unions over governors, with a 14–point (45% to 31%) margin. Those who said they were following the situation somewhat closely supported the unions over governors by a 52–41 margin. Those who said that they were following the situation very closely were only slightly more likely to support the unions over the governors, with a 49-48 margin.

Unions and workers protesting together for higher wages (2015)

A nationwide Gallup poll released on August 31, 2011, revealed the following:

- 52% of Americans approved of labor unions, unchanged from 2010.

- 78% of Democrats approved of labor unions, up from 71% in 2010.

- 52% of Independents approved of labor unions, up from 49% in 2010.

- 26% of Republicans approved of labor unions, down from 34% in 2010.

A nationwide Gallup poll released on September 1, 2011, revealed the following:

- 55% of Americans believed that labor unions will become weaker in the United States as time goes by, an all-time high. This compared to 22% who said their power would stay the same, and 20% who said they would get stronger.

- The majority of Republicans and Independents believed labor unions would further weaken by a 58% and 57% percentage margin respectively. A plurality of Democrats believed the same, at 46%.

- 42% of Americans want labor unions to have less influence, tied for the all-time high set in 2009. 30% wanted more influence and 25% wanted the same amount of influence.

- The majority of Republicans wanted labor unions to have less influence, at 69%.

- A plurality of Independents wanted labor unions to have less influence, at 40%.

- A plurality of Democrats wanted labor unions to have more influence, at 45%.

- The majority of Americans believed labor unions mostly helped members of unions by a 68 to 28 margin.

- A plurality of Americans believed labor unions mostly helped the companies where workers are unionized by a 48-44 margin.

- A plurality of Americans believed labor unions mostly helped state and local governments by a 47-45 margin.

- A plurality of Americans believed labor unions mostly hurt the US economy in general by a 49-45 margin.

- The majority of Americans believed labor unions mostly hurt workers who are not members of unions by a 56-34 margin.

Institutional environments

A

broad range of forces have been identified as potential contributors to

the drop in union density across countries. Sano and Williamson outline

quantitative studies that assess the relevance of these factors across

countries.

The first relevant set of factors relate to the receptiveness of

unions' institutional environments. For example, the presence of a Ghent system

(where unions are responsible for the distribution of unemployment

insurance) and of centralized collective bargaining (organized at a

national or industry level as opposed to local or firm level) have both

been shown to give unions more bargaining power and to correlate

positively to higher rates of union density.

Unions have enjoyed higher rates of success in locations where

they have greater access to the workplace as an organizing space (as

determined both by law and by employer acceptance), and where they

benefit from a corporatist

relationship to the state and are thus allowed to participate more

directly in the official governance structure. Moreover, the

fluctuations of business cycles, particularly the rise and fall of

unemployment rates and inflation, are also closely linked to changes in

union density.

Labor legislation

Workers speak in support of the Workplace Democracy Act which makes it easier to unionize (2018)

Labor lawyer Thomas Geoghegan attributes the drop to the long-term effects of the 1947 Taft-Hartley Act,

which slowed and then halted labor's growth and then, over many

decades, enabled management to roll back labor's previous gains.

First, it ended organizing on the grand, 1930s scale. It outlawed mass picketing, secondary strikes of neutral employers, sit downs: in short, everything [Congress of Industrial Organizations founder John L.] Lewis did in the 1930s.

The second effect of Taft-Hartley was subtler and slower-working. It was to hold up any new organizing at all, even on a quiet, low-key scale. For example, Taft-Hartley ended "card checks." … Taft-Hartley required hearings, campaign periods, secret-ballot elections, and sometimes more hearings, before a union could be officially recognized.

It also allowed and even encouraged employers to threaten workers who want to organize. Employers could hold "captive meetings," bring workers into the office and chew them out for thinking about the Union.

And Taft-Hartley led to the "union-busting" that started in the late 1960s and continues today. It started when a new "profession" of labor consultants began to convince employers that they could violate the [pro-labor 1935] Wagner Act, fire workers at will, fire them deliberately for exercising their legal rights, and nothing would happen. The Wagner Act had never had any real sanctions.

[…]

So why hadn't employers been violating the Wagner Act all along? Well, at first, in the 1930s and 1940s, they tried, and they got riots in the streets: mass picketing, secondary strikes, etc. But after Taft-Hartley, unions couldn't retaliate like this, or they would end up with penalty fines and jail sentences.

In general, scholars debate the influence of politics in determining

union strength in the US and other countries. One argument is that

political parties play an expected role in determining union strength,

with left-wing

governments generally promoting greater union density, while others

contest this finding by pointing out important counterexamples and

explaining the reverse causality inherent in this relationship.

Economic globalization

More

recently, as unions have become increasingly concerned with the impacts

of market integration on their well-being, scholars have begun to

assess whether popular concerns about a global "race to the bottom" are

reflected in cross-country comparisons of union strength. These scholars

use foreign direct investment (FDI) and the size of a country's international trade as a percentage of its GDP to assess a country's relative degree of market integration. These researchers typically find that globalization

does affect union density, but is dependent on other factors, such as

unions' access to the workplace and the centralization of bargaining.

Sano and Williamson argue that globalization's impact is conditional upon a country's labor history.

In the United States in particular, which has traditionally had

relatively low levels of union density, globalization did not appear to

significantly affect union density.

Employer strategies

Illegal union firing [needs explanation] increased during the Reagan administration and has continued since.

Studies focusing more narrowly on the U.S. labor movement corroborate

the comparative findings about the importance of structural factors,

but tend to emphasize the effects of changing labor markets due to

globalization to a greater extent. Bronfenbrenner notes that changes in

the economy, such as increased global competition, capital flight,

and the transitions from a manufacturing to a service economy and to a

greater reliance on transitory and contingent workers, accounts for only

a third of the decline in union density.

Bronfenbrenner claims that the federal government in the 1980s

was largely responsible for giving employers the perception that they

could engage in aggressive strategies to repress the formation of

unions. Richard Freeman also points to the role of repressive employer

strategies in reducing unionization, and highlights the way in which a

state ideology of anti-unionism tacitly accepted these strategies.

Goldfield writes that the overall effects of globalization on

unionization in the particular case of the United States may be

understated in econometric studies on the subject.

He writes that the threat of production shifts reduces unions'

bargaining power even if it does not eliminate them, and also claims

that most of the effects of globalization on labor's strength are

indirect. They are most present in change towards a neoliberal political context that has promoted the deregulation and privatization of some industries and accepted increased employer flexibility in labor markets.

Union responses to globalization

Studies

done by Kate Bronfenbrenner at Cornell University show the adverse

effects of globalization towards unions due to illegal threats of

firing.

Regardless of the actual impact of market integration on union

density or on workers themselves, organized labor has been engaged in a

variety of strategies to limit the agenda of globalization and to

promote labor regulations in an international context. The most

prominent example of this has been the opposition of labor groups to

free trade initiatives such as the North American Free Trade Agreement

(NAFTA) and the Dominican Republic-Central American Free Trade Agreement

(DR-CAFTA). In both cases, unions expressed strong opposition to the

agreements, but to some extent pushed for the incorporation of basic

labor standards in the agreement if one were to pass.

However, Mayer has written that it was precisely unions'

opposition to NAFTA overall that jeopardized organized labor's ability

to influence the debate on labor standards in a significant way.

During Clinton's presidential campaign, labor unions wanted NAFTA to

include a side deal to provide for a kind of international social

charter, a set of standards that would be enforceable both in domestic

courts and through international institutions. Mickey Kantor,

then U.S. trade representative, had strong ties to organized labor and

believed that he could get unions to come along with the agreement,

particularly if they were given a strong voice in the negotiation

process.

When it became clear that Mexico would not stand for this kind of

an agreement, some critics from the labor movement would not settle for

any viable alternatives. In response, part of the labor movement wanted

to declare their open opposition to the agreement, and to push for

NAFTA's rejection in Congress.

Ultimately, the ambivalence of labor groups led those within the

Administration who supported NAFTA to believe that strengthening NAFTA's

labor side agreement too much would cost more votes among Republicans

than it would garner among Democrats, and would make it harder for the

United States to elicit support from Mexico.

Graubart writes that, despite unions' open disappointment with

the outcome of this labor-side negotiation, labor activists, including

the AFL-CIO have used the side agreement's citizen petition process to

highlight ongoing political campaigns and struggles in their home

countries.

He claims that despite the relative weakness of the legal provisions

themselves, the side-agreement has served a legitimizing functioning,

giving certain social struggles a new kind of standing.

Transnational labor regulation

Unions

have recently been engaged in a developing field of transnational labor

regulation embodied in corporate codes of conduct. However, O'Brien

cautions that unions have been only peripherally involved in this

process, and remain ambivalent about its potential effects.

They worry that these codes could have legitimizing effects on

companies that do not actually live up to good practices, and that

companies could use codes to excuse or distract attention from the

repression of unions.

Braun and Gearhart note that although unions do participate in

the structure of a number of these agreements, their original interest

in codes of conduct differed from the interests of human rights and

other non-governmental activists. Unions believed that codes of conduct

would be important first steps in creating written principles that a

company would be compelled to comply with in later organizing contracts,

but did not foresee the establishment of monitoring systems such as the

Fair Labor Association. These authors point out that are motivated by

power, want to gain insider status politically and are accountable to a

constituency that requires them to provide them with direct benefits.

In contrast, activists from the non-governmental sector are

motivated by ideals, are free of accountability and gain legitimacy from

being political outsiders. Therefore, the interests of unions are not

likely to align well with the interests of those who draft and monitor

corporate codes of conduct.

Arguing against the idea that high union wages necessarily make

manufacturing uncompetitive in a globalized economy is labor lawyer Thomas Geoghegan. Busting

unions, in the U.S. manner, as the prime way of competing with China and other countries [does not work]. It's no accident that the social democracies, Sweden, France, and Germany, which kept on paying high wages, now have more industry than the U.S. or the UK. … [T]hat's what the U.S. and the UK did: they smashed the unions, in the belief that they had to compete on cost. The result? They quickly ended up wrecking their industrial base.

Unions have made some attempts to organize across borders. Eder

observes that transnational organizing is not a new phenomenon but has

been facilitated by technological change.

Nevertheless, he claims that while unions pay lip service to global

solidarity, they still act largely in their national self-interest. He

argues that unions in the global North are becoming increasingly

depoliticized while those in the South grow politically, and that global

differentiation of production processes leads to divergent strategies

and interests in different regions of the world. These structural

differences tend to hinder effective global solidarity. However, in

light of the weakness of international labor, Herod writes that

globalization of production need not be met by a globalization of union

strategies in order to be contained. Herod also points out that local

strategies, such as the United Auto Workers' strike against General

Motors in 1998, can sometimes effectively interrupt global production

processes in ways that they could not before the advent of widespread

market integration. Thus, workers need not be connected organizationally

to others around the world to effectively influence the behavior of a

transnational corporation.

Impact

A 2018

study in the Economic History Review found that the rise of labor unions

in the 1930s and 1940s reduced income inequality.