Earthquake

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Global earthquake epicenters, 1963–1998

An earthquake (also known as a quake, tremor or temblor) is the result of a sudden release of energy in the Earth's crust that creates seismic waves. The seismicity, seismism or seismic activity of an area refers to the frequency, type and size of earthquakes experienced over a period of time.

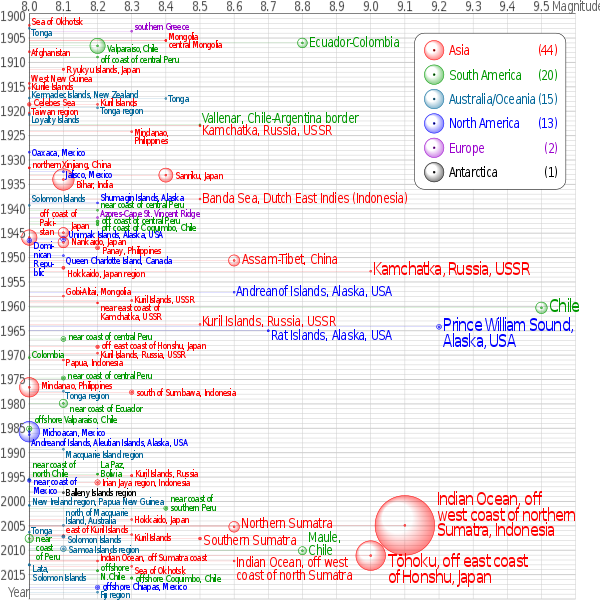

Earthquakes are measured using observations from seismometers. The moment magnitude is the most common scale on which earthquakes larger than approximately 5 are reported for the entire globe. The more numerous earthquakes smaller than magnitude 5 reported by national seismological observatories are measured mostly on the local magnitude scale, also referred to as the Richter scale. These two scales are numerically similar over their range of validity. Magnitude 3 or lower earthquakes are mostly almost imperceptible or weak and magnitude 7 and over potentially cause serious damage over larger areas, depending on their depth. The largest earthquakes in historic times have been of magnitude slightly over 9, although there is no limit to the possible magnitude. The most recent large earthquake of magnitude 9.0 or larger was a 9.0 magnitude earthquake in Japan in 2011 (as of March 2014[update]), and it was the largest Japanese earthquake since records began. Intensity of shaking is measured on the modified Mercalli scale. The shallower an earthquake, the more damage to structures it causes, all else being equal.[1]

At the Earth's surface, earthquakes manifest themselves by shaking and sometimes displacement of the ground. When the epicenter of a large earthquake is located offshore, the seabed may be displaced sufficiently to cause a tsunami. Earthquakes can also trigger landslides, and occasionally volcanic activity.

In its most general sense, the word earthquake is used to describe any seismic event — whether natural or caused by humans — that generates seismic waves. Earthquakes are caused mostly by rupture of geological faults, but also by other events such as volcanic activity, landslides, mine blasts, and nuclear tests. An earthquake's point of initial rupture is called its focus or hypocenter. The epicenter is the point at ground level directly above the hypocenter.

Naturally occurring earthquakes

Tectonic earthquakes occur anywhere in the earth where there is sufficient stored elastic strain energy to drive fracture propagation along a fault plane. The sides of a fault move past each other smoothly and aseismically only if there are no irregularities or asperities along the fault surface that increase the frictional resistance. Most fault surfaces do have such asperities and this leads to a form of stick-slip behaviour. Once the fault has locked, continued relative motion between the plates leads to increasing stress and therefore, stored strain energy in the volume around the fault surface. This continues until the stress has risen sufficiently to break through the asperity, suddenly allowing sliding over the locked portion of the fault, releasing the stored energy. This energy is released as a combination of radiated elastic strain seismic waves, frictional heating of the fault surface, and cracking of the rock, thus causing an earthquake. This process of gradual build-up of strain and stress punctuated by occasional sudden earthquake failure is referred to as the elastic-rebound theory. It is estimated that only 10 percent or less of an earthquake's total energy is radiated as seismic energy.

Most of the earthquake's energy is used to power the earthquake fracture growth or is converted into heat generated by friction. Therefore, earthquakes lower the Earth's available elastic potential energy and raise its temperature, though these changes are negligible compared to the conductive and convective flow of heat out from the Earth's deep interior.[2]

Earthquake fault types

There are three main types of fault, all of which may cause an interplate earthquake: normal, reverse (thrust) and strike-slip. Normal and reverse faulting are examples of dip-slip, where the displacement along the fault is in the direction of dip and movement on them involves a vertical component.Normal faults occur mainly in areas where the crust is being extended such as a divergent boundary.

Reverse faults occur in areas where the crust is being shortened such as at a convergent boundary. Strike-slip faults are steep structures where the two sides of the fault slip horizontally past each other; transform boundaries are a particular type of strike-slip fault. Many earthquakes are caused by movement on faults that have components of both dip-slip and strike-slip; this is known as oblique slip.

Reverse faults, particularly those along convergent plate boundaries are associated with the most powerful earthquakes, megathrust earthquakes, including almost all of those of magnitude 8 or more. Strike-slip faults, particularly continental transforms can produce major earthquakes up to about magnitude 8. Earthquakes associated with normal faults are generally less than magnitude 7.

This is so because the energy released in an earthquake, and thus its magnitude, is proportional to the area of the fault that ruptures[3] and the stress drop. Therefore, the longer the length and the wider the width of the faulted area, the larger the resulting magnitude. The topmost, brittle part of the Earth's crust, and the cool slabs of the tectonic plates that are descending down into the hot mantle, are the only parts of our planet which can store elastic energy and release it in fault ruptures. Rocks hotter than about 300 degrees Celsius flow in response to stress; they do not rupture in earthquakes.[4][5] The maximum observed lengths of ruptures and mapped faults, which may break in one go are approximately 1000 km. Examples are the earthquakes in Chile, 1960; Alaska, 1957; Sumatra, 2004, all in subduction zones. The longest earthquake ruptures on strike-slip faults, like the San Andreas Fault (1857, 1906), the North Anatolian Fault in Turkey (1939) and the Denali Fault in Alaska (2002), are about half to one third as long as the lengths along subducting plate margins, and those along normal faults are even shorter.

Aerial photo of the San Andreas Fault in the Carrizo Plain, northwest of Los Angeles

The most important parameter controlling the maximum earthquake magnitude on a fault is however not the maximum available length, but the available width because the latter varies by a factor of 20.

Along converging plate margins, the dip angle of the rupture plane is very shallow, typically about 10 degrees.[6] Thus the width of the plane within the top brittle crust of the Earth can become 50 to 100 km (Japan, 2011; Alaska, 1964), making the most powerful earthquakes possible.

Strike-slip faults tend to be oriented near vertically, resulting in an approximate width of 10 km within the brittle crust,[7] thus earthquakes with magnitudes much larger than 8 are not possible. Maximum magnitudes along many normal faults are even more limited because many of them are located along spreading centers, as in Iceland, where the thickness of the brittle layer is only about 6 km.[8][9]

In addition, there exists a hierarchy of stress level in the three fault types. Thrust faults are generated by the highest, strike slip by intermediate, and normal faults by the lowest stress levels.[10] This can easily be understood by considering the direction of the greatest principal stress, the direction of the force that 'pushes' the rock mass during the faulting. In the case of normal faults, the rock mass is pushed down in a vertical direction, thus the pushing force (greatest principal stress) equals the weight of the rock mass itself. In the case of thrusting, the rock mass 'escapes' in the direction of the least principal stress, namely upward, lifting the rock mass up, thus the overburden equals the least principal stress. Strike-slip faulting is intermediate between the other two types described above. This difference in stress regime in the three faulting environments can contribute to differences in stress drop during faulting, which contributes to differences in the radiated energy, regardless of fault dimensions.

Earthquakes away from plate boundaries

Where plate boundaries occur within the continental lithosphere, deformation is spread out over a much larger area than the plate boundary itself. In the case of the San Andreas fault continental transform, many earthquakes occur away from the plate boundary and are related to strains developed within the broader zone of deformation caused by major irregularities in the fault trace (e.g., the "Big bend" region). The Northridge earthquake was associated with movement on a blind thrust within such a zone. Another example is the strongly oblique convergent plate boundary between the Arabian and Eurasian plates where it runs through the northwestern part of the Zagros mountains. The deformation associated with this plate boundary is partitioned into nearly pure thrust sense movements perpendicular to the boundary over a wide zone to the southwest and nearly pure strike-slip motion along the Main Recent Fault close to the actual plate boundary itself. This is demonstrated by earthquake focal mechanisms.[11]All tectonic plates have internal stress fields caused by their interactions with neighbouring plates and sedimentary loading or unloading (e.g. deglaciation).[12] These stresses may be sufficient to cause failure along existing fault planes, giving rise to intraplate earthquakes.[13]

Shallow-focus and deep-focus earthquakes

Collapsed Gran Hotel building in the San Salvador metropolis, after the shallow 1986 San Salvador earthquake during mid civil war El Salvador.

Buildings fallen on their foundations after the shallow 1986 San Salvador earthquake, El Salvador.

leveled structures after the shallow 1986 San Salvador earthquake, El Salvador.

The majority of tectonic earthquakes originate at the ring of fire in depths not exceeding tens of kilometers. Earthquakes occurring at a depth of less than 70 km are classified as 'shallow-focus' earthquakes, while those with a focal-depth between 70 and 300 km are commonly termed 'mid-focus' or 'intermediate-depth' earthquakes. In subduction zones, where older and colder oceanic crust descends beneath another tectonic plate, deep-focus earthquakes may occur at much greater depths (ranging from 300 up to 700 kilometers).[14] These seismically active areas of subduction are known as Wadati-Benioff zones. Deep-focus earthquakes occur at a depth where the subducted lithosphere should no longer be brittle, due to the high temperature and pressure. A possible mechanism for the generation of deep-focus earthquakes is faulting caused by olivine undergoing a phase transition into a spinel structure.[15]

Earthquakes and volcanic activity

Earthquakes often occur in volcanic regions and are caused there, both by tectonic faults and the movement of magma in volcanoes. Such earthquakes can serve as an early warning of volcanic eruptions, as during the Mount St. Helens eruption of 1980.[16] Earthquake swarms can serve as markers for the location of the flowing magma throughout the volcanoes. These swarms can be recorded by seismometers and tiltmeters (a device that measures ground slope) and used as sensors to predict imminent or upcoming eruptions.[17]Rupture dynamics

A tectonic earthquake begins by an initial rupture at a point on the fault surface, a process known as nucleation. The scale of the nucleation zone is uncertain, with some evidence, such as the rupture dimensions of the smallest earthquakes, suggesting that it is smaller than 100 m while other evidence, such as a slow component revealed by low-frequency spectra of some earthquakes, suggest that it is larger. The possibility that the nucleation involves some sort of preparation process is supported by the observation that about 40% of earthquakes are preceded by foreshocks. Once the rupture has initiated it begins to propagate along the fault surface. The mechanics of this process are poorly understood, partly because it is difficult to recreate the high sliding velocities in a laboratory. Also the effects of strong ground motion make it very difficult to record information close to a nucleation zone.[18]Rupture propagation is generally modeled using a fracture mechanics approach, likening the rupture to a propagating mixed mode shear crack. The rupture velocity is a function of the fracture energy in the volume around the crack tip, increasing with decreasing fracture energy. The velocity of rupture propagation is orders of magnitude faster than the displacement velocity across the fault. Earthquake ruptures typically propagate at velocities that are in the range 70–90% of the S-wave velocity and this is independent of earthquake size. A small subset of earthquake ruptures appear to have propagated at speeds greater than the S-wave velocity. These supershear earthquakes have all been observed during large strike-slip events. The unusually wide zone of coseismic damage caused by the 2001 Kunlun earthquake has been attributed to the effects of the sonic boom developed in such earthquakes. Some earthquake ruptures travel at unusually low velocities and are referred to as slow earthquakes. A particularly dangerous form of slow earthquake is the tsunami earthquake, observed where the relatively low felt intensities, caused by the slow propagation speed of some great earthquakes, fail to alert the population of the neighbouring coast, as in the 1896 Meiji-Sanriku earthquake.[18]

Tidal forces

Research work has shown a robust correlation between small tidally induced forces and non-volcanic tremor activity.[19][20][21][22]Earthquake clusters

Most earthquakes form part of a sequence, related to each other in terms of location and time.[23]Most earthquake clusters consist of small tremors that cause little to no damage, but there is a theory that earthquakes can recur in a regular pattern.[24]

Aftershocks

An aftershock is an earthquake that occurs after a previous earthquake, the mainshock. An aftershock is in the same region of the main shock but always of a smaller magnitude. If an aftershock is larger than the main shock, the aftershock is redesignated as the main shock and the original main shock is redesignated as a foreshock. Aftershocks are formed as the crust around the displaced fault plane adjusts to the effects of the main shock.[23]Earthquake swarms

Earthquake swarms are sequences of earthquakes striking in a specific area within a short period of time. They are different from earthquakes followed by a series of aftershocks by the fact that no single earthquake in the sequence is obviously the main shock, therefore none have notable higher magnitudes than the other. An example of an earthquake swarm is the 2004 activity at Yellowstone National Park.[25] In August 2012, a swarm of earthquakes shook Southern California's Imperial Valley, showing the most recorded activity in the area since the 1970s.[26]Earthquake storms

Sometimes a series of earthquakes occur in a sort of earthquake storm, where the earthquakes strike a fault in clusters, each triggered by the shaking or stress redistribution of the previous earthquakes.Similar to aftershocks but on adjacent segments of fault, these storms occur over the course of years, and with some of the later earthquakes as damaging as the early ones. Such a pattern was observed in the sequence of about a dozen earthquakes that struck the North Anatolian Fault in Turkey in the 20th century and has been inferred for older anomalous clusters of large earthquakes in the Middle East.[27][28]

Size and frequency of occurrence

It is estimated that around 500,000 earthquakes occur each year, detectable with current instrumentation. About 100,000 of these can be felt.[29][30] Minor earthquakes occur nearly constantly around the world in places like California and Alaska in the U.S., as well as in El Salvador, Mexico, Guatemala, Chile, Peru, Indonesia, Iran, Pakistan, the Azores in Portugal, Turkey, New Zealand, Greece, Italy, India and Japan, but earthquakes can occur almost anywhere, including New York City, London, and Australia.[31] Larger earthquakes occur less frequently, the relationship being exponential; for example, roughly ten times as many earthquakes larger than magnitude 4 occur in a particular time period than earthquakes larger than magnitude 5. In the (low seismicity) United Kingdom, for example, it has been calculated that the average recurrences are: an earthquake of 3.7–4.6 every year, an earthquake of 4.7–5.5 every 10 years, and an earthquake of 5.6 or larger every 100 years.[32] This is an example of the Gutenberg–Richter law.

The Messina earthquake and tsunami took as many as 200,000 lives on December 28, 1908 in Sicily and Calabria.[33]

The number of seismic stations has increased from about 350 in 1931 to many thousands today. As a result, many more earthquakes are reported than in the past, but this is because of the vast improvement in instrumentation, rather than an increase in the number of earthquakes. The United States Geological Survey estimates that, since 1900, there have been an average of 18 major earthquakes (magnitude 7.0–7.9) and one great earthquake (magnitude 8.0 or greater) per year, and that this average has been relatively stable.[34] In recent years, the number of major earthquakes per year has decreased, though this is probably a statistical fluctuation rather than a systematic trend.[35]

More detailed statistics on the size and frequency of earthquakes is available from the United States Geological Survey (USGS).[36] A recent increase in the number of major earthquakes has been noted, which could be explained by a cyclical pattern of periods of intense tectonic activity, interspersed with longer periods of low-intensity. However, accurate recordings of earthquakes only began in the early 1900s, so it is too early to categorically state that this is the case.[37]

Most of the world's earthquakes (90%, and 81% of the largest) take place in the 40,000 km long, horseshoe-shaped zone called the circum-Pacific seismic belt, known as the Pacific Ring of Fire, which for the most part bounds the Pacific Plate.[38][39] Massive earthquakes tend to occur along other plate boundaries, too, such as along the Himalayan Mountains.[40]

With the rapid growth of mega-cities such as Mexico City, Tokyo and Tehran, in areas of high seismic risk, some seismologists are warning that a single quake may claim the lives of up to 3 million people.[41]

Induced seismicity

While most earthquakes are caused by movement of the Earth's tectonic plates, human activity can also produce earthquakes. Four main activities contribute to this phenomenon: storing large amounts of water behind a dam (and possibly building an extremely heavy building), drilling and injecting liquid into wells, and by coal mining and oil drilling.[42] Perhaps the best known example is the 2008 Sichuan earthquake in China's Sichuan Province in May; this tremor resulted in 69,227 fatalities and is the 19th deadliest earthquake of all time. The Zipingpu Dam is believed to have fluctuated the pressure of the fault 1,650 feet (503 m) away; this pressure probably increased the power of the earthquake and accelerated the rate of movement for the fault.[43] The greatest earthquake in Australia's history is also claimed to be induced by humanity, through coal mining. The city of Newcastle was built over a large sector of coal mining areas. The earthquake has been reported to be spawned from a fault that reactivated due to the millions of tonnes of rock removed in the mining process.[44]Measuring and locating earthquakes

Earthquakes can be recorded by seismometers up to great distances, because seismic waves travel through the whole Earth's interior. The absolute magnitude of a quake is conventionally reported by numbers on the moment magnitude scale (formerly Richter scale, magnitude 7 causing serious damage over large areas), whereas the felt magnitude is reported using the modified Mercalli intensity scale (intensity II–XII).Every tremor produces different types of seismic waves, which travel through rock with different velocities:

- Longitudinal P-waves (shock- or pressure waves)

- Transverse S-waves (both body waves)

- Surface waves — (Rayleigh and Love waves)

In solid rock P-waves travel at about 6 to 7 km per second; the velocity increases within the deep mantle to ~13 km/s. The velocity of S-waves ranges from 2–3 km/s in light sediments and 4–5 km/s in the Earth's crust up to 7 km/s in the deep mantle. As a consequence, the first waves of a distant earthquake arrive at an observatory via the Earth's mantle.

On average, the kilometer distance to the earthquake is the number of seconds between the P and S wave times 8.[45] Slight deviations are caused by inhomogeneities of subsurface structure. By such analyses of seismograms the Earth's core was located in 1913 by Beno Gutenberg.

Earthquakes are not only categorized by their magnitude but also by the place where they occur. The world is divided into 754 Flinn–Engdahl regions (F-E regions), which are based on political and geographical boundaries as well as seismic activity. More active zones are divided into smaller F-E regions whereas less active zones belong to larger F-E regions.

Standard reporting of earthquakes includes its magnitude, date and time of occurrence, geographic coordinates of its epicenter, depth of the epicenter, geographical region, distances to population centers, location uncertainty, a number of parameters that are included in USGS earthquake reports (number of stations reporting, number of observations, etc.), and a unique event ID.[46]

Effects of earthquakes

1755 copper engraving depicting Lisbon in ruins and in flames after the 1755 Lisbon earthquake, which killed an estimated 60,000 people. A tsunami overwhelms the ships in the harbor.

The effects of earthquakes include, but are not limited to, the following:

Shaking and ground rupture

Shaking and ground rupture are the main effects created by earthquakes, principally resulting in more or less severe damage to buildings and other rigid structures. The severity of the local effects depends on the complex combination of the earthquake magnitude, the distance from the epicenter, and the local geological and geomorphological conditions, which may amplify or reduce wave propagation.[47] The ground-shaking is measured by ground acceleration.

Specific local geological, geomorphological, and geostructural features can induce high levels of shaking on the ground surface even from low-intensity earthquakes. This effect is called site or local amplification. It is principally due to the transfer of the seismic motion from hard deep soils to soft superficial soils and to effects of seismic energy focalization owing to typical geometrical setting of the deposits.

Ground rupture is a visible breaking and displacement of the Earth's surface along the trace of the fault, which may be of the order of several metres in the case of major earthquakes. Ground rupture is a major risk for large engineering structures such as dams, bridges and nuclear power stations and requires careful mapping of existing faults to identify any which are likely to break the ground surface within the life of the structure.[48]

Landslides and avalanches

Landslides became a symbol of the devastation the 2001 El Salvador earthquakes left, killing hundreds in its wake.

Fires

Fires of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake

Earthquakes can cause fires by damaging electrical power or gas lines. In the event of water mains rupturing and a loss of pressure, it may also become difficult to stop the spread of a fire once it has started. For example, more deaths in the 1906 San Francisco earthquake were caused by fire than by the earthquake itself.[50]

Soil liquefaction

Soil liquefaction occurs when, because of the shaking, water-saturated granular material (such as sand) temporarily loses its strength and transforms from a solid to a liquid. Soil liquefaction may cause rigid structures, like buildings and bridges, to tilt or sink into the liquefied deposits. For example, in the 1964 Alaska earthquake, soil liquefaction caused many buildings to sink into the ground, eventually collapsing upon themselves.[51]Tsunami

The tsunami of the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake

A large ferry boat rests inland amidst destroyed houses after a 9.0 earthquake and subsequent tsunami struck Japan in March 2011.

Tsunamis are long-wavelength, long-period sea waves produced by the sudden or abrupt movement of large volumes of water. In the open ocean the distance between wave crests can surpass 100 kilometers (62 mi), and the wave periods can vary from five minutes to one hour. Such tsunamis travel 600-800 kilometers per hour (373–497 miles per hour), depending on water depth. Large waves produced by an earthquake or a submarine landslide can overrun nearby coastal areas in a matter of minutes. Tsunamis can also travel thousands of kilometers across open ocean and wreak destruction on far shores hours after the earthquake that generated them.[52]

Ordinarily, subduction earthquakes under magnitude 7.5 on the Richter scale do not cause tsunamis, although some instances of this have been recorded. Most destructive tsunamis are caused by earthquakes of magnitude 7.5 or more.[52]

Floods

A flood is an overflow of any amount of water that reaches land.[53] Floods occur usually when the volume of water within a body of water, such as a river or lake, exceeds the total capacity of the formation, and as a result some of the water flows or sits outside of the normal perimeter of the body.However, floods may be secondary effects of earthquakes, if dams are damaged. Earthquakes may cause landslips to dam rivers, which collapse and cause floods.[54]

The terrain below the Sarez Lake in Tajikistan is in danger of catastrophic flood if the landslide dam formed by the earthquake, known as the Usoi Dam, were to fail during a future earthquake. Impact projections suggest the flood could affect roughly 5 million people.[55]

Human impacts

An earthquake may cause injury and loss of life, road and bridge damage, general property damage, and collapse or destabilization (potentially leading to future collapse) of buildings. The aftermath may bring disease, lack of basic necessities, and higher insurance premiums.Major earthquakes

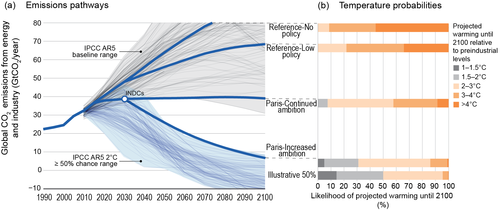

Earthquakes of magnitude 8.0 and greater since 1900. The apparent 3D volumes of the bubbles are linearly proportional to their respective fatalities.[56]

One of the most devastating earthquakes in recorded history was the 1556 Shaanxi earthquake, which occurred on 23 January 1556 in Shaanxi province, China. More than 830,000 people died.[57] Most houses in the area were yaodongs—dwellings carved out of loess hillsides—and many victims were killed when these structures collapsed. The 1976 Tangshan earthquake, which killed between 240,000 to 655,000 people, was the deadliest of the 20th century.[58]

The 1960 Chilean Earthquake is the largest earthquake that has been measured on a seismograph, reaching 9.5 magnitude on 22 May 1960.[29][30] Its epicenter was near Cañete, Chile. The energy released was approximately twice that of the next most powerful earthquake, the Good Friday Earthquake, which was centered in Prince William Sound, Alaska.[59][60] The ten largest recorded earthquakes have all been megathrust earthquakes; however, of these ten, only the 2004 Indian Ocean earthquake is simultaneously one of the deadliest earthquakes in history.

Earthquakes that caused the greatest loss of life, while powerful, were deadly because of their proximity to either heavily populated areas or the ocean, where earthquakes often create tsunamis that can devastate communities thousands of kilometers away. Regions most at risk for great loss of life include those where earthquakes are relatively rare but powerful, and poor regions with lax, unenforced, or nonexistent seismic building codes.

Prediction

Many methods have been developed for predicting the time and place in which earthquakes will occur. Despite considerable research efforts by seismologists, scientifically reproducible predictions cannot yet be made to a specific day or month.[61] However, for well-understood faults the probability that a segment may rupture during the next few decades can be estimated.[62]Earthquake warning systems have been developed that can provide regional notification of an earthquake in progress, but before the ground surface has begun to move, potentially allowing people within the system's range to seek shelter before the earthquake's impact is felt.

Preparedness

The objective of earthquake engineering is to foresee the impact of earthquakes on buildings and other structures and to design such structures to minimize the risk of damage. Existing structures can be modified by seismic retrofitting to improve their resistance to earthquakes. Earthquake insurance can provide building owners with financial protection against losses resulting from earthquakes.Emergency management strategies can be employed by a government or organization to mitigate risks and prepare for consequences.

Historical views

From the lifetime of the Greek philosopher Anaxagoras in the 5th century BCE to the 14th century CE, earthquakes were usually attributed to "air (vapors) in the cavities of the Earth."[63] Thales of Miletus, who lived from 625–547 (BCE) was the only documented person who believed that earthquakes were caused by tension between the earth and water.[63] Other theories existed, including the Greek philosopher Anaxamines' (585–526 BCE) beliefs that short incline episodes of dryness and wetness caused seismic activity. The Greek philosopher Democritus (460–371 BCE) blamed water in general for earthquakes.[63] Pliny the Elder called earthquakes "underground thunderstorms."[63]Earthquakes in culture

Mythology and religion

In Norse mythology, earthquakes were explained as the violent struggling of the god Loki. When Loki, god of mischief and strife, murdered Baldr, god of beauty and light, he was punished by being bound in a cave with a poisonous serpent placed above his head dripping venom. Loki's wife Sigyn stood by him with a bowl to catch the poison, but whenever she had to empty the bowl the poison dripped on Loki's face, forcing him to jerk his head away and thrash against his bonds, which caused the earth to tremble.[64]In Greek mythology, Poseidon was the cause and god of earthquakes. When he was in a bad mood, he struck the ground with a trident, causing earthquakes and other calamities. He also used earthquakes to punish and inflict fear upon people as revenge.[citation needed]

In Japanese mythology, Namazu (鯰) is a giant catfish who causes earthquakes. Namazu lives in the mud beneath the earth, and is guarded by the god Kashima who restrains the fish with a stone. When Kashima lets his guard fall, Namazu thrashes about, causing violent earthquakes.

Popular culture

In modern popular culture, the portrayal of earthquakes is shaped by the memory of great cities laid waste, such as Kobe in 1995 or San Francisco in 1906.[65] Fictional earthquakes tend to strike suddenly and without warning.[65] For this reason, stories about earthquakes generally begin with the disaster and focus on its immediate aftermath, as in Short Walk to Daylight (1972), The Ragged Edge (1968) or Aftershock: Earthquake in New York (1998).[65] A notable example is Heinrich von Kleist's classic novella, The Earthquake in Chile, which describes the destruction of Santiago in 1647. Haruki Murakami's short fiction collection After the Quake depicts the consequences of the Kobe earthquake of 1995.The most popular single earthquake in fiction is the hypothetical "Big One" expected of California's San Andreas Fault someday, as depicted in the novels Richter 10 (1996) and Goodbye California (1977) among other works.[65] Jacob M. Appel's widely anthologized short story, A Comparative Seismology, features a con artist who convinces an elderly woman that an apocalyptic earthquake is imminent.[66]

Contemporary depictions of earthquakes in film are variable in the manner in which they reflect human psychological reactions to the actual trauma that can be caused to directly afflicted families and their loved ones.[67] Disaster mental health response research emphasizes the need to be aware of the different roles of loss of family and key community members, loss of home and familiar surroundings, loss of essential supplies and services to maintain survival.[68][69] Particularly for children, the clear availability of caregiving adults who are able to protect, nourish, and clothe them in the aftermath of the earthquake, and to help them make sense of what has befallen them has been shown even more important to their emotional and physical health than the simple giving of provisions.[70] As was observed after other disasters involving destruction and loss of life and their media depictions, such as those of the 2001 World Trade Center Attacks or Hurricane Katrina—and has been recently observed in the 2010 Haiti earthquake, it is also important not to pathologize the reactions to loss and displacement or disruption of governmental administration and services, but rather to validate these reactions, to support constructive problem-solving and reflection as to how one might improve the conditions of those affected.[71]