From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

"The Knight's Dream", 1655, by Antonio de Pereda

Dreams are successions of images, ideas, emotions, and sensations that occur involuntarily in the mind during certain stages of sleep.[1] The content and purpose of dreams are not definitively understood, though they have been a topic of scientific speculation, as well as a subject of philosophical and religious interest, throughout recorded history. The scientific study of dreams is called oneirology.[2]

Dreams mainly occur in the rapid-eye movement (REM) stage of sleep—when brain activity is high and resembles that of being awake. REM sleep is revealed by continuous movements of the eyes during sleep. At times, dreams may occur during other stages of sleep. However, these dreams tend to be much less vivid or memorable.[3]

The length of a dream can vary; they may last for a few seconds, or approximately 20–30 minutes.[3] People are more likely to remember the dream if they are awakened during the REM phase. The average person has three to five dreams per night, but some may have up to seven dreams in one night.[4] The dreams tend to last longer as the night progresses. During a full eight-hour night sleep, most dreams occur in the typical two hours of REM.[5]

In modern times, dreams have been seen as a connection to the unconscious mind. They range from normal and ordinary to overly surreal and bizarre. Dreams can have varying natures, such as frightening, exciting, magical, melancholic, adventurous, or sexual. The events in dreams are generally outside the control of the dreamer, with the exception of lucid dreaming, where the dreamer is self-aware.[6] Dreams can at times make a creative thought occur to the person or give a sense of inspiration.[7]

Opinions about the meaning of dreams have varied and shifted through time and culture. The earliest recorded dreams were acquired from materials dating back approximately 5000 years, in Mesopotamia, where they were documented on clay tablets. In the Greek and Roman periods, the people believed that dreams were direct messages from one and/or multiple deities, from deceased persons, and that they predicted the future. Some cultures practiced dream incubation with the intention of cultivating dreams that are of prophecy.[8]

Sigmund Freud, who developed the discipline of psychoanalysis, wrote extensively about dream theories and their interpretations in the early 1900s.[9] He explained dreams as manifestations of our deepest desires and anxieties, often relating to repressed childhood memories or obsessions. In The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), Freud developed a psychological technique to interpret dreams and devised a series of guidelines to understand the symbols and motifs that appear in our dreams.

Cultural meaning

Ancient history

The Dreaming is a common term within the animist creation narrative of indigenous Australians for a personal, or group, creation and for what may be understood as the "timeless time" of formative creation and perpetual creating.[10]The Sumerians in Mesopotamia left evidence of dreams dating back to 3100 BC. According to these early recorded stories, gods and kings, like the 7th century BC scholar-king Assurbanipal, paid close attention to dreams. In his archive of clay tablets, some accounts of the story of the legendary king Gilgamesh were found.[11]

The Mesopotamians believed that the soul, or some part of it, moves out from the body of the sleeping person and actually visits the places and persons the dreamer sees in their sleep. Sometimes the god of dreams is said to carry the dreamer.[12] Babylonians and Assyrians divided dreams into "good," which were sent by the gods, and "bad," sent by demons - They also believed that their dreams were omens and prophecies.[13]

In ancient Egypt, as far back as 2000 BC, the Egyptians wrote down their dreams on papyrus. People with vivid and significant dreams were thought blessed and were considered special.[14] Ancient Egyptians believed that dreams were like oracles, bringing messages from the gods. They thought that the best way to receive divine revelation was through dreaming and thus they would induce (or "incubate") dreams. Egyptians would go to sanctuaries and sleep on special "dream beds" in hope of receiving advice, comfort, or healing from the gods.[15]

Classical history

In Chinese history, people wrote of two vital aspects of the soul of which one is freed from the body during slumber to journey in a dream realm, while the other remained in the body,[16] although this belief and dream interpretation had been questioned since early times, such as by the philosopher Wang Chong (27-97).[16] The Indian text Upanishads, written between 900 and 500 BC, emphasize two meanings of dreams. The first says that dreams are merely expressions of inner desires. The second is the belief of the soul leaving the body and being guided until awakened.

The Greeks shared their beliefs with the Egyptians on how to interpret good and bad dreams, and the idea of incubating dreams. Morpheus, the Greek god of dreams, also sent warnings and prophecies to those who slept at shrines and temples. The earliest Greek beliefs about dreams were that their gods physically visited the dreamers, where they entered through a keyhole, exiting the same way after the divine message was given.

Antiphon wrote the first known Greek book on dreams in the 5th century BC. In that century, other cultures influenced Greeks to develop the belief that souls left the sleeping body.[17] Hippocrates (469-399 BC) had a simple dream theory: during the day, the soul receives images; during the night, it produces images. Greek philosopher Aristotle (384-322 BC) believed dreams caused physiological activity. He thought dreams could analyze illness and predict diseases. Marcus Tullius Cicero, for his part, believed that all dreams are produced by thoughts and conversations a dreamer had during the preceding days.[18] Cicero's Somnium Scipionis described a lengthy dream vision, which in turn was commented on by Macrobius in his Commentarii in Somnium Scipionis.

In Abrahamic religions

In Judaism, dreams are considered part of the experience of the world that can be interpreted and from which lessons can be garnered. It is discussed in the Talmud, Tractate Berachot 55-60.

The ancient Hebrews connected their dreams heavily with their religion, though the Hebrews were monotheistic and believed that dreams were the voice of one God alone. Hebrews also differentiated between good dreams (from God) and bad dreams (from evil spirits). The Hebrews, like many other ancient cultures, incubated dreams in order to receive divine revelation. For example, the Hebrew prophet Samuel would "lie down and sleep in the temple at Shiloh before the Ark and receive the word of the Lord." Most of the dreams in the Bible are in the Book of Genesis.[19]

Christians mostly shared their beliefs with the Hebrews and thought that dreams were of a supernatural character because the Old Testament includes frequent stories of dreams with divine inspiration. The most famous of these dream stories was Jacob's dream of a ladder that stretches from Earth to Heaven. Many Christians preach that God can speak to people through their dreams.

Iain R. Edgar has researched the role of dreams in Islam.[20] He has argued that dreams play an important role in the history of Islam and the lives of Muslims, since dream interpretation is the only way that Muslims can receive revelations from God since the death of the last Prophet Mohammed.[21]

Dreams and philosophical realism

Some philosophers have concluded that what we think of as the "real world" could be or is an illusion (an idea known as the skeptical hypothesis about ontology).The first recorded mention of the idea was by Zhuangzi, and it is also discussed in Hinduism, which makes extensive use of the argument in its writings.[22] It was formally introduced to Western philosophy by Descartes in the 17th century in his Meditations on First Philosophy. Stimulus, usually an auditory one, becomes a part of a dream, eventually then awakening the dreamer.

Postclassical and medieval history

Some Indigenous American tribes and Mexican civilizations believe that dreams are a way of visiting and having contact with their ancestors.[23] Some Native American tribes used vision quests as a rite of passage, fasting and praying until an anticipated guiding dream was received, to be shared with the rest of the tribe upon their return.[24][25]The Middle Ages brought a harsh interpretation of dreams. They were seen as evil, and the images as temptations from the devil. Many believed that during sleep, the devil could fill the human mind with corrupting and harmful thoughts. Martin Luther, founder of Protestantism, believed dreams were the work of the Devil. However, Catholics such as St. Augustine and St. Jerome claimed that the direction of their lives was heavily influenced by their dreams.

In art

Dreams and dark imaginings are the theme of Goya's etching The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters. Salvador Dalí's Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening (1944) also investigates this theme through absurd juxtapositions of a nude lady, tigers leaping out of a pomegranate, and a spider-like elephant walking in the background. Henri Rousseau's last painting was The Dream. Le Rêve ("The Dream") is a 1932 painting by Pablo Picasso.In literature

Dream frames were frequently used in medieval allegory to justify the narrative; The Book of the Duchess[26] and The Vision Concerning Piers Plowman[27] are two such dream visions. Even before them, in antiquity, the same device had been used by Cicero and Lucian of Samosata.They have also featured in fantasy and speculative fiction since the 19th century. One of the best-known dream worlds is Wonderland from Lewis Carroll's Alice's Adventures in Wonderland, as well as Looking-Glass Land from its sequel, Through the Looking-Glass. Unlike many dream worlds, Carroll's logic is like that of actual dreams, with transitions and flexible causality.

Other fictional dream worlds include the Dreamlands of H. P. Lovecraft's Dream Cycle[28] and The Neverending Story 's[29] world of Fantasia, which includes places like the Desert of Lost Dreams, the Sea of Possibilities and the Swamps of Sadness. Dreamworlds, shared hallucinations and other alternate realities feature in a number of works by Phillip K. Dick, such as The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch and Ubik. Similar themes were explored by Jorge Luis Borges, for instance in The Circular Ruins.

In popular culture

Modern popular culture often conceives of dreams, like Freud, as expressions of the dreamer's deepest fears and desires.[30] The film version of The Wizard of Oz (1939) depicts a full-color dream that causes Dorothy to perceive her black-and-white reality and those with whom she shares it in a new way. In films such as Spellbound (1945), The Manchurian Candidate (1962), Field of Dreams (1989), and Inception (2010), the protagonists must extract vital clues from surreal dreams.[31]Most dreams in popular culture are, however, not symbolic, but straightforward and realistic depictions of their dreamer's fears and desires.[31] Dream scenes may be indistinguishable from those set in the dreamer's real world, a narrative device that undermines the dreamer's and the audience's sense of security[31] and allows horror film protagonists, such as those of Carrie (1976), Friday the 13th (1980) or An American Werewolf in London (1981) to be suddenly attacked by dark forces while resting in seemingly safe places.[31]

In speculative fiction, the line between dreams and reality may be blurred even more in the service of the story.[31] Dreams may be psychically invaded or manipulated (Dreamscape, 1984; the Nightmare on Elm Street films, 1984–2010; Inception, 2010) or even come literally true (as in The Lathe of Heaven, 1971). In Ursula K. Le Guin's book, The Lathe of Heaven (1971), the protagonist finds that his "effective" dreams can retroactively change reality. Peter Weir's 1977 Australian film The Last Wave makes a simple and straightforward postulate about the premonitory nature of dreams (from one of his Aboriginal characters) that "... dreams are the shadow of something real". In Kyell Gold's novel Green Fairy from the Dangerous Spirits series, the protagonist, Sol, experiences the memories of a dancer who died 100 years before through Absinthe induced dreams and after each dream something from it materializes into his reality. Such stories play to audiences' experiences with their own dreams, which feel as real to them.[31]

Dynamic psychiatry

Freudian view of dreams

In the late 19th century, psychotherapist Sigmund Freud developed a theory that the content of dreams is driven by unconscious wish fulfillment. Freud called dreams the "royal road to the unconscious."[32] He theorized that the content of dreams reflects the dreamer's unconscious mind and specifically that dream content is shaped by unconscious wish fulfillment. He argued that important unconscious desires often relate to early childhood memories and experiences. Freud's theory describes dreams as having both manifest and latent content. Latent content relates to deep unconscious wishes or fantasies while manifest content is superficial and meaningless. Manifest content often masks or obscures latent content.In his early work, Freud argued that the vast majority of latent dream content is sexual in nature, but he later moved away from this categorical position. In Beyond the Pleasure Principle he considered how trauma or aggression could influence dream content. He also discussed supernatural origins in Dreams and Occultism, a lecture published in New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis.[33]

Jungian and other views of dreams

Carl Jung rejected many of Freud's theories. Jung expanded on Freud's idea that dream content relates to the dreamer's unconscious desires. He described dreams as messages to the dreamer and argued that dreamers should pay attention for their own good. He came to believe that dreams present the dreamer with revelations that can uncover and help to resolve emotional or religious problems and fears.[34]Jung wrote that recurring dreams show up repeatedly to demand attention, suggesting that the dreamer is neglecting an issue related to the dream. He believed that many of the symbols or images from these dreams return with each dream. Jung believed that memories formed throughout the day also play a role in dreaming. These memories leave impressions for the unconscious to deal with when the ego is at rest. The unconscious mind re-enacts these glimpses of the past in the form of a dream. Jung called this a day residue.[35] Jung also argued that dreaming is not a purely individual concern, that all dreams are part of "one great web of psychological factors."

Fritz Perls presented his theory of dreams as part of the holistic nature of Gestalt therapy. Dreams are seen as projections of parts of the self that have been ignored, rejected, or suppressed.[36] Jung argued that one could consider every person in the dream to represent an aspect of the dreamer, which he called the subjective approach to dreams. Perls expanded this point of view to say that even inanimate objects in the dream may represent aspects of the dreamer. The dreamer may, therefore, be asked to imagine being an object in the dream and to describe it, in order to bring into awareness the characteristics of the object that correspond with the dreamer's personality.

The neurobiology of dreaming

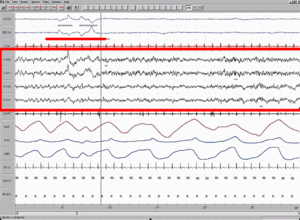

EEG showing brainwaves during REM sleep

Accumulated observation has shown that dreams are strongly associated with REM rapid eye movement sleep, during which an electroencephalogram (EEG) shows brain activity that, among sleep states, is most like wakefulness. Participant-remembered dreams during NREM sleep are normally more mundane in comparison.[37] During a typical lifespan, a person spends a total of about six years dreaming[38] (which is about two hours each night).[39] Most dreams only last 5 to 20 minutes.[38] It is unknown where in the brain dreams originate, if there is a single origin for dreams or if multiple portions of the brain are involved, or what the purpose of dreaming is for the body or mind.

During REM sleep, the release of the neurotransmitters norepinephrine, serotonin and histamine is completely suppressed.[40][41][42]

During most dreams, the person dreaming is not aware that they are dreaming, no matter how absurd or eccentric the dream is. The reason for this may be that the prefrontal cortex, the region of the brain responsible for logic and planning, exhibits decreased activity during dreams. This allows the dreamer to more actively interact with the dream without thinking about what might happen, since things that would normally stand out in reality blend in with the dream scenery.[43]

When REM sleep episodes were timed for their duration and subjects were awakened to make reports before major editing or forgetting of their dreams could take place, subjects accurately reported the length of time they had been dreaming in an REM sleep state. Some researchers have speculated that "time dilation" effects only seem to be taking place upon reflection and do not truly occur within dreams.[44] This close correlation of REM sleep and dream experience was the basis of the first series of reports describing the nature of dreaming: that it is a regular nightly rather than occasional phenomenon, and is correlated with high-frequency activity within each sleep period occurring at predictable intervals of approximately every 60–90 minutes in all humans throughout the lifespan.

REM sleep episodes and the dreams that accompany them lengthen progressively through the night, with the first episode being shortest, of approximately 10–12 minutes duration, and the second and third episodes increasing to 15–20 minutes. Dreams at the end of the night may last as long as 15 minutes, although these may be experienced as several distinct episodes due to momentary arousals interrupting sleep as the night ends. Dream reports can be reported from normal subjects 50% of the time when they are awakened prior to the end of the first REM period. This rate of retrieval is increased to about 99% when awakenings are made from the last REM period of the night. The increase in the ability to recall dreams appears related to intensification across the night in the vividness of dream imagery, colors, and emotions.[45]

Dreams in animals

REM sleep and the ability to dream seem to be embedded in the biology of many animals in addition to humans. Scientific research suggests that all mammals experience REM.[46] The range of REM can be seen across species: dolphins experience minimal REM, while humans are in the middle of the scale and the armadillo and the opossum (a marsupial) are among the most prolific dreamers, judging from their REM patterns.[47]Studies have observed dreaming in mammals such as monkeys, dogs, cats, rats, elephants, and shrews. There have also been signs of dreaming in birds and reptiles.[48] Sleeping and dreaming are intertwined. Scientific research results regarding the function of dreaming in animals remain disputable; however, the function of sleeping in living organisms is increasingly clear. For example, recent sleep deprivation experiments conducted on rats and other animals have resulted in the deterioration of physiological functioning and actual tissue damage.[49]

Some scientists argue that humans dream for the same reason other amniotes do. From a Darwinian perspective dreams would have to fulfill some kind of biological requirement, provide some benefit for natural selection to take place, or at least have no negative impact on fitness. In 2000 Antti Revonsuo, a professor at the University of Turku in Finland, claimed that centuries ago dreams would prepare humans for recognizing and avoiding danger by presenting a simulation of threatening events. The theory has therefore been called the threat-simulation theory.[50] According to Tsoukalas (2012) dreaming is related to the reactive patterns elicited by encounters with predators, a fact that is still evident in the control mechanisms of REM sleep (see below).[51][52]

Neurological theories of dreams

Activation synthesis theory

In 1976 J. Allan Hobson and Robert McCarley proposed a new theory that changed dream research, challenging the previously held Freudian view of dreams as unconscious wishes to be interpreted. They assume that the same structures that induce REM sleep also generate sensory information. Hobson's 1976 research suggested that the signals interpreted as dreams originate in the brainstem during REM sleep. According to Hobson and other researchers, circuits in the brainstem are activated during REM sleep. Once these circuits are activated, areas of the limbic system involved in emotions, sensations, and memories, including the amygdala and hippocampus, become active. The brain synthesizes and interprets these activities; for example, changes in the physical environment such as temperature and humidity, or physical stimuli such as ejaculation, and attempts to create meaning from these signals, result in dreaming.However, research by Mark Solms suggests that dreams are generated in the forebrain, and that REM sleep and dreaming are not directly related.[53] While working in the neurosurgery department at hospitals in Johannesburg and London, Solms had access to patients with various brain injuries. He began to question patients about their dreams and confirmed that patients with damage to the parietal lobe stopped dreaming; this finding was in line with Hobson's 1977 theory. However, Solms did not encounter cases of loss of dreaming with patients having brainstem damage. This observation forced him to question Hobson's prevailing theory, which marked the brainstem as the source of the signals interpreted as dreams.

Continual-activation theory

Combining Hobson's activation synthesis hypothesis with Solms' findings, the continual-activation theory of dreaming presented by Jie Zhang proposes that dreaming is a result of brain activation and synthesis; at the same time, dreaming and REM sleep are controlled by different brain mechanisms.Zhang hypothesizes that the function of sleep is to process, encode, and transfer the data from the temporary memory store to the long-term memory store. During NREM sleep the conscious-related memory (declarative memory) is processed, and during REM sleep the unconscious related memory (procedural memory) is processed.[citation needed]

Zhang assumes that during REM sleep the unconscious part of a brain is busy processing the procedural memory; meanwhile, the level of activation in the conscious part of the brain descends to a very low level as the inputs from the sensory systems are basically disconnected. This triggers the "continual-activation" mechanism to generate a data stream from the memory stores to flow through the conscious part of the brain. Zhang suggests that this pulse-like brain activation is the inducer of each dream. He proposes that, with the involvement of the brain associative thinking system, dreaming is, thereafter, self-maintained with the dreamer's own thinking until the next pulse of memory insertion. This explains why dreams have both characteristics of continuity (within a dream) and sudden changes (between two dreams).[54][55]

Defensive immobilization: the precursor of dreams

According to Tsoukalas (2012) REM sleep is an evolutionary transformation of a well-known defensive mechanism, the tonic immobility reflex. This reflex, also known as animal hypnosis or death feigning, functions as the last line of defense against an attacking predator and consists of the total immobilization of the animal: the animal appears dead (cf. "playing possum"). Tsoukalas claims that the neurophysiology and phenomenology of this reaction shows striking similarities to REM sleep, a fact that suggests a deep evolutionary kinship. For example, both reactions exhibit brainstem control, paralysis, sympathetic activation, and thermoregulatory changes. Tsoukalas claims that this theory integrates many earlier findings into a unified framework.[51][52]Dreams as excitations of long-term memory

Eugen Tarnow suggests that dreams are ever-present excitations of long-term memory, even during waking life. The strangeness of dreams is due to the format of long-term memory, reminiscent of Penfield & Rasmussen's findings that electrical excitations of the cortex give rise to experiences similar to dreams. During waking life an executive function interprets long-term memory consistent with reality checking. Tarnow's theory is a reworking of Freud's theory of dreams in which Freud's unconscious is replaced with the long-term memory system and Freud's "Dream Work" describes the structure of long-term memory.[56]Dreams for strengthening of semantic memories

A 2001 study showed evidence that illogical locations, characters, and dream flow may help the brain strengthen the linking and consolidation of semantic memories.[57] These conditions may occur because, during REM sleep, the flow of information between the hippocampus and neocortex is reduced.[58]

Increasing levels of the stress hormone cortisol late in sleep (often during REM sleep) causes this decreased communication. One stage of memory consolidation is the linking of distant but related memories. Payne and Nadal hypothesize these memories are then consolidated into a smooth narrative, similar to a process that happens when memories are created under stress.[59] Robert (1886),[60] a physician from Hamburg, was the first who suggested that dreams are a need and that they have the function to erase (a) sensory impressions that were not fully worked up, and (b) ideas that were not fully developed during the day. By the dream work, incomplete material is either removed (suppressed) or deepened and included into memory. Robert's ideas were cited repeatedly by Freud in his Die Traumdeutung. Hughlings Jackson (1911) viewed that sleep serves to sweep away unnecessary memories and connections from the day.

This was revised in 1983 by Crick and Mitchison's "reverse learning" theory, which states that dreams are like the cleaning-up operations of computers when they are off-line, removing (suppressing) parasitic nodes and other "junk" from the mind during sleep.[61][62] However, the opposite view that dreaming has an information handling, memory-consolidating function (Hennevin and Leconte, 1971) is also common.

Psychological theories of dreams

Dreams for testing and selecting mental schemas

Coutts[63] describes dreams as playing a central role in a two-phase sleep process that improves the mind's ability to meet human needs during wakefulness. During the accommodation phase, mental schemas self-modify by incorporating dream themes. During the emotional selection phase, dreams test prior schema accommodations. Those that appear adaptive are retained, while those that appear maladaptive are culled. The cycle maps to the sleep cycle, repeating several times during a typical night's sleep. Alfred Adler suggested that dreams are often emotional preparations for solving problems, intoxicating an individual away from common sense toward private logic. The residual dream feelings may either reinforce or inhibit contemplated action.Evolutionary psychology theories of dreams

Numerous theories state that dreaming is a random by-product of REM sleep physiology and that it does not serve any natural purpose.[64] Flanagan claims that "dreams are evolutionary epiphenomena" and they have no adaptive function. "Dreaming came along as a free ride on a system designed to think and to sleep."[65] Hobson, for different reasons, also considers dreams epiphenomena. He believes that the substance of dreams have no significant influence on waking actions, and most people go about their daily lives perfectly well without remembering their dreams.[66]Hobson proposed the activation-synthesis theory, which states that "there is a randomness of dream imagery and the randomness synthesizes dream-generated images to fit the patterns of internally generated stimulations".[67] This theory is based on the physiology of REM sleep, and Hobson believes dreams are the outcome of the forebrain reacting to random activity beginning at the brainstem. The activation-synthesis theory hypothesizes that the peculiar nature of dreams is attributed to certain parts of the brain trying to piece together a story out of what is essentially bizarre information.[68]

However, evolutionary psychologists believe dreams serve some adaptive function for survival. Deirdre Barrett describes dreaming as simply "thinking in different biochemical state" and believes people continue to work on all the same problems—personal and objective—in that state.[69] Her research finds that anything—math, musical composition, business dilemmas—may get solved during dreaming.[70][71] In a related theory, which Mark Blechner terms "Oneiric Darwinism," dreams are seen as creating new ideas through the generation of random thought mutations. Some of these may be rejected by the mind as useless, while others may be seen as valuable and retained.[72]

Finnish psychologist Antti Revonsuo posits that dreams have evolved for "threat simulation" exclusively. According to the Threat Simulation Theory he proposes, during much of human evolution physical and interpersonal threats were serious, giving reproductive advantage to those who survived them. Therefore dreaming evolved to replicate these threats and continually practice dealing with them. In support of this theory, Revonsuo shows that contemporary dreams comprise much more threatening events than people meet in daily non-dream life, and the dreamer usually engages appropriately with them.[73] It is suggested by this theory that dreams serve the purpose of allowing for the rehearsal of threatening scenarios in order to better prepare an individual for real-life threats.

According to Tsoukalas (2012) the biology of dreaming is related to the reactive patterns elicited by predatorial encounters (especially the tonic immobility reflex), a fact that lends support to evolutionary theories claiming that dreams specialize in threat avoidance and/or emotional processing.[51]

Psychosomatic theory of dreams

Y.D. Tsai developed in 1995 a 3-hypothesis theory[74] that is claimed to provide a mechanism for mind-body interaction and explain many dream-related phenomena, including hypnosis, meridians in Chinese medicine, the increase in heart rate and breathing rate during REM sleep, that babies have longer REM sleep, lucid dreams, etc.Dreams are a product of "dissociated imagination," which is dissociated from the conscious self and draws material from sensory memory for simulation, with feedback resulting in hallucination. By simulating the sensory signals to drive the autonomous nerves, dreams can affect mind-body interaction. In the brain and spine, the autonomous "repair nerves," which can expand the blood vessels, connect with compression and pain nerves. Repair nerves are grouped into many chains called meridians in Chinese medicine. When some repair nerves are prodded by compression or pain to send out their repair signals, a chain reaction spreads out to set other repair nerves in the same meridian into action. While dreaming, the body also employs the meridians to repair the body and help it grow and develop by simulating very intensive movement-compression signals to expand the blood vessels when the level of growth enzymes increase.

Other hypotheses on dreaming

There are many other hypotheses about the function of dreams, including:[75]- Dreams allow the repressed parts of the mind to be satisfied through fantasy while keeping the conscious mind from thoughts that would suddenly cause one to awaken from shock.[76]

- Ferenczi[77] proposed that the dream, when told, may communicate something that is not being said outright.

- Dreams regulate mood.[78]

- Hartmann[79] says dreams may function like psychotherapy, by "making connections in a safe place" and allowing the dreamer to integrate thoughts that may be dissociated during waking life.

- LaBerge and DeGracia[80] have suggested that dreams may function, in part, to recombine unconscious elements within consciousness on a temporary basis by a process they term "mental recombination", in analogy with genetic recombination of DNA. From a bio-computational viewpoint, mental recombination may contribute to maintaining an optimal information processing flexibility in brain information networks.

- Herodotus in his The Histories, writes "The visions that occur to us in dreams are, more often than not, the things we have been concerned about during the day."[81]

Dream content

From the 1940s to 1985, Calvin S. Hall collected more than 50,000 dream reports at Western Reserve University. In 1966 Hall and Van De Castle published The Content Analysis of Dreams, in which they outlined a coding system to study 1,000 dream reports from college students.[82] Results indicated that participants from varying parts of the world demonstrated similarity in their dream content.Hall's complete dream reports became publicly available in the mid-1990s by Hall's protégé William Domhoff, allowing further different analysis.

Visuals

The visual nature of dreams is generally highly phantasmagoric; that is, different locations and objects continuously blend into each other. The visuals (including locations, characters/people, objects/artifacts) are generally reflective of a person's memories and experiences, but banter can take on highly exaggerated and bizarre forms.People who are blind from birth do not have visual dreams. Their dream contents are related to other senses like auditory, touch, smell and taste, whichever are present since birth.[83]

Emotions

In the Hall study, the most common emotion experienced in dreams was anxiety. Other emotions included abandonment, anger, fear, joy, and happiness. Negative emotions were much more common than positive ones.[82]Sexual themes

The Hall data analysis shows that sexual dreams occur no more than 10% of the time and are more prevalent in young to mid-teens.[82] Another study showed that 8% of both men and women's dreams have sexual content.[84] In some cases, sexual dreams may result in orgasms or nocturnal emissions. These are colloquially known as wet dreams.[85]Color vs. black and white

A small minority of people say that they dream only in black and white.[86] A 2008 study by a researcher at the University of Dundee found that people who were only exposed to black and white television and film in childhood reported dreaming in black and white about 25% of the time.[87]Relationship with medical conditions

There is evidence that certain medical conditions (normally only neurological conditions) can impact dreams. For instance, some people with synesthesia have never reported entirely black-and-white dreaming, and often have a difficult time imagining the idea of dreaming in only black and white.[88]Dream interpretations

Dream interpretation can be a result of subjective ideas and experiences. A recent study conducted by the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology concluded that most people believe that "their dreams reveal meaningful hidden truths". The study was conducted in the United States, South Korea and India. 74% Indians, 65% South Koreans and 56% Americans believe this.[89]Therapy for recurring nightmares (often associated with posttraumatic stress disorder) can include imagining alternative scenarios that could begin at each step of the dream.[90]

Other associated phenomena

Incorporation of reality

During the night, many external stimuli may bombard the senses, but the brain often interprets the stimulus and makes it a part of a dream to ensure continued sleep.[91] Dream incorporation is a phenomenon whereby an actual sensation, such as environmental sounds, is incorporated into dreams, such as hearing a phone ringing in a dream while it is ringing in reality or dreaming of urination while wetting the bed. The mind can, however, awaken an individual if they are in danger or if trained to respond to certain sounds, such as a baby crying.The term "dream incorporation" is also used in research examining the degree to which preceding daytime events become elements of dreams. Recent studies suggest that events in the day immediately preceding, and those about a week before, have the most influence.[92]

Apparent precognition of real events

According to surveys, it is common for people to feel their dreams are predicting subsequent life events.[93] Psychologists have explained these experiences in terms of memory biases, namely a selective memory for accurate predictions and distorted memory so that dreams are retrospectively fitted onto life experiences.[93] The multi-faceted nature of dreams makes it easy to find connections between dream content and real events.[94]In one experiment, subjects were asked to write down their dreams in a diary. This prevented the selective memory effect, and the dreams no longer seemed accurate about the future.[95] Another experiment gave subjects a fake diary of a student with apparently precognitive dreams. This diary described events from the person's life, as well as some predictive dreams and some non-predictive dreams. When subjects were asked to recall the dreams they had read, they remembered more of the successful predictions than unsuccessful ones.[96]

Lucid dreaming

Lucid dreaming is the conscious perception of one's state while dreaming. In this state the dreamer may often (but not always) have some degree of control over their own actions within the dream or even the characters and the environment of the dream. Dream control has been reported to improve with practiced deliberate lucid dreaming, but the ability to control aspects of the dream is not necessary for a dream to qualify as "lucid" — a lucid dream is any dream during which the dreamer knows they are dreaming.[97] The occurrence of lucid dreaming has been scientifically verified.[98]Oneironaut is a term sometimes used for those who lucidly dream.

Communication through lucid dreaming

In 1975, parapsychologist Keith Hearne successfully communicated to a patient experiencing a lucid dream. On April 12, 1975, after being instructed to move the eyes left and right upon becoming lucid, the subject had a lucid dream and the first recorded signals from a lucid dream were recorded.[99]Years later, psychophysiologist Stephen LaBerge conducted similar work including:

- Using eye signals to map the subjective sense of time in dreams

- Comparing the electrical activity of the brain while singing awake and while dreaming.

- Studies comparing in-dream sex, arousal, and orgasm[100]

Dreams of absent-minded transgression

Dreams of absent-minded transgression (DAMT) are dreams wherein the dreamer absentmindedly performs an action that he or she has been trying to stop (one classic example is of a quitting smoker having dreams of lighting a cigarette). Subjects who have had DAMT have reported waking with intense feelings of guilt. One study found a positive association between having these dreams and successfully stopping the behavior.[101]Recalling dreams

The recall of dreams is extremely unreliable, though it is a skill that can be trained. Dreams can usually be recalled if a person is awakened while dreaming.[90] Women tend to have more frequent dream recall than men.[90] Dreams that are difficult to recall may be characterized by relatively little affect, and factors such as salience, arousal, and interference play a role in dream recall. Often, a dream may be recalled upon viewing or hearing a random trigger or stimulus. The salience hypothesis proposes that dream content that is salient, that is, novel, intense, or unusual, is more easily remembered. There is considerable evidence that vivid, intense, or unusual dream content is more frequently recalled.[102] A dream journal can be used to assist dream recall, for personal interest or psychotherapy purposes.For some people, sensations from the previous night's dreams are sometimes spontaneously experienced in falling asleep. However they are usually too slight and fleeting to allow dream recall. At least 95% of all dreams are not remembered. Certain brain chemicals necessary for converting short-term memories into long-term ones are suppressed during REM sleep. Unless a dream is particularly vivid and if one wakes during or immediately after it, the content of the dream is not remembered.[103]

Individual differences

In line with the salience hypothesis, there is considerable evidence that people who have more vivid, intense or unusual dreams show better recall. There is evidence that continuity of consciousness is related to recall. Specifically, people who have vivid and unusual experiences during the day tend to have more memorable dream content and hence better dream recall. People who score high on measures of personality traits associated with creativity, imagination, and fantasy, such as openness to experience, daydreaming, fantasy proneness, absorption, and hypnotic susceptibility, tend to show more frequent dream recall.[102] There is also evidence for continuity between the bizarre aspects of dreaming and waking experience. That is, people who report more bizarre experiences during the day, such as people high in schizotypy (psychosis proneness) have more frequent dream recall and also report more frequent nightmares.[102]Déjà vu

One theory of déjà vu attributes the feeling of having previously seen or experienced something to having dreamt about a similar situation or place, and forgetting about it until one seems to be mysteriously reminded of the situation or the place while awake.[104]Daydreaming

A daydream is a visionary fantasy, especially one of happy, pleasant thoughts, hopes or ambitions, imagined as coming to pass, and experienced while awake.[105] There are many different types of daydreams, and there is no consistent definition amongst psychologists.[105] The general public also uses the term for a broad variety of experiences. Research by Harvard psychologist Deirdre Barrett has found that people who experience vivid dream-like mental images reserve the word for these, whereas many other people refer to milder imagery, realistic future planning, review of past memories or just "spacing out"—i.e. one's mind going relatively blank—when they talk about "daydreaming."[106]While daydreaming has long been derided as a lazy, non-productive pastime, it is now commonly acknowledged that daydreaming can be constructive in some contexts.[107] There are numerous examples of people in creative or artistic careers, such as composers, novelists and filmmakers, developing new ideas through daydreaming. Similarly, research scientists, mathematicians and physicists have developed new ideas by daydreaming about their subject areas.