From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Human spaceflight (also referred to as manned spaceflight) is space travel with a crew aboard the spacecraft.

When a spacecraft is crewed, it can be operated directly, as opposed to being remotely operated or autonomous.

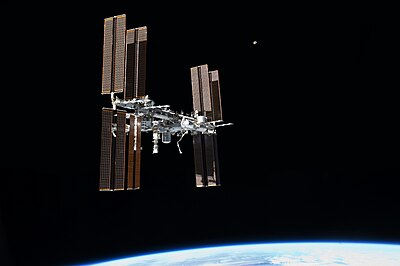

The first human spaceflight was launched by the Soviet Union on 12 April 1961 as a part of the Vostok program, with cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin aboard. Humans have been continually present in space for 14 years and 139 days on the International Space Station.

Since the retirement of the US Space Shuttle in 2011, only Russia and China have maintained domestic human spaceflight capability with the Soyuz program and Shenzhou program. Currently, all crewed flights to the International Space Station use Soyuz vehicles, which remain attached to the station to allow quick return if needed. The United States is developing commercial crew transportation to facilitate domestic access to ISS and low Earth orbit, as well as the Orion vehicle for beyond-low Earth orbit applications.

While spaceflight has typically been a government-directed activity, commercial spaceflight has gradually been taking on a greater role. The first private human spaceflight took place on 21 June 2004, when SpaceShipOne conducted a suborbital flight, and a number of non-governmental companies have been working to develop a space tourism industry. NASA has also played a role to stimulate private spaceflight through programs such as Commercial Orbital Transportation Services (COTS) and Commercial Crew Development (CCDev). With its 2011 budget proposals released in 2010,[1] the Obama administration moved towards a model where commercial companies would supply NASA with transportation services of both crew and cargo to low Earth orbit. The vehicles used for these services could then serve both NASA and potential commercial customers. Commercial resupply of ISS began two years after the retirement of the Shuttle, and commercial crew launches could begin by 2017.[2]

History

| Orbital human spaceflight | ||

| Name | Debut | Launches |

|---|---|---|

| Vostok | 1961 | 6 |

| Mercury | 1962 | 4 |

| Voskhod | 1964 | 2 |

| Gemini | 1965 | 10 |

| Soyuz | 1967 | 120 |

| Apollo/Skylab | 1968 | 15 |

| Shuttle | 1981 | 135 |

| Shenzhou | 2003 | 5 |

| Suborbital human spaceflight | ||

| Name | Debut | Flights |

| Mercury | 1961 | 2 |

| X-15 | 1963 | 2 |

| (Soyuz 18a, Soyuz T-10-1) | 1975, 1983 | 2 |

| SpaceShipOne | 2004 | 3 |

First human spaceflights

The first human spaceflight took place on 12 April 1961, when cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin made one orbit around the Earth aboard the Vostok 1 spacecraft, launched by the Soviet space program. Valentina Tereshkova became the first woman in space aboard Vostok 6 on 16 June 1963. Both spacecraft were launched by Vostok 3KA launch vehicles. Alexei Leonov made the first spacewalk when he left Voskhod 2 on 8 March 1965.Svetlana Savitskaya became the first woman to do so on 25 July 1984.

The United States became the second nation to put a human in space with the suborbital flight of astronaut Alan Shepard aboard Freedom 7 as part of Project Mercury. The spacecraft was launched on 5 May 1961 on a Redstone rocket. The first U.S. orbital flight was that of John Glenn aboard Friendship 7, launched 20 February 1962 on an Atlas rocket. From 1981 to 2011, the U.S. conducted all its human spaceflight missions with reusable space shuttles. Sally Ride became the first American woman in space in 1983. Eileen Collins was the first female shuttle pilot, and with shuttle mission STS-93 in 1999 she became the first woman to command a U.S. spacecraft.

China became the third nation to achieve independent human spaceflight capability when Yang Liwei launched into space on a Chinese-made vehicle, the Shenzhou 5, on 15 October 2003. The first Chinese woman, Liu Yang, was launched in June 2012 aboard Shenzhou 9. Previous European (Hermes) and Japanese (HOPE-X) domestic human spaceflight programs were abandoned after years of development, as was the first Chinese attempt, the Shuguang spacecraft.

The farthest destination for a human spaceflight mission has been the Moon. The only manned missions to the Moon have been those conducted by NASA as part of the Apollo program. The first such mission, Apollo 8, orbited the Moon but did not land. The first Moon landing mission was Apollo 11, during which—on 20 July 1969—Neil Armstrong and Buzz Aldrin became the first people to set foot on the Moon. Six missions landed in total, numbered Apollo 11–17, excluding Apollo 13. Altogether 12 men walked on the Moon, the only humans to have been on an extraterrestrial body. The Soviet Union discontinued its program for lunar orbiting and landing of human spaceflight missions in 1974 when Valentin Glushko became General Designer of NPO Energiya.[3]

The longest single human spaceflight is that of Valeriy Polyakov, who left Earth on 8 January 1994, and did not return until 22 March 1995 (a total of 437 days 17 hr. 58 min. 16 sec.). Sergei Krikalyov has spent the most time of anyone in space, 803 days, 9 hours, and 39 minutes altogether. The longest period of continuous human presence in space is 14 years and 139 days on the International Space Station, exceeding the previous record of almost 10 years (or 3,634 days) held by Mir, spanning the launch of Soyuz TM-8 on 5 September 1989 to the landing of Soyuz TM-29 on 28 August 1999.

For many years beginning in 1961, only two countries, the USSR (later Russia) and the United States, had their own astronauts. Citizens of other nations flew in space, beginning with the flight of Vladimir Remek, a Czech, on a Soviet spacecraft on 2 March 1978. As of 2010[update], citizens from 38 nations (including space tourists) have flown in space aboard Soviet, American, Russian, and Chinese spacecraft.

-

Freedom 7, the first U.S. sub-orbital human space mission

-

Valentina Tereshkova, the first woman cosmonaut, 1963

-

Post-shuttle gap in United States human spaceflight capability

Under the Bush administration, the Constellation Program included plans for retiring the Shuttle program and replacing it with the capability for spaceflight beyond low Earth orbit. In the 2011 United States federal budget, the Obama administration cancelled Constellation for being over budget and behind schedule while not innovating and investing in critical new technologies.[4] For beyond low earth orbit human spaceflight NASA is developing the Orion spacecraft to be launched by the Space Launch System. Under the Commercial Crew Development plan,NASA will rely on transportation services provided by the private sector to reach low earth orbit, such as Space X's Falcon 9/Dragon V2, Sierra Nevada Corporation's Dream Chaser, or Boeing's CST-100. The period between the retirement of the shuttle in 2011 and the initial operational capability of new systems in 2017, similar to the gap between the end of Apollo in 1975 and the first space shuttle flight in 1981, is referred to by a presidential Blue Ribbon Committee as the U.S. human spaceflight gap.[5] Commercial sub-orbital spacecraft aimed at the space tourism market such as Scaled Composites SpaceshipTwo to be operated by Virgin Galactic, and XCOR's Lynx spaceplane are under development and could reach space before 2017.[6]

Space programs

An Apollo spacecraft with docking equipment, as photographed by the Soyuz crew during the Apollo-Soyuz mission. Human spaceflight has been a forum for both competition and cooperation.

Human spaceflight programs have been conducted by the former Soviet Union/Russian Federation, the United States, the People's Republic of China and by private spaceflight company Scaled Composites.

The Indian Space Research Organization (ISRO) begun work on pre project activities of human space flight mission programme.[7] The objective of Human Spaceflight Programme is to undertake a human spaceflight mission to carry a crew of two to Low Earth Orbit (LEO) and return them safely to a predefined destination on earth. The programme is proposed to be implemented in defined phases. Currently, the pre project activities are progressing with a focus on the development of critical technologies for subsystems such as Crew Module (CM), Environmental control and Life Support System (ECLSS), Crew Escape System, etc. A study for undertaking human space flight to carry human beings to low earth orbit and ensure their safe return has been made by the department. The department has initiated pre-project activities to study technical and managerial issues related to undertaking manned mission with an aim to build and demonstrate the country’s capability. The programme envisages the development of a fully autonomous orbital vehicle carrying 2 or 3 crew members to about 300 km low earth orbit and their safe return.

Several other countries and space agencies have announced and begun human spaceflight programs by their own technology, Japan (JAXA), Iran (ISA) and Malaysia (MNSA).

Currently the following spacecraft and spaceports are used for launching human spaceflights:

- Soyuz with Soyuz rocket—Baikonur Cosmodrome

- International Space Station (ISS)—Assembled in orbit; crews transported by Soyuz spacecraft

- Shenzhou spacecraft with Long March rocket—Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center

- Tiangong-1—crews transported by Shenzhou spacecraft

- Vostok—Baikonur Cosmodrome

- Mercury—Cape Canaveral Air Force Station

- Voskhod—Baikonur Cosmodrome

- X-15—Edwards Air Force Base,[8] (two internationally recognized suborbital flights in program)

- Gemini—Cape Canaveral Air Force Station

- Apollo—Kennedy Space Center (Apollo 7 at Cape Canaveral Air Force Station)

- Salyut space station—Baikonur Cosmodrome

- Almaz space station—Baikonur Cosmodrome (Almaz was a series of military space stations under cover of the civilian name Salyut)

- Skylab space station—Kennedy Space Center

- Mir space station—Baikonur Cosmodrome

- SpaceShipOne with White Knight—Mojave Spaceport

- Space Shuttle—Kennedy Space Center

Numerous private companies attempted human spaceflight programs in an effort to win the $10 million Ansari X Prize. The first private human spaceflight took place on 21 June 2004, when SpaceShipOne conducted a suborbital flight. SpaceShipOne captured the prize on 4 October 2004, when it accomplished two consecutive flights within one week. SpaceShipTwo, launching from the carrier aircraft White Knight Two, is planned to conduct regular suborbital space tourism.

Most of the time, the only humans in space are those aboard the ISS, whose crew of six spends up to six months at a time in low Earth orbit.

NASA and ESA use the term "human spaceflight" to refer to their programs of launching people into space. These endeavors have also been referred to as "manned space missions."

National spacefaring attempts

- This section lists all nations which have explored human spaceflight programs. This should not to be confused with nations with citizens who have traveled into space including space tourists, flown or intended to fly by foreign country's or non-domestic private space systems – these are not counted as national spacefaring attempts in this list.

Safety concerns

Planners of human spaceflight missions face a number of safety concerns.Life support

The immediate needs for breathable air and drinkable water are addressed by the life support system of the spacecraft.Medical issues

Medical consequences such as possible blindness and bone loss have been associated with human space flight.[18][19]On 31 December 2012, a NASA-supported study reported that spaceflight may harm the brain of astronauts and accelerate the onset of Alzheimer's disease.[20][21][22]

Effects of microgravity

Medical data from astronauts in low earth orbits for long periods, dating back to the 1970s, show several adverse effects of a microgravity environment: loss of bone density, decreased muscle strength and endurance, postural instability, and reductions in aerobic capacity. Over time these deconditioning effects can impair astronauts’ performance or increase their risk of injury.[23]

In a weightless environment, astronauts put almost no weight on the back muscles or leg muscles used for standing up. Those muscles then start to weaken and eventually get smaller. If there is an emergency at landing, the loss of muscles, and consequently the loss of strength can be a serious problem. Sometimes, astronauts can lose up to 25% of their muscle mass on long term flights. When they get back to ground, they will be considerably weakened and will be out of action for a while.[citation needed]

Astronauts experiencing weightlessness will often lose their orientation, get motion sickness, and lose their sense of direction as their bodies try to get used to a weightless environment. When they get back to Earth, or any other mass with gravity, they have to readjust to the gravity and may have problems standing up, focusing their gaze, walking and turning. Importantly, those body motor disturbances after changing from different gravities only get worse the longer the exposure to little gravity.[citation needed] These changes will affect operational activities including approach and landing, docking, remote manipulation, and emergencies that may happen while landing. This can be a major roadblock to mission success.[citation needed]

In addition, after long space flight missions, male astronauts may experience severe eyesight problems.[24][25][26][27][28] Such eyesight problems may be a major concern for future deep space flight missions, including a manned mission to the planet Mars.[24][25][26][27][29]

Radiation

Without proper shielding, the crews of missions beyond low Earth orbit (LEO) might be at risk from high-energy protons emitted by solar flares. Lawrence Townsend of the University of Tennessee and others have studied the most powerful solar flare ever recorded. That flare was seen by the British astronomer Richard Carrington in September 1859. Radiation doses astronauts would receive from a Carrington-type flare could cause acute radiation sickness and possibly even death.[30]Another type of radiation, galactic cosmic rays, presents further challenges to human spaceflight beyond LEO.[31]

See also: Health threat from cosmic rays

Radiation damage to the immune system

There is also some scientific concern that extended spaceflight might slow down the body’s ability to protect itself against diseases.[32] Some of the problems are a weakened immune system and the activation of dormant viruses in the body. Radiation can cause both short and long term consequences to the bone marrow stem cells which create the blood and immune systems. Because the interior of a spacecraft is so small, a weakened immune system and more active viruses in the body can lead to a fast spread of infection.[citation needed]

Isolation

During long missions, astronauts are isolated and confined into small spaces. Depression, cabin fever and other psychological problems may impact the crew's safety and mission success.[citation needed]Astronauts may not be able to quickly return to Earth or receive medical supplies, equipment or personnel if a medical emergency occurs. The astronauts may have to rely for long periods on their limited existing resources and medical advice from the ground.

Launch safety

Reentry safety

Reliability

Fatality risk

As of 2010[update], 18 crew members have died during actual spaceflight missions (see table). Over 100 others have died in accidents during activity directly related to spaceflight missions or testing.| Year | #of

Deaths |

Mission | Known or likely cause | Accident description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1967 | 1 | Soyuz 1 | Trauma from crash landing | Spacecraft parachutes malfunctioned during descent, resulting in a crash landing. |

| 1971 | 3 | Soyuz 11 | Asphyxia | Valve opened upon Orbital Module separation before re-entry, causing descent module to depressurize. The crew are considered to be the only humans to have died in space - all other disasters on this list occurred during phases of the flight well below the Kármán line that marks the edge of space. |

| 1986 | 7 | Space Shuttle Challenger (Mission STS-51L) | Asphyxia from cabin breach or trauma from water impact[33] | An O-ring in the right Solid Rocket Booster failed, allowing hot gases to penetrate the casing of the booster. The escaping hot rocket exhaust led to failures of the External Tank and a strut connecting the booster to the tank. The result was a rapid burn of the fuel in the external tank which gave the appearance of an explosion. The orbiter itself did not explode, but rather broke up due to abnormal aerodynamic forces. |

| 2003 | 7 | Space Shuttle Columbia (Mission STS-107) | Asphyxia from cabin breach, trauma from dynamic load environment as orbiter broke up[34] | During launch, a piece of insulation foam broke off of the External Tank and struck the left wing, causing damage to a reinforced carbon-carbon panel on the wing's leading edge. Although the foam strike was detected after the launch, it was not seen as a concern, and the extent of the damage went undetected. When the shuttle re-entered the atmosphere, hot atmospheric gases penetrated through the hole in the left wing. Eventually, the shuttle lost control and subsequently disintegrated. |