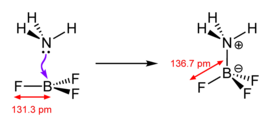

Diagram of some Lewis bases and acids

A Lewis acid is a chemical species that contains an empty orbital which is capable of accepting an electron pair from a Lewis base to form a Lewis adduct. A Lewis base, then, is any species that has a filled orbital containing an electron pair which is not involved in bonding but may form a dative bond with a Lewis acid to form a Lewis adduct. For example, NH3 is a Lewis base, because it can donate its lone pair of electrons. Trimethylborane (Me3B) is a Lewis acid as it is capable of accepting a lone pair. In a Lewis adduct, the Lewis acid and base share an electron pair furnished by the Lewis base, forming a dative bond.[1] In the context of a specific chemical reaction between NH3 and Me3B, the lone pair from NH3 will form a dative bond with the empty orbital of Me3B to form an adduct NH3•BMe3. The terminology refers to the contributions of Gilbert N. Lewis.[2]

Depicting adducts

In many cases, the interaction between the Lewis base and Lewis acid in a complex is indicated by an arrow indicating the Lewis base donating electrons toward the Lewis acid using the notation of a dative bond—for example, Me3B←NH3. Some sources indicate the Lewis base with a pair of dots (the explicit electrons being donated), which allows consistent representation of the transition from the base itself to the complex with the acid:- Me3B + :NH3 → Me3B:NH3

Examples

Major structural changes accompany binding of the Lewis base to the coordinatively unsaturated, planar Lewis acid BF3.

Classically, the term "Lewis acid" is restricted to trigonal planar species with an empty p orbital, such as BR3 where R can be an organic substituent or a halide.[citation needed] For the purposes of discussion, even complex compounds such as Et3Al2Cl3 and AlCl3 are treated as trigonal planar Lewis acids. Metal ions such as Na+, Mg2+, and Ce3+, which are invariably complexed with additional ligands, are often sources of coordinatively unsaturated derivatives that form Lewis adducts upon reaction with a Lewis base. Other reactions might simply be referred to as "acid-catalyzed" reactions. Some compounds, such as H2O, are both Lewis acids and Lewis bases, because they can either accept a pair of electrons or donate a pair of electrons, depending upon the reaction.

Lewis acids are diverse. Simplest are those that react directly with the Lewis base. But more common are those that undergo a reaction prior to forming the adduct.

- Examples of Lewis acids based on the general definition of electron pair acceptor include:

- the proton (H+) and acidic compounds onium ions, such as NH4+ and H3O+

- high oxidation state transition metal cations, e.g., Fe3+;

- other metal cations, such as Li+ and Mg2+, often as their aquo or ether complexes,

- trigonal planar species, such as BF3 and carbocations H3C+

- pentahalides of phosphorus, arsenic, and antimony

- electron poor π-systems, such as enones and tetracyanoethylenes.

Simple Lewis acids

Some of the most studied examples of such Lewis acids are the boron trihalides and organoboranes, but other compounds exhibit this behavior:- BF3 + F− → BF4−

- BF3 + OMe2 → BF3OMe2

In many cases, the adducts violate the octet rule, such as the triiodide anion:

- I2 + I− → I3−

In some cases, the Lewis acids are capable of binding two Lewis bases, a famous example being the formation of hexafluorosilicate:

- SiF4 + 2 F− → SiF62−

Complex Lewis acids

Most compounds considered to be Lewis acids require an activation step prior to formation of the adduct with the Lewis base. Well known cases are the aluminium trihalides, which are widely viewed as Lewis acids. Aluminium trihalides, unlike the boron trihalides, do not exist in the form AlX3, but as aggregates and polymers that must be degraded by the Lewis base.[4] A simpler case is the formation of adducts of borane. Monomeric BH3 does not exist appreciably, so the adducts of borane are generated by degradation of diborane:- B2H6 + 2 H− → 2 BH4−

Many metal complexes serve as Lewis acids, but usually only after dissociating a more weakly bound Lewis base, often water.

- [Mg(H2O)6]2+ + 6 NH3 → [Mg(NH3)6]2+ + 6 H2O

H+ as Lewis acid

The proton (H+) [5] is one of the strongest but is also one of the most complicated Lewis acids. It is convention to ignore the fact that a proton is heavily solvated (bound to solvent). With this simplification in mind, acid-base reactions can be viewed as the formation of adducts:- H+ + NH3 → NH4+

- H+ + OH− → H2O

Applications of Lewis acids

A typical example of a Lewis acid in action is in the Friedel–Crafts alkylation reaction.[3] The key step is the acceptance by AlCl3 of a chloride ion lone-pair, forming AlCl4− and creating the strongly acidic, that is, electrophilic, carbonium ion.- RCl +AlCl3 → R+ + AlCl4−

Lewis bases

A Lewis base is an atomic or molecular species where the highest occupied molecular orbital (HOMO) is highly localized. Typical Lewis bases are conventional amines such as ammonia and alkyl amines. Other common Lewis bases include pyridine and its derivatives. Some of the main classes of Lewis bases are- amines of the formula NH3−xRx where R = alkyl or aryl. Related to these are pyridine and its derivatives.

- phosphines of the formula PR3−xAx, where R = alkyl, A = aryl.

- compounds of O, S, Se and Te in oxidation state 2, including water, ethers, ketones

- Examples of Lewis bases based on the general definition of electron pair donor include:

Heats of binding of various bases to BF3

| Lewis base | Donor atom | Enthalpy of complexation (kJ/mol) |

|---|---|---|

| Et3N | N | 135 |

| quinuclidine | N | 150 |

| pyridine | N | 128 |

| Acetonitrile | N | 60 |

| Et2O | O | 78.8 |

| THF | O | 90.4 |

| acetone | O | 76.0 |

| EtOAc | O | 75.5 |

| DMA | O | 112 |

| DMSO | O | 105 |

| Tetrahydrothiophene | S | 51.6 |

| Trimethylphosphine | P | 97.3 |

Applications of Lewis bases

Nearly all electron pair donors that form compounds by binding transition elements can be viewed as a collections of the Lewis bases – or ligands. Thus a large application of Lewis bases is to modify the activity and selectivity of metal catalysts. Chiral Lewis bases thus confer chirality on a catalyst, enabling asymmetric catalysis, which is useful for the production of pharmaceuticals.Many Lewis bases are "multidentate," that is they can form several bonds to the Lewis acid. These multidentate Lewis bases are called chelating agents.

Hard and soft classification

Lewis acids and bases are commonly classified according to their hardness or softness. In this context hard implies small and nonpolarizable and soft indicates larger atoms that are more polarizable.- typical hard acids: H+, alkali/alkaline earth metal cations, boranes, Zn2+

- typical soft acids: Ag+, Mo(0), Ni(0), Pt2+

- typical hard bases: ammonia and amines, water, carboxylates, fluoride and chloride

- typical soft bases: organophosphines, thioethers, carbon monoxide, iodide

ECW model

The ECW model is quantitative model that describes and predicts the strength of Lewis acid base interactions, −ΔH . The model assigned E and C parameters to many Lewis acids and bases. Each acid is characterized by an EA and a CA. Each base is likewise characterized by its own EB and CB. The E and C parameters refer, respectively, to the electrostatic and covalent contributions to the strength of the bonds that the acid and base will form. The equation is- −ΔH = EAEB + CACB + W

There is no single order of Lewis base strengths

Cramer–Bopp plots show graphically using the E and C parameters of the ECW model that there is no one single order of Lewis base strengths (or acid strengths).[8] Single property or variable scales are limited to a small range of acids or bases.History

MO diagram depicting the formation of a dative covalent bond between two atoms.

The concept originated with Gilbert N. Lewis who studied chemical bonding. In 1923, Lewis wrote An acid substance is one which can employ an electron lone pair from another molecule in completing the stable group of one of its own atoms.[9][10] The Brønsted–Lowry acid–base theory was published in the same year. The two theories are distinct but complementary. A Lewis base is also a Brønsted–Lowry base, but a Lewis acid doesn't need to be a Brønsted–Lowry acid. The classification into hard and soft acids and bases (HSAB theory) followed in 1963. The strength of Lewis acid-base interactions, as measured by the standard enthalpy of formation of an adduct can be predicted by the Drago–Wayland two-parameter equation.

Reformulation of Lewis theory

Lewis had suggested in 1916 that two atoms are held together in a chemical bond by sharing a pair of electrons. When each atom contributed one electron to the bond it was called a covalent bond. When both electrons come from one of the atoms it was called a dative covalent bond or coordinate bond. The distinction is not very clear-cut. For example, in the formation of an ammonium ion from ammonia and hydrogen the ammonia molecule donates a pair of electrons to the proton;[5] the identity of the electrons is lost in the ammonium ion that is formed. Nevertheless, Lewis suggested that an electron-pair donor be classified as a base and an electron-pair acceptor be classified as acid.A more modern definition of a Lewis acid is an atomic or molecular species with a localized empty atomic or molecular orbital of low energy. This lowest energy molecular orbital (LUMO) can accommodate a pair of electrons.

Comparison with Brønsted–Lowry theory

A Lewis base is often a Brønsted–Lowry base as it can donate a pair of electrons to H+;[5] the proton is a Lewis acid as it can accept a pair of electrons. The conjugate base of a Brønsted–Lowry acid is also a Lewis base as loss of H+ from the acid leaves those electrons which were used for the A—H bond as a lone pair on the conjugate base. However, a Lewis base can be very difficult to protonate, yet still react with a Lewis acid. For example, carbon monoxide is a very weak Brønsted–Lowry base but it forms a strong adduct with BF3.In another comparison of Lewis and Brønsted–Lowry acidity by Brown and Kanner,[11] 2,6-di-t-butylpyridine reacts to form the hydrochloride salt with HCl but does not react with BF3. This example demonstrates that steric factors, in addition to electron configuration factors, play a role in determining the strength of the interaction between the bulky di-t-butylpyridine and tiny proton.

A Brønsted–Lowry acid is a proton donor, not an electron-pair acceptor.

![{\displaystyle {\ce {{NO2}->[h \nu] {NO}+ {O}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/34fed23155c119954fa08461965c09c3d04f2921)

![{\displaystyle {\ce {{NO2}+ {O2}->[h \nu] {NO}+ {O3}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1e1d3ed7bb48f69dfa453b9727ecbe7863804988)

![{\displaystyle {\ce {{CFCS}->[h \nu] {Cl.}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/088ca5853b063101511fb5a21520e648c6d87466)

![{\displaystyle {\ce {{O3}->[h \nu] {O}+ {O2}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f2db8df4adfc00e58fc18167823562cdbaa169d8)

![{\displaystyle {\ce {{2O3}->[h \nu] 3O2}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/29b154561607496cd0feb37e02045d192ecbb4e8)