From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The

interdisciplinary field of

materials science, also commonly termed

materials science and engineering is the design and discovery of new materials, particularly

solids. The intellectual origins of materials science stem from the

Enlightenment, when researchers began to use analytical thinking from

chemistry,

physics, and

engineering to understand ancient,

phenomenological observations in

metallurgy and

mineralogy.

Materials science still incorporates elements of physics, chemistry,

and engineering. As such, the field was long considered by academic

institutions as a sub-field of these related fields. Beginning in the

1940s, materials science began to be more widely recognized as a

specific and distinct field of science and engineering, and major

technical universities around the world created dedicated schools of the

study, within either the Science or Engineering schools, hence the

naming.

- Materials science is a syncretic discipline hybridizing

metallurgy, ceramics, solid-state physics, and chemistry. It is the

first example of a new academic discipline emerging by fusion rather

than fission.[3]

Many of the most pressing scientific problems humans currently face

are due to the limits of the materials that are available and how they

are used. Thus, breakthroughs in materials science are likely to affect

the future of technology significantly.

[4][5]

Materials scientists emphasize understanding how the history of a material (its

processing)

influences its structure, and thus the material's properties and

performance. The understanding of processing-structure-properties

relationships is called the

§ materials paradigm. This paradigm is used to advance understanding in a variety of research areas, including

nanotechnology,

biomaterials, and metallurgy. Materials science is also an important part of

forensic engineering and

failure analysis

- investigating materials, products, structures or components which

fail or do not function as intended, causing personal injury or damage

to property. Such investigations are key to understanding, for example,

the causes of various

aviation accidents and incidents.

History

The material of choice of a given era is often a defining point. Phrases such as

Stone Age,

Bronze Age,

Iron Age, and

Steel Age are historic, if arbitrary examples. Originally deriving from the manufacture of

ceramics

and its putative derivative metallurgy, materials science is one of the

oldest forms of engineering and applied science. Modern materials

science evolved directly from

metallurgy,

which itself evolved from mining and (likely) ceramics and earlier from

the use of fire. A major breakthrough in the understanding of materials

occurred in the late 19th century, when the American scientist

Josiah Willard Gibbs demonstrated that the

thermodynamic properties related to

atomic structure in various

phases are related to the physical properties of a material. Important elements of modern materials science are a product of the

space race: the understanding and

engineering of the metallic

alloys, and

silica and

carbon

materials, used in building space vehicles enabling the exploration of

space. Materials science has driven, and been driven by, the development

of revolutionary technologies such as

rubbers,

plastics,

semiconductors, and

biomaterials.

Before the 1960s (and in some cases decades after), many

materials science departments were named

metallurgy

departments, reflecting the 19th and early 20th century emphasis on

metals. The growth of materials science in the United States was

catalyzed in part by the

Advanced Research Projects Agency,

which funded a series of university-hosted laboratories in the early

1960s "to expand the national program of basic research and training in

the materials sciences."

[6] The field has since broadened to include every class of materials, including

ceramics,

polymers,

semiconductors,

magnetic materials,

medical implant

materials, biological materials, and nanomaterials, with modern

materials classed within 3 distinct groups: Ceramic, Metal or Polymer.

The prominent change in materials science during the last two decades is

active usage of computer simulation methods to find new compounds,

predict various properties, and as a result design new materials at a

much greater rate than previous years.

Fundamentals

The materials paradigm represented in the form of a tetrahedron.

A material is defined as a substance (most often a solid, but other

condensed phases can be included) that is intended to be used for

certain applications.

[7]

There are a myriad of materials around us—they can be found in anything

from buildings to spacecraft. Materials can generally be further

divided into two classes:

crystalline and

non-crystalline. The traditional examples of materials are

metals,

semiconductors,

ceramics and

polymers.

[8] New and advanced materials that are being developed include

nanomaterials,

biomaterials,

[9] and

energy materials to name a few.

The basis of materials science involves studying the structure of materials, and relating them to their

properties.

Once a materials scientist knows about this structure-property

correlation, they can then go on to study the relative performance of a

material in a given application. The major determinants of the structure

of a material and thus of its properties are its constituent chemical

elements and the way in which it has been processed into its final form.

These characteristics, taken together and related through the laws of

thermodynamics and

kinetics, govern a material's

microstructure, and thus its properties.

Structure

As

mentioned above, structure is one of the most important components of

the field of materials science. Materials science examines the structure

of materials from the atomic scale, all the way up to the macro scale.

Characterization is the way materials scientists examine the structure of a material. This involves methods such as diffraction with

X-rays,

electrons, or

neutrons, and various forms of

spectroscopy and

chemical analysis such as

Raman spectroscopy,

energy-dispersive spectroscopy (EDS),

chromatography,

thermal analysis,

electron microscope analysis, etc. Structure is studied at various levels, as detailed below.

Atomic structure

This

deals with the atoms of the materials, and how they are arranged to

give molecules, crystals, etc. Much of the electrical, magnetic and

chemical properties of materials arise from this level of structure. The

length scales involved are in angstroms.

The way in which the atoms and molecules are bonded and arranged is

fundamental to studying the properties and behavior of any material.

Nanostructure

Nanostructure deals with objects and structures that are in the 1—100 nm range.

[10]

In many materials, atoms or molecules agglomerate together to form

objects at the nanoscale. This causes many interesting electrical,

magnetic, optical, and mechanical properties.

In describing nanostructures it is necessary to differentiate between the number of dimensions on the

nanoscale.

Nanotextured surfaces have

one dimension on the nanoscale, i.e., only the thickness of the surface of an object is between 0.1 and 100 nm. Nanotubes have

two dimensions

on the nanoscale, i.e., the diameter of the tube is between 0.1 and

100 nm; its length could be much greater. Finally, spherical

nanoparticles have

three dimensions on the nanoscale, i.e., the particle is between 0.1 and 100 nm in each spatial dimension. The terms nanoparticles and

ultrafine particles

(UFP) often are used synonymously although UFP can reach into the

micrometre range. The term 'nanostructure' is often used when referring

to magnetic technology. Nanoscale structure in biology is often called

ultrastructure.

Materials which atoms and molecules form constituents in the

nanoscale (i.e., they form nanostructure) are called nanomaterials.

Nanomaterials are subject of intense research in the materials science

community due to the unique properties that they exhibit.

Microstructure

Microstructure of pearlite.

Microstructure is defined as the structure of a prepared surface or

thin foil of material as revealed by a microscope above 25×

magnification. It deals with objects from 100 nm to a few cm. The

microstructure of a material (which can be broadly classified into

metallic, polymeric, ceramic and composite) can strongly influence

physical properties such as strength, toughness, ductility, hardness,

corrosion resistance, high/low temperature behavior, wear resistance,

and so on. Most of the traditional materials (such as metals and

ceramics) are microstructured.

The manufacture of a perfect

crystal of a material is physically impossible. For example, any crystalline material will contain

defects such as

precipitates, grain boundaries (

Hall–Petch relationship),

vacancies, interstitial atoms or substitutional atoms. The

microstructure of materials reveals these larger defects, so that they

can be studied, with significant advances in simulation resulting in

exponentially increasing understanding of how defects can be used to

enhance material properties.

Macro structure

Macro

structure is the appearance of a material in the scale millimeters to

meters—it is the structure of the material as seen with the naked eye.

Crystallography

Crystal structure of a perovskite with a chemical formula ABX

3.

[11]

Crystallography is the science that examines the arrangement of atoms

in crystalline solids. Crystallography is a useful tool for materials

scientists. In single crystals, the effects of the crystalline

arrangement of atoms is often easy to see macroscopically, because the

natural shapes of crystals reflect the atomic structure. Further,

physical properties are often controlled by crystalline defects. The

understanding of crystal structures is an important prerequisite for

understanding crystallographic defects. Mostly, materials do not occur

as a single crystal, but in polycrystalline form, i.e., as an aggregate

of small crystals with different orientations. Because of this, the

powder diffraction method, which uses diffraction patterns of

polycrystalline samples with a large number of crystals, plays an

important role in structural determination.

Most materials have a crystalline structure, but some important

materials do not exhibit regular crystal structure.

Polymers display varying degrees of crystallinity, and many are completely noncrystalline.

Glass, some ceramics, and many natural materials are

amorphous,

not possessing any long-range order in their atomic arrangements. The

study of polymers combines elements of chemical and statistical

thermodynamics to give thermodynamic and mechanical, descriptions of

physical properties.

Bonding

To obtain a full understanding of the material structure and how it

relates to its properties, the materials scientist must study how the

different atoms, ions and molecules are arranged and bonded to each

other. This involves the study and use of

quantum chemistry or

quantum physics.

Solid-state physics,

solid-state chemistry and

physical chemistry are also involved in the study of bonding and structure.

Synthesis and processing

Synthesis

and processing involves the creation of a material with the desired

micro-nanostructure. From an engineering standpoint, a material cannot

be used in industry if no economical production method for it has been

developed. Thus, the processing of materials is vital to the field of

materials science.

Different materials require different processing or synthesis

methods. For example, the processing of metals has historically been

very important and is studied under the branch of materials science

named

physical metallurgy. Also, chemical and physical methods are also used to synthesize other materials such as

polymers,

ceramics,

thin films, etc. As of the early 21st century, new methods are being developed to synthesize nanomaterials such as

graphene.

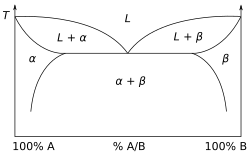

Thermodynamics

A phase diagram for a binary system displaying a eutectic point.

Thermodynamics is concerned with

heat and

temperature and their relation to

energy and

work. It defines

macroscopic variables, such as

internal energy,

entropy, and

pressure,

that partly describe a body of matter or radiation. It states that the

behavior of those variables is subject to general constraints, that are

common to all materials, not the peculiar properties of particular

materials. These general constraints are expressed in the four laws of

thermodynamics. Thermodynamics describes the bulk behavior of the body,

not the microscopic behaviors of the very large numbers of its

microscopic constituents, such as molecules. The behavior of these

microscopic particles is described by, and the laws of thermodynamics

are derived from,

statistical mechanics.

The study of thermodynamics is fundamental to materials science.

It forms the foundation to treat general phenomena in materials science

and engineering, including chemical reactions, magnetism,

polarizability, and elasticity. It also helps in the understanding of

phase diagrams and phase equilibrium.

Kinetics

Chemical kinetics

is the study of the rates at which systems that are out of equilibrium

change under the influence of various forces. When applied to materials

science, it deals with how a material changes with time (moves from

non-equilibrium to equilibrium state) due to application of a certain

field. It details the rate of various processes evolving in materials

including shape, size, composition and structure.

Diffusion is important in the study of kinetics as this is the most common mechanism by which materials undergo change.

Kinetics is essential in processing of materials because, among

other things, it details how the microstructure changes with application

of heat.

In research

Materials science has received much attention from researchers. In most universities, many departments ranging from

physics to

chemistry to

chemical engineering,

along with materials science departments, are involved in materials

research. Research in materials science is vibrant and consists of many

avenues. The following list is in no way exhaustive. It serves only to

highlight certain important research areas.

Nanomaterials

Nanomaterials describe, in principle, materials of which a single

unit is sized (in at least one dimension) between 1 and 1000 nanometers

(10

−9 meter) but is usually 1—100 nm.

Nanomaterials research takes a materials science-based approach to

nanotechnology, leveraging advances in materials

metrology and synthesis which have been developed in support of

microfabrication research. Materials with structure at the nanoscale often have unique optical, electronic, or mechanical properties.

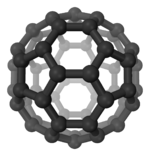

The field of nanomaterials is loosely organized, like the

traditional field of chemistry, into organic (carbon-based)

nanomaterials such as fullerenes, and inorganic nanomaterials based on

other elements, such as silicon. Examples of nanomaterials include

fullerenes,

carbon nanotubes,

nanocrystals, etc.

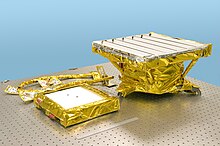

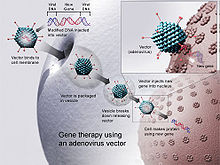

Biomaterials

A biomaterial is any matter, surface, or construct that interacts with biological systems. The study of biomaterials is called

bio materials science.

It has experienced steady and strong growth over its history, with many

companies investing large amounts of money into developing new

products. Biomaterials science encompasses elements of

medicine,

biology,

chemistry,

tissue engineering, and materials science.

Biomaterials can be derived either from nature or synthesized in a

laboratory using a variety of chemical approaches using metallic

components,

polymers,

bioceramics, or

composite materials.

They are often used and/or adapted for a medical application, and thus

comprises whole or part of a living structure or biomedical device which

performs, augments, or replaces a natural function. Such functions may

be benign, like being used for a

heart valve, or may be

bioactive with a more interactive functionality such as

hydroxylapatite coated

hip implants.

Biomaterials are also used every day in dental applications, surgery,

and drug delivery. For example, a construct with impregnated

pharmaceutical products can be placed into the body, which permits the

prolonged release of a drug over an extended period of time. A

biomaterial may also be an

autograft,

allograft or

xenograft used as an

organ transplant material.

Electronic, optical, and magnetic

Semiconductors, metals, and ceramics are used today to form highly

complex systems, such as integrated electronic circuits, optoelectronic

devices, and magnetic and optical mass storage media. These materials

form the basis of our modern computing world, and hence research into

these materials is of vital importance.

Semiconductors are a traditional example of these types of materials. They are materials that have properties that are intermediate between

conductors and

insulators. Their electrical conductivities are very sensitive to impurity concentrations, and this allows for the use of

doping to achieve desirable electronic properties. Hence, semiconductors form the basis of the traditional computer.

This field also includes new areas of research such as

superconducting materials,

spintronics,

metamaterials, etc. The study of these materials involves knowledge of materials science and

solid-state physics or

condensed matter physics.

Computational science and theory

With

the increase in computing power, simulating the behavior of materials

has become possible. This enables materials scientists to discover

properties of materials formerly unknown, as well as to design new

materials. Up until now, new materials were found by time-consuming

trial and error processes. But, now it is hoped that computational

methods could drastically reduce that time, and allow tailoring

materials properties. This involves simulating materials at all length

scales, using methods such as

density functional theory,

molecular dynamics, etc.

In industry

Radical

materials advances

can drive the creation of new products or even new industries, but

stable industries also employ materials scientists to make incremental

improvements and troubleshoot issues with currently used materials.

Industrial applications of materials science include materials design,

cost-benefit tradeoffs in industrial production of materials, processing

methods (

casting,

rolling,

welding,

ion implantation,

crystal growth,

thin-film deposition,

sintering,

glassblowing, etc.), and analytic methods (characterization methods such as

electron microscopy,

X-ray diffraction,

calorimetry,

nuclear microscopy (HEFIB),

Rutherford backscattering,

neutron diffraction, small-angle X-ray scattering (SAXS), etc.).

Besides material characterization, the material scientist or

engineer also deals with extracting materials and converting them into

useful forms. Thus ingot casting, foundry methods, blast furnace

extraction, and electrolytic extraction are all part of the required

knowledge of a materials engineer. Often the presence, absence, or

variation of minute quantities of secondary elements and compounds in a

bulk material will greatly affect the final properties of the materials

produced. For example, steels are classified based on 1/10 and 1/100

weight percentages of the carbon and other alloying elements they

contain. Thus, the extracting and purifying methods used to extract iron

in a blast furnace can affect the quality of steel that is produced.

Ceramics and glasses

Si3N4 ceramic bearing parts

Another application of material science is the structures of

ceramics and

glass

typically associated with the most brittle materials. Bonding in

ceramics and glasses uses covalent and ionic-covalent types with SiO

2

(silica or sand) as a fundamental building block. Ceramics are as soft

as clay or as hard as stone and concrete. Usually, they are crystalline

in form. Most glasses contain a metal oxide fused with silica. At high

temperatures used to prepare glass, the material is a viscous liquid.

The structure of glass forms into an amorphous state upon cooling.

Windowpanes and eyeglasses are important examples. Fibers of glass are

also available. Scratch resistant Corning

Gorilla Glass

is a well-known example of the application of materials science to

drastically improve the properties of common components. Diamond and

carbon in its graphite form are considered to be ceramics.

Engineering ceramics are known for their stiffness and stability

under high temperatures, compression and electrical stress. Alumina,

silicon carbide, and

tungsten carbide

are made from a fine powder of their constituents in a process of

sintering with a binder. Hot pressing provides higher density material.

Chemical vapor deposition can place a film of a ceramic on another

material. Cermets are ceramic particles containing some metals. The wear

resistance of tools is derived from cemented carbides with the metal

phase of cobalt and nickel typically added to modify properties.

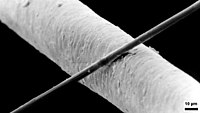

Composites

A 6 μm diameter carbon filament (running from bottom left to top right) siting atop the much larger human hair.

Filaments are commonly used for reinforcement in

composite materials.

Another application of materials science in industry is making

composite materials.

These are structured materials composed of two or more macroscopic

phases. Applications range from structural elements such as

steel-reinforced concrete, to the thermal insulating tiles which play a

key and integral role in NASA's

Space Shuttle thermal protection system which is used to protect the surface of the shuttle from the heat of re-entry into the Earth's atmosphere. One example is

reinforced Carbon-Carbon

(RCC), the light gray material which withstands re-entry temperatures

up to 1,510 °C (2,750 °F) and protects the Space Shuttle's wing leading

edges and nose cap. RCC is a laminated composite material made from

graphite rayon cloth and impregnated with a

phenolic resin.

After curing at high temperature in an autoclave, the laminate is

pyrolized to convert the resin to carbon, impregnated with furfural

alcohol in a vacuum chamber, and cured-pyrolized to convert the

furfural alcohol to carbon. To provide oxidation resistance for reuse ability, the outer layers of the RCC are converted to

silicon carbide.

Other examples can be seen in the "plastic" casings of television

sets, cell-phones and so on. These plastic casings are usually a

composite material made up of a thermoplastic matrix such as

acrylonitrile butadiene styrene (ABS) in which

calcium carbonate chalk,

talc,

glass fibers or

carbon fibers

have been added for added strength, bulk, or electrostatic dispersion.

These additions may be termed reinforcing fibers, or dispersants,

depending on their purpose.

Polymers

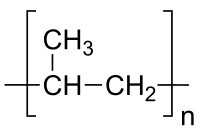

The repeating unit of the polymer polypropylene

Expanded polystyrene polymer packaging.

Polymers

are chemical compounds made up of a large number of identical

components linked together like chains. They are an important part of

materials science. Polymers are the raw materials (the resins) used to

make what are commonly called plastics and rubber. Plastics and rubber

are really the final product, created after one or more polymers or

additives have been added to a resin during processing, which is then

shaped into a final form. Plastics which have been around, and which are

in current widespread use, include

polyethylene,

polypropylene,

polyvinyl chloride (PVC),

polystyrene,

nylons,

polyesters,

acrylics,

polyurethanes, and

polycarbonates and also rubbers which have been around are natural rubber,

styrene-butadiene rubber,

chloroprene, and

butadiene rubber. Plastics are generally classified as

commodity,

specialty and

engineering plastics.

Polyvinyl chloride (PVC) is widely used, inexpensive, and annual

production quantities are large. It lends itself to a vast array of

applications, from

artificial leather to

electrical insulation and cabling,

packaging, and

containers. Its fabrication and processing are simple and well-established. The versatility of PVC is due to the wide range of

plasticisers

and other additives that it accepts. The term "additives" in polymer

science refers to the chemicals and compounds added to the polymer base

to modify its material properties.

Polycarbonate

would be normally considered an engineering plastic (other examples

include PEEK, ABS). Such plastics are valued for their superior

strengths and other special material properties. They are usually not

used for disposable applications, unlike commodity plastics.

Specialty plastics are materials with unique characteristics,

such as ultra-high strength, electrical conductivity,

electro-fluorescence, high thermal stability, etc.

The dividing lines between the various types of plastics is not

based on material but rather on their properties and applications. For

example,

polyethylene

(PE) is a cheap, low friction polymer commonly used to make disposable

bags for shopping and trash, and is considered a commodity plastic,

whereas

medium-density polyethylene (MDPE) is used for underground gas and water pipes, and another variety called

ultra-high-molecular-weight polyethylene

(UHMWPE) is an engineering plastic which is used extensively as the

glide rails for industrial equipment and the low-friction socket in

implanted

hip joints.

Metal alloys

Wire rope made from

steel alloy.

The study of metal alloys is a significant part of materials science.

Of all the metallic alloys in use today, the alloys of iron (

steel,

stainless steel,

cast iron,

tool steel,

alloy steels)

make up the largest proportion both by quantity and commercial value.

Iron alloyed with various proportions of carbon gives low, mid and

high carbon steels. An iron-carbon alloy is only considered steel if the carbon level is between 0.01% and 2.00%. For the steels, the

hardness

and tensile strength of the steel is related to the amount of carbon

present, with increasing carbon levels also leading to lower ductility

and toughness. Heat treatment processes such as quenching and tempering

can significantly change these properties, however. Cast Iron is defined

as an iron–carbon alloy with more than 2.00% but less than 6.67%

carbon. Stainless steel is defined as a regular steel alloy with greater

than 10% by weight alloying content of Chromium. Nickel and Molybdenum

are typically also found in stainless steels.

Other significant metallic alloys are those of

aluminium,

titanium,

copper and

magnesium.

Copper alloys have been known for a long time (since the

Bronze Age),

while the alloys of the other three metals have been relatively

recently developed. Due to the chemical reactivity of these metals, the

electrolytic extraction processes required were only developed

relatively recently. The alloys of aluminium, titanium and magnesium are

also known and valued for their high strength-to-weight ratios and, in

the case of magnesium, their ability to provide electromagnetic

shielding. These materials are ideal for situations where high

strength-to-weight ratios are more important than bulk cost, such as in

the aerospace industry and certain automotive engineering applications.

Semiconductors

The study of semiconductors is a significant part of materials science. A

semiconductor

is a material that has a resistivity between a metal and insulator. Its

electronic properties can be greatly altered through intentionally

introducing impurities or doping. From these semiconductor materials,

things such as

diodes,

transistors,

light-emitting diodes (LEDs), and analog and digital

electric circuits

can be built, making them materials of interest in industry.

Semiconductor devices have replaced thermionic devices (vacuum tubes) in

most applications. Semiconductor devices are manufactured both as

single discrete devices and as

integrated circuits

(ICs), which consist of a number—from a few to millions—of devices

manufactured and interconnected on a single semiconductor substrate.

[14]

Of all the semiconductors in use today,

silicon

makes up the largest portion both by quantity and commercial value.

Monocrystalline silicon is used to produce wafers used in the

semiconductor and electronics industry. Second to silicon,

gallium arsenide

(GaAs) is the second most popular semiconductor used. Due to its higher

electron mobility and saturation velocity compared to silicon, it is a

material of choice for high-speed electronics applications. These

superior properties are compelling reasons to use GaAs circuitry in

mobile phones, satellite communications, microwave point-to-point links

and higher frequency radar systems. Other semiconductor materials

include

germanium,

silicon carbide, and

gallium nitride and have various applications.

Relation to other fields

Materials

science evolved—starting from the 1960s—because it was recognized that

to create, discover and design new materials, one had to approach it in a

unified manner. Thus, materials science and engineering emerged at the

intersection of various fields such as

metallurgy,

solid state physics,

chemistry,

chemical engineering,

mechanical engineering and

electrical engineering.

The field is inherently

interdisciplinary,

and the materials scientists/engineers must be aware and make use of

the methods of the physicist, chemist and engineer. The field thus

maintains close relationships with these fields. Also, many physicists,

chemists and engineers also find themselves working in materials

science.

The overlap between physics and materials science has led to the offshoot field of

materials physics, which is concerned with the physical properties of materials. The approach is generally more macroscopic and applied than in

condensed matter physics. See

important publications in materials physics for more details on this field of study.

The field of materials science and engineering is important both

from a scientific perspective, as well as from an engineering one. When

discovering new materials, one encounters new phenomena that may not

have been observed before. Hence, there is a lot of science to be

discovered when working with materials. Materials science also provides a

test for theories in condensed matter physics.

Materials are of the utmost importance for engineers, as the

usage of the appropriate materials is crucial when designing systems. As

a result, materials science is an increasingly important part of an

engineer's education.

Emerging technologies in materials science

| Aerogel

|

Hypothetical, experiments, diffusion, early uses[15]

|

Traditional insulation, glass

|

Improved insulation, insulative glass if it can be made clear,

sleeves for oil pipelines, aerospace, high-heat & extreme cold

applications

|

|

| Amorphous metal

|

Experiments

|

Kevlar

|

Armor

|

|

| Conductive polymers

|

Research, experiments, prototypes

|

Conductors

|

Lighter and cheaper wires, antistatic materials, organic solar cells

|

|

| Femtotechnology, picotechnology

|

Hypothetical

|

Present nuclear

|

New materials; nuclear weapons, power

|

|

| Fullerene

|

Experiments, diffusion

|

Synthetic diamond and carbon nanotubes (e.g., Buckypaper)

|

Programmable matter

|

|

| Graphene

|

Hypothetical, experiments, diffusion, early uses[16][17]

|

Silicon-based integrated circuit

|

Components with higher strength to weight ratios, transistors that

operate at higher frequency, lower cost of display screens in mobile

devices, storing hydrogen for fuel cell powered cars, filtration

systems, longer-lasting and faster-charging batteries, sensors to

diagnose diseases[18]

|

Potential applications of graphene

|

| High-temperature superconductivity

|

Cryogenic receiver front-end (CRFE) RF and microwave filter systems for mobile phone base stations; prototypes in dry ice; Hypothetical and experiments for higher temperatures[19]

|

Copper wire, semiconductor integral circuits

|

No loss conductors, frictionless bearings, magnetic levitation, lossless high-capacity accumulators, electric cars, heat-free integral circuits and processors

|

|

| LiTraCon

|

Experiments, already used to make Europe Gate

|

Glass

|

Building skyscrapers, towers, and sculptures like Europe Gate

|

|

| Metamaterials

|

Hypothetical, experiments, diffusion[20]

|

Classical optics

|

Microscopes, cameras, metamaterial cloaking, cloaking devices

|

|

| Metal foam

|

Research, commercialization

|

Hulls

|

Space colonies, floating cities

|

|

| Multi-function structures[21]

|

Hypothetical, experiments, some prototypes, few commercial

|

Composite materials mostly

|

Wide range, e.g., self health monitoring, self healing material, morphing, ...

|

|

| Nanomaterials: carbon nanotubes

|

Hypothetical, experiments, diffusion, early uses[22][23]

|

Structural steel and aluminium

|

Stronger, lighter materials, space elevator

|

Potential applications of carbon nanotubes, carbon fiber

|

| Programmable matter

|

Hypothetical, experiments[24][25]

|

Coatings, catalysts

|

Wide range, e.g., claytronics, synthetic biology

|

|

| Quantum dots

|

Research, experiments, prototypes[26]

|

LCD, LED

|

Quantum dot laser,

future use as programmable matter in display technologies (TV,

projection), optical data communications (high-speed data transmission),

medicine (laser scalpel)

|

|

| Silicene

|

Hypothetical, research

|

Field-effect transistors

|

|

|

| Superalloy

|

Research, diffusion

|

Aluminum, titanium, composite materials

|

Aircraft jet engines

|

|

| Synthetic diamond

|

early uses (drill bits, jewelry)

|

Silicon transistors

|

Electronics

|

|