Example of a textual analysis program being used to study a novel, with Jane Austen's Pride and Prejudice in Voyant Tools

Digital humanities (DH) is an area of scholarly activity at the intersection of computing or digital technologies and the disciplines of the humanities. It includes the systematic use of digital resources in the humanities, as well as the reflection on their application.

DH can be defined as new ways of doing scholarship that involve

collaborative, transdisciplinary, and computationally engaged research,

teaching, and publishing.

It brings digital tools and methods to the study of the humanities with

the recognition that the printed word is no longer the main medium for

knowledge production and distribution.

By producing and using new applications and techniques, DH makes

new kinds of teaching and research possible, while at the same time

studying and critiquing how these impact cultural heritage and digital

culture.

Thus, a distinctive feature of DH is its cultivation of a two-way

relationship between the humanities and the digital: the field both

employs technology in the pursuit of humanities research and subjects

technology to humanistic questioning and interrogation, often

simultaneously.

Definition

The

definition of the digital humanities is being continually formulated by

scholars and practitioners. Since the field is constantly growing and

changing, specific definitions can quickly become outdated or

unnecessarily limit future potential. The second volume of Debates in the Digital Humanities

(2016) acknowledges the difficulty in defining the field: "Along with

the digital archives, quantitative analyses, and tool-building projects

that once characterized the field, DH now encompasses a wide range of

methods and practices: visualizations of large image sets, 3D modeling

of historical artifacts, 'born digital' dissertations, hashtag activism and the analysis thereof, alternate reality games,

mobile makerspaces, and more. In what has been called 'big tent' DH, it

can at times be difficult to determine with any specificity what,

precisely, digital humanities work entails."

Historically, the digital humanities developed out of humanities

computing and has become associated with other fields, such as

humanistic computing, social computing, and media studies. In concrete

terms, the digital humanities embraces a variety of topics, from

curating online collections of primary sources (primarily textual) to

the data mining of large cultural data sets to topic modeling. Digital humanities incorporates both digitized (remediated) and born-digital materials and combines the methodologies from traditional humanities disciplines (such as history, philosophy, linguistics, literature, art, archaeology, music, and cultural studies) and social sciences, with tools provided by computing (such as hypertext, hypermedia, data visualisation, information retrieval, data mining, statistics, text mining, digital mapping), and digital publishing. Related subfields of digital humanities have emerged like software studies, platform studies, and critical code studies. Fields that parallel the digital humanities include new media studies and information science as well as media theory of composition, game studies, particularly in areas related to digital humanities project design and production, and cultural analytics.

The Digital Humanities Stack (from Berry and Fagerjord, Digital Humanities: Knowledge and Critique in a Digital Age)

Berry and Fagerjord have suggested that a way to reconceptualise

digital humanities could be through a "digital humanities stack". They

argue that "this type of diagram is common in computation and computer

science to show how technologies are ‘stacked’ on top of each other in

increasing levels of abstraction. Here, [they] use the method in a more

illustrative and creative sense of showing the range of activities,

practices, skills, technologies and structures that could be said to

make up the digital humanities, with the aim of providing a high-level

map."

Indeed, the "diagram can be read as the bottom levels indicating some

of the fundamental elements of the digital humanities stack, such as

computational thinking and knowledge representation, and then other

elements that later build on these. "

History

Digital

humanities descends from the field of humanities computing, whose

origins reach back to the 1930s and1940s in the pioneering work of

English professor Josephine Miles and Jesuit scholar Roberto Busa and the women they employed. In collaboration with IBM, they created a computer-generated concordance to Thomas Aquinas' writings known as the Index Thomisticus.

Other scholars began using mainframe computers to automate tasks like

word-searching, sorting, and counting, which was much faster than

processing information from texts with handwritten or typed index cards.

In the decades which followed archaeologists, classicists, historians,

literary scholars, and a broad array of humanities researchers in other

disciplines applied emerging computational methods to transform

humanities scholarship.

As Tara McPherson has pointed out, the digital humanities also

inherit practices and perspectives developed through many artistic and

theoretical engagements with electronic screen culture beginning the

late 1960s and 1970s. These range from research developed by

organizations such as SIGGRAPH to creations by artists such as Charles and Ray Eames and the members of E.A.T.

(Experiments in Art and Technology). The Eames and E.A.T. explored

nascent computer culture and intermediality in creative works that

dovetailed technological innovation with art.

The first specialized journal in the digital humanities was Computers and the Humanities,

which debuted in 1966. The Association for Literary and Linguistic

Computing (ALLC) and the Association for Computers and the Humanities

(ACH) were then founded in 1977 and 1978, respectively.

Soon, there was a need for a standardized protocol for tagging digital texts, and the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) was developed. The TEI project was launched in 1987 and published the first full version of the TEI Guidelines in May 1994. TEI helped shape the field of electronic textual scholarship and led to Extensible Markup Language

(XML), which is a tag scheme for digital editing. Researchers also

began experimenting with databases and hypertextual editing, which are

structured around links and nodes, as opposed to the standard linear

convention of print. In the nineties, major digital text and image archives emerged at centers of humanities computing in the U.S. (e.g. the Women Writers Project, the Rossetti Archive, and The William Blake Archive), which demonstrated the sophistication and robustness of text-encoding for literature.

The advent of personal computing and the World Wide Web meant that

Digital Humanities work could become less centered on text and more on

design. The multimedia nature of the internet has allowed Digital

Humanities work to incorporate audio, video, and other components in

addition to text.

The terminological change from "humanities computing" to "digital humanities" has been attributed to John Unsworth, Susan Schreibman, and Ray Siemens who, as editors of the anthology A Companion to Digital Humanities (2004), tried to prevent the field from being viewed as "mere digitization."

Consequently, the hybrid term has created an overlap between fields

like rhetoric and composition, which use "the methods of contemporary

humanities in studying digital objects," and digital humanities, which uses "digital technology in studying traditional humanities objects".

The use of computational systems and the study of computational media

within the arts and humanities more generally has been termed the

'computational turn'.

In 2006 the National Endowment for the Humanities

(NEH) launched the Digital Humanities Initiative (renamed Office of

Digital Humanities in 2008), which made widespread adoption of the term

"digital humanities" all but irreversible in the United States.

Digital humanities emerged from its former niche status and became "big news" at the 2009 MLA convention in Philadelphia, where digital humanists made "some of the liveliest and most visible contributions" and had their field hailed as "the first 'next big thing' in a long time."

Values and methods

Although digital humanities projects and initiatives are diverse, they often reflect common values and methods. These can help in understanding this hard-to-define field.

Values

- Critical & Theoretical

- Iterative & Experimental

- Collaborative & Distributed

- Multimodal & Performative

- Open & Accessible

Methods

- Enhanced Critical Curation

- Augmented Editions and Fluid Textuality

- Scale: The Law of Large Numbers

- Distant/Close, Macro/Micro, Surface/Depth

- Cultural Analytics, Aggregation, and Data-Mining

- Visualization and Data Design

- Locative Investigation and Thick Mapping

- The Animated Archive

- Distributed Knowledge Production and Performative Access

- Humanities Gaming

- Code, Software, and Platform Studies

- Database Documentaries

- Repurposable Content and Remix Culture

- Pervasive Infrastructure

- Ubiquitous Scholarship.

In keeping with the value of being open and accessible, many digital humanities projects and journals are open access and/or under Creative Commons licensing, showing the field's "commitment to open standards and open source."

Open access is designed to enable anyone with an internet-enabled

device and internet connection to view a website or read an article

without having to pay, as well as share content with the appropriate

permissions.

Digital humanities scholars use computational methods either to

answer existing research questions or to challenge existing theoretical

paradigms, generating new questions and pioneering new approaches. One

goal is to systematically integrate computer technology into the

activities of humanities scholars, as is done in contemporary empirical social sciences.

Yet despite the significant trend in digital humanities towards

networked and multimodal forms of knowledge, a substantial amount of

digital humanities focuses on documents and text in ways that

differentiate the field's work from digital research in media studies, information studies, communication studies, and sociology. Another goal of digital humanities is to create scholarship that transcends textual sources. This includes the integration of multimedia, metadata, and dynamic environments (see The Valley of the Shadow project at the University of Virginia, the Vectors Journal of Culture and Technology in a Dynamic Vernacular at University of Southern California, or Digital Pioneers projects at Harvard).

A growing number of researchers in digital humanities are using

computational methods for the analysis of large cultural data sets such

as the Google Books corpus.

Examples of such projects were highlighted by the Humanities High

Performance Computing competition sponsored by the Office of Digital

Humanities in 2008, and also by the Digging Into Data challenge organized in 2009 and 2011 by NEH in collaboration with NSF, and in partnership with JISC in the UK, and SSHRC in Canada.

In addition to books, historical newspapers can also be analyzed with

big data methods. The analysis of vast quantities of historical

newspaper content has showed how periodic structures can be

automatically discovered, and a similar analysis was performed on social

media. As part of the big data revolution, Gender bias, readability, content similarity, reader preferences, and even mood have been analyzed based on text mining methods over millions of documents and historical documents written in literary Chinese.

Digital humanities is also involved in the creation of software,

providing "environments and tools for producing, curating, and

interacting with knowledge that is 'born digital' and lives in various

digital contexts." In this context, the field is sometimes known as computational humanities.

Narrative network of US Elections 2012

Tools

Digital humanities scholars use a variety of digital tools for their

research, which may take place in an environment as small as a mobile

device or as large as a virtual reality

lab. Environments for "creating, publishing and working with digital

scholarship include everything from personal equipment to institutes and

software to cyberspace."

Some scholars use advanced programming languages and databases, while

others use less complex tools, depending on their needs. DiRT (Digital

Research Tools Directory) offers a registry of digital research tools for scholars. TAPoR (Text Analysis Portal for Research) is a gateway to text analysis and retrieval tools. An accessible, free example of an online textual analysis program is Voyant Tools,

which only requires the user to copy and paste either a body of text or

a URL and then click the 'reveal' button to run the program. There is

also an online list

of online or downloadable Digital Humanities tools that are largely

free, aimed toward helping students and others who lack access to

funding or institutional servers. Free, open source web publishing

platforms like WordPress and Omeka are also popular tools.

Example of a visualization tool used to study poetry in a new way with Poemage

Projects

Digital

humanities projects are more likely than traditional humanities work to

involve a team or a lab, which may be composed of faculty, staff,

graduate or undergraduate students, information technology specialists,

and partners in galleries, libraries, archives, and museums. Credit and

authorship are often given to multiple people to reflect this

collaborative nature, which is different from the sole authorship model

in the traditional humanities (and more like the natural sciences).

There are thousands of digital humanities projects, ranging from

small-scale ones with limited or no funding to large-scale ones with

multi-year financial support. Some are continually updated while others

may not be due to loss of support or interest, though they may still

remain online in either a beta version or a finished form. The following are a few examples of the variety of projects in the field:

Digital archives

The Women Writers Project

(begun in 1988) is a long-term research project to make pre-Victorian

women writers more accessible through an electronic collection of rare

texts. The Walt Whitman Archive (begun in the 1990s) sought to create a hypertext and scholarly edition of Whitman’s

works and now includes photographs, sounds, and the only comprehensive

current bibliography of Whitman criticism. The Emily Dickinson Archive

(begun in 2013) is a collection of high-resolution images of Dickinson’s poetry manuscripts as well as a searchable lexicon of over 9,000 words that appear in the poems.

Example of network analysis as an archival tool at the League of Nations.

The Slave Societies Digital Archive (formerly Ecclesiastical and Secular Sources for Slave Societies), directed by Jane Landers

and hosted at Vanderbilt University, preserves endangered

ecclesiastical and secular documents related to Africans and

African-descended peoples in slave societies. This Digital Archive

currently holds 500,000 unique images, dating from the 16th to the 20th

centuries, and documents the history of between 6 and 8 million

individuals. They are the most extensive serial records for the history

of Africans in the Atlantic World and also include valuable information

on the indigenous, European, and Asian populations who lived alongside

them.

The involvement of librarians and archivists plays an important

part in digital humanities projects because of the recent expansion of

their role so that it now covers digital curation,

which is critical in the preservation, promotion, and access to digital

collections, as well as the application of scholarly orientation to

digital humanities projects.

A specific example involves the case of initiatives where archivists

help scholars and academics build their projects through their

experience in evaluating, implementing, and customizing metadata schemas

for library collections.

The initiatives at the National Autonomous University of Mexico

is another example of a digital humanities project. These include the

digitization of 17th-century manuscripts, an electronic corpus of

Mexican history from the 16th to 19th century, and the visualization of

pre-Hispanic archaeological sites in 3-D.

Cultural analytics

"Cultural

analytics" refers to the use of computational method for exploration

and analysis of large visual collections and also contemporary digital

media. The concept was developed in 2005 by Lev Manovich

who then established the Cultural Analytics Lab in 2007 at Qualcomm

Institute at California Institute for Telecommunication and Information

(Calit2). The lab has been using methods from the field of computer

science called Computer Vision many types of both historical and

contemporary visual media—for example, all covers of Time magazine published between 1923 and 2009, 20,000 historical art photographs from the collection in Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York, one million pages from Manga books, and 16 million images shared on Instagram in 17 global cities.

Cultural analytics also includes using methods from media design and

data visualization to create interactive visual interfaces for

exploration of large visual collections e.g., Selfiecity and On

Broadway.

Cultural Analytics research is also addressing a number of

theoretical questions. How can we "observe" giant cultural universes of

both user-generated and professional media content created today,

without reducing them to averages, outliers, or pre-existing categories?

How can work with large cultural data help us question our stereotypes

and assumptions about cultures? What new theoretical cultural concepts

and models are required for studying global digital culture with its new

mega-scale, speed, and connectivity?

The term “cultural analytics” (or “culture analytics”) is now

used by many other researchers, as exemplified by two academic

symposiums, a four-month long research program at UCLA that brought together 120 leading researchers from university and industry labs, an academic peer-review Journal of Cultural Analytics: CA established in 2016, and academic job listings.

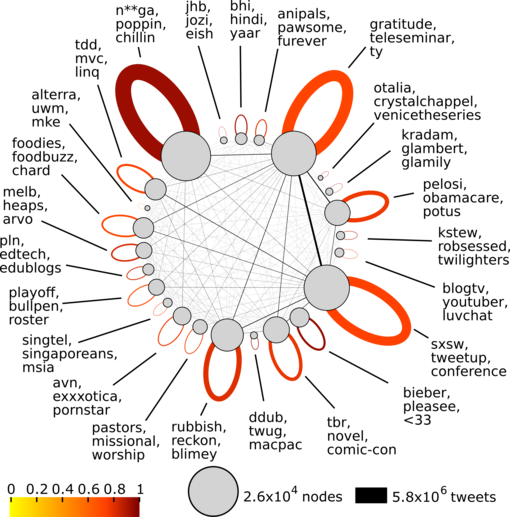

Textual mining, analysis, and visualization

WordHoard (begun in 2004) is a free application that enables scholarly

but non-technical users to read and analyze, in new ways, deeply-tagged

texts, including the canon of Early Greek epic, Chaucer, Shakespeare, and Spenser. The Republic of Letters (begun in 2008)

seeks to visualize the social network of Enlightenment writers through

an interactive map and visualization tools. Network analysis and data

visualization is also used for reflections on the field itself –

researchers may produce network maps of social media interactions or

infographics from data on digital humanities scholars and projects.

Network analysis: graph of Digital Humanities Twitter users

Analysis of macroscopic trends in cultural change

Culturomics is a form of computational lexicology that studies human behavior and cultural trends through the quantitative analysis of digitized texts. Researchers data mine large digital archives to investigate cultural phenomena reflected in language and word usage. The term is an American neologism first described in a 2010 Science article called Quantitative Analysis of Culture Using Millions of Digitized Books, co-authored by Harvard researchers Jean-Baptiste Michel and Erez Lieberman Aiden.

A 2017 study published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America compared the trajectory of n-grams over time in both digitised books from the 2010 Science article

with those found in a large corpus of regional newspapers from the

United Kingdom over the course of 150 years. The study further went on

to use more advanced Natural language processing

techniques to discover macroscopic trends in history and culture,

including gender bias, geographical focus, technology, and politics,

along with accurate dates for specific events.

Online publishing

The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

(begun in 1995) is a dynamic reference work of terms, concepts, and

people from philosophy maintained by scholars in the field. MLA Commons offers an open peer-review site (where anyone can comment) for their ongoing curated collection of teaching artifacts in Digital Pedagogy in the Humanities: Concepts, Models, and Experiments (2016). The Debates in the Digital Humanities

platform contains volumes of the open-access book of the same title

(2012 and 2016 editions) and allows readers to interact with material by

marking sentences as interesting or adding terms to a crowdsourced

index.

Criticism

Lauren F. Klein and Matthew K. Gold have identified a range of

criticisms in the digital humanities field: "'a lack of attention to

issues of race, class, gender, and sexuality; a preference for

research-driven projects over pedagogical ones; an absence of political

commitment; an inadequate level of diversity among its practitioners; an

inability to address texts under copyright; and an institutional

concentration in well-funded research universities".

Similarly Berry and Fagerjord have argued that a digital humanities

should "focus on the need to think critically about the implications of

computational imaginaries, and raise some questions in this regard. This

is also to foreground the importance of the politics and norms that are

embedded in digital technology, algorithms and software. We need to

explore how to negotiate between close and distant readings of texts and

how micro-analysis and macro-analysis can be usefully reconciled in

humanist work."

Alan Liu has argued, "while digital humanists develop tools, data, and

metadata critically, therefore (e.g., debating the ‘ordered hierarchy of

content objects’ principle; disputing whether computation is best used

for truth finding or, as Lisa Samuels and Jerome McGann put it,

‘deformance’; and so on) rarely do they extend their critique to the

full register of society, economics, politics, or culture." Some of these concerns have given rise to the emergent subfield of Critical Digital Humanities (CDH):

Some key questions include: how do we make the invisible become visible in the study of software? How is knowledge transformed when mediated through code and software? What are the critical approaches to Big Data, visualization, digital methods, etc.? How does computation create new disciplinary boundaries and gate-keeping functions? What are the new hegemonic representations of the digital – ‘geons’, ‘pixels’, ‘waves’, visualization, visual rhetorics, etc.? How do media changes create epistemic changes, and how can we look behind the ‘screen essentialism’ of computational interfaces? Here we might also reflect on the way in which the practice of making- visible also entails the making-invisible – computation involves making choices about what is to be captured.

Negative publicity

Klein

and Gold note that many appearances of the digital humanities in public

media are often in a critical fashion. Armand Leroi, writing in The New York Times,

discusses the contrast between the algorithmic analysis of themes in

literary texts and the work of Harold Bloom, who qualitatively and

phenomenologically analyzes the themes of literature over time. Leroi

questions whether or not the digital humanities can provide a truly

robust analysis of literature and social phenomenon or offer a novel

alternative perspective on them. The literary theorist Stanley Fish

claims that the digital humanities pursue a revolutionary agenda and

thereby undermine the conventional standards of "pre-eminence, authority

and disciplinary power."

However, digital humanities scholars note that "Digital Humanities is

an extension of traditional knowledge skills and methods, not a

replacement for them. Its distinctive contributions do not obliterate

the insights of the past, but add and supplement the humanities'

long-standing commitment to scholarly interpretation, informed research,

structured argument, and dialogue within communities of practice".

Some have hailed the digital humanities as a solution to the

apparent problems within the humanities, namely a decline in funding, a

repeat of debates, and a fading set of theoretical claims and

methodological arguments. Adam Kirsch, writing in the New Republic, calls this the "False Promise" of the digital humanities.

While the rest of humanities and many social science departments are

seeing a decline in funding or prestige, the digital humanities has been

seeing increasing funding and prestige. Burdened with the problems of

novelty, the digital humanities is discussed as either a revolutionary

alternative to the humanities as it is usually conceived or as simply

new wine in old bottles. Kirsch believes that digital humanities

practitioners suffer from problems of being marketers rather than

scholars, who attest to the grand capacity of their research more than

actually performing new analysis and when they do so, only performing

trivial parlor tricks of research. This form of criticism has been

repeated by others, such as in Carl Staumshein, writing in Inside Higher Education, who calls it a "Digital Humanities Bubble".

Later in the same publication, Straumshein alleges that the digital

humanities is a 'Corporatist Restructuring' of the Humanities.

Some see the alliance of the digital humanities with business to be a

positive turn that causes the business world to pay more attention, thus

bringing needed funding and attention to the humanities.

If it were not burdened by the title of digital humanities, it could

escape the allegations that it is elitist and unfairly funded.

Black box

There

has also been critique of the use of digital humanities tools by

scholars who do not fully understand what happens to the data they input

and place too much trust in the "black box" of software that cannot be

sufficiently examined for errors. Johanna Drucker, a professor at UCLA

Department of Information Studies, has criticized the "epistemological

fallacies" prevalent in popular visualization tools and technologies

(such as Google's

n-gram graph) used by digital humanities scholars and the general

public, calling some network diagramming and topic modeling tools "just

too crude for humanistic work."

The lack of transparency in these programs obscures the subjective

nature of the data and its processing, she argues, as these programs

"generate standard diagrams based on conventional algorithms for screen

display...mak[ing] it very difficult for the semantics of the data

processing to be made evident."

Diversity

There

has also been some recent controversy among practitioners of digital

humanities around the role that race and/or identity politics plays.

Tara McPherson attributes some of the lack of racial diversity in

digital humanities to the modality of UNIX and computers themselves.

An open thread on DHpoco.org recently garnered well over 100 comments

on the issue of race in digital humanities, with scholars arguing about

the amount that racial (and other) biases affect the tools and texts

available for digital humanities research.

McPherson posits that there needs to be an understanding and theorizing

of the implications of digital technology and race, even when the

subject for analysis appears not to be about race.

Amy E. Earhart criticizes what has become the new digital humanities "canon" in the shift from websites using simple HTML to the usage of the TEI and visuals in textual recovery projects.

Works that has been previously lost or excluded were afforded a new

home on the internet, but much of the same marginalizing practices found

in traditional humanities also took place digitally. According to

Earhart, there is a "need to examine the canon that we, as digital

humanists, are constructing, a canon that skews toward traditional texts

and excludes crucial work by women, people of color, and the LGBTQ

community."

Issues of access

Practitioners

in digital humanities are also failing to meet the needs of users with

disabilities. George H. Williams argues that universal design is

imperative for practitioners to increase usability because "many of the

otherwise most valuable digital resources are useless for people who

are—for example—deaf or hard of hearing, as well as for people who are

blind, have low vision, or have difficulty distinguishing particular

colors."

In order to provide accessibility successfully, and productive

universal design, it is important to understand why and how users with

disabilities are using the digital resources while remembering that all

users approach their informational needs differently.

Cultural criticism

Digital

humanities have been criticized for not only ignoring traditional

questions of lineage and history in the humanities, but lacking the

fundamental cultural criticism that defines the humanities. However, it

remains to be seen whether or not the humanities have to be tied to

cultural criticism, per se, in order to be the humanities. The sciences

might imagine the Digital Humanities as a welcome improvement over the

non-quantitative methods of the humanities and social sciences.

Difficulty of evaluation

As

the field matures, there has been a recognition that the standard model

of academic peer-review of work may not be adequate for digital

humanities projects, which often involve website components, databases,

and other non-print objects. Evaluation of quality and impact thus

require a combination of old and new methods of peer review. One response has been the creation of the DHCommons Journal.

This accepts non-traditional submissions, especially mid-stage digital

projects, and provides an innovative model of peer review more suited

for the multimedia, transdisciplinary, and milestone-driven nature of

Digital Humanities projects. Other professional humanities

organizations, such as the American Historical Association and the Modern Language Association, have developed guidelines for evaluating academic digital scholarship.

Lack of focus on pedagogy

The 2012 edition of Debates in the Digital Humanities

recognized the fact that pedagogy was the “neglected ‘stepchild’ of DH”

and included an entire section on teaching the digital humanities.

Part of the reason is that grants in the humanities are geared more

toward research with quantifiable results rather than teaching

innovations, which are harder to measure. In recognition of a need for more scholarship on the area of teaching, Digital Humanities Pedagogy

was published and offered case studies and strategies to address how to

teach digital humanities methods in various disciplines.

Organizations

The Alliance of Digital Humanities Organizations

(ADHO) is an umbrella organization that supports digital research and

teaching as a consultative and advisory force for its constituent

organizations. Its governance was approved in 2005 and it has overseen

the annual Digital Humanities conference since 2006. The current members of ADHO are:

- Australasian Association for Digital Humanities (aaDH)

- Association for Computers and the Humanities (ACH)

- Canadian Society for Digital Humanities / Société canadienne des humanités numériques (CSDH/SCHN)

- centerNet, an international network of digital humanities centers

- The European Association for Digital Humanities (EADH)

- Japanese Association for Digital Humanities (JADH)

- Humanistica, L'association francophone des humanités numériques/digitales (Humanistica)

ADHO funds a number of projects such as the Digital Humanities Quarterly journal and the Digital Scholarship in the Humanities (DSH) journal, supports the Text Encoding Initiative, and sponsors workshops and conferences, as well as funding small projects, awards, and bursaries.

HASTAC

(Humanities, Arts, Science, and Technology Alliance and Collaboratory)

is a free and open access virtual, interdisciplinary community focused

on changing teaching and learning through the sharing of news, tools,

methods, and pedagogy, including digital humanities scholarship. It is reputed to be the world's first and oldest academic social network.

Centers and institutes

- Department of Digital Humanities (King's College London, UK)

- Humanities Advanced Technology and Information Institute (University of Glasgow, Scotland)

- Sussex Humanities Lab (University of Sussex, UK)

- Humlab, Umeå University (Sweden)

- Digital Humanities Summer Institute (DHSI) (University of Victoria, Canada)

- Forensic Computational Geometry Laboratory (FCGL)[95] (IWR, Heidelberg University, Germany)

- Heidelberg Centre for Digital Humanities (Heidelberg University, Germany)

- The European Summer University in Digital Humanities (Leipzig University, Germany)

- Cultural Analytics Lab (The Graduate Center, City University of New York, USA, and Qualcomm Institute, USA)

- Center for Digital Research in the Humanities (University of Nebraska-Lincoln, USA)

- Institute for Advanced Technology in the Humanities (University of Virginia, USA)

- Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities (University of Maryland, USA)

- Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media (George Mason University, Virginia, USA)

- The Walter J. Ong, S.J. Center for Digital Humanities (Saint Louis University, St. Louis, MO, USA

- UCL Centre for Digital Humanities (University College London, UK)

- Center for Public History and Digital Humanities (Cleveland State University, USA)

- Center for Digital Scholarship and Curation (Washington State University, USA)

- Scholars' Lab (University of Virginia, USA)

- Centre for Digital Humanities Research (Australian National University, AU)

- Helsinki Centre for Digital Humanities (HELDIG) (University of Helsinki, Finland)

- Laboratory for digital cultures and humanities of the University of Lausanne (LaDHUL) (University of Lausanne, Switzerland)

- Centre for Information-Modeling, Austrian Centre for Digital Humanities (ZIM-ACDH) (University of Graz, Austria)

- mainzed, Mainz Centre for Digitality in the Humanities and Cultural Studies (Mainz, Germany)

Conferences

- Digital Humanities conference

- THATCamp

- Text Encoding Initiative (TEI) conference

Journals and publications

- Digital Humanities Quarterly (DHQ)

- DHCommons

- Digital Literary Studies

- Digital Medievalist

- Digital Scholarship in the Humanities (DSH) (formerly Literary and Linguistic Computing)

- Digital Studies / Le champ numérique (DS/CN)

- Humanités numériques (Humanistica)

- Journal of Digital Archives and Digital Humanities

- Journal of Digital and Media Literacy

- Journal of Digital Humanities (JDH)

- Journal of Interactive Technology and Pedagogy

- Journal of the Japanese Association for Digital Humanities (JJADH)

- Journal of the Text Encoding Initiative

- Kairos

- Southern Spaces

- Umanistica Digitale (AIUCD)