Full-disc view of Jupiter in natural color in April 2014

| |||||||||||||||

| Designations | |||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈdʒuːpɪtər/ | ||||||||||||||

| Adjectives | Jovian | ||||||||||||||

| Orbital characteristics | |||||||||||||||

| Epoch J2000 | |||||||||||||||

| Aphelion | 816.62 million km (5.4588 AU) | ||||||||||||||

| Perihelion | 740.52 million km (4.9501 AU) | ||||||||||||||

| 778.57 million km (5.2044 AU) | |||||||||||||||

| Eccentricity | 0.0489 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| 398.88 d | |||||||||||||||

Average orbital speed

| 13.07 km/s (8.12 mi/s) | ||||||||||||||

| 20.020° | |||||||||||||||

| Inclination |

| ||||||||||||||

| 100.464° | |||||||||||||||

| 273.867° | |||||||||||||||

| Known satellites | 79 (as of 2018) | ||||||||||||||

| Physical characteristics | |||||||||||||||

Mean radius

| 69,911 km (43,441 mi) | ||||||||||||||

Equatorial radius

|

| ||||||||||||||

Polar radius

|

| ||||||||||||||

| Flattening | 0.06487 | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| Volume |

| ||||||||||||||

| Mass |

| ||||||||||||||

Mean density

| 1,326 kg/m3 (2,235 lb/cu yd) | ||||||||||||||

| 24.79 m/s2 (81.3 ft/s2) 2.528 g | |||||||||||||||

| 0.254 I/MR2 (estimate) | |||||||||||||||

| 59.5 km/s (37.0 mi/s) | |||||||||||||||

Sidereal rotation period

| 9.925 hours (9 h 55 m 30 s) | ||||||||||||||

Equatorial rotation velocity

| 12.6 km/s (7.8 mi/s; 45,000 km/h) | ||||||||||||||

| 3.13° (to orbit) | |||||||||||||||

North pole right ascension

| 268.057°; 17h 52m 14s | ||||||||||||||

North pole declination

| 64.495° | ||||||||||||||

| Albedo | 0.503 (Bond) 0.538 (geometric) | ||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||

| −2.94 to −1.66 | |||||||||||||||

| 29.8″ to 50.1″ | |||||||||||||||

| Atmosphere | |||||||||||||||

Surface pressure

| 20–200 kPa; 70 kPa | ||||||||||||||

| 27 km (17 mi) | |||||||||||||||

| Composition by volume | by volume:

| ||||||||||||||

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the largest in the Solar System. It is a giant planet with a mass one-thousandth that of the Sun, but two-and-a-half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined. Jupiter and Saturn are gas giants; the other two giant planets, Uranus and Neptune, are ice giants. Jupiter has been known to astronomers since antiquity. It is named after the Roman god Jupiter. When viewed from Earth, Jupiter can reach an apparent magnitude of −2.94, bright enough for its reflected light to cast shadows, and making it on average the third-brightest natural object in the night sky after the Moon and Venus.

Jupiter is primarily composed of hydrogen with a quarter of its mass being helium, though helium comprises only about a tenth of the number of molecules. It may also have a rocky core of heavier elements, but like the other giant planets, Jupiter lacks a well-defined solid surface. Because of its rapid rotation, the planet's shape is that of an oblate spheroid (it has a slight but noticeable bulge around the equator). The outer atmosphere is visibly segregated into several bands at different latitudes, resulting in turbulence and storms along their interacting boundaries. A prominent result is the Great Red Spot, a giant storm that is known to have existed since at least the 17th century when it was first seen by telescope. Surrounding Jupiter is a faint planetary ring system and a powerful magnetosphere. Jupiter has 79 known moons, including the four large Galilean moons discovered by Galileo Galilei in 1610. Ganymede, the largest of these, has a diameter greater than that of the planet Mercury.

Jupiter has been explored on several occasions by robotic spacecraft, most notably during the early Pioneer and Voyager flyby missions and later by the Galileo orbiter. In late February 2007, Jupiter was visited by the New Horizons probe, which used Jupiter's gravity to increase its speed and bend its trajectory en route to Pluto. The latest probe to visit the planet is Juno, which entered into orbit around Jupiter on July 4, 2016. Future targets for exploration in the Jupiter system include the probable ice-covered liquid ocean of its moon Europa.

Formation and migration

Astronomers have discovered nearly 500 planetary systems with multiple planets. Regularly these systems include a few planets with masses several times greater than Earth's (super-Earths), orbiting closer to their star than Mercury is to the Sun, and sometimes also Jupiter-mass gas giants close to their star.Earth and its neighbor planets may have formed from fragments of planets after collisions with Jupiter destroyed those super-Earths near the Sun. As Jupiter came toward the inner Solar System, in what theorists call the grand tack hypothesis, gravitational tugs and pulls occurred causing a series of collisions between the super-Earths as their orbits began to overlap.

Jupiter moving out of the inner Solar System would have allowed the formation of inner planets, including Earth.

Physical characteristics

Jupiter is composed primarily of gaseous and liquid matter. It is the largest of the four giant planets in the Solar System and hence its largest planet. It has a diameter of 142,984 km (88,846 mi) at its equator. The average density of Jupiter, 1.326 g/cm3, is the second highest of the giant planets, but lower than those of the four terrestrial planets.Composition

Jupiter's upper atmosphere is about 88–92% hydrogen and 8–12% helium by percent volume of gas molecules. A helium atom has about four times as much mass as a hydrogen atom, so the composition changes when described as the proportion of mass contributed by different atoms. Thus, Jupiter's atmosphere is approximately 75% hydrogen and 24% helium by mass, with the remaining one percent of the mass consisting of other elements. The atmosphere contains trace amounts of methane, water vapor, ammonia, and silicon-based compounds. There are also traces of carbon, ethane, hydrogen sulfide, neon, oxygen, phosphine, and sulfur. The outermost layer of the atmosphere contains crystals of frozen ammonia. The interior contains denser materials - by mass it is roughly 71% hydrogen, 24% helium, and 5% other elements. Through infrared and ultraviolet measurements, trace amounts of benzene and other hydrocarbons have also been found.The atmospheric proportions of hydrogen and helium are close to the theoretical composition of the primordial solar nebula. Neon in the upper atmosphere only consists of 20 parts per million by mass, which is about a tenth as abundant as in the Sun. Helium is also depleted to about 80% of the Sun's helium composition. This depletion is a result of precipitation of these elements into the interior of the planet.

Based on spectroscopy, Saturn is thought to be similar in composition to Jupiter, but the other giant planets Uranus and Neptune have relatively less hydrogen and helium and relatively more ices and are thus now termed ice giants.

Mass and size

Jupiter's diameter is one order of magnitude

smaller (×0.10045) than that of the Sun, and one order of magnitude

larger (×10.9733) than that of Earth. The Great Red Spot is roughly the

same size as Earth.

Jupiter's mass is 2.5 times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined—this is so massive that its barycenter with the Sun lies above the Sun's surface at 1.068 solar radii from the Sun's center.

Jupiter is much larger than Earth and considerably less dense: its

volume is that of about 1,321 Earths, but it is only 318 times as

massive. Jupiter's radius is about 1/10 the radius of the Sun, and its mass is 0.001 times the mass of the Sun, so the densities of the two bodies are similar. A "Jupiter mass" (MJ or MJup) is often used as a unit to describe masses of other objects, particularly extrasolar planets and brown dwarfs. So, for example, the extrasolar planet HD 209458 b has a mass of 0.69 MJ, while Kappa Andromedae b has a mass of 12.8 MJ.

Theoretical models indicate that if Jupiter had much more mass than it does at present, it would shrink. For small changes in mass, the radius would not change appreciably, and above about 500 M⊕ (1.6 Jupiter masses) the interior would become so much more compressed under the increased pressure that its volume would decrease

despite the increasing amount of matter. As a result, Jupiter is

thought to have about as large a diameter as a planet of its composition

and evolutionary history can achieve. The process of further shrinkage with increasing mass would continue until appreciable stellar ignition was achieved, as in high-mass brown dwarfs having around 50 Jupiter masses.

Although Jupiter would need to be about 75 times as massive to fuse hydrogen and become a star, the smallest red dwarf is only about 30 percent larger in radius than Jupiter.

Despite this, Jupiter still radiates more heat than it receives from

the Sun; the amount of heat produced inside it is similar to the total solar radiation it receives. This additional heat is generated by the Kelvin–Helmholtz mechanism through contraction. This process causes Jupiter to shrink by about 2 cm each year. When it was first formed, Jupiter was much hotter and was about twice its current diameter.

Internal structure

Jupiter is thought to consist of a dense core with a mixture of elements, a surrounding layer of liquid metallic hydrogen with some helium, and an outer layer predominantly of molecular hydrogen. Beyond this basic outline, there is still considerable uncertainty. The core is often described as rocky,

but its detailed composition is unknown, as are the properties of

materials at the temperatures and pressures of those depths (see below).

In 1997, the existence of the core was suggested by gravitational

measurements, indicating a mass of from 12 to 45 times that of Earth, or roughly 4%–14% of the total mass of Jupiter.

The presence of a core during at least part of Jupiter's history is

suggested by models of planetary formation that require the formation of

a rocky or icy core massive enough to collect its bulk of hydrogen and

helium from the protosolar nebula.

Assuming it did exist, it may have shrunk as convection currents of hot

liquid metallic hydrogen mixed with the molten core and carried its

contents to higher levels in the planetary interior. A core may now be

entirely absent, as gravitational measurements are not yet precise

enough to rule that possibility out entirely.

Animation of four images showing Jupiter in infrared light as seen by NASA's Infrared telescope facility on May 16, 2015

The uncertainty of the models is tied to the error margin in hitherto measured parameters: one of the rotational coefficients (J6) used to describe the planet's gravitational moment, Jupiter's equatorial radius, and its temperature at 1 bar pressure. The Juno mission, which arrived in July 2016, is expected to further constrain the values of these parameters for better models of the core.

The core region may be surrounded by dense metallic hydrogen, which extends outward to about 78% of the radius of the planet.

Rain-like droplets of helium and neon precipitate downward through this

layer, depleting the abundance of these elements in the upper

atmosphere. Rainfalls of diamonds have been suggested to occur on Jupiter, as well as on Saturn and ice giants Uranus and Neptune.

Above the layer of metallic hydrogen lies a transparent interior

atmosphere of hydrogen. At this depth, the pressure and temperature are

above hydrogen's critical pressure of 1.2858 MPa and critical temperature of only 32.938 K.

In this state, there are no distinct liquid and gas phases—hydrogen is

said to be in a supercritical fluid state. It is convenient to treat

hydrogen as gas in the upper layer extending downward from the cloud

layer to a depth of about 1,000 km,

and as liquid in deeper layers. Physically, there is no clear

boundary—the gas smoothly becomes hotter and denser as one descends.

The temperature and pressure inside Jupiter increase steadily toward the core, due to the Kelvin–Helmholtz mechanism. At the pressure level of 10 bars (1 MPa), the temperature is around 340 K (67 °C; 152 °F). At the phase transition

region where hydrogen—heated beyond its critical point—becomes

metallic, it is calculated the temperature is 10,000 K (9,700 °C;

17,500 °F) and the pressure is 200 GPa. The temperature at the core boundary is estimated to be 36,000 K (35,700 °C; 64,300 °F) and the interior pressure is roughly 3,000–4,500 GPa.

This cut-away illustrates a model of the interior of Jupiter, with a rocky core overlaid by a deep layer of liquid metallic hydrogen.

Atmosphere

Jupiter has the largest planetary atmosphere in the Solar System, spanning over 5,000 km (3,000 mi) in altitude.

Because Jupiter has no surface, the base of its atmosphere is usually

considered to be the point at which atmospheric pressure is equal to

100 kPa (1.0 bar).

Cloud layers

The movement of Jupiter's counter-rotating cloud bands. This looping animation maps the planet's exterior onto a cylindrical projection.

Jupiter is perpetually covered with clouds composed of ammonia crystals and possibly ammonium hydrosulfide. The clouds are located in the tropopause and are arranged into bands of different latitudes, known as tropical regions. These are sub-divided into lighter-hued zones and darker belts. The interactions of these conflicting circulation patterns cause storms and turbulence. Wind speeds of 100 m/s (360 km/h) are common in zonal jets.

The zones have been observed to vary in width, color and intensity from

year to year, but they have remained sufficiently stable for scientists

to give them identifying designations.

Jupiter clouds

(Juno; December 2017)

(Juno; December 2017)

The cloud layer is only about 50 km (31 mi) deep, and consists of at

least two decks of clouds: a thick lower deck and a thin clearer region.

There may also be a thin layer of water clouds underlying the ammonia layer. Supporting the idea of water clouds are the flashes of lightning

detected in the atmosphere of Jupiter. These electrical discharges can

be up to a thousand times as powerful as lightning on Earth.

The water clouds are assumed to generate thunderstorms in the same way

as terrestrial thunderstorms, driven by the heat rising from the

interior.

The orange and brown coloration in the clouds of Jupiter are

caused by upwelling compounds that change color when they are exposed to

ultraviolet light from the Sun. The exact makeup remains uncertain, but the substances are thought to be phosphorus, sulfur or possibly hydrocarbons. These colorful compounds, known as chromophores, mix with the warmer, lower deck of clouds. The zones are formed when rising convection cells form crystallizing ammonia that masks out these lower clouds from view.

Jupiter's low axial tilt means that the poles constantly receive less solar radiation than at the planet's equatorial region. Convection within the interior of the planet transports more energy to the poles, balancing out the temperatures at the cloud layer.

Great Red Spot and other vortices

Time-lapse sequence from the approach of Voyager 1,

showing the motion of atmospheric bands and circulation of the Great

Red Spot. Recorded over 32 days with one photograph taken every 10 hours

(once per Jovian day).

The best known feature of Jupiter is the Great Red Spot, a persistent anticyclonic storm that is larger than Earth, located 22° south of the equator. It is known to have been in existence since at least 1831, and possibly since 1665. Images by the Hubble Space Telescope have shown as many as two "red spots" adjacent to the Great Red Spot. The storm is large enough to be visible through Earth-based telescopes with an aperture of 12 cm or larger. The oval object rotates counterclockwise, with a period of about six days. The maximum altitude of this storm is about 8 km (5 mi) above the surrounding cloudtops.

Great Red Spot is decreasing in size (May 15, 2014).

The Great Red Spot is large enough to accommodate Earth within its boundaries. Mathematical models suggest that the storm is stable and may be a permanent feature of the planet.

However, it has significantly decreased in size since its discovery.

Initial observations in the late 1800s showed it to be approximately

41,000 km (25,500 mi) across. By the time of the Voyager flybys in 1979, the storm had a length of 23,300 km (14,500 mi) and a width of approximately 13,000 km (8,000 mi). Hubble

observations in 1995 showed it had decreased in size again to 20,950 km

(13,020 mi), and observations in 2009 showed the size to be 17,910 km

(11,130 mi). As of 2015, the storm was measured at approximately 16,500 by 10,940 km (10,250 by 6,800 mi), and is decreasing in length by about 930 km (580 mi) per year.

Storms such as this are common within the turbulent atmospheres of giant planets.

Jupiter also has white ovals and brown ovals, which are lesser unnamed

storms. White ovals tend to consist of relatively cool clouds within the

upper atmosphere. Brown ovals are warmer and located within the "normal

cloud layer". Such storms can last as little as a few hours or stretch

on for centuries.

Even before Voyager proved that the feature was a storm, there

was strong evidence that the spot could not be associated with any

deeper feature on the planet's surface, as the Spot rotates

differentially with respect to the rest of the atmosphere, sometimes

faster and sometimes more slowly.

In 2000, an atmospheric feature formed in the southern hemisphere

that is similar in appearance to the Great Red Spot, but smaller. This

was created when several smaller, white oval-shaped storms merged to

form a single feature—these three smaller white ovals were first

observed in 1938. The merged feature was named Oval BA, and has been nicknamed Red Spot Junior. It has since increased in intensity and changed color from white to red.

In April 2017, scientists reported the discovery of a "Great Cold

Spot" in Jupiter's thermosphere at its north pole that is 24,000 km

(15,000 mi) across, 12,000 km (7,500 mi) wide, and 200 °C (360 °F)

cooler than surrounding material. The feature was discovered by

researchers at the Very Large Telescope in Chile, who then searched archived data from the NASA Infrared Telescope Facility

between 1995 and 2000. They found that, while the Spot changes size,

shape and intensity over the short term, it has maintained its general

position in the atmosphere across more than 15 years of available data.

Scientists believe the Spot is a giant vortex similar to the Great Red

Spot and also appears to be quasi-stable like the vortices

in Earth's thermosphere. Interactions between charged particles

generated from Io and the planet's strong magnetic field likely resulted

in redistribution of heat flow, forming the Spot.

Magnetosphere

Infrared view of Jupiter's southern lights, taken by the Jovian Infrared Auroral Mapper

Jupiter's magnetic field is fourteen times as strong as that of Earth, ranging from 4.2 gauss (0.42 mT) at the equator to 10–14 gauss (1.0–1.4 mT) at the poles, making it the strongest in the Solar System (except for sunspots). This field is thought to be generated by eddy currents—swirling movements of conducting materials—within the liquid metallic hydrogen core. The volcanoes on the moon Io emit large amounts of sulfur dioxide forming a gas torus along the moon's orbit. The gas is ionized in the magnetosphere producing sulfur and oxygen ions. They, together with hydrogen ions originating from the atmosphere of Jupiter, form a plasma sheet

in Jupiter's equatorial plane. The plasma in the sheet co-rotates with

the planet causing deformation of the dipole magnetic field into that of

magnetodisk. Electrons within the plasma sheet generate a strong radio

signature that produces bursts in the range of 0.6–30 MHz.

At about 75 Jupiter radii from the planet, the interaction of the magnetosphere with the solar wind generates a bow shock. Surrounding Jupiter's magnetosphere is a magnetopause, located at the inner edge of a magnetosheath—a region between it and the bow shock. The solar wind interacts with these regions, elongating the magnetosphere on Jupiter's lee side

and extending it outward until it nearly reaches the orbit of Saturn.

The four largest moons of Jupiter all orbit within the magnetosphere,

which protects them from the solar wind.

The magnetosphere of Jupiter is responsible for intense episodes of radio emission

from the planet's polar regions. Volcanic activity on Jupiter's moon Io injects gas into Jupiter's magnetosphere, producing a torus

of particles about the planet. As Io moves through this torus, the

interaction generates Alfvén waves that carry ionized matter into the polar regions of Jupiter. As a result, radio waves are generated through a cyclotron maser mechanism,

and the energy is transmitted out along a cone-shaped surface. When

Earth intersects this cone, the radio emissions from Jupiter can exceed

the solar radio output.

Orbit and rotation

Jupiter (red) completes one orbit of the Sun (center) for every 11.86 orbits of Earth (blue)

Jupiter is the only planet whose barycenter with the Sun lies outside the volume of the Sun, though by only 7% of the Sun's radius.

The average distance between Jupiter and the Sun is 778 million km

(about 5.2 times the average distance between Earth and the Sun, or 5.2 AU) and it completes an orbit every 11.86 years. This is approximately two-fifths the orbital period of Saturn, forming a near orbital resonance between the two largest planets in the Solar System. The elliptical orbit of Jupiter is inclined 1.31° compared to Earth. Because the eccentricity of its orbit is 0.048, Jupiter's distance from the Sun varies by 75 million km between its nearest approach (perihelion) and furthest distance (aphelion).

The axial tilt

of Jupiter is relatively small: only 3.13°. As a result, it does not

experience significant seasonal changes, in contrast to, for example,

Earth and Mars.

Jupiter's rotation is the fastest of all the Solar System's planets, completing a rotation on its axis in slightly less than ten hours; this creates an equatorial bulge easily seen through an Earth-based amateur telescope. The planet is shaped as an oblate spheroid, meaning that the diameter across its equator is longer than the diameter measured between its poles. On Jupiter, the equatorial diameter is 9,275 km (5,763 mi) longer than the diameter measured through the poles.

Because Jupiter is not a solid body, its upper atmosphere undergoes differential rotation.

The rotation of Jupiter's polar atmosphere is about 5 minutes longer

than that of the equatorial atmosphere; three systems are used as frames

of reference, particularly when graphing the motion of atmospheric

features. System I applies from the latitudes 10° N to 10° S; its period

is the planet's shortest, at 9h 50m 30.0s. System II applies at all

latitudes north and south of these; its period is 9h 55m 40.6s. System

III was first defined by radio astronomers, and corresponds to the rotation of the planet's magnetosphere; its period is Jupiter's official rotation.

Observation

Jupiter is usually the fourth brightest object in the sky (after the Sun, the Moon and Venus); at times Mars appears brighter than Jupiter. Depending on Jupiter's position with respect to the Earth, it can vary in visual magnitude from as bright as −2.94 at opposition down to −1.66 during conjunction with the Sun. The mean apparent magnitude is -2.20 with a standard deviation of 0.33. The angular diameter of Jupiter likewise varies from 50.1 to 29.8 arc seconds. Favorable oppositions occur when Jupiter is passing through perihelion, an event that occurs once per orbit.

Earth overtakes Jupiter every 398.9 days as it orbits the Sun, a duration called the synodic period. As it does so, Jupiter appears to undergo retrograde motion

with respect to the background stars. That is, for a period Jupiter

seems to move backward in the night sky, performing a looping motion.

Because the orbit of Jupiter is outside that of Earth, the phase angle

of Jupiter as viewed from Earth never exceeds 11.5°. That is, the

planet always appears nearly fully illuminated when viewed through

Earth-based telescopes. It was only during spacecraft missions to

Jupiter that crescent views of the planet were obtained. A small telescope will usually show Jupiter's four Galilean moons and the prominent cloud belts across Jupiter's atmosphere. A large telescope will show Jupiter's Great Red Spot when it faces Earth.

Mythology

Jupiter, woodcut from a 1550 edition of Guido Bonatti's Liber Astronomiae

The planet Jupiter has been known since ancient times. It is visible

to the naked eye in the night sky and can occasionally be seen in the

daytime when the Sun is low. To the Babylonians, this object represented their god Marduk. They used Jupiter's roughly 12-year orbit along the ecliptic to define the constellations of their zodiac.

The Romans called it "the star of Jupiter" (Iuppiter Stella), as they believed it to be sacred to the principal god of Roman mythology, whose name comes from the Proto-Indo-European vocative compound *Dyēu-pəter (nominative: *Dyēus-pətēr, meaning "Father Sky-God", or "Father Day-God"). In turn, Jupiter was the counterpart to the mythical Greek Zeus (Ζεύς), also referred to as Dias (Δίας), the planetary name of which is retained in modern Greek. The ancient Greeks knew the planet as Phaethon, meaning "shining one".

The astronomical symbol for the planet,  , is a stylized representation of the god's lightning bolt. The original Greek deity Zeus supplies the root zeno-, used to form some Jupiter-related words, such as zenographic.

, is a stylized representation of the god's lightning bolt. The original Greek deity Zeus supplies the root zeno-, used to form some Jupiter-related words, such as zenographic.

Jovian is the adjectival form of Jupiter. The older adjectival form jovial, employed by astrologers in the Middle Ages, has come to mean "happy" or "merry", moods ascribed to Jupiter's astrological influence.

The Chinese, Vietnamese, Koreans and Japanese called it the "wood star" (Chinese: 木星; pinyin: mùxīng), based on the Chinese Five Elements. Chinese Taoism personified it as the Fu star. The Greeks called it Φαέθων (Phaethon, meaning "blazing").

In Vedic astrology, Hindu astrologers named the planet after Brihaspati, the religious teacher of the gods, and often called it "Guru", which literally means the "Heavy One".

In Germanic mythology, Jupiter is equated to Thor, whence the English name Thursday for the Roman dies Jovis.

In the Central Asian-Turkic myths, Jupiter is called Erendiz or Erentüz, from eren (of uncertain meaning) and yultuz ("star"). There are many theories about the meaning of eren.

These peoples calculated the period of the orbit of Jupiter as 11 years

and 300 days. They believed that some social and natural events

connected to Erentüz's movements on the sky.

History of research and exploration

Pre-telescopic research

Model in the Almagest of the longitudinal motion of Jupiter (☉) relative to Earth (⊕)

The observation of Jupiter dates back to at least the Babylonian astronomers of the 7th or 8th century BC. The ancient Chinese also observed the orbit of Suìxīng (歲星) and established their cycle of 12 earthly branches based on its approximate number of years; the Chinese language still uses its name (simplified as 岁) when referring to years of age. By the 4th century BC, these observations had developed into the Chinese zodiac, with each year associated with a Tai Sui star and god controlling the region of the heavens opposite Jupiter's position in the night sky; these beliefs survive in some Taoist religious practices and in the East Asian zodiac's twelve animals, now often popularly assumed to be related to the arrival of the animals before Buddha. The Chinese historian Xi Zezong has claimed that Gan De, an ancient Chinese astronomer, discovered one of Jupiter's moons in 362 BC with the unaided eye. If accurate, this would predate Galileo's discovery by nearly two millennia. In his 2nd century work the Almagest, the Hellenistic astronomer Claudius Ptolemaeus constructed a geocentric planetary model based on deferents and epicycles to explain Jupiter's motion relative to Earth, giving its orbital period around Earth as 4332.38 days, or 11.86 years.

Ground-based telescope research

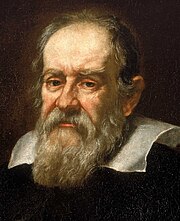

Galileo Galilei, discoverer of the four moons of Jupiter, now known as Galilean moons

In 1610, Italian polymath Galileo Galilei discovered the four largest moons of Jupiter (now known as the Galilean moons) using a telescope; thought to be the first telescopic observation of moons other than Earth's. One day after Galileo, Simon Marius independently discovered moons around Jupiter, though he did not publish his discovery in a book until 1614. It was Marius's names for the four major moons, however, that stuck—Io, Europa, Ganymede and Callisto. These findings were also the first discovery of celestial motion not apparently centered on Earth. The discovery was a major point in favor of Copernicus' heliocentric theory of the motions of the planets; Galileo's outspoken support of the Copernican theory placed him under the threat of the Inquisition.

During the 1660s, Giovanni Cassini

used a new telescope to discover spots and colorful bands on Jupiter

and observed that the planet appeared oblate; that is, flattened at the

poles. He was also able to estimate the rotation period of the planet. In 1690 Cassini noticed that the atmosphere undergoes differential rotation.

The Great Red Spot, a prominent oval-shaped feature in the

southern hemisphere of Jupiter, may have been observed as early as 1664

by Robert Hooke and in 1665 by Cassini, although this is disputed. The pharmacist Heinrich Schwabe produced the earliest known drawing to show details of the Great Red Spot in 1831.

The Red Spot was reportedly lost from sight on several occasions

between 1665 and 1708 before becoming quite conspicuous in 1878. It was

recorded as fading again in 1883 and at the start of the 20th century.

Both Giovanni Borelli

and Cassini made careful tables of the motions of Jupiter's moons,

allowing predictions of the times when the moons would pass before or

behind the planet. By the 1670s, it was observed that when Jupiter was

on the opposite side of the Sun from Earth, these events would occur

about 17 minutes later than expected. Ole Rømer deduced that light does not travel instantaneously (a conclusion that Cassini had earlier rejected), and this timing discrepancy was used to estimate the speed of light.

In 1892, E. E. Barnard observed a fifth satellite of Jupiter with the 36-inch (910 mm) refractor at Lick Observatory

in California. The discovery of this relatively small object, a

testament to his keen eyesight, quickly made him famous. This moon was

later named Amalthea. It was the last planetary moon to be discovered directly by visual observation.

Infrared image of Jupiter taken by ESO's Very Large Telescope

In 1932, Rupert Wildt identified absorption bands of ammonia and methane in the spectra of Jupiter.

Three long-lived anticyclonic features termed white ovals were

observed in 1938. For several decades they remained as separate features

in the atmosphere, sometimes approaching each other but never merging.

Finally, two of the ovals merged in 1998, then absorbed the third in

2000, becoming Oval BA.

Radiotelescope research

In 1955, Bernard Burke and Kenneth Franklin detected bursts of radio signals coming from Jupiter at 22.2 MHz.

The period of these bursts matched the rotation of the planet, and they

were also able to use this information to refine the rotation rate.

Radio bursts from Jupiter were found to come in two forms: long bursts

(or L-bursts) lasting up to several seconds, and short bursts (or

S-bursts) that had a duration of less than a hundredth of a second.

Scientists discovered that there were three forms of radio signals transmitted from Jupiter.

- Decametric radio bursts (with a wavelength of tens of meters) vary with the rotation of Jupiter, and are influenced by interaction of Io with Jupiter's magnetic field.

- Decimetric radio emission (with wavelengths measured in centimeters) was first observed by Frank Drake and Hein Hvatum in 1959. The origin of this signal was from a torus-shaped belt around Jupiter's equator. This signal is caused by cyclotron radiation from electrons that are accelerated in Jupiter's magnetic field.

- Thermal radiation is produced by heat in the atmosphere of Jupiter.

Exploration

Since 1973 a number of automated spacecraft have visited Jupiter, most notably the Pioneer 10

space probe, the first spacecraft to get close enough to Jupiter to

send back revelations about the properties and phenomena of the Solar

System's largest planet.

Flights to other planets within the Solar System are accomplished at a

cost in energy, which is described by the net change in velocity of the

spacecraft, or delta-v. Entering a Hohmann transfer orbit from Earth to Jupiter from low Earth orbit requires a delta-v of 6.3 km/s which is comparable to the 9.7 km/s delta-v needed to reach low Earth orbit. Gravity assists through planetary flybys can be used to reduce the energy required to reach Jupiter, albeit at the cost of a significantly longer flight duration.

Flyby missions

Perijove 6 pass of Jupiter as viewed by JunoCam

| Spacecraft | Closest approach |

Distance |

|---|---|---|

| Pioneer 10 | December 3, 1973 | 130,000 km |

| Pioneer 11 | December 4, 1974 | 34,000 km |

| Voyager 1 | March 5, 1979 | 349,000 km |

| Voyager 2 | July 9, 1979 | 570,000 km |

| Ulysses | February 8, 1992 | 408,894 km |

| February 4, 2004 | 120,000,000 km | |

| Cassini | December 30, 2000 | 10,000,000 km |

| New Horizons | February 28, 2007 | 2,304,535 km |

Beginning in 1973, several spacecraft have performed planetary flyby

maneuvers that brought them within observation range of Jupiter. The Pioneer

missions obtained the first close-up images of Jupiter's atmosphere and

several of its moons. They discovered that the radiation fields near

the planet were much stronger than expected, but both spacecraft managed

to survive in that environment. The trajectories of these spacecraft

were used to refine the mass estimates of the Jovian system. Radio occultations by the planet resulted in better measurements of Jupiter's diameter and the amount of polar flattening.

Six years later, the Voyager missions vastly improved the understanding of the Galilean moons

and discovered Jupiter's rings. They also confirmed that the Great Red

Spot was anticyclonic. Comparison of images showed that the Red Spot had

changed hue since the Pioneer missions, turning from orange to dark

brown. A torus of ionized atoms was discovered along Io's orbital path,

and volcanoes were found on the moon's surface, some in the process of

erupting. As the spacecraft passed behind the planet, it observed

flashes of lightning in the night side atmosphere.

The next mission to encounter Jupiter was the Ulysses solar probe. It performed a flyby maneuver to attain a polar orbit around the Sun. During this pass, the spacecraft conducted studies on Jupiter's magnetosphere. Ulysses has no cameras so no images were taken. A second flyby six years later was at a much greater distance.

Cassini views Jupiter and Io on January 1, 2001

In 2000, the Cassini probe flew by Jupiter on its way to Saturn, and provided some of the highest-resolution images ever made of the planet.

The New Horizons probe flew by Jupiter for a gravity assist en route to Pluto. Its closest approach was on February 28, 2007.

The probe's cameras measured plasma output from volcanoes on Io and

studied all four Galilean moons in detail, as well as making

long-distance observations of the outer moons Himalia and Elara. Imaging of the Jovian system began September 4, 2006.

Galileo mission

Jupiter as seen by the space probe Cassini

The first spacecraft to orbit Jupiter was the Galileo probe, which entered orbit on December 7, 1995. It orbited the planet for over seven years, conducting multiple flybys of all the Galilean moons and Amalthea. The spacecraft also witnessed the impact of Comet Shoemaker–Levy 9

as it approached Jupiter in 1994, giving a unique vantage point for the

event. Its originally designed capacity was limited by the failed

deployment of its high-gain radio antenna, although extensive

information was still gained about the Jovian system from Galileo.

A 340-kilogram titanium atmospheric probe was released from the spacecraft in July 1995, entering Jupiter's atmosphere on December 7. It parachuted through 150 km (93 mi) of the atmosphere at a speed of about 2,575 km/h (1600 mph) and collected data for 57.6 minutes before the signal was lost at a pressure of about 23 atmospheres at a temperature of 153 °C. It melted thereafter, and possibly vaporized. The Galileo

orbiter itself experienced a more rapid version of the same fate when

it was deliberately steered into the planet on September 21, 2003 at a

speed of over 50 km/s to avoid any possibility of it crashing into and

possibly contaminating Europa, a moon which has been hypothesized to

have the possibility of harboring life.

Data from this mission revealed that hydrogen composes up to 90% of Jupiter's atmosphere.

The recorded temperature was more than 300 °C (>570 °F) and the

windspeed measured more than 644 km/h (>400 mph) before the probes

vaporised.

Juno mission

NASA's Juno mission arrived at Jupiter on July 4, 2016, and is expected to complete 37 orbits over the next 20 months. The mission plan called for Juno to study the planet in detail from a polar orbit.

On August 27, 2016, the spacecraft completed its first fly-by of

Jupiter and sent back the first-ever images of Jupiter’s north pole.

Future probes

The next planned mission to the Jovian system will be the European Space Agency's Jupiter Icy Moon Explorer (JUICE), due to launch in 2022, followed by NASA's Europa Clipper mission in 2025.

Canceled missions

There has been great interest in studying the icy moons in detail

because of the possibility of subsurface liquid oceans on Jupiter's

moons Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto. Funding difficulties have delayed

progress. NASA's JIMO (Jupiter Icy Moons Orbiter) was cancelled in 2005. A subsequent proposal was developed for a joint NASA/ESA mission called EJSM/Laplace, with a provisional launch date around 2020. EJSM/Laplace would have consisted of the NASA-led Jupiter Europa Orbiter and the ESA-led Jupiter Ganymede Orbiter.

However, ESA had formally ended the partnership by April 2011, citing

budget issues at NASA and the consequences on the mission timetable.

Instead, ESA planned to go ahead with a European-only mission to compete

in its L1 Cosmic Vision selection.

Moons

Jupiter has 79 known natural satellites.

Of these, 63 are less than 10 kilometres in diameter and have only been

discovered since 1975. The four largest moons, visible from Earth with

binoculars on a clear night, known as the "Galilean moons", are Io, Europa, Ganymede, and Callisto.

Galilean moons

The moons discovered by Galileo—Io, Europa, Ganymede, and

Callisto—are among the largest satellites in the Solar System. The

orbits of three of them (Io, Europa, and Ganymede) form a pattern known

as a Laplace resonance;

for every four orbits that Io makes around Jupiter, Europa makes

exactly two orbits and Ganymede makes exactly one. This resonance causes

the gravitational

effects of the three large moons to distort their orbits into

elliptical shapes, because each moon receives an extra tug from its

neighbors at the same point in every orbit it makes. The tidal force from Jupiter, on the other hand, works to circularize their orbits.

The eccentricity

of their orbits causes regular flexing of the three moons' shapes, with

Jupiter's gravity stretching them out as they approach it and allowing

them to spring back to more spherical shapes as they swing away. This

tidal flexing heats the moons' interiors by friction. This is seen most dramatically in the extraordinary volcanic activity of innermost Io (which is subject to the strongest tidal forces), and to a lesser degree in the geological youth of Europa's surface (indicating recent resurfacing of the moon's exterior).

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| The Galilean moons Io, Europa, Ganymede, Callisto (in order of increasing distance from Jupiter) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Classification

Before the discoveries of the Voyager missions, Jupiter's moons were

arranged neatly into four groups of four, based on commonality of their orbital elements.

Since then, the large number of new small outer moons has complicated

this picture. There are now thought to be six main groups, although some

are more distinct than others.

A basic sub-division is a grouping of the eight inner regular

moons, which have nearly circular orbits near the plane of Jupiter's

equator and are thought to have formed with Jupiter. The remainder of

the moons consist of an unknown number of small irregular moons with

elliptical and inclined orbits, which are thought to be captured

asteroids or fragments of captured asteroids. Irregular moons that

belong to a group share similar orbital elements and thus may have a

common origin, perhaps as a larger moon or captured body that broke up.

| Regular moons | |

|---|---|

| Inner group | The inner group of four small moons all have diameters of less than 200 km, orbit at radii less than 200,000 km, and have orbital inclinations of less than half a degree. |

| Galilean moons | These four moons, discovered by Galileo Galilei and by Simon Marius in parallel, orbit between 400,000 and 2,000,000 km, and are some of the largest moons in the Solar System. |

| Irregular moons | |

| Themisto | This is a single moon belonging to a group of its own, orbiting halfway between the Galilean moons and the Himalia group. |

| Himalia group | A tightly clustered group of moons with orbits around 11,000,000–12,000,000 km from Jupiter. |

| Carpo | Another isolated case; at the inner edge of the Ananke group, it orbits Jupiter in prograde direction. |

| Valetudo | A third isolated case, which has a prograde orbit but overlaps the retrograde groups listed below; this may result in a future collision. |

| Ananke group | This retrograde orbit group has rather indistinct borders, averaging 21,276,000 km from Jupiter with an average inclination of 149 degrees. |

| Carme group | A fairly distinct retrograde group that averages 23,404,000 km from Jupiter with an average inclination of 165 degrees. |

| Pasiphae group | A dispersed and only vaguely distinct retrograde group that covers all the outermost moons. |

Planetary rings

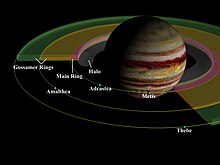

The rings of Jupiter

Jupiter has a faint planetary ring system composed of three main segments: an inner torus of particles known as the halo, a relatively bright main ring, and an outer gossamer ring. These rings appear to be made of dust, rather than ice as with Saturn's rings. The main ring is probably made of material ejected from the satellites Adrastea and Metis.

Material that would normally fall back to the moon is pulled into

Jupiter because of its strong gravitational influence. The orbit of the

material veers towards Jupiter and new material is added by additional

impacts. In a similar way, the moons Thebe and Amalthea probably produce the two distinct components of the dusty gossamer ring. There is also evidence of a rocky ring strung along Amalthea's orbit which may consist of collisional debris from that moon.

Interaction with the Solar System

Along with the Sun, the gravitational influence of Jupiter has helped shape the Solar System. The orbits of most of the system's planets lie closer to Jupiter's orbital plane than the Sun's equatorial plane (Mercury is the only planet that is closer to the Sun's equator in orbital tilt), the Kirkwood gaps in the asteroid belt are mostly caused by Jupiter, and the planet may have been responsible for the Late Heavy Bombardment of the inner Solar System's history.

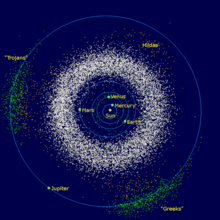

This diagram shows the Trojan asteroids in Jupiter's orbit, as well as the main asteroid belt.

Along with its moons, Jupiter's gravitational field controls numerous asteroids that have settled into the regions of the Lagrangian points preceding and following Jupiter in its orbit around the Sun. These are known as the Trojan asteroids, and are divided into Greek and Trojan "camps" to commemorate the Iliad. The first of these, 588 Achilles, was discovered by Max Wolf in 1906; since then more than two thousand have been discovered. The largest is 624 Hektor.

Most short-period comets belong to the Jupiter family—defined as comets with semi-major axes smaller than Jupiter's. Jupiter family comets are thought to form in the Kuiper belt outside the orbit of Neptune. During close encounters with Jupiter their orbits are perturbed into a smaller period and then circularized by regular gravitational interaction with the Sun and Jupiter.

Due to the magnitude of Jupiter's mass, the center of gravity between it and the Sun lies just above the Sun's surface. Jupiter is the only body in the Solar System for which this is true.

Impacts

Hubble image taken on July 23, 2009, showing a blemish of about 8,000 km (5,000 mi) long left by the 2009 Jupiter impact.

Jupiter has been called the Solar System's vacuum cleaner, because of its immense gravity well and location near the inner Solar System. It receives the most frequent comet impacts of the Solar System's planets. It was thought that the planet served to partially shield the inner system from cometary bombardment.

However, recent computer simulations suggest that Jupiter does not

cause a net decrease in the number of comets that pass through the inner

Solar System, as its gravity perturbs their orbits inward roughly as

often as it accretes or ejects them. This topic remains controversial among scientists, as some think it draws comets towards Earth from the Kuiper belt while others think that Jupiter protects Earth from the alleged Oort cloud. Jupiter experiences about 200 times more asteroid and comet impacts than Earth.

A 1997 survey of early astronomical records and drawings suggested that a certain dark surface feature discovered by astronomer Giovanni Cassini

in 1690 may have been an impact scar. The survey initially produced

eight more candidate sites as potential impact observations that he and

others had recorded between 1664 and 1839. It was later determined,

however, that these candidate sites had little or no possibility of

being the results of the proposed impacts.

More recent discoveries include the following:

- A fireball was photographed by Voyager 1 during its Jupiter encounter in March 1979.

- During the period July 16, 1994, to July 22, 1994, over 20 fragments from the comet Shoemaker–Levy 9 (SL9, formally designated D/1993 F2) collided with Jupiter's southern hemisphere, providing the first direct observation of a collision between two Solar System objects. This impact provided useful data on the composition of Jupiter's atmosphere.

- On July 19, 2009, an impact site was discovered at approximately 216 degrees longitude in System 2. This impact left behind a black spot in Jupiter's atmosphere, similar in size to Oval BA. Infrared observation showed a bright spot where the impact took place, meaning the impact warmed up the lower atmosphere in the area near Jupiter's south pole.

- A fireball, smaller than the previous observed impacts, was detected on June 3, 2010, by Anthony Wesley, an amateur astronomer in Australia, and was later discovered to have been captured on video by another amateur astronomer in the Philippines.

- Yet another fireball was seen on August 20, 2010.

- On September 10, 2012, another fireball was detected.

- On March 17, 2016 an asteroid or comet struck and was filmed on video.