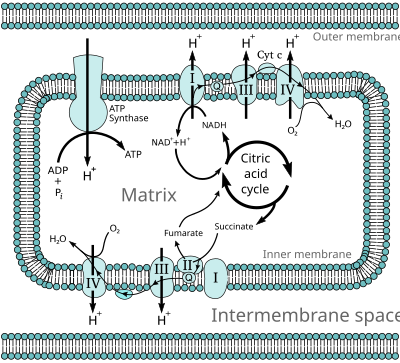

The electron transport chain in the cell is the site of oxidative phosphorylation in prokaryotes. The NADH and succinate generated in the citric acid cycle are oxidized, releasing energy to power the ATP synthase.

Oxidative phosphorylation (UK /ɒkˈsɪd.ə.tɪv/, US /ˈɑːk.sɪˌdeɪ.tɪv/) is the metabolic pathway in which cells use enzymes to oxidize nutrients, thereby releasing energy which is used to produce adenosine triphosphate (ATP). In most eukaryotes, this takes place inside mitochondria. Almost all aerobic organisms

carry out oxidative phosphorylation. This pathway is probably so

pervasive because it is a highly efficient way of releasing energy,

compared to alternative fermentation processes such as anaerobic glycolysis.

During oxidative phosphorylation, electrons are transferred from electron donors to electron acceptors such as oxygen, in redox reactions. These redox reactions release energy, which is used to form ATP. In eukaryotes, these redox reactions are carried out by a series of protein complexes within the inner membrane of the cell's mitochondria, whereas, in prokaryotes, these proteins are located in the cells' intermembrane space. These linked sets of proteins are called electron transport chains.

In eukaryotes, five main protein complexes are involved, whereas in

prokaryotes many different enzymes are present, using a variety of

electron donors and acceptors.

The energy released by electrons flowing through this electron transport chain is used to transport protons across the inner mitochondrial membrane, in a process called electron transport. This generates potential energy in the form of a pH gradient and an electrical potential

across this membrane. This store of energy is tapped when protons flow

back across the membrane and down the potential energy gradient, through

a large enzyme called ATP synthase; this process is known as chemiosmosis. The ATP synthase uses the energy to transform adenosine diphosphate (ADP) into adenosine triphosphate, in a phosphorylation reaction. The reaction is driven by the proton flow, which forces the rotation of a part of the enzyme; the ATP synthase is a rotary mechanical motor.

Although oxidative phosphorylation is a vital part of metabolism, it produces reactive oxygen species such as superoxide and hydrogen peroxide, which lead to propagation of free radicals, damaging cells and contributing to disease and, possibly, aging (senescence). The enzymes carrying out this metabolic pathway are also the target of many drugs and poisons that inhibit their activities.

It is the terminal process of cellular respiration in eukaryotes and accounts for high ATP yield.

Chemiosmosis

Oxidative phosphorylation works by using energy-releasing chemical reactions to drive energy-requiring reactions: The two sets of reactions are said to be coupled.

This means one cannot occur without the other. The flow of electrons

through the electron transport chain, from electron donors such as NADH to electron acceptors such as oxygen, is an exergonic process – it releases energy, whereas the synthesis of ATP is an endergonic

process, which requires an input of energy. Both the electron transport

chain and the ATP synthase are embedded in a membrane, and energy is

transferred from electron transport chain to the ATP synthase by

movements of protons across this membrane, in a process called chemiosmosis. In practice, this is like a simple electric circuit,

with a current of protons being driven from the negative N-side of the

membrane to the positive P-side by the proton-pumping enzymes of the

electron transport chain. These enzymes are like a battery, as they perform work to drive current through the circuit. The movement of protons creates an electrochemical gradient across the membrane, which is often called the proton-motive force. It has two components: a difference in proton concentration (a H+ gradient, ΔpH) and a difference in electric potential, with the N-side having a negative charge.

ATP synthase releases this stored energy by completing the

circuit and allowing protons to flow down the electrochemical gradient,

back to the N-side of the membrane.

The electrochemical gradient drives the rotation of part of the

enzyme's structure and couples this motion to the synthesis of ATP.

The two components of the proton-motive force are thermodynamically equivalent: In mitochondria, the largest part of energy is provided by the potential; in alkaliphile bacteria the electrical energy even has to compensate for a counteracting inverse pH difference. Inversely, chloroplasts

operate mainly on ΔpH. However, they also require a small membrane

potential for the kinetics of ATP synthesis. In the case of the fusobacterium Propionigenium modestum it drives the counter-rotation of subunits a and c of the FO motor of ATP synthase.

The amount of energy released by oxidative phosphorylation is high, compared with the amount produced by anaerobic fermentation. Glycolysis

produces only 2 ATP molecules, but somewhere between 30 and 36 ATPs are

produced by the oxidative phosphorylation of the 10 NADH and 2

succinate molecules made by converting one molecule of glucose to carbon dioxide and water, while each cycle of beta oxidation of a fatty acid

yields about 14 ATPs. These ATP yields are theoretical maximum values;

in practice, some protons leak across the membrane, lowering the yield

of ATP.

Electron and proton transfer molecules

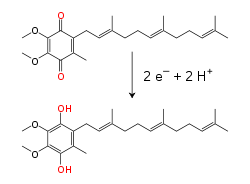

Reduction of coenzyme Q from its ubiquinone form (Q) to the reduced ubiquinol form (QH2).

The electron transport chain carries both protons and electrons,

passing electrons from donors to acceptors, and transporting protons

across a membrane. These processes use both soluble and protein-bound

transfer molecules. In mitochondria, electrons are transferred within

the intermembrane space by the water-soluble electron transfer protein cytochrome c. This carries only electrons, and these are transferred by the reduction and oxidation of an iron atom that the protein holds within a heme group in its structure. Cytochrome c is also found in some bacteria, where it is located within the periplasmic space.

Within the inner mitochondrial membrane, the lipid-soluble electron carrier coenzyme Q10 (Q) carries both electrons and protons by a redox cycle. This small benzoquinone molecule is very hydrophobic, so it diffuses freely within the membrane. When Q accepts two electrons and two protons, it becomes reduced to the ubiquinol form (QH2); when QH2 releases two electrons and two protons, it becomes oxidized back to the ubiquinone (Q) form. As a result, if two enzymes are arranged so that Q is reduced on one side of the membrane and QH2 oxidized on the other, ubiquinone will couple these reactions and shuttle protons across the membrane. Some bacterial electron transport chains use different quinones, such as menaquinone, in addition to ubiquinone.

Within proteins, electrons are transferred between flavin cofactors,

iron–sulfur clusters, and cytochromes. There are several types of

iron–sulfur cluster. The simplest kind found in the electron transfer

chain consists of two iron atoms joined by two atoms of inorganic sulfur;

these are called [2Fe–2S] clusters. The second kind, called [4Fe–4S],

contains a cube of four iron atoms and four sulfur atoms. Each iron atom

in these clusters is coordinated by an additional amino acid, usually by the sulfur atom of cysteine.

Metal ion cofactors undergo redox reactions without binding or

releasing protons, so in the electron transport chain they serve solely

to transport electrons through proteins. Electrons move quite long

distances through proteins by hopping along chains of these cofactors. This occurs by quantum tunnelling, which is rapid over distances of less than 1.4×10−9 m.

Eukaryotic electron transport chains

Many catabolic biochemical processes, such as glycolysis, the citric acid cycle, and beta oxidation, produce the reduced coenzyme NADH. This coenzyme contains electrons that have a high transfer potential;

in other words, they will release a large amount of energy upon

oxidation. However, the cell does not release this energy all at once,

as this would be an uncontrollable reaction. Instead, the electrons are

removed from NADH and passed to oxygen through a series of enzymes that

each release a small amount of the energy. This set of enzymes,

consisting of complexes I through IV, is called the electron transport

chain and is found in the inner membrane of the mitochondrion. Succinate is also oxidized by the electron transport chain, but feeds into the pathway at a different point.

In eukaryotes, the enzymes in this electron transport system use the energy released from the oxidation of NADH to pump protons across the inner membrane of the mitochondrion. This causes protons to build up in the intermembrane space, and generates an electrochemical gradient

across the membrane. The energy stored in this potential is then used

by ATP synthase to produce ATP. Oxidative phosphorylation in the

eukaryotic mitochondrion is the best-understood example of this process.

The mitochondrion is present in almost all eukaryotes, with the

exception of anaerobic protozoa such as Trichomonas vaginalis that instead reduce protons to hydrogen in a remnant mitochondrion called a hydrogenosome.

| Respiratory enzyme | Redox pair | Midpoint potential

(Volts)

|

|---|---|---|

| NADH dehydrogenase | NAD+ / NADH | −0.32 |

| Succinate dehydrogenase | FMN or FAD / FMNH2 or FADH2 | −0.20 |

| Cytochrome bc1 complex | Coenzyme Q10ox / Coenzyme Q10red | +0.06 |

| Cytochrome bc1 complex | Cytochrome box / Cytochrome bred | +0.12 |

| Complex IV | Cytochrome cox / Cytochrome cred | +0.22 |

| Complex IV | Cytochrome aox / Cytochrome ared | +0.29 |

| Complex IV | O2 / HO− | +0.82 |

| Conditions: pH = 7 | ||

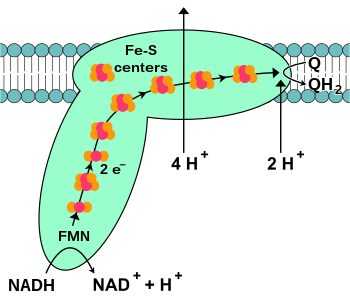

NADH-coenzyme Q oxidoreductase (complex I)

Complex I or NADH-Q oxidoreductase.

The abbreviations are discussed in the text. In all diagrams of

respiratory complexes in this article, the matrix is at the bottom, with

the intermembrane space above.

NADH-coenzyme Q oxidoreductase, also known as NADH dehydrogenase or complex I, is the first protein in the electron transport chain. Complex I is a giant enzyme with the mammalian complex I having 46 subunits and a molecular mass of about 1,000 kilodaltons (kDa). The structure is known in detail only from a bacterium; in most organisms the complex resembles a boot with a large "ball" poking out from the membrane into the mitochondrion. The genes that encode the individual proteins are contained in both the cell nucleus and the mitochondrial genome, as is the case for many enzymes present in the mitochondrion.

The reaction that is catalyzed by this enzyme is the two electron oxidation of NADH by coenzyme Q10 or ubiquinone (represented as Q in the equation below), a lipid-soluble quinone that is found in the mitochondrion membrane:

(1)

|

The start of the reaction, and indeed of the entire electron chain,

is the binding of a NADH molecule to complex I and the donation of two

electrons. The electrons enter complex I via a prosthetic group attached to the complex, flavin mononucleotide (FMN). The addition of electrons to FMN converts it to its reduced form, FMNH2. The electrons are then transferred through a series of iron–sulfur clusters: the second kind of prosthetic group present in the complex. There are both [2Fe–2S] and [4Fe–4S] iron–sulfur clusters in complex I.

As the electrons pass through this complex, four protons are

pumped from the matrix into the intermembrane space. Exactly how this

occurs is unclear, but it seems to involve conformational changes

in complex I that cause the protein to bind protons on the N-side of

the membrane and release them on the P-side of the membrane. Finally, the electrons are transferred from the chain of iron–sulfur clusters to a ubiquinone molecule in the membrane.

Reduction of ubiquinone also contributes to the generation of a proton

gradient, as two protons are taken up from the matrix as it is reduced

to ubiquinol (QH2).

Succinate-Q oxidoreductase (complex II)

Complex II: Succinate-Q oxidoreductase.

Succinate-Q oxidoreductase, also known as complex II or succinate dehydrogenase, is a second entry point to the electron transport chain.

It is unusual because it is the only enzyme that is part of both the

citric acid cycle and the electron transport chain. Complex II consists

of four protein subunits and contains a bound flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD) cofactor, iron–sulfur clusters, and a heme

group that does not participate in electron transfer to coenzyme Q, but

is believed to be important in decreasing production of reactive oxygen

species. It oxidizes succinate to fumarate

and reduces ubiquinone. As this reaction releases less energy than the

oxidation of NADH, complex II does not transport protons across the

membrane and does not contribute to the proton gradient.

(2)

|

In some eukaryotes, such as the parasitic worm Ascaris suum,

an enzyme similar to complex II, fumarate reductase

(menaquinol:fumarate

oxidoreductase, or QFR), operates in reverse to oxidize ubiquinol and

reduce fumarate. This allows the worm to survive in the anaerobic

environment of the large intestine, carrying out anaerobic oxidative phosphorylation with fumarate as the electron acceptor. Another unconventional function of complex II is seen in the malaria parasite Plasmodium falciparum.

Here, the reversed action of complex II as an oxidase is important in

regenerating ubiquinol, which the parasite uses in an unusual form of pyrimidine biosynthesis.

Electron transfer flavoprotein-Q oxidoreductase

Electron transfer flavoprotein-ubiquinone oxidoreductase (ETF-Q oxidoreductase), also known as electron transferring-flavoprotein dehydrogenase, is a third entry point to the electron transport chain. It is an enzyme that accepts electrons from electron-transferring flavoprotein in the mitochondrial matrix, and uses these electrons to reduce ubiquinone. This enzyme contains a flavin

and a [4Fe–4S] cluster, but, unlike the other respiratory complexes, it

attaches to the surface of the membrane and does not cross the lipid

bilayer.

(3)

|

In mammals, this metabolic pathway is important in beta oxidation of fatty acids and catabolism of amino acids and choline, as it accepts electrons from multiple acetyl-CoA dehydrogenases.

In plants, ETF-Q oxidoreductase is also important in the metabolic

responses that allow survival in extended periods of darkness.

Q-cytochrome c oxidoreductase (complex III)

The two electron transfer steps in complex III: Q-cytochrome c oxidoreductase. After each step, Q (in the upper part of the figure) leaves the enzyme.

Q-cytochrome c oxidoreductase is also known as cytochrome c reductase, cytochrome bc1 complex, or simply complex III. In mammals, this enzyme is a dimer, with each subunit complex containing 11 protein subunits, an [2Fe-2S] iron–sulfur cluster and three cytochromes: one cytochrome c1 and two b cytochromes. A cytochrome is a kind of electron-transferring protein that contains at least one heme

group. The iron atoms inside complex III’s heme groups alternate

between a reduced ferrous (+2) and oxidized ferric (+3) state as the

electrons are transferred through the protein.

The reaction catalyzed by complex III is the oxidation of one molecule of ubiquinol and the reduction of two molecules of cytochrome c,

a heme protein loosely associated with the mitochondrion. Unlike

coenzyme Q, which carries two electrons, cytochrome c carries only one

electron.

(4)

|

As only one of the electrons can be transferred from the QH2

donor to a cytochrome c acceptor at a time, the reaction mechanism of

complex III is more elaborate than those of the other respiratory

complexes, and occurs in two steps called the Q cycle. In the first step, the enzyme binds three substrates, first, QH2, which is then oxidized, with one electron being passed to the second substrate, cytochrome c. The two protons released from QH2 pass into the intermembrane space. The third substrate is Q, which accepts the second electron from the QH2 and is reduced to Q.−, which is the ubisemiquinone free radical.

The first two substrates are released, but this ubisemiquinone

intermediate remains bound. In the second step, a second molecule of QH2

is bound and again passes its first electron to a cytochrome c

acceptor. The second electron is passed to the bound ubisemiquinone,

reducing it to QH2 as it gains two protons from the mitochondrial matrix. This QH2 is then released from the enzyme.

As coenzyme Q is reduced to ubiquinol on the inner side of the

membrane and oxidized to ubiquinone on the other, a net transfer of

protons across the membrane occurs, adding to the proton gradient.

The rather complex two-step mechanism by which this occurs is

important, as it increases the efficiency of proton transfer. If,

instead of the Q cycle, one molecule of QH2 were used to

directly reduce two molecules of cytochrome c, the efficiency would be

halved, with only one proton transferred per cytochrome c reduced.

Cytochrome c oxidase (complex IV)

Complex IV: cytochrome c oxidase.

Cytochrome c oxidase, also known as complex IV, is the final protein complex in the electron transport chain.

The mammalian enzyme has an extremely complicated structure and

contains 13 subunits, two heme groups, as well as multiple metal ion

cofactors – in all, three atoms of copper, one of magnesium and one of zinc.

This enzyme mediates the final reaction in the electron transport

chain and transfers electrons to oxygen, while pumping protons across

the membrane. The final electron acceptor oxygen, which is also called the terminal electron acceptor,

is reduced to water in this step. Both the direct pumping of protons

and the consumption of matrix protons in the reduction of oxygen

contribute to the proton gradient. The reaction catalyzed is the

oxidation of cytochrome c and the reduction of oxygen:

(5)

|

Alternative reductases and oxidases

Many

eukaryotic organisms have electron transport chains that differ from

the much-studied mammalian enzymes described above. For example, plants

have alternative NADH oxidases, which oxidize NADH in the cytosol

rather than in the mitochondrial matrix, and pass these electrons to the

ubiquinone pool.

These enzymes do not transport protons, and, therefore, reduce

ubiquinone without altering the electrochemical gradient across the

inner membrane.

Another example of a divergent electron transport chain is the alternative oxidase, which is found in plants, as well as some fungi, protists, and possibly some animals. This enzyme transfers electrons directly from ubiquinol to oxygen.

The electron transport pathways produced by these alternative NADH and ubiquinone oxidases have lower ATP

yields than the full pathway. The advantages produced by a shortened

pathway are not entirely clear. However, the alternative oxidase is

produced in response to stresses such as cold, reactive oxygen species, and infection by pathogens, as well as other factors that inhibit the full electron transport chain. Alternative pathways might, therefore, enhance an organisms' resistance to injury, by reducing oxidative stress.

Organization of complexes

The

original model for how the respiratory chain complexes are organized

was that they diffuse freely and independently in the mitochondrial

membrane. However, recent data suggest that the complexes might form higher-order structures called supercomplexes or "respirasomes". In this model, the various complexes exist as organized sets of interacting enzymes.

These associations might allow channeling of substrates between the

various enzyme complexes, increasing the rate and efficiency of electron

transfer.

Within such mammalian supercomplexes, some components would be present

in higher amounts than others, with some data suggesting a ratio between

complexes I/II/III/IV and the ATP synthase of approximately 1:1:3:7:4.

However, the debate over this supercomplex hypothesis is not completely

resolved, as some data do not appear to fit with this model.

Prokaryotic electron transport chains

In contrast to the general similarity in structure and function of the electron transport chains in eukaryotes, bacteria and archaea possess a large variety of electron-transfer enzymes. These use an equally wide set of chemicals as substrates.

In common with eukaryotes, prokaryotic electron transport uses the

energy released from the oxidation of a substrate to pump ions across a

membrane and generate an electrochemical gradient. In the bacteria,

oxidative phosphorylation in Escherichia coli is understood in most detail, while archaeal systems are at present poorly understood.

The main difference between eukaryotic and prokaryotic oxidative

phosphorylation is that bacteria and archaea use many different

substances to donate or accept electrons. This allows prokaryotes to

grow under a wide variety of environmental conditions. In E. coli,

for example, oxidative phosphorylation can be driven by a large number

of pairs of reducing agents and oxidizing agents, which are listed

below. The midpoint potential

of a chemical measures how much energy is released when it is oxidized

or reduced, with reducing agents having negative potentials and

oxidizing agents positive potentials.

| Respiratory enzyme | Redox pair | Midpoint potential

(Volts)

|

|---|---|---|

| Formate dehydrogenase | Bicarbonate / Formate | −0.43 |

| Hydrogenase | Proton / Hydrogen | −0.42 |

| NADH dehydrogenase | NAD+ / NADH | −0.32 |

| Glycerol-3-phosphate dehydrogenase | DHAP / Gly-3-P | −0.19 |

| Pyruvate oxidase | Acetate + Carbon dioxide / Pyruvate | ? |

| Lactate dehydrogenase | Pyruvate / Lactate | −0.19 |

| D-amino acid dehydrogenase | 2-oxoacid + ammonia / D-amino acid | ? |

| Glucose dehydrogenase | Gluconate / Glucose | −0.14 |

| Succinate dehydrogenase | Fumarate / Succinate | +0.03 |

| Ubiquinol oxidase | Oxygen / Water | +0.82 |

| Nitrate reductase | Nitrate / Nitrite | +0.42 |

| Nitrite reductase | Nitrite / Ammonia | +0.36 |

| Dimethyl sulfoxide reductase | DMSO / DMS | +0.16 |

| Trimethylamine N-oxide reductase | TMAO / TMA | +0.13 |

| Fumarate reductase | Fumarate / Succinate | +0.03 |

As shown above, E. coli can grow with reducing agents such as

formate, hydrogen, or lactate as electron donors, and nitrate, DMSO, or

oxygen as acceptors.

The larger the difference in midpoint potential between an oxidizing

and reducing agent, the more energy is released when they react. Out of

these compounds, the succinate/fumarate pair is unusual, as its midpoint

potential is close to zero. Succinate can therefore be oxidized to

fumarate if a strong oxidizing agent such as oxygen is available, or

fumarate can be reduced to succinate using a strong reducing agent such

as formate. These alternative reactions are catalyzed by succinate dehydrogenase and fumarate reductase, respectively.

Some prokaryotes use redox pairs that have only a small difference in midpoint potential. For example, nitrifying bacteria such as Nitrobacter

oxidize nitrite to nitrate, donating the electrons to oxygen. The small

amount of energy released in this reaction is enough to pump protons

and generate ATP, but not enough to produce NADH or NADPH directly for

use in anabolism. This problem is solved by using a nitrite oxidoreductase

to produce enough proton-motive force to run part of the electron

transport chain in reverse, causing complex I to generate NADH.

Prokaryotes control their use of these electron donors and

acceptors by varying which enzymes are produced, in response to

environmental conditions.

This flexibility is possible because different oxidases and reductases

use the same ubiquinone pool. This allows many combinations of enzymes

to function together, linked by the common ubiquinol intermediate. These respiratory chains therefore have a modular design, with easily interchangeable sets of enzyme systems.

In addition to this metabolic diversity, prokaryotes also possess a range of isozymes – different enzymes that catalyze the same reaction. For example, in E. coli,

there are two different types of ubiquinol oxidase using oxygen as an

electron acceptor. Under highly aerobic conditions, the cell uses an

oxidase with a low affinity for oxygen that can transport two protons

per electron. However, if levels of oxygen fall, they switch to an

oxidase that transfers only one proton per electron, but has a high

affinity for oxygen.

ATP synthase (complex V)

ATP synthase, also called complex V, is the final enzyme in

the oxidative phosphorylation pathway. This enzyme is found in all forms

of life and functions in the same way in both prokaryotes and

eukaryotes. The enzyme uses the energy stored in a proton gradient across a membrane to drive the synthesis of ATP from ADP and phosphate (Pi). Estimates of the number of protons required to synthesize one ATP have ranged from three to four, with some suggesting cells can vary this ratio, to suit different conditions.

(6)

|

This phosphorylation reaction is an equilibrium,

which can be shifted by altering the proton-motive force. In the

absence of a proton-motive force, the ATP synthase reaction will run

from right to left, hydrolyzing ATP and pumping protons out of the

matrix across the membrane. However, when the proton-motive force is

high, the reaction is forced to run in the opposite direction; it

proceeds from left to right, allowing protons to flow down their

concentration gradient and turning ADP into ATP. Indeed, in the closely related vacuolar type H+-ATPases, the hydrolysis reaction is used to acidify cellular compartments, by pumping protons and hydrolysing ATP.

ATP synthase is a massive protein complex with a mushroom-like

shape. The mammalian enzyme complex contains 16 subunits and has a mass

of approximately 600 kilodaltons. The portion embedded within the membrane is called FO and contains a ring of c subunits and the proton channel. The stalk and the ball-shaped headpiece is called F1 and is the site of ATP synthesis. The ball-shaped complex at the end of the F1

portion contains six proteins of two different kinds (three α subunits

and three β subunits), whereas the "stalk" consists of one protein: the γ

subunit, with the tip of the stalk extending into the ball of α and β

subunits.

Both the α and β subunits bind nucleotides, but only the β subunits

catalyze the ATP synthesis reaction. Reaching along the side of the F1 portion and back into the membrane is a long rod-like subunit that anchors the α and β subunits into the base of the enzyme.

As protons cross the membrane through the channel in the base of ATP synthase, the FO proton-driven motor rotates. Rotation might be caused by changes in the ionization of amino acids in the ring of c subunits causing electrostatic interactions that propel the ring of c subunits past the proton channel. This rotating ring in turn drives the rotation of the central axle

(the γ subunit stalk) within the α and β subunits. The α and β subunits

are prevented from rotating themselves by the side-arm, which acts as a

stator.

This movement of the tip of the γ subunit within the ball of α and β

subunits provides the energy for the active sites in the β subunits to

undergo a cycle of movements that produces and then releases ATP.

Mechanism of ATP synthase. ATP is shown in red, ADP and phosphate in pink and the rotating γ subunit in black.

This ATP synthesis reaction is called the binding change mechanism and involves the active site of a β subunit cycling between three states.

In the "open" state, ADP and phosphate enter the active site (shown in

brown in the diagram). The protein then closes up around the molecules

and binds them loosely – the "loose" state (shown in red). The enzyme

then changes shape again and forces these molecules together, with the

active site in the resulting "tight" state (shown in pink) binding the

newly produced ATP molecule with very high affinity.

Finally, the active site cycles back to the open state, releasing ATP

and binding more ADP and phosphate, ready for the next cycle.

In some bacteria and archaea, ATP synthesis is driven by the

movement of sodium ions through the cell membrane, rather than the

movement of protons. Archaea such as Methanococcus also contain the A1Ao

synthase, a form of the enzyme that contains additional proteins with

little similarity in sequence to other bacterial and eukaryotic ATP

synthase subunits. It is possible that, in some species, the A1Ao form of the enzyme is a specialized sodium-driven ATP synthase, but this might not be true in all cases.

Reactive oxygen species

Molecular oxygen is an ideal terminal electron acceptor because it is a strong oxidizing agent. The reduction of oxygen does involve potentially harmful intermediates.

Although the transfer of four electrons and four protons reduces oxygen

to water, which is harmless, transfer of one or two electrons produces superoxide or peroxide anions, which are dangerously reactive.

(7)

|

These reactive oxygen species and their reaction products, such as the hydroxyl radical, are very harmful to cells, as they oxidize proteins and cause mutations in DNA. This cellular damage might contribute to disease and is proposed as one cause of aging.

The cytochrome c oxidase complex is highly efficient at reducing

oxygen to water, and it releases very few partly reduced intermediates;

however small amounts of superoxide anion and peroxide are produced by

the electron transport chain. Particularly important is the reduction of coenzyme Q

in complex III, as a highly reactive ubisemiquinone free radical is

formed as an intermediate in the Q cycle. This unstable species can lead

to electron "leakage" when electrons transfer directly to oxygen,

forming superoxide.

As the production of reactive oxygen species by these proton-pumping

complexes is greatest at high membrane potentials, it has been proposed

that mitochondria regulate their activity to maintain the membrane

potential within a narrow range that balances ATP production against

oxidant generation. For instance, oxidants can activate uncoupling proteins that reduce membrane potential.

To counteract these reactive oxygen species, cells contain numerous antioxidant systems, including antioxidant vitamins such as vitamin C and vitamin E, and antioxidant enzymes such as superoxide dismutase, catalase, and peroxidases, which detoxify the reactive species, limiting damage to the cell.

Inhibitors

There are several well-known drugs and toxins

that inhibit oxidative phosphorylation. Although any one of these

toxins inhibits only one enzyme in the electron transport chain,

inhibition of any step in this process will halt the rest of the

process. For example, if oligomycin inhibits ATP synthase, protons cannot pass back into the mitochondrion.

As a result, the proton pumps are unable to operate, as the gradient

becomes too strong for them to overcome. NADH is then no longer oxidized

and the citric acid cycle ceases to operate because the concentration

of NAD+ falls below the concentration that these enzymes can use.

| Compounds | Use | Site of action | Effect on oxidative phosphorylation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cyanide Carbon monoxide Azide Hydrogen sulfide |

Poisons | Complex IV | Inhibit the electron transport chain by binding more strongly than oxygen to the Fe–Cu center in cytochrome c oxidase, preventing the reduction of oxygen. |

| Oligomycin | Antibiotic | Complex V | Inhibits ATP synthase by blocking the flow of protons through the Fo subunit. |

| CCCP 2,4-Dinitrophenol |

Poisons, weight-loss | Inner membrane | Ionophores that disrupt the proton gradient by carrying protons across a membrane. This ionophore uncouples proton pumping from ATP synthesis because it carries protons across the inner mitochondrial membrane. |

| Rotenone | Pesticide | Complex I | Prevents the transfer of electrons from complex I to ubiquinone by blocking the ubiquinone-binding site. |

| Malonate and oxaloacetate | Poisons | Complex II | Competitive inhibitors of succinate dehydrogenase (complex II). |

| Antimycin A | Piscicide | Complex III | Binds to the Qi site of cytochrome c reductase, thereby inhibiting the oxidation of ubiquinol. |

Not all inhibitors of oxidative phosphorylation are toxins. In brown adipose tissue, regulated proton channels called uncoupling proteins can uncouple respiration from ATP synthesis. This rapid respiration produces heat, and is particularly important as a way of maintaining body temperature for hibernating animals, although these proteins may also have a more general function in cells' responses to stress.[93]

History

The field of oxidative phosphorylation began with the report in 1906 by Arthur Harden of a vital role for phosphate in cellular fermentation, but initially only sugar phosphates were known to be involved. However, in the early 1940s, the link between the oxidation of sugars and the generation of ATP was firmly established by Herman Kalckar, confirming the central role of ATP in energy transfer that had been proposed by Fritz Albert Lipmann in 1941. Later, in 1949, Morris Friedkin and Albert L. Lehninger proved that the coenzyme NADH linked metabolic pathways such as the citric acid cycle and the synthesis of ATP. The term oxidative phosphorylation was coined by Volodymyr Belitser in 1939.

For another twenty years, the mechanism by which ATP is generated

remained mysterious, with scientists searching for an elusive

"high-energy intermediate" that would link oxidation and phosphorylation

reactions. This puzzle was solved by Peter D. Mitchell with the publication of the chemiosmotic theory in 1961. At first, this proposal was highly controversial, but it was slowly accepted and Mitchell was awarded a Nobel prize in 1978. Subsequent research concentrated on purifying and characterizing the enzymes involved, with major contributions being made by David E. Green on the complexes of the electron-transport chain, as well as Efraim Racker on the ATP synthase. A critical step towards solving the mechanism of the ATP synthase was provided by Paul D. Boyer,

by his development in 1973 of the "binding change" mechanism, followed

by his radical proposal of rotational catalysis in 1982. More recent work has included structural studies on the enzymes involved in oxidative phosphorylation by John E. Walker, with Walker and Boyer being awarded a Nobel Prize in 1997.

![{\displaystyle {\ce {O2->[{\ce {e^{-}}}]{\underset {Superoxide}{O2^{\underline {\bullet }}}}->[{\ce {e^{-}}}]{\underset {Peroxide}{O2^{2-}}}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/a3d9bf9d3a61736aa6207fa53b8ce0165b9eebb6)