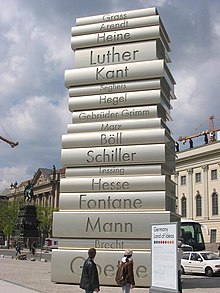

Birthday Book Printing, the fourth of the six Walk of Ideas sculptures displayed in Berlin during 2006, represents a pile of modern codex books.

The history of books starts with the development of writing, and various other inventions such as paper and printing, and continues through to the modern day business of book printing.

The earliest history of books actually predates what would

conventionally be called "books" today and begins with tablets, scrolls,

and sheets of papyrus. Then hand-bound, expensive, and elaborate books known as codices appeared. These gave way to press-printed

volumes and eventually lead to the mass printed tomes prevalent today.

Contemporary books may even have no physical presence with the advent of

the e-book. The book also became more accessible to the disabled with the advent of Braille and spoken books.

Clay tablets

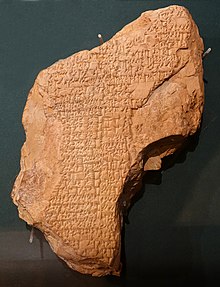

Sumerian clay tablet, currently housed in the Oriental Institute at the University of Chicago, inscribed with the text of the poem Inanna and Ebih by the priestess Enheduanna, the first author whose name is known

Clay tablets were used in Mesopotamia

in the 3rd millennium BC. The calamus, an instrument in the form of a

triangle, was used to make characters in moist clay. People used to use

fire to dry the tablets out. At Nineveh, over 20,000 tablets were found, dating from the 7th century BC; this was the archive and library of the kings of Assyria,

who had workshops of copyists and conservationists at their disposal.

This presupposes a degree of organization with respect to books,

consideration given to conservation, classification, etc. Tablets were

used right up until the 19th century in various parts of the world,

including Germany, Chile, Philippines and the Saharan Desert.

Cuneiform and Sumerian Writing

Writing originated as a form of record keeping in Sumer during the fourth millennium BCE with the advent of cuneiform.

Many clay tablets have been found that show cuneiform writing used to

record legal contracts, create lists of assets, and eventually to record

Sumerian literature and myths. Scribal schools have been found by

archaeologists from as early as the second millennium BCE where students

were taught the art of writing.

Papyrus

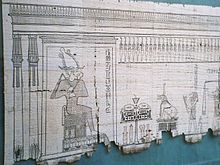

Egyptian Papyrus

After extracting the marrow from the stems of Papyrus reed, a

series of steps (humidification, pressing, drying, gluing, and cutting)

produced media of variable quality, the best being used for sacred

writing. In Ancient Egypt, papyrus was used as a medium for writing surfaces, maybe as early as from First Dynasty, but first evidence is from the account books of King Neferirkare Kakai of the Fifth Dynasty (about 2400 BC). A calamus, the stem of a reed sharpened to a point, or bird feathers were used for writing. The script of Egyptian scribes was called hieratic, or sacerdotal writing; it is not hieroglyphic,

but a simplified form more adapted to manuscript writing (hieroglyphs

usually being engraved or painted). Egyptians exported papyrus to other

Mediterranean civilizations including Greece and Rome where it was used

until parchment was developed.

Papyrus books were in the form of a scroll of several sheets pasted together, for a total length of 10 meters or more. Some books, such as the history of the reign of Ramses III,

were over 40 meters long. Books rolled out horizontally; the text

occupied one side, and was divided into columns. The title was indicated

by a label attached to the cylinder containing the book. Many papyrus

texts come from tombs, where prayers and sacred texts were deposited

(such as the Book of the Dead, from the early 2nd millennium BC).

East Asia

A Chinese bamboo book

Before the introduction of books, writing on bone, shells, wood and silk was prevalent in China long before the 2nd century BC, until paper

was invented in China around the 1st century AD. China's first

recognizable books, called jiance or jiandu, were made of rolls of thin

split and dried bamboo bound together with hemp, silk, or leather. The discovery of the process using the bark of the blackberry bush to create paper is attributed to Ts'ai Lun (the cousin of Kar-Shun), but it may be older. Texts were reproduced by woodblock printing;

the diffusion of Buddhist texts was a main impetus to large-scale

production. The format of the book evolved with intermediate stages of

scrolls folded concertina-style, scrolls bound at one edge ("butterfly books") and so on.

Although there is no exact date known, between 618 and 907 AD–The

period of the Tang Dynasty–the first printing of books started in

China. The oldest extant printed book is a work of the Diamond Sutra and dates back to 868 AD, during the Tang Dynasty. The Diamond Sutra was printed by method of woodblock printing,

a strenuous method in which the text to be printed would be carved into

a woodblock's surface, essentially to be used to stamp the words onto

the writing surface medium.

Woodblock printing was a common process for the reproduction of already

handwritten texts during the earliest stages of book printing. This

process was incredibly time-consuming.

Because of the meticulous and time-consuming process that woodblock printing was, Bi Sheng, a key contributor to the history of printing, invented the process of movable type printing (1041-1048 AD).

Bi Sheng developed a printing process in which written text could be

copied with the use of formed character types, the earliest types being

made of ceramic or clay material. The method of movable type printing would later become improved by Johannes Gutenberg.

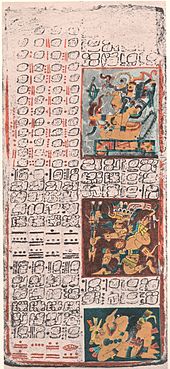

Pre-columbian codices of the Americas

Dresden Codex (page 49)

In Mesoamerica, information was recorded on long strips of paper,

agave fibers, or animal hides, which were then folded and protected by

wooden covers. These were thought to have existed since the time of the

Classical Period between the 3rd and 8th centuries, CE. Many of these

codices were thought to contain astrological information, religious

calendars, knowledge about the gods, genealogies of the rulers,

cartographic information, and tribute collection. Many of these codices

were stored in temples but were ultimately destroyed by the Spanish

explorers.

Currently, the only completely deciphered pre-Columbian writing system is the Maya script. The Maya, along with several other cultures in Mesoamerica, constructed concertina-style books written on Amate paper. Nearly all Mayan texts were destroyed by the Spanish during colonization on cultural and religious grounds. One of the few surviving examples is the Dresden Codex.

Although only the Maya have been shown to have a writing system

capable of conveying any concept that can be conveyed via speech (at

about the same level as the modern Japanese writing system), other Mesoamerican cultures had more rudimentary ideographical writing systems which were contained in similar concertina-style books, one such example being the Aztec codices.

Florentine Codex

There

are more than 2,000 illustrations drawn by native artists that

represent this era. Bernardino de Sahagun tells the story of Aztec

people’s lives and their natural history. The Florentine Codex speaks

about the culture religious cosmology and ritual practices, society,

economics, and natural history of the Aztec people. The manuscript are

arranged in both the Nahuatl language and in Spanish. The English

translation of the complete Nahuatl text of all twelve volumes of the

Florentine Codex took ten years. Arthur J.O. Anderson and Charles Dibble

had a decade of long work but made it an important contribution to

Mesoamerican ethnohistory. Years later, in 1979, the Mexican government

published a full-color volume of the Florentine Codex. Now, since 2012,

it is available digitally and fully accessible to those interested in

Mexican and Aztec History.

The Florentine Codex is a 16th century ethnographic research

study brought about by the Spanish Franciscan friar Bernardino de

Sahagun. The codex itself was actually named La Historia Universal de las Cosas de Nueva España.

Bernardino de Sahagun worked on this project from 1545 up until his

death in 1590. The Florentine Codex consist of twelve books. It is 2400

pages long but divided into the twelve books by categories such as; The

Gods, Ceremonies, Omens, and other cultural aspects of Aztec people.

Wax tablets

Romans used wax-coated wooden tablets or pugillares upon which they could write and erase by using a stylus.

One end of the stylus was pointed, and the other was spherical. Usually

these tablets were used for everyday purposes (accounting, notes) and

for teaching writing to children, according to the methods discussed by Quintilian in his Institutio Oratoria X Chapter 3. Several of these tablets could be assembled in a form similar to a codex. Also the etymology of the word codex (block of wood) suggest that it may have developed from wooden wax tablets.

Parchment

Parchment progressively replaced papyrus. Legend attributes its invention to Eumenes II, the king of Pergamon,

from which comes the name "pergamineum," which became "parchment." Its

production began around the 3rd century BC. Made using the skins of

animals (sheep, cattle, donkey, antelope, etc.), parchment proved to be

easier to conserve over time; it was more solid, and allowed one to

erase text. It was a very expensive medium because of the rarity of

material and the time required to produce a document. Vellum is the finest quality of parchment.

Greece and Rome

The scroll of papyrus

is called "volumen" in Latin, a word which signifies "circular

movement," "roll," "spiral," "whirlpool," "revolution" (similar,

perhaps, to the modern English interpretation of "swirl") and finally "a

roll of writing paper, a rolled manuscript, or a book."

In the 7th century Isidore of Seville explains the relation between codex, book and scroll in his Etymologiae (VI.13) as this:

| “ | A codex is composed of many books (librorum); a book is of one scroll (voluminis). It is called codex by way of metaphor from the trunks (caudex) of trees or vines, as if it were a wooden stock, because it contains in itself a multitude of books, as it were of branches. | ” |

Description

The

scroll is rolled around two vertical wooden axes. This design allows

only sequential usage; one is obliged to read the text in the order in

which it is written, and it is impossible to place a marker in order to

directly access a precise point in the text. It is comparable to modern

video cassettes. Moreover, the reader must use both hands to hold on

to the vertical wooden rolls and therefore cannot read and write at the

same time. The only volumen in common usage today is the Jewish Torah.

Book culture

The authors of Antiquity

had no rights concerning their published works; there were neither

authors' nor publishing rights. Anyone could have a text recopied, and

even alter its contents. Scribes earned money and authors earned mostly

glory, unless a patron provided cash; a book made its author famous.

This followed the traditional conception of the culture: an author stuck

to several models, which he imitated and attempted to improve. The

status of the author was not regarded as absolutely personal.

From a political and religious point of view, books were censored very early: the works of Protagoras were burned because he was a proponent of agnosticism

and argued that one could not know whether or not the gods existed.

Generally, cultural conflicts led to important periods of book

destruction: in 303, the emperor Diocletian ordered the burning of Christian texts. Some Christians

later burned libraries, and especially heretical or non-canonical

Christian texts. These practices are found throughout human history but

have ended in many nations today. A few nations today still greatly

censor and even burn books.

But there also exists a less visible but nonetheless effective

form of censorship when books are reserved for the elite; the book was

not originally a medium for expressive liberty. It may serve to confirm

the values of a political system, as during the reign of the emperor Augustus,

who skillfully surrounded himself with great authors. This is a good

ancient example of the control of the media by a political power.

However, private and public censorship have continued into the modern

era, albeit in various forms.

Proliferation and conservation of books in Greece

Little information concerning books in Ancient Greece

survives. Several vases (6th and 5th centuries BC) bear images of

volumina. There was undoubtedly no extensive trade in books, but there

existed several sites devoted to the sale of books.

The spread of books, and attention to their cataloging and conservation, as well as literary criticism developed during the Hellenistic period with the creation of large libraries in response to the desire for knowledge exemplified by Aristotle. These libraries were undoubtedly also built as demonstrations of political prestige:

- The Library of Alexandria, a library created by Ptolemy Soter and set up by Demetrius Phalereus (Demetrius of Phaleron). It contained 500,900 volumes (in the Museion section) and 40,000 at the Serapis temple (Serapeion). All books in the luggage of visitors to Egypt were inspected, and could be held for copying. The Museion was partially destroyed in 47 BC.

- The Library at Pergamon, founded by Attalus I; it contained 200,000 volumes which were moved to the Serapeion by Mark Antony and Cleopatra, after the destruction of the Museion. The Serapeion was partially destroyed in 391, and the last books disappeared in 641 CE following the Arab conquest.

- The Library at Athens, the Ptolemaion, which gained importance following the destruction of the Library at Alexandria ; the Library of Pantainos, around 100 CE; the library of Hadrian, in 132 CE.

- The Library at Rhodes, a library that rivaled the Library of Alexandria.

- The Library at Antioch, a public library of which Euphorion of Chalcis was the director near the end of the 3rd century.

The libraries had copyist workshops, and the general organization of books allowed for the following:

- Conservation of an example of each text

- Translation (the Septuagint Bible, for example)

- Literary criticisms in order to establish reference texts for the copy (example : The Iliad and The Odyssey)

- A catalog of books

- The copy itself, which allowed books to be disseminated

Book production in Rome

Book production developed in Rome

in the 1st century BC with Latin literature that had been influenced by

the Greek. Conservative estimates places the number of potential

readers in Imperial Rome at around 100,000 people.

This diffusion primarily concerned circles of literary individuals. Atticus was the editor of his friend Cicero. However, the book business progressively extended itself through the Roman Empire; for example, there were bookstores in Lyon. The spread of the book was aided by the extension of the Empire, which implied the imposition of the Latin tongue on a great number of people (in Spain, Africa, etc.).

Libraries were private or created at the behest of an individual. Julius Caesar, for example, wanted to establish one in Rome, proving that libraries were signs of political prestige.

In the year 377, there were 28 libraries in Rome, and it is known

that there were many smaller libraries in other cities. Despite the

great distribution of books, scientists do not have a complete picture

as to the literary scene in antiquity as thousands of books have been

lost through time.

Paper

Papermaking has traditionally been traced to China about AD 105, when Cai Lun, an official attached to the Imperial court during the Han Dynasty (202 BC – 220 AD), created a sheet of paper using mulberry and other bast fibres along with fishnets, old rags, and hemp waste.

While paper used for wrapping and padding was used in China since the 2nd century BC, paper used as a writing medium only became widespread by the 3rd century. By the 6th century in China, sheets of paper were beginning to be used for toilet paper as well. During the Tang Dynasty (618–907 AD) paper was folded and sewn into square bags to preserve the flavor of tea. The Song Dynasty (960–1279) that followed was the first government to issue paper currency.

An important development was the mechanization of paper manufacture by medieval papermakers. The introduction of water-powered paper mills, the first certain evidence of which dates to the 11th century in Córdoba, Spain, allowed for a massive expansion of production and replaced the laborious handcraft characteristic of both Chinese and Muslim

papermaking. Papermaking centres began to multiply in the late 13th

century in Italy, reducing the price of paper to one sixth of parchment and then falling further.

Middle Ages

The codex Manesse, a book from the Middle Ages

By the end of antiquity, between the 2nd and 4th centuries, the scroll was replaced by the codex.

The book was no longer a continuous roll, but a collection of sheets

attached at the back. It became possible to access a precise point in

the text quickly. The codex is equally easy to rest on a table, which

permits the reader to take notes while he or she is reading. The codex

form improved with the separation of words, capital letters, and

punctuation, which permitted silent reading. Tables of contents and

indices facilitated direct access to information. This form was so

effective that it is still the standard book form, over 1500 years after

its appearance.

Paper would progressively replace parchment. Cheaper to produce, it allowed a greater diffusion of books.

Books in monasteries

A number of Christian books were destroyed at the order of Diocletian

in 304 AD. During the turbulent periods of the invasions, it was the

monasteries that conserved religious texts and certain works of Antiquity for the West. But there would also be important copying centers in Byzantium.

The role of monasteries in the conservation of books is not without some ambiguity:

- Reading was an important activity in the lives of monks, which can be divided into prayer, intellectual work, and manual labor (in the Benedictine order, for example). It was therefore necessary to make copies of certain works. Accordingly, there existed scriptoria (the plural of scriptorium) in many monasteries, where monks copied and decorated manuscripts that had been preserved.

- However, the conservation of books was not exclusively in order to preserve ancient culture; it was especially relevant to understanding religious texts with the aid of ancient knowledge. Some works were never recopied, having been judged too dangerous for the monks. Moreover, in need of blank media, the monks scraped off manuscripts, thereby destroying ancient works. The transmission of knowledge was centered primarily on sacred texts.

Copying and conserving books

An author portrait of Jean Miélot writing his compilation of the Miracles of Our Lady, one of his many popular works.

Despite this ambiguity, monasteries in the West and the Eastern

Empire permitted the conservation of a certain number of secular texts,

and several libraries were created: for example, Cassiodorus ('Vivarum' in Calabria, around 550), or Constantine I in Constantinople.

There were several libraries, but the survival of books often depended

on political battles and ideologies, which sometimes entailed massive

destruction of books or difficulties in production (for example, the

distribution of books during the Iconoclasm between 730 and 842). A long list of very old and surviving libraries that now form part of the Vatican Archives can be found in the Catholic Encyclopedia.

A very strong example of the early copying and conserving books is that of the Quran.

After Muhammad, his companion Abu Bakr, on the recommendation of Umar

Bin Alkhattab, assigned Zayd bin Saabit to compile the first official

scripture of the Quran. Zayd collected all the available scriptures of

the Quran scripted by different companions of Muhammad during his life.

He compiled one scripture and got it verified by all the companions who

had memorized the whole book while Muhammad was alive. Then this first

official scripture was kept at the house of Hafsa, the wife of the

Muhammad. By the time of the third caliph Uthmaan, the Islamic state had

spread over a large portion of the known world. He ordered the

preparation of the official copies of the first official scripture. The

copies were duly verified for accuracy. These copies were sent to each

city of the caliphate so that further copies can be made locally with

the perfect accuracy.

To help preserve books and protect them from thieves, librarians would create chained libraries.

Chained Libraries were books displayed next to each other to create a

tight bond. This eliminated unauthorised removal of books. One of the

earliest chained libraries was in England during the 1500s. Popular

culture also has examples of chained libraries, such as in Harry Potter and the Philosopher's Stone by J.K Rowling.

The scriptorium

The

scriptorium was the workroom of monk copyists; here, books were copied,

decorated, rebound, and conserved. The armarius directed the work and

played the role of librarian.

The role of the copyist was multifaceted: for example, thanks to

their work, texts circulated from one monastery to another. Copies also

allowed monks to learn texts and to perfect their religious education.

The relationship with the book thus defined itself according to an

intellectual relationship with God. But if these copies were sometimes made for the monks themselves, there were also copies made on demand.

The task of copying itself had several phases: the preparation of

the manuscript in the form of notebooks once the work was complete, the

presentation of pages, the copying itself, revision, correction of

errors, decoration, and binding. The book therefore required a variety of competencies, which often made a manuscript a collective effort.

Transformation from the literary edition in the 12th century

The scene in Botticelli's Madonna of the Book (1480) reflects the presence of books in the houses of richer people in his time.

The revival of cities in Europe would change the conditions of book

production and extend its influence, and the monastic period of the book

would come to an end. This revival accompanied the intellectual

renaissance of the period. The Manuscript culture

outside of the monastery developed in these university-cities in Europe

in this time. It is around the first universities that new structures

of production developed: reference manuscripts were used by students and

professors for teaching theology

and liberal arts. The development of commerce and of the bourgeoisie

brought with it a demand for specialized and general texts (law,

history, novels, etc.). It is in this period that writing in the common

vernacular developed (courtly poetry, novels, etc.). Commercial

scriptoria became common, and the profession of book seller came into

being, sometimes dealing internationally.

There is also the creation of royal libraries as in the case of Saint Louis and Charles V. Books were also collected in private libraries, which became more common in the 14th and 15th centuries.

The use of paper diffused through Europe in the 14th century. This material, less expensive than parchment, came from China via the Arabs in Spain in the 11th and 12th centuries. It was used in particular for ordinary copies, while parchment was used for luxury editions.

Printing press

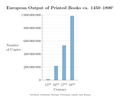

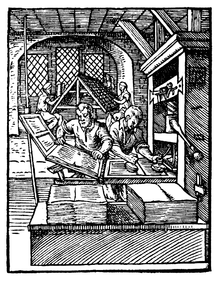

The invention of the moveable type on the printing press by Johann Fust, Peter Schoffer and Johannes Gutenberg

around 1440 marks the entry of the book into the industrial age. The

Western book was no longer a single object, written or reproduced by

request. The publication of a book became an enterprise, requiring

capital for its realization and a market for its distribution. The cost

of each individual book (in a large edition) was lowered enormously,

which in turn increased the distribution of books. The book in codex

form and printed on paper, as we know it today, dates from the 15th

century. Books printed before January 1, 1501, are called incunables. The spreading of book printing all over Europe occurred relatively quickly, but most books were still printed in Latin. The spreading of the concept of printing books in the vernacular was a somewhat slower process.

List of notable printing milestones

Jikji, Selected Teachings of Buddhist Sages and Seon Masters, the earliest known book printed with movable metal type, 1377. Bibliothèque Nationale de France, Paris.

Handwritten notes by Christopher Columbus on the Latin edition of Marco Polo's Le livre des merveilles.

First printed book in Georgian was published in Rome, in 1629 by Niceforo Irbachi.

- 1377: Jikji is known to be the first printed book using movable metal print technology by Koryo (Korea). Jikji is abbreviated title of a Korean Buddhist document, Selected Teachings of Buddhist Sages and Seon Masters.

- 1455: The Gutenberg Bible (in Latin) was the first major book printed in Europe with movable metal type by Johannes Gutenberg.

- 1461: Der Ackermann aus Böhmen printed by Albrecht Pfister, the first printed book in German, and also the first book illustrated with woodcuts.

- 1470: Il Canzoniere by Francesco Petrarca, the first book printed in the Italian language.

- 1472: Sinodal de Aguilafuente was the first book printed in Spain (at Segovia) and in the Spanish language.

- 1473: Chronica Hungarorum was the first book printed in Hungary. It was printed by Andreas Hess in Buda.

- 1474: Obres e trobes en llaor de la Verge Santa Maria was the first book printed in the Valencian language, at Valencia.

- c. 1475: Recuyell of the Historyes of Troye was the first book printed in the English language.

- 1476: La légende dorée printed by Guillaume LeRoy, the first book printed in the French language.

- 1476: Aristotle's De Animalibus, the first printed compilation of works on biology, (translated from the Greek) was printed in Venice, the basis of medical education for 1600 years prior: not to be confused with Albertus Magnus's version, translated from Arabic by Michael Scot.[32]

- 1476: Grammatica Graeca, sive compendium octo orationis partium, probably the first book entirely in Greek, by Constantine Lascaris.

- 1477: The first printed edition of Geographia by Ptolemy, probably in 1477 in Bologna, was also the first printed book with engraved illustrations.

- 1477: The Delft Bible, the first book printed in the Dutch language.

- 1482: Euclid's Elements the first printed version (by Erhard Ratdolt), was the basis of mathematical education for 1600 years prior.

- 1483: Misal po zakonu rimskoga dvora, the first book printed in the Croatian language and in Glagolitic alphabet.

- 1485: De Re Aedificatoria, the first printed book on architecture

- 1487: "Pentateuco", the first book printed in Portugal, in Hebraic language, by the Jew Samuel Gacon in Vila-a-Dentro, Faro.

- 1494: Oktoih was the first printed Slavic Cyrillic book.

- 1495: The first printed book in the Danish language.

- 1495: The first printed book in the Swedish language.

- 1497: "Constituições que fez o Senhor Dom Diogo de Sousa, Bispo do Porto", first book printed in the Portuguese language, by the first Portuguese printer, Rodrigo Álvares, in Porto, on January the 4th.

- 1499: Catholicon, Breton-French-Latin dictionary, first printed trilingual dictionary, first Breton book, first French dictionary

- 1501: Harmonice Musices Odhecaton, printed by Ottaviano Petrucci, is the first book of sheet music printed from movable type.

- 1501: Aldus Manutius printed the first portable Octavos, also inventing and using italic type.

- 1508: Chepman and Myllar printed the first books in Scotland.

- 1511: Hieromonk Makarije printed the first books in Wallachia (in Slavonic)

- 1512: Hakob Meghapart printed the first book in Armenian – Urbatagirk.[33]

- 1513: Hortulus Animae, polonice believed to be the first book printed in the Polish language.

- 1516: A reprint of the Lisbon edition of the Sefer Aburdraham is printed in Morocco, the first book printed in Africa.

- 1517: Psalter, first book printed in the Old Belarusian language by Francysk Skaryna on 6 August 1517

- 1539: La escala espiritual de San Juan Clímaco, first book printed in North America – Mexico

- 1541: Bovo-Bukh was the first non-religious book to be printed in Yiddish

- 1544: Rucouskiria by Mikael Agricola, the first book printed in the Finnish language.

- 1545: Linguae Vasconum Primitiae was the first book printed in Basque

- 1547: Martynas Mažvydas compiled and published the first printed Lithuanian book The Simple Words of Catechism

- 1550: Catechismus by Primož Trubar was the first book written in the Slovene language.

- 1561: The first printed books in the Romanian language, Tetraevanghelul and Întrebare creştinească (also known as Catehismul) are printed by Coresi in Braşov.

- 1564: The first book in Irish was printed in Edinburgh, a translation of John Knox's 'Liturgy' by John Carswell, Bishop of the Hebrides.

- 1564: The first dated Russian book, Apostol, printed by Ivan Fyodorov

- 1567: Foirm na n-Urrnuidheadh, the Gaelic translation of the Book of Common Order by John Carswell, the first work to be printed in any Goidelic language

- 1571: The first book in Irish to be printed in Ireland was a Protestant catechism (Aibidil Gaoidheilge agus Caiticiosma), containing a guide to spelling and sounds in Irish.[35]

- 1577: Lekah Tov, a commentary on the Book of Esther, was the first book printed in what is now Israel

- 1581: Ostrog Bible, first complete printed edition of the Bible in Old Church Slavonic

- 1584: first book printed in South America – Lima, Peru

- 1593: Doctrina Christiana was the first book printed in the Philippines

- 1629: Nikoloz Cholokashvili helped to publish a Georgian dictionary, the first printed book in Georgian

- 1640: The Bay Psalm Book, the first book printed in British North America

- 1651: Abagar – Filip Stanislavov, first printed book in modern Bulgarian

- 1678–1703: Hortus Malabaricus included the first instance of Malayalam types being used for printing

- 1798: The first printed book in Ossetic

- 1802: New South Wales General Standing Orders was the first book printed in Australia, comprising Government and General Orders issued between 1791 and 1802

- 1908-09: Aurora Australis, the first book published in Antarctica, by members of Ernest Shackleton's expedition.

Contemporary era

During the Enlightenment

more books began to pour off European presses, creating an early form

of information overload for many readers. Nowhere was this more the

case than in Enlightenment Scotland, where students were exposed to a

wide variety of books during their education. The demands of the British and Foreign Bible Society (founded 1804), the American Bible Society

(founded 1816), and other non-denominational publishers for enormously

large inexpensive runs of texts led to numerous innovations. The

introduction of steam printing presses a little before 1820, closely

followed by new steam paper mills, constituted the two most major

innovations. Together, they caused book prices to drop and the number

of books to increase considerably. Numerous bibliographic features,

like the positioning and formulation of titles and subtitles, were also

affected by this new production method. New types of documents appeared

later in the 19th century: photography, sound recording and film.

Typewriters and eventually computer based word processors and printers let people print and put together their own documents. Desktop publishing is common in the 21st century.

Among a series of developments that occurred in the 1990s, the

spread of digital multimedia, which encodes texts, images, animations,

and sounds in a unique and simple form was notable for the book

publishing industry. Hypertext further improved access to information. Finally, the internet lowered production and distribution costs.

E-books and the future of the book

It is difficult to predict the future of the book in an era of fast-paced technological change.

Anxieties about the "death of books" have been expressed throughout the

history of the medium, perceived as threatened by competing media such

as radio, television, and the Internet.

However, these views are generally exaggerated, and "dominated by

fetishism, fears about the end of humanism and ideas of

techno-fundamentalist progress". The print book medium has proven to be very resilient and adaptable.

A good deal of reference material, designed for direct access instead of sequential reading, as for example encyclopedias,

exists less and less in the form of books and increasingly on the web.

Leisure reading materials are increasingly published in e-reader

formats.

Although electronic books, or e-books, had limited success in the

early years, and readers were resistant at the outset, the demand for

books in this format has grown dramatically, primarily because of the

popularity of e-reader devices and as the number of available titles in

this format has increased. Since the Amazon Kindle

was released in 2007, the e-book has become a digital phenomenon and

many theorize that it will take over hardback and paper books in future.

E-books are much more accessible and easier to buy and it’s also

cheaper to purchase an E-Book rather than its physical counterpart due

to paper expenses being deducted.

Another important factor in the increasing popularity of the e-reader

is its continuous diversification. Many e-readers now support basic

operating systems, which facilitate email and other simple functions.

The iPad is the most obvious example of this trend, but even mobile phones can host e-reading software.

Reading for the blind

Braille

is a system of reading and writing through the use of the finger tips.

Braille was developed as a system of efficient communication for blind

and partially blind alike.

The system consists of sixty-three characters and is read left to

right. These characters are made with small raised dots in two columns

similar to a modern domino piece to represent each letter.

Readers can identify characters with two fingers. Reading speed

averages one hundred and twenty-five words per minute and can reach two

hundred words per minute.

The making of Braille

Braille was named after its creator Louis Braille in 1824 in France. Braille stabbed himself in the eyes at the age of three with his father's leather working tools. Braille spent nine years working on a previous system of communication called night writing by Charles Barbier. Braille published his book "procedure for writing words, music, and plainsong in dots", in 1829. In 1854 France made Braille the "official communication system for blind individuals". Valentin Haüy was the first person to put Braille on paper in the form of a book. In 1932 Braille became accepted and used in English speaking countries.

In 1965 the Nemeth Code of Braille Mathematics and Scientific Notation

was created. The code was developed to assign symbols to advanced

mathematical notations and operations. The system has remained the same, only minor adjustments have been made to it since its creation.

Spoken books

The

spoken book was originally created in the 1930s to provide the blind

and visually impaired with a medium to enjoy books. In 1932 the American Foundation for the Blind created the first recordings of spoken books on vinyl records. In 1935, a British based foundation, Royal National Institute for the Blind (RNIB), was the first to deliver talking books to the blind on vinyl records. Each record contained about thirty minutes of audio on both sides, and the records were played on a gramophone. Spoken books changed mediums in the 1960s with the transition from vinyl records to cassette tapes.

The next progression of spoken books came in the 1980s with the

widespread use of compact discs. Compact discs reached more people and

made it possible to listen to books in the car. In 1995 the term audiobook became the industry standard.

Finally, the internet enabled audiobooks to become more accessible and

portable. Audiobooks could now be played in their entirety instead of

being split onto multiple disks.

Academic discipline

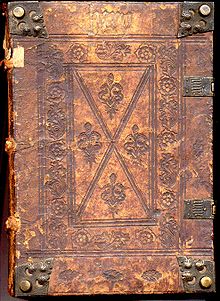

A 15th-century Incunable. Notice the blind-tooled cover, corner bosses and clasps.

The history of the book as an academic discipline studies the production, transmission, circulation and dissemination of text from antiquity to the present day. Its scope includes the book as object, the history of ideas, history of religion, bibliography, conservation, curation and the future of the book.

Origins

The history of the book came into existence in the latter half of the 20th century. It was fostered by William Ivins Jr.'s Prints and Visual Communication (1953) and Henri-Jean Martin and Lucien Febvre's L'apparition du livre (The Coming of the Book: The Impact of Printing, 1450–1800) in 1958 as well as Marshall McLuhan's Gutenberg Galaxy: The Making of Typographic Man (1962). Another notable pioneer in the History of the Book is Robert Darnton.