High Middle Ages

Europe and Mediterranean region

Europe and Mediterranean region

Europe and the Mediterranean region, c. 1190

|

|

- The Crusades

- (Solid Line) Second Crusade of Louis VII and Conrad III

- (Line and dot) Third Crusade of Richard I, Phillip II, and Fredrick I

Key historical trends of the High Middle Ages include the rapidly increasing population of Europe, which brought about great social and political change from the preceding era, and the Renaissance of the 12th century, including the first developments of rural exodus and of urbanization. By 1250, the robust population increase had greatly benefited the European economy, which reached levels that would not be seen again in some areas until the 19th century. That trend faltered during the Late Middle Ages because of a series of calamities, most notably the Black Death, but also numerous wars as well as economic stagnation.

From around 780, Europe saw the last of the barbarian invasions and became more socially and politically organized. The Carolingian Renaissance led to scientific and philosophical activity in Northern Europe. The first universities started operating in Bologna, Paris, Oxford and Modena. The Vikings settled in the British Isles, France and elsewhere, and Norse Christian kingdoms started developing in their Scandinavian homelands. The Magyars ceased their expansion in the 10th century, and by the year 1000, a Christian Kingdom of Hungary had become a recognized state in Central Europe that was forming alliances with regional powers. With the brief exception of the Mongol invasions in the 13th century, major nomadic incursions ceased. The powerful Byzantine Empire of the Macedonian and the Komnenos dynasties gradually gave way to the resurrected Serbia and Bulgaria and to a successor crusader state (1204 to 1261), which countered the continuous threat of the Seljuk Turks in Asia Minor.

In the 11th century, populations north of the Alps began a more intensive settlement, targeting "new" lands, some of which areas had reverted to wilderness after the end of the Roman Empire. In what is known as the "great clearances", Europeans cleared and cultivated some of the vast forests and marshes that lay across of the continent. At the same time, some settlers moved beyond the traditional boundaries of the Frankish Empire to new frontiers beyond the Elbe River, which tripled the size of Germany in the process. The Catholic Church, which reached the peak of its political power around then, called armies from across Europe to a series of Crusades against the Seljuk Turks. The crusaders occupied the Holy Land and founded the Crusader States in the Levant. Other wars led to the Northern Crusades. The Christian kingdoms took much of the Iberian Peninsula from Muslim control, and the Normans conquered southern Italy, all part of the major population increases and the resettlement patterns of the era.

The High Middle Ages produced many different forms of intellectual, spiritual and artistic works. The age also saw the rise of ethnocentrism, which evolved later into modern civic nationalisms in most of Europe, the ascent of the great Italian city-states and the rise and fall of the Muslim civilization of Al-Andalus. The rediscovery of the works of Aristotle led Thomas Aquinas and other thinkers of the period to expand Scholasticism, a combination of Catholicism and ancient philosophy. For much of this period, Constantinople remained Europe's most populous city, and Byzantine art reached a peak in the 12th century. In architecture, many of the most notable Gothic cathedrals were built or completed around this period.

The Crisis of the Late Middle Ages began at the start of the 14th century and marked the end of the period.

Historical events and politics

Bayeux Tapestry depicting the Battle of Hastings during the Norman invasion of England

Great Britain and Ireland

The painted effigies of Eleanor of Aquitaine and Henry II of England from the Fontevraud Abbey in Anjou, France, which no longer houses their remains

In England, the Norman Conquest of 1066 resulted in a kingdom ruled by a Francophone nobility. The Normans

invaded Ireland by force in 1169 and soon established themselves

throughout most of the country, although their stronghold was the

southeast. Likewise, Scotland and Wales

were subdued to vassalage at about the same time, though Scotland later

asserted its independence and Wales remained largely under the rule of

independent native princes until the death of Llywelyn ap Gruffydd in 1282. The Exchequer was founded in the 12th century under King Henry I, and the first parliaments were convened. In 1215, after the loss of Normandy, King John signed the Magna Carta into law, which limited the power of English monarchs.

Spain and Italy

Much of the Iberian peninsula had been occupied by the Moors

after 711, although the northernmost portion was divided between

several Christian states. In the 11th century, and again in the

thirteenth, the Christian kingdoms of the north gradually drove the

Muslims from central and most of southern Iberia.

In Italy, independent city states grew affluent on eastern maritime trade. These were in particular the thalassocracies of Pisa, Amalfi, Genoa and Venice.

The Pontic steppes, c. 1015

From the mid-tenth to the mid-11th centuries, the Scandinavian kingdoms were unified and Christianized, resulting in an end of Viking raids, and greater involvement in European politics. King Cnut

of Denmark ruled over both England and Norway. After Cnut's death in

1035, England and Norway were lost, and with the defeat of Valdemar II in 1227, Danish predominance in the region came to an end. Meanwhile, Norway extended its Atlantic possessions, ranging from Greenland to the Isle of Man, while Sweden, under Birger Jarl, built up a power-base in the Baltic Sea. However, the Norwegian influence started to decline already in the same period, marked by the Treaty of Perth of 1266. Also, civil wars raged in Norway between 1130 and 1240.

France and Germany

By the time of the High Middle Ages, the Carolingian Empire

had been divided and replaced by separate successor kingdoms called

France and Germany, although not with their modern boundaries. Germany

was under the banner of the Holy Roman Empire, which reached its high-water mark of unity and political power.

Georgia

During the successful reign of King David IV of Georgia (1089–1125), Kingdom of Georgia grew in strength and expelled the Seljuk Empire from its lands. David's decisive victory in the Battle of Didgori (1121) against the Seljuk Turks, as a result of which Georgia recaptured its lost capital Tbilisi, marked the beginning of the Georgian Golden Age. David's granddaughter Queen Tamar

continued the upward rise, successfully neutralizing internal

opposition and embarking on an energetic foreign policy aided by further

decline of the hostile Seljuk Turks.

Relying on a powerful military élite, Tamar was able to build on the

successes of her predecessors to consolidate an empire which dominated

vast lands spanning from present-day southern Russia on the Black Sea to the Caspian Sea. Georgia remained a leading regional power until its collapse under the Mongol attacks within two decades after Tamar's death.

Hungary

King Saint Stephen I of Hungary.

In the High Middle Ages, the Kingdom of Hungary (founded in 1000), became one of the most powerful medieval states in central Europe and Western Europe. King Saint Stephen I of Hungary

introduced Christianity to the region; he was remembered by the

contemporary chroniclers as a very religious monarch, with wide

knowledge in Latin grammar, strict with his own people but kind to the

foreigners. He eradicated the remnants of the tribal organization in the

Kingdom and forced the people to sedentarize and adopt the Christian

religion, ethics, way of life and founded the Hungarian medieval state,

organising it politically in counties using the Germanic system as a

model.

The following monarchs usually kept a close relationship with Rome like Saint Ladislaus I of Hungary, and a tolerant attitude with the pagans that escaped to the Kingdom searching for sanctuary (for example Cumans in the 13th century), which eventually created certain discomfort for some Popes. With entering in Personal union with the Kingdom of Croatia and annexation of other small states, Hungary became a small empire that extended its control over the Balkans and all the Carpathian region. The Hungarian royal house was the one that gave the most saints to the Catholic Church during medieval times.

Poland and Lithuania

During the High Middle Ages Poland emerged as a kingdom. It decided to bond itself with the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, confirmed by the Union of Krewo and later treaties, leading to a personal union in 1569.

Southeastern Europe

The High Middle Ages saw the height and decline of the Slavic state of Kievan Rus' and emergence of Cumania. Later, the Mongol invasion in the 13th century had great impact on the east of Europe, as many countries of the region were invaded, pillaged, conquered and/or vassalized.

During the first half of this period (c. 1025—1185) the Byzantine Empire dominated the Balkans, and under the Komnenian emperors there was a revival of prosperity and urbanization; however, their domination of Southeastern Europe came to an end with a successful Vlach-Bulgarian rebellion in 1185, and henceforth the region was divided between the Byzantines in Greece, some parts of Macedonia, and Thrace, the Bulgarians in Moesia and most of Thrace and Macedonia, and the Serbs

to the northwest. Eastern and Western churches had formally split in

the 11th century, and despite occasional periods of co-operation during

the 12th century, in 1204 the Fourth Crusade treacherously captured Constantinople. This severely damaged the Byzantines, and their power was ultimately weakened by the Seljuks and the rising Ottoman Empire in the 14–15th century. The power of the Latin Empire, however, was short lived after the Crusader army was routed by Bulgarian Emperor Kaloyan in the Battle of Adrianople (1205).

Climate and agriculture

The Medieval Warm Period,

the period from 10th century to about the 14th century in Europe, was a

relatively warm and gentle interval ended by the generally colder Little Ice Age. Farmers grew wheat well north into Scandinavia, and wine

grapes in northern England, although the maximum expansion of vineyards

appears to occur within the Little Ice Age period. During this time, a

high demand for wine and steady volume of alcohol consumption inspired a

viticulture revolution of progress. This protection from famine

allowed Europe's population to increase, despite the famine in 1315

that killed 1.5 million people. This increased population contributed to

the founding of new towns and an increase in industrial and economic

activity during the period. They also established trade and a

comprehensive production of alcohol. Food production also increased

during this time as new ways of farming were introduced, including the

use of a heavier plow, horses instead of oxen, and a three-field system

that allowed the cultivation of a greater variety of crops than the

earlier two-field system—notably legumes, the growth of which prevented the depletion of important nitrogen from the soil.

The rise of chivalry

Household heavy cavalry (knights) became common in the 11th century across Europe, and tournaments

were invented. Although the heavy capital investment in horse and armor

was a barrier to entry, knighthood became known as a way for serfs to

earn their freedom. In the 12th century, the Cluny monks promoted ethical warfare and inspired the formation of orders of chivalry, such as the Templar Knights. Inherited titles of nobility were established during this period. In 13th-century Germany, knighthood became another inheritable title, although one of the less prestigious, and the trend spread to other countries.

Religion

Christian Church

The East–West Schism of 1054 formally separated the Christian church into two parts: Western Catholicism in Western Europe and Eastern Orthodoxy in the east. It occurred when Pope Leo IX and Patriarch Michael I excommunicated each other, mainly over disputes as to the existence of papal authority over the four Eastern patriarchs, as well as disagreement over the filioque.

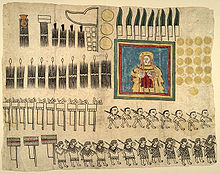

Crusades

The Crusades occurred between the 11th and 13th centuries. They were

conducted under papal authority with the intent of reestablishing

Christian rule in The Holy Land by taking the area from the Muslim Fatimid Caliphate. The Fatimids had captured Palestine in AD 970, lost it to the Seljuk Turks in 1073 and recaptured it in 1098, just before they lost it again in 1099 as a result of the First Crusade.

Military orders

In the context of the crusades, monastic military orders were founded that would become the template for the late medieval chivalric orders.

The Knights Templar were a Christian military order founded after the First Crusade

to help protect Christian pilgrims from hostile locals and highway

bandits. The order was deeply involved in banking, and in 1307 Philip the Fair (Philippine le Bel) had the entire order arrested in France and dismantled on charges of heresy.

The Knights Hospitaller were originally a Christian organization founded in Jerusalem in 1080 to provide care for poor, sick, or injured pilgrims to the Holy Land. After Jerusalem was taken in the First Crusade, it became a religious/military order

that was charged with the care and defence of the Holy Lands. After the

Holy Lands were eventually taken by Muslim forces, it moved its

operations to Rhodes, and later Malta.

The Teutonic Knights were a German religious order formed in 1190, in the city of Acre, to both aid Christian pilgrims on their way to the Holy Lands and to operate hospitals for the sick and injured in Extremer. After Muslim forces captured the Holy Lands, the order moved to Transylvania in 1211 and later, after being expelled, invaded pagan Prussic with the intention of Christianizing the Baltic region. Yet, before and after the Order's main pagan opponent, Lithuania, converted to Christianity, the Order had already attacked other Christian nations such as Novgorod and Poland. The Teutonic Knights' power hold, which became considerable, was broken in 1410, at the Battle of Grunwald,

where the Order suffered a devastating defeat against a joint

Polish-Lithuanian army. After Grunwald, the Order declined in power

until 1809 when it was officially dissolved. There were ten crusades in

total.

Scholasticism

The new Christian method of learning was influenced by Anselm of Canterbury (1033–1109) from the rediscovery of the works of Aristotle, at first indirectly through Medieval Jewish and Muslim Philosophy (Maimonides, Avicenna, and Averroes) and then through Aristotle's own works brought back from Byzantine and Muslim libraries; and those whom he influenced, most notably Albertus Magnus, Bonaventure and Abélard. Many scholastics believed in empiricism and supporting Roman Catholic doctrines through secular study, reason, and logic. They opposed Christian mysticism, and the Platonist-Augustinian belief that the mind is an immaterial substance. The most famous of the scholastics was Thomas Aquinas (later declared a "Doctor of the Church"), who led the move away from the Platonic and Augustinian and towards Aristotelianism. Aquinas developed a philosophy of mind by writing that the mind was at birth a tabula rasa

("blank slate") that was given the ability to think and recognize forms

or ideas through a divine spark. Other notable scholastics included Roscelin, Abélard, Peter Lombard, and Francisco Suárez. One of the main questions during this time was the problem of universals. Prominent opponents of various aspects of the scholastic mainstream included Duns Scotus, William of Ockham, Peter Damian, Bernard of Clairvaux, and the Victorines.

Golden age of monasticism

- The late 11th century/early-mid 12th century was the height of the golden age of Christian monasticism (8th-12th centuries).

- Benedictine Order – black-robed monks

- Cistercian Order – white-robed monks

Mendicant orders

- The 13th century saw the rise of the Mendicant orders such as the:

- Franciscans (Friars Minor, commonly known as the Grey Friars), founded 1209

- Carmelites (Hermits of the Blessed Virgin Mary of Carmel, commonly known as the White Friars), founded 1206–1214

- Dominicans (Order of Preachers, commonly called the Black Friars), founded 1215

- Augustinians (Hermits of St. Augustine, commonly called the Austin Friars), founded 1256

Heretical movements

Christian heresies

existed in Europe before the 11th century but only in small numbers and

of local character: in most cases, a rogue priest, or a village

returning to pagan traditions. Beginning in the 11th century, however

mass-movement heresies appeared. The roots of this can be partially

sought in the rise of urban cities, free merchants, and a new

money-based economy. The rural values of monasticism held little appeal

to urban people who began to form sects more in tune with urban culture.

The first large-scale heretical movements in Western Europe originated

in the newly urbanized areas such as southern France and northern Italy

and were probably influenced by the Bogomils and other dualist movements.

These heresies were on a scale the Catholic Church had never seen

before; the response was one of elimination for some (such as the Cathars), and acceptance and integration of others (such as the veneration of Francis of Assisi, the son of an urban merchant who renounced money).

Cathars

Cathars being expelled from Carcassonne in 1209

Catharism was a movement with Gnostic elements that originated around the middle of the 10th century, branded by the contemporary Roman Catholic Church as heretical. It existed throughout much of Western Europe, but its origination was in Languedoc and surrounding areas in southern France.

The name Cathar stems from Greek katharos, "pure". One of the first recorded uses is Eckbert von Schönau who wrote on heretics from Cologne in 1181: "Hos nostra Germania catharos appellat."

The Cathars are also called Albigensians. This name originates from the end of the 12th century, and was used by the chronicler Geoffroy du Breuil of Vigeois in 1181. The name refers to the southern town of Albi (the ancient Albiga). The designation is hardly exact, for the centre was at Toulouse and in the neighboring districts.

The Albigensians were strong in southern France, northern Italy, and the southwestern Holy Roman Empire.

The Bogomils were strong in the Balkans, and became the official religion supported by the Bosnian kings.

- Dualists believed that historical events were the result of struggle between a good force and an evil force and that evil ruled the world, though it could be controlled or defeated through asceticism and good works.

- Albigensian Crusade, Simon de Montfort, Montségur, Château de Quéribus

Waldensians

Peter Waldo of Lyon was a wealthy merchant who gave up his riches around 1175 after a religious experience and became a preacher. He founded the Waldensians

which became a Christian sect believing that all religious practices

should have scriptural basis. Waldo was denied the right to preach his

sermons by the Third Lateran Council in 1179, which he did not obey and

continued to speak freely until he was excommunicated in 1184. Waldo was

critical of the Christian clergy saying they did not live according to

the word. He rejected the practice of selling indulgences, as well as

the common saint cult practices of the day.

Waldensians are considered a forerunner to the Protestant Reformation, and they melted into Protestantism with the outbreak of the Reformation and became a part of the wider Reformed tradition after the views of John Calvin and his theological successors in Geneva proved very similar to their own theological thought. Waldensian churches still exist, located on several continents.

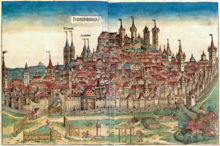

Trade and commerce

In Northern Europe, the Hanseatic League, a federation of free cities to advance trade by sea, was founded in the 12th century, with the foundation of the city of Lübeck, which would later dominate the League, in 1158–1159. Many northern cities of the Holy Roman Empire became hanseatic cities, including Amsterdam, Cologne, Bremen, Hanover and Berlin. Hanseatic cities outside the Holy Roman Empire were, for instance, Bruges and the Polish city of Gdańsk (Danzig), as well as Königsberg, capital of the monastic state of the Teutonic Knights. In Bergen, Norway and Veliky Novgorod, Russia the league had factories and middlemen. In this period the Germans started colonizing Europe beyond the Empire, into Prussia and Silesia.

In the late 13th century, a Venetian explorer named Marco Polo became one of the first Europeans to travel the Silk Road to China. Westerners became more aware of the Far East when Polo documented his travels in Il Milione. He was followed by numerous Christian missionaries to the East, such as William of Rubruck, Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, André de Longjumeau, Odoric of Pordenone, Giovanni de' Marignolli, Giovanni di Monte Corvino, and other travellers such as Niccolò de' Conti.

Science

Philosophical and scientific teaching of the Early Middle Ages was based upon few copies and commentaries of ancient Greek texts that remained in Western Europe after the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. Most of them were studied only in Latin as knowledge of Greek was very limited.

This scenario changed during the Renaissance of the 12th century. The intellectual revitalization of Europe started with the birth of medieval universities. The increased contact with the Islamic world in Spain and Sicily during the Reconquista, and the Byzantine world and Muslim Levant during the Crusades, allowed Europeans access to scientific Arabic and Greek texts, including the works of Aristotle, Alhazen, and Averroes. The European universities aided materially in the translation and propagation of these texts and started a new infrastructure which was needed for scientific communities.

At the beginning of the 13th century there were reasonably accurate

Latin translations of the main works of almost all the intellectually

crucial ancient authors,

allowing a sound transfer of scientific ideas via both the universities

and the monasteries. By then, the natural science contained in these

texts began to be extended by notable scholastics such as Robert Grosseteste, Roger Bacon, Albertus Magnus and Duns Scotus. Precursors of the modern scientific method

can be seen already in Grosseteste's emphasis on mathematics as a way

to understand nature, and in the empirical approach admired by Bacon,

particularly in his Opus Majus.

Technology

During the 12th and 13th century in Europe there was a radical change

in the rate of new inventions, innovations in the ways of managing

traditional means of production, and economic growth. In less than a

century there were more inventions developed and applied usefully than

in the previous thousand years of human history all over the globe. The

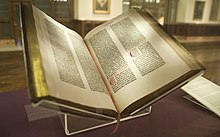

period saw major technological advances, including the adoption or invention of windmills, watermills, printing (though not yet with movable type), gunpowder, the astrolabe, glasses, scissors of the modern shape, a better clock, and greatly improved ships. The latter two advances made possible the dawn of the Age of Discovery. These inventions were influenced by foreign culture and society.

Alfred W. Crosby described some of this technological revolution in The Measure of Reality: Quantification in Western Europe, 1250-1600 and other major historians of technology have also noted it.

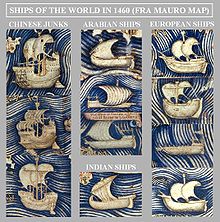

Ships of the world in 1460, according to the Fra Mauro map.

- The earliest written record of a windmill is from Yorkshire, England, dated 1185.

- Paper manufacture began in Italy around 1270.

- The spinning wheel was brought to Europe (probably from India) in the 13th century.

- The magnetic compass aided navigation, first reaching Europe some time in the late 12th century.

- Eye glasses were invented in Italy in the late 1280s.

- The astrolabe returned to Europe via Islamic Spain.

- Fibonacci introduces Arabic numerals to Europe with his book Liber Abaci in 1202.

- The West's oldest known depiction of a stern-mounted rudder can be found on church carvings dating to around 1180.

Arts

Visual arts

Fresco from the Boyana Church depicting Emperor Constantine Tikh Asen. The murals are among the finest achievements of the Bulgarian culture in the 13th century.

Art in the High Middle Ages includes these important movements:

- Anglo-Saxon art was influential on the British Isles until the Norman Invasion of 1066

- Romanesque art continued traditions from the Classical world (not to be confused with Romanesque architecture)

- Gothic art developed a distinct Germanic flavor (not to be confused with Gothic architecture).

- Byzantine art continued earlier Byzantine traditions, influencing much of Eastern Europe.

- Illuminated manuscripts gained prominence both in the Catholic and Orthodox churches

Architecture

Interior of Nôtre Dame de Paris

Gothic architecture superseded the Romanesque style by combining flying buttresses, gothic (or pointed) arches and ribbed vaults.

It was influenced by the spiritual background of the time, being

religious in essence: thin horizontal lines and grates made the building

strive towards the sky. Architecture was made to appear light and

weightless, as opposed to the dark and bulky forms of the previous Romanesque style. Saint Augustine of Hippo

taught that light was an expression of God. Architectural techniques

were adapted and developed to build churches that reflected this

teaching. Colorful glass windows

enhanced the spirit of lightness. As color was much rarer at medieval

times than today, it can be assumed that these virtuoso works of art had

an awe-inspiring impact on the common man from the street. High-rising

intricate ribbed, and later fan vaultings

demonstrated movement toward heaven. Veneration of God was also

expressed by the relatively large size of these buildings. A gothic

cathedral therefore not only invited the visitors to elevate themselves

spiritually, it was also meant to demonstrate the greatness of God. The floor plan of a gothic cathedral corresponded to the rules of scholasticism: According to Erwin Panofsky's Gothic Architecture and Scholasticism,

the plan was divided into sections and uniform subsections. These

characteristics are exhibited by the most famous sacral building of the

time: Notre Dame de Paris.

Literature

John the Apostle and Marcion of Sinope in an Italian illuminated manuscript, painting on vellum, 11th century

A variety of cultures influenced the literature of the High Middle

Ages, one of the strongest among them being Christianity. The connection

to Christianity was greatest in Latin literature, which influenced the vernacular languages in the literary cycle of the Matter of Rome. Other literary cycles, or interrelated groups of stories, included the Matter of France (stories about Charlemagne and his court), the Acritic songs dealing with the chivalry of Byzantium's frontiersmen, and perhaps the best known cycle, the Matter of Britain, which featured tales about King Arthur, his court, and related stories from Brittany, Cornwall, Wales and Ireland. An anonymous German poet tried to bring the Germanic myths from the Migration Period to the level of the French and British epics, producing the Nibelungenlied. There was also a quantity of poetry and historical writings which were written during this period, such as Historia Regum Britanniae by Geoffrey of Monmouth.

Despite political decline during the late 12th and much of the

13th centuries, the Byzantine scholarly tradition remained particularly

fruitful over the time period. One of the most prominent philosophers of

the 11th century, Michael Psellos, reinvigorated Neoplatonism on Christian foundations and bolstered the study of ancient philosophical texts, along with contributing to history, grammar, and rhetorics. His pupil and successor at the head of Philosophy at the University of Constantinople Ioannes Italos

continued the Platonic line in Byzantine thought and was criticized by

the Church for holding opinions it considered heretical, such as the

doctrine of transmigration. Two Orthodox theologians important in the dialogue between the eastern and western churches were Nikephoros Blemmydes and Maximus Planudes. Byzantine historical tradition also flourished with the works of the brothers Niketas and Michael Choniates in the beginning of the 13th century and George Akropolites a generation later. Dating from 12th century Byzantine Empire is also Timarion, an Orthodox Christian anticipation of Divine Comedy. Around the same time the so-called Byzantine novel rose in popularity with its synthesis of ancient pagan and contemporaneous Christian themes.

At the same time southern France gave birth to Occitan literature, which is best known for troubadours who sang of courtly love.

It included elements from Latin literature and Arab-influenced Spain

and North Africa. Later its influence spread to several cultures in

Western Europe, notably in Portugal and the Minnesänger in Germany.

Provençal literature also reached Sicily and Northern Italy laying the

foundation of the "sweet new style" of Dante and later Petrarca. Indeed, the most important poem of the Late Middle Ages, the allegorical Divine Comedy, is to a large degree a product of both the theology of Thomas Aquinas and the largely secular Occitan literature.

Music

Musicians playing the Spanish vihuela, one with a bow, the other plucked by hand, in the Cantigas de Santa Maria of Alfonso X of Castile, 13th century

Men playing the organistrum, from the Ourense Cathedral, Spain, 12th century

The surviving music of the High Middle Ages is primarily religious in nature, since music notation

developed in religious institutions, and the application of notation to

secular music was a later development. Early in the period, Gregorian chant was the dominant form of church music; other forms, beginning with organum, and later including clausulae, conductus, and the motet, developed using the chant as source material.

During the 11th century, Guido of Arezzo was one of the first to develop musical notation, which made it easier for singers to remember Gregorian chants.

It was during the 12th and 13th centuries that Gregorian

plainchant gave birth to polyphony, which appeared in the works of

French Notre Dame School (Léonin and Pérotin). Later it evolved into the ars nova (Philippe de Vitry, Guillaume de Machaut) and the musical genres of late Middle Ages. An important composer during the 12th century was the nun Hildegard of Bingen.

The most significant secular movement was that of the troubadours, who arose in Occitania (Southern France) in the late 11th century. The troubadours were often itinerant, came from all classes of society, and wrote songs on a variety of topics, though with a particular focus on courtly love. Their style went on to influence the trouvères of northern France, the minnesingers of Germany, and the composers of secular music of the Trecento in northern Italy.

Theater

Economic and political changes in the High Middle Ages led to the formation of guilds and the growth of towns, and this would lead to significant changes for theater starting in this time and continuing into the Late Middle Ages.

Trade guilds began to perform plays, usually religiously based, and

often dealing with a biblical story that referenced their profession.

For instance, a baker's guild would perform a reenactment of the Last Supper. In the British Isles, plays were produced in some 127 different towns during the Middle Ages. These vernacular Mystery plays were written in cycles of a large number of plays: York (48 plays), Chester (24), Wakefield (32) and Unknown

(42). A larger number of plays survive from France and Germany in this

period and some type of religious dramas were performed in nearly every

European country in the Late Middle Ages. Many of these plays contained comedy, devils, villains and clowns.

There were also a number of secular performances staged in the Middle Ages, the earliest of which is The Play of the Greenwood by Adam de la Halle in 1276. It contains satirical scenes and folk material such as faeries and other supernatural occurrences. Farces

also rose dramatically in popularity after the 13th century. The

majority of these plays come from France and Germany and are similar in

tone and form, emphasizing sex and bodily excretions.