From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

This variation may be caused by a change in emitted light or by

something partly blocking the light, so variable stars are classified as

either:

- Intrinsic variables, whose luminosity actually changes; for example, because the star periodically swells and shrinks.

- Extrinsic variables, whose apparent changes in brightness are due to

changes in the amount of their light that can reach Earth; for example,

because the star has an orbiting companion that sometimes eclipses it.

Many, possibly most, stars have at least some variation in luminosity: the energy output of our

Sun, for example, varies by about 0.1% over an 11-year

solar cycle.

Discovery

An

ancient Egyptian calendar of lucky and unlucky days composed some 3,200

years ago may be the oldest preserved historical document of the

discovery of a variable star,

the eclipsing binary

Algol.

Of the modern astronomers, the first variable star was identified in 1638 when

Johannes Holwarda noticed that

Omicron Ceti (later named Mira) pulsated in a cycle taking 11 months; the star had previously been described as a nova by

David Fabricius in 1596. This discovery, combined with

supernovae observed in 1572 and 1604, proved that the starry sky was not eternally invariable as

Aristotle

and other ancient philosophers had taught. In this way, the discovery

of variable stars contributed to the astronomical revolution of the

sixteenth and early seventeenth centuries.

The second variable star to be described was the eclipsing variable Algol, by

Geminiano Montanari in 1669;

John Goodricke gave the correct explanation of its variability in 1784.

Chi Cygni was identified in 1686 by

G. Kirch, then

R Hydrae in 1704 by

G. D. Maraldi. By 1786 ten variable stars were known. John Goodricke himself discovered

Delta Cephei and

Beta Lyrae.

Since 1850 the number of known variable stars has increased rapidly,

especially after 1890 when it became possible to identify variable stars

by means of photography.

The latest edition of the

General Catalogue of Variable Stars

(2008) lists more than 46,000 variable stars in the Milky Way, as well

as 10,000 in other galaxies, and over 10,000 'suspected' variables.

Detecting variability

The

most common kinds of variability involve changes in brightness, but

other types of variability also occur, in particular changes in the

spectrum. By combining

light curve data with observed spectral changes, astronomers are often able to explain why a particular star is variable.

Variable star observations

Variable stars are generally analysed using

photometry,

spectrophotometry and

spectroscopy. Measurements of their changes in brightness can be plotted to produce

light curves. For regular variables, the

period of variation and its

amplitude

can be very well established; for many variable stars, though, these

quantities may vary slowly over time, or even from one period to the

next. Peak brightnesses in the light curve are known as

maxima, while troughs are known as

minima.

Amateur astronomers can do useful scientific study of variable stars by visually comparing the star with other stars within the same

telescopic

field of view of which the magnitudes are known and constant. By

estimating the variable's magnitude and noting the time of observation a

visual lightcurve can be constructed. The

American Association of Variable Star Observers collects such observations from participants around the world and shares the data with the scientific community.

From the light curve the following data are derived:

- are the brightness variations periodical, semiperiodical, irregular, or unique?

- what is the period of the brightness fluctuations?

- what is the shape of the light curve (symmetrical or not,

angular or smoothly varying, does each cycle have only one or more than

one minima, etcetera)?

From the spectrum the following data are derived:

- what kind of star is it: what is its temperature, its luminosity class (dwarf star, giant star, supergiant, etc.)?

- is it a single star, or a binary? (the combined spectrum of a binary

star may show elements from the spectra of each of the member stars)

- does the spectrum change with time? (for example, the star may turn hotter and cooler periodically)

- changes in brightness may depend strongly on the part of the

spectrum that is observed (for example, large variations in visible

light but hardly any changes in the infrared)

- if the wavelengths of spectral lines are shifted this points to

movements (for example, a periodical swelling and shrinking of the star,

or its rotation, or an expanding gas shell) (Doppler effect)

- strong magnetic fields on the star betray themselves in the spectrum

- abnormal emission or absorption lines may be indication of a hot stellar atmosphere, or gas clouds surrounding the star.

In very few cases it is possible to make pictures of a stellar disk. These may show darker spots on its surface.

Interpretation of observations

Combining

light curves with spectral data often gives a clue as to the changes

that occur in a variable star. For example, evidence for a pulsating

star is found in its shifting spectrum because its surface periodically

moves toward and away from us, with the same frequency as its changing

brightness.

About two-thirds of all variable stars appear to be pulsating. In the 1930s astronomer

Arthur Stanley Eddington

showed that the mathematical equations that describe the interior of a

star may lead to instabilities that cause a star to pulsate. The most

common type of instability is related to oscillations in the degree of

ionization in outer, convective layers of the star.

Suppose the star is in the swelling phase. Its outer layers

expand, causing them to cool. Because of the decreasing temperature the

degree of ionization also decreases. This makes the gas more

transparent, and thus makes it easier for the star to radiate its

energy. This in turn will make the star start to contract. As the gas is

thereby compressed, it is heated and the degree of ionization again

increases. This makes the gas more opaque, and radiation temporarily

becomes captured in the gas. This heats the gas further, leading it to

expand once again. Thus a cycle of expansion and compression (swelling

and shrinking) is maintained.

The pulsation of cepheids is known to be driven by oscillations in the ionization of

helium (from He

++ to He

+ and back to He

++).

Nomenclature

In a given constellation, the first variable stars discovered were designated with letters R through Z, e.g.

R Andromedae. This system of

nomenclature was developed by

Friedrich W. Argelander, who gave the first previously unnamed variable in a constellation the letter R, the first letter not used by

Bayer. Letters RR through RZ, SS through SZ, up to ZZ are used for the next discoveries, e.g.

RR Lyrae.

Later discoveries used letters AA through AZ, BB through BZ, and up to

QQ through QZ (with J omitted). Once those 334 combinations are

exhausted, variables are numbered in order of discovery, starting with

the prefixed V335 onwards.

Classification

Variable stars may be either intrinsic or extrinsic.

- Intrinsic variable stars: stars where the variability is

being caused by changes in the physical properties of the stars

themselves. This category can be divided into three subgroups.

- Pulsating variables, stars whose radius alternately expands and

contracts as part of their natural evolutionary ageing processes.

- Eruptive variables, stars who experience eruptions on their surfaces like flares or mass ejections.

- Cataclysmic or explosive variables, stars that undergo a cataclysmic change in their properties like novae and supernovae.

- Extrinsic variable stars: stars where the variability is caused by external properties like rotation or eclipses. There are two main subgroups.

- Eclipsing binaries, double stars where, as seen from Earth's vantage point the stars occasionally eclipse one another as they orbit.

- Rotating variables, stars whose variability is caused by phenomena

related to their rotation. Examples are stars with extreme "sunspots"

which affect the apparent brightness or stars that have fast rotation

speeds causing them to become ellipsoidal in shape.

These subgroups themselves are further divided into specific types of

variable stars that are usually named after their prototype. For

example, dwarf novae are designated U Geminorum stars after the first recognized star in the class, U Geminorum.

Intrinsic variable stars

Pulsating variable stars

The pulsating stars swell and shrink, affecting their brightness and spectrum. Pulsations are generally split into:

radial, where the entire star expands and shrinks as a whole; and

non-radial, where one part of the star expand while another part shrinks.

Depending on the type of pulsation and its location within the star, there is a natural or

fundamental frequency which determines the period of the star. Stars may also pulsate in a

harmonic or

overtone

which is a higher frequency, corresponding to a shorter period.

Pulsating variable stars sometimes have a single well-defined period,

but often they pulsate simultaneously with multiple frequencies and

complex analysis is required to determine the separate

interfering periods. In some cases, the pulsations do not have a defined frequency, causing a random variation, referred to as

stochastic. The study of stellar interiors using their pulsations is known as

asteroseismology.

The expansion phase of a pulsation is caused by the blocking of

the internal energy flow by material with a high opacity, but this must

occur at a particular depth of the star to create visible pulsations. If

the expansion occurs below a convective zone then no variation will be

visible at the surface. If the expansion occurs too close to the surface

the restoring force will be too weak to create a pulsation. The

restoring force to create the contraction phase of a pulsation can be

pressure if the pulsation occurs in a non-degenerate layer deep inside a

star, and this is called an

acoustic or

pressure mode of pulsation, abbreviated to

p-mode. In other cases, the restoring force is

gravity and this is called a

g-mode. Pulsating variable stars typically pulsate in only one of these modes.

Cepheids and cepheid-like variables

This group consists of several kinds of pulsating stars, all found on the

instability strip, that swell and shrink very regularly caused by the star's own mass

resonance, generally by the

fundamental frequency. Generally the

Eddington valve

mechanism for pulsating variables is believed to account for

cepheid-like pulsations. Each of the subgroups on the instability strip

has a fixed relationship between period and absolute magnitude, as well

as a relation between period and mean density of the star. The

period-luminosity relationship was first established for Delta Cepheids

by

Henrietta Leavitt, and makes these high luminosity Cepheids very useful for determining distances to galaxies within the

Local Group and beyond.

Edwin Hubble used this method to prove that the so-called spiral nebulae are in fact distant galaxies.

Note that the Cepheids are named only for

Delta Cephei, while a completely separate class of variables is named after

Beta Cephei.

Classical Cepheid variables

Classical Cepheids (or Delta Cephei variables) are population I

(young, massive, and luminous) yellow supergiants which undergo

pulsations with very regular periods on the order of days to months. On

September 10, 1784,

Edward Pigott detected the variability of

Eta Aquilae, the first known representative of the class of Cepheid variables. However, the namesake for classical Cepheids is the star

Delta Cephei, discovered to be variable by

John Goodricke a few months later.

Type II Cepheids

Type II Cepheids (historically termed W Virginis stars) have

extremely regular light pulsations and a luminosity relation much like

the δ Cephei variables, so initially they were confused with the latter

category. Type II Cepheids stars belong to older

Population II stars, than do the type I Cepheids. The Type II have somewhat lower

metallicity,

much lower mass, somewhat lower luminosity, and a slightly offset

period verses luminosity relationship, so it is always important to know

which type of star is being observed.

RR Lyrae variables

These stars are somewhat similar to Cepheids, but are not as luminous

and have shorter periods. They are older than type I Cepheids,

belonging to

Population II, but of lower mass than type II Cepheids. Due to their common occurrence in

globular clusters, they are occasionally referred to as

cluster Cepheids.

They also have a well established period-luminosity relationship, and

so are also useful as distance indicators. These A-type stars vary by

about 0.2–2 magnitudes (20% to over 500% change in luminosity) over a

period of several hours to a day or more.

Delta Scuti variables

Delta Scuti (δ Sct) variables are similar to Cepheids but much fainter and with much shorter periods. They were once known as

Dwarf Cepheids.

They often show many superimposed periods, which combine to form an

extremely complex light curve. The typical δ Scuti star has an amplitude

of 0.003–0.9 magnitudes (0.3% to about 130% change in luminosity) and a

period of 0.01–0.2 days. Their

spectral type is usually between A0 and F5.

SX Phoenicis variables

These stars of spectral type A2 to F5, similar to δ Scuti variables,

are found mainly in globular clusters. They exhibit fluctuations in

their brightness in the order of 0.7 magnitude (about 100% change in

luminosity) or so every 1 to 2 hours.

Rapidly oscillating Ap variables

These stars of spectral type A or occasionally F0, a sub-class of δ

Scuti variables found on the main sequence. They have extremely rapid

variations with periods of a few minutes and amplitudes of a few

thousandths of a magnitude.

Long period variables

The long period variables are cool evolved stars that pulsate with periods in the range of weeks to several years.

Mira variables

Mira variables are AGB red giants. Over periods of many months they fade and brighten by between 2.5 and 11

magnitudes, a sixfold to 30 thousandfold change in luminosity.

Mira

itself, also known as Omicron Ceti (ο Cet), varies in brightness from

almost 2nd magnitude to as faint as 10th magnitude with a period of

roughly 332 days. The very large visual amplitudes are mainly due to the

shifting of energy output between visual and infra-red as the

temperature of the star changes. In a few cases, Mira variables show

dramatic period changes over a period of decades, thought to be related

to the thermal pulsing cycle of the most advanced AGB stars.

Semiregular variables

These are

red giants or

supergiants.

Semiregular variables may show a definite period on occasion, but more

often show less well-defined variations that can sometimes be resolved

into multiple periods. A well-known example of a semiregular variable is

Betelgeuse,

which varies from about magnitudes +0.2 to +1.2 (a factor 2.5 change in

luminosity). At least some of the semi-regular variables are very

closely related to Mira variables, possibly the only difference being

pulsating in a different harmonic.

Slow irregular variables

These are

red giants or

supergiants

with little or no detectable periodicity. Some are poorly studied

semiregular variables, often with multiple periods, but others may

simply be chaotic.

Long secondary period variables

Many variable red giants and supergiants show variations over several

hundred to several thousand days. The brightness may change by several

magnitudes although it is often much smaller, with the more rapid

primary variations are superimposed. The reasons for this type of

variation are not clearly understood, being variously ascribed to

pulsations, binarity, and stellar rotation.

Beta Cephei variables

Beta Cephei (β Cep) variables (sometimes called

Beta Canis Majoris variables, especially in Europe)

undergo short period pulsations in the order of 0.1–0.6 days with an

amplitude of 0.01–0.3 magnitudes (1% to 30% change in luminosity). They

are at their brightest during minimum contraction. Many stars of this

kind exhibits multiple pulsation periods.

Slowly pulsating B-type stars

Slowly pulsating B (SPB) stars are hot main-sequence stars slightly

less luminous than the Beta Cephei stars, with longer periods and larger

amplitudes.

Very rapidly pulsating hot (subdwarf B) stars

The prototype of this rare class is

V361 Hydrae, a 15th magnitude

subdwarf B star.

They pulsate with periods of a few minutes and may simultaneous pulsate

with multiple periods. They have amplitudes of a few hundredths of a

magnitude and are given the GCVS acronym RPHS. They are

p-mode pulsators.

PV Telescopii variables

Stars in this class are type Bp supergiants with a period of 0.1–1

day and an amplitude of 0.1 magnitude on average. Their spectra are

peculiar by having weak

hydrogen while on the other hand

carbon and

helium lines are extra strong, a type of

Extreme helium star.

RV Tauri variables

These are yellow supergiant stars (actually low mass post-AGB stars

at the most luminous stage of their lives) which have alternating deep

and shallow minima. This double-peaked variation typically has periods

of 30–100 days and amplitudes of 3–4 magnitudes. Superimposed on this

variation, there may be long-term variations over periods of several

years. Their spectra are of type F or G at maximum light and type K or M

at minimum brightness. They lie near the instability strip, cooler than

type I Cepheids more luminous than type II Cepheids. Their pulsations

are caused by the same basic mechanisms related to helium opacity, but

they are at a very different stage of their lives.

Alpha Cygni variables

Alpha Cygni (α Cyg) variables are nonradially pulsating supergiants of

spectral classes B

ep to A

epIa.

Their periods range from several days to several weeks, and their

amplitudes of variation are typically of the order of 0.1 magnitudes.

The light changes, which often seem irregular, are caused by the

superposition of many oscillations with close periods.

Deneb, in the constellation of

Cygnus is the prototype of this class.

Gamma Doradus variables

Gamma Doradus (γ Dor) variables are non-radially pulsating main-sequence stars of

spectral classes F to late A. Their periods are around one day and their amplitudes typically of the order of 0.1 magnitudes.

Pulsating white dwarfs

These non-radially pulsating stars have short periods of hundreds to

thousands of seconds with tiny fluctuations of 0.001 to 0.2 magnitudes.

Known types of pulsating white dwarf (or pre-white dwarf) include the DAV, or ZZ Ceti, stars, with hydrogen-dominated atmospheres and the spectral type DA; DBV, or V777 Her, stars, with helium-dominated atmospheres and the spectral type DB; and GW Vir stars, with atmospheres dominated by helium, carbon, and oxygen. GW Vir stars may be subdivided into DOV and PNNV stars.

Solar-like oscillations

The

Sun

oscillates with very low amplitude in a large number of modes having

periods around 5 minutes. The study of these oscillations is known as

helioseismology. Oscillations in the Sun are driven stochastically by

convection in its outer layers. The term

solar-like oscillations

is used to describe oscillations in other stars that are excited in the

same way and the study of these oscillations is one of the main areas

of active research in the field of

asteroseismology.

BLAP variables

A Blue Large-Amplitude Pulsator (BLAP) is a pulsating star

characterized by changes of 0.2 to 0.4 magnitudes with typical periods

of 20 to 40 minutes.

Eruptive variable stars

Eruptive

variable stars show irregular or semi-regular brightness variations

caused by material being lost from the star, or in some cases being

accreted to it. Despite the name these are not explosive events, those

are the cataclysmic variables.

Protostars

Protostars are young objects that have not yet completed the process

of contraction from a gas nebula to a veritable star. Most protostars

exhibit irregular brightness variations.

Herbig Ae/Be stars

Variability of more massive (2–8

solar mass)

Herbig Ae/Be stars is thought to be due to gas-dust clumps, orbiting in the circumstellar disks.

Orion variables

Orion variables are young, hot

pre–main-sequence stars

usually embedded in nebulosity. They have irregular periods with

amplitudes of several magnitudes. A well-known subtype of Orion

variables are the

T Tauri variables. Variability of

T Tauri stars is due to spots on the stellar surface and gas-dust clumps, orbiting in the circumstellar disks.

FU Orionis variables

These stars reside in reflection nebulae and show gradual increases

in their luminosity in the order of 6 magnitudes followed by a lengthy

phase of constant brightness. They then dim by 2 magnitudes (six times

dimmer) or so over a period of many years.

V1057 Cygni for

example dimmed by 2.5 magnitude (ten times dimmer) during an eleven-year

period. FU Orionis variables are of spectral type A through G and are

possibly an evolutionary phase in the life of

T Tauri stars.

Giants and supergiants

Large

stars lose their matter relatively easily. For this reason variability

due to eruptions and mass loss is fairly common among giants and

supergiants.

Luminous blue variables

Also known as the

S Doradus variables, the most luminous stars known belong to this class. Examples include the

hypergiants η Carinae and

P Cygni.

They have permanent high mass loss, but at intervals of years internal

pulsations cause the star to exceed its Eddington limit and the mass

loss increases hugely. Visual brightness increases although the overall

luminosity is largely unchanged. Giant eruptions observed in a few LBVs

do increase the luminosity, so much so that they have been tagged

supernova impostors, and may be a different type of event.

Yellow hypergiants

These massive evolved stars are unstable due to their high luminosity

and position above the instability strip, and they exhibit slow but

sometimes large photometric and spectroscopic changes due to high mass

loss and occasional larger eruptions, combined with secular variation on

an observable timescale. The best known example is

Rho Cassiopeiae.

R Coronae Borealis variables

While classed as eruptive variables, these stars do not undergo

periodic increases in brightness. Instead they spend most of their time

at maximum brightness, but at irregular intervals they suddenly fade by

1–9 magnitudes (2.5 to 4000 times dimmer) before recovering to their

initial brightness over months to years. Most are classified as yellow

supergiants by luminosity, although they are actually post-AGB stars,

but there are both red and blue giant R CrB stars.

R Coronae Borealis (R CrB) is the prototype star.

DY Persei variables are a subclass of R CrB variables that have a periodic variability in addition to their eruptions.

Wolf–Rayet variables

Wolf–Rayet stars are massive hot stars that sometimes show

variability, probably due to several different causes including binary

interactions and rotating gas clumps around the star. They exhibit broad

emission line spectra with

helium,

nitrogen,

carbon and

oxygen lines. Variations in some stars appear to be stochastic while others show multiple periods.

Gamma Cassiopeiae variables

Gamma Cassiopeiae

(γ Cas) variables are non-supergiant fast-rotating B class emission

line-type stars that fluctuate irregularly by up to 1.5 magnitudes

(fourfold change in luminosity) due to the ejection of matter at their

equatorial regions caused by the rapid rotational velocity.

Flare stars

In main-sequence stars major eruptive variability is exceptional. It is common only among the

flare stars, also known as the

UV Ceti

variables, very faint main-sequence stars which undergo regular flares.

They increase in brightness by up to two magnitudes (six times

brighter) in just a few seconds, and then fade back to normal brightness

in half an hour or less. Several nearby red dwarfs are flare stars,

including

Proxima Centauri and

Wolf 359.

RS Canum Venaticorum variables

These are close binary systems with highly active chromospheres,

including huge sunspots and flares, believed to be enhanced by the close

companion. Variability scales ranges from days, close to the orbital

period and sometimes also with eclipses, to years as sunspot activity

varies.

Cataclysmic or explosive variable stars

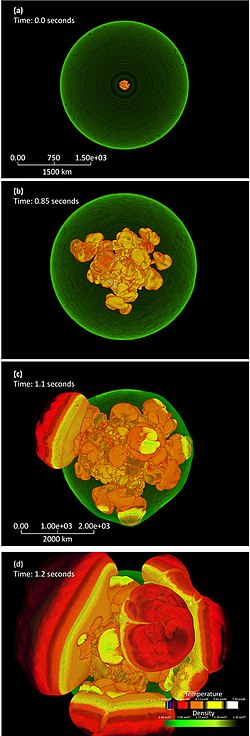

Images showing the expansion of the light echo of a red variable star, the V838 Monocerotis

Supernovae

Supernovae

are the most dramatic type of cataclysmic variable, being some of the

most energetic events in the universe. A supernova can briefly emit as

much energy as an entire

galaxy,

brightening by more than 20 magnitudes (over one hundred million times

brighter). The supernova explosion is caused by a white dwarf or a star

core reaching a certain mass/density limit, the

Chandrasekhar limit,

causing the object to collapse in a fraction of a second. This collapse

"bounces" and causes the star to explode and emit this enormous energy

quantity. The outer layers of these stars are blown away at speeds of

many thousands of kilometers an

hour. The expelled matter may form nebulae called

supernova remnants. A well-known example of such a nebula is the

Crab Nebula, left over from a supernova that was observed in

China and

North America in 1054. The core of the star or the white dwarf may either become a

neutron star (generally a

pulsar) or disintegrate completely in the explosion.

Supernovae can result from the death of an extremely massive

star, many times heavier than the Sun. At the end of the life of this

massive star, a non-fusible iron core is formed from fusion ashes. This

iron core is pushed towards the Chandrasekhar limit till it surpasses it

and therefore collapses.

A supernova may also result from mass transfer onto a

white dwarf

from a star companion in a double star system. The Chandrasekhar limit

is surpassed from the infalling matter. The absolute luminosity of this

latter type is related to properties of its light curve, so that these

supernovae can be used to establish the distance to other galaxies. One

of the most studied supernovae is

SN 1987A in the

Large Magellanic Cloud.

Novae

Novae

are also the result of dramatic explosions, but unlike supernovae do not

result in the destruction of the progenitor star. Also unlike

supernovae, novae ignite from the sudden onset of thermonuclear fusion,

which under certain high pressure conditions (

degenerate matter) accelerates explosively. They form in close

binary systems,

one component being a white dwarf accreting matter from the other

ordinary star component, and may recur over periods of decades to

centuries or millennia. Novae are categorised as

fast,

slow or

very slow, depending on the behaviour of their light curve. Several

naked eye novae have been recorded,

Nova Cygni 1975 being the brightest in the recent history, reaching 2nd magnitude.

Dwarf novae

Dwarf novae are double stars involving a

white dwarf in which matter transfer between the component gives rise to regular outbursts. There are three types of dwarf nova:

- U Geminorum stars,

which have outbursts lasting roughly 5–20 days followed by quiet

periods of typically a few hundred days. During an outburst they

brighten typically by 2–6 magnitudes. These stars are also known as SS Cygni variables after the variable in Cygnus which produces among the brightest and most frequent displays of this variable type.

- Z Camelopardalis stars, in which occasional plateaux of brightness called standstills are seen, part way between maximum and minimum brightness.

- SU Ursae Majoris stars, which undergo both frequent small outbursts, and rarer but larger superoutbursts. These binary systems usually have orbital periods of under 2.5 hours.

DQ Herculis variables

DQ Herculis systems are interacting binaries in which a low-mass star

transfers mass to a highly magnetic white dwarf. The white dwarf spin

period is significantly shorter than the binary orbital period and can

sometimes be detected as a photometric periodicity. An accretion disk

usually forms around the white dwarf, but its innermost regions are

magnetically truncated by the white dwarf. Once captured by the white

dwarf's magnetic field, the material from the inner disk travels along

the magnetic field lines until it accretes. In extreme cases, the white

dwarf's magnetism prevents the formation of an accretion disk.

AM Herculis variables

In these cataclysmic variables, the white dwarf's magnetic field is

so strong that it synchronizes the white dwarf's spin period with the

binary orbital period. Instead of forming an accretion disk, the

accretion flow is channeled along the white dwarf's magnetic field lines

until it impacts the white dwarf near a magnetic pole. Cyclotron

radiation beamed from the accretion region can cause orbital variations

of several magnitudes.

Z Andromedae variables

These symbiotic binary systems are composed of a red giant and a hot

blue star enveloped in a cloud of gas and dust. They undergo nova-like

outbursts with amplitudes of up to 4 magnitudes. The prototype for this

class is

Z Andromedae.

AM CVn variables

AM CVn variables are symbiotic binaries where a white dwarf is

accreting helium-rich material from either another white dwarf, a helium

star, or an evolved main-sequence star. They undergo complex

variations, or at times no variations, with ultrashort periods.

Extrinsic variable stars

There are two main groups of extrinsic variables: rotating stars and eclipsing stars.

Rotating variable stars

Stars with sizeable

sunspots

may show significant variations in brightness as they rotate, and

brighter areas of the surface are brought into view. Bright spots also

occur at the magnetic poles of magnetic stars. Stars with ellipsoidal

shapes may also show changes in brightness as they present varying areas

of their surfaces to the observer.

Non-spherical stars

Ellipsoidal variables

These

are very close binaries, the components of which are non-spherical due

to their mutual gravitation. As the stars rotate the area of their

surface presented towards the observer changes and this in turn affects

their brightness as seen from Earth.

Stellar spots

The surface of the star is not uniformly bright, but has darker and brighter areas (like the sun's

solar spots). The star's

chromosphere too may vary in brightness. As the star rotates we observe brightness variations of a few tenths of magnitudes.

FK Comae Berenices variables

BY Draconis stars are of spectral class K or M and vary by less than 0.5 magnitudes (70% change in luminosity).

Magnetic fields

Alpha-2 Canum Venaticorum variables

Alpha-2 Canum Venaticorum (α

2 CVn) variables are

main-sequence

stars of spectral class B8–A7 that show fluctuations of 0.01 to 0.1

magnitudes (1% to 10%) due to changes in their magnetic fields.

SX Arietis variables

Stars in this class exhibit brightness fluctuations of some 0.1

magnitude caused by changes in their magnetic fields due to high

rotation speeds.

Optically variable pulsars

Few

pulsars have been detected in

visible light. These

neutron stars

change in brightness as they rotate. Because of the rapid rotation,

brightness variations are extremely fast, from milliseconds to a few

seconds. The first and the best known example is the

Crab Pulsar.

Eclipsing binaries

How eclipsing binaries vary in brightness

Extrinsic variables have variations in their brightness, as seen by

terrestrial observers, due to some external source. One of the most

common reasons for this is the presence of a binary companion star, so

that the two together form a

binary star. When seen from certain angles, one star may

eclipse the other, causing a reduction in brightness. One of the most famous eclipsing binaries is

Algol, or Beta Persei (β Per).

Algol variables

Algol variables undergo eclipses with one or two minima separated by

periods of nearly constant light. The prototype of this class is

Algol in the

constellation Perseus.

Double Periodic variables

Double periodic variables exhibit cyclical mass exchange which causes

the orbital period to vary predictably over a very long period. The

best known example is

V393 Scorpii.

Beta Lyrae variables

Beta Lyrae (β Lyr) variables are extremely close binaries, named after the star

Sheliak.

The light curves of this class of eclipsing variables are constantly

changing, making it almost impossible to determine the exact onset and

end of each eclipse.

W Serpentis variables

W

Serpentis is the prototype of a class of semi-detached binaries

including a giant or supergiant transferring material to a massive more

compact star. They are characterised, and distinguished from the similar

β Lyr systems, by strong UV emission from accretions hotspots on a disc

of material.

W Ursae Majoris variables

The stars in this group show periods of less than a day. The stars

are so closely situated to each other that their surfaces are almost in

contact with each other.

Planetary transits

Stars with

planets

may also show brightness variations if their planets pass between Earth

and the star. These variations are much smaller than those seen with

stellar companions and are only detectable with extremely accurate

observations. Examples include

HD 209458 and

GSC 02652-01324, and all of the planets and planet candidates detected by the

Kepler Mission.