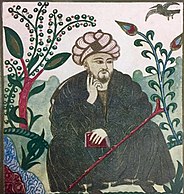

Title page of a 1550 edition

| |

| Author | Niccolò Machiavelli |

|---|---|

| Original title | De Principatibus / Il Principe |

| Country | Italy |

| Language | Italian |

| Subject | Political science |

| Genre | Non-fiction |

| Publisher | Antonio Blado d'Asola. |

Publication date

| 1532 |

| Followed by | Discourses on Livy |

The Prince (Italian: Il Principe [il ˈprintʃipe]) is a 16th-century political treatise by the Italian diplomat and political theorist Niccolò Machiavelli. From his correspondence, a version appears to have been distributed in 1513, using a Latin title, De Principatibus (Of Principalities). However, the printed version was not published until 1532, five years after Machiavelli's death. This was carried out with the permission of the Medici pope Clement VII, but "long before then, in fact since the first appearance of The Prince in manuscript, controversy had swirled about his writings".

Although The Prince was written as if it were a traditional work in the mirrors for princes style, it is generally agreed that it was especially innovative. This is partly because it was written in the vernacular Italian rather than Latin, a practice that had become increasingly popular since the publication of Dante's Divine Comedy and other works of Renaissance literature.

The Prince is sometimes claimed to be one of the first works of modern philosophy, especially modern political philosophy, in which the "effectual" truth is taken to be more important than any abstract ideal. It is also notable for being in direct conflict with the dominant Catholic and scholastic doctrines of the time, particularly those concerning politics and ethics.

Although it is relatively short, the treatise is the most remembered of Machiavelli's works and the one most responsible for bringing the word "Machiavellian" into usage as a pejorative. It even contributed to the modern negative connotations of the words "politics" and "politician" in western countries. In subject matter it overlaps with the much longer Discourses on Livy, which was written a few years later. In its use of near-contemporary Italians as examples of people who perpetrated criminal deeds for politics, another lesser-known work by Machiavelli which The Prince has been compared to is the Life of Castruccio Castracani.

The descriptions within The Prince have the general theme of accepting that the aims of princes – such as glory and survival – can justify the use of immoral means to achieve those ends:

He who neglects what is done for what ought to be done, sooner effects his ruin than his preservation.

Summary

Each part of The Prince

has been extensively commented on over centuries. The work has a

recognizable structure, for the most part indicated by the author

himself. It can be summarized as follows:

Letter to Magnificent Lorenzo de' Medici

Machiavelli prefaces his work with an introductory letter to Lorenzo de' Medici, Duke of Urbino, the recipient of his work.

The subject matter: New Princedoms (Chapters 1 and 2)

The Prince starts by describing the subject matter it will handle. In the first sentence, Machiavelli uses the word "state" (Italian stato which could also mean "status")

in order to cover, in neutral terms, "all forms of organization of

supreme political power, whether republican or princely." The way in

which the word state came to acquire this modern type of meaning during the Renaissance

has been the subject of much academic debate, with this sentence and

similar ones in the works of Machiavelli being considered particularly

important.

Machiavelli says that The Prince would be about princedoms, mentioning that he has written about republics elsewhere (a reference to the Discourses on Livy), but in fact he mixes discussion of republics into this work in many places, effectively treating republics as a type of princedom

also, and one with many strengths. More importantly, and less

traditionally, he distinguishes new princedoms from hereditary

established princedoms.

He deals with hereditary princedoms quickly in Chapter 2, saying that

they are much easier to rule. For such a prince, "unless extraordinary

vices cause him to be hated, it is reasonable to expect that his

subjects will be naturally well disposed towards him". Gilbert (1938:19–23),

comparing this claim to traditional presentations of advice for

princes, wrote that the novelty in chapters 1 and 2 is the "deliberate

purpose of dealing with a new ruler who will need to establish himself

in defiance of custom". Normally, these types of works were addressed

only to hereditary princes. He thinks Machiavelli may have been

influenced by Tacitus as well as his own experience, but finds no clear predecessor to substantiate this claim.

This categorization of regime types is also "un-Aristotelian" and apparently simpler than the traditional one found for example in Aristotle's Politics, which divides regimes into those ruled by a single monarch, an oligarchy, or by the people, in a democracy.

Machiavelli also ignores the classical distinctions between the good

and corrupt forms, for example between monarchy and tyranny.

Xenophon, on the other hand, made exactly the same distinction between types of rulers in the beginning of his Education of Cyrus where he says that, concerning the knowledge of how to rule human beings, Cyrus the Great,

his exemplary prince, was very different "from all other kings, both

those who have inherited their thrones from their fathers and those who

have gained their crowns by their own efforts".

Machiavelli divides the subject of new states into two types, "mixed" cases and purely new states.

"Mixed" princedoms (Chapters 3–5)

New

princedoms are either totally new, or they are "mixed", meaning that

they are new parts of an older state, already belonging to that prince.

New conquests added to older states (Chapter 3)

Machiavelli

generalizes that there were several virtuous Roman ways to hold a newly

acquired province, using a republic as an example of how new princes

can act:

- to install one's princedom in the new acquisition, or to install colonies of one's people there, which is better.

- to indulge the lesser powers of the area without increasing their power.

- to put down the powerful people.

- not to allow a foreign power to gain reputation.

More generally, Machiavelli emphasizes that one should have regard

not only for present problems but also for the future ones. One should

not "enjoy the benefit of time" but rather the benefit of one's virtue

and prudence, because time can bring evil as well as good.

Machiavelli notes in this chapter on the "natural and ordinary

desire to acquire" and as such, those who act on this desire can be

"praised or blamed" depending on the success of their acquisitions. He

then goes into detail about how the King of France failed in his

conquest of Italy, even saying how he could have succeeded. Machiavelli

views injuring enemies an necessity, stating that "if an injury is to be

done to a man, it should be so severe that the prince is not in fear of

revenge".

Conquered kingdoms (Chapter 4)

A 16th-century Italian impression of the family of Darius III, emperor of Persia, before their conqueror, Alexander the Great. Machiavelli explained that in his time the Near East was again ruled by an empire, the Ottoman Empire, with similar characteristics to that of Darius – seen from the viewpoint of a potential conqueror.

In some cases the old king of the conquered kingdom depended on his

lords. 16th century France, or in other words France as it was at the

time of writing of The Prince, is given by Machiavelli as an example of such a kingdom. These are easy to enter but difficult to hold.

When the kingdom revolves around the king, with everyone else his

servant, then it is difficult to enter but easy to hold. The solution

is to eliminate the old bloodline of the prince. Machiavelli used the Persian empire of Darius III, conquered by Alexander the Great,

to illustrate this point and then noted that the Medici, if they think

about it, will find this historical example similar to the "kingdom of

the Turk" (Ottoman Empire) in their time – making this a potentially easier conquest to hold than France would be.

Conquered Free States, with their own laws and orders (Chapter 5)

Gilbert (1938:34)

notes that this chapter is quite atypical of any previous books for

princes. Gilbert supposed the need to discuss conquering free republics

is linked to Machiavelli's project to unite Italy, which contained some

free republics. As he also notes, the chapter in any case makes it clear

that holding such a state is highly difficult for a prince. Machiavelli

gives three options:

- Ruin them, as Rome destroyed Carthage, and also as Machiavelli says the Romans eventually had to do in Greece.

- Go to live there (or install colonies, if you are a prince of a republic).

- Let them keep their own orders but install a puppet regime.

Machiavelli advises the ruler to go the first route, stating that if a

prince doesn't destroy a city, he can expect "to be destroyed by it".

Totally New States (Chapters 6–9)

Conquests by virtue (Chapter 6)

Machiavelli described Moses

as a conquering prince, who founded new modes and orders by force of

arms, which he used willingly to kill many of his own people. The Bible

describes the reasons behind his success differently.

Princes who rise to power through their own skill and resources

(their "virtue") rather than luck tend to have a hard time rising to the

top, but once they reach the top they are very secure in their

position. This is because they effectively crush their opponents and

earn great respect from everyone else. Because they are strong and more

self-sufficient, they have to make fewer compromises with their allies.

Machiavelli writes that reforming an existing order is one of the

most dangerous and difficult things a prince can do. Part of the reason

is that people are naturally resistant to change and reform. Those who

benefited from the old order will resist change very fiercely. By

contrast, those who can benefit from the new order will be less fierce

in their support, because the new order is unfamiliar and they are not

certain it will live up to its promises. Moreover, it is impossible for

the prince to satisfy everybody's expectations. Inevitably, he will

disappoint some of his followers. Therefore, a prince must have the

means to force his supporters to keep supporting him even when they

start having second thoughts, otherwise he will lose his power. Only

armed prophets, like Moses, succeed in bringing lasting change.

Machiavelli claims that Moses killed uncountable numbers of his own

people in order to enforce his will.

Machiavelli was not the first thinker to notice this pattern.

Allan Gilbert wrote: "In wishing new laws and yet seeing danger in them

Machiavelli was not himself an innovator," because this idea was traditional and could be found in Aristotle's

writings. But Machiavelli went much further than any other author in

his emphasis on this aim, and Gilbert associates Machiavelli's emphasis

upon such drastic aims with the level of corruption to be found in

Italy.

Conquest by fortune, meaning by someone else’s virtue (Chapter 7)

According

to Machiavelli, when a prince comes to power through luck or the

blessings of powerful figures within the regime, he typically has an

easy time gaining power but a hard time keeping it thereafter, because

his power is dependent on his benefactors' goodwill. He does not command

the loyalty of the armies and officials that maintain his authority,

and these can be withdrawn from him at a whim. Having risen the easy

way, it is not even certain such a prince has the skill and strength to

stand on his own feet.

This is not necessarily true in every case. Machiavelli cites Cesare Borgia

as an example of a lucky prince who escaped this pattern. Through

cunning political maneuvers, he managed to secure his power base.

Cesare was made commander of the papal armies by his father, Pope Alexander VI,

but was also heavily dependent on mercenary armies loyal to the Orsini

brothers and the support of the French king. Borgia won over the

allegiance of the Orsini brothers' followers with better pay and

prestigious government posts. To pacify the Romagna, he sent in his

henchman, Remirro de Orco, to commit acts of violence. When Remirro

started to become hated for his actions, Borgia responded by ordering

him to be "cut in two" to show the people that the cruelty was not from

him, although it was.

When some of his mercenary captains started to plot against him, he had

them captured and executed. When it looked as though the king of France

would abandon him, Borgia sought new alliances.

Finally, Machiavelli makes a point that bringing new benefits to a

conquered people will not be enough to cancel the memory of old

injuries, an idea Allan Gilbert said can be found in Tacitus and Seneca the Younger.

Of Those Who Have Obtained a Principality Through Crimes (Chapter 8)

Conquests

by "criminal virtue" are ones in which the new prince secures his power

through cruel, immoral deeds, such as the elimination of political

rivals.

Machiavelli's offers two rulers to imitate, Agathocles of Syracuse, and Oliverotto Euffreducci.

After Agathocles became Praetor of Syracuse, he called a meeting of

the city's elite. At his signal, his soldiers killed all the senators

and the wealthiest citizens, completely destroying the old oligarchy. He

declared himself ruler with no opposition. So secure was his power that

he could afford to absent himself to go off on military campaigns in

Africa.

Machiavelli then states that the behavior of Agathocles is not

simply virtue, as he says, "Yet one cannot call it virtue to kill one's

citizens, betray one's friends, to be without faith, without mercy,

without religion; these modes can enable one to acquire empire, but not

glory. [...] Nonetheless, his savage cruelty and inhumanity, together

with his infinite crimes, do not permit him to be celebrated among the

most excellent men. Thus, one cannot attribute to fortune or virtue

what he achieved without either."

Machiavelli then goes to his next example, Oliverotto de Fermo, an Italian condottiero

who recently came to power by killing all his enemies, including his

uncle Giovanni Fogliani, at a banquet. After he laid siege to the

governing council and terrified the citizenry, he had then set up a

government with himself as absolute ruler. However, in an ironic twist,

Oliverotto was killed the same way his opponents were, as Cesare Borgia

had him strangled after he invited Oliverotto and Vitellozzo Vitelli to a

friendly setting.

Machiavelli advises that a prince should carefully calculate all

the wicked deeds he needs to do to secure his power, and then execute

them all in one stroke. In this way, his subjects will slowly forget

his cruel deeds and the prince can better align himself with his

subjects. Princes who fail to do this, who hesitate in their

ruthlessness, will have to "keep a knife by his side" and protect

himself at all costs, as he can never trust himself amongst his

subjects.

Gilbert (1938:51–55)

remarks that this chapter is even less traditional than those it

follows, not only in its treatment of criminal behavior, but also in the

advice to take power from people at a stroke, noting that precisely the

opposite had been advised by Aristotle in his Politics

(5.11.1315a13). On the other hand, Gilbert shows that another piece of

advice in this chapter, to give benefits when it will not appear forced,

was traditional.

Becoming a prince by the selection of one's fellow citizens (Chapter 9)

A

"civil principality" is one in which a citizen comes to power "not

through crime or other intolerable violence", but by the support of his

fellow citizens. This, he says, does not require extreme virtue or

fortune, only "fortunate astuteness".

Machiavelli makes an important distinction between two groups

that are present in every city, and have very different appetites

driving them: the "great" and the "people". The "great" wish to oppress

and rule the "people", while the "people" wish not to be ruled or

oppressed. A principality is not the only outcome possible from these

appetites, because it can also lead to either "liberty" or "license".

A principality is put into place either by the "great" or the

"people" when they have the opportunity to take power, but find

resistance from the other side. They assign a leader who can be popular

to the people while the great benefit, or a strong authority defending

the people against the great.

Machiavelli goes on to say that a prince who obtains power through the

support of the nobles has a harder time staying in power than someone

who is chosen by the common people; since the former finds himself

surrounded by people who consider themselves his equals. He has to

resort to malevolent measures to satisfy the nobles.

One cannot by fair dealing, and without injury to others, satisfy the nobles, but you can satisfy the people, for their object is more righteous than that of the nobles, the latter wishing to oppress, while the former only desire not to be oppressed.

Also a prince cannot afford to keep the common people hostile as they are larger in number while the nobles smaller.

Therefore, the great should be made and unmade every day. There are two types of great people that might be encountered:

- Those who are bound to the prince. Concerning these it is important to distinguish between two types of obligated great people, those who are rapacious and those who are not. It is the latter who can and should be honoured.

- Those who are not bound to the new prince. Once again these need to be divided into two types: those with a weak spirit (a prince can make use of them if they are of good counsel) and those who shun being bound because of their own ambition (these should be watched and feared as enemies).

How to win over people depends on circumstances. Machiavelli advises:

- Do not get frightened in adversity.

- One should avoid ruling via magistrates, if one wishes to be able to "ascend" to absolute rule quickly and safely.

- One should make sure that the people need the prince, especially if a time of need should come.

How to judge the strength of principalities (Chapter 10)

The

way to judge the strength of a princedom is to see whether it can

defend itself, or whether it needs to depend on allies. This does not

just mean that the cities should be prepared and the people trained; a

prince who is hated is also exposed.

Ecclesiastical principates (Chapter 11)

Leo X: a pope, but also a member of the Medici family. Machiavelli suggested they should treat the church as a princedom, as the Borgia family had, in order to conquer Italy, and found new modes and orders.

This type of "princedom" refers for example explicitly to the

Catholic church, which is of course not traditionally thought of as a

princedom. According to Machiavelli, these are relatively easy to

maintain, once founded. They do not need to defend themselves

militarily, nor to govern their subjects.

Machiavelli discusses the recent history of the Church as if it

were a princedom that was in competition to conquer Italy against other

princes. He points to factionalism as a historical weak point in the

Church, and points to the recent example of the Borgia family as a better strategy which almost worked. He then explicitly proposes that the Medici are now in a position to try the same thing.

Defense and military (Chapter 12–14)

Having discussed the various types of principalities,

Machiavelli turns to the ways a state can attack other territories or

defend itself. The two most essential foundations for any state, whether

old or new, are sound laws and strong military forces.

A self-sufficient prince is one who can meet any enemy on the

battlefield. He should be "armed" with his own arms. However, a prince

that relies solely on fortifications or on the help of others and stands

on the defensive is not self-sufficient. If he cannot raise a

formidable army, but must rely on defense, he must fortify his city. A

well-fortified city is unlikely to be attacked, and if it is, most

armies cannot endure an extended siege. However, during a siege a

virtuous prince will keep the morale of his subjects high while removing

all dissenters. Thus, as long as the city is properly defended and has enough supplies, a wise prince can withstand any siege.

Machiavelli stands strongly against the use of mercenaries,

and in this he was innovative, and he also had personal experience in

Florence. He believes they are useless to a ruler because they are

undisciplined, cowardly, and without any loyalty, being motivated only

by money. Machiavelli attributes the Italian city states’ weakness to

their reliance on mercenary armies.

Machiavelli also warns against using auxiliary forces, troops

borrowed from an ally, because if they win, the employer is under their

favor and if they lose, he is ruined. Auxiliary forces are more

dangerous than mercenary forces because they are united and controlled

by capable leaders who may turn against the employer.

The main concern for a prince should be war, or the preparation

thereof, not books. Through war a hereditary prince maintains his power

or a private citizen rises to power. Machiavelli advises that a prince

must frequently hunt in order to keep his body fit and learn the

landscape surrounding his kingdom. Through this, he can best learn how

to protect his territory and advance upon others. For intellectual

strength, he is advised to study great military men so he may imitate

their successes and avoid their mistakes. A prince who is diligent in

times of peace will be ready in times of adversity. Machiavelli writes,

“thus, when fortune turns against him he will be prepared to resist it.”

The Qualities of a Prince (Chapters 14–19)

Each

of the following chapters presents a discussion about a particular

virtue or vice that a prince might have, and is therefore structured in a

way which appears like traditional advice for a prince. However, the

advice is far from traditional.

A Prince's Duty Concerning Military Matters (Chapter 14)

Machiavelli

believes that a prince's main focus should be on perfecting the art of

war. He believes that by taking this profession an aspiring prince will

be able to acquire a state, and will be able to maintain what he has

gained. He claims that "being disarmed makes you despised." He believes

that the only way to ensure loyalty from one's soldiers is to understand

military matters.

The two activities Machiavelli recommends practicing to prepare for war

are physical and mental. Physically, he believes rulers should learn the

landscape of their territories. Mentally, he encouraged the study of

past military events. He also warns against idleness.

Reputation of a prince (Chapter 15)

Because, says Machiavelli, he wants to write something useful to those

who understand, he thought it more fitting "to go directly to the

effectual truth ("verità effettuale") of the thing than to the

imagination of it". This section is one where Machiavelli's pragmatic

ideal can be seen most clearly. Machiavelli reasons that since princes

come across men who are evil, he should learn how to be equally evil

himself, and use this ability or not according to necessity. Concerning

the behavior of a prince toward his subjects, Machiavelli announces that

he will depart from what other writers say, and writes:

Men have imagined republics and principalities that never really existed at all. Yet the way men live is so far removed from the way they ought to live that anyone who abandons what is for what should be pursues his downfall rather than his preservation; for a man who strives after goodness in all his acts is sure to come to ruin, since there are so many men who are not good.

Since there are many possible qualities that a prince can be said to

possess, he must not be overly concerned about having all the good ones.

Also, a prince may be perceived to be merciful, faithful, humane,

frank, and religious, but most important is only to seem to have these qualities. A prince cannot truly have these qualities because at times it is necessary

to act against them. In fact, he must sometimes deliberately choose

evil. Although a bad reputation should be avoided, it is sometimes

necessary to have one.

Generosity vs. parsimony (Chapter 16)

If

a prince is overly generous to his subjects, Machiavelli asserts he

will not be appreciated, and will only cause greed for more.

Additionally, being overly generous is not economical, because

eventually all resources will be exhausted. This results in higher

taxes, and will bring grief upon the prince. Then, if he decides to

discontinue or limit his generosity, he will be labeled as a miser.

Thus, Machiavelli summarizes that guarding against the people's hatred

is more important than building up a reputation for generosity. A wise

prince should be willing to be more reputed a miser than be hated for

trying to be too generous.

On the other hand: "of what is not yours or your subjects' one can be a bigger giver, as were Cyrus, Caesar, and Alexander,

because spending what is someone else's does not take reputation from

you but adds it to you; only spending your own hurts you".

Cruelty vs. Mercy (Chapter 17)

Hannibal meeting Scipio Africanus. Machiavelli describes Hannibal as having the "virtue" of "inhuman cruelty". But he lost to someone, Scipio Africanus, who showed the weakness of "excessive mercy" and who could therefore only have held power in a republic.

Machiavelli begins this chapter by addressing how mercy can be

misused which will harm the prince and his dominion. He ends by stating

that a prince should not shrink from being cruel if it means that it

will keep his subjects in line. After all, it will help him maintain his

rule. He gives the example of Cesare Borgia, whose cruelty protected him from rebellions. He contrasts this example with the leaders of Florence, whom, through too much mercy, allowed disorders to plague their city.

In addressing the question of whether it is better to be loved or

feared, Machiavelli writes, "The answer is that one would like to be

both the one and the other; but because it is difficult to combine them,

it is far safer to be feared than loved if you cannot be both." As

Machiavelli asserts, commitments made in peace are not always kept in

adversity; however, commitments made in fear are kept out of fear. Yet, a

prince must ensure that he is not feared to the point of hatred, which

is very possible.

This chapter is possibly the most well-known of the work, and it

is important because of the reasoning behind Machiavelli's famous idea

that it is better to be feared than loved.

His justification is purely pragmatic; as he notes, "Men worry less

about doing an injury to one who makes himself loved than to one who

makes himself feared." Fear is used as a means to ensure obedience from

his subjects, and security for the prince. Above all, Machiavelli

argues, a prince should not interfere with the property of their

subjects or their women, and if they should try to kill someone, they

should do it with a convenient justification.

Regarding the troops of the prince, fear is absolutely necessary

to keep a large garrison united and a prince should not mind the thought

of cruelty in that regard. For a prince who leads his own army, it is

imperative for him to observe cruelty because that is the only way he

can command his soldiers' absolute respect. Machiavelli compares two

great military leaders: Hannibal and Scipio Africanus.

Although Hannibal's army consisted of men of various races, they were

never rebellious because they feared their leader. Machiavelli says this

required "inhuman cruelty" which he refers to as a virtue. Scipio's

men, on the other hand, were known for their mutiny and dissension, due

to Scipio's "excessive mercy" – which was, however, a source of glory

because he lived in a republic.

In what way princes should keep their word (Chapter 18)

Machiavelli

notes that a prince is praised for keeping his word. However, he also

notes that in reality, the most cunning princes succeed politically. A

prince, therefore, should only keep his word when it suits his purposes,

but do his utmost to maintain the illusion that he does keep his word

and that he is reliable in that regard. Machiavelli advises the ruler to

become a "great liar and deceiver", and that men are so easy to

deceive, that the ruler won't have an issue with lying to others. He

justifies this by saying that men are wicked, and never keep their

words, therefore the ruler doesn't have to keep his.

As Machiavelli notes, "He should appear to be compassionate,

faithful to his word, guileless, and devout. And indeed he should be so.

But his disposition should be such that, if he needs to be the

opposite, he knows how." As noted in chapter 15, the prince must appear

to be virtuous in order to hide his actions, and he should be able to be

otherwise when the time calls for it; that includes being able to lie,

though however much he lies he should always keep the appearance of

being truthful.

In this chapter, Machiavelli uses "beasts" as a metaphor for

unscrupulous behavior. He states that while lawful conduct is part of

the nature of men, a prince should learn how to use the nature of both

men and beasts wisely to ensure the stability of his regime. In this

chapter however, his focus is solely on the "beastly" natures.

In particular, he compares the use of force to the "lion", and the use

of deception to the "fox", and advises the prince to study them both. In

employing this metaphor, Machiavelli apparently references De Officiis by the Roman orator and statesman Cicero, and subverts its conclusion, arguing instead that dishonorable behavior is sometimes politically necessary.

Avoiding contempt and hatred (Chapter 19)

Machiavelli

divides the fears which monarchs should have into internal (domestic)

and external (foreign) fears. Internal fears exist inside his kingdom

and focus on his subjects, Machiavelli warns to be suspicious of

everyone when hostile attitudes emerge. Machiavelli observes that the

majority of men are content as long as they are not deprived of their

property and women, and only a minority of men are ambitious enough to

be a concern. A prince should command respect through his conduct,

because a prince who does not raise the contempt of the nobles and keeps

the people satisfied, Machiavelli assures, should have no fear of

conspirators working with external powers. Conspiracy is very difficult

and risky in such a situation.

Machiavelli apparently seems to go back on his rule that a prince

can evade hate, as he says that he will eventually be hated by someone,

so he should seek to avoid being hated by the commonfolk.

Roman emperors, on the other hand, had not only the majority and

ambitious minority, but also a cruel and greedy military, who created

extra problems because they demanded. While a prince should avoid being

hated, he will eventually be hated by someone, so he must at least avoid

the hatred of the most powerful, and for the Roman emperors this

included the military who demanded iniquity against the people out of

their own greed. He uses Septimius Severus

as a model for new rulers to emulate, as he "embodied both the fox and

the lion". Severus outwitted and killed his military rivals, and

although he oppressed the people, Machiavelli says that he kept the

common people "satisfied and stupified".

Machiavelli notes that in his time only the Turkish empire had

the problem of the Romans, because in other lands the people had become

more powerful than the military.

The Prudence of the Prince (Chapters 20–25)

Whether ruling conquests with fortresses works (Chapter 20)

Machiavelli

mentions that placing fortresses in conquered territories, although it

sometimes works, often fails. Using fortresses can be a good plan, but

Machiavelli says he shall "blame anyone who, trusting in fortresses,

thinks little of being hated by the people". He cited Caterina Sforza, who used a fortress to defend herself but was eventually betrayed by her people.

Gaining honours (Chapter 21)

A prince truly earns honour by completing great feats. King Ferdinand of Spain

is cited by Machiavelli as an example of a monarch who gained esteem by

showing his ability through great feats and who, in the name of

religion, conquered many territories and kept his subjects occupied so

that they had no chance to rebel.

Regarding two warring states, Machiavelli asserts it is always wiser to

choose a side, rather than to be neutral. Machiavelli then provides the

following reasons why:

- If your allies win, you benefit whether or not you have more power than they have.

- If you are more powerful, then your allies are under your command; if your allies are stronger, they will always feel a certain obligation to you for your help.

- If your side loses, you still have an ally in the loser.

Machiavelli also notes that it is wise for a prince not to ally with a

stronger force unless compelled to do so. In conclusion, the most

important virtue is having the wisdom to discern what ventures will come

with the most reward and then pursuing them courageously.

Nobles and staff (Chapter 22)

The

selection of good servants is reflected directly upon the prince's

intelligence, so if they are loyal, the prince is considered wise;

however, when they are otherwise, the prince is open to adverse

criticism. Machiavelli asserts that there are three types of

intelligence:

- The kind that understands things for itself – which is excellent to have.

- The kind that understands what others can understand – which is good to have.

- The kind that does not understand for itself, nor through others – which is useless to have.

If the prince does not have the first type of intelligence, he should

at the very least have the second type. For, as Machiavelli states, “A

prince needs to have the discernment to recognize the good or bad in

what another says or does even though he has no acumen himself".

Avoiding flatterers (Chapter 23)

This

chapter displays a low opinion of flatterers; Machiavelli notes that

"Men are so happily absorbed in their own affairs and indulge in such

self-deception that it is difficult for them not to fall victim to this

plague; and some efforts to protect oneself from flatterers involve the

risk of becoming despised." Flatterers were seen as a great danger to a

prince, because their flattery could cause him to avoid wise counsel in

favor of rash action, but avoiding all advice, flattery or otherwise,

was equally bad; a middle road had to be taken. A prudent prince should

have a select group of wise counselors to advise him truthfully on

matters all the time. All their opinions should be taken into account.

Ultimately, the decision should be made by the prince and carried out

absolutely. If a prince is given to changing his mind, his reputation

will suffer. A prince must have the wisdom to recognize good advice from

bad. Machiavelli gives a negative example in Emperor Maximilian I;

Maximilian, who was secretive, never consulted others, but once he

ordered his plans and met dissent, he immediately changed them.

Prudence and chance

Why the princes of Italy lost their states (Chapter 24)

After

first mentioning that a new prince can quickly become as respected as a

hereditary one, Machiavelli says princes in Italy who had longstanding

power and lost it cannot blame bad luck, but should blame their own

indolence. One "should never fall in the belief that you can find

someone to pick you up". They all showed a defect of arms (already

discussed) and either had a hostile populace or did not know to secure

themselves against the great.

How Much Fortune Can Do In Human Affairs, and in What Mode It May Be Opposed (Chapter 25)

As pointed out by Gilbert (1938:206)

it was traditional in the genre of Mirrors of Princes to mention

fortune, but "Fortune pervades The Prince as she does no other similar

work". Machiavelli argues that fortune is only the judge of half of our

actions and that we have control over the other half with "sweat",

prudence and virtue. Even more unusual, rather than simply suggesting

caution as a prudent way to try to avoid the worst of bad luck,

Machiavelli holds that the greatest princes in history tend to be ones

who take more risks, and rise to power through their own labour, virtue,

prudence, and particularly by their ability to adapt to changing

circumstances.

Machiavelli even encourages risk taking as a reaction to risk. In

a well-known metaphor, Machiavelli writes that "it is better to be

impetuous than cautious, because fortune is a woman; and it is

necessary, if one wants to hold her down, to beat her and strike her

down." Gilbert (p. 217) points out that Machiavelli's friend the historian and diplomat Francesco Guicciardini expressed similar ideas about fortune.

Machiavelli compares fortune to a torrential river that cannot be

easily controlled during flooding season. In periods of calm, however,

people can erect dams and levees in order to minimize its impact.

Fortune, Machiavelli argues, seems to strike at the places where no

resistance is offered, as had recently been the case in Italy. As de Alvarez (1999:125–30)

points out that what Machiavelli actually says is that Italians in his

time leave things not just to fortune, but to "fortune and God".

Machiavelli is indicating in this passage, as in some others in his

works, that Christianity itself was making Italians helpless and lazy

concerning their own politics, as if they would leave dangerous rivers

uncontrolled.

Exhortation to Seize Italy and to Free Her from the Barbarians (Chapter 26)

Pope Leo X

was pope at the time the book was written and a member of the de Medici

family. This chapter directly appeals to the Medici to use what has

been summarized in order to conquer Italy using Italian armies,

following the advice in the book. Gilbert (1938:222–30)

showed that including such exhortation was not unusual in the genre of

books full of advice for princes. But it is unusual that the Medici

family's position of Papal power is openly named as something that

should be used as a personal power base, as a tool of secular politics.

Indeed, one example is the Borgia family's "recent" and controversial

attempts to use church power in secular politics, often brutally

executed. This continues a controversial theme throughout the book.

Analysis

Cesare Borgia,

Duke of Valentinois. According to Machiavelli, a risk taker and example

of a prince who acquired by "fortune". Failed in the end because of one

mistake: he was naïve to trust a new Pope.

As shown by his letter of dedication, Machiavelli's work eventually came to be dedicated to Lorenzo di Piero de' Medici, grandson of "Lorenzo the Magnificent", and a member of the ruling Florentine Medici family, whose uncle Giovanni became Pope Leo X

in 1513. It is known from his personal correspondence that it was

written during 1513, the year after the Medici took control of Florence,

and a few months after Machiavelli's arrest, torture, and banishment by

the in-coming Medici regime. It was discussed for a long time with Francesco Vettori – a friend of Machiavelli – whom he wanted to pass it and commend it to the Medici. The book had originally been intended for Giuliano di Lorenzo de' Medici, young Lorenzo's uncle, who however died in 1516. It is not certain that the work was ever read by any of the Medici before it was printed.

Machiavelli describes the contents as being an un-embellished summary

of his knowledge about the nature of princes and "the actions of great

men", based not only on reading but also, unusually, on real experience.

The types of political behavior which are discussed with apparent approval by Machiavelli in The Prince were regarded as shocking by contemporaries, and its immorality is still a subject of serious discussion.

Although the work advises princes how to tyrannize, Machiavelli is

generally thought to have preferred some form of republican government.

Some commentators justify his acceptance of immoral and criminal

actions by leaders by arguing that he lived during a time of continuous

political conflict and instability in Italy, and that his influence has

increased the "pleasures, equality and freedom" of many people,

loosening the grip of medieval Catholicism's "classical teleology",

which "disregarded not only the needs of individuals and the wants of

the common man, but stifled innovation, enterprise, and enquiry into

cause and effect relationships that now allow us to control nature".

On the other hand, Strauss (1958:11)

notes that "even if we were forced to grant that Machiavelli was

essentially a patriot or a scientist, we would not be forced to deny

that he was a teacher of evil".

Furthermore, Machiavelli "was too thoughtful not to know what he was

doing and too generous not to admit it to his reasonable friends".

Machiavelli emphasized the need for looking at the "effectual

truth" (verita effetuale), as opposed to relying on "imagined republics

and principalities". He states the difference between honorable behavior

and criminal behavior by using the metaphor of animals, saying that

"there are two ways of contending, one in accordance with the laws, the

other by force; the first of which is proper to men, the second to

beast". In The Prince

he does not explain what he thinks the best ethical or political goals

are, except the control of one's own fortune, as opposed to waiting to

see what chance brings. Machiavelli took it for granted that would-be

leaders naturally aim at glory or honour. He associated these goals with a need for "virtue" and "prudence"

in a leader, and saw such virtues as essential to good politics. That

great men should develop and use their virtue and prudence was a

traditional theme of advice to Christian princes. And that more virtue meant less reliance on chance was a classically influenced "humanist commonplace" in Machiavelli's time, as Fischer (2000:75)

says, even if it was somewhat controversial. However, Machiavelli went

far beyond other authors in his time, who in his opinion left things to

fortune, and therefore to bad rulers, because of their Christian

beliefs. He used the words "virtue" and "prudence" to refer to

glory-seeking and spirited excellence of character, in strong contrast

to the traditional Christian uses of those terms, but more keeping with

the original pre-Christian Greek and Roman concepts from which they

derived. He encouraged ambition and risk taking. So in another break with tradition, he treated not only stability, but also radical innovation,

as possible aims of a prince in a political community. Managing major

reforms can show off a Prince's virtue and give him glory. He clearly

felt Italy needed major reform in his time, and this opinion of his time

is widely shared.

Machiavelli's descriptions encourage leaders to attempt to

control their fortune gloriously, to the extreme extent that some

situations may call for a fresh "founding" (or re-founding) of the

"modes and orders" that define a community, despite the danger and

necessary evil and lawlessness of such a project. Founding a wholly new

state, or even a new religion, using injustice and immorality has even

been called the chief theme of The Prince.

Machiavelli justifies this position by explaining how if "a prince did

not win love he may escape hate" by personifying injustice and

immorality; therefore, he will never loosen his grip since "fear is held

by the apprehension of punishment" and never diminishes as time goes

by.

For a political theorist to do this in public was one of Machiavelli's

clearest breaks not just with medieval scholasticism, but with the

classical tradition of political philosophy, especially the favorite philosopher of Catholicism at the time, Aristotle. This is one of Machiavelli's most lasting influences upon modernity.

Nevertheless, Machiavelli was heavily influenced by classical pre-Christian political philosophy. According to Strauss (1958:291) Machiavelli refers to Xenophon more than Plato, Aristotle, and Cicero put together. Xenophon wrote one of the classic mirrors of princes, the Education of Cyrus. Gilbert (1938:236)

wrote: "The Cyrus of Xenophon was a hero to many a literary man of the

sixteenth century, but for Machiavelli he lived". Xenophon also, as

Strauss pointed out, wrote a dialogue, Hiero

which showed a wise man dealing sympathetically with a tyrant, coming

close to what Machiavelli would do in uprooting the ideal of "the

imagined prince". Xenophon however, like Plato and Aristotle, was a

follower of Socrates, and his works show approval of a "teleological argument", while Machiavelli rejected such arguments. On this matter, Strauss (1958:222–23) gives evidence that Machiavelli may have seen himself as having learned something from Democritus, Epicurus and classical materialism, which was however not associated with political realism, or even any interest in politics.

On the topic of rhetoric

Machiavelli, in his introduction, stated that "I have not embellished

or crammed this book with rounded periods or big, impressive words, or

with any blandishment or superfluous decoration of the kind which many

are in the habit of using to describe or adorn what they have produced".

This has been interpreted as showing a distancing from traditional

rhetoric styles, but there are echoes of classical rhetoric in several

areas. In Chapter 18, for example, he uses a metaphor of a lion and a

fox, examples of cunning and force; according to Zerba (2004:217), "the Roman author from whom Machiavelli in all likelihood drew the simile of the lion and the fox" was Cicero. The Rhetorica ad Herennium,

a work which was believed during Machiavelli's time to have been

written by Cicero, was used widely to teach rhetoric, and it is likely

that Machiavelli was familiar with it. Unlike Cicero's more widely

accepted works however, according to Cox (1997:1122),

"Ad Herennium ... offers a model of an ethical system that not only

condones the practice of force and deception but appears to regard them

as habitual and indeed germane to political activity". This makes it an

ideal text for Machiavelli to have used.

Influence

To quote Bireley (1990:14):

...there were in circulation approximately fifteen editions of the Prince and nineteen of the Discourses and French translations of each before they were placed on the Index of Paul IV in 1559, a measure which nearly stopped publication in Catholic areas except in France. Three principal writers took the field against Machiavelli between the publication of his works and their condemnation in 1559 and again by the Tridentine Index in 1564. These were the English cardinal Reginald Pole and the Portuguese bishop Jerónimo Osório, both of whom lived for many years in Italy, and the Italian humanist and later bishop, Ambrogio Caterino Politi.

Emperor Charles V, or Charles I of Spain. A Catholic king in the first generation to read The Prince.

Henry VIII of England. A king who eventually split with the Catholic church, and supported some protestant ideas in the first generation to read The Prince.

Machiavelli's ideas on how to accrue honour and power as a leader had

a profound impact on political leaders throughout the modern west,

helped by the new technology of the printing press. Pole reported that

it was spoken of highly by his enemy Thomas Cromwell in England, and had influenced Henry VIII in his turn towards Protestantism, and in his tactics, for example during the Pilgrimage of Grace. A copy was also possessed by the Catholic king and emperor Charles V. In France, after an initially mixed reaction, Machiavelli came to be associated with Catherine de Medici and the St Bartholomew's Day Massacre. As Bireley (1990:17)

reports, in the 16th century, Catholic writers "associated Machiavelli

with the Protestants, whereas Protestant authors saw him as Italian and

Catholic". In fact, he was apparently influencing both Catholic and

Protestant kings.

One of the most important early works dedicated to criticism of Machiavelli, especially The Prince, was that of the Huguenot, Innocent Gentillet, Discourse against Machiavelli, commonly also referred to as Anti Machiavel, published in Geneva in 1576. He accused Machiavelli of being an atheist and accused politicians of his time by saying that they treated his works as the "Koran of the courtiers".[50]

Another theme of Gentillet was more in the spirit of Machiavelli

himself: he questioned the effectiveness of immoral strategies (just as

Machiavelli had himself done, despite also explaining how they could

sometimes work). This became the theme of much future political

discourse in Europe during the 17th century. This includes the Catholic Counter Reformation writers summarised by Bireley: Giovanni Botero, Justus Lipsius, Carlo Scribani, Adam Contzen, Pedro de Ribadeneira, and Diego Saavedra Fajardo.

These authors criticized Machiavelli, but also followed him in many

ways. They accepted the need for a prince to be concerned with

reputation, and even a need for cunning and deceit, but compared to

Machiavelli, and like later modernist writers, they emphasized economic progress much more than the riskier ventures of war. These authors tended to cite Tacitus as their source for realist political advice, rather than Machiavelli, and this pretense came to be known as "Tacitism".

Modern materialist

philosophy developed in the 16th, 17th and 18th century, starting in

the generations after Machiavelli. The importance of Machiavelli's

realism was noted by many important figures in this endeavor, for

example Jean Bodin, Francis Bacon, Harrington, John Milton, Spinoza, Rousseau, Hume, Edward Gibbon, and Adam Smith.

Although he was not always mentioned by name as an inspiration, due to

his controversy, he is also thought to have been an influence for other

major philosophers, such as Montaigne, Descartes, Hobbes, Locke and Montesquieu.

In literature:

- Machiavelli is featured as a character in the prologue of Christopher Marlowe's The Jew of Malta.

- In William Shakespeare's tragedy Othello, the antagonist Iago has been noted by some literary critics as being archetypal in adhering to Machiavelli's ideals by advancing himself through machination and duplicity with the consequence of causing the demise of both Othello and Desdemona.

Amongst later political leaders:

- The republicanism in seventeenth-century England which led to the English Civil War, the Glorious Revolution and subsequent development of the English Constitution was strongly influenced by Machiavelli's political thought.

- Most of the founding fathers of the American Revolution are known or often proposed to have been strongly influenced by Machiavelli's political works, including Benjamin Franklin, James Madison, Thomas Jefferson, Alexander Hamilton and John Adams.

- Under the guidance of Voltaire, Frederick the Great of Prussia criticised Machiavelli's conclusions in his "Anti-Machiavel", published in 1740.

- At different stages in his life, Napoleon I of France wrote extensive comments to The Prince. After his defeat at Waterloo, these comments were found in the emperor's coach and taken by the Prussian military.

- Italian dictator Benito Mussolini wrote a discourse on The Prince.

- Soviet leader Joseph Stalin read The Prince and annotated his own copy.

20th-century Italian-American mobsters were influenced by The Prince. John Gotti and Roy DeMeo would regularly quote The Prince and consider it to be the

"Mafia Bible".

Interpretation of The Prince as political satire or as deceit

Satire

This interpretation was put forth by Ian Johnston (1958)

who argued that "the book is, first and foremost, a satire, so that

many of the things we find in it which are morally absurd, specious, and

contradictory, are there quite deliberately in order to ridicule ...

the very notion of tyrannical rule". Hence, Johnston says, "the satire

has a firm moral purpose – to expose tyranny and promote republican

government."

This position was taken up by some of the more prominent Enlightenment philosophes. Diderot speculated that it was a work designed to expose corrupt princely rule. And in his The Social Contract, the French philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau said:

Machiavelli was a proper man and a good citizen; but, being attached to the court of the Medici, he could not help veiling his love of liberty in the midst of his country's oppression. The choice of his detestable hero, Cesare Borgia, clearly enough shows his hidden aim; and the contradiction between the teaching of the Prince and that of the Discourses on Livy and the History of Florence shows that this profound political thinker has so far been studied only by superficial or corrupt readers. The Court of Rome sternly prohibited his book. I can well believe it; for it is that Court it most clearly portrays.

Whether or not the word "satire" is the best choice, a few

commentators still assert that despite seeming to be written for someone

wanting to be a monarch, and not the leader of a republic, The Prince can be read as deliberately emphasizing the benefits of free republics over monarchies.

Commentators differ about whether this sub-text was intended to

be understood, let alone understood as deliberately satirical or comic.

Deceit

One such

commentator, Mary Dietz, writes that Machiavelli's agenda was not to be

satirical, as Rousseau had argued, but instead was "offering carefully

crafted advice (such as arming the people) designed to undo the ruler if

taken seriously and followed."

By this account, the aim was to reestablish the republic in Florence.

She focuses on three categories in which Machiavelli gives paradoxical

advice:

- He discourages liberality and favors deceit to guarantee support from the people. Yet Machiavelli is keenly aware of the fact that an earlier pro-republican coup had been thwarted by the people's inaction that itself stemmed from the prince's liberality.

- He supports arming the people despite the fact that he knows the Florentines are decidedly pro-democratic and would oppose the prince.

- He encourages the prince to live in the city he conquers. This opposes the Medici's habitual policy of living outside the city. It also makes it easier for rebels or a civilian militia to attack and overthrow the prince.

According to Dietz the trap never succeeded because Lorenzo – "a

suspicious prince" – apparently never read the work of the "former

republican."

Other interpretations

The Italian Marxist philosopher Antonio Gramsci

argued that Machiavelli's audience for this work was not the classes

who already rule (or have "hegemony") over the common people, but the

common people themselves, trying to establish a new hegemony, and making

Machiavelli the first "Italian Jacobin".

Hans Baron is one of the few major commentators who argues that

Machiavelli must have changed his mind dramatically in favour of free

republics, after having written The Prince.