| Macrophage | |

|---|---|

A macrophage stretching its "arms" (filopodia) to engulf two particles, possibly pathogens, in a mouse. Trypan blue exclusion staining.

| |

| Details | |

| Pronunciation | /ˈmakrə(ʊ)feɪdʒ/ |

| System | Immune system |

| Function | Phagocytosis |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Macrophagocytus |

| Acronym(s) | Mφ, MΦ |

| MeSH | D008264 |

| TH | H2.00.03.0.01007 |

| FMA | 63261 |

Macrophages (abbreviated as Mφ, MΦ or MP) (Greek: large eaters, from Greek μακρός (makrós) = large, φαγεῖν (phagein) = to eat) are a type of white blood cell of the immune system that engulfs and digests cellular debris, foreign substances, microbes, cancer cells, and anything else that does not have the type of proteins specific to healthy body cells on its surface in a process called phagocytosis.

These large phagocytes are found in essentially all tissues, where they patrol for potential pathogens by amoeboid movement. They take various forms (with various names) throughout the body (e.g., histiocytes, Kupffer cells, alveolar macrophages, microglia, and others), but all are part of the mononuclear phagocyte system. Besides phagocytosis, they play a critical role in nonspecific defense (innate immunity) and also help initiate specific defense mechanisms (adaptive immunity) by recruiting other immune cells such as lymphocytes. For example, they are important as antigen presenters to T cells. In humans, dysfunctional macrophages cause severe diseases such as chronic granulomatous disease that result in frequent infections.

Beyond increasing inflammation and stimulating the immune system, macrophages also play an important anti-inflammatory role and can decrease immune reactions through the release of cytokines. Macrophages that encourage inflammation are called M1 macrophages, whereas those that decrease inflammation and encourage tissue repair are called M2 macrophages. This difference is reflected in their metabolism; M1 macrophages have the unique ability to metabolize arginine to the "killer" molecule nitric oxide, whereas rodent M2 macrophages have the unique ability to metabolize arginine to the "repair" molecule ornithine. However, this dichotomy has been recently questioned as further complexity has been discovered.

Human macrophages are about 21 micrometres (0.00083 in) in diameter and are produced by the differentiation of monocytes in tissues. They can be identified using flow cytometry or immunohistochemical staining by their specific expression of proteins such as CD14, CD40, CD11b, CD64, F4/80 (mice)/EMR1 (human), lysozyme M, MAC-1/MAC-3 and CD68.

Macrophages were first discovered by Élie Metchnikoff, a Russian zoologist, in 1884.

Structure

Types

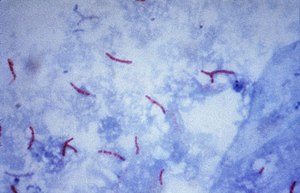

Drawing of a macrophage when fixed and stained by giemsa dye

A majority of macrophages are stationed at strategic points where

microbial invasion or accumulation of foreign particles is likely to

occur. These cells together as a group are known as the mononuclear phagocyte system

and were previously known as the reticuloendothelial system. Each type

of macrophage, determined by its location, has a specific name:

| Cell Name | Anatomical Location |

| Adipose tissue macrophages | Adipose tissue (fat) |

| Monocytes | Bone marrow / blood |

| Kupffer cells | Liver |

| Sinus histiocytes | Lymph nodes |

| Alveolar macrophages (dust cells) | Pulmonary alveoli |

| Tissue macrophages (histiocytes) leading to giant cells | Connective tissue |

| Microglia | Central nervous system |

| Hofbauer cells | Placenta |

| Intraglomerular mesangial cells | Kidney |

| Osteoclasts | Bone |

| Epithelioid cells | Granulomas |

| Red pulp macrophages (sinusoidal lining cells) | Red pulp of spleen |

| Peritoneal macrophages | Peritoneal cavity |

| LysoMac | Peyer's patch |

Investigations concerning Kupffer cells are hampered because in

humans, Kupffer cells are only accessible for immunohistochemical

analysis from biopsies or autopsies. From rats and mice, they are

difficult to isolate, and after purification, only approximately

5 million cells can be obtained from one mouse.

Macrophages can express paracrine functions within organs that are specific to the function of that organ. In the testis, for example, macrophages have been shown to be able to interact with Leydig cells by secreting 25-hydroxycholesterol, an oxysterol that can be converted to testosterone by neighbouring Leydig cells.

Also, testicular macrophages may participate in creating an immune

privileged environment in the testis, and in mediating infertility

during inflammation of the testis.

Cardiac resident macrophages participate in electrical conduction via gap junction communication with cardiac myocytes.

Macrophages can be classified on basis of the fundamental function and activation. According to this grouping there are classically-activated (M1) macrophages, wound-healing macrophages (also known as alternatively-activated (M2) macrophages), and regulatory macrophages (Mregs).

Development

Macrophages

that reside in adult healthy tissues either derive from circulating

monocytes or are established before birth and then maintained during

adult life independently of monocytes. By contrast, most of the macrophages that accumulate at diseased sites typically derive from circulating monocytes. When a monocyte enters damaged tissue through the endothelium of a blood vessel, a process known as leukocyte extravasation,

it undergoes a series of changes to become a macrophage. Monocytes are

attracted to a damaged site by chemical substances through chemotaxis, triggered by a range of stimuli including damaged cells, pathogens and cytokines

released by macrophages already at the site. At some sites such as the

testis, macrophages have been shown to populate the organ through

proliferation. Unlike short-lived neutrophils, macrophages survive longer in the body, up to several months.

Function

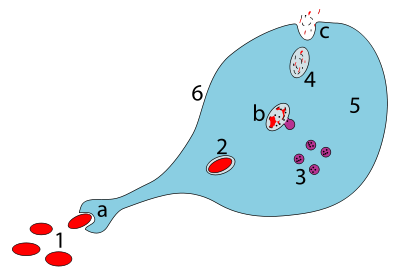

Steps of a macrophage ingesting a pathogen:

a. Ingestion through phagocytosis, a phagosome is formed

b. The fusion of lysosomes with the phagosome creates a phagolysosome; the pathogen is broken down by enzymes

c. Waste material is expelled or assimilated (the latter not pictured)

Parts:

1. Pathogens

2. Phagosome

3. Lysosomes

4. Waste material

5. Cytoplasm

6. Cell membrane

a. Ingestion through phagocytosis, a phagosome is formed

b. The fusion of lysosomes with the phagosome creates a phagolysosome; the pathogen is broken down by enzymes

c. Waste material is expelled or assimilated (the latter not pictured)

Parts:

1. Pathogens

2. Phagosome

3. Lysosomes

4. Waste material

5. Cytoplasm

6. Cell membrane

Phagocytosis

Macrophages are professional phagocytes

and are highly specialized in removal of dying or dead cells and

cellular debris. This role is important in chronic inflammation, as the

early stages of inflammation are dominated by neutrophils, which are

ingested by macrophages if they come of age (see CD31 for a description of this process).

The neutrophils are at first attracted to a site, where they

perform their function and die, before they are phagocytized by the

macrophages.

When at the site, the first wave of neutrophils, after the process of

aging and after the first 48 hours, stimulate the appearance of the

macrophages whereby these macrophages will then ingest the aged

neutrophils.

The removal of dying cells is, to a greater extent, handled by fixed macrophages,

which will stay at strategic locations such as the lungs, liver, neural

tissue, bone, spleen and connective tissue, ingesting foreign materials

such as pathogens and recruiting additional macrophages if needed.

When a macrophage ingests a pathogen, the pathogen becomes trapped in a phagosome, which then fuses with a lysosome. Within the phagolysosome, enzymes and toxic peroxides digest the pathogen. However, some bacteria, such as Mycobacterium tuberculosis, have become resistant to these methods of digestion. Typhoidal Salmonellae

induce their own phagocytosis by host macrophages in vivo, and inhibit

digestion by lysosomal action, thereby using macrophages for their own

replication and causing macrophage apoptosis. Macrophages can digest more than 100 bacteria before they finally die due to their own digestive compounds.

Role in adaptive immunity

Macrophages are versatile cells that play many roles. As scavengers, they rid the body of worn-out cells and other debris. Along with dendritic cells, they are foremost among the cells that present antigens,

a crucial role in initiating an immune response. As secretory cells,

monocytes and macrophages are vital to the regulation of immune

responses and the development of inflammation; they produce a wide array

of powerful chemical substances (monokines) including enzymes, complement proteins, and regulatory factors such as interleukin-1. At the same time, they carry receptors for lymphokines that allow them to be "activated" into single-minded pursuit of microbes and tumour cells.

After digesting a pathogen, a macrophage will present the antigen

(a molecule, most often a protein found on the surface of the pathogen

and used by the immune system for identification) of the pathogen to the

corresponding helper T cell. The presentation is done by integrating it into the cell membrane and displaying it attached to an MHC

class II molecule (MHCII), indicating to other white blood cells that

the macrophage is not a pathogen, despite having antigens on its

surface.

Eventually, the antigen presentation results in the production of antibodies

that attach to the antigens of pathogens, making them easier for

macrophages to adhere to with their cell membrane and phagocytose. In

some cases, pathogens are very resistant to adhesion by the macrophages.

The antigen presentation on the surface of infected macrophages (in the context of MHC class II) in a lymph node stimulates TH1 (type 1 helper T cells) to proliferate (mainly due to IL-12

secretion from the macrophage). When a B-cell in the lymph node

recognizes the same unprocessed surface antigen on the bacterium with

its surface bound antibody, the antigen is endocytosed and processed.

The processed antigen is then presented in MHCII on the surface of the

B-cell. T cells that express the T cell receptor which recognizes the

antigen-MHCII complex (with co-stimulatory factors- CD40 and CD40L) cause the B-cell to produce antibodies that help opsonisation of the antigen so that the bacteria can be better cleared by phagocytes.

Macrophages provide yet another line of defense against tumor cells and somatic cells infected with fungus or parasites.

Once a T cell has recognized its particular antigen on the surface of

an aberrant cell, the T cell becomes an activated effector cell,

producing chemical mediators known as lymphokines that stimulate

macrophages into a more aggressive form.

Macrophage subtypes

There are several activated forms of macrophages.

In spite of a spectrum of ways to activate macrophages, there are two

main groups designated M1 and M2. M1 macrophages: as mentioned earlier

(previously referred to as classically activated macrophages), M1 "killer" macrophages are activated by LPS and IFN-gamma, and secrete high levels of IL-12 and low levels of IL-10. M1 macrophages have pro-inflammatory, bactericidal, and phagocytic functions.

In contrast, the M2 "repair" designation (also referred to as

alternatively activated macrophages) broadly refers to macrophages that

function in constructive processes like wound healing and tissue repair,

and those that turn off damaging immune system activation by producing

anti-inflammatory cytokines like IL-10. M2 is the phenotype of resident tissue macrophages, and can be further elevated by IL-4. M2 macrophages produce high levels of IL-10, TGF-beta

and low levels of IL-12. Tumor-associated macrophages are mainly of the

M2 phenotype, and seem to actively promote tumor growth.

Macrophages exist in a variety of phenotypes which are determined

by the role they play in wound maturation. Phenotypes can be

predominantly separated into two major categories; M1 and M2. M1

macrophages are the dominating phenotype observed in the early stages of

inflammation and are activated by four key mediators: interferon-γ

(IFN-γ), tumor necrosis factor (TNF), and damage associated molecular

patterns (DAMPs). These mediator molecules create a pro-inflammatory

response that in return produce pro-inflammatory cytokines like

Interleukin-6 and TNF. Unlike M1 macrophages, M2 macrophages secrete an

anti-inflammatory response via the addition of Interleukin-4 or

Interleukin-13. They also play a role in wound healing and are needed

for revascularization and reepithelialization. M2 macrophages are

divided into four major types based on their roles: M2a, M2b, M2c, and

M2d. How M2 phenotypes are determined is still up for discussion but

studies have shown that their environment allows them to adjust to

whichever phenotype is most appropriate to efficiently heal the wound.

M2 macrophages are needed for vascular stability. They produce vascular epithelial growth factor-A and TGF-β1.

There is a phenotype shift from M1 to M2 macrophages in acute wounds,

however this shift is impaired for chronic wounds. This dysregulation

results in insufficient M2 macrophages and its corresponding growth

factors that aid in wound repair. With a lack of these growth

factors/anti-inflammatory cytokines and an overabundance of

pro-inflammatory cytokines from M1 macrophages chronic wounds are unable

to heal in a timely manner. Normally, after neutrophils eat

debris/pathogens they perform apoptosis and are removed. At this point,

inflammation is not needed and M1 undergoes a switch to M2

(anti-inflammatory). However, dysregulation occurs as the M1 macrophages

are unable/do not phagocytose neutrophils that have undergone apoptosis

leading to increased macrophage migration and inflammation.

Both M1 and M2 macrophages play a role in promotion of atherosclerosis.

M1 macrophages promote atherosclerosis by inflammation. M2 macrophages

can remove cholesterol from blood vessels, but when the cholesterol is

oxidized, the M2 macrophages become apoptotic foam cells contributing to the atheromatous plaque of atherosclerosis.

Role in muscle regeneration

The

first step to understanding the importance of macrophages in muscle

repair, growth, and regeneration is that there are two "waves" of

macrophages with the onset of damageable muscle use – subpopulations

that do and do not directly have an influence on repairing muscle. The

initial wave is a phagocytic population that comes along during periods

of increased muscle use that are sufficient to cause muscle membrane

lysis and membrane inflammation, which can enter and degrade the

contents of injured muscle fibers.

These early-invading, phagocytic macrophages reach their highest

concentration about 24 hours following the onset of some form of muscle

cell injury or reloading. Their concentration rapidly declines after 48 hours.

The second group is the non-phagocytic types that are distributed near

regenerative fibers. These peak between two and four days and remain

elevated for several days during the hopeful muscle rebuilding. The first subpopulation has no direct benefit to repairing muscle, while the second non-phagocytic group does.

It is thought that macrophages release soluble substances that

influence the proliferation, differentiation, growth, repair, and

regeneration of muscle, but at this time the factor that is produced to

mediate these effects is unknown.

It is known that macrophages' involvement in promoting tissue repair is

not muscle specific; they accumulate in numerous tissues during the

healing process phase following injury.

Role in wound healing

Macrophages are essential for wound healing. They replace polymorphonuclear neutrophils as the predominant cells in the wound by day two after injury. Attracted to the wound site by growth factors released by platelets and other cells, monocytes from the bloodstream enter the area through blood vessel walls.

Numbers of monocytes in the wound peak one to one and a half days after

the injury occurs. Once they are in the wound site, monocytes mature

into macrophages. The spleen contains half the body's monocytes in reserve ready to be deployed to injured tissue.

The macrophage's main role is to phagocytize bacteria and damaged tissue, and they also debride damaged tissue by releasing proteases.

Macrophages also secrete a number of factors such as growth factors and

other cytokines, especially during the third and fourth post-wound

days. These factors attract cells involved in the proliferation stage of

healing to the area. Macrophages may also restrain the contraction phase. Macrophages are stimulated by the low oxygen content of their surroundings to produce factors that induce and speed angiogenesis and they also stimulate cells that re-epithelialize the wound, create granulation tissue, and lay down a new extracellular matrix. By secreting these factors, macrophages contribute to pushing the wound healing process into the next phase.

Role in limb regeneration

Scientists have elucidated that as well as eating up material debris, macrophages are involved in the typical limb regeneration in the salamander. They found that removing the macrophages from a salamander resulted in failure of limb regeneration and a scarring response.

Role in iron homeostasis

As described above, macrophages play a key role in removing dying or dead cells and cellular debris. Erythrocytes

have a lifespan on average of 120 days and so are constantly being

destroyed by macrophages in the spleen and liver. Macrophages will also

engulf macromolecules, and so play a key role in the pharmacokinetics of parenteral irons.

The iron that is released from the haemoglobin is either stored internally in ferritin or is released into the circulation via ferroportin. In cases where systemic iron levels are raised, or where inflammation is present, raised levels of hepcidin act on macrophage ferroportin channels, leading to iron remaining within the macrophages.

Role in pigment retainment

Melanophage

Melanophages are a subset of

tissue-resident macrophages able to absorb pigment, either native to the

organism or exogenous (such as tattoos), from extracellular space. In contrast to dendritic juncional melanocytes, which synthesize melanosomes and contain various stages of their development, the melanophages only accumulate phagocytosed melanin in lysosome-like phagosomes.

This occurs repeatedly as the pigment from dead dermal macrophages is

phagocytosed by their successors, preserving the tattoo in the same

place.

Role in tissue homeostasis

Every

tissue harbors its own specialized population of resident macrophages,

which entertain reciprocal interconnections with the stroma and

functional tissue.

These resident macrophages are sessile (non-migratory), provide

essential growth factors to support the physiological function of the

tissue (e.g. macrophage-neuronal crosstalk in the guts), and can actively protect the tissue from inflammatory damage.

Clinical significance

Due

to their role in phagocytosis, macrophages are involved in many

diseases of the immune system. For example, they participate in the

formation of granulomas,

inflammatory lesions that may be caused by a large number of diseases.

Some disorders, mostly rare, of ineffective phagocytosis and macrophage

function have been described, for example.

As a host for intracellular pathogens

In

their role as a phagocytic immune cell macrophages are responsible for

engulfing pathogens to destroy them. Some pathogens subvert this process

and instead live inside the macrophage. This provides an environment in

which the pathogen is hidden from the immune system and allows it to

replicate.

Diseases with this type of behaviour include tuberculosis (caused by Mycobacterium tuberculosis) and leishmaniasis (caused by Leishmania species).

In order to minimize the possibility of becoming the host of an

intracellular bacteria, macrophages have evolved defense mechanisms such

as induction of nitric oxide and reactive oxygen intermediates, which

are toxic to microbes. Macrophages have also evolved the ability to

restrict the microbe's nutrient supply and induce autophagy.

Tuberculosis

Once engulfed by a macrophage, the causative agent of tuberculosis, Mycobacterium tuberculosis, avoids cellular defenses and uses the cell to replicate.

Leishmaniasis

Upon phagocytosis by a macrophage, the Leishmania

parasite finds itself in a phagocytic vacuole. Under normal

circumstances, this phagocytic vacuole would develop into a lysosome and

its contents would be digested. Leishmania alter this process and avoid being destroyed; instead, they make a home inside the vacuole.

Chikungunya

Infection of macrophages in joints is associated with local inflammation during and after the acute phase of Chikungunya (caused by CHIKV or Chikungunya virus).

Others

Adenovirus

(most common cause of pink eye) can remain latent in a host macrophage,

with continued viral shedding 6–18 months after initial infection.

Brucella spp. can remain latent in a macrophage via inhibition of phagosome–lysosome fusion; causes brucellosis (undulant fever).

Legionella pneumophila, the causative agent of Legionnaires' disease, also establishes residence within macrophages.

Heart disease

Macrophages are the predominant cells involved in creating the progressive plaque lesions of atherosclerosis.

Focal recruitment of macrophages occurs after the onset of acute myocardial infarction. These macrophages function to remove debris, apoptotic cells and to prepare for tissue regeneration.

HIV infection

Macrophages also play a role in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Like T cells,

macrophages can be infected with HIV, and even become a reservoir of

ongoing virus replication throughout the body. HIV can enter the

macrophage through binding of gp120 to CD4 and second membrane receptor,

CCR5 (a chemokine receptor). Both circulating monocytes and macrophages

serve as a reservoir for the virus.

Macrophages are better able to resist infection by HIV-1 than CD4+ T

cells, although susceptibility to HIV infection differs among macrophage

subtypes.

Cancer

Macrophages

can contribute to tumor growth and progression by promoting tumor cell

proliferation and invasion, fostering tumor angiogenesis and suppressing

antitumor immune cells. Attracted to oxygen-starved (hypoxic) and necrotic tumor cells they promote chronic inflammation. Inflammatory compounds such as tumor necrosis factor (TNF)-alpha released by the macrophages activate the gene switch nuclear factor-kappa B. NF-κB then enters the nucleus of a tumor cell and turns on production of proteins that stop apoptosis and promote cell proliferation and inflammation. Moreover, macrophages serve as a source for many pro-angiogenic factors including vascular endothelial factor (VEGF), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-alpha), Macrophage colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF/CSF1) and IL-1 and IL-6

contributing further to the tumor growth. Macrophages have been shown

to infiltrate a number of tumors. Their number correlates with poor

prognosis in certain cancers including cancers of breast, cervix,

bladder, brain and prostate.

Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) are thought to acquire an M2

phenotype, contributing to tumor growth and progression. Some tumors can

also produce factors, including M-CSF/CSF1, MCP-1/CCL2 and Angiotensin II, that trigger the amplification and mobilization of macrophages in tumors. Research in various study models suggests that macrophages can sometimes acquire anti-tumor functions. For example, macrophages may have cytotoxic activity

to kill tumor cells directly; also the co-operation of T-cells and

macrophages is important to suppress tumors. This co-operation involves

not only the direct contact of T-cell and macrophage, with antigen

presentation, but also includes the secretion of adequate combinations

of cytokines, which enhance T-cell antitumor activity.

Recent study findings suggest that by forcing IFN-α expression in

tumor-infiltrating macrophages, it is possible to blunt their innate

protumoral activity and reprogram the tumor microenvironment toward more

effective dendritic cell activation and immune effector cell

cytotoxicity.

Additionally, subcapsular sinus macrophages in tumor-draining lymph

nodes can suppress cancer progression by containing the spread of

tumor-derived materials.

Cancer therapy

Experimental studies indicate that macrophages can affect all therapeutic modalities, including surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, immunotherapy and targeted therapy.

Macrophages can influence treatment outcomes both positively and

negatively. Macrophages can be protective in different ways: they can

remove dead tumor cells (in a process called phagocytosis) following treatments that kill these cells; they can serve as drug depots for some anticancer drugs; they can also be activated by some therapies to promote antitumor immunity. Macrophages can also be deleterious in several ways: for example they can suppress various chemotherapies, radiotherapies and immunotherapies.

Because macrophages can regulate tumor progression, therapeutic

strategies to reduce the number of these cells, or to manipulate their

phenotypes, are currently being tested in cancer patients.

However, macrophages are also involved in antibody mediated

cytotoxicity (ADCC)and this mechanism has been proposed to be important

for certain cancer immunotherapy antibodies.

Obesity

It has

been observed that increased number of pro-inflammatory macrophages

within obese adipose tissue contributes to obesity complications

including insulin resistance and diabetes type 2.

Within the fat (adipose) tissue of CCR2 deficient mice, there is an increased number of eosinophils, greater alternative macrophage activation, and a propensity towards type 2 cytokine expression. Furthermore, this effect was exaggerated when the mice became obese from a high fat diet. This is partially caused by a phenotype switch of macrophages induced by necrosis of fat cells (adipocytes).

In an obese individual some adipocytes burst and undergo necrotic

death, which causes the residential M2 macrophages to switch to M1

phenotype. This is one of the causes of a low-grade systemic chronic

inflammatory state associated with obesity.

Intestinal macrophages

Though

very similar in structure to tissue macrophages, intestinal macrophages

have evolved specific characteristics and functions given their natural

environment, which is in the digestive tract. Macrophages and

intestinal macrophages have high plasticity causing their phenotype to

be altered by their environments. Like macrophages, intestinal macrophages are differentiated monocytes, though intestinal macrophages have to coexist with the microbiome

in the intestines. This is a challenge considering the bacteria found

in the gut are not recognized as "self" and could be potential targets

for phagocytosis by the macrophage.

To prevent the destruction of the gut bacteria, intestinal

macrophages have developed key differences compared to other

macrophages. Primarily, intestinal macrophages do not induce

inflammatory responses. Whereas tissue macrophages release various

inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-1, IL-6 and TNF-α, intestinal

macrophages do not produce or secrete inflammatory cytokines. This

change is directly caused by the intestinal macrophages environment.

Surrounding intestinal epithelial cells release TGF-β, which induces the change from proinflammatory macrophage to noninflammatory macrophage.

Even though the inflammatory response is downregulated in

intestinal macrophages, phagocytosis is still carried out. There is no

drop off in phagocytosis efficiency as intestinal macrophages are able

to effectively phagocytize the bacteria,S. typhimurium and E. coli,

but intestinal macrophages still do not release cytokines, even after

phagocytosis. Also, intestinal macrophages do not express

lipoplysaccharide (LPS), IgA, or IgG receptors.

The lack of LPS receptors is important for the gut as the intestinal

macrophages do not detect the microbe-associated molecular patterns (MAMPS/PAMPS) of the intestinal microbiome. Nor do they express IL-2 and IL-3 growth factor receptors.

Role in disease

Intestinal macrophages have been shown to play a role in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), such as Crohn's disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis

(UC). In a healthy gut, intestinal macrophages limit the inflammatory

response in the gut, but in a disease-state, intestinal macrophage

numbers and diversity are altered. This leads to inflammation of the gut

and disease symptoms of IBD. Intestinal macrophages are critical in

maintaining gut homeostasis. The presence of inflammation or pathogen alters this homeostasis, and concurrently alters the intestinal macrophages.

There has yet to be a determined mechanism for the alteration of the

intestinal macrophages by recruitment of new monocytes or changes in the

already present intestinal macrophages.