In planetary astronomy and astrobiology, the Rare Earth hypothesis argues that the origin of life and the evolution of biological complexity such as sexually reproducing, multicellular organisms on Earth (and, subsequently, human intelligence) required an improbable combination of astrophysical and geological events and circumstances.

According to the hypothesis, complex extraterrestrial life is an improbable phenomenon and likely to be rare. The term "Rare Earth" originates from Rare Earth: Why Complex Life Is Uncommon in the Universe (2000), a book by Peter Ward, a geologist and paleontologist, and Donald E. Brownlee, an astronomer and astrobiologist, both faculty members at the University of Washington.

In the 1970s and 1980s, Carl Sagan and Frank Drake, among others, argued that Earth is a typical rocky planet in a typical planetary system, located in a non-exceptional region of a common barred-spiral galaxy. From the principle of mediocrity (extended from the Copernican principle), they argued that we are typical, and the universe teems with complex life. However, Ward and Brownlee argue that planets, planetary systems, and galactic regions that are as friendly to complex life as the Earth, the Solar System, and our galactic region are rare.

Requirements for complex life

The Rare Earth hypothesis argues that the evolution of biological complexity requires a host of fortuitous circumstances, such as a galactic habitable zone, a central star and planetary system having the requisite character, the circumstellar habitable zone, a right-sized terrestrial planet, the advantage of a gas giant guardian like Jupiter and a large natural satellite, conditions needed to ensure the planet has a magnetosphere and plate tectonics, the chemistry of the lithosphere, atmosphere, and oceans, the role of "evolutionary pumps" such as massive glaciation and rare bolide impacts, and whatever led to the appearance of the eukaryote cell, sexual reproduction and the Cambrian explosion of animal, plant, and fungi phyla. The evolution of human intelligence may have required yet further events, which are extremely unlikely to have happened were it not for the Cretaceous–Paleogene extinction event 66 million years ago removing dinosaurs as the dominant terrestrial vertebrates.

In order for a small rocky planet to support complex life, Ward and Brownlee argue, the values of several variables must fall within narrow ranges. The universe is so vast that it could contain many Earth-like planets. But if such planets exist, they are likely to be separated from each other by many thousands of light years. Such distances may preclude communication among any intelligent species evolving on such planets, which would solve the Fermi paradox: "If extraterrestrial aliens are common, why aren't they obvious?"

The right location in the right kind of galaxy

Rare Earth suggests that much of the known universe, including large parts of our galaxy, are "dead zones" unable to support complex life. Those parts of a galaxy where complex life is possible make up the galactic habitable zone, primarily characterized by distance from the Galactic Center. As that distance increases:

- Star metallicity declines. Metals (which in astronomy means all elements other than hydrogen and helium) are necessary to the formation of terrestrial planets.

- The X-ray and gamma ray radiation from the black hole at the galactic center, and from nearby neutron stars, becomes less intense. Thus the early universe, and present-day galactic regions where stellar density is high and supernovae are common, will be dead zones.

- Gravitational perturbation of planets and planetesimals by nearby stars becomes less likely as the density of stars decreases. Hence the further a planet lies from the Galactic Center or a spiral arm, the less likely it is to be struck by a large bolide which could extinguish all complex life on a planet.

Item #1 rules out the outer reaches of a galaxy; #2 and #3 rule out galactic inner regions. Hence a galaxy's habitable zone may be a ring sandwiched between its uninhabitable center and outer reaches.

Also, a habitable planetary system must maintain its favorable location long enough for complex life to evolve. A star with an eccentric (elliptic or hyperbolic) galactic orbit will pass through some spiral arms, unfavorable regions of high star density; thus a life-bearing star must have a galactic orbit that is nearly circular, with a close synchronization between the orbital velocity of the star and of the spiral arms. This further restricts the galactic habitable zone within a fairly narrow range of distances from the Galactic Center. Lineweaver et al. calculate this zone to be a ring 7 to 9 kiloparsecs in radius, including no more than 10% of the stars in the Milky Way, about 20 to 40 billion stars. Gonzalez, et al. would halve these numbers; they estimate that at most 5% of stars in the Milky Way fall in the galactic habitable zone.

Approximately 77% of observed galaxies are spiral, two-thirds of all spiral galaxies are barred, and more than half, like the Milky Way, exhibit multiple arms. According to Rare Earth, our own galaxy is unusually quiet and dim (see below), representing just 7% of its kind. Even so, this would still represent more than 200 billion galaxies in the known universe.

Our galaxy also appears unusually favorable in suffering fewer collisions with other galaxies over the last 10 billion years, which can cause more supernovae and other disturbances. Also, the Milky Way's central black hole seems to have neither too much nor too little activity.

The orbit of the Sun around the center of the Milky Way is indeed almost perfectly circular, with a period of 226 Ma (million years), closely matching the rotational period of the galaxy. However, the majority of stars in barred spiral galaxies populate the spiral arms rather than the halo and tend to move in gravitationally aligned orbits, so there is little that is unusual about the Sun's orbit. While the Rare Earth hypothesis predicts that the Sun should rarely, if ever, have passed through a spiral arm since its formation, astronomer Karen Masters has calculated that the orbit of the Sun takes it through a major spiral arm approximately every 100 million years. Some researchers have suggested that several mass extinctions do correspond with previous crossings of the spiral arms.

Orbiting at the right distance from the right type of star

The terrestrial example suggests that complex life requires liquid water, requiring an orbital distance neither too close nor too far from the central star, another scale of habitable zone or Goldilocks Principle: The habitable zone varies with the star's type and age.

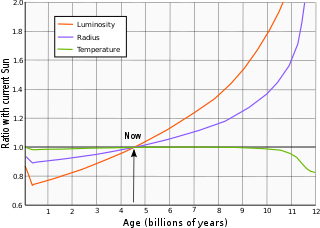

For advanced life, the star must also be highly stable, which is typical of middle star life, about 4.6 billion years old. Proper metallicity and size are also important to stability. The Sun has a low 0.1% luminosity variation. To date no solar twin star, with an exact match of the sun's luminosity variation, has been found, though some come close. The star must have no stellar companions, as in binary systems, which would disrupt the orbits of planets. Estimates suggest 50% or more of all star systems are binary. The habitable zone for a main sequence star very gradually moves out over its lifespan until it becomes a white dwarf and the habitable zone vanishes.

The liquid water and other gases available in the habitable zone bring the benefit of greenhouse warming. Even though the Earth's atmosphere

contains a water vapor concentration from 0% (in arid regions) to 4%

(in rain forest and ocean regions) and – as of February 2018 – only

408.05 parts per million of CO

2, these small amounts suffice to raise the average surface temperature by about 40 °C,

with the dominant contribution being due to water vapor, which together

with clouds makes up between 66% and 85% of Earth's greenhouse effect,

with CO

2 contributing between 9% and 26% of the effect.

Rocky planets must orbit within the habitable zone for life to form. Although the habitable zone of such hot stars as Sirius or Vega is wide, hot stars also emit much more ultraviolet radiation that ionizes any planetary atmosphere. They may become red giants before advanced life evolves on their planets. These considerations rule out the massive and powerful stars of type F6 to O (see stellar classification) as homes to evolved metazoan life.

Small red dwarf stars conversely have small habitable zones wherein planets are in tidal lock, with one very hot side always facing the star and another very cold side; and they are also at increased risk of solar flares (see Aurelia). Life probably cannot arise in such systems. Rare Earth proponents claim that only stars from F7 to K1 types are hospitable. Such stars are rare: G type stars such as the Sun (between the hotter F and cooler K) comprise only 9% of the hydrogen-burning stars in the Milky Way.

Such aged stars as red giants and white dwarfs are also unlikely to support life. Red giants are common in globular clusters and elliptical galaxies. White dwarfs are mostly dying stars that have already completed their red giant phase. Stars that become red giants expand into or overheat the habitable zones of their youth and middle age (though theoretically planets at a much greater distance may become habitable).

An energy output that varies with the lifetime of the star will likely prevent life (e.g., as Cepheid variables). A sudden decrease, even if brief, may freeze the water of orbiting planets, and a significant increase may evaporate it and cause a greenhouse effect that prevents the oceans from reforming.

All known life requires the complex chemistry of metallic elements. The absorption spectrum of a star reveals the presence of metals within, and studies of stellar spectra reveal that many, perhaps most, stars are poor in metals. Because heavy metals originate in supernova explosions, metallicity increases in the universe over time. Low metallicity characterizes the early universe: globular clusters and other stars that formed when the universe was young, stars in most galaxies other than large spirals, and stars in the outer regions of all galaxies. Metal-rich central stars capable of supporting complex life are therefore believed to be most common in the quiet suburbs of the larger spiral galaxies—where radiation also happens to be weak.

The right arrangement of planets

Rare Earth proponents argue that a planetary system capable of sustaining complex life must be structured more or less like the Solar System, with small and rocky inner planets and outer gas giants. Without the protection of 'celestial vacuum cleaner' planets with strong gravitational pull, a planet would be subject to more catastrophic asteroid collisions.

Observations of exo-planets have shown that arrangements of planets similar to the Solar System are rare. Most planetary systems have super Earths, several times larger than Earth, close to their star, whereas the Solar System's inner region has only a few small rocky planets and none inside Mercury's orbit. Only 10% of stars have giant planets similar to Jupiter and Saturn, and those few rarely have stable nearly circular orbits distant from their star. Konstantin Batygin and colleagues argue that these features can be explained if, early in the history of the Solar System, Jupiter and Saturn drifted towards the Sun, sending showers of planetesimals towards the super-Earths which sent them spiralling into the Sun, and ferrying icy building blocks into the terrestrial region of the Solar System which provided the building blocks for the rocky planets. The two giant planets then drifted out again to their present position. However, in the view of Batygin and his colleagues: "The concatenation of chance events required for this delicate choreography suggest that small, Earth-like rocky planets – and perhaps life itself – could be rare throughout the cosmos."

A continuously stable orbit

Rare Earth argues that a gas giant must not be too close to a body where life is developing. Close placement of gas giant(s) could disrupt the orbit of a potential life-bearing planet, either directly or by drifting into the habitable zone.

Newtonian dynamics can produce chaotic planetary orbits, especially in a system having large planets at high orbital eccentricity.

The need for stable orbits rules out stars with systems of planets that contain large planets with orbits close to the host star (called "hot Jupiters"). It is believed that hot Jupiters have migrated inwards to their current orbits. In the process, they would have catastrophically disrupted the orbits of any planets in the habitable zone. To exacerbate matters, hot Jupiters are much more common orbiting F and G class stars.

A terrestrial planet of the right size

It is argued that life requires terrestrial planets like Earth and as gas giants lack such a surface, that complex life cannot arise there.

A planet that is too small cannot hold much atmosphere, making surface temperature low and variable and oceans impossible. A small planet will also tend to have a rough surface, with large mountains and deep canyons. The core will cool faster, and plate tectonics may be brief or entirely absent. A planet that is too large will retain too dense an atmosphere like Venus. Although Venus is similar in size and mass to Earth, its surface atmospheric pressure is 92 times that of Earth, and surface temperature of 735 K (462 °C; 863 °F). Earth had a similar early atmosphere to Venus, but may have lost it in the giant impact event which formed the Moon.

With plate tectonics

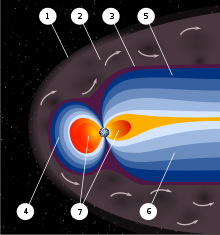

Rare Earth proponents argue that plate tectonics and a strong magnetic field are essential for biodiversity, global temperature regulation, and the carbon cycle. The lack of mountain chains elsewhere in the Solar System is direct evidence that Earth is the only body with plate tectonics, and thus the only nearby body capable of supporting life.

Plate tectonics depend on the right chemical composition and a long-lasting source of heat from radioactive decay. Continents must be made of less dense felsic rocks that "float" on underlying denser mafic rock. Taylor emphasizes that tectonic subduction zones require the lubrication of oceans of water. Plate tectonics also provides a means of biochemical cycling.

Plate tectonics and as a result continental drift and the creation of separate land masses would create diversified ecosystems and biodiversity, one of the strongest defences against extinction. An example of species diversification and later competition on Earth's continents is the Great American Interchange. North and Middle America drifted into South America at around 3.5 to 3 Ma. The fauna of South America evolved separately for about 30 million years, since Antarctica separated. Many species were subsequently wiped out in mainly South America by competing Northern American animals.

A large moon

The Moon is unusual because the other rocky planets in the Solar System either have no satellites (Mercury and Venus), or only tiny satellites which are probably captured asteroids (Mars).

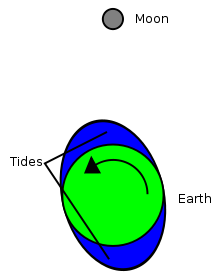

The Giant-impact theory hypothesizes that the Moon resulted from the impact of a Mars-sized body, dubbed Theia, with the young Earth. This giant impact also gave the Earth its axial tilt (inclination) and velocity of rotation. Rapid rotation reduces the daily variation in temperature and makes photosynthesis viable. The Rare Earth hypothesis further argues that the axial tilt cannot be too large or too small (relative to the orbital plane). A planet with a large tilt will experience extreme seasonal variations in climate. A planet with little or no tilt will lack the stimulus to evolution that climate variation provides. In this view, the Earth's tilt is "just right". The gravity of a large satellite also stabilizes the planet's tilt; without this effect the variation in tilt would be chaotic, probably making complex life forms on land impossible.

If the Earth had no Moon, the ocean tides resulting solely from the Sun's gravity would be only half that of the lunar tides. A large satellite gives rise to tidal pools, which may be essential for the formation of complex life, though this is far from certain.

A large satellite also increases the likelihood of plate tectonics through the effect of tidal forces on the planet's crust. The impact that formed the Moon may also have initiated plate tectonics, without which the continental crust would cover the entire planet, leaving no room for oceanic crust. It is possible that the large scale mantle convection needed to drive plate tectonics could not have emerged in the absence of crustal inhomogeneity. A further theory indicates that such a large moon may also contribute to maintaining a planet's magnetic shield by continually acting upon a metallic planetary core as dynamo, thus protecting the surface of the planet from charged particles and cosmic rays, and helping to ensure the atmosphere is not stripped over time by solar winds.

Atmosphere

A terrestrial planet of the right size is needed to retain an atmosphere, like Earth and Venus. On Earth, once the giant impact of Theia thinned Earth's atmosphere, other events were needed to make the atmosphere capable of sustaining life. The Late Heavy Bombardment reseeded Earth with water lost after the impact of Theia. The development of an ozone layer formed protection from ultraviolet (UV) sunlight. Nitrogen and carbon dioxide are needed in a correct ratio for life to form. Lightning is needed for nitrogen fixation. The carbon dioxide gas needed for life comes from sources such as volcanoes and geysers. Carbon dioxide is only needed at low levels (currently at 400 ppm); at high levels it is poisonous. Precipitation is needed to have a stable water cycle. A proper atmosphere must reduce diurnal temperature variation.

One or more evolutionary triggers for complex life

Regardless of whether planets with similar physical attributes to the Earth are rare or not, some argue that life usually remains simple bacteria. Biochemist Nick Lane argues that simple cells (prokaryotes) emerged soon after Earth's formation, but since almost half the planet's life had passed before they evolved into complex ones (eukaryotes) all of whom share a common ancestor, this event can only have happened once. In some views, prokaryotes lack the cellular architecture to evolve into eukaryotes because a bacterium expanded up to eukaryotic proportions would have tens of thousands of times less energy available; two billion years ago, one simple cell incorporated itself into another, multiplied, and evolved into mitochondria that supplied the vast increase in available energy that enabled the evolution of complex life. If this incorporation occurred only once in four billion years or is otherwise unlikely, then life on most planets remains simple. An alternative view is that mitochondria evolution was environmentally triggered, and that mitochondria-containing organisms appeared soon after the first traces of atmospheric oxygen.

The evolution and persistence of sexual reproduction is another mystery in biology. The purpose of sexual reproduction is unclear, as in many organisms it has a 50% cost (fitness disadvantage) in relation to asexual reproduction. Mating types (types of gametes, according to their compatibility) may have arisen as a result of anisogamy (gamete dimorphism), or the male and female sexes may have evolved before anisogamy. It is also unknown why most sexual organisms use a binary mating system, and why some organisms have gamete dimorphism. Charles Darwin was the first to suggest that sexual selection drives speciation; without it, complex life would probably not have evolved.

The right time in evolution

While life on Earth is regarded to have spawned relatively early in the planet's history, the evolution from multicellular to intelligent organisms took around 800 million years. Civilizations on Earth have existed for about 12,000 years and radio communication reaching space has existed for less than 100 years. Relative to the age of the Solar System (~4.57 Ga) this is a short time, in which extreme climatic variations, super volcanoes, and large meteorite impacts were absent. These events would severely harm intelligent life, as well as life in general. For example, the Permian-Triassic mass extinction, caused by widespread and continuous volcanic eruptions in an area the size of Western Europe, led to the extinction of 95% of known species around 251.2 Ma ago. About 65 million years ago, the Chicxulub impact at the Cretaceous–Paleogene boundary (~65.5 Ma) on the Yucatán peninsula in Mexico led to a mass extinction of the most advanced species at that time.

Rare Earth equation

The following discussion is adapted from Cramer. The Rare Earth equation is Ward and Brownlee's riposte to the Drake equation. It calculates , the number of Earth-like planets in the Milky Way having complex life forms, as:

where:

- N* is the number of stars in the Milky Way. This number is not well-estimated, because the Milky Way's mass is not well estimated, with little information about the number of small stars. N* is at least 100 billion, and may be as high as 500 billion, if there are many low visibility stars.

- is the average number of planets in a star's habitable zone. This zone is fairly narrow, because constrained by the requirement that the average planetary temperature be consistent with water remaining liquid throughout the time required for complex life to evolve. Thus =1 is a likely upper bound.

We assume . The Rare Earth hypothesis can then be viewed as asserting that the product of the other nine Rare Earth equation factors listed below, which are all fractions, is no greater than 10−10 and could plausibly be as small as 10−12. In the latter case, could be as small as 0 or 1. Ward and Brownlee do not actually calculate the value of , because the numerical values of quite a few of the factors below can only be conjectured. They cannot be estimated simply because we have but one data point: the Earth, a rocky planet orbiting a G2 star in a quiet suburb of a large barred spiral galaxy, and the home of the only intelligent species we know; namely, ourselves.

- is the fraction of stars in the galactic habitable zone (Ward, Brownlee, and Gonzalez estimate this factor as 0.1).

- is the fraction of stars in the Milky Way with planets.

- is the fraction of planets that are rocky ("metallic") rather than gaseous.

- is the fraction of habitable planets where microbial life arises. Ward and Brownlee believe this fraction is unlikely to be small.

- is the fraction of planets where complex life evolves. For 80% of the time since microbial life first appeared on the Earth, there was only bacterial life. Hence Ward and Brownlee argue that this fraction may be small.

- is the fraction of the total lifespan of a planet during which complex life is present. Complex life cannot endure indefinitely, because the energy put out by the sort of star that allows complex life to emerge gradually rises, and the central star eventually becomes a red giant, engulfing all planets in the planetary habitable zone. Also, given enough time, a catastrophic extinction of all complex life becomes ever more likely.

- is the fraction of habitable planets with a large moon. If the giant impact theory of the Moon's origin is correct, this fraction is small.

- is the fraction of planetary systems with large Jovian planets. This fraction could be large.

- is the fraction of planets with a sufficiently low number of extinction events. Ward and Brownlee argue that the low number of such events the Earth has experienced since the Cambrian explosion may be unusual, in which case this fraction would be small.

The Rare Earth equation, unlike the Drake equation, does not factor the probability that complex life evolves into intelligent life that discovers technology. Barrow and Tipler review the consensus among such biologists that the evolutionary path from primitive Cambrian chordates, e.g., Pikaia to Homo sapiens, was a highly improbable event. For example, the large brains of humans have marked adaptive disadvantages, requiring as they do an expensive metabolism, a long gestation period, and a childhood lasting more than 25% of the average total life span. Other improbable features of humans include:

- Being one of a handful of extant bipedal land (non-avian) vertebrate. Combined with an unusual eye–hand coordination, this permits dextrous manipulations of the physical environment with the hands;

- A vocal apparatus far more expressive than that of any other mammal, enabling speech. Speech makes it possible for humans to interact cooperatively, to share knowledge, and to acquire a culture;

- The capability of formulating abstractions to a degree permitting the invention of mathematics, and the discovery of science and technology. Only recently did humans acquire anything like their current scientific and technological sophistication.

Advocates

Writers who support the Rare Earth hypothesis:

- Stuart Ross Taylor, a specialist on the Solar System, firmly believes in the hypothesis. Taylor concludes that the Solar System is probably unusual, because it resulted from so many chance factors and events.

- Stephen Webb, a physicist, mainly presents and rejects candidate solutions for the Fermi paradox. The Rare Earth hypothesis emerges as one of the few solutions left standing by the end of the book

- Simon Conway Morris, a paleontologist, endorses the Rare Earth hypothesis in chapter 5 of his Life's Solution: Inevitable Humans in a Lonely Universe, and cites Ward and Brownlee's book with approval.

- John D. Barrow and Frank J. Tipler (1986. 3.2, 8.7, 9), cosmologists, vigorously defend the hypothesis that humans are likely to be the only intelligent life in the Milky Way, and perhaps the entire universe. But this hypothesis is not central to their book The Anthropic Cosmological Principle, a thorough study of the anthropic principle and of how the laws of physics are peculiarly suited to enable the emergence of complexity in nature.

- Ray Kurzweil, a computer pioneer and self-proclaimed Singularitarian, argues in The Singularity Is Near that the coming Singularity requires that Earth be the first planet on which sapient, technology-using life evolved. Although other Earth-like planets could exist, Earth must be the most evolutionarily advanced, because otherwise we would have seen evidence that another culture had experienced the Singularity and expanded to harness the full computational capacity of the physical universe.

- John Gribbin, a prolific science writer, defends the hypothesis in Alone in the Universe: Why our planet is unique.

- Guillermo Gonzalez, astrophysicist who supports the concept of galactic habitable zone uses the hypothesis in his book The Privileged Planet to promote the concept of intelligent design.

- Michael H. Hart, astrophysicist who proposed a narrow habitable zone based on climate studies, edited the influential book Extraterrestrials: Where are They and authored one of its chapters "Atmospheric Evolution, the Drake Equation and DNA: Sparse Life in an Infinite Universe".

- Howard Alan Smith, astrophysicist and author of 'Let there be light: modern cosmology and Kabbalah: a new conversation between science and religion'.

- Marc J. Defant, professor of geochemistry and volcanology, elaborated on several aspects of the rare earth hypothesis in his TEDx talk entitled: Why We are Alone in the Galaxy.

- Brian Cox, physicist and popular science celebrity confesses his support for the hypothesis in his BBC production of the Human Universe.

Criticism

Cases against the Rare Earth hypothesis take various forms.

The hypothesis appears anthropocentric

The hypothesis concludes, more or less, that complex life is rare because it can evolve only on the surface of an Earth-like planet or on a suitable satellite of a planet. Some biologists, such as Jack Cohen, believe this assumption too restrictive and unimaginative; they see it as a form of circular reasoning.

According to David Darling, the Rare Earth hypothesis is neither hypothesis nor prediction, but merely a description of how life arose on Earth. In his view, Ward and Brownlee have done nothing more than select the factors that best suit their case.

What matters is not whether there's anything unusual about the Earth; there's going to be something idiosyncratic about every planet in space. What matters is whether any of Earth's circumstances are not only unusual but also essential for complex life. So far we've seen nothing to suggest there is.

Critics also argue that there is a link between the Rare Earth hypothesis and the unscientific idea of intelligent design.

Exoplanets around main sequence stars are being discovered in large numbers

An increasing number of extrasolar planet discoveries are being made with 4,704 planets in 3,478 planetary systems known as of 1 April 2021. Rare Earth proponents argue life cannot arise outside Sun-like systems, due to tidal locking and ionizing radiation outside the F7–K1 range. However, some exobiologists have suggested that stars outside this range may give rise to life under the right circumstances; this possibility is a central point of contention to the theory because these late-K and M category stars make up about 82% of all hydrogen-burning stars.

Current technology limits the testing of important Rare Earth criteria: surface water, tectonic plates, a large moon and biosignatures are currently undetectable. Though planets the size of Earth are difficult to detect and classify, scientists now think that rocky planets are common around Sun-like stars. The Earth Similarity Index (ESI) of mass, radius and temperature provides a means of measurement, but falls short of the full Rare Earth criteria.

Rocky planets orbiting within habitable zones may not be rare

Some argue that Rare Earth's estimates of rocky planets in habitable zones ( in the Rare Earth equation) are too restrictive. James Kasting cites the Titius-Bode law to contend that it is a misnomer to describe habitable zones as narrow when there is a 50% chance of at least one planet orbiting within one. In 2013, astronomers using the Kepler space telescope's data estimated that about one-fifth of G-type and K-type stars (sun-like stars and orange dwarves) are expected to have an Earth-sized or super-Earth-sized planet (1–2 Earths wide) close to an Earth-like orbit (0.25–4 F⊕), yielding about 8.8 billion of them for the entire Milky Way Galaxy.

Uncertainty over Jupiter's role

The requirement for a system to have a Jovian planet as protector (Rare Earth equation factor ) has been challenged, affecting the number of proposed extinction events (Rare Earth equation factor ). Kasting's 2001 review of Rare Earth questions whether a Jupiter protector has any bearing on the incidence of complex life. Computer modelling including the 2005 Nice model and 2007 Nice 2 model yield inconclusive results in relation to Jupiter's gravitational influence and impacts on the inner planets. A study by Horner and Jones (2008) using computer simulation found that while the total effect on all orbital bodies within the Solar System is unclear, Jupiter has caused more impacts on Earth than it has prevented. Lexell's Comet, a 1770 near miss that passed closer to Earth than any other comet in recorded history, was known to be caused by the gravitational influence of Jupiter. Grazier (2017) claims that the idea of Jupiter as a shield is a misinterpretation of a 1996 study by George Wetherill, and using computer models Grazier was able to demonstrate that Saturn protects Earth from more asteroids and comets than does Jupiter.

Plate tectonics may not be unique to Earth or a requirement for complex life

Ward and Brownlee argue that for complex life to evolve (Rare Earth equation factor ), tectonics must be present to generate biogeochemical cycles, and predicted that such geological features would not be found outside of Earth, pointing to a lack of observable mountain ranges and subduction. There is, however, no scientific consensus on the evolution of plate tectonics on Earth. Though it is believed that tectonic motion first began around three billion years ago, by this time photosynthesis and oxygenation had already begun. Furthermore, recent studies point to plate tectonics as an episodic planetary phenomenon, and that life may evolve during periods of "stagnant-lid" rather than plate tectonic states.

Recent evidence also points to similar activity either having occurred or continuing to occur elsewhere. The geology of Pluto, for example, described by Ward and Brownlee as "without mountains or volcanoes ... devoid of volcanic activity", has since been found to be quite the contrary, with a geologically active surface possessing organic molecules and mountain ranges like Tenzing Montes and Hillary Montes comparable in relative size to those of Earth, and observations suggest the involvement of endogenic processes. Plate tectonics has been suggested as a hypothesis for the Martian dichotomy, and in 2012 geologist An Yin put forward evidence for active plate tectonics on Mars. Europa has long been suspected to have plate tectonics and in 2014 NASA announced evidence of active subduction. In 2017, scientists studying the geology of Charon confirmed that icy plate tectonics also operated on Pluto's largest moon.

Kasting suggests that there is nothing unusual about the occurrence of plate tectonics in large rocky planets and liquid water on the surface as most should generate internal heat even without the assistance of radioactive elements. Studies by Valencia and Cowan suggest that plate tectonics may be inevitable for terrestrial planets Earth sized or larger, that is, Super-Earths, which are now known to be more common in planetary systems.

Free oxygen may be neither rare nor a prerequisite for multicellular life

The hypothesis that molecular oxygen, necessary for animal life, is rare and that a Great Oxygenation Event (Rare Earth equation factor ) could only have been triggered and sustained by tectonics, appears to have been invalidated by more recent discoveries.

Ward and Brownlee ask "whether oxygenation, and hence the rise of animals, would ever have occurred on a world where there were no continents to erode". Extraterrestrial free oxygen has recently been detected around other solid objects, including Mercury, Venus, Mars, Jupiter's four Galilean moons, Saturn's moons Enceladus, Dione and Rhea and even the atmosphere of a comet. This has led scientists to speculate whether processes other than photosynthesis could be capable of generating an environment rich in free oxygen. Wordsworth (2014) concludes that oxygen generated other than through photodissociation may be likely on Earth-like exoplanets, and could actually lead to false positive detections of life. Narita (2015) suggests photocatalysis by titanium dioxide as a geochemical mechanism for producing oxygen atmospheres.

Since Ward & Brownlee's assertion that "there is irrefutable evidence that oxygen is a necessary ingredient for animal life", anaerobic metazoa have been found that indeed do metabolise without oxygen. Spinoloricus cinziae, for example, a species discovered in the hypersaline anoxic L'Atalante basin at the bottom of the Mediterranean Sea in 2010, appears to metabolise with hydrogen, lacking mitochondria and instead using hydrogenosomes. Studies since 2015 of the eukaryotic genus Monocercomonoides that lack mitochondrial organelles are also significant as there are no detectable signs that mitochondria were ever part of the organism. Since then further eukaryotes, particularly parasites, have been identified to be completely absent of mitochondrial genome, such as the 2020 discovery in Henneguya zschokkei. Further investigation into alternative metabolic pathways used by these organisms appear to present further problems for the premise.

Stevenson (2015) has proposed other membrane alternatives for complex life in worlds without oxygen. In 2017, scientists from the NASA Astrobiology Institute discovered the necessary chemical preconditions for the formation of azotosomes on Saturn's moon Titan, a world that lacks atmospheric oxygen. Independent studies by Schirrmeister and by Mills concluded that Earth's multicellular life existed prior to the Great Oxygenation Event, not as a consequence of it.

NASA scientists Hartman and McKay argue that plate tectonics may in fact slow the rise of oxygenation (and thus stymie complex life rather than promote it). Computer modelling by Tilman Spohn in 2014 found that plate tectonics on Earth may have arisen from the effects of complex life's emergence, rather than the other way around as the Rare Earth might suggest. The action of lichens on rock may have contributed to the formation of subduction zones in the presence of water. Kasting argues that if oxygenation caused the Cambrian explosion then any planet with oxygen producing photosynthesis should have complex life.

A magnetic field may not be a requirement

The importance of Earth's magnetic field to the development of complex life has been disputed. Kasting argues that the atmosphere provides sufficient protection against cosmic rays even during times of magnetic pole reversal and atmosphere loss by sputtering. Kasting also dismisses the role of the magnetic field in the evolution of eukaryotes, citing the age of the oldest known magnetofossils.

A large moon may be neither rare nor necessary

The requirement of a large moon (Rare Earth equation factor ) has also been challenged. Even if it were required, such an occurrence may not be as unique as predicted by the Rare Earth Hypothesis. Recent work by Edward Belbruno and J. Richard Gott of Princeton University suggests that giant impactors such as those that may have formed the Moon can indeed form in planetary trojan points (L4 or L5 Lagrangian point) which means that similar circumstances may occur in other planetary systems.

The assertion that the Moon's stabilization of Earth's obliquity and spin is a requirement for complex life has been questioned. Kasting argues that a moonless Earth would still possess habitats with climates suitable for complex life and questions whether the spin rate of a moonless Earth can be predicted. Although the giant impact theory posits that the impact forming the Moon increased Earth's rotational speed to make a day about 5 hours long, the Moon has slowly "stolen" much of this speed to reduce Earth's solar day since then to about 24 hours and continues to do so: in 100 million years Earth's solar day will be roughly 24 hours 38 minutes (the same as Mars's solar day); in 1 billion years, 30 hours 23 minutes. Larger secondary bodies would exert proportionally larger tidal forces that would in turn decelerate their primaries faster and potentially increase the solar day of a planet in all other respects like Earth to over 120 hours within a few billion years. This long solar day would make effective heat dissipation for organisms in the tropics and subtropics extremely difficult in a similar manner to tidal locking to a red dwarf star. Short days (high rotation speed) cause high wind speeds at ground level. Long days (slow rotation speed) cause the day and night temperatures to be too extreme.

Many Rare Earth proponents argue that the Earth's plate tectonics would probably not exist if not for the tidal forces of the Moon. The hypothesis that the Moon's tidal influence initiated or sustained Earth's plate tectonics remains unproven, though at least one study implies a temporal correlation to the formation of the Moon. Evidence for the past existence of plate tectonics on planets like Mars which may never have had a large moon would counter this argument. Kasting argues that a large moon is not required to initiate plate tectonics.

Complex life may arise in alternative habitats

Rare Earth proponents argue that simple life may be common, though complex life requires specific environmental conditions to arise. Critics consider life could arise on a moon of a gas giant, though this is less likely if life requires volcanicity. The moon must have stresses to induce tidal heating, but not so dramatic as seen on Jupiter's Io. However, the moon is within the gas giant's intense radiation belts, sterilizing any biodiversity before it can get established. Dirk Schulze-Makuch disputes this, hypothesizing alternative biochemistries for alien life. While Rare Earth proponents argue that only microbial extremophiles could exist in subsurface habitats beyond Earth, some argue that complex life can also arise in these environments. Examples of extremophile animals such as the Hesiocaeca methanicola, an animal that inhabits ocean floor methane clathrates substances more commonly found in the outer Solar System, the tardigrades which can survive in the vacuum of space or Halicephalobus mephisto which exists in crushing pressure, scorching temperatures and extremely low oxygen levels 3.6 kilometres deep in the Earth's crust, are sometimes cited by critics as complex life capable of thriving in "alien" environments. Jill Tarter counters the classic counterargument that these species adapted to these environments rather than arose in them, by suggesting that we cannot assume conditions for life to emerge which are not actually known. There are suggestions that complex life could arise in sub-surface conditions which may be similar to those where life may have arisen on Earth, such as the tidally heated subsurfaces of Europa or Enceladus. Ancient circumvental ecosystems such as these support complex life on Earth such as Riftia pachyptila that exist completely independent of the surface biosphere.