The DNA damage theory of aging proposes that aging is a consequence of unrepaired accumulation of naturally occurring DNA damage. Damage in this context is a DNA alteration that has an abnormal structure. Although both mitochondrial and nuclear DNA damage can contribute to aging, nuclear DNA is the main subject of this analysis. Nuclear DNA damage can contribute to aging either indirectly (by increasing apoptosis or cellular senescence) or directly (by increasing cell dysfunction).

Several review articles have shown that deficient DNA repair, allowing greater accumulation of DNA damage, causes premature aging; and that increased DNA repair facilitates greater longevity. Mouse models of nucleotide-excision–repair syndromes reveal a striking correlation between the degree to which specific DNA repair pathways are compromised and the severity of accelerated aging, strongly suggesting a causal relationship. Human population studies show that single-nucleotide polymorphisms in DNA repair genes, causing up-regulation of their expression, correlate with increases in longevity. Lombard et al. compiled a lengthy list of mouse mutational models with pathologic features of premature aging, all caused by different DNA repair defects. Freitas and de Magalhães presented a comprehensive review and appraisal of the DNA damage theory of aging, including a detailed analysis of many forms of evidence linking DNA damage to aging. As an example, they described a study showing that centenarians of 100 to 107 years of age had higher levels of two DNA repair enzymes, PARP1 and Ku70, than general-population old individuals of 69 to 75 years of age. Their analysis supported the hypothesis that improved DNA repair leads to longer life span. Overall, they concluded that while the complexity of responses to DNA damage remains only partly understood, the idea that DNA damage accumulation with age is the primary cause of aging remains an intuitive and powerful one.

In humans and other mammals, DNA damage occurs frequently and DNA repair processes have evolved to compensate. In estimates made for mice, DNA lesions occur on average 25 to 115 times per minute in each cell, or about 36,000 to 160,000 per cell per day. Some DNA damage may remain in any cell despite the action of repair processes. The accumulation of unrepaired DNA damage is more prevalent in certain types of cells, particularly in non-replicating or slowly replicating cells, such as cells in the brain, skeletal and cardiac muscle.

DNA damage and mutation

To understand the DNA damage theory of aging it is important to distinguish between DNA damage and mutation, the two major types of errors that occur in DNA. Damage and mutation are fundamentally different. DNA damage is any physical abnormality in the DNA, such as single and double strand breaks, 8-hydroxydeoxyguanosine residues and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon adducts. DNA damage can be recognized by enzymes, and thus can be correctly repaired using the complementary undamaged sequence in a homologous chromosome if it is available for copying. If a cell retains DNA damage, transcription of a gene can be prevented and thus translation into a protein will also be blocked. Replication may also be blocked and/or the cell may die. Descriptions of reduced function, characteristic of aging and associated with accumulation of DNA damage, are given later in this article.

In contrast to DNA damage, a mutation is a change in the base sequence of the DNA. A mutation cannot be recognized by enzymes once the base change is present in both DNA strands, and thus a mutation cannot be repaired. At the cellular level, mutations can cause alterations in protein function and regulation. Mutations are replicated when the cell replicates. In a population of cells, mutant cells will increase or decrease in frequency according to the effects of the mutation on the ability of the cell to survive and reproduce. Although distinctly different from each other, DNA damages and mutations are related because DNA damages often cause errors of DNA synthesis during replication or repair and these errors are a major source of mutation.

Given these properties of DNA damage and mutation, it can be seen that DNA damages are a special problem in non-dividing or slowly dividing cells, where unrepaired damages will tend to accumulate over time. On the other hand, in rapidly dividing cells, unrepaired DNA damages that do not kill the cell by blocking replication will tend to cause replication errors and thus mutation. The great majority of mutations that are not neutral in their effect are deleterious to a cell's survival. Thus, in a population of cells comprising a tissue with replicating cells, mutant cells will tend to be lost. However, infrequent mutations that provide a survival advantage will tend to clonally expand at the expense of neighboring cells in the tissue. This advantage to the cell is disadvantageous to the whole organism, because such mutant cells can give rise to cancer. Thus DNA damages in frequently dividing cells, because they give rise to mutations, are a prominent cause of cancer. In contrast, DNA damages in infrequently dividing cells are likely a prominent cause of aging.

The first person to suggest that DNA damage, as distinct from mutation, is the primary cause of aging was Alexander in 1967. By the early 1980s there was significant experimental support for this idea in the literature. By the early 1990s experimental support for this idea was substantial, and furthermore it had become increasingly evident that oxidative DNA damage, in particular, is a major cause of aging.

In a series of articles from 1970 to 1977, PV Narasimh Acharya, Phd. (1924–1993) theorized and presented evidence that cells undergo "irreparable DNA damage", whereby DNA crosslinks occur when both normal cellular repair processes fail and cellular apoptosis does not occur. Specifically, Acharya noted that double-strand breaks and a "cross-linkage joining both strands at the same point is irreparable because neither strand can then serve as a template for repair. The cell will die in the next mitosis or in some rare instances, mutate."

Age-associated accumulation of DNA damage and decline in gene expression

In tissues composed of non- or infrequently replicating cells, DNA damage can accumulate with age and lead either to loss of cells, or, in surviving cells, loss of gene expression. Accumulated DNA damage is usually measured directly. Numerous studies of this type have indicated that oxidative damage to DNA is particularly important. The loss of expression of specific genes can be detected at both the mRNA level and protein level.

Brain

The adult brain is composed in large part of terminally differentiated non-dividing neurons. Many of the conspicuous features of aging reflect a decline in neuronal function. Accumulation of DNA damage with age in the mammalian brain has been reported during the period 1971 to 2008 in at least 29 studies. This DNA damage includes the oxidized nucleoside 8-oxo-2'-deoxyguanosine (8-oxo-dG), single- and double-strand breaks, DNA-protein crosslinks and malondialdehyde adducts (reviewed in Bernstein et al.). Increasing DNA damage with age has been reported in the brains of the mouse, rat, gerbil, rabbit, dog, and human.

Rutten et al. showed that single-strand breaks accumulate in the mouse brain with age. Young 4-day-old rats have about 3,000 single-strand breaks and 156 double-strand breaks per neuron, whereas in rats older than 2 years the level of damage increases to about 7,400 single-strand breaks and 600 double-strand breaks per neuron. Sen et al. showed that DNA damages which block the polymerase chain reaction in rat brain accumulate with age. Swain and Rao observed marked increases in several types of DNA damages in aging rat brain, including single-strand breaks, double-strand breaks and modified bases (8-OHdG and uracil). Wolf et al. also showed that the oxidative DNA damage 8-OHdG accumulates in rat brain with age. Similarly, it was shown that as humans age from 48 to 97 years, 8-OHdG accumulates in the brain.

Lu et al. studied the transcriptional profiles of the human frontal cortex of individuals ranging from 26 to 106 years of age. This led to the identification of a set of genes whose expression was altered after age 40. These genes play central roles in synaptic plasticity, vesicular transport and mitochondrial function. In the brain, promoters of genes with reduced expression have markedly increased DNA damage. In cultured human neurons, these gene promoters are selectively damaged by oxidative stress. Thus Lu et al. concluded that DNA damage may reduce the expression of selectively vulnerable genes involved in learning, memory and neuronal survival, initiating a program of brain aging that starts early in adult life.

Muscle

Muscle strength, and stamina for sustained physical effort, decline in function with age in humans and other species. Skeletal muscle is a tissue composed largely of multinucleated myofibers, elements that arise from the fusion of mononucleated myoblasts. Accumulation of DNA damage with age in mammalian muscle has been reported in at least 18 studies since 1971. Hamilton et al. reported that the oxidative DNA damage 8-OHdG accumulates in heart and skeletal muscle (as well as in brain, kidney and liver) of both mouse and rat with age. In humans, increases in 8-OHdG with age were reported for skeletal muscle. Catalase is an enzyme that removes hydrogen peroxide, a reactive oxygen species, and thus limits oxidative DNA damage. In mice, when catalase expression is increased specifically in mitochondria, oxidative DNA damage (8-OHdG) in skeletal muscle is decreased and lifespan is increased by about 20%. These findings suggest that mitochondria are a significant source of the oxidative damages contributing to aging.

Protein synthesis and protein degradation decline with age in skeletal and heart muscle, as would be expected, since DNA damage blocks gene transcription. In 2005, Piec et al. found numerous changes in protein expression in rat skeletal muscle with age, including lower levels of several proteins related to myosin and actin. Force is generated in striated muscle by the interactions between myosin thick filaments and actin thin filaments.

Liver

Liver hepatocytes do not ordinarily divide and appear to be terminally differentiated, but they retain the ability to proliferate when injured. With age, the mass of the liver decreases, blood flow is reduced, metabolism is impaired, and alterations in microcirculation occur. At least 21 studies have reported an increase in DNA damage with age in liver. For instance, Helbock et al. estimated that the steady state level of oxidative DNA base alterations increased from 24,000 per cell in the liver of young rats to 66,000 per cell in the liver of old rats.

Kidney

In kidney, changes with age include reduction in both renal blood flow and glomerular filtration rate, and impairment in the ability to concentrate urine and to conserve sodium and water. DNA damages, particularly oxidative DNA damages, increase with age (at least 8 studies). For instance Hashimoto et al. showed that 8-OHdG accumulates in rat kidney DNA with age.

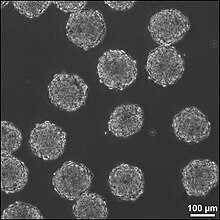

Long-lived stem cells

Tissue-specific stem cells produce differentiated cells through a series of increasingly more committed progenitor intermediates. In hematopoiesis (blood cell formation), the process begins with long-term hematopoietic stem cells that self-renew and also produce progeny cells that upon further replication go through a series of stages leading to differentiated cells without self-renewal capacity. In mice, deficiencies in DNA repair appear to limit the capacity of hematopoietic stem cells to proliferate and self-renew with age. Sharpless and Depinho reviewed evidence that hematopoietic stem cells, as well as stem cells in other tissues, undergo intrinsic aging. They speculated that stem cells grow old, in part, as a result of DNA damage. DNA damage may trigger signalling pathways, such as apoptosis, that contribute to depletion of stem cell stocks. This has been observed in several cases of accelerated aging and may occur in normal aging too.

A key aspect of hair loss with age is the aging of the hair follicle. Ordinarily, hair follicle renewal is maintained by the stem cells associated with each follicle. Aging of the hair follicle appears to be due to the DNA damage that accumulates in renewing stem cells during aging.

Mutation theories of aging

A popular idea, that has failed to gain significant experimental support, is the idea that mutation, as distinct from DNA damage, is the primary cause of aging. As discussed above, mutations tend to arise in frequently replicating cells as a result of errors of DNA synthesis when template DNA is damaged, and can give rise to cancer. However, in mice there is no increase in mutation in the brain with aging. Mice defective in a gene (Pms2) that ordinarily corrects base mispairs in DNA have about a 100-fold elevated mutation frequency in all tissues, but do not appear to age more rapidly. On the other hand, mice defective in one particular DNA repair pathway show clear premature aging, but do not have elevated mutation.

One variation of the idea that mutation is the basis of aging, that has received much attention, is that mutations specifically in mitochondrial DNA are the cause of aging. Several studies have shown that mutations accumulate in mitochondrial DNA in infrequently replicating cells with age. DNA polymerase gamma is the enzyme that replicates mitochondrial DNA. A mouse mutant with a defect in this DNA polymerase is only able to replicate its mitochondrial DNA inaccurately, so that it sustains a 500-fold higher mutation burden than normal mice. These mice showed no clear features of rapidly accelerated aging. Overall, the observations discussed in this section indicate that mutations are not the primary cause of aging.

Dietary restriction

In rodents, caloric restriction slows aging and extends lifespan. At least 4 studies have shown that caloric restriction reduces 8-OHdG damages in various organs of rodents. One of these studies showed that caloric restriction reduced accumulation of 8-OHdG with age in rat brain, heart and skeletal muscle, and in mouse brain, heart, kidney and liver. More recently, Wolf et al. showed that dietary restriction reduced accumulation of 8-OHdG with age in rat brain, heart, skeletal muscle, and liver. Thus reduction of oxidative DNA damage is associated with a slower rate of aging and increased lifespan.

Inherited defects that cause premature aging

If DNA damage is the underlying cause of aging, it would be expected that humans with inherited defects in the ability to repair DNA damages should age at a faster pace than persons without such a defect. Numerous examples of rare inherited conditions with DNA repair defects are known. Several of these show multiple striking features of premature aging, and others have fewer such features. Perhaps the most striking premature aging conditions are Werner syndrome (mean lifespan 47 years), Huchinson–Gilford progeria (mean lifespan 13 years), and Cockayne syndrome (mean lifespan 13 years).

Werner syndrome is due to an inherited defect in an enzyme (a helicase and exonuclease) that acts in base excision repair of DNA (e.g. see Harrigan et al.).

Huchinson–Gilford progeria is due to a defect in Lamin A protein which forms a scaffolding within the cell nucleus to organize chromatin and is needed for repair of double-strand breaks in DNA. A-type lamins promote genetic stability by maintaining levels of proteins that have key roles in the DNA repair processes of non-homologous end joining and homologous recombination. Mouse cells deficient for maturation of prelamin A show increased DNA damage and chromosome aberrations and are more sensitive to DNA damaging agents.

Cockayne Syndrome is due to a defect in a protein necessary for the repair process, transcription coupled nucleotide excision repair, which can remove damages, particularly oxidative DNA damages, that block transcription.

In addition to these three conditions, several other human syndromes, that also have defective DNA repair, show several features of premature aging. These include ataxia–telangiectasia, Nijmegen breakage syndrome, some subgroups of xeroderma pigmentosum, trichothiodystrophy, Fanconi anemia, Bloom syndrome and Rothmund–Thomson syndrome.

In addition to human inherited syndromes, experimental mouse models with genetic defects in DNA repair show features of premature aging and reduced lifespan. In particular, mutant mice defective in Ku70, or Ku80, or double mutant mice deficient in both Ku70 and Ku80 exhibit early aging. The mean lifespans of the three mutant mouse strains were similar to each other, at about 37 weeks, compared to 108 weeks for the wild-type control. Six specific signs of aging were examined, and the three mutant mice were found to display the same aging signs as the control mice, but at a much earlier age. Cancer incidence was not increased in the mutant mice. Ku70 and Ku80 form the heterodimer Ku protein essential for the non-homologous end joining (NHEJ) pathway of DNA repair, active in repairing DNA double-strand breaks. This suggests an important role of NHEJ in longevity assurance.

Defects in DNA repair cause features of premature aging

Many authors have noted an association between defects in the DNA damage response and premature aging (see e.g.). If a DNA repair protein is deficient, unrepaired DNA damages tend to accumulate. Such accumulated DNA damages appear to cause features of premature aging (segmental progeria).

Lifespan in different mammalian species

Studies comparing DNA repair capacity in different mammalian species have shown that repair capacity correlates with lifespan. The initial study of this type, by Hart and Setlow, showed that the ability of skin fibroblasts of seven mammalian species to perform DNA repair after exposure to a DNA damaging agent correlated with lifespan of the species. The species studied were shrew, mouse, rat, hamster, cow, elephant and human. This initial study stimulated many additional studies involving a wide variety of mammalian species, and the correlation between repair capacity and lifespan generally held up. In one of the more recent studies, Burkle et al. studied the level of a particular enzyme, Poly ADP ribose polymerase, which is involved in repair of single-strand breaks in DNA. They found that the lifespan of 13 mammalian species correlated with the activity of this enzyme.

The DNA repair transcriptomes of the liver of humans, naked mole-rats and mice were compared. The maximum lifespans of humans, naked mole-rat, and mouse are respectively ~120, 30 and 3 years. The longer-lived species, humans and naked mole rats expressed DNA repair genes, including core genes in several DNA repair pathways, at a higher level than did mice. In addition, several DNA repair pathways in humans and naked mole-rats were up-regulated compared with mouse. These findings suggest that increased DNA repair facilitates greater longevity.

Over the past decade, a series of papers have shown that the mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) base composition correlates with animal species maximum life span. The mitochondrial DNA base composition is thought to reflect its nucleotide-specific (guanine, cytosine, thymidine and adenine) different mutation rates (i.e., accumulation of guanine in the mitochondrial DNA of an animal species is due to low guanine mutation rate in the mitochondria of that species).

Centenarians

Lymphoblastoid cell lines established from blood samples of humans who lived past 100 years (centenarians) have significantly higher activity of the DNA repair protein Poly (ADP-ribose) polymerase (PARP) than cell lines from younger individuals (20 to 70 years old). The lymphocytic cells of centenarians have characteristics typical of cells from young people, both in their capability of priming the mechanism of repair after H2O2 sublethal oxidative DNA damage and in their PARP capacity.

Menopause

As women age, they experience a decline in reproductive performance leading to menopause. This decline is tied to a decline in the number of ovarian follicles. Although 6 to 7 million oocytes are present at mid-gestation in the human ovary, only about 500 (about 0.05%) of these ovulate, and the rest are lost. The decline in ovarian reserve appears to occur at an increasing rate with age, and leads to nearly complete exhaustion of the reserve by about age 51. As ovarian reserve and fertility decline with age, there is also a parallel increase in pregnancy failure and meiotic errors resulting in chromosomally abnormal conceptions.

BRCA1 and BRCA2 are homologous recombination repair genes. The role of declining ATM-Mediated DNA double strand DNA break (DSB) repair in oocyte aging was first proposed by Kutluk Oktay, MD, PhD based on his observations that women with BRCA mutations produced fewer oocytes in response to ovarian stimulation repair. His laboratory has further studied this hypothesis and provided an explanation for the decline in ovarian reserve with age. They showed that as women age, double-strand breaks accumulate in the DNA of their primordial follicles. Primordial follicles are immature primary oocytes surrounded by a single layer of granulosa cells. An enzyme system is present in oocytes that normally accurately repairs DNA double-strand breaks. This repair system is referred to as homologous recombinational repair, and it is especially active during meiosis. Titus et al. from Oktay Laboratory also showed that expression of four key DNA repair genes that are necessary for homologous recombinational repair (BRCA1, MRE11, Rad51 and ATM) decline in oocytes with age. This age-related decline in ability to repair double-strand damages can account for the accumulation of these damages, which then likely contributes to the decline in ovarian reserve as further explained by Turan and Oktay.

Women with an inherited mutation in the DNA repair gene BRCA1 undergo menopause prematurely, suggesting that naturally occurring DNA damages in oocytes are repaired less efficiently in these women, and this inefficiency leads to early reproductive failure. Genomic data from about 70,000 women were analyzed to identify protein-coding variation associated with age at natural menopause. Pathway analyses identified a major association with DNA damage response genes, particularly those expressed during meiosis and including a common coding variant in the BRCA1 gene.

Atherosclerosis

The most important risk factor for cardiovascular problems is chronological aging. Several research groups have reviewed evidence for a key role of DNA damage in vascular aging.

Atherosclerotic plaque contains vascular smooth muscle cells, macrophages and endothelial cells and these have been found to accumulate 8-oxoG, a common type of oxidative DNA damage. DNA strand breaks also increased in atherosclerotic plaques, thus linking DNA damage to plaque formation.

Werner syndrome (WS), a premature aging condition in humans, is caused by a genetic defect in a RecQ helicase that is employed in several DNA repair processes. WS patients develop a substantial burden of atherosclerotic plaques in their coronary arteries and aorta. These findings link excessive unrepaired DNA damage to premature aging and early atherosclerotic plaque development.

DNA damage and the epigenetic clock

Endogenous, naturally occurring DNA damages are frequent, and in humans include an average of about 10,000 oxidative damages per day and 50 double-strand DNA breaks per cell cycle.

Several reviews summarize evidence that the methylation enzyme DNMT1 is recruited to sites of oxidative DNA damage. Recruitment of DNMT1 leads to DNA methylation at the promoters of genes to inhibit transcription during repair. In addition, the 2018 review describes recruitment of DNMT1 during repair of DNA double-strand breaks. DNMT1 localization results in increased DNA methylation near the site of recombinational repair, associated with altered expression of the repaired gene. In general, repair-associated hyper-methylated promoters are restored to their former methylation level after DNA repair is complete. However, these reviews also indicate that transient recruitment of epigenetic modifiers can occasionally result in subsequent stable epigenetic alterations and gene silencing after DNA repair has been completed.

In human and mouse DNA, cytosine followed by guanine (CpG) is the least frequent dinucleotide, making up less than 1% of all dinucleotides (see CG suppression). At most CpG sites cytosine is methylated to form 5-methylcytosine. As indicated in the article CpG site, in mammals, 70% to 80% of CpG cytosines are methylated. However, in vertebrates there are CpG islands, about 300 to 3,000 base pairs long, with interspersed DNA sequences that deviate significantly from the average genomic pattern by being CpG-rich. These CpG islands are predominantly nonmethylated. In humans, about 70% of promoters located near the transcription start site of a gene (proximal promoters) contain a CpG island (see CpG islands in promoters). If the initially nonmethylated CpG sites in a CpG island become largely methylated, this causes stable silencing of the associated gene.

For humans, after adulthood is reached and during subsequent aging, the majority of CpG sequences slowly lose methylation (called epigenetic drift). However, the CpG islands that control promoters tend to gain methylation with age. The gain of methylation at CpG islands in promoter regions is correlated with age, and has been used to create an epigenetic clock.

There may be some relationship between the epigenetic clock and epigenetic alterations accumulating after DNA repair. Both unrepaired DNA damage accumulated with age and accumulated methylation of CpG islands would silence genes in which they occur, interfere with protein expression, and contribute to the aging phenotype.