Radiometric dating, radioactive dating or radioisotope dating is a technique which is used to date materials such as rocks or carbon, in which trace radioactive impurities were selectively incorporated when they were formed. The method compares the abundance of a naturally occurring radioactive isotope within the material to the abundance of its decay products, which form at a known constant rate of decay. The use of radiometric dating was first published in 1907 by Bertram Boltwood and is now the principal source of information about the absolute age of rocks and other geological features, including the age of fossilized life forms or the age of the Earth itself, and can also be used to date a wide range of natural and man-made materials.

Together with stratigraphic principles, radiometric dating methods are used in geochronology to establish the geologic time scale. Among the best-known techniques are radiocarbon dating, potassium–argon dating and uranium–lead dating. By allowing the establishment of geological timescales, it provides a significant source of information about the ages of fossils and the deduced rates of evolutionary change. Radiometric dating is also used to date archaeological materials, including ancient artifacts.

Different methods of radiometric dating vary in the timescale over which they are accurate and the materials to which they can be applied.

Fundamentals

Radioactive decay

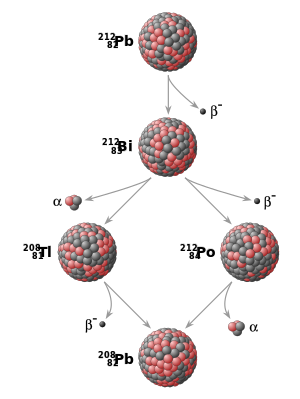

All ordinary matter is made up of combinations of chemical elements, each with its own atomic number, indicating the number of protons in the atomic nucleus. Additionally, elements may exist in different isotopes, with each isotope of an element differing in the number of neutrons in the nucleus. A particular isotope of a particular element is called a nuclide. Some nuclides are inherently unstable. That is, at some point in time, an atom of such a nuclide will undergo radioactive decay and spontaneously transform into a different nuclide. This transformation may be accomplished in a number of different ways, including alpha decay (emission of alpha particles) and beta decay (electron emission, positron emission, or electron capture). Another possibility is spontaneous fission into two or more nuclides.

While the moment in time at which a particular nucleus decays is unpredictable, a collection of atoms of a radioactive nuclide decays exponentially at a rate described by a parameter known as the half-life, usually given in units of years when discussing dating techniques. After one half-life has elapsed, one half of the atoms of the nuclide in question will have decayed into a "daughter" nuclide or decay product. In many cases, the daughter nuclide itself is radioactive, resulting in a decay chain, eventually ending with the formation of a stable (nonradioactive) daughter nuclide; each step in such a chain is characterized by a distinct half-life. In these cases, usually the half-life of interest in radiometric dating is the longest one in the chain, which is the rate-limiting factor in the ultimate transformation of the radioactive nuclide into its stable daughter. Isotopic systems that have been exploited for radiometric dating have half-lives ranging from only about 10 years (e.g., tritium) to over 100 billion years (e.g., samarium-147).

For most radioactive nuclides, the half-life depends solely on nuclear properties and is essentially constant. This is known because decay constants measured by different techniques give consistent values within analytical errors and the ages of the same materials are consistent from one method to another. It is not affected by external factors such as temperature, pressure, chemical environment, or presence of a magnetic or electric field. The only exceptions are nuclides that decay by the process of electron capture, such as beryllium-7, strontium-85, and zirconium-89, whose decay rate may be affected by local electron density. For all other nuclides, the proportion of the original nuclide to its decay products changes in a predictable way as the original nuclide decays over time.

This predictability allows the relative abundances of related nuclides to be used as a clock to measure the time from the incorporation of the original nuclides into a material to the present. Nature has conveniently provided us with radioactive nuclides that have half-lives which range from considerably longer than the age of the universe, to less than a zeptosecond. This allows one to measure a very wide range of ages. Isotopes with very long half-lives are called "stable isotopes," and isotopes with very short half-lives are known as "extinct isotopes."

Decay constant determination

The radioactive decay constant, the probability that an atom will decay per year, is the solid foundation of the common measurement of radioactivity. The accuracy and precision of the determination of an age (and a nuclide's half-life) depends on the accuracy and precision of the decay constant measurement. The in-growth method is one way of measuring the decay constant of a system, which involves accumulating daughter nuclides. Unfortunately for nuclides with high decay constants (which are useful for dating very old samples), long periods of time (decades) are required to accumulate enough decay products in a single sample to accurately measure them. A faster method involves using particle counters to determine alpha, beta or gamma activity, and then dividing that by the number of radioactive nuclides. However, it is challenging and expensive to accurately determine the number of radioactive nuclides. Alternatively, decay constants can be determined by comparing isotope data for rocks of known age. This method requires at least one of the isotope systems to be very precisely calibrated, such as the Pb-Pb system.

Accuracy of radiometric dating

The basic equation of radiometric dating requires that neither the parent nuclide nor the daughter product can enter or leave the material after its formation. The possible confounding effects of contamination of parent and daughter isotopes have to be considered, as do the effects of any loss or gain of such isotopes since the sample was created. It is therefore essential to have as much information as possible about the material being dated and to check for possible signs of alteration. Precision is enhanced if measurements are taken on multiple samples from different locations of the rock body. Alternatively, if several different minerals can be dated from the same sample and are assumed to be formed by the same event and were in equilibrium with the reservoir when they formed, they should form an isochron. This can reduce the problem of contamination. In uranium–lead dating, the concordia diagram is used which also decreases the problem of nuclide loss. Finally, correlation between different isotopic dating methods may be required to confirm the age of a sample. For example, the age of the Amitsoq gneisses from western Greenland was determined to be 3.60 ± 0.05 Ga (billion years ago) using uranium–lead dating and 3.56 ± 0.10 Ga (billion years ago) using lead–lead dating, results that are consistent with each other.

Accurate radiometric dating generally requires that the parent has a long enough half-life that it will be present in significant amounts at the time of measurement (except as described below under "Dating with short-lived extinct radionuclides"), the half-life of the parent is accurately known, and enough of the daughter product is produced to be accurately measured and distinguished from the initial amount of the daughter present in the material. The procedures used to isolate and analyze the parent and daughter nuclides must be precise and accurate. This normally involves isotope-ratio mass spectrometry.

The precision of a dating method depends in part on the half-life of the radioactive isotope involved. For instance, carbon-14 has a half-life of 5,730 years. After an organism has been dead for 60,000 years, so little carbon-14 is left that accurate dating cannot be established. On the other hand, the concentration of carbon-14 falls off so steeply that the age of relatively young remains can be determined precisely to within a few decades.

Closure temperature

The closure temperature or blocking temperature represents the temperature below which the mineral is a closed system for the studied isotopes. If a material that selectively rejects the daughter nuclide is heated above this temperature, any daughter nuclides that have been accumulated over time will be lost through diffusion, resetting the isotopic "clock" to zero. As the mineral cools, the crystal structure begins to form and diffusion of isotopes is less easy. At a certain temperature, the crystal structure has formed sufficiently to prevent diffusion of isotopes. Thus an igneous or metamorphic rock or melt, which is slowly cooling, does not begin to exhibit measurable radioactive decay until it cools below the closure temperature. The age that can be calculated by radiometric dating is thus the time at which the rock or mineral cooled to closure temperature. This temperature varies for every mineral and isotopic system, so a system can be closed for one mineral but open for another. Dating of different minerals and/or isotope systems (with differing closure temperatures) within the same rock can therefore enable the tracking of the thermal history of the rock in question with time, and thus the history of metamorphic events may become known in detail. These temperatures are experimentally determined in the lab by artificially resetting sample minerals using a high-temperature furnace. This field is known as thermochronology or thermochronometry.

The age equation

The mathematical expression that relates radioactive decay to geologic time is

where

- t is age of the sample,

- D* is number of atoms of the radiogenic daughter isotope in the sample,

- D0 is number of atoms of the daughter isotope in the original or initial composition,

- N(t) is number of atoms of the parent isotope in the sample at time t (the present), given by N(t) = N0e−λt, and

- λ is the decay constant of the parent isotope, equal to the inverse of the radioactive half-life of the parent isotope times the natural logarithm of 2.

The equation is most conveniently expressed in terms of the measured quantity N(t) rather than the constant initial value No.

To calculate the age, it is assumed that the system is closed (neither parent nor daughter isotopes have been lost from system), D0 must be either negligible or can be accurately estimated, λ is known to a high precision, and one has accurate and precise measurements of D* and N(t).

The above equation makes use of information on the composition of parent and daughter isotopes at the time the material being tested cooled below its closure temperature. This is well-established for most isotopic systems. However, construction of an isochron does not require information on the original compositions, using merely the present ratios of the parent and daughter isotopes to a standard isotope. An isochron plot is used to solve the age equation graphically and calculate the age of the sample and the original composition.

Modern dating methods

Radiometric dating has been carried out since 1905 when it was invented by Ernest Rutherford as a method by which one might determine the age of the Earth. In the century since then the techniques have been greatly improved and expanded. Dating can now be performed on samples as small as a nanogram using a mass spectrometer. The mass spectrometer was invented in the 1940s and began to be used in radiometric dating in the 1950s. It operates by generating a beam of ionized atoms from the sample under test. The ions then travel through a magnetic field, which diverts them into different sampling sensors, known as "Faraday cups", depending on their mass and level of ionization. On impact in the cups, the ions set up a very weak current that can be measured to determine the rate of impacts and the relative concentrations of different atoms in the beams.

Uranium–lead dating method

Uranium–lead radiometric dating involves using uranium-235 or uranium-238 to date a substance's absolute age. This scheme has been refined to the point that the error margin in dates of rocks can be as low as less than two million years in two-and-a-half billion years. An error margin of 2–5% has been achieved on younger Mesozoic rocks.

Uranium–lead dating is often performed on the mineral zircon (ZrSiO4), though it can be used on other materials, such as baddeleyite and monazite (see: monazite geochronology). Zircon and baddeleyite incorporate uranium atoms into their crystalline structure as substitutes for zirconium, but strongly reject lead. Zircon has a very high closure temperature, is resistant to mechanical weathering and is very chemically inert. Zircon also forms multiple crystal layers during metamorphic events, which each may record an isotopic age of the event. In situ micro-beam analysis can be achieved via laser ICP-MS or SIMS techniques.

One of its great advantages is that any sample provides two clocks, one based on uranium-235's decay to lead-207 with a half-life of about 700 million years, and one based on uranium-238's decay to lead-206 with a half-life of about 4.5 billion years, providing a built-in crosscheck that allows accurate determination of the age of the sample even if some of the lead has been lost. This can be seen in the concordia diagram, where the samples plot along an errorchron (straight line) which intersects the concordia curve at the age of the sample.

Samarium–neodymium dating method

This involves the alpha decay of 147Sm to 143Nd with a half-life of 1.06 x 1011 years. Accuracy levels of within twenty million years in ages of two-and-a-half billion years are achievable.

Potassium–argon dating method

This involves electron capture or positron decay of potassium-40 to argon-40. Potassium-40 has a half-life of 1.3 billion years, so this method is applicable to the oldest rocks. Radioactive potassium-40 is common in micas, feldspars, and hornblendes, though the closure temperature is fairly low in these materials, about 350 °C (mica) to 500 °C (hornblende).

Rubidium–strontium dating method

This is based on the beta decay of rubidium-87 to strontium-87, with a half-life of 50 billion years. This scheme is used to date old igneous and metamorphic rocks, and has also been used to date lunar samples. Closure temperatures are so high that they are not a concern. Rubidium-strontium dating is not as precise as the uranium-lead method, with errors of 30 to 50 million years for a 3-billion-year-old sample. Application of in situ analysis (Laser-Ablation ICP-MS) within single mineral grains in faults have shown that the Rb-Sr method can be used to decipher episodes of fault movement.

Uranium–thorium dating method

A relatively short-range dating technique is based on the decay of uranium-234 into thorium-230, a substance with a half-life of about 80,000 years. It is accompanied by a sister process, in which uranium-235 decays into protactinium-231, which has a half-life of 32,760 years.

While uranium is water-soluble, thorium and protactinium are not, and so they are selectively precipitated into ocean-floor sediments, from which their ratios are measured. The scheme has a range of several hundred thousand years. A related method is ionium–thorium dating, which measures the ratio of ionium (thorium-230) to thorium-232 in ocean sediment.

Radiocarbon dating method

Radiocarbon dating is also simply called carbon-14 dating. Carbon-14 is a radioactive isotope of carbon, with a half-life of 5,730 years (which is very short compared with the above isotopes), and decays into nitrogen. In other radiometric dating methods, the heavy parent isotopes were produced by nucleosynthesis in supernovas, meaning that any parent isotope with a short half-life should be extinct by now. Carbon-14, though, is continuously created through collisions of neutrons generated by cosmic rays with nitrogen in the upper atmosphere and thus remains at a near-constant level on Earth. The carbon-14 ends up as a trace component in atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2).

A carbon-based life form acquires carbon during its lifetime. Plants acquire it through photosynthesis, and animals acquire it from consumption of plants and other animals. When an organism dies, it ceases to take in new carbon-14, and the existing isotope decays with a characteristic half-life (5730 years). The proportion of carbon-14 left when the remains of the organism are examined provides an indication of the time elapsed since its death. This makes carbon-14 an ideal dating method to date the age of bones or the remains of an organism. The carbon-14 dating limit lies around 58,000 to 62,000 years.

The rate of creation of carbon-14 appears to be roughly constant, as cross-checks of carbon-14 dating with other dating methods show it gives consistent results. However, local eruptions of volcanoes or other events that give off large amounts of carbon dioxide can reduce local concentrations of carbon-14 and give inaccurate dates. The releases of carbon dioxide into the biosphere as a consequence of industrialization have also depressed the proportion of carbon-14 by a few percent; conversely, the amount of carbon-14 was increased by above-ground nuclear bomb tests that were conducted into the early 1960s. Also, an increase in the solar wind or the Earth's magnetic field above the current value would depress the amount of carbon-14 created in the atmosphere.

Fission track dating method

This involves inspection of a polished slice of a material to determine the density of "track" markings left in it by the spontaneous fission of uranium-238 impurities. The uranium content of the sample has to be known, but that can be determined by placing a plastic film over the polished slice of the material, and bombarding it with slow neutrons. This causes induced fission of 235U, as opposed to the spontaneous fission of 238U. The fission tracks produced by this process are recorded in the plastic film. The uranium content of the material can then be calculated from the number of tracks and the neutron flux.

This scheme has application over a wide range of geologic dates. For dates up to a few million years micas, tektites (glass fragments from volcanic eruptions), and meteorites are best used. Older materials can be dated using zircon, apatite, titanite, epidote and garnet which have a variable amount of uranium content. Because the fission tracks are healed by temperatures over about 200 °C the technique has limitations as well as benefits. The technique has potential applications for detailing the thermal history of a deposit.

Chlorine-36 dating method

Large amounts of otherwise rare 36Cl (half-life ~300ky) were produced by irradiation of seawater during atmospheric detonations of nuclear weapons between 1952 and 1958. The residence time of 36Cl in the atmosphere is about 1 week. Thus, as an event marker of 1950s water in soil and ground water, 36Cl is also useful for dating waters less than 50 years before the present. 36Cl has seen use in other areas of the geological sciences, including dating ice and sediments.

Luminescence dating methods

Luminescence dating methods are not radiometric dating methods in that they do not rely on abundances of isotopes to calculate age. Instead, they are a consequence of background radiation on certain minerals. Over time, ionizing radiation is absorbed by mineral grains in sediments and archaeological materials such as quartz and potassium feldspar. The radiation causes charge to remain within the grains in structurally unstable "electron traps". Exposure to sunlight or heat releases these charges, effectively "bleaching" the sample and resetting the clock to zero. The trapped charge accumulates over time at a rate determined by the amount of background radiation at the location where the sample was buried. Stimulating these mineral grains using either light (optically stimulated luminescence or infrared stimulated luminescence dating) or heat (thermoluminescence dating) causes a luminescence signal to be emitted as the stored unstable electron energy is released, the intensity of which varies depending on the amount of radiation absorbed during burial and specific properties of the mineral.

These methods can be used to date the age of a sediment layer, as layers deposited on top would prevent the grains from being "bleached" and reset by sunlight. Pottery shards can be dated to the last time they experienced significant heat, generally when they were fired in a kiln.

Other methods

Other methods include:

- Argon–argon (Ar–Ar)

- Iodine–xenon (I–Xe)

- Lanthanum–barium (La–Ba)

- Lead–lead (Pb–Pb)

- Lutetium–hafnium (Lu–Hf)

- Hafnium–tungsten dating (Hf-W)

- Potassium–calcium (K–Ca)

- Rhenium–osmium (Re–Os)

- Uranium–uranium (U–U)

- Krypton–krypton (Kr–Kr)

- Beryllium (10Be–9Be)

Dating with decay products of short-lived extinct radionuclides

Absolute radiometric dating requires a measurable fraction of parent nucleus to remain in the sample rock. For rocks dating back to the beginning of the solar system, this requires extremely long-lived parent isotopes, making measurement of such rocks' exact ages imprecise. To be able to distinguish the relative ages of rocks from such old material, and to get a better time resolution than that available from long-lived isotopes, short-lived isotopes that are no longer present in the rock can be used.

At the beginning of the solar system, there were several relatively short-lived radionuclides like 26Al, 60Fe, 53Mn, and 129I present within the solar nebula. These radionuclides—possibly produced by the explosion of a supernova—are extinct today, but their decay products can be detected in very old material, such as that which constitutes meteorites. By measuring the decay products of extinct radionuclides with a mass spectrometer and using isochronplots, it is possible to determine relative ages of different events in the early history of the solar system. Dating methods based on extinct radionuclides can also be calibrated with the U-Pb method to give absolute ages. Thus both the approximate age and a high time resolution can be obtained. Generally a shorter half-life leads to a higher time resolution at the expense of timescale.

The 129I – 129Xe chronometer

129

I

beta-decays to 129

Xe

with a half-life of 16 million years. The iodine-xenon chronometer

is an isochron technique. Samples are exposed to neutrons in a nuclear

reactor. This converts the only stable isotope of iodine (127

I

) into 128

Xe

via neutron capture followed by beta decay (of 128

I

). After irradiation, samples are heated in a series of steps and the xenon isotopic signature of the gas evolved in each step is analysed. When a consistent 129

Xe

/128

Xe

ratio is observed across several consecutive temperature steps, it can

be interpreted as corresponding to a time at which the sample stopped

losing xenon.

Samples of a meteorite called Shallowater are usually included in the irradiation to monitor the conversion efficiency from 127

I

to 128

Xe

. The difference between the measured 129

Xe

/128

Xe

ratios of the sample and Shallowater then corresponds to the different ratios of 129

I

/127

I

when they each stopped losing xenon. This in turn corresponds to a difference in age of closure in the early solar system.

The 26Al – 26Mg chronometer

Another example of short-lived extinct radionuclide dating is the 26

Al

– 26

Mg

chronometer, which can be used to estimate the relative ages of chondrules. 26

Al

decays to 26

Mg

with a half-life of 720 000 years. The dating is simply a question of finding the deviation from the natural abundance of 26

Mg

(the product of 26

Al

decay) in comparison with the ratio of the stable isotopes 27

Al

/24

Mg

.

The excess of 26

Mg

(often designated 26

Mg

*) is found by comparing the 26

Mg

/27

Mg

ratio to that of other Solar System materials.

The 26

Al

– 26

Mg

chronometer gives an estimate of the time period for formation of

primitive meteorites of only a few million years (1.4 million years for

Chondrule formation).