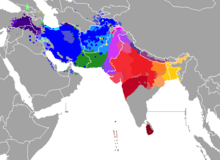

Indo-Iranian peoples, also known as Indo-Iranic peoples by scholars, and sometimes as Arya or Aryans from their self-designation, were a group of Indo-European peoples who brought the Indo-Iranian languages, a major branch of the Indo-European language family, to major parts of Eurasia in the second part of the 3rd millennium BCE. They eventually branched out into Iranian peoples and Indo-Aryan peoples, predominantly in the geographical subregion of Southern Asia.

Nomenclature

The term Aryan has long been used to denote the Indo-Iranians, because Arya is indeed the self-designation of the ancient speakers of the Indo-Iranian languages, specifically the Iranian and the Indo-Aryan peoples, collectively known as the Indo-Iranians. Despite this, some scholars use the term Indo-Iranian to refer to this group, though the term "Aryan" remains widely used by most scholars, such as Josef Wiesehofer, Will Durant, and Jaakko Häkkinen. Population geneticist Luigi Luca Cavalli-Sforza, in his 1994 book The History and Geography of Human Genes, also uses the term Aryan to describe the Indo-Iranians.

History

Origin

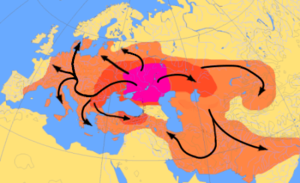

The early Indo-Iranians are commonly identified with the descendants of the Proto-Indo-Europeans known as the Sintashta culture and the subsequent Andronovo culture within the broader Andronovo horizon, and their homeland with an area of the Eurasian steppe that borders the Ural River on the west, the Tian Shan on the east (where the Indo-Iranians took over the area occupied by the earlier Afanasevo culture), and Transoxiana and the Hindu Kush on the south.

Based on its use by Indo-Aryans in Mitanni and Vedic India, its prior absence in the Near East and Harappan India, and its 19th–20th century BCE attestation at the Andronovo site of Sintashta, Kuzmina (1994) argues that the chariot corroborates the identification of Andronovo as Indo-Iranian. Anthony & Vinogradov (1995) dated a chariot burial at Krivoye Lake to about 2000 BCE, and a Bactria-Margiana burial that also contains a foal has recently been found, indicating further links with the steppes.

Historical linguists broadly estimate that a continuum of Indo-Iranian languages probably began to diverge by 2000 BCE, if not earlier, preceding both the Vedic and Iranian cultures. The earliest recorded forms of these languages, Vedic Sanskrit and Gathic Avestan, are remarkably similar, descended from the common Proto-Indo-Iranian language. The origin and earliest relationship between the Nuristani languages and that of the Iranian and Indo-Aryan groups is not completely clear.

Expansion

First wave – Indo-Aryans

Two-wave models of Indo-Iranian expansion have been proposed by Burrow (1973) and Parpola (1999). The Indo-Iranians and their expansion are strongly associated with the Proto-Indo-European invention of the chariot. It is assumed that this expansion spread from the Proto-Indo-European homeland north of the Caspian sea south to the Caucasus, Central Asia, the Iranian plateau, and the Indian subcontinent.

The Mitanni of Anatolia

The Mitanni, a people known in eastern Anatolia from about 1500 BCE, were of possibly of mixed origins: a Hurrian-speaking majority was supposedly dominated by a non-Anatolian, Indo-Aryan elite. There is linguistic evidence for such a superstrate, in the form of:

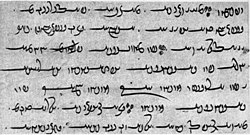

- a horse training manual written by a Mitanni man named Kikkuli, which was used by the Hittites, an Indo-European Anatolian people;

- the names of Mitanni rulers and;

- the names of gods invoked by these rulers in treaties.

In particular, Kikkuli's text includes words such as aika "one" (i.e. a cognate of the Indo-Aryan eka), tera "three" (tri), panza "five" (pancha), satta "seven", (sapta), na "nine" (nava), and vartana "turn around", in the context of a horse race (Indo-Aryan vartana). In a treaty between the Hittites and the Mitanni, the Ashvin deities Mitra, Varuna, Indra, and Nasatya are invoked. These loanwords tend to connect the Mitanni superstrate to Indo-Aryan rather than Iranian languages – i.e. the early Iranian word for "one" was aiva.

Indian subcontinent – Vedic culture

The standard model for the entry of the Indo-European languages into the Indian subcontinent is that this first wave went over the Hindu Kush, either into the headwaters of the Indus and later the Ganges. The earliest stratum of Vedic Sanskrit, preserved only in the Rigveda, is assigned to roughly 1500 BCE. From the Indus, the Indo-Aryan languages spread from c. 1500 BCE to c. 500 BCE, over the northern and central parts of the subcontinent, sparing the extreme south. The Indo-Aryans in these areas established several powerful kingdoms and principalities in the region, from south eastern Afghanistan to the doorstep of Bengal. The most powerful of these kingdoms were the post-Rigvedic Kuru (in Kurukshetra and the Delhi area) and their allies the Pañcālas further east, as well as Gandhara and later on, about the time of the Buddha, the kingdom of Kosala and the quickly expanding realm of Magadha. The latter lasted until the 4th century BCE, when it was conquered by Chandragupta Maurya and formed the center of the Mauryan empire.

In eastern Afghanistan and some western regions of Pakistan, Indo-Aryan languages were eventually replaced by Eastern Iranian languages. Most Indo-Aryan languages, however, were and still are prominent in the rest of the Indian subcontinent. Today, Indo-Aryan languages are spoken in India, Pakistan, Bangladesh, Nepal, Sri Lanka, Fiji, Suriname and the Maldives.

Second wave – Iranians

The second wave is interpreted as the Iranian wave. The first Iranians to reach the Black Sea may have been the Cimmerians in the 8th century BCE, although their linguistic affiliation is uncertain. They were followed by the Scythians, who are considered a western branch of the Central Asian Sakas. Sarmatian tribes, of whom the best known are the Roxolani (Rhoxolani), Iazyges (Jazyges) and the Alani (Alans), followed the Scythians westwards into Europe in the late centuries BCE and the 1st and 2nd centuries CE (The Age of Migrations). The populous Sarmatian tribe of the Massagetae, dwelling near the Caspian Sea, were known to the early rulers of Persia in the Achaemenid Period. At their greatest reported extent, around 1st century CE, the Sarmatian tribes ranged from the Vistula River to the mouth of the Danube and eastward to the Volga, bordering the shores of the Black and Caspian seas as well as the Caucasus to the south.[note 2] In the east, the Saka occupied several areas in Xinjiang, from Khotan to Tumshuq.

The Medians, Persians and Parthians begin to appear on the Iranian plateau from c. 800 BCE, and the Achaemenids replaced Elamite rule from 559 BCE. Around the first millennium CE, Iranian groups began to settle on the eastern edge of the Iranian plateau, on the mountainous frontier of northwestern and western Pakistan, displacing the earlier Indo-Aryans from the area.

In Eastern Europe, the Iranians were eventually decisively assimilated (e.g. Slavicisation) and absorbed by the Proto-Slavic population of the region, while in Central Asia, the Turkic languages marginalized the Iranian languages as a result of the Turkic expansion of the early centuries CE. Extant major Iranian languages are Persian, Pashto, Kurdish, and Balochi besides numerous smaller ones. Ossetian, primarily spoken in North Ossetia and South Ossetia, is a direct descendant of Alanic, and by that the only surviving Sarmatian language of the once wide-ranging East Iranian dialect continuum that stretched from Eastern Europe to the eastern parts of Central Asia.

Archaeology

Archaeological cultures associated with Indo-Iranian expansion include:

- Europe

- Poltavka culture (2500–2100 BCE)

- Abashevo culture (2300–1850 BCE)

- Srubna culture (1850–1450 BCE)

- Central Asia

- Andronovo horizon (2000–1450 BCE)

- Sintashta-Petrovka-Arkaim (2050–1750 BCE)

- Alakul (2100–1400 BCE)

- Fedorovo (1400–1200 BCE)

- Alekseyevka (1200–1000 BCE)

- Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (2200–1700 BCE)

- Yaz culture (1500–1100 BCE)

- Andronovo horizon (2000–1450 BCE)

- Indian subcontinent

- Ochre Coloured Pottery culture (2000–1500 BCE)

- Cemetery H culture (1900–1300 BCE)

- Swat culture (1400–800 BCE)

- Painted Gray Ware culture (1200–600 BCE)

- Iranian Plateau

- Early West Iranian Grey Ware (1500–1000 BCE)

- Late West Iranian Buff Ware (900–700 BCE)

Parpola (1999) suggests the following identifications:

| Date range | Archaeological culture | Identification suggested by Parpola |

|---|---|---|

| 2800–2000 BCE | late Catacomb and Poltavka cultures | late PIE to Proto–Indo-Iranian |

| 2000–1800 BCE | Srubna and Abashevo cultures | Proto-Iranian |

| 2000–1800 BCE | Petrovka-Sintashta | Proto–Indo-Aryan |

| 1900–1700 BCE | BMAC | "Proto-Dasa" Indo-Aryans establishing themselves in the existing BMAC settlements, defeated by "Proto-Rigvedic" Indo-Aryans around 1700 |

| 1900–1400 BCE | Cemetery H | Indian Dasa |

| 1800–1000 BCE | Alakul-Fedorovo | Indo-Aryan, including "Proto–Sauma-Aryan" practicing the Soma cult |

| 1700–1400 BCE | early Swat culture | Proto-Rigvedic |

| 1700–1500 BCE | late BMAC | "Proto–Sauma-Dasa", assimilation of Proto-Dasa and Proto–Sauma-Aryan |

| 1500–1000 BCE | Early West Iranian Grey Ware | Mitanni-Aryan (offshoot of "Proto–Sauma-Dasa") |

| 1400–800 BCE | late Swat culture and Punjab, Painted Grey Ware | late Rigvedic |

| 1400–1100 BCE | Yaz II-III, Seistan | Proto-Avestan |

| 1100–1000 BCE | Gurgan Buff Ware, Late West Iranian Buff Ware | Proto-Persian, Proto-Median |

| 1000–400 BCE | Iron Age cultures of Xinjiang | Proto-Saka |

Language

The Indo-European language spoken by the Indo-Iranians in the late 3rd millennium BCE was a Satem language still not removed very far from the Proto-Indo-European language, and in turn only removed by a few centuries from Vedic Sanskrit of the Rigveda. The main phonological change separating Proto-Indo-Iranian from Proto–Indo-European is the collapse of the ablauting vowels *e, *o, *a into a single vowel, Proto–Indo-Iranian *a (but see Brugmann's law). Grassmann's law and Bartholomae's law were also complete in Proto-Indo-Iranian, as well as the loss of the labiovelars (kw, etc.) to k, and the Eastern Indo-European (Satem) shift from palatized k' to ć, as in Proto–Indo-European *k'ṃto- > Indo-Iran. *ćata- > Sanskrit śata-, Old Iran. sata "100".

Among the sound changes from Proto-Indo-Iranian to Indo-Aryan is the loss of the voiced sibilant *z, among those to Iranian is the de-aspiration of the PIE voiced aspirates.

Religion

Despite the introduction of later Vedic and Zoroastrian scriptures, Indo-Iranians shared a common inheritance of concepts including the universal force *Hṛta- (Sanskrit rta, Avestan asha), the sacred plant and drink *sawHma- (Sanskrit Soma, Avestan Haoma) and gods of social order such as *mitra- (Sanskrit Mitra, Avestan and Old Persian Mithra, Miθra) and *bʰaga- (Sanskrit Bhaga, Avestan and Old Persian Baga). Proto-Indo-Iranian religion is an archaic offshoot of Indo-European religion. From the various and dispersed Indo-Iranian cultures, a set of common ideas may be reconstructed from which a common, unattested proto-Indo-Iranian source may be deduced.

The pre-Islamic religion of the Nuristani people and extant religion of the Kalash people, is mostly based on the original religion of the Indo-Iranians. MIchael Witzel theorises that these religions might share some elements with Shinto, one of the national religions of Japan, which according to him may contain some Indo-Iranian influence owing to contact presumably in the steppes of Central Asia at around 2000 BCE. In Shinto, traces of these can be seen in the myth of the storm god Susanoo slaying a serpent Yamata-no-Orochi and in the myth of the dawn goddess Ame-no-Uzume.

Development

Beliefs developed in different ways as cultures separated and evolved. For example, the cosmo-mythology of the peoples that remained on the Central Asian steppes and the Iranian plateau is to a great degree unlike that of the Indians, focused more on groups of deities (*daiva and *asura) and less on the divinities individually. Indians were less conservative than Iranians in their treatment of their divinities, so that some deities were conflated with others or, conversely, aspects of a single divinity developed into divinities in their own right. By the time of Zoroaster, Iranian culture had also been subject to the upheavals of the Iranian Heroic Age (late Iranian Bronze Age, 1800–800 BCE), an influence that the Indo-Aryans were not subject to.

Sometimes certain myths developed in altogether different ways. The Rig-Vedic Sarasvati is linguistically and functionally cognate with Avestan *Haraxvaitī Ārəduuī Sūrā Anāhitā. In the Rig-Veda (6,61,5–7) she battles a serpent called Vritra, who has hoarded all of the Earth's water. In contrast, in early portions of the Avesta, Iranian *Harahvati is the world-river that flows down from the mythical central Mount Hara. But *Harahvati does no battle — she is blocked by an obstacle (Avestan for obstacle: vərəθra) placed there by Angra Mainyu.

Cognate terms

The following is a list of cognate terms that may be gleaned from comparative linguistic analysis of the Rigveda and Avesta. Both collections are from the period after the proposed date of separation (c. 2nd millennium BCE) of the Proto-Indo-Iranians into their respective Indic and Iranian branches.

| Vedic Sanskrit | Avestan | Common meaning |

|---|---|---|

| āp | āp | "water," āpas "the Waters" |

| Apam Napat, Apām Napāt | Apām Napāt | the "water's offspring" |

| aryaman | airyaman | "Arya-hood" (lit:** "member of Arya community") |

| Asura Mahata/Medha (असुर महत/मेधा) | Ahura Mazda | "The Supreme Lord, Lord of Wisdom" |

| rta | asha/arta | "active truth", extending to "order" & "righteousness" |

| atharvan | āθrauuan, aθaurun Atar | "priest" |

| ahi | azhi, (aži) | "dragon, snake", "serpent" |

| daiva, deva | daeva, (daēuua) | a class of divinities |

| manu | manu | "man" |

| mitra | mithra, miθra | "oath, covenant" |

| asura | ahura | another class of spirits |

| sarvatat | Hauruuatāt | "intactness", "perfection" |

| Sarasvatī (Ārdrāvī śūrā anāhitā, आर्द्रावी शूरा अनाहिता) | Haraxvaitī (Ārəduuī Sūrā Anāhitā) | a controversial (generally considered mythological) river, a river goddess |

| sauma, soma | haoma | a plant, deified |

| svar | hvar, xvar | the Sun, also cognate to Greek helios, Latin sol, Engl. Sun |

| Tapati | tapaiti | Possible fire/solar goddess; see Tabiti (a possibly Hellenised Scythian theonym). Cognate with Latin tepeo and several other terms. |

| Vrtra-/Vr̥tragʰná/Vritraban | verethra, vərəθra (cf. Verethragna, Vərəθraγna) | "obstacle" |

| Yama | Yima | son of the solar deity Vivasvant/Vīuuahuuant |

| yajña | yasna, object: yazata | "worship, sacrifice, oblation" |

| Gandharva | Gandarewa | "heavenly beings" |

| Nasatya | Nanghaithya | "twin Vedic gods associated with the dawn, medicine, and sciences" |

| Amarattya | Ameretat | "immortality" |

| Póṣa | Apaosha | "demon of drought" |

| Ashman | Asman | "sky, highest heaven" |

| Angira Manyu | Angra Mainyu | "destructive/evil spirit, spirit, temper, ardour, passion, anger, teacher of divine knowledge" |

| Manyu | Maniyu | "anger, wrath" |

| Sarva | Sarva | "Rudra, Vedic god of wind, Shiva" |

| Madhu | Madu | "honey" |

| Bhuta | Buiti | "ghost" |

| Mantra | Manthra | "sacred spell" |

| Aramati | Armaiti | "piety" |

| Amrita | Amesha | "nectar of immortality" |

| Amrita Spanda (अमृत स्पन्द) | Amesha Spenta | "holy nectar of immortality" |

| Sumati | Humata | "good thought" |

| Sukta | Hukhta | "good word" |

| Narasamsa | Nairyosangha | "praised man" |

| Vayu | Vaiiu | "wind" |

| Vajra | Vazra | "bolt" |

| Ushas | Ushah | "dawn" |

| Ahuti | azuiti | "offering" |

| púraṁdhi | purendi |

|

| bhaga | baga | "lord, patron, wealth, prosperity, sharer/distributor of good fortune" |

| Usij | Usij | "priest" |

| trita | thrita | "the third" |

| Mas | Mah | "moon, month" |

| Vivasvant | Vivanhvant | "lighting up, matutinal" |

| Druh | Druj | "Evil spirit" |

| Ahi Dasaka | Azhi Dahaka | "biting serpent" |

Genetics

R1a1a (R-M17 or R-M198) is the sub-clade most commonly associated with Indo-European speakers. Most discussions purportedly of R1a origins are actually about the origins of the dominant R1a1a (R-M17 or R-M198) sub-clade. Data so far collected indicates that there are two widely separated areas of high frequency, one in the northern Indian subcontinent, and the other in Eastern Europe, around Poland and Ukraine. The historical and prehistoric possible reasons for this are the subject of on-going discussion and attention amongst population geneticists and genetic genealogists, and are considered to be of potential interest to linguists and archaeologists also.

Out of 10 human male remains assigned to the Andronovo horizon from the Krasnoyarsk region, 9 possessed the R1a Y-chromosome haplogroup and one C-M130 haplogroup (xC3). mtDNA haplogroups of nine individuals assigned to the same Andronovo horizon and region were as follows: U4 (2 individuals), U2e, U5a1, Z, T1, T4, H, and K2b.

A 2004 study also established that during the Bronze Age/Iron Age period, the majority of the population of Kazakhstan (part of the Andronovo culture during the Bronze Age), was of west Eurasian origin (with mtDNA haplogroups such as U, H, HV, T, I and W), and that prior to the 13th–7th century BCE, all Kazakh samples belonged to European lineages.