Samson Agonistes (from Greek Σαμσών ἀγωνιστής, "Samson the champion") is a tragic closet drama by John Milton. It appeared with the publication of Milton's Paradise Regained in 1671, as the title page of that volume states: "Paradise Regained / A Poem / In IV Books / To Which Is Added / Samson Agonistes". It is generally thought that Samson Agonistes was begun around the same time as Paradise Regained but was completed after the larger work, possibly very close to the date of publishing, but there is no certainty.

Background

Milton began plotting various subjects for tragedies in a notebook created in the 1640s. Many of the ideas dealt with the topic of Samson, and he gave them titles such as Samson pursophorus or Hybristes ("Samson the Firebrand, or Samson the Violent"), Samson marriing or in Ramath Lechi, and Dagonalia (the unholy rites at which Samson performed his vindication of God). The title he chose emphasises Samson as a warrior or an athlete, and the play was included with Paradise Regained and printed on 29 May 1671 by John Starkey. It is uncertain as to when the work was composed, which leaves the possibility that it was an early work that was filled with Milton's ideas about the English Civil War or it was a later work that incorporates his despair over the Restoration. Evidence for the early dating is based on his early works and his belief in revolution whereas evidence for a later dating connects the play with his later works, such as Paradise Lost, and comments reflecting on the fall of the Commonwealth. In 1671, the work was printed with a new title page and prefaced his work with a discussion on Greek tragedy and Aristotle's Poetics.

On the title page, Milton wrote that the piece was a "Dramatic Poem" rather than a drama. He did not wish for it to be performed on stage, but thought that the text could still influence people. He hoped that by giving Samson attributes of other Biblical figures, including Job or the Psalmist, he could create a complex hero who would embody and help resolve theological issues. In writing the poem and choosing the character of Samson as his hero, Milton was also illustrating his own blindness, which afflicted him in his later life.

Play

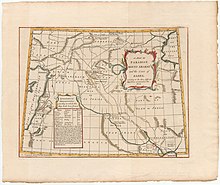

Samson Agonistes draws on the story of Samson from the Old Testament, Judges 13–16; in fact it is a dramatisation of the story starting at Judges 16:23. The drama starts in medias res. Samson has been captured by the Philistines, had his hair, the container of his strength, cut off and his eyes cut out. Samson is "Blind among enemies, O worse than chains" (line 66).

Near the beginning of the play, Samson humbles himself before God by admitting that his power is not his own: "God, when he gave me strength, to show withal / How slight the gift was, hung it in my hair" (lines 58–9).

The Chorus discusses Samson's background and describes his various military accomplishments:

- Ran on embattled armies clad in iron,

- And, weaponless himself,

- Made arms ridiculous, useless the forgery

- Of brazen shield and spear, the hammered cuirass,

- Chalybean-tempered steel, and frock of mail

- Adamantean proof;

- ...

- Then with what trivial weapon came to hand,

- The jaw of a dead ass, his sword of bone,

- A thousand foreskins fell

- (lines 129–134, 142–4)

Although he is great, the Chorus points out that, through his blindness (actual and metaphorically), he is a prisoner:

- Thou art become (O worst imprisonment!)

- The Dungeon of thy self; thy soul

- (Which men enjoying sight oft without cause complain)

- Imprisoned now indeed,

- In real darkness of the body dwells,

- Shut up from outward light

- To incorporate with gloomy night

- For inward light alas

- Puts forth no visual beam

- (lines 155–163)

Samson reveals how he lost his power because of his desire for Dalila, and, through this act, betrayed God:

I yielded, and unlocked her all my heart,

Who with a grain of manhood well resolved

Might easily have shook off all her snares:

But foul effeminancy held me yoked

Her bond-slave. O indignity, O blot

To honor and religion! Servile mind

Rewarded well with servile punishment!

(lines 407–413)

However, his state is more than just his own, and it represents a metaphor for the suffering of God's chosen people when Samson says:

- Or to th' unjust tribunals, under change of times,

- And condemnation of the ingrateful multitude.

- If these they scape, perhaps in poverty

- With sickness and disease thou bow'st them down,

- (lines 695–698)

After Samson rejects Dalila's pleas, she asks for Samson to "let me approach at least, and touch thy hand" (line 951), and Samson responds, "Not for thy life, lest fierce remembrance wake / My sudden rage to tear thee joint by joint" (lines 952–3). He shows Dalila how not to upset him: “At distance I forgive thee, go with that" (line 954). The Chorus, shortly after, complains about the nature of women and how deceptive they are:

- Whate'er it be, to wisest men and best

- Seeming at first all heavenly under virgin veil,

- Soft, modest, meek, demure,

- Once joined, the contrary she proves, a thorn

- Intestine, far within defensive arms

- A cleaving mischief, in his way to virtue

- Adverse and turbulent, or by her charms

- Draws him awry enslaved

- With dotage, and his sense depraved

- To folly and shameful deeds which ruin ends.

- (lines 1034–1043)

Harapha points out that Samson is

- ... no worthy match

- For valor to assail, nor by the sword

- Of noble warrior ...

- But by the barber’s razor best subdued

- (lines 1164-7)

But he does describe Samson's past accomplishments when he says "thou art famed / To have wrought such wonders with an ass’s jaw" (lines 1094–5).

The Chorus discusses how God grants individuals with the power to free his people from their bonds, especially through violent means:

- He all their ammunition

- And feats of war defeats

- With plain heroic magnitude of mind

- And celestial vigor armed;

- Their armouries and magazines contemns,

- Renders them useless, while

- With winged expedition

- Swift as the lightning glance he executes

- His errand on the wicked, who surprised

- Lose their defence, distracted and amazed.

- (lines 1277–86)

The last two hundred and fifty lines describe the violent act that actually occurs while the play was unfolding: Samson is granted the power to destroy the temple and kill all of the Philistines along with himself. However, this event does not take place on stage but is told through others. When the temple's destruction is reported, there is an emphasis on death and not peace:

- Man. I know your friendly minds and – O what noise!

- Mercy of Heav’n, what hideous noise was that!

- Horribly loud, unlike the former shout.

- Chor. Noise call you it, or universal groan,

- As if the whole inhabitation perished?

- Blood, death, and dreadful deeds are in that noise,

- Ruin, destruction at the utmost point.

- Man. Of ruin indeed methought I heard the noise.

- Oh it continues, they have slain my son.

- Chor. Thy son is rather slaying them; that outcry

- From slaughter of one foe could not ascend.

- Man. Some dismal accident it needs must be;

- What shall we do, stay here or run and see?

- Chor. Best keep together here, lest running thither

- We unawares run into danger’s mouth.

- This evil on the Philistines is fall’n;

- From whom could else a general cry be heard?

- (lines 1508–24)

Manoah describes the event as "Sad, but thou know’st to Israelites not saddest / The desolation of a hostile city" (lines 1560–1)

The final lines describe a catharsis that seems to take over at the end of the play:

- His servants he with new acquist

- Of true experience from this great event

- With peace and consolation hath dismissed,

- And calm of mind, all passion spent.

- (lines 1755–1758)

Cast

The Persons

- Samson

- Manoa the Father of Samson

- Dalila his Wife

- Harapha of Gath

- Public Officer

- Messenger

- Chorus of Danites

Themes

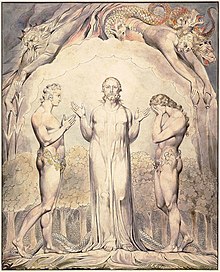

Samson Agonistes combines Greek tragedy with Hebrew Scripture, which alters both forms. Milton believed that the Bible was better in its classical forms than those written by the Greeks and Romans. In his introduction, Milton discusses Aristotle's definition of tragedy and sets out his own paraphrase of it to connect it to Samson Agonistes:

Tragedy, as it was anciently composed, hath been ever held the gravest, moralest, and most profitable of all other poems: therefore said by Aristotle to be of power by raising pity and fear, or terror, to purge the mind of those and such-like passions, that is to temper and reduce them to just measure with a kind of delight, stirred up by reading or seeing those passions well imitated. Nor is nature wanting in her own effects to make good his assertion: for so in physic things of melancholic hue and quality are used against melancholy, sour against sour, salt to remove salt humors.

Milton continues, "Of the style and uniformity, and that commonly called the plot, whether intricate or explicit... they only will best judge who are not unacquainted with Aeschylus, Sophocles, and Euripides, the three tragic poets unequaled yet by any, and the best rule to all who endeavor to write tragedy".

The reliance on Hebrew Scripture allows Milton to emphasise a plot that he feels is worthy of discussion, while the elements of Greek tragedy allows Milton to deal with complex issues through use of choruses and messengers instead of directly depicting them in addition to softening the Hebrew characters. This merging of two forms alters Samson from a rough barbarian into a pious warrior of God.

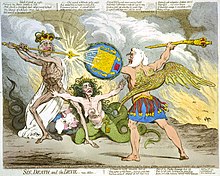

Violence

Acts of violence are an important theme within Samson Agonistes as the play attempts to deal with revenge and the destruction of God's enemies. Michael Lieb posits that "the drama is a work of violence to its very core. It extols violence. Indeed, it exults in violence". John Coffey simply describes the action in the play as "a spectacular act of holy violence and revenge". Likewise, David Loewenstein remarks that "the destruction and vengeance depicted in Samson Agonistes, then, dramatizes a kind of awesome religious terror". Gordon Teskey describes the plot of the work when he says, "delirious violence of the hero of Samson Agonistes, who cancels the Philistine hallucination of a unified and harmonious world". Against the backdrop of the challenge posed by suicide terrorism, Arata Takeda points to ethical implications arising from Samson's "brutal massacre committed against civilians attending a religious feast" and the following "lyrical extolment of the suicide mass murder".

The play itself suggests the horror within the actions through descriptive phrases, including "evil news" (line 538), "this so horrid spectacle" (line 1542), "the place of horror" (line 1550) and "the sad event" (line 1551). Although Samson is the hero and he causes the violence, Elizabeth Sauer points out that "Milton devotes nearly twice as many lines to the Chorus’ reactions in the denouement than to the Messenger's description of the catastrophe in order to deemphasize spectacle and performance and instead to highlight the interior drama while encouraging active interpretation of the reported events".

Women

The play, focusing around the betrayal of Samson at the hands of Dalila, his wife, produces a negative portrayal of love and love's effects. Women, and men's desire for women, are connected to idolatry against God and the idea that there is no possibility for the sacred within the bonds of marital love. Samson, who is both holy and desirous of Dalila, is seduced into betraying the source of his strength, and thus betrays God. He is emasculated, through blindness, because of his sexual desires. The Chorus, after Dalila attempts to seduce Samson again, criticises women for being deceptive.

Samson's argument against Dalila is to discuss the proper role of a wife but also the superiority of men. The depiction of Dalila, and women, is similar to that in Milton's divorce tracts and, as John Guillory states and then asks, "We scarcely need to observe that Samson Agonistes assumes the subjection of women, a practice to which Milton gives his unequivocal endorsement; but is there any sense in which that practice of subjection is modified by the contemporaneous form of the sexual divisions of labor?". A wife is supposed to help a husband, and the husband, regardless of the status of the woman, is supposed to have the superior status. In blaming Dalila, he rationalises his actions and removes blame from himself, which is similar to what Adam attempts in Paradise Lost after the fall. However, Samson develops through the play and Dalila reveals that she is concerned only with her status among her people. This places Dalila in a different role from Milton's Eve. Instead, she is an emasculating force and represents Samson's past failings.

Religion

Samson undergoes despair when he loses God's favour in the form of his strength. In his searching for a way to return to being true to God and to serve his will, Samson is compared to the non-conformists after the English Restoration who are attacked and abused simply because they, according to their own view, serve God in the correct way.

Blindness

As blindness overtook Milton, it becomes a major trope in Samson Agonistes, and is seen also in Paradise Lost (3.22–55) and his 19th Sonnet. Many scholars have written about the impact of Milton's increasing blindness on his works. This recurrence of blindness came after Milton temporarily gave up his poetry to work for Oliver Cromwell and the Commonwealth government. He continued this service even though his eyesight was failing and he knew that he was hastening his own blindness. The correlation is significant to the Agonistes plot: Milton describes Samson as being "Eyeless in Gaza", a phrase that has become the most quoted line of Agonistes. Novelist Aldous Huxley used it as the title for his 1936 novel Eyeless in Gaza.

Samson's blindness, however, is not exactly analogous to Milton's. Rather, Samson's blindness plays various symbolic roles. One is the correlation between Samson's inner blindness as well as outer, the fact that he believes his "intimate impulses" to be divine messages, yet is never in any way divinely affirmed in this, unlike the rest of Milton's divinely influenced characters. Samson's inability to see that his inner vision does not correlate to divine vision is manifest in his physical blindness. It also plays on his blindness to reason, leading him to act hastily, plus the fact that he is so easily deceived by Delila, "blinded" by her feminine wiles. Some of the chorus's lines in Samson Agonistes are rhymed, thus suggesting a return of the "chain of rhymes", which itself reflects upon Samson's imprisonment.