The history of mathematical notation includes the commencement, progress, and cultural diffusion of mathematical symbols and the conflict of the methods of notation confronted in a notation's move to popularity or inconspicuousness. Mathematical notation comprises the symbols used to write mathematical equations and formulas. Notation generally implies a set of well-defined representations of quantities and symbols operators. The history includes Hindu–Arabic numerals, letters from the Roman, Greek, Hebrew, and German alphabets, and a host of symbols invented by mathematicians over the past several centuries.

The development of mathematical notation can be divided in stages. The "rhetorical" stage is where calculations are performed by words and no symbols are used. The "syncopated" stage is where frequently used operations and quantities are represented by symbolic syntactical abbreviations. From ancient times through the post-classical age, bursts of mathematical creativity were often followed by centuries of stagnation. As the early modern age opened and the worldwide spread of knowledge began, written examples of mathematical developments came to light. The "symbolic" stage is where comprehensive systems of notation supersede rhetoric. Beginning in Italy in the 16th century, new mathematical developments, interacting with new scientific discoveries, were made at an increasing pace that continues through the present day. This symbolic system was in use by medieval Indian mathematicians and in Europe since the middle of the 17th century, and has continued to develop in the contemporary era.

The area of study known as the history of mathematics is primarily an investigation into the origin of discoveries in mathematics and, the focus here, the investigation into the mathematical methods and notation of the past.

Rhetorical stage

Although the history commences with that of the Ionian schools, there is no doubt that those Ancient Greeks who paid attention to it were largely indebted to the previous investigations of the Ancient Egyptians and Ancient Phoenicians. Numerical notation's distinctive feature, i.e. symbols having local as well as intrinsic values (arithmetic), implies a state of civilization at the period of its invention. Our knowledge of the mathematical attainments of these early peoples, to which this section is devoted, is imperfect and the following brief notes be regarded as a summary of the conclusions which seem most probable, and the history of mathematics begins with the symbolic sections.

Many areas of mathematics began with the study of real world problems, before the underlying rules and concepts were identified and defined as abstract structures. For example, geometry has its origins in the calculation of distances and areas in the real world; algebra started with methods of solving problems in arithmetic.

There can be no doubt that most early peoples which have left records knew something of numeration and mechanics, and that a few were also acquainted with the elements of land-surveying. In particular, the Egyptians paid attention to geometry and numbers, and the Phoenicians to practical arithmetic, book-keeping, navigation, and land-surveying. The results attained by these people seem to have been accessible, under certain conditions, to travelers. It is probable that the knowledge of the Egyptians and Phoenicians was largely the result of observation and measurement, and represented the accumulated experience of many ages.

Beginning of notation

Written mathematics began with numbers expressed as tally marks, with each tally representing a single unit. The numerical symbols consisted probably of strokes or notches cut in wood or stone, and intelligible alike to all nations. For example, one notch in a bone represented one animal, or person, or anything else. The peoples with whom the Greeks of Asia Minor (amongst whom notation in western history begins) were likely to have come into frequent contact were those inhabiting the eastern littoral of the Mediterranean: and Greek tradition uniformly assigned the special development of geometry to the Egyptians, and that of the science of numbers either to the Egyptians or to the Phoenicians.

The Ancient Egyptians had a symbolic notation which was the numeration by Hieroglyphics. The Egyptian mathematics had a symbol for one, ten, one hundred, one thousand, ten thousand, one hundred thousand, and one million. Smaller digits were placed on the left of the number, as they are in Hindu–Arabic numerals. Later, the Egyptians used hieratic instead of hieroglyphic script to show numbers. Hieratic was more like cursive and replaced several groups of symbols with individual ones. For example, the four vertical lines used to represent four were replaced by a single horizontal line. This is found in the Rhind Mathematical Papyrus (c. 2000–1800 BC) and the Moscow Mathematical Papyrus (c. 1890 BC). The system the Egyptians used was discovered and modified by many other civilizations in the Mediterranean. The Egyptians also had symbols for basic operations: legs going forward represented addition, and legs walking backward to represent subtraction.

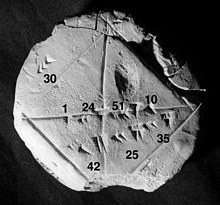

The Mesopotamians had symbols for each power of ten. Later, they wrote their numbers in almost exactly the same way done in modern times. Instead of having symbols for each power of ten, they would just put the coefficient of that number. Each digit was separated by only a space, but by the time of Alexander the Great, they had created a symbol that represented zero and was a placeholder. The Mesopotamians also used a sexagesimal system, that is base sixty. It is this system that is used in modern times when measuring time and angles. Babylonian mathematics is derived from more than 400 clay tablets unearthed since the 1850s. Written in Cuneiform script, tablets were inscribed whilst the clay was moist, and baked hard in an oven or by the heat of the sun. Some of these appear to be graded homework. The earliest evidence of written mathematics dates back to the ancient Sumerians and the system of metrology from 3000 BC. From around 2500 BC onwards, the Sumerians wrote multiplication tables on clay tablets and dealt with geometrical exercises and division problems. The earliest traces of the Babylonian numerals also date back to this period.

The majority of Mesopotamian clay tablets date from 1800 to 1600 BC, and cover topics which include fractions, algebra, quadratic and cubic equations, and the calculation of regular, reciprocal and pairs. The tablets also include multiplication tables and methods for solving linear and quadratic equations. The Babylonian tablet YBC 7289 gives an approximation of √2 accurate to five decimal places. Babylonian mathematics were written using a sexagesimal (base-60) numeral system. From this derives the modern-day usage of 60 seconds in a minute, 60 minutes in an hour, and 360 (60 × 6) degrees in a circle, as well as the use of minutes and seconds of arc to denote fractions of a degree. Babylonian advances in mathematics were facilitated by the fact that 60 has many divisors: the reciprocal of any integer which is a multiple of divisors of 60 has a finite expansion in base 60. (In decimal arithmetic, only reciprocals of multiples of 2 and 5 have finite decimal expansions.) Also, unlike the Egyptians, Greeks, and Romans, the Babylonians had a true place-value system, where digits written in the left column represented larger values, much as in the decimal system. They lacked, however, an equivalent of the decimal point, and so the place value of a symbol often had to be inferred from the context.

Syncopated stage

The last words attributed to Archimedes are "Do not disturb my circles", a reference to the circles in the mathematical drawing that he was studying when disturbed by the Roman soldier.

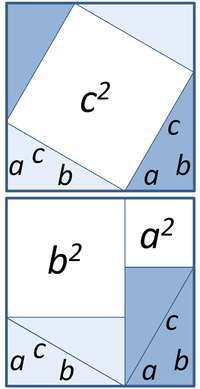

The history of mathematics cannot with certainty be traced back to any school or period before that of the Ionian Greeks, but the subsequent history may be divided into periods, the distinctions between which are tolerably well marked. Greek mathematics, which originated with the study of geometry, tended from its commencement to be deductive and scientific. Since the fourth century AD, Pythagoras has commonly been given credit for discovering the Pythagorean theorem, a theorem in geometry that states that in a right-angled triangle the area of the square on the hypotenuse (the side opposite the right angle) is equal to the sum of the areas of the squares of the other two sides. The ancient mathematical texts are available with the prior mentioned Ancient Egyptians notation and with Plimpton 322 (Babylonian mathematics c. 1900 BC). The study of mathematics as a subject in its own right begins in the 6th century BC with the Pythagoreans, who coined the term "mathematics" from the ancient Greek μάθημα (mathema), meaning "subject of instruction".

Plato's influence has been especially strong in mathematics and the sciences. He helped to distinguish between pure and applied mathematics by widening the gap between "arithmetic", now called number theory and "logistic", now called arithmetic. Greek mathematics greatly refined the methods (especially through the introduction of deductive reasoning and mathematical rigor in proofs) and expanded the subject matter of mathematics. Aristotle is credited with what later would be called the law of excluded middle.

Abstract Mathematics is what treats of magnitude or quantity, absolutely and generally conferred, without regard to any species of particular magnitude, such as arithmetic and geometry, In this sense, abstract mathematics is opposed to mixed mathematics, wherein simple and abstract properties, and the relations of quantities primitively considered in mathematics, are applied to sensible objects, and by that means become intermixed with physical considerations, such as in hydrostatics, optics, and navigation.

Archimedes is generally considered to be the greatest mathematician of antiquity and one of the greatest of all time. He used the method of exhaustion to calculate the area under the arc of a parabola with the summation of an infinite series, and gave a remarkably accurate approximation of pi. He also defined the spiral bearing his name, formulae for the volumes of surfaces of revolution and an ingenious system for expressing very large numbers.

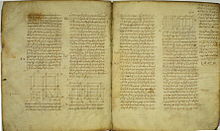

The prop. 31, 32 and 33 of the book of Euclid XI, which is located in vol. 2 of the manuscript, the sheets 207 to – 208 recto.

In the historical development of geometry, the steps in the abstraction of geometry were made by the ancient Greeks. Euclid's Elements being the earliest extant documentation of the axioms of plane geometry— though Proclus tells of an earlier axiomatisation by Hippocrates of Chios. Euclid's Elements (c. 300 BC) is one of the oldest extant Greek mathematical treatises and consisted of 13 books written in Alexandria; collecting theorems proven by other mathematicians, supplemented by some original work. The document is a successful collection of definitions, postulates (axioms), propositions (theorems and constructions), and mathematical proofs of the propositions. Euclid's first theorem is a lemma that possesses properties of prime numbers. The influential thirteen books cover Euclidean geometry, geometric algebra, and the ancient Greek version of algebraic systems and elementary number theory. It was ubiquitous in the Quadrivium and is instrumental in the development of logic, mathematics, and science.

Diophantus of Alexandria was author of a series of books called Arithmetica, many of which are now lost. These texts deal with solving algebraic equations. Boethius provided a place for mathematics in the curriculum in the 6th century when he coined the term quadrivium to describe the study of arithmetic, geometry, astronomy, and music. He wrote De institutione arithmetica, a free translation from the Greek of Nicomachus's Introduction to Arithmetic; De institutione musica, also derived from Greek sources; and a series of excerpts from Euclid's Elements. His works were theoretical, rather than practical, and were the basis of mathematical study until the recovery of Greek and Arabic mathematical works.

Acrophonic and Milesian numeration

The Greeks employed Attic numeration, which was based on the system of the Egyptians and was later adapted and used by the Romans. Greek numerals one through four were vertical lines, as in the hieroglyphics. The symbol for five was the Greek letter Π (pi), which is the letter of the Greek word for five, pente. Numbers six through nine were pente with vertical lines next to it. Ten was represented by the letter (Δ) of the word for ten, deka, one hundred by the letter from the word for hundred, etc.

The Ionian numeration used their entire alphabet including three archaic letters. The numeral notation of the Greeks, though far less convenient than that now in use, was formed on a perfectly regular and scientific plan, and could be used with tolerable effect as an instrument of calculation, to which purpose the Roman system was totally inapplicable. The Greeks divided the twenty-four letters of their alphabet into three classes, and, by adding another symbol to each class, they had characters to represent the units, tens, and hundreds. (Jean Baptiste Joseph Delambre's Astronomie Ancienne, t. ii.)

| Α (α) | Β (β) | Г (γ) | Δ (δ) | Ε (ε) | Ϝ (ϝ) | Ζ (ζ) | Η (η) | θ (θ) | Ι (ι) | Κ (κ) | Λ (λ) | Μ (μ) | Ν (ν) | Ξ (ξ) | Ο (ο) | Π (π) | Ϟ (ϟ) | Ρ (ρ) | Σ (σ) | Τ (τ) | Υ (υ) | Φ (φ) | Χ (χ) | Ψ (ψ) | Ω (ω) | Ϡ (ϡ) |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 20 | 30 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 70 | 80 | 90 | 100 | 200 | 300 | 400 | 500 | 600 | 700 | 800 | 900 |

This system appeared in the third century BC, before the letters digamma (Ϝ), koppa (Ϟ), and sampi (Ϡ) became obsolete. When lowercase letters became differentiated from upper case letters, the lower case letters were used as the symbols for notation. Multiples of one thousand were written as the nine numbers with a stroke in front of them: thus one thousand was ",α", two-thousand was ",β", etc. M (for μὐριοι, as in "myriad") was used to multiply numbers by ten thousand. For example, the number 88,888,888 would be written as M,ηωπη*ηωπη

Greek mathematical reasoning was almost entirely geometric (albeit often used to reason about non-geometric subjects such as number theory), and hence the Greeks had no interest in algebraic symbols. The great exception was Diophantus of Alexandria, the great algebraist. His Arithmetica was one of the texts to use symbols in equations. It was not completely symbolic, but was much more so than previous books. An unknown number was called s. The square of s was ; the cube was ; the fourth power was ; and the fifth power was .

Chinese mathematical notation

The Chinese used numerals that look much like the tally system. Numbers one through four were horizontal lines. Five was an X between two horizontal lines; it looked almost exactly the same as the Roman numeral for ten. Nowadays, the huāmǎ system is only used for displaying prices in Chinese markets or on traditional handwritten invoices.

In the history of the Chinese, there were those who were familiar with the sciences of arithmetic, geometry, mechanics, optics, navigation, and astronomy. Mathematics in China emerged independently by the 11th century BC. It is almost certain that the Chinese were acquainted with several geometrical or rather architectural implements; with mechanical machines; that they knew of the characteristic property of the magnetic needle; and were aware that astronomical events occurred in cycles. Chinese of that time had made attempts to classify or extend the rules of arithmetic or geometry which they knew, and to explain the causes of the phenomena with which they were acquainted beforehand. The Chinese independently developed very large and negative numbers, decimals, a place value decimal system, a binary system, algebra, geometry, and trigonometry.

Chinese mathematics made early contributions, including a place value system. The geometrical theorem known to the ancient Chinese were acquainted was applicable in certain cases (namely the ratio of sides). It is that geometrical theorems which can be demonstrated in the quasi-experimental way of superposition were also known to them. In arithmetic their knowledge seems to have been confined to the art of calculation by means of the swan-pan, and the power of expressing the results in writing. Our knowledge of the early attainments of the Chinese, slight though it is, is more complete than in the case of most of their contemporaries. It is thus instructive, and serves to illustrate the fact, that it can be known a nation may possess considerable skill in the applied arts with but our knowledge of the later mathematics on which those arts are founded can be scarce. Knowledge of Chinese mathematics before 254 BC is somewhat fragmentary, and even after this date the manuscript traditions are obscure. Dates centuries before the classical period are generally considered conjectural by Chinese scholars unless accompanied by verified archaeological evidence.

As in other early societies the focus was on astronomy in order to perfect the agricultural calendar, and other practical tasks, and not on establishing formal systems. The Chinese Board of Mathematics duties were confined to the annual preparation of an almanac, the dates and predictions in which it regulated. Ancient Chinese mathematicians did not develop an axiomatic approach, but made advances in algorithm development and algebra. The achievement of Chinese algebra reached its zenith in the 13th century, when Zhu Shijie invented method of four unknowns.

As a result of obvious linguistic and geographic barriers, as well as content, Chinese mathematics and that of the mathematics of the ancient Mediterranean world are presumed to have developed more or less independently up to the time when The Nine Chapters on the Mathematical Art reached its final form, while the Writings on Reckoning and Huainanzi are roughly contemporary with classical Greek mathematics. Some exchange of ideas across Asia through known cultural exchanges from at least Roman times is likely. Frequently, elements of the mathematics of early societies correspond to rudimentary results found later in branches of modern mathematics such as geometry or number theory. The Pythagorean theorem for example, has been attested to the time of the Duke of Zhou. Knowledge of Pascal's triangle has also been shown to have existed in China centuries before Pascal, such as by Shen Kuo.

The state of trigonometry in China slowly began to change and advance during the Song Dynasty (960–1279), where Chinese mathematicians began to express greater emphasis for the need of spherical trigonometry in calendrical science and astronomical calculations. The polymath Chinese scientist, mathematician and official Shen Kuo (1031–1095) used trigonometric functions to solve mathematical problems of chords and arcs. Sal Restivo writes that Shen's work in the lengths of arcs of circles provided the basis for spherical trigonometry developed in the 13th century by the mathematician and astronomer Guo Shoujing (1231–1316). As the historians L. Gauchet and Joseph Needham state, Guo Shoujing used spherical trigonometry in his calculations to improve the calendar system and Chinese astronomy. The mathematical science of the Chinese would incorporate the work and teaching of Arab missionaries with knowledge of spherical trigonometry who had come to China in the course of the thirteenth century.

Indian & Arabic numerals and notation

Although the origin of our present system of numerical notation is ancient, there is no doubt that it was in use among the Hindus over two thousand years ago. The algebraic notation of the Indian mathematician, Brahmagupta, was syncopated. Addition was indicated by placing the numbers side by side, subtraction by placing a dot over the subtrahend (the number to be subtracted), and division by placing the divisor below the dividend, similar to our notation but without the bar. Multiplication, evolution, and unknown quantities were represented by abbreviations of appropriate terms. The Hindu–Arabic numeral system and the rules for the use of its operations, in use throughout the world today, likely evolved over the course of the first millennium AD in India and was transmitted to the west via Islamic mathematics.

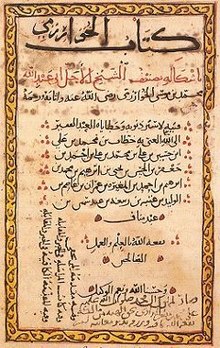

Despite their name, Arabic numerals have roots in India. The reason for this misnomer is Europeans saw the numerals used in an Arabic book, Concerning the Hindu Art of Reckoning, by Mohommed ibn-Musa al-Khwarizmi. Al-Khwārizmī wrote several important books on the Hindu–Arabic numerals and on methods for solving equations. His book On the Calculation with Hindu Numerals, written about 825, along with the work of Al-Kindi, were instrumental in spreading Indian mathematics and Indian numerals to the West. Al-Khwarizmi did not claim the numerals as Arabic, but over several Latin translations, the fact that the numerals were Indian in origin was lost. The word algorithm is derived from the Latinization of Al-Khwārizmī's name, Algoritmi, and the word algebra from the title of one of his works, Al-Kitāb al-mukhtaṣar fī hīsāb al-ğabr wa’l-muqābala (The Compendious Book on Calculation by Completion and Balancing).

Islamic mathematics developed and expanded the mathematics known to Central Asian civilizations. Al-Khwārizmī gave an exhaustive explanation for the algebraic solution of quadratic equations with positive roots, and Al-Khwārizmī was to teach algebra in an elementary form and for its own sake. Al-Khwārizmī also discussed the fundamental method of "reduction" and "balancing", referring to the transposition of subtracted terms to the other side of an equation, that is, the cancellation of like terms on opposite sides of the equation. This is the operation which al-Khwārizmī originally described as al-jabr. His algebra was also no longer concerned "with a series of problems to be resolved, but an exposition which starts with primitive terms in which the combinations must give all possible prototypes for equations, which henceforward explicitly constitute the true object of study." Al-Khwārizmī also studied an equation for its own sake and "in a generic manner, insofar as it does not simply emerge in the course of solving a problem, but is specifically called on to define an infinite class of problems."

Al-Karaji, in his treatise al-Fakhri, extends the methodology to incorporate integer powers and integer roots of unknown quantities. The historian of mathematics, F. Woepcke, praised Al-Karaji for being "the first who introduced the theory of algebraic calculus." Also in the 10th century, Abul Wafa translated the works of Diophantus into Arabic. Ibn al-Haytham would develop analytic geometry. Al-Haytham derived the formula for the sum of the fourth powers, using a method that is readily generalizable for determining the general formula for the sum of any integral powers. Al-Haytham performed an integration in order to find the volume of a paraboloid, and was able to generalize his result for the integrals of polynomials up to the fourth degree. In the late 11th century, Omar Khayyam would develop algebraic geometry, wrote Discussions of the Difficulties in Euclid, and wrote on the general geometric solution to cubic equations. Nasir al-Din Tusi (Nasireddin) made advances in spherical trigonometry. Muslim mathematicians during this period include the addition of the decimal point notation to the Arabic numerals.

The modern Arabic numeral symbols used around the world first appeared in Islamic North Africa in the 10th century. A distinctive Western Arabic variant of the Eastern Arabic numerals began to emerge around the 10th century in the Maghreb and Al-Andalus (sometimes called ghubar numerals, though the term is not always accepted), which are the direct ancestor of the modern Arabic numerals used throughout the world.

Many Greek and Arabic texts on mathematics were then translated into Latin, which led to further development of mathematics in medieval Europe. In the 12th century, scholars traveled to Spain and Sicily seeking scientific Arabic texts, including al-Khwārizmī's and the complete text of Euclid's Elements. One of the European books that advocated using the numerals was Liber Abaci, by Leonardo of Pisa, better known as Fibonacci. Liber Abaci is better known for the mathematical problem Fibonacci wrote in it about a population of rabbits. The growth of the population ended up being a Fibonacci sequence, where a term is the sum of the two preceding terms.

Symbolic stage

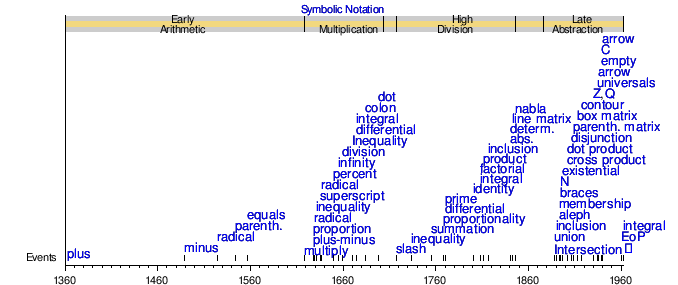

- Symbols by popular introduction date

Early arithmetic and multiplication

The transition to symbolic algebra, where only symbols are used, can first be seen in the work of Ibn al-Banna' al-Marrakushi (1256–1321) and Abū al-Ḥasan ibn ʿAlī al-Qalaṣādī (1412–1482). Al-Qalasādī was the last major medieval Arab algebraist, who improved on the algebraic notation earlier used in the Maghreb by Ibn al-Banna. In contrast to the syncopated notations of their predecessors, Diophantus and Brahmagupta, which lacked symbols for mathematical operations, al-Qalasadi's algebraic notation was the first to have symbols for these functions and was thus "the first steps toward the introduction of algebraic symbolism." He represented mathematical symbols using characters from the Arabic alphabet.

The 14th century saw the development of new mathematical concepts to investigate a wide range of problems. The two widely used arithmetic symbols are addition and subtraction, + and −. The plus sign was used by 1360 by Nicole Oresme in his work Algorismus proportionum. It is thought an abbreviation for "et", meaning "and" in Latin, in much the same way the ampersand sign also began as "et". Oresme at the University of Paris and the Italian Giovanni di Casali independently provided graphical demonstrations of the distance covered by a body undergoing uniformly accelerated motion, asserting that the area under the line depicting the constant acceleration and represented the total distance traveled. The minus sign was used in 1489 by Johannes Widmann in Mercantile Arithmetic or Behende und hüpsche Rechenung auff allen Kauffmanschafft,. Widmann used the minus symbol with the plus symbol, to indicate deficit and surplus, respectively. In Summa de arithmetica, geometria, proportioni e proportionalità, Luca Pacioli used symbols for plus and minus symbols and contained algebra.

In the 15th century, Ghiyath al-Kashi computed the value of π to the 16th decimal place. Kashi also had an algorithm for calculating nth roots. In 1533, Regiomontanus's table of sines and cosines were published. Scipione del Ferro and Niccolò Fontana Tartaglia discovered solutions for cubic equations. Gerolamo Cardano published them in his 1545 book Ars Magna, together with a solution for the quartic equations, discovered by his student Lodovico Ferrari. The radical symbol for square root was introduced by Christoph Rudolff. Michael Stifel's important work Arithmetica integra contained important innovations in mathematical notation. In 1556, Niccolò Tartaglia used parentheses for precedence grouping. In 1557 Robert Recorde published The Whetstone of Witte which introduced the equal sign (=), as well as plus and minus signs for the English reader. In 1564, Gerolamo Cardano analyzed games of chance beginning the early stages of probability theory. In 1572 Rafael Bombelli published his L'Algebra in which he showed how to deal with the imaginary quantities that could appear in Cardano's formula for solving cubic equations. Simon Stevin's book De Thiende ('the art of tenths'), published in Dutch in 1585, contained a systematic treatment of decimal notation, which influenced all later work on the real number system. The New algebra (1591) of François Viète introduced the modern notational manipulation of algebraic expressions. For navigation and accurate maps of large areas, trigonometry grew to be a major branch of mathematics. Bartholomaeus Pitiscus coin the word "trigonometry", publishing his Trigonometria in 1595.

John Napier is best known as the inventor of logarithms and made common the use of the decimal point in arithmetic and mathematics. After Napier, Edmund Gunter created the logarithmic scales (lines, or rules) upon which slide rules are based, it was William Oughtred who used two such scales sliding by one another to perform direct multiplication and division; and he is credited as the inventor of the slide rule in 1622. In 1631 Oughtred introduced the multiplication sign (×) his proportionality sign, and abbreviations sin and cos for the sine and cosine functions. Albert Girard also used the abbreviations 'sin', 'cos' and 'tan' for the trigonometric functions in his treatise.

Johannes Kepler was one of the pioneers of the mathematical applications of infinitesimals. René Descartes is credited as the father of analytical geometry, the bridge between algebra and geometry, crucial to the discovery of infinitesimal calculus and analysis. In the 17th century, Descartes introduced Cartesian co-ordinates which allowed the development of analytic geometry. Blaise Pascal influenced mathematics throughout his life. His Traité du triangle arithmétique ("Treatise on the Arithmetical Triangle") of 1653 described a convenient tabular presentation for binomial coefficients. Pierre de Fermat and Blaise Pascal would investigate probability. John Wallis introduced the infinity symbol. He similarly used this notation for infinitesimals. In 1657, Christiaan Huygens published the treatise on probability, On Reasoning in Games of Chance.

Johann Rahn introduced the division sign (÷, an obelus variant repurposed) and the therefore sign in 1659. William Jones used π in Synopsis palmariorum mathesios in 1706 because it is the initial letter of the Greek word perimetron (περιμετρον), which means perimeter in Greek. This usage was popularized in 1737 by Euler. In 1734, Pierre Bouguer used double horizontal bar below the inequality sign.

Derivatives notation: Leibniz and Newton

| Derivative notations | |

|---|---|

| |

The study of linear algebra emerged from the study of determinants, which were used to solve systems of linear equations. Calculus had two main systems of notation, each created by one of the creators: that developed by Isaac Newton and the notation developed by Gottfried Leibniz. Leibniz's is the notation used most often today. Newton's was simply a dot or dash placed above the function. In modern usage, this notation generally denotes derivatives of physical quantities with respect to time, and is used frequently in the science of mechanics. Leibniz, on the other hand, used the letter d as a prefix to indicate differentiation, and introduced the notation representing derivatives as if they were a special type of fraction.[note 36] This notation makes explicit the variable with respect to which the derivative of the function is taken. Leibniz also created the integral symbol. The symbol is an elongated S, representing the Latin word Summa, meaning "sum". When finding areas under curves, integration is often illustrated by dividing the area into infinitely many tall, thin rectangles, whose areas are added. Thus, the integral symbol is an elongated s, for sum.

High division operators and functions

Letters of the alphabet in this time were to be used as symbols of quantity; and although much diversity existed with respect to the choice of letters, there were to be several universally recognized rules in the following history. Here thus in the history of equations the first letters of the alphabet were indicatively known as coefficients, the last letters the unknown terms (an incerti ordinis). In algebraic geometry, again, a similar rule was to be observed, the last letters of the alphabet there denoting the variable or current coordinates. Certain letters, such as , , etc., were by universal consent appropriated as symbols of the frequently occurring numbers 3.14159 ..., and 2.7182818 ...., etc., and their use in any other acceptation was to be avoided as much as possible. Letters, too, were to be employed as symbols of operation, and with them other previously mentioned arbitrary operation characters. The letters , elongated were to be appropriated as operative symbols in the differential calculus and integral calculus, and Σ in the calculus of differences. In functional notation, a letter, as a symbol of operation, is combined with another which is regarded as a symbol of quantity.

Beginning in 1718, Thomas Twinin used the division slash (solidus), deriving it from the earlier Arabic horizontal fraction bar. Pierre-Simon, marquis de Laplace developed the widely used Laplacian differential operator. In 1750, Gabriel Cramer developed "Cramer's Rule" for solving linear systems.

Euler and prime notations

Leonhard Euler was one of the most prolific mathematicians in history, and also a prolific inventor of canonical notation. His contributions include his use of e to represent the base of natural logarithms. It is not known exactly why was chosen, but it was probably because the four letters of the alphabet were already commonly used to represent variables and other constants. Euler used to represent pi consistently. The use of was suggested by William Jones, who used it as shorthand for perimeter. Euler used to represent the square root of negative one, although he earlier used it as an infinite number. For summation, Euler used sigma, Σ. For functions, Euler used the notation to represent a function of . In 1730, Euler wrote the gamma function. In 1736, Euler produced his paper on the Seven Bridges of Königsberg initiating the study of graph theory.

The mathematician William Emerson would develop the proportionality sign. Much later in the abstract expressions of the value of various proportional phenomena, the parts-per notation would become useful as a set of pseudo units to describe small values of miscellaneous dimensionless quantities. Marquis de Condorcet, in 1768, advanced the partial differential sign. In 1771, Alexandre-Théophile Vandermonde deduced the importance of topological features when discussing the properties of knots related to the geometry of position. Between 1772 and 1788, Joseph-Louis Lagrange re-formulated the formulas and calculations of Classical "Newtonian" mechanics, called Lagrangian mechanics. The prime symbol for derivatives was also made by Lagrange.

But in our opinion truths of this kind should be drawn from notions rather than from notations.

— Carl Friedrich Gauss

Gauss, Hamilton, and Matrix notations

At the turn of the 19th century, Carl Friedrich Gauss developed the identity sign for congruence relation and, in Quadratic reciprocity, the integral part. Gauss contributed functions of complex variables, in geometry, and on the convergence of series. He gave the satisfactory proofs of the fundamental theorem of algebra and of the quadratic reciprocity law. Gauss developed the theory of solving linear systems by using Gaussian elimination, which was initially listed as an advancement in geodesy. He would also develop the product sign. Also in this time, Niels Henrik Abel and Évariste Galois conducted their work on the solvability of equations, linking group theory and field theory.

After the 1800s, Christian Kramp would promote factorial notation during his research in generalized factorial function which applied to non-integers. Joseph Diaz Gergonne introduced the set inclusion signs. Peter Gustav Lejeune Dirichlet developed Dirichlet L-functions to give the proof of Dirichlet's theorem on arithmetic progressions and began analytic number theory. In 1828, Gauss proved his Theorema Egregium (remarkable theorem in Latin), establishing property of surfaces. In the 1830s, George Green developed Green's function. In 1829. Carl Gustav Jacob Jacobi publishes Fundamenta nova theoriae functionum ellipticarum with his elliptic theta functions. By 1841, Karl Weierstrass, the "father of modern analysis", elaborated on the concept of absolute value and the determinant of a matrix.

Matrix notation would be more fully developed by Arthur Cayley in his three papers, on subjects which had been suggested by reading the Mécanique analytique of Lagrange and some of the works of Laplace. Cayley defined matrix multiplication and matrix inverses. Cayley used a single letter to denote a matrix, thus treating a matrix as an aggregate object. He also realized the connection between matrices and determinants, and wrote "There would be many things to say about this theory of matrices which should, it seems to me, precede the theory of determinants".

[... The mathematical quaternion] has, or at least involves a reference to, four dimensions.

— William Rowan Hamilton

William Rowan Hamilton would introduce the nabla symbol for vector differentials. This was previously used by Hamilton as a general-purpose operator sign. Hamilton reformulated Newtonian mechanics, now called Hamiltonian mechanics. This work has proven central to the modern study of classical field theories such as electromagnetism. This was also important to the development of quantum mechanics. In mathematics, he is perhaps best known as the inventor of quaternion notation and biquaternions. Hamilton also introduced the word "tensor" in 1846. James Cockle would develop the tessarines and, in 1849, coquaternions. In 1848, James Joseph Sylvester introduced into matrix algebra the term matrix.

Maxwell, Clifford, and Ricci notations

Maxwell's most prominent achievement was to formulate a set of equations that united previously unrelated observations, experiments, and equations of electricity, magnetism, and optics into a consistent theory.

In 1864 James Clerk Maxwell reduced all of the then current knowledge of electromagnetism into a linked set of differential equations with 20 equations in 20 variables, contained in A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field. (See Maxwell's equations.) The method of calculation which it is necessary to employ was given by Lagrange, and afterwards developed, with some modifications, by Hamilton's equations. It is usually referred to as Hamilton's principle; when the equations in the original form are used they are known as Lagrange's equations. In 1871 Richard Dedekind called a set of real or complex numbers which is closed under the four arithmetic operations a field. In 1873 Maxwell presented A Treatise on Electricity and Magnetism.

In 1878, William Kingdon Clifford published his Elements of Dynamic. Clifford developed split-biquaternions, which he called algebraic motors. Clifford obviated quaternion study by separating the dot product and cross product of two vectors from the complete quaternion notation. This approach made vector calculus available to engineers and others working in three dimensions and skeptical of the lead–lag effect in the fourth dimension. The common vector notations are used when working with vectors which are spatial or more abstract members of vector spaces, while angle notation (or phasor notation) is a notation used in electronics.

In 1881, Leopold Kronecker defined what he called a "domain of rationality", which is a field extension of the field of rational numbers in modern terms. In 1882, Hüseyin Tevfik Paşa wrote the book titled "Linear Algebra". Lord Kelvin's aetheric atom theory (1860s) led Peter Guthrie Tait, in 1885, to publish a topological table of knots with up to ten crossings known as the Tait conjectures. In 1893, Heinrich M. Weber gave the clear definition of an abstract field. Tensor calculus was developed by Gregorio Ricci-Curbastro between 1887 and 1896, presented in 1892 under the title absolute differential calculus, and the contemporary usage of "tensor" was stated by Woldemar Voigt in 1898. In 1895, Henri Poincaré published Analysis Situs. In 1897, Charles Proteus Steinmetz would publish Theory and Calculation of Alternating Current Phenomena, with the assistance of Ernst J. Berg.

From formula mathematics to tensors

The above proposition is occasionally useful.

— Bertrand Russell

In 1895 Giuseppe Peano issued his Formulario mathematico, an effort to digest mathematics into terse text based on special symbols. He would provide a definition of a vector space and linear map. He would also introduce the intersection sign, the union sign, the membership sign (is an element of), and existential quantifier (there exists). Peano would pass to Bertrand Russell his work in 1900 at a Paris conference; it so impressed Russell that Russell too was taken with the drive to render mathematics more concisely. The result was Principia Mathematica written with Alfred North Whitehead. This treatise marks a watershed in modern literature where symbol became dominant.

Ricci-Curbastro and Tullio Levi-Civita popularized the tensor index notation around 1900.

Mathematical logic and abstraction

| Abstraction | |

|---|---|

At the beginning of this period, Felix Klein's "Erlangen program" identified the underlying theme of various geometries, defining each of them as the study of properties invariant under a given group of symmetries. This level of abstraction revealed connections between geometry and abstract algebra. Georg Cantor would introduce the aleph symbol for cardinal numbers of transfinite sets. His notation for the cardinal numbers was the Hebrew letter (aleph) with a natural number subscript; for the ordinals he employed the Greek letter ω (omega). This notation is still in use today in ordinal notation of a finite sequence of symbols from a finite alphabet which names an ordinal number according to some scheme which gives meaning to the language. His theory created a great deal of controversy. Cantor would, in his study of Fourier series, consider point sets in Euclidean space.

After the turn of the 20th century, Josiah Willard Gibbs would in physical chemistry introduce middle dot for dot product and the multiplication sign for cross products. He would also supply notation for the scalar and vector products, which was introduced in Vector Analysis. In 1904, Ernst Zermelo promotes axiom of choice and his proof of the well-ordering theorem. Bertrand Russell would shortly afterward introduce logical disjunction (OR) in 1906. Also in 1906, Poincaré would publish On the Dynamics of the Electron and Maurice Fréchet introduced metric space. Later, Gerhard Kowalewski and Cuthbert Edmund Cullis would successively introduce matrices notation, parenthetical matrix and box matrix notation respectively. After 1907, mathematicians studied knots from the point of view of the knot group and invariants from homology theory. In 1908, Joseph Wedderburn's structure theorems were formulated for finite-dimensional algebras over a field. Also in 1908, Ernst Zermelo proposed "definite" property and the first axiomatic set theory, Zermelo set theory. In 1910 Ernst Steinitz published the influential paper Algebraic Theory of Fields. In 1911, Steinmetz would publish Theory and Calculation of Transient Electric Phenomena and Oscillations.

Albert Einstein, in 1916, introduced the Einstein notation which summed over a set of indexed terms in a formula, thus exerting notational brevity. Arnold Sommerfeld would create the contour integral sign in 1917. Also in 1917, Dimitry Mirimanoff proposes axiom of regularity. In 1919, Theodor Kaluza would solve general relativity equations using five dimensions, the results would have electromagnetic equations emerge. This would be published in 1921 in "Zum Unitätsproblem der Physik". In 1922, Abraham Fraenkel and Thoralf Skolem independently proposed replacing the axiom schema of specification with the axiom schema of replacement. Also in 1922, Zermelo–Fraenkel set theory was developed. In 1923, Steinmetz would publish Four Lectures on Relativity and Space. Around 1924, Jan Arnoldus Schouten would develop the modern notation and formalism for the Ricci calculus framework during the absolute differential calculus applications to general relativity and differential geometry in the early twentieth century. In 1925, Enrico Fermi would describe a system comprising many identical particles that obey the Pauli exclusion principle, afterwards developing a diffusion equation (Fermi age equation). In 1926, Oskar Klein would develop the Kaluza–Klein theory. In 1928, Emil Artin abstracted ring theory with Artinian rings. In 1933, Andrey Kolmogorov introduces the Kolmogorov axioms. In 1937, Bruno de Finetti deduced the "operational subjective" concept.

Mathematical symbolism

Mathematical abstraction began as a process of extracting the underlying essence of a mathematical concept, removing any dependence on real world objects with which it might originally have been connected, and generalizing it so that it has wider applications or matching among other abstract descriptions of equivalent phenomena. Two abstract areas of modern mathematics are category theory and model theory. Bertrand Russell, said, "Ordinary language is totally unsuited for expressing what physics really asserts, since the words of everyday life are not sufficiently abstract. Only mathematics and mathematical logic can say as little as the physicist means to say". Though, one can substituted mathematics for real world objects, and wander off through equation after equation, and can build a concept structure which has no relation to reality.

Symbolic logic studies the purely formal properties of strings of symbols. The interest in this area springs from two sources. First, the notation used in symbolic logic can be seen as representing the words used in philosophical logic. Second, the rules for manipulating symbols found in symbolic logic can be implemented on a computing machine. Symbolic logic is usually divided into two subfields, propositional logic and predicate logic. Other logics of interest include temporal logic, modal logic and fuzzy logic. The area of symbolic logic called propositional logic, also called propositional calculus, studies the properties of sentences formed from constants and logical operators. The corresponding logical operations are known, respectively, as conjunction, disjunction, material conditional, biconditional, and negation. These operators are denoted as keywords and by symbolic notation.

Some of the introduced mathematical logic notation during this time included the set of symbols used in Boolean algebra. This was created by George Boole in 1854. Boole himself did not see logic as a branch of mathematics, but it has come to be encompassed anyway. Symbols found in Boolean algebra include (AND), (OR), and (not). With these symbols, and letters to represent different truth values, one can make logical statements such as , that is "(a is true OR a is not true) is true", meaning it is true that a is either true or not true (i.e. false). Boolean algebra has many practical uses as it is, but it also was the start of what would be a large set of symbols to be used in logic. Predicate logic, originally called predicate calculus, expands on propositional logic by the introduction of variables and by sentences containing variables, called predicates. In addition, predicate logic allows quantifiers. With these logic symbols and additional quantifiers from predicate logic, valid proofs can be made that are irrationally artificial, but syntactical.

Gödel incompleteness notation

To every ω-consistent recursive class κ of formulae there correspond recursive class signs r, such that neither v Gen r nor Neg (v Gen r) belongs to Flg (κ) (where v is the free variable of r).

— Kurt Gödel

While proving his incompleteness theorems, Kurt Gödel created an alternative to the symbols normally used in logic. He used Gödel numbers, which were numbers that represented operations with set numbers, and variables with the prime numbers greater than 10. With Gödel numbers, logic statements can be broken down into a number sequence. Gödel then took this one step farther, taking the n prime numbers and putting them to the power of the numbers in the sequence. These numbers were then multiplied together to get the final product, giving every logic statement its own number.

Contemporary notation and topics

Early 20th-century notation

Abstraction of notation is an ongoing process and the historical development of many mathematical topics exhibits a progression from the concrete to the abstract. Various set notations would be developed for fundamental object sets. Around 1924, David Hilbert and Richard Courant published "Methods of mathematical physics. Partial differential equations". In 1926, Oskar Klein and Walter Gordon proposed the Klein–Gordon equation to describe relativistic particles. The first formulation of a quantum theory describing radiation and matter interaction is due to Paul Adrien Maurice Dirac, who, during 1920, was first able to compute the coefficient of spontaneous emission of an atom. In 1928, the relativistic Dirac equation was formulated by Dirac to explain the behavior of the relativistically moving electron. Dirac described the quantification of the electromagnetic field as an ensemble of harmonic oscillators with the introduction of the concept of creation and annihilation operators of particles. In the following years, with contributions from Wolfgang Pauli, Eugene Wigner, Pascual Jordan, and Werner Heisenberg, and an elegant formulation of quantum electrodynamics due to Enrico Fermi, physicists came to believe that, in principle, it would be possible to perform any computation for any physical process involving photons and charged particles.

In 1931, Alexandru Proca developed the Proca equation (Euler–Lagrange equation) for the vector meson theory of nuclear forces and the relativistic quantum field equations. John Archibald Wheeler in 1937 develops S-matrix. Studies by Felix Bloch with Arnold Nordsieck, and Victor Weisskopf, in 1937 and 1939, revealed that such computations were reliable only at a first order of perturbation theory, a problem already pointed out by Robert Oppenheimer. At higher orders in the series infinities emerged, making such computations meaningless and casting serious doubts on the internal consistency of the theory itself. With no solution for this problem known at the time, it appeared that a fundamental incompatibility existed between special relativity and quantum mechanics.

In the 1930s, the double-struck capital Z for integer number sets was created by Edmund Landau. Nicolas Bourbaki created the double-struck capital Q for rational number sets. In 1935, Gerhard Gentzen made universal quantifiers. In 1936, Tarski's undefinability theorem is stated by Alfred Tarski and proved. In 1938, Gödel proposes the constructible universe in the paper "The Consistency of the Axiom of Choice and of the Generalized Continuum-Hypothesis". André Weil and Nicolas Bourbaki would develop the empty set sign in 1939. That same year, Nathan Jacobson would coin the double-struck capital C for complex number sets.

Around the 1930s, Voigt notation would be developed for multilinear algebra as a way to represent a symmetric tensor by reducing its order. Schönflies notation became one of two conventions used to describe point groups (the other being Hermann–Mauguin notation). Also in this time, van der Waerden notation became popular for the usage of two-component spinors (Weyl spinors) in four spacetime dimensions. Arend Heyting would introduce Heyting algebra and Heyting arithmetic.

The arrow, e.g., →, was developed for function notation in 1936 by Øystein Ore to denote images of specific elements. Later, in 1940, it took its present form, e.g., f: X → Y, through the work of Witold Hurewicz. Werner Heisenberg, in 1941, proposed the S-matrix theory of particle interactions.

Bra–ket notation (Dirac notation) is a standard notation for describing quantum states, composed of angle brackets and vertical bars. It can also be used to denote abstract vectors and linear functionals. It is so called because the inner product (or dot product on a complex vector space) of two states is denoted by a ⟨bra|ket⟩ consisting of a left part, ⟨φ|, and a right part, |ψ⟩. The notation was introduced in 1939 by Paul Dirac, though the notation has precursors in Grassmann's use of the notation [φ|ψ] for his inner products nearly 100 years previously.

Bra–ket notation is widespread in quantum mechanics: almost every phenomenon that is explained using quantum mechanics—including a large portion of modern physics—is usually explained with the help of bra–ket notation. The notation establishes an encoded abstract representation-independence, producing a versatile specific representation (e.g., x, or p, or eigenfunction base) without much ado, or excessive reliance on, the nature of the linear spaces involved. The overlap expression ⟨φ|ψ⟩ is typically interpreted as the probability amplitude for the state ψ to collapse into the state ϕ. The Feynman slash notation (Dirac slash notation) was developed by Richard Feynman for the study of Dirac fields in quantum field theory.

In 1948, Valentine Bargmann and Eugene Wigner proposed the relativistic Bargmann–Wigner equations to describe free particles and the equations are in the form of multi-component spinor field wavefunctions. In 1950, William Vallance Douglas Hodge presented "The topological invariants of algebraic varieties" at the Proceedings of the International Congress of Mathematicians. Between 1954 and 1957, Eugenio Calabi worked on the Calabi conjecture for Kähler metrics and the development of Calabi–Yau manifolds. In 1957, Tullio Regge formulated the mathematical property of potential scattering in the Schrödinger equation. Stanley Mandelstam, along with Regge, did the initial development of the Regge theory of strong interaction phenomenology. In 1958, Murray Gell-Mann and Richard Feynman, along with George Sudarshan and Robert Marshak, deduced the chiral structures of the weak interaction in physics. Geoffrey Chew, along with others, would promote matrix notation for the strong interaction, and the associated bootstrap principle, in 1960. In the 1960s, set-builder notation was developed for describing a set by stating the properties that its members must satisfy. Also in the 1960s, tensors are abstracted within category theory by means of the concept of monoidal category. Later, multi-index notation eliminates conventional notions used in multivariable calculus, partial differential equations, and the theory of distributions, by abstracting the concept of an integer index to an ordered tuple of indices.

Modern mathematical notation

In the modern mathematics of special relativity, electromagnetism and wave theory, the d'Alembert operator is the Laplace operator of Minkowski space. The Levi-Civita symbol is used in tensor calculus.

After the full Lorentz covariance formulations that were finite at any order in a perturbation series of quantum electrodynamics, Sin-Itiro Tomonaga, Julian Schwinger and Richard Feynman were jointly awarded with a Nobel prize in physics in 1965. Their contributions, and those of Freeman Dyson, were about covariant and gauge invariant formulations of quantum electrodynamics that allow computations of observables at any order of perturbation theory. Feynman's mathematical technique, based on his diagrams, initially seemed very different from the field-theoretic, operator-based approach of Schwinger and Tomonaga, but Freeman Dyson later showed that the two approaches were equivalent. Renormalization, the need to attach a physical meaning at certain divergences appearing in the theory through integrals, has subsequently become one of the fundamental aspects of quantum field theory and has come to be seen as a criterion for a theory's general acceptability. Quantum electrodynamics has served as the model and template for subsequent quantum field theories. Peter Higgs, Jeffrey Goldstone, and others, Sheldon Glashow, Steven Weinberg and Abdus Salam independently showed how the weak nuclear force and quantum electrodynamics could be merged into a single electroweak force. In the late 1960s, the particle zoo was composed of the then known elementary particles before the discovery of quarks.

The fundamental fermions and the fundamental bosons. (c.2008) Based on the proprietary publication, Review of Particle Physics.

A step towards the Standard Model was Sheldon Glashow's discovery, in 1960, of a way to combine the electromagnetic and weak interactions. In 1967, Steven Weinberg and Abdus Salam incorporated the Higgs mechanism into Glashow's electroweak theory, giving it its modern form. The Higgs mechanism is believed to give rise to the masses of all the elementary particles in the Standard Model. This includes the masses of the W and Z bosons, and the masses of the fermions – i.e. the quarks and leptons. Also in 1967, Bryce DeWitt published his equation under the name "Einstein–Schrödinger equation" (later renamed the "Wheeler–DeWitt equation"). In 1969, Yoichiro Nambu, Holger Bech Nielsen, and Leonard Susskind described space and time in terms of strings. In 1970, Pierre Ramond develop two-dimensional supersymmetries. Michio Kaku and Keiji Kikkawa would afterwards formulate string variations. In 1972, Michael Artin, Alexandre Grothendieck, Jean-Louis Verdier propose the Grothendieck universe.

After the neutral weak currents caused by

Z

boson exchange were discovered at CERN in 1973, the electroweak theory became widely accepted and Glashow, Salam, and Weinberg shared the 1979 Nobel Prize in Physics for discovering it. The theory of the strong interaction, to which many contributed, acquired its modern form around 1973–74. With the establishment of quantum chromodynamics, a finalized a set of fundamental and exchange particles, which allowed for the establishment of a "standard model" based on the mathematics of gauge invariance,

which successfully described all forces except for gravity, and which

remains generally accepted within the domain to which it is designed to

be applied. In the late 1970s, William Thurston introduced hyperbolic geometry into the study of knots with the hyperbolization theorem. The orbifold notation system, invented by Thurston, has been developed for representing types of symmetry groups in two-dimensional spaces of constant curvature. In 1978, Shing-Tung Yau deduced that the Calabi conjecture have Ricci flat metrics. In 1979, Daniel Friedan showed that the equations of motions of string theory are abstractions of Einstein equations of General Relativity.

The first superstring revolution is composed of mathematical equations developed between 1984 and 1986. In 1984, Vaughan Jones deduced the Jones polynomial and subsequent contributions from Edward Witten, Maxim Kontsevich, and others, revealed deep connections between knot theory and mathematical methods in statistical mechanics and quantum field theory. According to string theory, all particles in the "particle zoo" have a common ancestor, namely a vibrating string. In 1985, Philip Candelas, Gary Horowitz, Andrew Strominger, and Edward Witten would publish "Vacuum configurations for superstrings" Later, the tetrad formalism (tetrad index notation) would be introduced as an approach to general relativity that replaces the choice of a coordinate basis by the less restrictive choice of a local basis for the tangent bundle.

In the 1990s, Roger Penrose would propose Penrose graphical notation (tensor diagram notation) as a, usually handwritten, visual depiction of multilinear functions or tensors. Penrose would also introduce abstract index notation. In 1995, Edward Witten suggested M-theory and subsequently used it to explain some observed dualities, initiating the second superstring revolution.

John Conway would further various notations, including the Conway chained arrow notation, the Conway notation of knot theory, and the Conway polyhedron notation. The Coxeter notation system classifies symmetry groups, describing the angles between with fundamental reflections of a Coxeter group. It uses a bracketed notation, with modifiers to indicate certain subgroups. The notation is named after H. S. M. Coxeter and Norman Johnson more comprehensively defined it.

Combinatorial LCF notation has been developed for the representation of cubic graphs that are Hamiltonian. The cycle notation is the convention for writing down a permutation in terms of its constituent cycles. This is also called circular notation and the permutation called a cyclic or circular permutation.

Computers and markup notation

In 1931, IBM produces the IBM 601 Multiplying Punch; it is an electromechanical machine that could read two numbers, up to 8 digits long, from a card and punch their product onto the same card. In 1934, Wallace Eckert used a rigged IBM 601 Multiplying Punch to automate the integration of differential equations. In 1936, Alan Turing publishes "On Computable Numbers, With an Application to the Entscheidungsproblem". John von Neumann, pioneer of the digital computer and of computer science, in 1945, writes the incomplete First Draft of a Report on the EDVAC. In 1962, Kenneth E. Iverson developed an integral part notation, which became APL, for manipulating arrays that he taught to his students, and described in his book A Programming Language. In 1970, Edgar F. Codd proposed relational algebra as a relational model of data for database query languages. In 1971, Stephen Cook publishes "The complexity of theorem proving procedures" In the 1970s within computer architecture, Quote notation was developed for a representing number system of rational numbers. Also in this decade, the Z notation (just like the APL language, long before it) uses many non-ASCII symbols, the specification includes suggestions for rendering the Z notation symbols in ASCII and in LaTeX. There are presently various C mathematical functions (Math.h) and numerical libraries. They are libraries used in software development for performing numerical calculations. These calculations can be handled by symbolic executions; analyzing a program to determine what inputs cause each part of a program to execute. Mathematica and SymPy are examples of computational software programs based on symbolic mathematics.

Future of mathematical notation

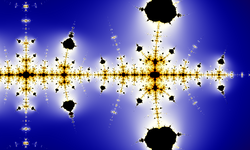

In the history of mathematical notation, ideographic symbol notation has come full circle with the rise of computer visualization systems. The notations can be applied to abstract visualizations, such as for rendering some projections of a Calabi–Yau manifold. Examples of abstract visualization which properly belong to the mathematical imagination can be found in computer graphics. The need for such models abounds, for example, when the measures for the subject of study are actually random variables and not really ordinary mathematical functions.