| Vagus nerve | |

|---|---|

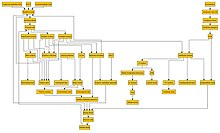

Plan of the upper portions of the glossopharyngeal, vagus, and accessory nerves. | |

Course and distribution of the glossopharyngeal, vagus, and accessory nerves. | |

| Details | |

| Innervates | Levator veli palatini, Salpingopharyngeus, Palatoglossus, Palatopharyngeus, Superior pharyngeal constrictor, Middle pharyngeal constrictor, Inferior pharyngeal constrictor, viscera |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | nervus vagus |

| MeSH | D014630 |

| NeuroNames | 702 |

| TA98 | A14.2.01.153 |

| TA2 | 6332 |

| FMA | 5731 |

| Anatomical terms of neuroanatomy | |

| Cranial nerves |

|---|

|

The vagus nerve, also known as the tenth cranial nerve, cranial nerve X, or simply CN X, is a cranial nerve that carries sensory fibers that create a pathway that interfaces with the parasympathetic control of the heart, lungs, and digestive tract. It comprises two nerves—the left and right vagus nerves—but they are typically referred to collectively as a single subsystem. The vagus is the longest nerve of the autonomic nervous system in the human body and comprises both sensory and motor fibers. The sensory fibers originate from neurons of the nodose ganglion, whereas the motor fibers come from neurons of the dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus and the nucleus ambiguus. The vagus was also historically called the pneumogastric nerve.

Structure

Upon leaving the medulla oblongata between the olive and the inferior cerebellar peduncle, the vagus nerve extends through the jugular foramen, then passes into the carotid sheath between the internal carotid artery and the internal jugular vein down to the neck, chest, and abdomen, where it contributes to the innervation of the viscera, reaching all the way to the colon. Besides giving some output to various organs, the vagus nerve comprises between 80% and 90% of afferent nerves mostly conveying sensory information about the state of the body's organs to the central nervous system. The right and left vagus nerves descend from the cranial vault through the jugular foramina, penetrating the carotid sheath between the internal and external carotid arteries, then passing posterolateral to the common carotid artery. The cell bodies of visceral afferent fibers of the vagus nerve are located bilaterally in the inferior ganglion of the vagus nerve (nodose ganglia).

The vagus runs parallel to the common carotid artery and internal jugular vein inside the carotid sheath

The right vagus nerve gives rise to the right recurrent laryngeal nerve, which hooks around the right subclavian artery and ascends into the neck between the trachea and esophagus. The right vagus then crosses anterior to the right subclavian artery, runs posterior to the superior vena cava, descends posterior to the right main bronchus, and contributes to cardiac, pulmonary, and esophageal plexuses. It forms the posterior vagal trunk at the lower part of the esophagus and enters the diaphragm through the esophageal hiatus.

The left vagus nerve enters the thorax between left common carotid artery and left subclavian artery and descends on the aortic arch. It gives rise to the left recurrent laryngeal nerve, which hooks around the aortic arch to the left of the ligamentum arteriosum and ascends between the trachea and esophagus. The left vagus further gives off thoracic cardiac branches, breaks up into the pulmonary plexus, continues into the esophageal plexus, and enters the abdomen as the anterior vagal trunk in the esophageal hiatus of the diaphragm.

Branches

- Pharyngeal nerve

- Superior laryngeal nerve

- Aortic nerve

- Superior cervical cardiac branches of vagus nerve

- Inferior cervical cardiac branch

- Recurrent laryngeal nerve

- Thoracic cardiac branches

- Branches to the pulmonary plexus

- Branches to the esophageal plexus

- Anterior vagal trunk

- Posterior vagal trunk

- Hering–Breuer reflex in alveoli

.

Nuclei

The vagus nerve includes axons which emerge from or converge onto four nuclei of the medulla:

- The dorsal nucleus of vagus nerve – which sends parasympathetic output to the viscera, especially the intestines

- The nucleus ambiguus – which gives rise to the branchial efferent motor fibers of the vagus nerve and preganglionic parasympathetic neurons that innervate the heart

- The solitary nucleus – which receives afferent taste information and primary afferents from visceral organs

- The spinal trigeminal nucleus – which receives information about deep/crude touch, pain, and temperature of the outer ear, the dura of the posterior cranial fossa and the mucosa of the larynx

Development

The motor division of the glossopharyngeal nerve is derived from the basal plate of the embryonic medulla oblongata, while the sensory division originates from the cranial neural crest.

Function

The vagus nerve supplies motor parasympathetic fibers to all the organs (except the adrenal glands), from the neck down to the second segment of the transverse colon. The vagus also controls a few skeletal muscles, including:

- Cricothyroid muscle

- Levator veli palatini muscle

- Salpingopharyngeus muscle

- Palatoglossus muscle

- Palatopharyngeus muscle

- Superior, middle and inferior pharyngeal constrictors

- Muscles of the larynx (speech).

This means that the vagus nerve is responsible for such varied tasks as heart rate, gastrointestinal peristalsis, sweating, and quite a few muscle movements in the mouth, including speech (via the recurrent laryngeal nerve). It also has some afferent fibers that innervate the inner (canal) portion of the outer ear (via the auricular branch, also known as Arnold's or Alderman's nerve) and part of the meninges.

Efferent vagus nerve fibers innervating the pharynx and back of the throat are responsible for the gag reflex. In addition, 5-HT3 receptor-mediated afferent vagus stimulation in the gut due to gastroenteritis is a cause of vomiting. Stimulation of the vagus nerve in the cervix uteri (as in some medical procedures) can lead to a vasovagal response.

The vagus nerve also plays a role in satiation following food consumption. Knocking out vagal nerve receptors has been shown to cause hyperphagia (greatly increased food intake).

Cardiac effects

Parasympathetic innervation of the heart is partially controlled by the vagus nerve and is shared by the thoracic ganglia. Vagal and spinal ganglionic nerves mediate the lowering of the heart rate. The right vagus branch innervates the sinoatrial node. In healthy people, parasympathetic tone from these sources is well-matched to sympathetic tone. Hyperstimulation of parasympathetic influence promotes bradyarrhythmias. When hyperstimulated, the left vagal branch predisposes the heart to conduction block at the atrioventricular node.

At this location, neuroscientist Otto Loewi first demonstrated that nerves secrete substances called neurotransmitters, which have effects on receptors in target tissues. In his experiment, Loewi electrically stimulated the vagus nerve of a frog heart, which slowed the heart. Then he took the fluid from the heart and transferred it to a second frog heart without a vagus nerve. The second heart slowed without electrical stimulation. Loewi described the substance released by the vagus nerve as vagusstoff, which was later found to be acetylcholine. Drugs that inhibit the muscarinic receptors (anticholinergics) such as atropine and scopolamine, are called vagolytic because they inhibit the action of the vagus nerve on the heart, gastrointestinal tract, and other organs. Anticholinergic drugs increase heart rate and are used to treat bradycardia.

Urogenital and hormonal effects

Excessive activation of the vagal nerve during emotional stress, which is a parasympathetic overcompensation for a strong sympathetic nervous system response associated with stress, can also cause vasovagal syncope due to a sudden drop in cardiac output, causing cerebral hypoperfusion. Vasovagal syncope affects young children and women more than other groups. It can also lead to temporary loss of bladder control under moments of extreme fear.

Research has shown that women having had complete spinal cord injury can experience orgasms through the vagus nerve, which can go from the uterus and cervix to the brain.

Insulin signaling activates the adenosine triphosphate (ATP)-sensitive potassium (KATP) channels in the arcuate nucleus, decreases AgRP release, and through the vagus nerve, leads to decreased glucose production by the liver by decreasing gluconeogenic enzymes: phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase, glucose 6-phosphatase.

Clinical significance

Stimulation

Vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) therapy via a neurostimulator implanted in the chest has been used to control seizures in epilepsy patients and has been approved for treating drug-resistant clinical depression. A noninvasive VNS device that stimulates an afferent branch of the vagus nerve is being developed and will soon undergo trials.

Clinical trials have started in Antwerp, Belgium, using VNS for the treatment of tonal tinnitus after a study published in early 2011 by researchers at the University of Texas at Dallas showed successful tinnitus suppression in rats when tones were paired with brief pulses of stimulation of the vagus nerve.

VNS may also be achieved by one of the vagal maneuvers: holding the breath for 20 to 60 seconds, dipping the face in cold water, coughing, humming or singing, or tensing the stomach muscles as if to bear down to have a bowel movement. Patients with supraventricular tachycardia, atrial fibrillation, and other illnesses may be trained to perform vagal maneuvers (or find one or more on their own).

Vagus nerve blocking (VBLOC) therapy is similar to VNS but used only during the day. In a six-month open-label trial involving three medical centers in Australia, Mexico, and Norway, vagus nerve blocking helped 31 obese participants lose an average of nearly 15 percent of their excess weight. As of 2008, a yearlong double-blind, phase II trial had begun.

Vagotomy

Vagotomy (cutting of the vagus nerve) is a now obsolete therapy that was performed for peptic ulcer disease and now superseded by oral medications, including H2 antagonists, proton pump inhibitors and antibiotics. Vagotomy is currently being researched as a less invasive alternative weight-loss procedure to gastric bypass surgery. The procedure curbs the feeling of hunger and is sometimes performed in conjunction with putting bands on patients' stomachs, resulting in an average of 43% of excess weight loss at six months with diet and exercise.

One serious side effect of vagotomy is a vitamin B12 deficiency later in life – perhaps after about 10 years – that is similar to pernicious anemia. The vagus normally stimulates the stomach's parietal cells to secrete acid and intrinsic factor. Intrinsic factor is needed to absorb vitamin B12 from food. The vagotomy reduces this secretion and ultimately leads to deficiency, which, if left untreated, causes nerve damage, tiredness, dementia, paranoia, and ultimately death.

Researchers from Aarhus University and Aarhus University Hospital have demonstrated that vagotomy prevents (halves the risk of) the development of Parkinson's disease, suggesting that Parkinson's disease begins in the gastrointestinal tract and spreads via the vagus nerve to the brain. Or giving further evidence to the theory that dysregulated environmental stimuli, such as that received by the vagus nerve from the gut, may have a negative effect on the dopamine reward system of the substantia nigra, thereby causing Parkinson's disease.

Vagus Nerve Pathology

The sympathetic and parasympathetic components of the autonomic nervous system (ANS) control and regulate the function of various organs, glands, and involuntary muscles throughout the body (e.g., vocalization, swallowing, heart rate, respiration, gastric secretion, and intestinal motility). Hence, most of the signs and symptoms of vagus nerve dysfunction, apart from vocalisation, are vague and non specific. Laryngeal nerve palsy result in paralysis of an ipsilateral vocal cord and is use as a pointer to diseases affecting the vagus nerve from its origin down to termination of its branch of the laryngeal nerve.

- Sensory neuropathy

The hypersensitivity of vagal afferent nerves causes refractory or idiopathic cough.

Arnold's nerve ear-cough reflex, though uncommon, is a manifestation of a vagal sensory neuropathy and this is the cause of a refractory chronic cough that can be treated with gabapentin. The cough is triggered by mechanical stimulation of the external auditory meatus and accompanied by other neuropathic features such as throat irritation (laryngeal paresthesia) and cough triggered by exposure to nontussive triggers such as cold air and eating (termed allotussia). These features suggest a neuropathic origin to the cough.

- motor neuropathy

Pathology of the vagus nerve proximal to the laryngeal nerve typically presents with symptom hoarse voice and physical sign of paralysed vocal cords. Although a large proportion of these are the result of idiopathic vocal cord palsy but tumours especially lung cancers are next common cause. Tumours at the apex of right lung and at the hilum of the left lung are the most common oncology causes of vocal cord palsy. Less common tumours causing vocal cord palsy includes thyroid and proximal oesophageal malignancy.