The philosophy of war is the area of philosophy devoted to examining issues such as the causes of war, the relationship between war and human nature, and the ethics of war. Certain aspects of the philosophy of war overlap with the philosophy of history, political philosophy, international relations and the philosophy of law.

Works about the philosophy of war

Perhaps the greatest and most influential work in the philosophy of war is Carl von Clausewitz's On War, published in 1832. It combines observations on strategy with questions about human nature and the purpose of war. Clausewitz especially examines the teleology of war: whether war is a means to an end outside itself or whether it can be an end in itself. He concludes that the latter cannot be so, and that war is "politics by different means"; i.e. that war must not exist only for its own sake. It must serve some purpose for the state.

Leo Tolstoy's 1869 novel War and Peace contains frequent philosophical digressions on the philosophy of war (and broader metaphysical speculations derived from Christianity and from Tolstoy's observations of the Napoleonic Wars). It was influential on later thought about war. Tolstoy's Christian-centered philosophy of war (especially his essays "A Letter to a Hindu" (1908) and "The Kingdom of God is Within You" (1894)) directly influenced Gandhi's Hinduism-centered non-violent resistance philosophy.

Writing in 1869, Genrikh Leer emphasized the favorable effects of war on nations: "[...] war emerges as a powerful tool in the matter of improving the internal, moral and material life of peoples [...]."[1]

While Sun Tzu's The Art of War (5th century BCE), focuses mostly on weaponry and strategy instead of on philosophy, various commentators have broadened his observations into philosophies applied in situations extending well beyond war itself such as competition or management (see the main Wikipedia article on The Art of War for a discussion of the application of Sun Tzu's philosophy to areas other than war). In the early 16th century, parts of Niccolò Machiavelli's masterpiece The Prince (as well as his Discourses) and parts of Machiavelli's own work titled The Art of War discuss some philosophical points relating to war, though neither book could be said to be a work in the philosophy of war.

Just War Theory

The Indian Hindu epic, the Mahabharata, offers the first written discussions of a "just war" (dharma-yuddha or "righteous war"). In it, one of five ruling brothers (Pandavas) asks if the suffering caused by war can ever be justified. A long discussion then ensues between the siblings, establishing criteria like proportionality (chariots cannot attack cavalry, only other chariots; no attacking people in distress), just means (no poisoned or barbed arrows), just cause (no attacking out of rage), and fair treatment of captives and the wounded. The philosophy of just war theorizes what aspects of war are justifiable according to morally acceptable principles. Just war theory is based upon four core criteria to be followed by those determined to go to war. The four principles are as follows: just authority; just cause; right intention; last resort.

Just authority

The criterion of just authority refers to the determined legality of going to war, and whether the concept of war and the pursuit of it has been legally processed and justified.

Just cause

Just cause is a justifiable reason that war is the appropriate and necessary response. If war can be avoided, that must be determined first, according to the philosophy of just war theory.

Right intention

To go to war, one must determine if the intentions of doing so are right according to morality. Right intention criterion requires the determination of whether or not a war response is a measurable way to the conflict being acted upon.

Last resort

War is a last resort response, meaning that if there is a conflict between disagreeing parties, all solutions must be attempted before resorting to war.

Traditions of thought

Since the philosophy of war is often treated as a subset of another branch of philosophy (for example, political philosophy or the philosophy of law) it would be difficult to define any clear-cut schools of thought in the same sense that, e.g., Existentialism or Objectivism can be described as distinct movements. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy refers to Carl von Clausewitz as "the only (so-called) philosopher of war", implying that he is the only (major) philosophical writer who develops a philosophical system focusing exclusively on war. However, discernible traditions of thought on war have developed over time, so that some writers have been able to distinguish broad categories (if somewhat loosely).

Teleological categories

Anatol Rapoport's introduction to his edition of the J. J. Graham translation of Clausewitz's On War identifies three main teleological traditions in the philosophy of war: the cataclysmic, the eschatological, and the political. (On War, Rapoport's introduction, 13). These are not the only possible teleological philosophies of war, but only three of the most common. As Rapoport says,

To put it metaphorically, in political philosophy war is compared to a game of strategy (like chess); in eschatological philosophy, to a mission or the dénouement of a drama; in cataclysmic philosophy, to a fire or an epidemic.

These do not, of course, exhaust the views of war prevailing at different times and at different places. For example, war has at times been viewed as a pastime or an adventure, as the only proper occupation for a nobleman, as an affair of honor (for example, the days of chivalry), as a ceremony (e.g. among the Aztecs), as an outlet of aggressive instincts or a manifestation of a "death wish", as nature's way of ensuring the survival of the fittest, as an absurdity (e.g. among Eskimos), as a tenacious custom, destined to die out like slavery, and as a crime. (On War, Rapoport's introduction, 17)

- The Cataclysmic school of thought, which was espoused by Leo Tolstoy in his epic novel War and Peace, sees war as a bane on humanity – whether avoidable or inevitable – which serves little purpose outside of causing destruction and suffering, and which may cause drastic change to society, but not in any teleological sense. Tolstoy's view may be placed under the subcategory of global cataclysmic philosophy of war. Another subcategory of the cataclysmic school of thought is the ethnocentric cataclysmic, in which this view is focused specifically on the plight of a specific ethnicity or nation, for example the view in Judaism of war as a punishment from God on the Israelites in certain books of the Tenakh (Old Testament). As the Tenakh (in certain books) sees war as an ineluctable act of God, so Tolstoy especially emphasizes war as something that befalls man and is in no way under the influence of man's "free will", but is instead the result of irresistible global forces. (On War, Rapoport's introduction 16)

- The Eschatological school of thought sees all wars (or all major wars) as leading to some goal, and asserts that some final conflict will someday resolve the path followed by all wars and result in a massive upheaval of society and a subsequent new society free from war (in varying theories the resulting society may be either a utopia or a dystopia). There are two subsets of this view: the Messianic and the Global theory. The Marxist concept of a communist world ruled by the proletariat after a final worldwide revolution is an example of the global theory, and the Christian concept of an Armageddon war which will usher in the second coming of Christ and the final defeat of Satan is an example of a theory that could fall under Global or Messianic. (On War, Rapoport's introduction, 15) The messianic eschatological philosophy is derived from the Jewish-Christian concept of a Messiah, and sees wars as culminating in unification of humanity under a single faith or a single ruler. Crusades, Jihads, the Nazi concept of a Master Race and the 19th century American concept of Manifest Destiny may also fall under this heading. (On War, Rapoport's introduction, 15) (See main articles for more information: Christian eschatology, Jewish eschatology)

- The Political school of thought, of which Clausewitz was a proponent, sees war as a tool of the state. On page 13 Rapoport says,

Clausewitz views war as a rational instrument of national policy. The three words "rational", "instrument" and "national" are the key concepts of his paradigm. In this view, the decision to wage war "ought" to be rational, in the sense that it ought to be based on estimated costs and gains of war. Next, war "ought" to be instrumental, in the sense that it ought to be waged in order to achieve some goal, never for its own sake; and also in the sense that strategy and tactics ought to be directed towards just one end, namely towards victory. Finally, war "ought" to be national, in the sense that its objective should be to advance the interests of a national state and that the entire effort of the nation ought to be mobilized in the service of the military objective.

- He later characterizes the philosophy behind the Vietnam War and other Cold War conflicts as "Neo-Clausewitzian". Rapoport also includes Machiavelli as an early example of the political philosophy of war (On War, Rapoport's introduction, 13). Decades after his essay, the War on Terrorism and the Iraq War begun by the United States under President George W. Bush in 2001 and 2003 have often been justified under the doctrine of preemption, a political motivation stating that the United States must use war to prevent further attacks such as the September 11, 2001 attacks.

Ethical categories

Another possible system for categorizing different schools of thought on war can be found in the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (see external links, below), based on ethics. The SEP describes three major divisions in the ethics of war: the realist, the pacifist, and the just war Theory. In a nutshell:

- Realists will typically hold that systems of morals and ethics which guide individuals within societies cannot realistically be applied to societies as a whole to govern the way they, as societies, interact with other societies. Hence, a state's purposes in war is simply to preserve its national interest. This kind of thinking is similar to Machiavelli's philosophy, and Thucydides and Hobbes may also fall under this category.

- Pacifism however, maintains that a moral evaluation of war is possible, and that war is always found to be immoral. Generally, there are two kinds of modern secular pacifism to consider: (1) a more consequentialist form of pacifism (or CP), which maintains that the benefits accruing from war can never outweigh the costs of fighting it; and (2) a more deontological form of pacifism (or DP), which contends that the very activity of war is intrinsically wrong, since it violates foremost duties of justice, such as not killing human beings. Eugene Victor Debs and others were famous advocates of pacifistic diplomatic methods instead of war.

- Just war theory, along with pacifism, holds that morals do apply to war. However, unlike pacifism, according to just war theory it is possible for a war to be morally justified. The concept of a morally justified war underlies much of the concept international law, such as the Geneva Conventions. Aristotle, Cicero, Augustine, Aquinas, and Hugo Grotius are among the philosophers who have espoused some form of a just war philosophy. One common just war theory evaluation of war is that war is only justified if 1.) waged in a state or nation's self-defense, or 2.) waged in order to end gross violations of human rights. Political philosopher John Rawls advocated these criteria as justification for war.

![The sphere of plutonium surrounded by neutron-reflecting tungsten carbide blocks in a re-enactment of Harry Daghlian's 1945 experiment.[35]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/1/13/Partially-reflected-plutonium-sphere.jpeg/120px-Partially-reflected-plutonium-sphere.jpeg)

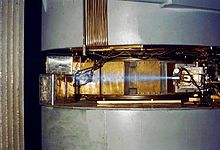

![Image of the Lady Godiva assembly in the scrammed (safe) configuration.[36]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2a/Godiva-before-scrammed.jpg/96px-Godiva-before-scrammed.jpg)

![Image of the Lady Godiva assembly, showing the damage caused to the supporting rods after the excursion of February 1954. Note the images are of different assemblies.[36]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/2a/Godiva-after-scrammed.jpg/99px-Godiva-after-scrammed.jpg)