Reproduction (or procreation or breeding) is the biological process by which new individual organisms – "offspring" – are produced from their "parent" or parents. Reproduction is a fundamental feature of all known life; each individual organism exists as the result of reproduction. There are two forms of reproduction: asexual and sexual.

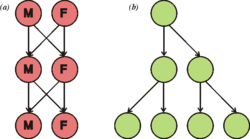

In asexual reproduction, an organism can reproduce without the involvement of another organism. Asexual reproduction is not limited to single-celled organisms. The cloning of an organism is a form of asexual reproduction. By asexual reproduction, an organism creates a genetically similar or identical copy of itself. The evolution of sexual reproduction is a major puzzle for biologists. The two-fold cost of sexual reproduction is that only 50% of organisms reproduce and organisms only pass on 50% of their genes.

Sexual reproduction typically requires the sexual interaction of two specialized reproductive cells, called gametes, which contain half the number of chromosomes of normal cells and are created by meiosis, with typically a male fertilizing a female of the same species to create a fertilized zygote. This produces offspring organisms whose genetic characteristics are derived from those of the two parental organisms.

Asexual

Asexual reproduction is a process by which organisms create genetically similar or identical copies of themselves without the contribution of genetic material from another organism. Bacteria divide asexually via binary fission; viruses take control of host cells to produce more viruses; Hydras (invertebrates of the order Hydroidea) and yeasts are able to reproduce by budding. These organisms often do not possess different sexes, and they are capable of "splitting" themselves into two or more copies of themselves. Most plants have the ability to reproduce asexually and the ant species Mycocepurus smithii is thought to reproduce entirely by asexual means.

Some species that are capable of reproducing asexually, like hydra, yeast (See Mating of yeasts) and jellyfish, may also reproduce sexually. For instance, most plants are capable of vegetative reproduction – reproduction without seeds or spores – but can also reproduce sexually. Likewise, bacteria may exchange genetic information by conjugation.

Other ways of asexual reproduction include parthenogenesis, fragmentation and spore formation that involves only mitosis. Parthenogenesis is the growth and development of embryo or seed without fertilization. Parthenogenesis occurs naturally in some species, including lower plants (where it is called apomixis), invertebrates (e.g. water fleas, aphids, some bees and parasitic wasps), and vertebrates (e.g. some reptiles, some fish, and very rarely, domestic birds).

Sexual

Sexual reproduction is a biological process that creates a new organism by combining the genetic material of two organisms in a process that starts with meiosis, a specialized type of cell division. Each of two parent organisms contributes half of the offspring's genetic makeup by creating haploid gametes. Most organisms form two different types of gametes. In these anisogamous species, the two sexes are referred to as male (producing sperm or microspores) and female (producing ova or megaspores). In isogamous species, the gametes are similar or identical in form (isogametes), but may have separable properties and then may be given other different names (see isogamy). Because both gametes look alike, they generally cannot be classified as male or female. For example, in the green alga, Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, there are so-called "plus" and "minus" gametes. A few types of organisms, such as many fungi and the ciliate Paramecium aurelia, have more than two "sexes", called mating types. Most animals (including humans) and plants reproduce sexually. Sexually reproducing organisms have different sets of genes for every trait (called alleles). Offspring inherit one allele for each trait from each parent. Thus, offspring have a combination of the parents' genes. It is believed that "the masking of deleterious alleles favors the evolution of a dominant diploid phase in organisms that alternate between haploid and diploid phases" where recombination occurs freely.

Bryophytes reproduce sexually, but the larger and commonly-seen organisms are haploid and produce gametes. The gametes fuse to form a zygote which develops into a sporangium, which in turn produces haploid spores. The diploid stage is relatively small and short-lived compared to the haploid stage, i.e. haploid dominance. The advantage of diploidy, heterosis, only exists in the diploid life generation. Bryophytes retain sexual reproduction despite the fact that the haploid stage does not benefit from heterosis. This may be an indication that the sexual reproduction has advantages other than heterosis, such as genetic recombination between members of the species, allowing the expression of a wider range of traits and thus making the population more able to survive environmental variation.

Allogamy

Allogamy is the fertilization of flowers through cross-pollination, this occurs when a flower's ovum is fertilized by spermatozoa from the pollen of a different plant's flower. Pollen may be transferred through pollen vectors or abiotic carriers such as wind. Fertilization begins when the pollen is brought to a female gamete through the pollen tube. Allogamy is also known as cross fertilization, in contrast to autogamy or geitonogamy which are methods of self-fertilization.

Autogamy

Self-fertilization, also known as autogamy, occurs in hermaphroditic organisms where the two gametes fused in fertilization come from the same individual, e.g., many vascular plants, some foraminiferans, some ciliates. The term "autogamy" is sometimes substituted for autogamous pollination (not necessarily leading to successful fertilization) and describes self-pollination within the same flower, distinguished from geitonogamous pollination, transfer of pollen to a different flower on the same flowering plant, or within a single monoecious Gymnosperm plant.

Mitosis and meiosis

Mitosis and meiosis are types of cell division. Mitosis occurs in somatic cells, while meiosis occurs in gametes.

Mitosis The resultant number of cells in mitosis is twice the number of original cells. The number of chromosomes in the offspring cells is the same as that of the parent cell.

Meiosis The resultant number of cells is four times the number of original cells. This results in cells with half the number of chromosomes present in the parent cell. A diploid cell duplicates itself, then undergoes two divisions (tetraploid to diploid to haploid), in the process forming four haploid cells. This process occurs in two phases, meiosis I and meiosis II.

Same-sex

Scientific research is currently investigating the possibility of same-sex procreation, which would produce offspring with equal genetic contributions from either two females or two males. The obvious approaches, subject to a growing amount of activity, are female sperm and male eggs. In 2004, by altering the function of a few genes involved with imprinting, other Japanese scientists combined two mouse eggs to produce daughter mice and in 2018 Chinese scientists created 29 female mice from two female mice mothers but were unable to produce viable offspring from two father mice. Researches noted that there is little chance these techniques would be applied to humans in the near future.

Strategies

There are a wide range of reproductive strategies employed by different species. Some animals, such as the human and northern gannet, do not reach sexual maturity for many years after birth and even then produce few offspring. Others reproduce quickly; but, under normal circumstances, most offspring do not survive to adulthood. For example, a rabbit (mature after 8 months) can produce 10–30 offspring per year, and a fruit fly (mature after 10–14 days) can produce up to 900 offspring per year. These two main strategies are known as K-selection (few offspring) and r-selection (many offspring). Which strategy is favoured by evolution depends on a variety of circumstances. Animals with few offspring can devote more resources to the nurturing and protection of each individual offspring, thus reducing the need for many offspring. On the other hand, animals with many offspring may devote fewer resources to each individual offspring; for these types of animals it is common for many offspring to die soon after birth, but enough individuals typically survive to maintain the population. Some organisms such as honey bees and fruit flies retain sperm in a process called sperm storage thereby increasing the duration of their fertility.

Other types

- Polycyclic animals reproduce intermittently throughout their lives.

- Semelparous organisms reproduce only once in their lifetime, such as annual plants (including all grain crops), and certain species of salmon, spider, bamboo and century plant. Often, they die shortly after reproduction. This is often associated with r-strategists.

- Iteroparous organisms produce offspring in successive (e.g. annual or seasonal) cycles, such as perennial plants. Iteroparous animals survive over multiple seasons (or periodic condition changes). This is more associated with K-strategists.

Asexual vs. sexual reproduction

Organisms that reproduce through asexual reproduction tend to grow in number exponentially. However, because they rely on mutation for variations in their DNA, all members of the species have similar vulnerabilities. Organisms that reproduce sexually yield a smaller number of offspring, but the large amount of variation in their genes makes them less susceptible to disease.

Many organisms can reproduce sexually as well as asexually. Aphids, slime molds, sea anemones, some species of starfish (by fragmentation), and many plants are examples. When environmental factors are favorable, asexual reproduction is employed to exploit suitable conditions for survival such as an abundant food supply, adequate shelter, favorable climate, disease, optimum pH or a proper mix of other lifestyle requirements. Populations of these organisms increase exponentially via asexual reproductive strategies to take full advantage of the rich supply resources.[24]

When food sources have been depleted, the climate becomes hostile, or individual survival is jeopardized by some other adverse change in living conditions, these organisms switch to sexual forms of reproduction. Sexual reproduction ensures a mixing of the gene pool of the species. The variations found in offspring of sexual reproduction allow some individuals to be better suited for survival and provide a mechanism for selective adaptation to occur. The meiosis stage of the sexual cycle also allows especially effective repair of DNA damages (see Meiosis). In addition, sexual reproduction usually results in the formation of a life stage that is able to endure the conditions that threaten the offspring of an asexual parent. Thus, seeds, spores, eggs, pupae, cysts or other "over-wintering" stages of sexual reproduction ensure the survival during unfavorable times and the organism can "wait out" adverse situations until a swing back to suitability occurs.

Life without

The existence of life without reproduction is the subject of some speculation. The biological study of how the origin of life produced reproducing organisms from non-reproducing elements is called abiogenesis. Whether or not there were several independent abiogenetic events, biologists believe that the last universal ancestor to all present life on Earth lived about 3.5 billion years ago.

Scientists have speculated about the possibility of creating life non-reproductively in the laboratory. Several scientists have succeeded in producing simple viruses from entirely non-living materials. However, viruses are often regarded as not alive. Being nothing more than a bit of RNA or DNA in a protein capsule, they have no metabolism and can only replicate with the assistance of a hijacked cell's metabolic machinery.

The production of a truly living organism (e.g. a simple bacterium) with no ancestors would be a much more complex task, but may well be possible to some degree according to current biological knowledge. A synthetic genome has been transferred into an existing bacterium where it replaced the native DNA, resulting in the artificial production of a new M. mycoides organism.

There is some debate within the scientific community over whether this cell can be considered completely synthetic on the grounds that the chemically synthesized genome was an almost 1:1 copy of a naturally occurring genome and, the recipient cell was a naturally occurring bacterium. The Craig Venter Institute maintains the term "synthetic bacterial cell" but they also clarify "...we do not consider this to be "creating life from scratch" but rather we are creating new life out of already existing life using synthetic DNA". Venter plans to patent his experimental cells, stating that "they are pretty clearly human inventions". Its creators suggests that building 'synthetic life' would allow researchers to learn about life by building it, rather than by tearing it apart. They also propose to stretch the boundaries between life and machines until the two overlap to yield "truly programmable organisms". Researchers involved stated that the creation of "true synthetic biochemical life" is relatively close in reach with current technology and cheap compared to the effort needed to place man on the Moon.