Human cannibalism is the act or practice of humans eating the flesh or internal organs of other human beings. A person who practices cannibalism is called a cannibal. The meaning of "cannibalism" has been extended into zoology to describe an individual of a species consuming all or part of another individual of the same species as food, including sexual cannibalism.

Neanderthals are believed to have practised cannibalism, and Neanderthals may have been eaten by anatomically modern humans. Cannibalism was also practised in ancient Egypt, Roman Egypt and during famines in Egypt such as the great famine of 1199–1202. The Island Carib people of the Lesser Antilles, from whom the word "cannibalism" is derived, acquired a long-standing reputation as cannibals after their legends were recorded in the 17th century. Some controversy exists over the accuracy of these legends and the prevalence of actual cannibalism in the culture.

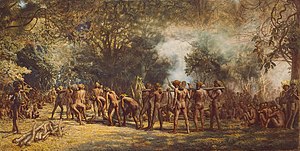

Cannibalism has been well documented in much of the world, including Fiji, the Amazon Basin, the Congo, and the Māori people of New Zealand. Cannibalism was also practised in New Guinea and in parts of the Solomon Islands, and human flesh was sold at markets in some parts of Melanesia. Fiji was once known as the "Cannibal Isles".

Cannibalism has recently been both practised and fiercely condemned in several wars, especially in Liberia and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It was still practised in Papua New Guinea as of 2012, for cultural reasons and in ritual as well as in war in various Melanesian tribes. Cannibalism has been said to test the bounds of cultural relativism because it challenges anthropologists "to define what is or is not beyond the pale of acceptable human behavior". Some scholars argue that no firm evidence exists that cannibalism has ever been a socially acceptable practice anywhere in the world, at any time in history, although this has been consistently debated against.

A form of cannibalism popular in early modern Europe was the consumption of body parts or blood for medical purposes. This practice was at its height during the 17th century, although as late as the second half of the 19th century some peasants attending an execution are recorded to have "rushed forward and scraped the ground with their hands that they might collect some of the bloody earth, which they subsequently crammed in their mouth, in hope that they might thus get rid of their disease."

Cannibalism has occasionally been practised as a last resort by people suffering from famine, even in modern times. Famous examples include the ill-fated Donner Party (1846–1847) and, more recently, the crash of Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571 (1972), after which some survivors ate the bodies of the dead. Additionally, there are cases of people engaging in cannibalism for sexual pleasure, such as Jeffrey Dahmer, Armin Meiwes, Issei Sagawa, and Albert Fish. There is resistance to formally labelling cannibalism a mental disorder.

Etymology

The word "cannibal" is derived from Spanish caníbal or caríbal, originally used as name for the Caribs, a people from the West Indies said to have eaten human flesh. The older term anthropophagy, meaning "eating humans", is also used for human cannibalism.

Reasons and types

Cannibalism has been practised under a variety of circumstances and for various motives. To adequately expression this diversity, Shirley Lindenbaum suggests that "it might be better to talk about 'cannibalisms'" in the plural.

Institutionalized, survival, and pathological cannibalism

One major distinction is whether cannibal acts are accepted by the culture in which they occur – institutionalized cannibalism – or whether they are merely practised under starvation conditions to ensure one's immediately survival – survival cannibalism – or by isolated individuals considered criminal and often pathological by society at large – cannibalism as psychopathology or "aberrant behavior".

Institutionalized cannibalism, sometimes also called "learned cannibalism", is the consumption of human body parts as "an institutionalized practice" generally accepted in the culture where it occurs.

By contrast, survival cannibalism means "the consumption of others under conditions of starvation such as shipwreck, military siege, and famine, in which persons normally averse to the idea are driven [to it] by the will to live". Such forms of cannibalism resorted to only in situations of extreme necessity have occur in many cultures where cannibalism is otherwise clearly rejected. The survivors of the shipwrecks of the Essex and Méduse in the 19th century are said to have engaged in cannibalism, as did the members of Franklin's lost expedition and the Donner Party. Such cases generally involve necro-cannibalism (eating the corpse of someone who is already dead) as opposed to homicidal cannibalism (killing someone for food). In English law, the latter is always considered a crime, even in the most trying circumstances. The case of R v Dudley and Stephens, in which two men were found guilty of murder for killing and eating a cabin boy while adrift at sea in a lifeboat, set the precedent that necessity is no defence to a charge of murder.

In other cases, cannibalism is an expression of a psychopathology or mental disorder, condemned by the society in which it occurs and "considered to be an indicator of [a] severe personality disorder or psychosis". Well-known cases include Albert Fish, Issei Sagawa, and Armin Meiwes.

Exo-, endo-, and autocannibalism

Within institutionalized cannibalism, exocannibalism is often distinguished from endocannibalism. Endocannibalism refers to the consumption of a person from the same community. Often it is a part of a funerary ceremony, similar to burial or cremation in other cultures. The consumption of the recently deceased in such rites can be considered "an act of affection" and a major part of the grieving process. It has also been explained as a way of guiding the souls of the dead into the bodies of living descendants.

In contrast, exocannibalism is the consumption of a person from outside the community. It is frequently "an act of aggression, often in the context of warfare", where the flesh of killed or captured enemies may be eaten to celebrate one's victory over them.

Both types of cannibalism can also be fuelled by the belief that eating a person's flesh or internal organs will endow the cannibal with some of the characteristics of the deceased. However, several authors investigating exocannibalism in New Zealand, New Guinea, and the Congo Basin observe that such believes were absent in these regions.

A further type, different from both exo- and endocannibalism, is autocannibalism (also called autophagy or self-cannibalism), "the act of eating parts of oneself". It does not ever seem to have been an institutionalized practice, but occasionally occurs as pathological behaviour, or due to other reasons such as curiosity. Also on record are instances of forced autocannibalism committed as acts of aggression, where individuals are forced to eat parts of their own bodies as a form of torture.

Additional motives and explanations

While exocannibalism is often associated with the consumption of enemies as an act of aggression and endocannibalism is often associated with the consumption of deceased relatives as a funerary rite and an act of affection, acts of institutionalized cannibalism can also be driven by other motives, for which additional names have been coined.

Medicinal cannibalism (also called medical cannibalism) means "the ingestion of human tissue ... as a supposed medicine or tonic". In contrast to other forms of cannibalism, which Europeans generally frowned upon, the "medicinal ingestion" of various "human body parts was widely practiced throughout Europe from the sixteenth to the eighteenth centuries", with early records of the practice going back to the first century CE. It was also frequently practised in China.

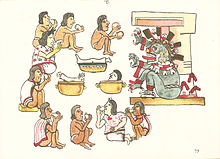

Sacrificial cannibalism refers the consumption of the flesh of victims of human sacrifice, for example among the Aztecs. Human and animal remains excavated in Knossos, Crete, have been interpreted as evidence of a ritual in which children and sheep were sacrificed and then eaten together during the Bronze Age. According to Ancient Roman reports the Celts in Britain practised sacrificial cannibalism, and archaeological evidence backing these claims has by now been found.

In Guns, Germs and Steel, Jared Diamond suggests "Protein starvation is probably also the ultimate reason why cannibalism was widespread in traditional New Guinea highland societies".

While not a motive, the term innocent cannibalism has been suggested for cases of people eating human flesh without knowing what they are eating. It is a subject of myths, such as the myth of Thyestes who unknowingly ate the flesh of his own sons. There are also actual cases on record, for example from the Congo Basin, where cannibalism had been quite widespread and where even in the 1950s travellers were sometimes served a meat dish, learning only afterwards that the meat had been of human origin.

In pre-modern medicine, the explanation given by the now-discredited theory of humorism for cannibalism was that it came about within a black acrimonious humour, which, being lodged in the linings of the ventricle, produced the voracity for human flesh.

Medical aspects

A well-known case of mortuary cannibalism is that of the Fore tribe in New Guinea, which resulted in the spread of the prion disease kuru. Although the Fore's mortuary cannibalism was well-documented, the practice had ceased before the cause of the disease was recognized. However, some scholars argue that although post-mortem dismemberment was the practice during funeral rites, cannibalism was not. Marvin Harris theorizes that it happened during a famine period coincident with the arrival of Europeans and was rationalized as a religious rite.

In 2003, a publication in Science received a large amount of press attention when it suggested that early humans may have practised extensive cannibalism. According to this research, genetic markers commonly found in modern humans worldwide suggest that today many people carry a gene that evolved as protection against the brain diseases that can be spread by consuming human brain tissue. A 2006 reanalysis of the data questioned this hypothesis, because it claimed to have found a data collection bias, which led to an erroneous conclusion. This claimed bias came from incidents of cannibalism used in the analysis not being due to local cultures, but having been carried out by explorers, stranded seafarers or escaped convicts. The original authors published a subsequent paper in 2008 defending their conclusions.

Myths, legends and folklore

Cannibalism features in the folklore and legends of many cultures and is most often attributed to evil characters or as extreme retribution for some wrongdoing. Examples include the witch in "Hansel and Gretel", Lamia of Greek mythology and the witch Baba Yaga of Slavic folklore.

A number of stories in Greek mythology involve cannibalism, in particular the eating of close family members, e.g., the stories of Thyestes, Tereus and especially Cronus, who became Saturn in the Roman pantheon. The story of Tantalus is another example, though here a family member is prepared for consumption by others.

The wendigo is a creature appearing in the legends of the Algonquian people. It is thought of variously as a malevolent cannibalistic spirit that could possess humans or a monster that humans could physically transform into. Those who indulged in cannibalism were at particular risk, and the legend appears to have reinforced this practice as taboo. The Zuni people tell the story of the Átahsaia – a giant who cannibalizes his fellow demons and seeks out human flesh.

The wechuge is a demonic cannibalistic creature that seeks out human flesh appearing in the mythology of the Athabaskan people. It is said to be half monster and half human-like; however, it has many shapes and forms.

Skepticism

William Arens, author of The Man-Eating Myth: Anthropology and Anthropophagy, questions the credibility of reports of cannibalism and argues that the description by one group of people of another people as cannibals is a consistent and demonstrable ideological and rhetorical device to establish perceived cultural superiority. Arens bases his thesis on a detailed analysis of various "classic" cases of cannibalism reported by explorers, missionaries, and anthropologists. He claims that all of them were steeped in racism, unsubstantiated, or based on second-hand or hearsay evidence. Though widely discussed, Arens's book generally failed to convince the academic community. Claude Lévi-Strauss observes that, in spite of his "brilliant but superficial book ... [n]o serious ethnologist disputes the reality of cannibalism". Shirley Lindenbaum notes that, while after "Arens['s] ... provocative suggestion ... many anthropologists ... reevaluated their data", the outcome was an improved and "more nuanced" understanding of where, why and under which circumstances cannibalism took place rather than a confirmation of his claims: "Anthropologists working in the Americas, Africa, and Melanesia now acknowledge that institutionalized cannibalism occurred in some places at some times. Archaeologists and evolutionary biologists are taking cannibalism seriously."

Lindenbaum and others point out that Arens displays a "strong ethnocentrism". His refusal to admit that institutionalized cannibalism ever existed seems to be motivated by the implied idea "that cannibalism is the worst thing of all" – worse than any other behaviour people engaged in, and therefore uniquely suited to vilify others. Kajsa Ekholm Friedman calls this "a remarkable opinion in a culture [the European/American one] that has been capable of the most extreme cruelty and destructive behavior, both at home and in other parts of the world."

She observes that, contrary to European values and expectations, "[i]n many parts of the Congo region there was no negative evaluation of cannibalism. On the contrary, people expressed their strong appreciation of this very special meat and could not understand the hysterical reactions from the white man's side." And why indeed, she goes on to ask, should they have had the same negative reactions to cannibalism as Arens and his contemporaries? Implicitly he assumes that everybody throughout human history must have shared the strong taboo placed by his own culture on cannibalism, but he never attempts to explain why this should be so, and "neither logic nor historical evidence justifies" this viewpoint, as Christian Siefkes commented.

Accusations of cannibalism could be used to characterize indigenous peoples as "uncivilized", "primitive", or even "inhuman." While this means that the reliability of reports of cannibal practices must be carefully evaluated especially if their wording suggests such a context, many actual accounts do not fit this pattern. The earliest firsthand account of cannibal customs in the Caribbean comes from Diego Álvarez Chanca, who accompanied Christopher Columbus on his second voyage. His description of the customs of the Caribs of Guadeloupe includes their cannibalism (men killed or captured in war were eaten, while captured boys were "castrated [and used as] servants until they gr[e]w up, when they [were] slaughtered" for consumption), but he nevertheless notes "that these people are more civilized than the other islanders" (who did not practice cannibalism). Nor was he an exception. Among the earliest reports of cannibalism in the Caribbean and the Americas, there are some (like those of Amerigo Vespucci) that seem to mostly consist of hearsay and "gross exaggerations", but others (by Chanca, Columbus himself, and other early travellers) show "genuine interest and respect for the natives" and include "numerous cases of sincere praise".

Reports of cannibalism from other continents follow similar patterns. Condescending remarks can be found, but many Europeans who described cannibal customs in Central Africa wrote about those who practised them in quite positive terms, calling them "splendid" and "the finest people" and not rarely, like Chanca, actually considering them as "far in advance of" and "intellectually and morally superior" to the non-cannibals around them. Writing from Melanesia, the missionary George Brown explicitly rejects the European prejudice of picturing cannibals as "particularly ferocious and repulsive", noting instead that many cannibals he met were "no more ferocious than" others and "indeed ... very nice people".

Reports or assertions of cannibal practices could nevertheless be used to promote the use of military force as a means of "civilizing" and "pacifying" the "savages". During the Spanish conquest of the Aztec Empire and its earlier conquests in the Caribbean there were widespread reports of cannibalism, and cannibals became exempted from Queen Isabella's prohibition on enslaving the indigenous. Another example of the sensationalism of cannibalism and its connection to imperialism occurred during Japan's 1874 expedition to Taiwan. As Robert Eskildsen describes, Japan's popular media "exaggerated the aborigines' violent nature", in some cases by wrongly accusing them of cannibalism.

This Horrid Practice: The Myth and Reality of Traditional Maori Cannibalism (2008) by New Zealand historian Paul Moon received a hostile reception by some Māori, who felt the book tarnished their whole people. However, the factual accuracy of the book was not seriously disputed and even critics such as Margaret Mutu grant that cannibalism was "definitely" practised and that it was "part of our [Māori] culture."

History

Among modern humans, cannibalism has been practised by various groups. It was practised by humans in Prehistoric Europe, Mesoamerica, South America, among Iroquoian peoples in North America, Maori in New Zealand, the Solomon Islands, parts of West Africa and Central Africa, some of the islands of Polynesia, New Guinea, Sumatra, and Fiji. Evidence of cannibalism has been found in ruins associated with the Ancestral Puebloans of the Southwestern United States as well (at Cowboy Wash in Colorado).

Prehistory

There is evidence, both archaeological and genetic, that cannibalism has been practised for hundreds of thousands of years by early Homo sapiens and archaic hominins. Human bones that have been "de-fleshed" by other humans go back 600,000 years. The oldest Homo sapiens bones (from Ethiopia) show signs of this as well. Some anthropologists, such as Tim D. White, suggest that cannibalism was common in human societies prior to the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic period. This theory is based on the large amount of "butchered human" bones found in Neanderthal and other Lower/Middle Paleolithic sites.

It seems likely that not all instances of prehistoric cannibalism were due to the same reason, just as cannibalistic acts known from the historical record have been motivated by a variety of reasons. One suggested reason for cannibalism in the Lower and Middle Paleolithic have been food shortages. It has been also suggested that removing dead bodies through ritual (funerary) cannibalism was a means of predator control, aiming to eliminate predators' and scavengers' access to hominid (and early human) bodies. Jim Corbett proposed that after major epidemics, when human corpses are easily accessible to predators, there are more cases of man-eating leopards, so removing dead bodies through ritual cannibalism (before the cultural traditions of burying and burning bodies appeared in human history) might have had practical reasons for hominids and early humans to control predation.

The oldest archaeological evidence of hominid cannibalism comes from the Gran Dolina cave in northern Spain. The remains of several individuals who died about 800,000 years ago and may have belongs to the Homo antecessor species show unmistakable signs of having been butchered and consumed in the same way as animals whose bones were also found at the site. They belong to at least eleven individuals, all of which were young (ranging from infancy to late teenhood). A study of this case considers it an instance of "nutritional" cannibalism, where individuals belonging to hostile or unrelated groups were hunted, killed, and eaten much like animals. Based on the placement and processing of human and animal remains, the authors conclude that cannibalism was likely a "repetitive behavior over time as part of a culinary tradition", not caused by starvation or other exceptional circumstances. They suggest that young individuals (more than half of which were children under ten) were targeted because they "posed a lower risk for hunters" and because this was an effective means for limiting the growth of competing groups.

Several sites in Croatia, France, and Spain yield evidence that the Neanderthals sometimes practised cannibalism, though the interpretation of some of the finds remains controversial.

Neanderthals could also fall victim to cannibalism by anatomically modern humans. Evidence found in southwestern France indicates that the latter butchered and ate a Neanderthal child about 30,000 years ago; it is unknown whether the child was killed by them or died of other reasons. The find has been considered as strengthening the conjecture that modern humans might have hunted Neanderthals and in this way contributed to their extinction.

In Gough's Cave, England, remains of human bones and skulls, around 14,700 years old, suggest that cannibalism took place amongst the people living in or visiting the cave, and that they may have used human skulls as drinking vessels.

The archaeological site of Herxheim in southwestern Germany was a ritual center and a mass grave formed by people of the Linear Pottery culture in Neolithic Europe. It contained the scattered remains of more than 1000 individuals from different, in some cases faraway regions, who died around 5000 BCE. Whether they were war captives or human sacrifices is unclear, but the evidence indicates that their corpses were spit-roasted whole and then consumed.

At Fontbrégoua Cave in southeastern France, the remains of six people who lived about 7,000 years ago were found (two children, one adolescent, and three adults), in addition to animal bones. The patterns of cut marks indicate that both humans and animals were skinned and processed in similar ways. Since the human victims were all processed at the same time, the main excavator, Paola Villa, suspects that they all belonged to the same family or extended family and were killed and butchered together, probably during some kind of violent conflict. Others have argued that the traces were caused by defleshing rituals preceding a secondary burial, but the fact that both humans and wild and domestic animals were processed in the same way makes this unlikely; moreover, Villa argues that the observed traces better fit a typical butchering process than a secondary burial.

Researchers have also found physical evidence of cannibalism from more recent times, including from Prehistoric Britain. In 2001, archaeologists at the University of Bristol found evidence of cannibalism practised around 2000 years ago in Gloucestershire, South West England. This is in agreement with Ancient Roman reports that the Celts in Britain practised human sacrifice, killing and eating captured enemies as well as convicted criminals.

Early history

Cannibalism is mentioned many times in early history and literature. The oldest written reference may be from the tomb of the ancient Egyptian king Unas (24th century BCE). It contained a hymn in praise of the king portraying him as a cannibal who eats both "men" and "gods", thus indicating an attitude towards cannibalism quite different from the modern one.

Herodotus claimed in his Histories (5th century BCE) that after eleven days' voyage up the Borysthenes (Dnieper River) one reached a desolated land that extended for a long way, followed by a country of man-eaters (other than the Scythians), and beyond it by another desolated and uninhabited area.

The Stoic philosopher Chrysippus approved of eating one's dead relatives in a funerary ritual, noting that such rituals were common among many peoples.

Cassius Dio recorded cannibalism practised by the bucoli, Egyptian tribes led by Isidorus against Rome. They sacrificed and consumed two Roman officers in a ritualistic fashion, swearing an oath over their entrails.

According to Appian, during the Roman siege of Numantia in the 2nd century BCE, the population of Numantia (in today's Spain) was reduced to cannibalism and suicide. Cannibalism was also reported by Josephus during the siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE.

Jerome, in his letter Against Jovinianus (written 393 CE), discusses how people come to their present condition as a result of their heritage, and lists several examples of peoples and their customs. In the list, he mentions that he has heard that the Attacotti (in Britain) eat human flesh and that the Massagetae and Derbices (two Central Asian peoples) kill and eat old people, considering this a more desirable fate than dying of old age and illness.

Middle Ages

The Americas

There is universal agreement that some Mesoamerican people practised human sacrifice, but there is a lack of scholarly consensus as to whether cannibalism in pre-Columbian America was widespread. At one extreme, anthropologist Marvin Harris, author of Cannibals and Kings, has suggested that the flesh of the victims was a part of an aristocratic diet as a reward, since the Aztec diet was lacking in proteins. While most historians of the pre-Columbian era believe that there was ritual cannibalism related to human sacrifices, they do not support Harris's thesis that human flesh was ever a significant portion of the Aztec diet. Others have hypothesized that cannibalism was part of a blood revenge in war.

West Africa

When the Moroccan explorer Ibn Battuta visited the Mali Empire in the 1350s, he was surprised to see sultan Sulayman give "a slave girl as part of his reception-gift" to a group of warriors from a cannibal region who had come to visit his court. "They slaughtered her and ate her and smeared their faces and hands with her blood and came in gratitude to the sultan." He was told that the sultan did so every time he received the cannibal guests. Though a Muslim like Ibn Battuta himself, he apparently considered catering to his visitors' preferences more important than whatever reservations he may have had about the practice. Other Muslim authors writing around that time also report that cannibalism was practised in some West Africa regions and that slave girls were sometimes slaughtered for food, since "[t]heir flesh is the best thing we have to eat."

Europe and Europeans

Reports of cannibalism were recorded during the First Crusade, as crusaders were alleged to have fed on the bodies of their dead opponents following the siege of Ma'arra. Amin Maalouf also alleges further cannibalism incidents on the march to Jerusalem, and to the efforts made to delete mention of these from Western history. Even though this account does not appear in any contemporary Muslim chronicle. The famine and cannibalism are recognised as described by Fulcher of Chartres, but the torture and the killing of Muslim captives for cannibalism by Radulph of Caen are very unlikely since no Arab or Muslim records of the events exist. Had they occurred, they would have probably been recorded. That has been noted by BBC Timewatch series, the episode The Crusades: A Timewatch Guide, which included experts Thomas Asbridge and Muslim Arabic historian Fozia Bora, who state that Radulph of Caen's description does not appear in any contemporary Muslim chronicle. During Europe's Great Famine of 1315–17, there were many reports of cannibalism among the starving populations. In North Africa, as in Europe, there are references to cannibalism as a last resort in times of famine.

For a brief time in Europe, an unusual form of cannibalism occurred when thousands of Egyptian mummies preserved in bitumen were ground up and sold as medicine. The practice developed into a wide-scale business which flourished until the late 16th century. This "fad" ended because the mummies were revealed actually to be recently killed slaves. Two centuries ago, mummies were still believed to have medicinal properties against bleeding, and were sold as pharmaceuticals in powdered form (see human mummy confection and mummia).

Western Asia

Charges of cannibalism were levied against the Qizilbash of the Safavid Ismail.

China

Cannibalism has been repeatedly recorded throughout China's well-documented history. The sinologist Bengt Pettersson found references to more than three hundred different episodes of cannibalism in the Official Dynastic Histories alone. Most episodes occurred in the context of famine or war, or were otherwise motivated by vengeance or medical reasons. More than half of the episodes recorded in the Official Histories describe cases motivated by food scarcity during famines or in times of war. Pettersson observes that the records of such events "neither encouraged nor condemned" the consumption of human flesh under such circumstances, rather accepting it as an unavoidable way of "coping with a life-threatening situation".

In other cases, cannibalism was an element of vengeance or punishment – eating the hearts and livers, or sometimes the whole bodies, of killed enemies was a way of further humiliating them and sweetening the revenge. Both private individuals and state officials engaged in such acts, especially from the 4th to the 10th century CE, but in some cases right until the end of Imperial China (in 1912). More than 70 cases are listed in the Official Histories alone. In warfare, human flesh could be eaten because of a lack of other provisions, but also out of hatred against the enemy or to celebrate one's victory. Not just enemy fighters, but also their "servants and concubines were all steamed and eaten", according to one account.

At least since the Tang dynasty (618–907), the consumption of human flesh was considered a highly effective medical treatment, recommended by the Bencao Shiyi, an influential medical reference book published in the early 8th century, as well as in similar later manuals. Together with the ethical ideal of filial piety, according to which young people were supposed to do everything in their power to support their parents and parents-in-law, this idea lead to a unique form of voluntary cannibalism, in which a young person cut some of the flesh out of their body and gave it to an ill parent or parent-in-law for consumption. The majority of the donors were women, frequently daughters-in-law of the patient.

The devoted daughter-in-law would tie her thigh or her arm very tightly with a piece of clothing. She would then use a very sharp knife to quickly slice off a piece from her upper arm or upper thigh. The flesh would immediately be mixed in with soup or gruel, which had been heated in preparation, and this would then be offered to the dying mother-in-law or father-in-law.

The Official Histories describe more than 110 cases of such voluntary offerings that took place between the early 7th and the early 20th century. While these acts were (at least nominally) voluntary and the donors usually (though not always) survived them, several sources also report of children and adolescents who were killed so that their flesh could be eaten for medical purposes.

During the Tang dynasty, cannibalism was supposedly resorted to by rebel forces early in the period (who were said to raid neighbouring areas for victims to eat), and (on a large scale) by both soldiers and civilians during the siege of Suiyang, a decisive episode of the An Lushan Rebellion. Eating an enemy's heart and liver was also repeatedly mentioned as a feature of both official punishments and private vengeance. The final decades of the dynasty were marked by large-scale rebellions, during which both rebels and regular soldiers butchered prisoners for food and killed and ate civilians. Sometimes "the rebels captured by government troops were [even] sold as food", according to several of the Official Histories, while warlords likewise relied on the sale of human flesh to finance their rebellions. An Arab traveller visiting China during this time noted with surprise: "cannibalism [is] permissible for them according to their legal code, for they trade in human flesh in their markets."

References to cannibalizing the enemy also appear in poetry written in the subsequent Song dynasty (960–1279) – for example, in Man Jiang Hong – although they are perhaps meant symbolically, expressing hatred towards the enemy. The Official Histories covering this period record various cases of rebels and bandits eating the flesh of their victims.

The flesh of executed criminals was sometimes cut off and sold for consumption. During the Tang dynasty a law was enacted that forbade this practice, but whether the law was effectively enforced is unclear. The sale of human flesh is also repeatedly mentioned during famines, in accounts ranging from the 6th to the 15th century. Several of these accounts mention that animal flesh was still available, but had become so expensive that few could afford it. Dog meat was five times as expensive as human flesh, according to one such report. Sometimes, poor men sold their own wives or children to butchers who slaughtered them and sold their flesh. Cannibalism in famine situations seems to have been generally tolerated by the authorities, who did not intervene when such acts occurred.

A number of accounts suggests that human flesh was occasionally eaten for culinary reasons. An anecdote told about Duke Huan of Qi (7th century BCE) claims that he was curious about the taste of "steamed child", having already eaten everything else. His cook supposedly killed his own son to prepare the dish, and Duke Huan judged it to be "the best food of all". In later times, wealthy men, among them a son of the 4th-century emperor Shi Hu and an "open and high-spirited" man who lived in the 7th century CE, served the flesh of purchased women or children during lavish feasts.The sinologist Robert des Rotours observes that while such acts were not common, they don't seem to have been rare exceptions, and the hosts apparently did not have to face ostracism or legal prosection. The historian Key Ray Chong even concludes that "learned cannibalism was often practiced ... for culinary appreciation, and exotic dishes [of human flesh] were prepared for jaded upper-class palates".

The Official Histories mention 10th-century officials who liked to eat the flesh of babies and children, and during the Jin dynasty (1115–1234), human flesh seems to have been readily available at the home of a general, who supposedly served it to one of his guests as a practical joke. Accounts from the 12th to 14th centuries indicate that both soldiers and writers praised human flesh as particularly tasty, especially if it came from children.

Pettersson observes that people generally seem to have had less reservations about the consumption of human flesh than one might expect today. While survival cannibalism during famines was regarded a lamentable necessity, accounts explaining the practice as due to other reasons, such as vengeance or filial piety, were generally even positive.

Early modern and colonial era

The Americas

European explorers and colonizers brought home many stories of cannibalism practised by the native peoples they encountered. In Spain's overseas expansion to the New World, the practice of cannibalism was reported by Christopher Columbus in the Caribbean islands, and the Caribs were greatly feared because of their supposed practice of it. Queen Isabel of Castile had forbidden the Spaniards to enslave the indigenous, unless they were "guilty" of cannibalism. The accusation of cannibalism became a pretext for attacks on indigenous groups and justification for the Spanish conquest. In Yucatán, shipwrecked Spaniard Jerónimo de Aguilar, who later became a translator for Hernán Cortés, reported to have witnessed fellow Spaniards sacrificed and eaten, but escaped from captivity where he was being fattened for sacrifice himself. In the Florentine Codex (1576) compiled by Franciscan Bernardino de Sahagún from information provided by indigenous eyewitnesses has questionable evidence of Mexica (Aztec) cannibalism. Franciscan friar Diego de Landa reported on Yucatán instances.

In early Brazil, there is reportage of cannibalism among the Tupinamba. It is recorded about the natives of the captaincy of Sergipe in Brazil: "They eat human flesh when they can get it, and if a woman miscarries devour the abortive immediately. If she goes her time out, she herself cuts the navel-string with a shell, which she boils along with the secondine [i.e. placenta], and eats them both." (see human placentophagy).

The 1913 Handbook of Indians of Canada (reprinting 1907 material from the Bureau of American Ethnology), claims that North American natives practising cannibalism included "... the Montagnais, and some of the tribes of Maine; the Algonkin, Armouchiquois, Iroquois, and Micmac; farther west the Assiniboine, Cree, Foxes, Chippewa, Miami, Ottawa, Kickapoo, Illinois, Sioux, and Winnebago; in the south the people who built the mounds in Florida, and the Tonkawa, Attacapa, Karankawa, Caddo, and Comanche; in the northwest and west, portions of the continent, the Thlingchadinneh and other Athapascan tribes, the Tlingit, Heiltsuk, Kwakiutl, Tsimshian, Nootka, Siksika, some of the Californian tribes, and the Ute. There is also a tradition of the practice among the Hopi, and mentions of the custom among other tribes of New Mexico and Arizona. The Mohawk, and the Attacapa, Tonkawa, and other Texas tribes were known to their neighbours as 'man-eaters.'" The forms of cannibalism described included both resorting to human flesh during famines and ritual cannibalism, the latter usually consisting of eating a small portion of an enemy warrior. From another source, according to Hans Egede, when the Inuit killed a woman accused of witchcraft, they ate a portion of her heart.

As with most lurid tales of native cannibalism, these stories are treated with a great deal of scrutiny, as accusations of cannibalism were often used as justifications for the subjugation or destruction of "savages". The historian Patrick Brantlinger suggests that Indigenous peoples that were colonized were being dehumanized as part of the justification for the atrocities.

Polynesia and Melanesia

The very first encounter between Europeans and Māori may have involved cannibalism of a Dutch sailor. In June 1772, the French explorer Marion du Fresne and 26 members of his crew were killed and eaten in the Bay of Islands. In an 1809 incident known as the Boyd massacre, about 66 passengers and crew of the Boyd were killed and eaten by Māori on the Whangaroa peninsula, Northland. Cannibalism was already a regular practice in Māori wars. In another instance, on July 11, 1821, warriors from the Ngapuhi tribe killed 2,000 enemies and remained on the battlefield "eating the vanquished until they were driven off by the smell of decaying bodies". Māori warriors fighting the New Zealand government in Titokowaru's War in New Zealand's North Island in 1868–69 revived ancient rites of cannibalism as part of the radical Hauhau movement of the Pai Marire religion.

In parts of Melanesia, cannibalism was still practised in the early 20th century, for a variety of reasons – including retaliation, to insult an enemy people, or to absorb the dead person's qualities. One tribal chief, Ratu Udre Udre in Rakiraki, Fiji, is said to have consumed 872 people and to have made a pile of stones to record his achievement. Fiji was nicknamed the "Cannibal Isles" by European sailors, who avoided disembarking there. The dense population of the Marquesas Islands, in what is now French Polynesia, was concentrated in narrow valleys, and consisted of warring tribes, who sometimes practised cannibalism on their enemies. Human flesh was called "long pig". W. D. Rubinstein wrote:

It was considered a great triumph among the Marquesans to eat the body of a dead man. They treated their captives with great cruelty. They broke their legs to prevent them from attempting to escape before being eaten, but kept them alive so that they could brood over their impending fate. ... With this tribe, as with many others, the bodies of women were in great demand.

Among settlers, sailors, and explorers

This period of time was also rife with instances of explorers and seafarers resorting to cannibalism for survival. There is archaeological and written evidence for English settlers' cannibalism in 1609 in the Jamestown Colony under famine conditions, during a period which became known as Starving Time.

Sailors shipwrecked or lost at sea repeatedly resorted to cannibalism to face off starvation. The survivors of the sinking of the French ship Méduse in 1816 resorted to cannibalism after four days adrift on a raft. Their plight was made famous by Théodore Géricault's painting Raft of the Medusa. After a whale sank the Essex of Nantucket on 20 November 1820 the survivors, in three small boats, resorted, by common consent, to cannibalism in order for some to survive. This event became an important source of inspiration for Herman Melville's Moby-Dick.

The case of R v Dudley and Stephens (1884) is an English criminal case which dealt with four crew members of an English yacht, the Mignonette, who were cast away in a storm some 2,600 kilometres (1,600 mi) from the Cape of Good Hope. After several days, one of the crew, a seventeen-year-old cabin boy, fell unconscious due to a combination of the famine and drinking seawater. The others (one possibly objecting) decided to kill him and eat him. They were picked up four days later. Two of the three survivors were found guilty of murder. A significant outcome of this case was that necessity in English criminal law was determined to be no defence against a charge of murder. This was a break with the traditional understanding among sailors, which had been that selecting a victim for killing and consumption was acceptable in a starvation situation as long as lots were drawn so that all faced an equal risk of being killed.

On land, travellers through sparsely inhabited regions and explorers of unknown areas sometimes ate human flesh after running out of other provisions. In a famous example from the 1840s, the members of Donner Party found themselves stranded by snow in the Donner Pass, a high mountain pass in California, without adequate supplies during the Mexican–American War, leading to several instances of cannibalism, including the murder of two young Native American men for food. Sir John Franklin's lost polar expedition, which took place at approximately the same time, is another example of cannibalism out of desperation.

In frontier situations where there was no strong authority, some individuals got used to killing and eating others even in situations where other food would have been available. One notorious case was the mountain man Boone Helm, who become known as "The Kentucky Cannibal" for eating several of his fellow travellers, from 1850 until his eventual hanging in 1864.

Central and West Africa

Roger Casement, writing to a consular colleague in Lisbon on August 3, 1903, from Lake Mantumba in the Congo Free State, said:

"The people round here are all cannibals. You never saw such a weird looking lot in your life. There are also dwarfs (called Batwas) in the forest who are even worse cannibals than the taller human environment. They eat man flesh raw! It's a fact." Casement then added how assailants would "bring down a dwarf on the way home, for the marital cooking pot ... The Dwarfs, as I say, dispense with cooking pots and eat and drink their human prey fresh cut on the battlefield while the blood is still warm and running. These are not fairy tales, my dear Cowper, but actual gruesome reality in the heart of this poor, benighted savage land."

During the 1892–1894 war between the Congo Free State and the Swahili–Arab city-states of Nyangwe and Kasongo in Eastern Congo, there were reports of widespread cannibalization of the bodies of defeated Arab combatants by the Batetela allies of Belgian commander Francis Dhanis. The Batetela, "like most of their neighbors were inveterate cannibals." According to Dhanis's medical officer, Captain Hinde, their town of Ngandu had "at least 2,000 polished human skulls" as a "solid white pavement in front" of its gates, with human skulls crowning every post of the stockade.

In April 1892, 10,000 of the Batetela, under the command of Gongo Lutete, joined forces with Dhanis in a campaign against the Swahili–Arab leaders Sefu and Mohara. After one early skirmish in the campaign, Hinde "noticed that the bodies of both the killed and wounded had vanished." When fighting broke out again, Hinde saw his Batetela allies drop human arms, legs and heads on the road. One young Belgian officer wrote home: "Happily Gongo's men ate them up [in a few hours]. It's horrible but exceedingly useful and hygienic ... I should have been horrified at the idea in Europe! But it seems quite natural to me here. Don't show this letter to anyone indiscreet." After the massacre at Nyangwe, Lutete "hid himself in his quarters, appalled by the sight of thousands of men smoking human hands and human chops on their camp fires, enough to feed his army for many days."

In West Africa, the Leopard Society was a cannibalistic secret society that existed until the mid-1900s. Centered in Sierra Leone, Liberia and Ivory Coast, the Leopard men would dress in leopard skins, and waylay travellers with sharp claw-like weapons in the form of leopards' claws and teeth. The victims' flesh would be cut from their bodies and distributed to members of the society.

Early 20th century to present

After World War I, cannibalism continued to occur as a ritual practice and in times of drought or famine. Occasional cannibal acts committed by individual criminals are documented as well throughout the 20th and 21st centuries.

World War II

Many instances of cannibalism by necessity were recorded during World War II. For example, during the 872-day siege of Leningrad, reports of cannibalism began to appear in the winter of 1941–1942, after all birds, rats, and pets were eaten by survivors. Leningrad police even formed a special division to combat cannibalism.

Some 2.8 million Soviet POWs died in Nazi custody in less than eight months during 1941–42. According to the USHMM, by the winter of 1941, "starvation and disease resulted in mass death of unimaginable proportions". This deliberate starvation led to many incidents of cannibalism.

Following the Soviet victory at Stalingrad it was found that some German soldiers in the besieged city, cut off from supplies, resorted to cannibalism. Later, following the German surrender in January 1943, roughly 100,000 German soldiers were taken prisoner of war (POW). Almost all of them were sent to POW camps in Siberia or Central Asia where, due to being chronically underfed by their Soviet captors, many resorted to cannibalism. Fewer than 5,000 of the prisoners taken at Stalingrad survived captivity.

Cannibalism took place in the concentration and death camps in the Independent State of Croatia (NDH), a Nazi German puppet state which was governed by the fascist Ustasha organization, who committed the Genocide of Serbs and the Holocaust in NDH. Some survivors testified that some of the Ustashas drank the blood from the slashed throats of the victims.

The Australian War Crimes Section of the Tokyo tribunal, led by prosecutor William Webb (the future Judge-in-Chief), collected numerous written reports and testimonies that documented Japanese soldiers' acts of cannibalism among their own troops, on enemy dead, as well as on Allied prisoners of war in many parts of the Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere. In September 1942, Japanese daily rations on New Guinea consisted of 800 grams of rice and tinned meat. However, by December, this had fallen to 50 grams. According to historian Yuki Tanaka, "cannibalism was often a systematic activity conducted by whole squads and under the command of officers".

In some cases, flesh was cut from living people. A prisoner of war from the British Indian Army, Lance Naik Hatam Ali, testified that in New Guinea: "the Japanese started selecting prisoners and every day one prisoner was taken out and killed and eaten by the soldiers. I personally saw this happen and about 100 prisoners were eaten at this place by the Japanese. The remainder of us were taken to another spot 80 kilometres (50 miles) away where 10 prisoners died of sickness. At this place, the Japanese again started selecting prisoners to eat. Those selected were taken to a hut where their flesh was cut from their bodies while they were alive and they were thrown into a ditch where they later died."

Another well-documented case occurred in Chichi-jima in February 1945, when Japanese soldiers killed and consumed five American airmen. This case was investigated in 1947 in a war crimes trial, and of 30 Japanese soldiers prosecuted, five (Maj. Matoba, Gen. Tachibana, Adm. Mori, Capt. Yoshii, and Dr. Teraki) were found guilty and hanged. In his book Flyboys: A True Story of Courage, James Bradley details several instances of cannibalism of World War II Allied prisoners by their Japanese captors. The author claims that this included not only ritual cannibalization of the livers of freshly killed prisoners, but also the cannibalization-for-sustenance of living prisoners over the course of several days, amputating limbs only as needed to keep the meat fresh.

There are more than 100 documented cases in Australia's government archives of Japanese soldiers practising cannibalism on enemy soldiers and civilians in New Guinea during the war. For instance, from an archived case, an Australian lieutenant describes how he discovered a scene with cannibalized bodies, including one "consisting only of a head which had been scalped and a spinal column" and that "[i]n all cases, the condition of the remains were such that there can be no doubt that the bodies had been dismembered and portions of the flesh cooked". In another archived case, a Pakistani corporal (who was captured in Singapore and transported to New Guinea by the Japanese) testified that Japanese soldiers cannibalized a prisoner (some were still alive) per day for about 100 days. There was also an archived memo, in which a Japanese general stated that eating anyone except enemy soldiers was punishable by death. Toshiyuki Tanaka, a Japanese scholar in Australia, mentions that it was done "to consolidate the group feeling of the troops" rather than due to food shortage in many of the cases. Tanaka also states that the Japanese committed the cannibalism under supervision of their senior officers and to serve as a power projection tool.

Jemadar Abdul Latif (VCO of the 4/9 Jat Regiment of the British Indian Army and POW rescued by the Australians at Sepik Bay in 1945) stated that the Japanese soldiers ate both Indian POWs and local New Guinean people. At the camp for Indian POWs in Wewak, where many died and 19 POWs were eaten, the Japanese doctor and lieutenant Tumisa would send an Indian out of the camp after which a Japanese party would kill and eat flesh from the body as well as cut off and cook certain body parts (liver, buttock muscles, thighs, legs, and arms), according to Captain R. U. Pirzai in a The Courier-Mail report of 25 August 1945.

South America

When Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571 crashed on a glacier in the Andes on October 13, 1972, many survivors resorted to eating the deceased during their 72 days in the mountains. The experiences and memories of the survivors became the source of several books and films. In an account of the accident and aftermath, survivor Roberto Canessa described the decision to eat the pilots and their dead friends and family members:

Our common goal was to survive – but what we lacked was food.... After just a few days, we were feeling the sensation of our own bodies consuming themselves just to remain alive. Before long, we would become too weak to recover from starvation.

We knew the answer, but it was too terrible to contemplate.

The bodies of our friends and team-mates, preserved outside in the snow and ice, contained vital, life-giving protein that could help us survive. But could we do it?

For a long time, we agonized.... Truly, we were pushing the limits of our fear.

North America

In 1991, Jeffrey Dahmer of Milwaukee, Wisconsin, was arrested after one of his intended victims managed to escape. Found in Dahmer's apartment were two human hearts, an entire torso, a bag full of human organs from his victims, and a portion of arm muscle. He stated that he planned to consume all of the body parts over the next few weeks.

West Africa

In the 1980s, Médecins Sans Frontières, the international medical charity, supplied photographic and other documentary evidence of ritualized cannibal feasts among the participants in Liberia's internecine strife preceding the First Liberian Civil War to representatives of Amnesty International. Amnesty International declined to publicize this material; the Secretary-General of the organization, Pierre Sane, said at the time in an internal communication that "what they do with the bodies after human rights violations are committed is not part of our mandate or concern". The existence of cannibalism on a wide scale in Liberia was subsequently verified.

A few years later, reported of cannibal acts committed during the Second Liberian Civil War and Sierra Leone Civil War emerged.

Central Africa

Reports from the Belgian Congo indicate that cannibalism was still widely practised in some regions in the 1920s. Hermann Norden, an American who visited the Kasai region in 1923, found that "cannibalism was commonplace". People were afraid of walking outside of populated places because there was a risk of being attacked, killed, and eaten. Norden talked with a Belgian who "admitted that it was quite likely he had occasionally been served human flesh without knowing what he was eating" – it was simply a dish that appeared on the tables from time.

Other travellers heard persistent rumours that there was still a certain underground trade in slaves, some of whom (adults and children alike) were regularly killed and then "cut up and cooked as ordinary meat", around both the Kasai and the Ubangi River. The colonial state seems to have done little to discourage or punish such acts. There are also reports that human flesh was sometimes sold at markets in both Kinshasa and Brazzaville, "right in the middle of European life."

Norden observed that cannibalism was so common that people talked about it quite "casual[ly]": "No stress was put upon it, nor horror shown. This person had died of fever; that one had been eaten. It was all a matter of the way one's luck held."

Even after World War II, human flesh still occasionally appeared on the tables. In 1950, a Belgian administrator ate a "remarkably delicious" dish, learning after he had finished "that the meat came from a young girl." A few years later, a Danish traveller was served a piece of the "soft and tender" flesh of a butchered woman.

During the Congo Crisis, which followed the country's independence in 1960, body parts of killed enemies were eaten and the flesh of war victims was sometimes sold for consumption. In Luluabourg (today Kananga), an American journalist saw a truck smeared with blood. A police commissioner investigating the scene told her that "[s]ixteen women and children" had been lured in a nearby village to enter the truck, kidnapped, and "butchered ... for meat." She also talked with a Presbyterian missionary, who excused this act as due to "protein need.... The bodies of their enemies are the only source of protein available."

In conflict situations, cannibalism persisted into the 21st century. During the first decade of the new century, cannibal acts have been reported from the Second Congo War and the Ituri conflict in the northeast of the Democratic Republic of the Congo. According to UN investigators, fighters belonging to several factions "grilled" human bodies "on a barbecue"; young girls were boiled "alive in ... big pots filled with boiling water and oil" or "cut into small pieces ... and then eaten."

A UN human rights expert reported in July 2007 that sexual atrocities committed by rebel groups as well as by armed forces and national police against Congolese women go "far beyond rape" and include sexual slavery, forced incest, and cannibalism. In the Ituri region, much of the violence, which included "widespread cannibalism", was consciously directed against pygmies, who were believed to be relatively helpless and even considered subhuman by some other Congolese.

UN investigators also collected eyewitness accounts of cannibalism during a violent conflict that shook the Kasai region in 2016/2017. Various parts of killed enemies and beheaded captives were cooked and eaten, including their heads, thighs, and penises.

Cannibalism has also been reported from the Central African Republic, north of the Congo Basin. Jean-Bédel Bokassa ruled the country from 1966 to 1979 as dictator and finally as self-declared emperor. Tenacious rumours that he liked to dine on the flesh of opponents and political prisoners were substantiated by several testimonies during his eventual trial in 1986/1987. Bokassa's successor David Dacko stated that he had seen photographs of butchered bodies hanging in the cold-storage rooms of Bokassa's palace immediately after taking power in 1979. These or similar photos, said to show a walk-in freezer containing the bodies of schoolchildren arrested in April 1979 during protests and beat to death in the 1979 Ngaragba Prison massacre, were also published in Paris Match magazine. During the trial, Bokassa's former chef testified that he had repeatedly cooked human flesh from the palace's freezers for his boss's table. While Bokassa was found guilty of murder in at least twenty cases, the charge of cannibalism was nevertheless not taken into account for the final verdict, since the consumption of human remains is considered a misdemeanor under CAR law and all previously committed misdemeanors had been forgiven by a general amnesty declared in 1981.

Further acts of cannibalism were reported to have targeted the Muslim minority during the Central African Republic Civil War which started in 2012.

East Africa

In the 1970s the Ugandan dictator Idi Amin was reputed to practice cannibalism. More recently, the Lord's Resistance Army has been accused of routinely engaging in ritual or magical cannibalism. It is also reported by some that witch doctors in the country sometimes use the body parts of children in their medicine.

During the South Sudanese Civil War, cannibalism and forced cannibalism have been reported from South Sudan.

Central and Western Europe

Before 1931, The New York Times reporter William Seabrook, apparently disappointed that he had been unable to taste human flesh in West Africa, obtained from a hospital intern at the Sorbonne a chunk of this meat from the body of a healthy man killed in an accident, then cooked and ate it. He reported,

It was like good, fully developed veal, not young, but not yet beef. It was very definitely like that, and it was not like any other meat I had ever tasted. It was so nearly like good, fully developed veal that I think no person with a palate of ordinary, normal sensitiveness could distinguish it from veal. It was mild, good meat with no other sharply defined or highly characteristic taste such as for instance, goat, high game, and pork have. The steak was slightly tougher than prime veal, a little stringy, but not too tough or stringy to be agreeably edible. The roast, from which I cut and ate a central slice, was tender, and in color, texture, smell as well as taste, strengthened my certainty that of all the meats we habitually know, veal is the one meat to which this meat is accurately comparable.

Karl Denke, possible Carl Großmann and Fritz Haarmann, as well as Joachim Kroll were German murderers and cannibals active between the early 20th century and the 1970s. Armin Meiwes is a former computer repair technician who achieved international notoriety for killing and eating a voluntary victim in 2001, whom he had found via the Internet. After Meiwes and the victim jointly attempted to eat the victim's severed penis, Meiwes killed his victim and proceeded to eat a large amount of his flesh. He was arrested in December 2002. In January 2004, Meiwes was convicted of manslaughter and sentenced to eight years and six months in prison. Despite the victim's undisputed consent, the prosecutors successfully appealed this decision, and in a retrial that ended in May 2006, Meiwes was convicted of murder and sentenced to life imprisonment.

On July 23, 1988, Rick Gibson ate the flesh of another person in public. Because England does not have a specific law against cannibalism, he legally ate a canapé of donated human tonsils in Walthamstow High Street, London. A year later, on April 15, 1989, he publicly ate a slice of human testicle in Lewisham High Street, London. When he tried to eat another slice of human testicle at the Pitt International Galleries in Vancouver on July 14, 1989, the Vancouver police confiscated the testicle hors d'œuvre. However, the charge of publicly exhibiting a disgusting object was dropped, and he finally ate the piece of human testicle on the steps of the Vancouver court house on September 22, 1989.

In 2008, a British model called Anthony Morley was imprisoned for the killing, dismemberment and partial cannibalisation of his lover, magazine executive Damian Oldfield. In 1996, Morley was a contestant on the television programme God's Gift; one of the audience members of that edition was Damian Oldfield. Oldfield was a contestant of another edition of the show in October 1996. On 2 May 2008, it was announced that Morley had been arrested for the murder of Oldfield, who worked for the gay lifestyle magazine Bent. After inviting Oldfield into his Leeds flat, police believed that Morley killed him, removed a section of his leg and began cooking it, before he stumbled into a nearby kebab house around 2:30 in the morning, drenched in blood and asking that someone call the police. He was found guilty on 17 October 2008 and sentenced to life imprisonment for the crime.

Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union

In his book, The Gulag Archipelago, Soviet writer Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn described cases of cannibalism in 20th-century Soviet Union. Of the famine in Povolzhie (1921–1922) he wrote: "That horrible famine was up to cannibalism, up to consuming children by their own parents – the famine, which Russia had never known even in the Time of Troubles [in 1601–1603]".

The historian Orlando Figes observes that "thousands of cases" of cannibalism were reported, while the number of cases that were never reported was doubtless even higher. In Pugachyov, "it was dangerous for children to go out after dark since there were known to be bands of cannibals and traders who killed them to eat or sell their tender flesh." An inhabitant of a nearby village stated: "There are several cafeterias in the village – and all of them serve up young children." This was no exception – Figes estimates "that a considerable proportion of the meat in Soviet factories in the Volga area ... was human flesh." Various gangs specialized in "capturing children, murdering them and selling the human flesh as horse meat or beef", with the buyers happy to have found a source of meat in a situation of extreme shortage and often willing not to "ask too many questions".

Cannibalism was also widespread during the Holodomor, a man-made famine in Soviet Ukraine between 1932 and 1933.

Survival was a moral as well as a physical struggle. A woman doctor wrote to a friend in June 1933 that she had not yet become a cannibal, but was "not sure that I shall not be one by the time my letter reaches you". The good people died first. Those who refused to steal or to prostitute themselves died. Those who gave food to others died. Those who refused to eat corpses died. Those who refused to kill their fellow man died. ... At least 2,505 people were sentenced for cannibalism in the years 1932 and 1933 in Ukraine, though the actual number of cases was certainly much higher.

Most cases of cannibalism were "necrophagy, the consumption of corpses of people who had died of starvation". But the murder of children for food was common as well. Many survivors told of neighbours who had killed and eaten their own children. One woman, asked why she had done this, "answered that her children would not survive anyway, but this way she would". She was arrested by the police. The police also documented cases of children being kidnapped, killed, and eaten, and "stories of children being hunted down as food" circulated in many areas. A man who lived through the famine in his youth later remembered that "the availability of human flesh at market[s] was an open and acknowledged secret. People were glad" if they could buy it since "[t]here was no other means to survive."

In March 1933 the secret police in Kyiv province collected "ten or more reports of cannibalism every day" but concluded that "in reality there are many more such incidents", most of which went unreported. Those found guilty of cannibalism were often "imprisoned, executed, or lynched". But while the authorities were well informed about the extent of cannibalism, they also tried to suppress this information from becoming widely known, the chief of the secret police warning "that written notes on the subject do not circulate among the officials where they might cause rumours".

The Holodomor was part of the Soviet famine of 1930–1933, which devastated also other parts of the Soviet Union in the early 1930s. Multiple cases of cannibalism were also reported from Kazakhstan.

A few years later, starving people again resorted to cannibalism during the siege of Leningrad (1941–1944). About this time, Solzhenitsyn writes: "Those who consumed human flesh, or dealt with the human liver trading from dissecting rooms ... were accounted as the political criminals".

Of the building of Northern Railway Labor Camp ("Sevzheldorlag") Solzhenitsyn reports, "An ordinary hard working political prisoner almost could not survive at that penal camp. In the camp Sevzheldorlag (chief: colonel Klyuchkin) in 1946–47 there were many cases of cannibalism: they cut human bodies, cooked and ate."

The Soviet journalist Yevgenia Ginzburg was a long-term political prisoner who spent time in the Soviet prisons, Gulag camps and settlements from 1938 to 1955. She described in her memoir, Harsh Route (or Steep Route), of a case which she was directly involved in during the late 1940s, after she had been moved to the prisoners' hospital.

The chief warder shows me the black smoked pot, filled with some food: "I need your medical expertise regarding this meat." I look into the pot, and hardly hold vomiting. The fibres of that meat are very small, and don't resemble me anything I have seen before. The skin on some pieces bristles with black hair ... A former smith from Poltava, Kulesh worked together with Centurashvili. At this time, Centurashvili was only one month away from being discharged from the camp ... And suddenly he surprisingly disappeared ... The wardens searched for two more days, and then assumed that it was an escape case, though they wondered why, since his imprisonment period was almost over ... The crime was there. Approaching the fireplace, Kulesh killed Centurashvili with an axe, burned his clothes, then dismembered him and hid the pieces in snow, in different places, putting specific marks on each burial place. ... Just yesterday, one body part was found under two crossed logs.

India

The Aghori are Indian ascetics who believe that eating human flesh confers spiritual and physical benefits, such as prevention of ageing. They claim to only eat those who have voluntarily granted their body to the sect upon their death, but an Indian TV crew witnessed one Aghori feasting on a corpse discovered floating in the Ganges and a member of the Dom caste reports that Aghori often take bodies from cremation ghats (or funeral pyres).

China

Cannibalism is documented to have occurred in rural China during the severe famine that resulted from the Great Leap Forward (1958–1962).

During Mao Zedong's Cultural Revolution (1966–1976), local governments' documents revealed hundreds of incidents of cannibalism for ideological reasons, including large-scale cannibalism during the Guangxi Massacre. Cannibal acts occurred at public events organized by local Communist Party officials, with people taking part in them in order to prove their revolutionary passion. The writer Zheng Yi documented many of these incidents, especially those in Guangxi, in his 1993 book, Scarlet Memorial.

Pills made of human flesh were said to be used by some Tibetan Buddhists, motivated by a belief that mystical powers were bestowed upon those who consumed Brahmin flesh.

Southeast Asia

In Joshua Oppenheimer's film The Look of Silence, several of the anti-Communist militias active in the Indonesian mass killings of 1965–66 claim that drinking blood from their victims prevented them from going mad.

East Asia

Reports of widespread cannibalism began to emerge from North Korea during the famine of the 1990s and subsequent ongoing starvation. Kim Jong-il was reported to have ordered a crackdown on cannibalism in 1996, but Chinese travellers reported in 1998 that cannibalism had occurred. Three people in North Korea were reported to have been executed for selling or eating human flesh in 2006. Further reports of cannibalism emerged in early 2013, including reports of a man executed for killing his two children for food.

There are competing claims about how widespread cannibalism was in North Korea. While refugees reported that it was widespread, Barbara Demick wrote in her book, Nothing to Envy: Ordinary Lives in North Korea (2010), that it did not seem to be.

Melanesia

The Korowai tribe of south-eastern Papua could be one of the last surviving tribes in the world engaging in cannibalism. A local cannibal cult killed and ate victims as late as 2012.

As in some other Papuan societies, the Urapmin people engaged in cannibalism in war. Notably, the Urapmin also had a system of food taboos wherein dogs could not be eaten and they had to be kept from breathing on food, unlike humans who could be eaten and with whom food could be shared.