Herd immunity (also called herd effect, community immunity, population immunity, or mass immunity) is a form of indirect protection that applies only to contagious diseases. It occurs when a sufficient percentage of a population has become immune to an infection, whether through previous infections or vaccination, thereby reducing the likelihood of infection for individuals who lack immunity.

Once the herd immunity has been reached, disease gradually disappears from a population and may result in eradication or permanent reduction of infections to zero if achieved worldwide. Herd immunity created via vaccination has contributed to the reduction of many diseases.

Effects

Protection of those without immunity

Some individuals either cannot develop immunity after vaccination or for medical reasons cannot be vaccinated. Newborn infants are too young to receive many vaccines, either for safety reasons or because passive immunity renders the vaccine ineffective. Individuals who are immunodeficient due to HIV/AIDS, lymphoma, leukemia, bone marrow cancer, an impaired spleen, chemotherapy, or radiotherapy may have lost any immunity that they previously had and vaccines may not be of any use for them because of their immunodeficiency.

A portion of those vaccinated may not develop long-term immunity. Vaccine contraindications may prevent certain individuals from being vaccinated. In addition to not being immune, individuals in one of these groups may be at a greater risk of developing complications from infection because of their medical status, but they may still be protected if a large enough percentage of the population is immune.

High levels of immunity in one age group can create herd immunity for other age groups. Vaccinating adults against pertussis reduces pertussis incidence in infants too young to be vaccinated, who are at the greatest risk of complications from the disease. This is especially important for close family members, who account for most of the transmissions to young infants. In the same manner, children receiving vaccines against pneumococcus reduces pneumococcal disease incidence among younger, unvaccinated siblings. Vaccinating children against pneumococcus and rotavirus has had the effect of reducing pneumococcus- and rotavirus-attributable hospitalizations for older children and adults, who do not normally receive these vaccines. Influenza (flu) is more severe in the elderly than in younger age groups, but influenza vaccines lack effectiveness in this demographic due to a waning of the immune system with age. The prioritization of school-age children for seasonal flu immunization, which is more effective than vaccinating the elderly, however, has been shown to create a certain degree of protection for the elderly.

For sexually transmitted infections (STIs), high levels of immunity in heterosexuals of one sex induces herd immunity for heterosexuals of both sexes. Vaccines against STIs that are targeted at heterosexuals of one sex result in significant declines in STIs in heterosexuals of both sexes if vaccine uptake in the target sex is high. Herd immunity from female vaccination does not, however, extend to males who have sex with males. High-risk behaviors make eliminating STIs difficult because, even though most infections occur among individuals with moderate risk, the majority of transmissions occur because of individuals who engage in high-risk behaviors. For this reason, in certain populations it may be necessary to immunize high-risk individuals regardless of sex.

Evolutionary pressure and serotype replacement

Herd immunity itself acts as an evolutionary pressure on pathogens, influencing viral evolution by encouraging the production of novel strains, referred to as escape mutants, that are able to evade herd immunity and infect previously immune individuals. The evolution of new strains is known as serotype replacement, or serotype shifting, as the prevalence of a specific serotype declines due to high levels of immunity, allowing other serotypes to replace it.

At the molecular level, viruses escape from herd immunity through antigenic drift, which is when mutations accumulate in the portion of the viral genome that encodes for the virus's surface antigen, typically a protein of the virus capsid, producing a change in the viral epitope. Alternatively, the reassortment of separate viral genome segments, or antigenic shift, which is more common when there are more strains in circulation, can also produce new serotypes. When either of these occur, memory T cells no longer recognize the virus, so people are not immune to the dominant circulating strain. For both influenza and norovirus, epidemics temporarily induce herd immunity until a new dominant strain emerges, causing successive waves of epidemics. As this evolution poses a challenge to herd immunity, broadly neutralizing antibodies and "universal" vaccines that can provide protection beyond a specific serotype are in development.

Initial vaccines against Streptococcus pneumoniae significantly reduced nasopharyngeal carriage of vaccine serotypes (VTs), including antibiotic-resistant types, only to be entirely offset by increased carriage of non-vaccine serotypes (NVTs). This did not result in a proportionate increase in disease incidence though, since NVTs were less invasive than VTs. Since then, pneumococcal vaccines that provide protection from the emerging serotypes have been introduced and have successfully countered their emergence. The possibility of future shifting remains, so further strategies to deal with this include expansion of VT coverage and the development of vaccines that use either killed whole-cells, which have more surface antigens, or proteins present in multiple serotypes.

Eradication of diseases

If herd immunity has been established and maintained in a population for a sufficient time, the disease is inevitably eliminated – no more endemic transmissions occur. If elimination is achieved worldwide and the number of cases is permanently reduced to zero, then a disease can be declared eradicated. Eradication can thus be considered the final effect or end-result of public health initiatives to control the spread of contagious disease. In cases in which herd immunity is compromised, on the contrary, disease outbreaks among the unvaccinated population are likely to occur.

The benefits of eradication include ending all morbidity and mortality caused by the disease, financial savings for individuals, health care providers, and governments, and enabling resources used to control the disease to be used elsewhere. To date, two diseases have been eradicated using herd immunity and vaccination: rinderpest and smallpox. Eradication efforts that rely on herd immunity are currently underway for poliomyelitis, though civil unrest and distrust of modern medicine have made this difficult. Mandatory vaccination may be beneficial to eradication efforts if not enough people choose to get vaccinated.

Free riding

Herd immunity is vulnerable to the free rider problem. Individuals who lack immunity, including those who choose not to vaccinate, free ride off the herd immunity created by those who are immune. As the number of free riders in a population increases, outbreaks of preventable diseases become more common and more severe due to loss of herd immunity. Individuals may choose to free ride or be hesitant to vaccinate for a variety of reasons, including the belief that vaccines are ineffective, or that the risks associated with vaccines are greater than those associated with infection, mistrust of vaccines or public health officials, bandwagoning or groupthinking, social norms or peer pressure, and religious beliefs. Certain individuals are more likely to choose not to receive vaccines if vaccination rates are high enough to convince a person that he or she may not need to be vaccinated, since a sufficient percentage of others are already immune.

Mechanism

Individuals who are immune to a disease act as a barrier in the spread of disease, slowing or preventing the transmission of disease to others. An individual's immunity can be acquired via a natural infection or through artificial means, such as vaccination. When a critical proportion of the population becomes immune, called the herd immunity threshold (HIT) or herd immunity level (HIL), the disease may no longer persist in the population, ceasing to be endemic.

The theoretical basis for herd immunity generally assumes that vaccines induce solid immunity, that populations mix at random, that the pathogen does not evolve to evade the immune response, and that there is no non-human vector for the disease.

Theoretical basis

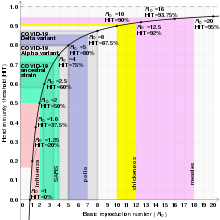

The critical value, or threshold, in a given population, is the point where the disease reaches an endemic steady state, which means that the infection level is neither growing nor declining exponentially. This threshold can be calculated from the effective reproduction number Re, which is obtained by taking the product of the basic reproduction number R0, the average number of new infections caused by each case in an entirely susceptible population that is homogeneous, or well-mixed, meaning each individual is equally likely to come into contact with any other susceptible individual in the population, and S, the proportion of the population who are susceptible to infection, and setting this product to be equal to 1:

S can be rewritten as (1 − p), where p is the proportion of the population that is immune so that p + S equals one. Then, the equation can be rearranged to place p by itself as follows:

With p being by itself on the left side of the equation, it can be renamed as pc, representing the critical proportion of the population needed to be immune to stop the transmission of disease, which is the same as the "herd immunity threshold" HIT. R0 functions as a measure of contagiousness, so low R0 values are associated with lower HITs, whereas higher R0s result in higher HITs. For example, the HIT for a disease with an R0 of 2 is theoretically only 50%, whereas a disease with an R0 of 10 the theoretical HIT is 90%.

When the effective reproduction number Re of a contagious disease is reduced to and sustained below 1 new individual per infection, the number of cases occurring in the population gradually decreases until the disease has been eliminated. If a population is immune to a disease in excess of that disease's HIT, the number of cases reduces at a faster rate, outbreaks are even less likely to happen, and outbreaks that occur are smaller than they would be otherwise. If the effective reproduction number increases to above 1, then the disease is neither in a steady state nor decreasing in incidence, but is actively spreading through the population and infecting a larger number of people than usual.

An assumption in these calculations is that populations are homogeneous, or well-mixed, meaning that every individual is equally likely to come into contact with any other individual, when in reality populations are better described as social networks as individuals tend to cluster together, remaining in relatively close contact with a limited number of other individuals. In these networks, transmission only occurs between those who are geographically or physically close to one another. The shape and size of a network is likely to alter a disease's HIT, making incidence either more or less common.Mathematical models can use contact matrices to estimate the likelihood of encounters and thus transmission.

| Disease | Transmission | R0 | HIT |

|---|---|---|---|

| Measles | Aerosol | 12–18 | 92–94% |

| Chickenpox (varicella) | Aerosol | 10–12 | 90–92% |

| Mumps | Respiratory droplets | 10–12 | 90–92% |

| COVID-19 (see values for specific strains below) | Respiratory droplets and aerosol | 2.9-9.5 | 65–89% |

| Rubella | Respiratory droplets | 6–7 | 83–86% |

| Polio | Fecal–oral route | 5–7 | 80–86% |

| Pertussis | Respiratory droplets | 5.5 | 82% |

| Smallpox | Respiratory droplets | 3.5–6.0 | 71–83% |

| HIV/AIDS | Body fluids | 2–5 | 50–80% |

| SARS | Respiratory droplets | 2–4 | 50–75% |

| Diphtheria | Saliva | 2.6 (1.7–4.3) | 62% (41–77%) |

| Common cold (e.g., rhinovirus) | Respiratory droplets | 2–3 | 50–67% |

| Mpox | Physical contact, body fluids, respiratory droplets, sexual (MSM) | 2.1 (1.1–2.7) | 53% (22–63%) |

| Ebola (2014 outbreak) | Body fluids | 1.8 (1.4–1.8) | 44% (31–44%) |

| Influenza (seasonal strains) | Respiratory droplets | 1.3 (1.2–1.4) | 23% (17–29%) |

| Andes hantavirus | Respiratory droplets and body fluids | 1.2 (0.8–1.6) | 16% (0–36%) |

| Nipah virus | Body fluids | 0.5 | 0% |

| MERS | Respiratory droplets | 0.5 (0.3–0.8) | 0% |

In heterogeneous populations, R0 is considered to be a measure of the number of cases generated by a "typical" contagious person, which depends on how individuals within a network interact with each other. Interactions within networks are more common than between networks, in which case the most highly connected networks transmit disease more easily, resulting in a higher R0 and a higher HIT than would be required in a less connected network. In networks that either opt not to become immune or are not immunized sufficiently, diseases may persist despite not existing in better-immunized networks.

Overshoot

The cumulative proportion of individuals who get infected during the course of a disease outbreak can exceed the HIT. This is because the HIT does not represent the point at which the disease stops spreading, but rather the point at which each infected person infects fewer than one additional person on average. When the HIT is reached, the number of additional infections does not immediately drop to zero. The excess of the cumulative proportion of infected individuals over the theoretical HIT is known as the overshoot.

Boosts

Vaccination

The primary way to boost levels of immunity in a population is through vaccination. Vaccination is originally based on the observation that milkmaids exposed to cowpox were immune to smallpox, so the practice of inoculating people with the cowpox virus began as a way to prevent smallpox. Well-developed vaccines provide protection in a far safer way than natural infections, as vaccines generally do not cause the diseases they protect against and severe adverse effects are significantly less common than complications from natural infections.

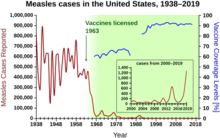

The immune system does not distinguish between natural infections and vaccines, forming an active response to both, so immunity induced via vaccination is similar to what would have occurred from contracting and recovering from the disease. To achieve herd immunity through vaccination, vaccine manufacturers aim to produce vaccines with low failure rates, and policy makers aim to encourage their use. After the successful introduction and widespread use of a vaccine, sharp declines in the incidence of diseases it protects against can be observed, which decreases the number of hospitalizations and deaths caused by such diseases.

Assuming a vaccine is 100% effective, then the equation used for calculating the herd immunity threshold can be used for calculating the vaccination level needed to eliminate a disease, written as Vc. Vaccines are usually imperfect however, so the effectiveness, E, of a vaccine must be accounted for:

From this equation, it can be observed that if E is less than (1 − 1/R0), then it is impossible to eliminate a disease, even if the entire population is vaccinated. Similarly, waning vaccine-induced immunity, as occurs with acellular pertussis vaccines, requires higher levels of booster vaccination to sustain herd immunity. If a disease has ceased to be endemic to a population, then natural infections no longer contribute to a reduction in the fraction of the population that is susceptible. Only vaccination contributes to this reduction. The relation between vaccine coverage and effectiveness and disease incidence can be shown by subtracting the product of the effectiveness of a vaccine and the proportion of the population that is vaccinated, pv, from the herd immunity threshold equation as follows:

It can be observed from this equation that, all other things being equal ("ceteris paribus"), any increase in either vaccine coverage or vaccine effectiveness, including any increase in excess of a disease's HIT, further reduces the number of cases of a disease. The rate of decline in cases depends on a disease's R0, with diseases with lower R0 values experiencing sharper declines.

Vaccines usually have at least one contraindication for a specific population for medical reasons, but if both effectiveness and coverage are high enough then herd immunity can protect these individuals. Vaccine effectiveness is often, but not always, adversely affected by passive immunity, so additional doses are recommended for some vaccines while others are not administered until after an individual has lost his or her passive immunity.

Passive immunity

Individual immunity can also be gained passively, when antibodies to a pathogen are transferred from one individual to another. This can occur naturally, whereby maternal antibodies, primarily immunoglobulin G antibodies, are transferred across the placenta and in colostrum to fetuses and newborns. Passive immunity can also be gained artificially, when a susceptible person is injected with antibodies from the serum or plasma of an immune person.

Protection generated from passive immunity is immediate, but wanes over the course of weeks to months, so any contribution to herd immunity is temporary. For diseases that are especially severe among fetuses and newborns, such as influenza and tetanus, pregnant women may be immunized in order to transfer antibodies to the child. In the same way, high-risk groups that are either more likely to experience infection, or are more likely to develop complications from infection, may receive antibody preparations to prevent these infections or to reduce the severity of symptoms.

Cost–benefit analysis

Herd immunity is often accounted for when conducting cost–benefit analyses of vaccination programs. It is regarded as a positive externality of high levels of immunity, producing an additional benefit of disease reduction that would not occur had no herd immunity been generated in the population. Therefore, herd immunity's inclusion in cost–benefit analyses results both in more favorable cost-effectiveness or cost–benefit ratios, and an increase in the number of disease cases averted by vaccination. Study designs done to estimate herd immunity's benefit include recording disease incidence in households with a vaccinated member, randomizing a population in a single geographic area to be vaccinated or not, and observing the incidence of disease before and after beginning a vaccination program. From these, it can be observed that disease incidence may decrease to a level beyond what can be predicted from direct protection alone, indicating that herd immunity contributed to the reduction. When serotype replacement is accounted for, it reduces the predicted benefits of vaccination.

History

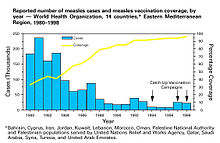

Herd immunity was recognized as a naturally occurring phenomenon in the 1930s when it was observed that after a significant number of children had become immune to measles, the number of new infections temporarily decreased. Mass vaccination to induce herd immunity has since become common and proved successful in preventing the spread of many contagious diseases. Opposition to vaccination has posed a challenge to herd immunity, allowing preventable diseases to persist in or return to populations with inadequate vaccination rates.

The exact herd immunity threshold (HIT) varies depending on the basic reproduction number of the disease. An example of a disease with a high threshold was the measles, with a HIT exceeding 95%.

The term "herd immunity" was first used in 1894 by American veterinary scientist and then Chief of the Bureau of Animal Industry of the US Department of Agriculture Daniel Elmer Salmon to describe the healthy vitality and resistance to disease of well-fed herds of hogs. In 1916 veterinary scientists inside the same Bureau of Animal Industry used the term to refer to the immunity arising following recovery in cattle infected with brucellosis, also known as "contagious abortion." By 1923 it was being used by British bacteriologists to describe experimental epidemics with mice, experiments undertaken as part of efforts to model human epidemic disease. By the end of the 1920s the concept was used extensively - particularly among British scientists - to describe the build up of immunity in populations to diseases such as diphtheria, scarlet fever, and influenza. Herd immunity was recognized as a naturally occurring phenomenon in the 1930s when A. W. Hedrich published research on the epidemiology of measles in Baltimore, and took notice that after many children had become immune to measles, the number of new infections temporarily decreased, including among susceptible children. In spite of this knowledge, efforts to control and eliminate measles were unsuccessful until mass vaccination using the measles vaccine began in the 1960s. Mass vaccination, discussions of disease eradication, and cost–benefit analyses of vaccination subsequently prompted more widespread use of the term herd immunity. In the 1970s, the theorem used to calculate a disease's herd immunity threshold was developed. During the smallpox eradication campaign in the 1960s and 1970s, the practice of ring vaccination, to which herd immunity is integral, began as a way to immunize every person in a "ring" around an infected individual to prevent outbreaks from spreading.

Since the adoption of mass and ring vaccination, complexities and challenges to herd immunity have arisen. Modeling of the spread of contagious disease originally made a number of assumptions, namely that entire populations are susceptible and well-mixed, which is not the case in reality, so more precise equations have been developed. In recent decades, it has been recognized that the dominant strain of a microorganism in circulation may change due to herd immunity, either because of herd immunity acting as an evolutionary pressure or because herd immunity against one strain allowed another already-existing strain to spread. Emerging or ongoing fears and controversies about vaccination have reduced or eliminated herd immunity in certain communities, allowing preventable diseases to persist in or return to these communities.