An empire is a political unit made up of several territories, military outposts, and peoples, "usually created by conquest, and divided between a dominant center and subordinate peripheries". The center of the empire (sometimes referred to as the metropole) exercises political control over the peripheries. Within an empire, different populations have different sets of rights and are governed differently. Narrowly defined, an empire is a sovereign state whose head of state is an emperor or empress; but not all states with aggregate territory under the rule of supreme authorities are called empires or are ruled by an emperor; nor have all self-described empires been accepted as such by contemporaries and historians (the Central African Empire, and some Anglo-Saxon kingdoms in early England being examples).

There have been "ancient and modern, centralized and decentralized, ultra-brutal and relatively benign" empires. An important distinction has been between land empires made up solely of contiguous territories, such as the Austrian Empire or the Russian Empire; and those created by sea-power, which include territories that are remote from the 'home' country of the empire, such as the Carthaginian Empire or the British Empire. Aside from the more formal usage, the word empire can also refer colloquially to a large-scale business enterprise (e.g. a transnational corporation), a political organization controlled by a single individual (a political boss), or a group (political bosses). The concept of empire is associated with other such concepts as imperialism, colonialism, and globalization, with imperialism referring to the creation and maintenance of unequal relationships between nations and not necessarily the policy of a state headed by an emperor or empress. Empire is often used as a term to describe overpowering situations causing displeasure.

Definition

An empire is an aggregate of many separate states or territories under a supreme ruler or oligarchy. This is in contrast to a federation, which is an extensive state voluntarily composed of autonomous states and peoples. An empire is a large polity which rules over territories outside of its original borders.

Definitions of what physically and politically constitutes an empire vary. It might be a state affecting imperial policies or a particular political structure. Empires are typically formed from diverse ethnic, national, cultural, and religious components. 'Empire' and 'colonialism' are used to refer to relationships between a powerful state or society versus a less powerful one; Michael W. Doyle has defined empire as "effective control, whether formal or informal, of a subordinated society by an imperial society".

Tom Nairn and Paul James define empires as polities that "extend relations of power across territorial spaces over which they have no prior or given legal sovereignty, and where, in one or more of the domains of economics, politics, and culture, they gain some measure of extensive hegemony over those spaces to extract or accrue value". Rein Taagepera has defined an empire as "any relatively large sovereign political entity whose components are not sovereign".

The terrestrial empire's maritime analogue is the thalassocracy, an empire composed of islands and coasts which are accessible to its terrestrial homeland, such as the Athenian-dominated Delian League.

Furthermore, empires can expand by both land and sea. Stephen Howe notes that empires by land can be characterized by expansion over terrain, "extending directly outwards from the original frontier" while an empire by sea can be characterized by colonial expansion and empire building "by an increasingly powerful navy".

However, sometimes an empire is only a semantic construction, such as when a ruler assumes the title of "emperor". That polity over which the ruler reigns logically becomes an "empire", despite having no additional territory or hegemony. Examples of this form of empire are the Central African Empire, Mexican Empire, or the Korean Empire proclaimed in 1897 when Korea, far from gaining new territory, was on the verge of being annexed by the Empire of Japan, one of the last to use the name officially. Among the last states in the 20th century known as empires in this sense were the Central African Empire, Ethiopia, Vietnam, Manchukuo, Russia, Germany, and Korea.

Scholars distinguish empires from nation-states. In an empire, there is a hierarchy whereby one group of people (usually, the metropole) has command over other groups of people, and there is a hierarchy of rights and prestige for different groups of people. Josep Colomer distinguished between empires and nation-states in the following way:

- Empires were vastly larger than states

- Empires lacked fixed or permanent boundaries whereas a state had fixed boundaries

- Empires had a "compound of diverse groups and territorial units with asymmetric links with the center" whereas a state had "supreme authority over a territory and population"

- Empires had multi-level, overlapping jurisdictions whereas a state sought monopoly and homogenization

Characteristics

Empires originated as different types of states, although they commonly began as powerful monarchies. Ideas about empires have changed over time, ranging from public approval to distaste. Empires are built out of separate units with some kind of diversity – ethnic, national, cultural, religious – and imply at least some inequality between the rulers and the ruled. Without this inequality, the system would be seen as a commonwealth.

Many empires were the result of military conquest, incorporating the vanquished states into a political union, but imperial hegemony can be established in other ways. The Athenian Empire, the Roman Empire, and the British Empire developed at least in part under elective auspices. The Empire of Brazil declared itself an empire after separating from the Portuguese Empire in 1822. France has twice transitioned from being called the French Republic to being called the French Empire while it retained an overseas empire.

Europeans began applying the designation of "empire" to non-European monarchies, such as the Qing Empire and the Mughal Empire, as well as the Maratha Confederacy, eventually leading to the looser denotations applicable to any political structure meeting the criteria of "imperium". Some monarchies styled themselves as having greater size, scope, and power than the territorial, politico-military, and economic facts support. As a consequence, some monarchs assumed the title of "emperor" (or its corresponding translation, tsar, empereur, kaiser, shah etc.) and renamed their states as "The Empire of ...". Empires were seen as an expanding power, administration, ideas and beliefs followed by cultural habits from place to place. Some empires tended to impose their culture on the subject states to strengthen the imperial structure; others opted for multicultural and cosmopolitan policies. Cultures generated by empires could have notable effects that outlasted the empire itself. Most histories of empires have been hostile, especially if the authors were promoting nationalism. Stephen Howe, although himself hostile, listed positive qualities: the guaranteed stability, security, and legal order for their subjects. They tried to minimize ethnic and religious antagonism inside the empire. The aristocracies that ruled them were often more cosmopolitan and broad-minded than their nationalistic successors.

There are two main ways to establish and maintain an imperial political structure: (i) as a territorial empire of direct conquest and control with force or (ii) as a coercive, hegemonic empire of indirect conquest and control with power. The former method provides greater tribute and direct political control, yet limits further expansion because it absorbs military forces to fixed garrisons. The latter method provides less tribute and indirect control, but avails military forces for further expansion. Territorial empires (e.g. the Macedonian Empire and Byzantine Empire) tend to be contiguous areas. The term, on occasion, has been applied to maritime republics or thalassocracies (e.g. the Athenian and British empires) with looser structures and more scattered territories, often consisting of many islands and other forms of possessions which required the creation and maintenance of a powerful navy. Empires such as the Holy Roman Empire also came together by electing the emperor with votes from member realms through the Imperial election.

History of imperialism

Bronze and Iron Age empires

Stephen Howe writes that with the exception of the Roman, Chinese and "perhaps ancient Egyptian states", early empires seldom survived the death of their founder and were usually limited in scope to conquest and collection of tribute, having little impact on the everyday lives of their subjects.

With the exception of Rome, the periods of dissolution following imperial falls were equally short. Successor states seldom outlived their founders and disappeared in the next and often larger empire. Some empires, like the Neo-Babylonian, Median and Lydian were outright conquered by a larger empire. The historical pattern was not a simple rise-and-fall cycle; rather it was rise, fall, and greater rise, or as Raoul Naroll put it, "expanding pulsation."

Empires were limited in scope to conquest, as Howe observed, but conquest is a considerable scope. Many fought to the death to avoid it or to be liberated from it. Imperial conquests and attempts of conquest significantly contributed to the list of wars by death toll. The imperial impact on subjects can be regarded as "little," but only on those subjects who survived the imperial conquest and rule. We cannot ask the inhabitants of Carthage and Masada, for example, whether empire had little impact on their lives, we seldom hear the voices of subject peoples because history is mostly written by winners. But one rich primary source of the subject population is the Hebrew Prophetic books. The hatred towards the ruling empires expressed in this source makes impression of an impact more serious than estimated by Howe. A classical writer and adherent of empire, Orosius explicitly preferred to avoid the views of subject populations. And another classical Roman patriot, Lucan confessed that "words cannot express how bitterly we are hated" by subject peoples.

The earliest known empire appeared in southern Egypt sometime around 3200 BC. Southern Egypt was divided by three kingdoms each centered on a powerful city. Hierapolis conquered the other two cities over two centuries, and later grew into the country of Egypt. The Akkadian Empire, established by Sargon of Akkad (24th century BC), was an early all-Mesopotamian empire which spread into Anatolia, the Levant and Ancient Iran. This imperial achievement was repeated by Shamshi-Adad I of Assyria and Hammurabi of Babylon in the 19th and 18th centuries BC. In the 15th century BC, the New Kingdom of Ancient Egypt, ruled by Thutmose III, was ancient Africa's major force upon incorporating Nubia and the ancient city-states of the Levant.

c. 1500 BC in China rose the Shang Empire which was succeeded by the Zhou Empire c. 1100 BC. Both equalled or surpassed in territory their contemporary Near Eastern empires such as the Middle Assyrian Empire, Hittite Empire, Egyptian Empire and those of the Mitanni and Elamites. The Zhou Empire dissolved in 770 BC into feudal multi-state system which lasted for five and a half centuries until the universal conquest of Qin in 221 BC. The first empire comparable to Rome in organization was the Neo-Assyrian Empire (916–612 BC). The Median Empire was the first empire within the territory of Persia. By the 6th century BC, after having allied with the Babylonians, Scythians and Cimmerians to defeat the Neo-Assyrian Empire, the Medes were able to establish their own empire, which was the largest of its day and lasted for about sixty years.

Classical period

The Axial Age (mid-First Millennium BC) witnessed unprecedented imperial expansion in the Indo-Mediterranean region and China. The successful and extensive Achaemenid Empire (550–330 BC), also known as the first Persian Empire, covered Mesopotamia, Egypt, parts of Greece, Thrace, the Middle East, much of Central Asia, and North-Western India. It is considered the first great empire in history or the first "world empire". It was overthrown and replaced by the short-lived empire of Alexander the Great. His Empire was succeeded by three Empires ruled by the Diadochi—the Seleucid, Ptolemaic, and Macedonian, which, despite being independent, are called the "Hellenistic Empire" by virtue of their similarities in culture and administration.

Meanwhile, in the western Mediterranean the Empires of Carthage and Rome began their rise. Having decisively defeated Carthage in 202 BC, Rome defeated Macedonia in 200 BC and the Seleucids in 190–189 BC to establish an all-Mediterranean Empire. The Seleucid Empire broke apart and its former eastern part was absorbed by the Parthian Empire. In 30 BC Rome annexed Ptolemaic Egypt.

In India during the Axial Age appeared the Maurya Empire—a geographically extensive and powerful empire, ruled by the Mauryan dynasty from 321 to 185 BC. The empire was founded in 322 BC by Chandragupta Maurya through the help of Chanakya, who rapidly expanded his power westward across central and western India, taking advantage of the disruptions of local powers following the withdrawal by Alexander the Great. By 320 BC, the Maurya Empire had fully occupied northwestern India as well as defeating and conquering the satraps left by Alexander. Under Emperor Ashoka the Great, the Maurya Empire became the first Indian empire to conquer the whole Indian Peninsula — an achievement repeated only twice, by the Gupta and Mughal Empires. In the reign of Ashoka Buddhism spread to become the dominant religion in many parts of the ancient India.

In 221 BC, China became an empire when the State of Qin ended the chaotic Warring States period through its conquest of the other six states and proclaimed the Qin Empire (221–207 BC). The Qin Empire is known for the construction of the Great Wall of China and the Terracotta Army, as well as the standardization of currency, weights, measures and writing system. It laid the foundation for China's first golden age, the Han Empire (202 BC–AD 9, AD 25–220). The Han Empire expanded into Central Asia and established trade through the Silk Road. Confucianism was, for the first time, adopted as an official state ideology. During the reign of the Emperor Wu of Han, the Xiongnu were pacified. By this time, only four empires stretched between the Pacific and the Atlantic: the Han Empire of China, the Kushan Empire, the Parthian Empire of Persia, and the Roman Empire. The collapse of the Han Empire in AD 220 saw China fragmented into the Three Kingdoms, only to be unified once again by the Jin Empire (AD 266–420). The relative weakness of the Jin Empire plunged China into political disunity that would last from AD 304 to AD 589 when the Sui Empire (AD 581–618) reunited China.

The Romans were the first people to invent and embody the concept of empire in their two mandates: to wage war and to make and execute laws. They were the most extensive Western empire until the early modern period, and left a lasting impact on European society. Many languages, cultural values, religious institutions, political divisions, urban centers, and legal systems can trace their origins to the Roman Empire. The Roman Empire governed and rested on exploitative actions. They took slaves and money from the peripheries to support the imperial center. However, the absolute reliance on conquered peoples to carry out the empire's fortune, sustain wealth, and fight wars would ultimately lead to the collapse of the Roman Empire. The Romans were strong believers in what they called their "civilizing mission". This term was legitimized and justified by writers like Cicero who wrote that only under Roman rule could the world flourish and prosper. This ideology, that was envisioned to bring a new world order, was eventually spread across the Mediterranean world and beyond. People started to build houses like Romans, eat the same food, wear the same clothes and engage in the same games. Even rights of citizenship and authority to rule were granted to people not born within Roman territory.

The Latin word imperium, referring to a magistrate's power to command, gradually assumed the meaning "The territory in which a magistrate can effectively enforce his commands", while the term "imperator" was originally an honorific meaning "commander". The title was given to generals who were victorious in battle. Thus, an "empire" may include regions that are not legally within the territory of a state, but are under either direct or indirect control of that state, such as a colony, client state, or protectorate. Although historians use the terms "Republican Period" and "Imperial Period" to identify the periods of Roman history before and after absolute power was assumed by Augustus, the Romans themselves continued to refer to their government as a republic, and during the Republican Period, the territories controlled by the republic were referred to as "Imperium Romanum". The emperor's actual legal power derived from holding the office of "consul", but he was traditionally honored with the titles of imperator (commander) and princeps (first man or, chief). Later, these terms came to have legal significance in their own right; an army calling their general "imperator" was a direct challenge to the authority of the current emperor.

The legal systems of France and its former colonies are strongly influenced by Roman law. Similarly, the United States was founded on a model inspired by the Roman Republic, with upper and lower legislative assemblies, and executive power vested in a single individual, the president. The president, as "commander-in-chief" of the armed forces, reflects the ancient Roman titles imperator princeps. The Roman Catholic Church, founded in the early Imperial Period, spread across Europe, first by the activities of Christian evangelists, and later by official imperial promulgation.

Post-classical period

In Western Asia, the term "Persian Empire" came to denote the Iranian imperial states established at different historical periods of pre–Islamic and post–Islamic Persia.

In East Asia, various Chinese empires (or dynasties) dominated the political, economic and cultural landscapes during this era, the most powerful of which was probably the Tang Empire (618–690, 705–907). Other influential Chinese empires during the post-classical period include the Sui Empire (581–618), the Great Liao Empire, the Song Empire, the Western Xia Empire (1038–1227), the Great Jin Empire (1115–1234), the Western Liao Empire (1124–1218), the Great Yuan Empire (1271–1368), and the Great Ming Empire (1368–1644). During this period, Japan and Korea underwent voluntary Sinicization. The Sui, Tang and Song empires had the world's largest economy and were the most technologically advanced during their time; the Great Yuan Empire was the world's ninth largest empire by total land area; while the Great Ming Empire is famous for the seven maritime expeditions led by Zheng He.

The Ajuran Sultanate was a Somali empire in the medieval times that dominated the Indian Ocean trade. It was a Somali Muslim sultanate that ruled over large parts of the Horn of Africa in the Middle Ages. Through a strong centralized administration and an aggressive military stance towards invaders, the Ajuran Sultanate successfully resisted an Oromo invasion from the west and a Portuguese incursion from the east during the Gaal Madow and the Ajuran-Portuguese wars. Trading routes dating from the ancient and early medieval periods of Somali maritime enterprise were strengthened or re-established, and foreign trade and commerce in the coastal provinces flourished with ships sailing to and coming from many kingdoms and empires in East Asia, South Asia, Southeast Asia, Europe, Middle East, North Africa and East Africa.

In the 7th century, Maritime Southeast Asia witnessed the rise of a Buddhist thallasocracy, the Srivijaya Empire, which thrived for 600 years and was succeeded by the Hindu-Buddhist Majapahit Empire that ruled from the 13th to 15th centuries. In the Southeast Asian mainland, the Hindu-Buddhist Khmer Empire was centered in the city of Angkor and flourished from the 9th to 13th centuries. Following the demise of the Khmer Empire, the Siamese Empire flourished alongside the Burmese and Lan Chang Empires from the 13th through the 18th centuries.

In Southeastern and Eastern Europe, during 917, the Eastern Roman Empire, sometimes called the Byzantine Empire, was forced to recognize the Imperial title of Bulgarian ruler Simeon the Great, who were then called Tsar, the first ruler to hold that precise imperial title. The Bulgarian Empire, established in the region in 680–681, remained a major power in Southeast Europe until its fall in the late 14th century. Bulgaria gradually reached its cultural and territorial apogee in the 9th century and early 10th century under Prince Boris I and Simeon I, when its early Christianization in 864 allowed it to develop into the cultural and literary center of Slavic Europe, as well as one of the largest states in Europe, thus the period is considered the Golden Age of medieval Bulgarian culture. Major events included the development of the Cyrillic script at the Preslav Literary School, declared official in 893, and the establishment of the liturgy in Old Church Slavonic, also called Old Bulgarian.

At the time, in the Medieval West, the title "empire" had a specific technical meaning that was exclusively applied to states that considered themselves the heirs and successors of the Roman Empire. Among these were the "Byzantine Empire", which was the actual continuation of the Eastern portion of the Roman Empire, the Carolingian Empire, the largely Germanic Holy Roman Empire, and the Russian Empire. Yet, these states did not always fit the geographic, political, or military profiles of empires in the modern sense of the word. To legitimise their imperium, these states directly claimed the title of Empire from Rome. The sacrum Romanum imperium (Holy Roman Empire), which lasted from 800 to 1806, claimed to have exclusively comprehended Christian principalities, and was only nominally a discrete imperial state. The Holy Roman Empire was not always centrally-governed, as it had neither core nor peripheral territories, and was not governed by a central, politico-military elite. Hence, Voltaire's remark that the Holy Roman Empire "was neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire" is accurate to the degree that it ignores German rule over Italian, French, Provençal, Polish, Flemish, Dutch, and Bohemian populations, and the efforts of the ninth-century Holy Roman Emperors (i.e., the Ottonians) to establish central control. Voltaire's "nor an empire" observation applies to its late period.

In 1204, after the Fourth Crusade conquered Constantinople, the crusaders established a Latin Empire (1204–1261) in that city, while the defeated Byzantine Empire's descendants established two smaller, short-lived empires in Asia Minor: the Empire of Nicaea (1204–1261) and the Empire of Trebizond (1204–1461). Constantinople was retaken in 1261 by the Byzantine successor state centered in Nicaea, re-establishing the Byzantine Empire until 1453, by which time the Turkish-Muslim Ottoman Empire (ca. 1300–1918), had conquered most of the region. The Ottoman Empire was a successor of the Abbasid Empire and it was the most powerful empire to succeed the Abbasi empires at the time, as well as one of the most powerful empires in the world. They became the successors after the Abbasid Empire fell from the Mongols (Hülegü Khan). The Ottoman Empire centered on modern day Turkey, dominated the eastern Mediterranean, overthrew the Byzantine Empire to claim Constantinople and it would start battering at Austria and Malta, which were countries that were key to central and to south-west Europe respectively — mainly for their geographical location. The reason these occurrences of batterings were so important was because the Ottomans were Muslim, and the rest of Europe was Christian, so there was a sense of religious fighting going on. This was not just a rivalry of East and West but a rivalry between Christians and Muslims. Both the Christians and Muslims had alliances with other countries, and they had problems in them as well. The flows of trade and of cultural influences across the supposed great divide never ceased, so the countries never stopped bartering with each other. These epochal clashes between civilizations profoundly shaped many people's thinking back then, and continues to do so in the present day. Modern hatred against Muslim communities in South-Eastern Europe, mainly in Bosnia and Kosovo, has often been articulated in terms of seeing them as unwelcome residues of this imperialism: in short, as Turks. Moreover, Eastern Orthodox imperialism was not re-established until the coronation of Ivan the Terrible as Emperor of Russia in 1547. Likewise, with the collapse of the Holy Roman Empire in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815), the Austrian Empire (1804–1867) emerged reconstituted as the Empire of Austria-Hungary (1867–1918), having "inherited" the imperium of Central and Western Europe from the losers of said wars.

In the thirteenth century, Genghis Khan expanded the Mongol Empire to be the largest contiguous empire in the world. However, within two generations, the empire was separated into four discrete khanates under Genghis Khan's grandsons. One of them, Kublai Khan, conquered China and established the Yuan dynasty with the imperial capital at Beijing. One family ruled the whole Eurasian land mass from the Pacific to the Adriatic and Baltic Seas. The emergence of the Pax Mongolica had significantly eased trade and commerce across Asia. The Safavid Empire of Iran was also founded.

Early Modern period

The Islamic gunpowder empires started to develop from the 15th century. In the Indian subcontinent, the Delhi Sultanate conquered most of the Indian peninsula and spread Islam across it. It later disintegrated with the establishment of the Bengal, Gujarat, and Bahmani Sultanate. In the 16th century, the Mughal Empire was founded by Timur and Genghis Khan's direct descendant Babur. His successors such Humayun, Akbar, Jahangir and Shah Jahan extended the empire. In the 17th century, Aurangzeb expanded the Mughal Empire, controlling most of the South Asia through Sharia, which became the world's largest economy and leading manufacturing power with a nominal GDP that valued a quarter of world GDP, superior than the combination of Europe's GDP. It has been estimated that the Mughal emperors controlled an unprecedented one-fourth of the world's entire economy and was home to one-fourth of the world's population at the time. After the death of Aurangzeb, which marks the end of the medieval India and the beginning of European invasion in India, the empire was weakened by Nader Shah's invasion.

The Mysore Empire was soon established by Hyder Ali and Tipu Sultan, who allied with Napoleon Bonaparte. Other independent empires were also established, such as those ruled by the Nawabs of Bengal and Nizam of Hyderabad.

In the pre-Columbian Americas, two Empires were prominent—the Azteca in Mesoamerica and Inca in Peru. Both existed for several generations before the arrival of the Europeans. Inca had gradually conquered the whole of the settled Andean world as far south as today Santiago in Chile.

In Oceania, the Tonga Empire was a lonely empire that existed from the Late Middle Ages to the Modern period.

Colonial empires

In the 15th century, Castile (Spain) landing in the so-called "New World" (first, the Americas, and later Australia), along with Portuguese travels around the Cape of Good Hope and along the coast of Africa bordering the southeast Indian Ocean, proved ripe opportunities for the continent's Renaissance-era monarchies to establish colonial empires like those of the ancient Romans and Greeks. In the Old World, colonial imperialism was attempted and established on the Canary Islands and Ireland. These conquered lands and people became de jure subordinates of the empire, rather than de facto imperial territories and subjects. Such subjugation often elicited "client-state" resentment that the empire unwisely ignored, leading to the collapse of the European colonial imperial system in the late 19th through the mid-20th century. Portuguese discovery of Newfoundland in the New World gave way to many expeditions led by England (later Britain), Spain, France, and the Dutch Republic. In the 18th century, the Spanish Empire was at its height because of the great mass of goods taken from conquered territory in the Americas (nowadays Mexico, parts of the United States, the Caribbean, most of Central America, and South America) and the Philippines.

Modern period

The British established their first empire (1583–1783) in North America by colonising lands that made up British America, including parts of Canada, the Caribbean and the Thirteen Colonies. In 1776, the Continental Congress of the Thirteen Colonies declared itself independent from the British Empire, thus beginning the American Revolution. Britain turned towards Asia, the Pacific, and later Africa, with subsequent exploration and conquests leading to the rise of the Second British Empire (1783–1815), which was followed by the Industrial Revolution and Britain's Imperial Century (1815–1914). It became the largest empire in world history, encompassing one quarter of the world's land area and one fifth of its population. The impacts of this period are still prominent in the current age "including widespread use of the English language, belief in Protestant religion, economic globalization, modern precepts of law and order, and representative democracy."

The Great Qing Empire of China (1644–1912) was the fourth largest empire in world history by total land area, and laid the foundation for the modern territorial claims of both the People's Republic of China and the Republic of China. Apart from having direct control over much of East Asia, the empire also exerted domination over other states through the Chinese tributary system. The multiethnic and multicultural nature of the Great Qing Empire was crucial to the subsequent birth of the nationalistic concept of zhonghua minzu. The empire reached its peak during the reign of the Qianlong Emperor, after which the empire entered a period of prolonged decline, culminating in its collapse as a result of the Xinhai Revolution.

The Ashanti Empire (or Confederacy), also Asanteman (1701–1896), was a West African state of the Ashanti, the Akan people of the Ashanti Region, Akanland in modern-day Ghana. The Ashanti (or Asante) were a powerful, militaristic and highly disciplined people in West Africa. Their military power, which came from effective strategy and an early adoption of European firearms, created an empire that stretched from central Akanland (in modern-day Ghana) to present day Benin and Ivory Coast, bordered by the Dagomba kingdom to the north and Dahomey to the east. Due to the empire's military prowess, sophisticated hierarchy, social stratification and culture, the Ashanti empire had one of the largest historiographies of any indigenous Sub-Saharan African political entity.

The Sikh Empire (1799–1846) was established in the Punjab region of India. The empire collapsed when its founder, Ranjit Singh, died and its army fell to the British. During the same period, the Maratha Empire (also known as the Maratha Confederacy) was a Hindu state located in present-day India. It existed from 1674 to 1818, and at its peak, the empire's territories covered much of Southern Asia. The empire was founded and consolidated by Shivaji. After the death of Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb, it expanded greatly under the rule of the Peshwas. In 1761, the Maratha army lost the Third Battle of Panipat, which halted the expansion of the empire. Later, the empire was divided into a confederacy of states which, in 1818, were lost to the British during the Anglo-Maratha wars.

France was a dominant empire possessing many colonies in various locations around the world. During Louis XIV's long reign, from 1643 to 1715, France was the leading European power as Europe's most populous, richest and powerful country. The Empire of the French (1804–1814), also known as the Greater French Empire or First French Empire but more commonly known as the Napoleonic Empire, was also the dominant power of much of continental Europe. It ruled over 90 million people and was the sole power in Europe if not the world; Britain was the only main rival during the early 19th century. From the 16th to the 17th centuries, the First French colonial empire’s total area at its peak in 1680 was over 10 million km2 (3.9 million sq mi), the second largest empire in the world at the time behind only the Spanish Empire. It had many possessions around the world, mainly in the Americas, Asia and Africa. At its peak in 1750, French India had an area of 1.5 million km2 and a total population of 100 million people and was the most populous colony under French rule. In the 19th and 20th centuries, the colonial empire of France was the second largest in the world behind the British Empire. The French colonial empire extended over 13.5 million km2 (5.2 million sq mi) of land at its height in the 1920s and 1930s with a totaled population of 150 million people. Including metropolitan France, the total amount of land under French sovereignty reached 13.5 million km2 (5.2 million sq mi) at the time, which is 10.0% of the Earth's total land area. The total area of the French colonial empire, with the first (mainly in the Americas and Asia) and second (mainly in Africa and Asia), the French colonial empires combined, reached 24 million km2 (9.3 million sq mi), the second largest in the world (the first being the British Empire).

The Empire of Brazil (1822–1889) was the only South American modern monarchy, established by the heir of the Portuguese Empire as an independent nation eventually became an emerging international power. The new country was huge but sparsely populated and ethnically diverse. In 1889 the monarchy was overthrown in a sudden coup d'état led by a clique of military leaders whose goal was the formation of a republic.

The German Empire (1871–1918), another "heir to the Holy Roman Empire", arose in 1871.

Fall of empires

Roman Empire

The fall of the western half of the Roman Empire is seen as one of the most pivotal points in all of human history. This event traditionally marks the transition from classical civilization to the birth of Europe. The Roman Empire started to decline at the end of the reign of the last of the Five Good Emperors, Marcus Aurelius in 161–180 A.D. There is still a debate over the cause of the fall of one of the largest empires in history. Piganiol argues that the Roman Empire under its authority can be described as "a period of terror", holding its imperial system accountable for its failure. Another theory blames the rise of Christianity as the cause, arguing that the spread of certain Christian ideals caused internal weakness of the military and state. In his book The Fall of the Roman Empire, Peter Heather contends that there are many factors, including issues of money and manpower, which produce military limitations and culminate in the Roman army's inability to effectively repel invading barbarians at the frontier. The Western Roman economy was already stretched to its limit in the 4th and 5th centuries C.E. due to continual conflict and loss of territory which, in turn, generated loss of revenue from the tax base. There was also the looming presence of the Persians which, at any time, took a large percentage of the fighting force's attention. At the same time the Huns, a nomadic warrior people from the steppes of Asia, are also putting extreme pressure on the German tribes outside of the Roman frontier, which gave the German tribes no other choice, geographically, but to move into Roman territory. At this point, without increased funding, the Roman army could no longer effectively defend its borders against major waves of Germanic tribes. This inability is illustrated by the crushing defeat at Adrianople in 378 C.E. and, later, the Crossing of the Rhine in 406 C.E.

Transition from empire

In time, an empire may change from one political entity to another. For example, the Holy Roman Empire, a German re-constitution of the Roman Empire, metamorphosed into various political structures (i.e., federalism), and eventually, under Habsburg rule, re-constituted itself in 1804 as the Austrian Empire, an empire of much different politics and scope, which in turn became the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1867. The Roman Empire, perennially reborn, also lived on as the Byzantine Empire (Eastern Roman Empire) – temporarily splitting into the Latin Empire, the Empire of Nicaea and the Empire of Trebizond before its remaining territory and centre became part of the Ottoman Empire. A similarly persistent concept of empire saw the Mongol Empire become the Khanate of the Golden Horde, the Yuan Empire of China, and the Ilkhanate before resurrection as the Timurid Empire and as the Mughal Empire. After 1945 the Empire of Japan retained its Emperor but lost its colonial possessions and became the State of Japan. Despite the semantic reference to imperial power, Japan is a de jure constitutional monarchy, with a homogeneous population of 127 million people that is 98.5 percent ethnic Japanese, making it one of the largest nation-states.

An autocratic empire can become a republic (e.g., the Central African Empire in 1979), or it can become a republic with its imperial dominions reduced to a core territory (e.g., Weimar Germany shorn of the German colonial empire (1918–1919), or the Ottoman Empire (1918–1923)). The dissolution of the Austro-Hungarian Empire after 1918 provides an example of a multi-ethnic superstate broken into constituent nation-oriented states: the republics, kingdoms, and provinces of Austria, Hungary, Transylvania, Croatia, Slovenia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Czechoslovakia, Ruthenia, Galicia, et al. In the aftermath of World War I the Russian Empire also broke up and became reduced to the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic (RSFSR) before re-forming as the USSR (1922–1991) – sometimes seen as the core of a Soviet Empire. The latter also disintegrated in 1989–91.

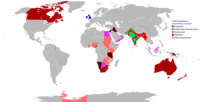

After the Second World War (1939–1945), the deconstruction of colonial empires quickened and became commonly known as decolonisation. The British Empire evolved into a loose, multinational Commonwealth of Nations, while the French colonial empire metamorphosed to a Francophone commonwealth. The same process happened to the Portuguese Empire, which evolved into a Lusophone commonwealth, and to the former territories of the extinct Spanish Empire, which alongside the Lusophone countries of Portugal and Brazil, created an Ibero-American commonwealth. France returned the French territory of Kwang-Chou-Wan to China in 1946. The British gave Hong Kong back to China in 1997 after 150 years of rule. The Portuguese territory of Macau reverted to China in 1999. Macau and Hong Kong did not become part of the provincial structure of China; they have autonomous systems of government as Special Administrative Regions of the People's Republic of China.

France still governs overseas territories (French Guiana, Martinique, Réunion, French Polynesia, New Caledonia, Saint Martin, Saint-Pierre-et-Miquelon, Guadeloupe, French Southern and Antarctic Lands (TAAF), Wallis and Futuna, Saint Barthélemy, and Mayotte), and exerts hegemony in Francafrique ("French Africa"; 29 francophone countries such as Chad, Rwanda, etc.). Fourteen British Overseas Territories remain under British sovereignty. Fifteen countries of the Commonwealth of Nations share their head of state, King Charles III, as Commonwealth realms.

Contemporary usage

United States of America

Contemporaneously, the concept of empire is politically valid, yet is not always used in the traditional sense. One of widely discussed cases is the United States. Characterizing aspects of the US in regards to its territorial expansion, foreign policy, and its international behavior as "American Empire" is common. The term "American Empire" refers to the United States' cultural ideologies and foreign policy strategies. The term is most commonly used to describe the U.S.'s status since the 20th century, but it can also be applied to the United States' world standing before the rise of nationalism in the 20th century. The US itself was at one point a colony in the British Empire. However, founding fathers such as George Washington noted after the Revolution that the US was an empire in its infancy, and others like Thomas Jefferson agreed, describing the constitution as the perfect foundation for an "extensive Empire". Jefferson in the 1780s while awaiting the fall of the Spanish empire, said: "till our population can be sufficiently advanced to gain it from them piece by piece".

Even so, the ideology that the US was founded on anti-imperialist principles has prevented many from acknowledging America's status as an empire. This active rejection of imperialist status is not limited to high-ranking government officials, as it has been ingrained in American society throughout its entire history. As David Ludden explains, "journalists, scholars, teachers, students, analysts, and politicians prefer to depict the U.S. as a nation pursuing its own interests and ideals". This often results in imperialist endeavors being presented as measures taken to enhance state security. Ludden explains this phenomenon with the concept of "ideological blinders", which he says prevent American citizens from realizing the true nature of America's current systems and strategies. These "ideological blinders" that people wear have resulted in an "invisible" American empire of which most American citizens are unaware. Besides its anti-imperialist principles, the United States is not traditionally recognized as an empire, because the U.S. adopted a different political system from those that previous empires had used.

Despite the anti-imperial ideology and systematic differences, the political objectives and strategies of the United States government have been quite similar to those of previous empires. Throughout the 19th century, the United States government attempted to expand its territory by any means necessary. Regardless of the supposed motivation for this constant expansion, all of these land acquisitions were carried out by imperialistic means. This was done by financial means in some cases, and by military force in others. Most notably, the Louisiana Purchase (1803), the Texas Annexation (1845), and the Mexican Cession (1848) highlight the imperialistic goals of the United States during this "modern period" of imperialism. The U.S. government has stopped adding additional territories, where they permanently and politically take over since the early 20th century, and instead have established 800 military bases as their outposts. With this overt but subtle military control of other countries, scholars consider U.S. foreign policy strategies to be imperialistic. Academic Krishna Kumar argues that the distinct principles of nationalism and imperialism may result in common practice; that is, the pursuit of nationalism can often coincide with the pursuit of imperialism in terms of strategy and decision making. Stuart Creighton Miller posits that the public's sense of innocence about Realpolitik (politics based on practical considerations, rather than ideals) impacts popular recognition of US imperial conduct since it governed other countries via surrogates. These surrogates were domestically weak, right-wing governments that would collapse without US support.

Former President G. W. Bush's Secretary of Defense, Donald Rumsfeld, said: "We don't seek empires. We're not imperialistic; we never have been." This was said in the context of the international opposition to the Iraq War led by the United States in manner widely regarded as imperial. In his book review of Empire (2000) by Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri, Mehmet Akif Okur posits that since the September 11 attacks in the United States, the international relations determining the world's balance of power (political, economic, military) have been altered. With the 2003 invasion of Iraq underway, historian Sidney Lens argued that, from its inception, the US has used every means available to dominate foreign peoples and states. The same time, Eliot A. Cohen suggested: "The Age of Empire may indeed have ended, but then an age of American hegemony has begun, regardless of what one calls it." Some scholars did not bother how to call it: "When it walks like a duck, talks like a duck, it's a duck."

European Union

Mehmet Akif Okur finds trends in political science that perceive the contemporary world's order via the re-territorialization of political space, the re-emergence of classical imperialist practices (such as the duality between those who are "inside" and those who are "outside"), the deliberate weakening of international organizations, the restructured international economy, economic nationalism, the expanded arming of most countries, the proliferation of nuclear weapon capabilities and the politics of identity emphasizing a state's subjective perception of its place in the world, as a nation and as a civilization. These changes constitute the "Age of Nation Empires". Nation-empire regionalism claims sovereignty over their respective (regional) political (social, economic, ideologic), cultural, and military spheres and denotes the return of geopolitical power from global power blocs to regional power blocs. The European Union is one such power bloc.

Since the European Union was formed as a polity in 1993, it has established its own currency, its own citizenship, established discrete military forces, and exercises its limited hegemony in the Mediterranean, eastern parts of Europe, Sub-Saharan Africa, and Asia. The big size and high development index of the EU economy often has the ability to influence global trade regulations in its favor. The political scientist Jan Zielonka suggests that this behavior is imperial because it coerces its neighbouring countries into adopting its European economic, legal, and political structures. Tony Benn, a left-wing Labour Party MP of the United Kingdom, opposed the European integration policies of the European Union by saying, "I think they're (the European Union) building an empire there, they want us (the United Kingdom) to be a part of their empire and I don't want that."

Russia

In the aftermath of the annexation of Crimea, political scientist Agnia Grigas argued that Moscow pursues the policy of "reimperialization." Two days after the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine, historian specializing on empires, Niall Ferguson, interpreted the policy of Putin as an attempt to bring back the tsarist Russian Empire. By this time, the "neo-imperialism," or "neo-imperial ambitions" of Russia became widely claimed. When Vladimir Putin denies the reality of the Ukrainian state, says another historian of empires Timothy Snyder, he is speaking the familiar language of empire. For five hundred years, European conquerors saw themselves as actors with purpose, and the colonized as instruments to realize the imperial vision.

Vladimir Putin himself used to state: "For Russia to survive, it must remain an empire." In June 2022, on the 350 anniversary of the birth of the 18th-century Russian tsar Peter the Great, Putin has compared himself to him associating their twin historic quests to win back Russian lands. For critics this association implied that Putin's "complaints about historical injustice, eastward NATO expansion, and other grievances with the west were all a façade for a traditional war of conquest" and imperialism. "After months of denials that Russia is driven by imperial ambitions in Ukraine, Putin appeared to embrace that mission." On the same occasion, Mykhailo Podolyak, an adviser to the Ukrainian government, suggested Russia's "de-imperialization," instead of Russia's official war aim of "de-Nazification" of Ukraine.

Later that year, Anne Applebaum approached the new Russian Empire as a fact and opined that this Empire must be defeated. Other pundits described the new Russian Empire as a failed attempt because Russia failed to annex the whole of Ukraine.

Timeline of empires

The chart below shows a timeline of polities that have been called empires. Dynastic changes are marked with a white line.

- The Roman Empire's timeline listed below includes the Western and Eastern portion.

- The Empires of Nicaea and Trebizond were Byzantine successor states.

- The Empire of Bronze Age Egypt is not included in the graph. Established by Narmer circa 3000 BC, it lasted as long as China until it was conquered by Achaemenid Persia in 525 BC.

- Japan is presented for the period of its overseas Empire (1895–1945). The original Japanese Empire of "the Eight Islands" would be third persistent after Egypt and China.

- Many Indian empires are also included, though only Mauryans, Guptas, Delhi Sultans, Mughals, and Marathas ruled for large periods in India.

Theoretical research

Empire versus nation state

Empires have been the dominant international organization in world history:

The fact that tribes, peoples, and nations have made empires points to a fundamental political dynamic, one that helps explain why empires cannot be confined to a particular place or era but emerged and reemerged over thousands of years and on all continents.

Empires ... can be traced as far back as the recorded history goes; indeed, most history is the history of empires ... It is the nation-state—an essentially 19th-century ideal—that is the historical novelty and that may yet prove to be the more ephemeral entity.

Our field's fixation on the Westphalian state has tended to obscure the fact that the main actors in global politics, for most of time immemorial, have been empires rather than states ... In fact, it is a very distorted view of even the Westphalian era not to recognize that it was always at least as much about empires as it was states. Almost all of the emerging European states no sooner began to consolidate than they were off on campaigns of conquest and commerce to the farthest reaches of the globe... Ironically, it was the European empires that carried the idea of the sovereign territorial state to the rest of the world ...

Empire has been the historically predominant form of order in world politics. Looking at a time frame of several millennia, there was no global anarchic system until the European explorations and subsequent imperial and colonial ventures connected disparate regional systems, doing so approximately 500 years ago. Prior to this emergence of a global-scope system, the pattern of world politics was characterized by regional systems. These regional systems were initially anarchic and marked by high levels of military competition. But almost universally, they tended to consolidate into regional empires ... Thus it was empires—not anarchic state systems—that typically dominated the regional systems in all parts of the world ... Within this global pattern of regional empires, European political order was distinctly anomalous because it persisted so long as an anarchy.

Similarly, Anthony Pagden, Eliot A. Cohen, Jane Burbank and Frederick Cooper estimate that "empires have always been more frequent, more extensive political and social forms than tribal territories or nations have ever been." Many empires endured for centuries, while the age of the ancient Egyptian, Chinese and Japanese Empires is counted in millennia. "Most people throughout history have lived under imperial rule."

Empires have played a long and critical part in human history ... [Despite] efforts in words and wars to put national unity at the center of political imagination, imperial politics, imperial practices, and imperial cultures have shaped the world we live in ... Rome was evoked as a model of splendor and order into the Twentieth century and beyond... By comparison, the nation-state appears as a blip on the historical horizon, a state form that emerged recently from under imperial skies and whose hold on the world's political imagination may well prove partial or transitory... The endurance of empire challenges the notion that the nation-state is natural, necessary, and inevitable ...

Political scientist Hedley Bull wrote that "in the broad sweep of human history ... the form of states system has been the exception rather than the rule". His colleague Robert Gilpin confirmed this conclusion for the pre-modern period:

The history of interstate relations was largely that of successive great empires. The pattern of international political change during the millennia of the pre-modern era has been described as an imperial cycle ... World politics was characterized by the rise and decline of powerful empires, each of which in turn unified and ordered its respective international system. The recurrent pattern in every civilization of which we have knowledge was for one state to unify the system under its imperial domination. The propensity toward universal empire was the principal feature of pre-modern politics.

Historian Michael Doyle who undertook an extensive research on empires extended the observation into the modern era:

Empires have been the key actors in world politics for millennia. They helped create the interdependent civilizations of all the continents ... Imperial control stretches through history, many say, to the present day. Empires are as old as history itself ... They have held the leading role ever since.

The author of The Idea of Nationalism: A Study in Its Origins and Background, Hans Kohn, acknowledged that it was the opposite idea—of imperialism—that was, perhaps, the most influential single idea for two millennia, the ordering of human society through unified dominion and common civilization. Yet a century ago, most of the world was ruled by persons who proudly proclaimed themselves Emperors and were proud of their Empires. Of the great powers, only the United States and France were republics.

Universal empire

Expert on warfare Quincy Wright generalized on what he called "universal empire"—empire unifying all the contemporary system:

Balance of power systems have in the past tended, through the process of conquest of lesser states by greater states, towards reduction in the number of states involved, and towards less frequent but more devastating wars, until eventually a universal empire has been established through the conquest by one of all those remaining.

German Sociologist Friedrich Tenbruck finds that the macro-historic process of imperial expansion gave rise to global history in which the formations of universal empires were most significant stages. A later group of political scientists, working on the phenomenon of the current unipolarity, in 2007 edited research on several pre-modern civilizations by experts in respective fields. The overall conclusion was that the balance of power was inherently unstable order and usually soon broke in favor of imperial order. Yet before the advent of the unipolarity, world historian Arnold Toynbee and political scientist Martin Wight had drawn the same conclusion with an unambiguous implication for the modern world:

When this [imperial] pattern of political history is found in the New World as well as in the Old World, it looks as if the pattern must be intrinsic to the political history of societies of the species we call civilizations, in whatever part of the world the specimens of this species occur. If this conclusion is warranted, it illuminates our understanding of civilization itself.

Most states systems have ended in universal empire, which has swallowed all the states of the system. The examples are so abundant that we must ask two questions: Is there any states system which has not led fairly directly to the establishment of a world empire? Does the evidence rather suggest that we should expect any states system to culminate in this way? ... It might be argued that every state system can only maintain its existence on the balance of power, that the latter is inherently unstable, and that sooner or later its tensions and conflicts will be resolved into a monopoly of power.

The earliest thinker to approach the phenomenon of universal empire from a theoretical point of view was Polybius (2:3):

In previous times events in the world occurred without impinging on one another ... [Then] history became a whole, as if a single body; events in Italy and Libya came to be enmeshed with those in Asia and Greece, and everything gets directed towards one single goal.

Johann Gottlieb Fichte, having witnessed the battle at Jena in 1806 when Napoleon overwhelmed Prussia, described what he perceived as a deep historical trend:

There is necessary tendency in every cultivated State to extend itself generally ... Such is the case in Ancient History ... As the States become stronger in themselves and cast off that [Papal] foreign power, the tendency towards a Universal Monarchy over the whole Christian World necessarily comes to light ... This tendency ... has shown itself successively in several States which could make pretensions to such a dominion, and since the fall of the Papacy, it has become the sole animating principle of our History ... Whether clearly or not—it may be obscurely—yet has this tendency lain at the root of the undertakings of many States in Modern Times ... Although no individual Epoch may have contemplated this purpose, yet is this the spirit which runs through all these individual Epochs, and invisibly urges them onward.

Fichte's later compatriot, Geographer Alexander von Humboldt, in the mid-Nineteenth century observed a macro-historic trend of imperial growth in both Hemispheres: "Men of great and strong minds, as well as whole nations, acted under influence of one idea, the purity of which was utterly unknown to them." The imperial expansion filled the world c. 1900. Two famous contemporary observers—Frederick Turner and Halford Mackinder described the event and drew implications, the former predicting American overseas expansion and the latter stressing that the world empire is now in sight.

In 1870, Argentine diplomat, jurist and political theorist Juan Bautista Alberdi described imperial consolidation. As von Humboldt, he found this trend unplanned and irrational but evident beyond doubt in the "unwritten history of events." He linked this trend to the recent Evolution theory: Nations gravitate towards the formation of a single universal society. The laws that lead the nations in that direction are the same natural laws that has formed societies and are part of evolution. These evolutionary laws exist disregarding whether men recognize them.

Similarly, Friedrich Ratzel observed that the "drive toward the building of continually larger states continues throughout the entirety of history" and is active in the present. He drew "Seven Laws of Expansionism". His seventh law stated: "The general trend toward amalgamation transmits the tendency of territorial growth from state to state and increases the tendency in the process of transmission." He commented on this law to make its meaning clear: "There is on this small planet sufficient space for only one great state."

Two other contemporaries—Kang Youwei and George Vacher de Lapouge—stressed that imperial expansion cannot indefinitely proceed on the definite surface of the globe and therefore world empire is imminent. Kang Youwei in 1885 believed that the imperial trend will culminate in the contest between Washington and Berlin and Vacher de Lapouge in 1899 estimated that the final contest will be between Russia and America in which America is likely to triumph.

The above envisaged contests indeed took place, known to us as World War I and II. Writing during the First, Oswald Spengler in The Decline of the West compared two emergences of universal empires and implied for the modern world: The Chinese League of States failed as well as the Taoist idea of intellectual self-disarmament. The Chinese states defended their last independence with bitterness but in vain. Also in vain Rome attempted to avoid conquest of the Hellenistic east. Imperialism is so necessary a product of any civilization that when a strongest people refuse to assume the role of master, it is pushed into it. It is the same with us. The Hague Conference of 1907 was the prelude of World War, the Washington Conference of 1921 will have been that of other wars. Napoleon introduced the idea of military world empire different from the preceding European maritime empires. The contest "for the heritage of the whole world" will culminate "within two generations" (from 1922). The destinies of small states are "without importance to the great march of things." The strongest race will win and seize the management of the world.

Writing during the next World War, political scientists Derwent Whittlesey, Robert Strausz-Hupé and John H. Herz concluded: "Now that the earth is at last parceled out, consolidation has commenced." In "this world of fighting superstates there could be no end to war until one state had subjected all others, until world empire had been achieved by the strongest. This undoubtedly is the logical final stage in the geopolitical theory of evolution."

The world is no longer large enough to harbor several self-contained powers ... The trend toward world domination or hegemony of a single power is but the ultimate consummation of a power-system engrafted upon an otherwise integrated world.

Writing in the last year of the War, American theologian Parley Paul Wormer, German historian Ludwig Dehio, and Hungarian-born writer Emery Reves drew similar conclusions. Fluctuating but persistent movement occurred through the centuries toward ever greater unity. The forward movement toward ever larger unities continues and there is no reason to conclude that it has come to an end. More likely, the greatest convergence of all time is at hand. "Possibly this is the deeper meaning of the savage world conflicts" of the 20th century.

[T]he old European tendency toward division is now being thrust aside by the new global trend toward unification. And the onrush of this trend may not come to rest until it has asserted itself throughout our planet ... The global order still seems to be going through its birth pangs ... With the last tempest barely over, a new one is gathering.

The famous Anatomy of Peace by Reves, written and published in 1945, supposed that without the industrial power of the United States, Hitler already might have established world empire. Proposing world federalism, the book warned: Every dynamic force, every economic and technological reality, every "law of history" and logic "indicates that we are on the verge of a period of empire building," which is "the last phase of the struggle for the conquest of the world." As an elimination contest, one of the three remaining powers or a combination "will achieve by force that unified control made mandatory by the times we live in… Anyone of three, by defeating the other two, would conquer and rule the world." If we fail to institute a unified control over the world in democratic way, the "iron law of history" would compel us to wage wars until world empire is finally attained through conquest. Since the former way is improbable due human blindness, we should precipitate the unification by conquest as quickly as possible and start the restoration of human liberties within the world empire.

Atomic bomb and empire

Reves added "Postscript" to the Anatomy, opening: "A few weeks after the publication of this book, the first atomic bomb exploded over the city of Hiroshima…" This new physical fact however has changed nothing in the political situation. The world empire remains inevitable and nothing else in the book would have been said differently had it been written after August 6, 1945. Not much chance we have to establish world government before the next horrible war between the two superpowers and whoever is victorious would establish the world empire. The book sold an exceptional 800,000 copies in thirty languages, was endorsed by Albert Einstein and numerous other prominent figures, and in 1950 Reves was nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

The year after the War and in the first year of the nuclear age, Einstein and British philosopher Bertrand Russell, known as prominent pacifists, outlined for the near future a perspective of world empire (world government established by force). Einstein believed that, unless world government is established by agreement, an imperial world government would come by war or wars. Russell expected a third World War to result in a world government under the empire of the United States. Three years later, another prominent pacifist, theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, generalized on the ancient Empires of Egypt, Babylon, Persia and Greece to imply for the modern world: "The analogy in present global terms would be the final unification of the world through the preponderant power of either America or Russia, whichever proved herself victorious in the final struggle."

Russian colleague of Russell and Niebuhr, Georgy Fedotov, wrote in 1945: All empires are but stages on the way to the sole empire which must swallow all others. The only question is who will build it and on which foundations. Universal unity is the only alternative to annihilation. Unity by conference is utopian but unity by conquest by the strongest power is not and probably the uncompleted in this War will be completed in the next. "Pax Atlantica" is the best of possible outcomes.

Originally drafted as a secret study for the Office of Strategic Services (the precursor of the CIA) in 1944 and published as a book three years later, The Struggle for the World... by James Burnham concludes: If either of the two Superpowers wins, the result would be a universal empire which in our case would also be a world empire. The historical stage for a world empire had already been set prior to and independently of the discovery of atomic weapons but these weapons make a world empire inevitable and imminent. "The atomic weapons ... will not permit the world to wait." Only a world empire can establish monopoly on atomic weapons and thus guarantee the survival of civilization. A world empire "is in fact the objective of the Third World War which, in its preliminary stages, has already began". The issue of a world empire "will be decided, and in our day. In the course of the decision, both of the present antagonists may, it is true, be destroyed, but one of them must be."

The next year, world historian Crane Brinton similarly supposed that the bomb may in the hands of a very skillful and lucky nation prove to be the weapon that permits that nation to unify the world by imperial conquest, to do what Napoleon and Hitler failed to do. Combined with other "wonders of science," it would permit a quick and easy conquest of the world. In 1951, Hans Morgenthau concluded that the "best" outcome of World War III would be world empire:

Today war has become an instrument of universal destruction, an instrument that destroys the victor and the vanquished ... At worst, victor and loser would be undistinguishable under the leveling impact of such a catastrophe ... At best, the destruction on one side would not be quite as great as on the other; the victor would be somewhat better off than the loser and would establish, with the aid of modern technology, his domination over the world.

Expert on earlier civilizations, Toynbee, further developed the subject of World War III leading to world empire:

The outcome of the Third World War ... seemed likely to be the imposition of an ecumenical peace of the Roman kind by the victor whose victory would leave him with a monopoly on the control of atomic energy in his grasp ... This denouement was foreshadowed, not only by present facts, but by historical precedents, since, in the histories of other civilizations, the time of troubles had been apt to culminate in the delivery of a knock-out blow resulting in the establishment of a universal state ...

The year this volume of A Study of History was published, US Secretary of State John Foster Dulles announced "a knock-out blow" as an official doctrine, a detailed Plan was elaborated and Fortune magazine mapped the design. Section VIII, "Atomic Armaments", of the famous National Security Council Report 68 (NSC 68), approved by President Harry Truman in 1951, uses the term "blow" 17 times, mostly preceded by such adjectives as "powerful", "overwhelming", or "crippling". Another term applied by the strategists was "Sunday punch".

Having modeled the rise of the world empire on the cases of previous empires, Toynbee noted that, by contrast, the modern ultimate "blow" would be atomic. But he remains optimistic: No doubt, the modern world has far greater capacity to reconstruct than the earlier civilizations had.

A pupil of Toynbee, William McNeill, associated with the case of ancient China, which "put a quietus upon the disorders of the warring states by erecting an imperial bureaucratic structure ... The warring states of the Twentieth century seem headed for a similar resolution of their conflicts." The ancient "resolution" McNeill evoked was one of the most sweeping universal conquests in world history, performed by Qin in 230–221 BC. Chinese classic Sima Qian (d. 86 BC) described the event (6:234): "Qin raised troops on a grand scale" and "the whole world celebrated a great bacchanal". Herman Kahn of the RAND Corporation criticized an assembled group of SAC officers for their war plan (SIOP-62). He did not use the term bacchanal but he coined on the occasion an associating word: "Gentlemen, you do not have a war plan. You have a war orgasm!" History did not completely repeat itself but it passed close.

Circumscription theory

According to the circumscription theory of Robert Carneiro, "the more sharply circumscribed area, the more rapidly it will become politically unified." The Empires of Egypt, China and Japan are named the most durable political structures in human history. Correspondingly, these are the three most circumscribed civilizations in human history. The Empires of Egypt (established by Narmer c. 3000 BC) and China (established by Cheng in 221 BC) endured for over two millennia. German Sociologist Friedrich Tenbruck, criticizing the Western idea of progress, emphasized that China and Egypt remained at one particular stage of development for millennia. This stage was universal empire. The development of Egypt and China came to a halt once their empires "reached the limits of their natural habitat". Sinology does not recognize the Eurocentric view of the "inevitable" imperial fall; Egyptology and Japanology pose equal challenges.

Carneiro explored the Bronze Age civilizations. Stuart J. Kaufman, Richard Little and William Wohlforth researched the next three millennia, comparing eight civilizations. They conclude: The "rigidity of the borders" contributed importantly to hegemony in every concerned case. Hence, "when the system's borders are rigid, the probability of hegemony is high".

The circumscription theory was stressed in the comparative studies of the Roman and Chinese Empires. The circumscribed Chinese Empire recovered from all falls, while the fall of Rome, by contrast, was fatal. "What counteracted this [imperial] tendency in Europe ... was a countervailing tendency for the geographical boundaries of the system to expand." If "Europe had been a closed system, some great power would eventually have succeeded in establishing absolute supremacy over the other states in the region".

The ancient Chinese system was relatively enclosed, whereas the European system began to expand its reach to the rest of the world from the onset of system formation... In addition, overseas provided outlet for territorial competition, thereby allowing international competition on the European continent to ... trump the ongoing pressure toward convergence.

In the 1945 book, The Precarious Balance, on four centuries of the European power struggle, Ludwig Dehio explained the durability of the European states system by its overseas expansion: "Overseas expansion and the system of states were born at the same time; the vitality that burst the bounds of the Western world also destroyed its unity." In a more famous 1945 book, Reves similarly argued that the era of outward expansion is forever closed and the historic trend of expansion will result in direct collision between the remaining powers. Edward Carr causally linked the end of the overseas outlet for imperial expansion and World Wars. In the nineteenth century, he wrote during the Second World War, imperialist wars were waged against "primitive" peoples. "It was silly for European countries to fight against one another when they could still ... maintain social cohesion by continuous expansion in Asia and Africa. Since 1900, however, this has no longer been possible: "the situation has radically changed". Now wars are between "imperial powers." Hans Morgenthau wrote that the very imperial expansion into relatively empty geographical spaces in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth centuries, in Africa, Eurasia, and western North America, deflected great power politics into the periphery of the earth, thereby reducing conflict. For example, the more attention Russia, France and the United States paid to expanding into far-flung territories in imperial fashion, the less attention they paid to one another, and the more peaceful, in a sense, the world was. But by the late nineteenth century, the consolidation of the great nation-states and empires of the West was consummated, and territorial gains could only be made at the expense of one another. John H. Herz outlined one "chief function" of the overseas expansion and the impact of its end:

[A] European balance of power could be maintained or adjusted because it was relatively easy to divert European conflicts into overseas directions and adjust them there. Thus the openness of the world contributed to the consolidation of the territorial system. The end of the 'world frontier' and the resulting closedness of an interdependent world inevitably affected the system's effectiveness.

Some later commentators drew similar conclusions:

For some commentators, the passing of the Nineteenth century seemed destined to mark the end of this long era of European empire building. The unexplored and unclaimed "blank" spaces on the world map were rapidly diminishing ... and the sense of "global closure" prompted an anxious fin-de-siècle debate about the future of the great empires ... The "closure" of the global imperial system implied ... the beginning of a new era of intensifying inter-imperial struggle along borders that now straddled the globe.

The opportunity for any system to expand in size seems almost a necessary condition for it to remain balanced, at least over the long haul. Far from being impossible or exceedingly improbable, systemic hegemony is likely under two conditions: "when the boundaries of the international system remain stable and no new major powers emerge from outside the system." With the system becoming global, further expansion is precluded. The geopolitical condition of "global closure" will remain to the end of history. Since "the contemporary international system is global, we can rule out the possibility that geographic expansion of the system will contribute to the emergence of a new balance of power, as it did so many times in the past." As Quincy Wright had put it, "this process can no longer continue without interplanetary wars."

One of leading experts on world-system theory, Christopher Chase-Dunn, noted that the circumscription theory is applicable for the global system, since the global system is circumscribed. In fact, within less than a century of its circumscribed existence the global system overcame the centuries-old balance of power and reached the unipolarity. Given "constant spatial parameters" of the global system, its unipolar structure is neither historically unusual nor theoretically surprising.

Randall Schweller theorized that a "closed international system", such as the global became a century ago, would reach "entropy" in a kind of thermodynamic law. Once the state of entropy is reached, there is no going back. The initial conditions are lost forever. Stressing the curiosity of the fact, Schweller writes that since the moment the modern world became a closed system, the process has worked in only one direction: from many poles to two poles to one pole. Thus unipolarity might represent the entropy—stable and permanent loss of variation—in the global system.

Present

Chalmers Johnson argues that the US global network of hundreds of military bases already represents a global empire in its initial form:

For a major power, prosecution of any war that is not a defense of the homeland usually requires overseas military bases for strategic reasons. After the war is over, it is tempting for the victor to retain such bases and easy to find reasons to do so. Commonly, preparedness for a possible resumption of hostilities will be invoked. Over time, if a nation's aims become imperial, the bases form the skeleton of an empire.

Simon Dalby associates the network of bases with the Roman imperial system:

Looking at these impressive facilities which reproduce substantial parts of American suburbia complete with movie theatres and restaurant chains, the parallels with Roman garrison towns built on the Rhine, or on Hadrian's wall in England, where the remains are strikingly visible on the landscape, are obvious ... Less visible is the sheer scale of the logistics to keep garrison troops in residence in the far-flung reaches of empire ... That [military] presence literally builds the cultural logic of the garrison troops into the landscape, a permanent reminder of imperial control.