The theory of consumer choice is the branch of microeconomics that relates preferences to consumption expenditures and to consumer demand curves. It analyzes how consumers maximize the desirability of their consumption (as measured by their preferences subject to limitations on their expenditures), by maximizing utility subject to a consumer budget constraint. Factors influencing consumers' evaluation of the utility of goods include: income level, cultural factors, product information and physio-psychological factors.

Consumption is separated from production, logically, because two different economic agents are involved. In the first case, consumption is determined by the individual. Their specific tastes or preferences determine the amount of utility they derive from goods and services they consume. In the second case, a producer has different motives to the consumer in that they are focussed on the profit they make. This is explained further by producer theory. The models that make up consumer theory are used to represent prospectively observable demand patterns for an individual buyer on the hypothesis of constrained optimization. Prominent variables used to explain the rate at which the good is purchased (demanded) are the price per unit of that good, prices of related goods, and wealth of the consumer.

The law of demand states that the rate of consumption falls as the price of the good rises, even when the consumer is monetarily compensated for the effect of the higher price; this is called the substitution effect. As the price of a good rises, consumers will substitute away from that good, choosing more of other alternatives. If no compensation for the price rise occurs, as is usual, then the decline in overall purchasing power due to the price rise leads, for most goods, to a further decline in the quantity demanded; this is called the income effect. As the wealth of the individual rises, demand for most products increases, shifting the demand curve higher at all possible prices.

In addition, people's judgments and decisions are often influenced by systemic biases or heuristics and are strongly dependent on the context in which the decisions are made, small or even unexpected changes in the decision-making environment can greatly affect their decisions.

The basic problem of consumer theory takes the following inputs:

- The consumption set C – the set of all bundles that the consumer could conceivably consume.

- A preference relation over the bundles of C. This preference relation can be described as an ordinal utility function, describing the utility that the consumer derives from each bundle.

- A price system, which is a function assigning a price to each bundle.

- An initial endowment, which is a bundle from C that the consumer initially holds. The consumer can sell all or some of his initial bundle in the given prices, and can buy another bundle in the given prices. He has to decide which bundle to buy, under the given prices and budget, in order to maximize their utility.

Behavioral economics

Behavioral economics has criticized neoclassical consumer choice theory because reality is more complex that what the theory can determine itself.

Firstly, consumers use heuristics, which means they do not scrutinize decisions too closely but rather make broad generalizations. Further, it is deemed not worthwhile to attempt to determine the value of specific behavior. Heuristics are techniques for simplifying the decision-making process by omitting or disregarding certain information and focusing exclusively on particular elements of alternatives. While some heuristics must be utilized purposefully and deliberately, others can be used relatively effortlessly, even without our conscious awareness. Consumption by individuals is typically impacted by advertising and consumer habits as well.

Secondly, consumers struggle to give standard utils and instead rank distinct options in order of preference, which is referred to as ordinal utility.

Thirdly, it is not always likely that a consumer would stay rational and make the choice which maximizes their utility. Sometimes, individuals are irrational. For example, a consumer making impulsive purchases is not a rational choice. The rise of the internet and social networks may cause changes in consumer behavior, resulting in more planned and sensible purchase processes.

Fourthly, individuals can be reluctant to spend cash on particular items because they have preconceived boundaries on how much they can afford to spend on 'luxuries,' according to their mental accounting.

Lastly, it is not easy to separate products in the market. Some items, such as an electronic car or a refrigerator, are only purchased occasionally and cannot be mathematically divided.

Example: homogeneous divisible goods

Consider an economy with two types of homogeneous divisible goods, traditionally called X and Y.

- The consumption set is , i.e. the set of all pairs where and . Each bundle contains a non-negative quantity of good X and a non-negative quantity of good Y.

- A typical preference relation can be represented by a set of indifference curves. Each curve represents a set of bundles that give the consumer the same utility. A typical utility function is the Cobb–Douglas function: , which is shown in the figure below.

- A typical price system assigns a price to each type of good, such that the cost of bundle is .

- A typical initial endowment for an individual is fixed income, which along with transparent prices of goods implies a budget constraint. The consumer can choose any point on or below the budget constraint line In the diagram. This line is downward sloped and linear since it represents the boundary of the inequality . In other words, the amount spent on both goods together is less than or equal to the income of the consumer.

The consumer will choose the indifference curve with the highest utility that is attainable within their budget constraint. Every point on indifference curve I3 is outside the budget constraint. As a result, the most optimal point for the individual is where the indifference curve I2 is tangent to the budget constraint. As a result, the individual will purchase of good X and of good Y.

Indifference curve analysis begins with the utility function. The utility function is treated as an index of utility. All that is necessary is that the utility index change as more preferred bundles are consumed.

The tangent point between the indifference curve and the budget line is the point at which consumer satisfaction is maximized.

Indifference curves are typically numbered with the number increasing as more preferred bundles are consumed. The numbers have no cardinal significance; for example, if three indifference curves are labeled 1, 4, and 16 respectively that means nothing more than the bundles "on" indifference curve 4 are more preferred than the bundles "on" indifference curve 1.

The income effect and price effect explain how the change in price of a good changes the consumption of the good. The theory of consumer choice examines the trade-offs and decisions people make in their role as consumers as prices and their income change.

Characteristics of the indifference curve

Indifference curves are heuristic devices used in microeconomics to convey preferences of a consumer graphically along with the limitations of a consumer's budget.

An indifference curve shows the various combination of two goods that leave the consumer equally satisfied. For example, every point on the indifference curve I1 (as shown in the figure above), which represents a unique combination of good X and good Y, will give the consumer the same utility.

Indifference curves have a few assumptions that explain their nature.

Firstly, indifference curves are typically convex to the origin of the graph. This is because it is assumed that a given consumer will sacrifice consumption in one good for more consumption of the other good. Thus, the marginal rate of substitution (MRS), which is the slope of the indifference curve at any single point along the curve, will decrease when moving down a given indifference curve. Indifference curves can also take various other shapes depending on the preferences of the consumer.

Secondly, for a given consumer, their indifference curves cannot intersect each other. This is because the same set of consumption for a given individual cannot represent two different utility values.

Thirdly, it is assumed that individuals are more satisfied with a bundle of goods on an indifference curve that is further away from the origin. From the graph above, the indifference curve I3 would give the consumer the highest utility whereas I1 would give the lowest utility.

The indifference curves shown in the figure above adhere to the three assumptions outlined in that they are convex, do not intersect, and have a higher utility the further the indifference curve is away from the origin.

Example: land

As a second example, consider an economy that consists of a large land-estate L.

- The consumption set is , i.e. the set of all subsets of L (all land parcels).

- A typical preference relation can be represented by a utility function which assigns, to each land parcel, its total "fertility" (the total amount of grain that can be grown in that land).

- A typical price system assigns a price to each land parcel, based on its area.

- A typical initial endowment is either a fixed income, or an initial parcel which the consumer can sell and buy another parcel.

Sunk cost effect

According to the laws of economic logic, sunk costs and making decisions should be irrelevant. However, there is a widespread irrationality in people's actual investment activities, production and daily activities that takes sunk costs into account when making decisions.

Sunk costs for individuals may be represented by behaviour in which they make decisions based on the fact that they have paid for this good or service irrespective of current circumstances. An example of this is a consumer who has already purchased their ticket for a concert and may travel through a storm to be able to attend the concert in order to not waste their ticket.

Another example is different payment schedules for gym members may result in different levels of potential sunk costs and affect the frequency of gym visits by consumers. That is to say, the payment schedule with other less frequent (e.g., quarterly, semi-annual or annual payment schedule), compared to a month pay the fee to the gym in a larger, these factors to reduce the cost and reduce the psychological sunk costs, more vivid sunk costs significantly increased people's gym visits. In summary, the behaviour of consumers in these two examples can be characterised by their ideal that losses loom larger than gains.

Role of time constraint effect

Highly relevant to the study and understanding of consumer choice is the role of time contraint effects. This effect is related to the available time consumers have before making their decision on whether to buy a product or service and which product or service to buy. With the incessant exposure consumers have to businesses through the avenues of social media, television, billboards and radio, time constraint effects can significantly impact the decision-making process of these consumers.

A study was conducted to measure the computational processes of subjects when faced with a decision to choose a product from a bundle of slightly differentiated products, whilst faced with a time constraint. The study was conducted through an experiment in which participants were in a supermarket-like environment and were asked to pick a snack food item from a screenshot out of a set of either 4, 9 or 16 similar items with a 3-second time window.

The results show that consumers are typically good at optimizing items that they have seen within the search process, i.e., they can easily make a choice from the "seen-set" of items. The results also show that consumers mostly use the hybrid model as a computational process for consumer choice. The data is most qualitatively consistent with the hybrid model rather than the optimal or satisfying models.

This reliance on impulsive data however isn't necessarily representative of today's market, throughout the pandemic consumers where largely forced to use online shopping methods making browsing between competitors easier, allowing for indulgence in research and conversations outside of the retailers control and evaluation of the need for a product to be completed at the individuals pace. This indicates that the time constraint effect may be less controlling of consumers choice than initially discussed.

However, important consideration should be made based temporal effects of a purchase. A study found that consumers often fall into a prevention-promotion mindset depending on the urgency of a decision. A prevention mindset comes from the need for your goals to align with your responsibilities. A promotion mindset revolves around the experience of new things. When faced with a purchase consumers were found to adopt the prevention mindset however when the purchase was distant a promotion mindset was adopted.

In conclusion the role of the time constraint effect on consumer choice is highly relevant when informing consumer choices. With the ability to extend the time constraint by using remote shopping consumers can often make a more informed decision however when the time for purchase arrives consumers often fall into a prevention focus mindset.

Effect of online reviews

During the online shopping process, retailers encourage customers to share their product reviews on digital platforms such as e-commerce websites and social media, which in turn helps other shoppers to have a better understanding of the product. Online consumer reviews play a crucial role in providing product information before consumers make a purchase decision. These reviews, full of desires, preferences and behavioural insights, are a valuable source of data for both consumers and businesses. By understanding consumer behaviour and preferences, businesses can develop strategic plans to improve the quality of their services and tailor their offerings to better meet the needs of their customers.

For example, when consumers do an online search for hotels, they can compare prices, locations, services and other aspects of various potential hotels on the site. The platform can also provide personalised recommendations based on a user's search history and preferences. Based on the attributes listed for each hotel, consumers can make an informed decision that is influenced by the consistency between their perceived hotel performance and their preferences – a classic multi-attribute decision making (MADM) problem. Vocabulary-based sentiment analysis is incorporated into online reviews to create product rankings that take into account the sentiment score of the review, the brand ranking of the product and the usefulness of the review.

In the context of travel, travellers' choices and behaviours when selecting restaurants are heavily influenced by their travel classification or purpose, such as leisure, business or adventure. The study's modelling results suggest that travellers show diverse preferences in terms of dining behaviour, depending on factors such as environment, type of cuisine, price range and dietary restrictions. While the study provides valuable insights into restaurant decision-making, it also acknowledges limitations and suggests other directions for research to further explore consumer preferences in various contexts.

However, the sheer volume of online reviews and the need to consider various attributes when making decisions can be overwhelming for consumers. In many cases, it can be a challenge to discern genuine reviews from fake ones or marketing-driven content. Therefore, tools and methods must be developed to help consumers make informed choices by helping them rank product candidates based on other consumers' reviews and their preferences. The use of artificial intelligence and machine learning algorithms has the potential to help sift through large amounts of data, extract useful insights and provide personalised recommendations to consumers.

In short, online consumer reviews are an important resource for shoppers and businesses alike. Using this information can help businesses better understand consumer preferences, improve their offerings and ultimately increase customer satisfaction. For consumers, having access to aggregated, relevant and trustworthy information can greatly enhance their decision-making process and overall online shopping experience.

Effect of a price change

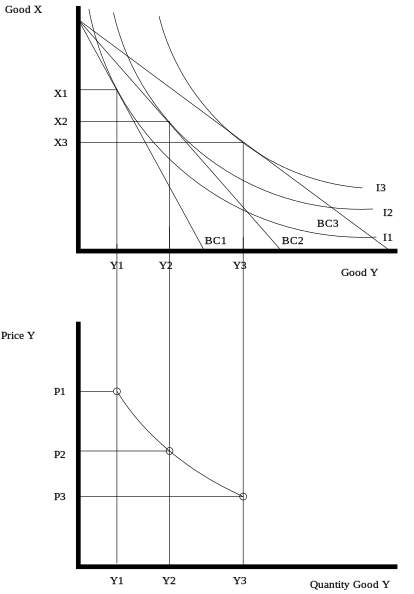

The indifference curves and budget constraint can be used to predict the effect of changes to the budget constraint. The graph below shows the effect of a price increase for good Y. If the price of Y increases, the budget constraint will pivot from to . Notice that because the price of X does not change, the consumer can still buy the same amount of X if he or she chooses to buy only good X. On the other hand, if the consumer chooses to buy only good Y, he or she will be able to buy less of good Y because its price has increased.

Now, the consumption of good X and Y will be re-allocated to account for the price change in good Y. To maximize their utility, the consumption bundle that is on the highest indifference curve that is tangent to . This consumption bundle is now (X1, Y1) as shown in the figure below. As a result, the amount of good Y bought has shifted from Y2 to Y1, and the amount of good X bought has shifted from X2 to X1. The opposite effect will occur if the price of Y decreases causing the budget constrain to shift from to , and the highest indifference curve that maximises the consumers utility shifts from I2 to I3.

If these curves are plotted for many different prices of good Y, a demand curve for good Y can be constructed. The diagram below shows the demand curve for good Y as its price varies. Alternatively, if the price for good Y is fixed and the price for good X is varied, a demand curve for good X can be constructed.

Income effect

The income effect is the phenomenon observed through changes in purchasing power. It reveals the change in quantity demanded brought by a change in real income. Graphically, as long as the prices remain constant, changing income will create a parallel shift of the budget constraint. Increasing income will shift the budget constraint right since more of both goods can be bought by the consumer. On the other hand, a decrease in income will shift the budget constraint to the left.

Depending on the indifference curves, as income increases, the quantity purchased of a good can either increase, decrease or stay the same. In the figure below, good Y is a normal good since the amount purchased increased as the budget constraint shifted from BC1 to the higher income budget constraint, BC2. However, good X is an inferior good since the quantity purchased by the consumer decreased as their income increased.

is the change in the demand for good 1 when we change income from to , holding the price of good 1 fixed at :

The equilibrium points at various levels of consumer's income builds the income consumption curve. This curve traces out the income consumption curve traces out the income effect on the quantity consumed of the goods.

Price effect as the sum of substitution and income effects

Every price change can be decomposed into an income effect and a substitution effect; the price effect is the sum of substitution and income effects.

The substitution effect is the change in demands resulting from a price change that alters the slope of the budget constraint but leaves the consumer on the same indifference curve. In other words, it illustrates the consumer's new consumption basket after the price change while being compensated as to allow the consumer to be as satisfied as he or she was previously. By this effect, the consumer is posited to substitute toward the good that becomes comparatively less expensive. In the illustration below this corresponds to an imaginary budget constraint denoted SC being tangent to the indifference curve I1. Then the income effect from the rise in purchasing power from a price fall reinforces the substitution effect. If the good is an inferior good, then the income effect will offset in some degree the substitution effect. If the income effect for an inferior good is sufficiently strong, the consumer will buy less of the good when it becomes less expensive. This is also known as a Giffen good (commonly believed to be a rarity).

The substitution effect, , is the change in the amount demanded for when the price of good falls from to (represented by the budget constraint shifting from to and thus increasing purchasing power) and, at the same time, the money income falls from to to keep the consumer at the same level of utility on I1:

The substitution effect increases the amount demanded of good from to in the diagram. In the example shown, the income effect of the fall in partly offsets the substitution effect as the amount demanded of in the absence of an offsetting income change ends up at thus the income effect from the rise in purchasing power due to the price drop is that the quantity demanded of goes from to . The total effect of the price drop of good Y on the quantity demanded is the sum of the substitution effect and the income effect.

Indifference curves for goods that are perfect substitutes or complements

Perfect substitutes

A perfect substitute is a good or service which can be used in exactly the same way as the good or service it replaces. Products which are perfect substitutes for one another will exhibit straight lines on the indifference curve (as shown in the figure to the right). This demonstrates that the relative utility of one good is equivalent to the relative utility of the other, regardless of their quantity. An example of perfect substitutes could be Coca-Cola compared to Pepsi Max. A consumer who considers these products as perfect substitutes will be indifferent to spending all of their budget on strictly one or the other.

Perfect complements

A perfect complement is a good or service whose appeal increases with the popularity of its complement. The relationship between both goods X and Y are naturally dependent on each other along with the concept of consumption being dependent upon other consumption. Products that are perfect complements will be demonstrated graphically on an indifference curve with two lines at perfect right angles to one another (as shown in the figure to the right). This demonstrates that the demand and consumption of one good is inherently tied to the other. In other words, when the consumption of one good increases, as does the consumption of the complementary good. An example of complementary goods is shown in the figure to the right. Left shoes and right shoes can be considered perfect complements as the ratio between sales of left and right shoes will never shift noticeably from 1:1.

Utility

The usefulness of a good is a key factor when discussing consumer decision making. When a product both meets the needs of a consumer and has value it has utility. Utility can be quantified through a set of numerical values that reflect the relative rankings of various bundles of goods measured by consumers preference in their consumption.

Utility function measures the preferences consumers apply to their consumption of goods and services. One of the most well known utility functions is the Cobb–Douglas utility function.

Marginal utility

Marginal utility differs from utility as it refers to the additional benefit derived from consuming one more unit of a specific good or service. Marginal utility result can be positive, neutral or negative depending on the outcomes for the consumer. Utility is not constant, and for every additional unit consumed, often the consumer experiences what economists refer to as the diminishing marginal utility or diminishing returns, where each additional unit adds less and less marginal utility.

It can be represented by the formula below:

- MUZ = △U/△Z

where MUZ represents the marginal utility of good Z; △U and △Z represent changes in utility and consumption of good Z respectively.

Assumptions

The behavioral assumption of the consumer theory proposed herein is that all consumers seek to maximize utility. Traditionally in economics, this activity of maximizing utility has been deemed as the "rational" behavior of decision makers. More specifically, in the eyes of economists, all consumers seek to maximize their utility function subject to a budgetary constraint. In other words, economists assume that consumers will always choose the "best" bundle of goods they can afford. Consumer theory is therefore based on generating refutable hypotheses about the nature of consumer demand from this behavioral postulate.

In order to reason from the central postulate towards a useful model of consumer choice, it is necessary to make additional assumptions about the certain preferences that consumers employ when selecting their preferred "bundle" of goods. These are relatively strict, allowing for the model to generate more useful hypotheses with regard to consumer behavior than weaker assumptions, which would allow any empirical data to be explained in terms of stupidity, ignorance, or some other factor, and hence would not be able to generate any predictions about future demand at all. For the most part, however, they represent statements which would only be contradicted if a consumer was acting in (what was widely regarded as) a strange manner. In this vein, the modern form of consumer choice theory assumes:

- Consumer choice theory is based on the assumption that the consumer fully understands their own preferences, allowing for a simple but accurate comparison between any two bundles of good presented.[23] That is to say, it is assumed that if a consumer is presented with two consumption bundles A and B each containing different combinations of n goods, the consumer can unambiguously decide if (s)he prefers A to B, B to A, or is indifferent to both. The few scenarios where it is possible to imagine that decision-making would be very difficult are thus placed "outside the domain of economic analysis". However, discoveries in behavioral economics has found that actual decision making is affected by various factors, such as whether choices are presented together or separately through the distinction bias.

- Preferences are complete

- When a consumer is faced with a choice between two goods A and B, they must rank them so that only one of the followings is true: the consumer prefers the good A to good B, the consumer prefers good B to good A, or the consumer is indifferent between the goods.

- Either A ≥ B or B ≥ A (or both) for all (A,B).

- Preference are transitive

- This assumption dictates that if good A is preferred to good B and good B is preferred to good C then good A must be preferred to good C. This also means that if the consumer is indifferent between goods A and B and is indifferent between goods B and C she will be indifferent between goods A and C. This is the consistency assumption. This assumption eliminates the possibility of intersecting indifference curves.

- If A ≥ B and B ≥ C, then A ≥ B (for all A, B, C).

- Preferences are reflexive

- Relationships are reflexive if they can be applied when both sides of the relationship are the same. Weak preference relationships are reflexive. A bundle of goods can be said to be weakly preferred to itself, but not strictly preferred to itself. As such, a consumer would say that they consider good A to be at least as good as good B. Alternatively, the axiom can be modified to read that the consumer is indifferent with regard to A and B.

- Preferences exhibit non-satiation

- The assumption of non-satiated preferences means that more is better – all else being the same, more of a commodity is better than less of it. This is the "more is always better" assumption; that in general if a consumer is offered two almost identical bundles A and B, but where B includes more of one particular good, the consumer will choose bundle B. In other words, this theory assumes that a consumer will never be completely satisfied, as they will always be happier consuming a little bit more. Among other things this assumption precludes circular indifference curves. Non-satiation in this sense is not a necessary but a convenient assumption. It avoids unnecessary complications in the mathematical models.

- Indifference curves exhibit diminishing marginal rates of substitution

- This assumption assures that indifference curves are smooth and convex to the origin and is implicit in the last assumption.

- This assumption also set the stage for using techniques of constrained optimization. This is because the shape of the indifference curve assures that the first derivative is negative and the second is positive.

- This assumption incorporates the theory of diminishing marginal utility. This theory of diminishing marginal utility states that the added satisfaction experienced by a consumer from having one additional unit of a good or service will diminish. In other words, the marginal utility of each additional unit will decline. An example of this can be illustrated by a consumer who orders several coffees throughout the course of a day. The marginal utility experienced by the first coffee will be greater than the second. The marginal utility experienced by the second coffee will be greater than the third, and so on.

- Goods are available in all quantities

- It is assumed that a consumer may choose to purchase any quantity of a goods they desire, for example, 2.6 eggs and 4.23 loaves of bread. Whilst this makes the model less precise, it is generally acknowledged to provide a useful simplification to the calculations involved in consumer choice theory, especially since consumer demand is often examined over a considerable period of time.

Note the assumptions do not guarantee that the demand curve will be negatively sloped. A positively sloped curve is not inconsistent with the assumptions.

Use value

In Marx's critique of the political economy, any labor-product has a value and a use value, and if it is traded as a commodity in markets, it additionally has an exchange value, most often expressed as a money-price. Marx acknowledges that commodities being traded also have a general utility, implied by the fact that people want them, but he argues that this by itself tells us nothing about the specific character of the economy in which they are produced and sold.

Labor-leisure trade-off

Consumer theory is also relevant when considering the trade-off between labour and leisure, allowing us to examine the choices made based on consumers preferences and constraints. In this analysis, labour and leisure are both considered goods. Since a consumer has a finite amount of time, they must make a choice between leisure (which earns no income for consumption) and labor (which does earn income for consumption). Using this method the opportunity cost of their decisions can dictate consumers actions.

The previous model of consumer choice theory is applicable with only slight modifications. Primarily, the total amount of time that an individual has to allocate is known as their "time endowment", and is often denoted as T. Next, the amount an individual allocates to labor (L) and leisure (ℓ) is constrained by T such that:

Consumption (C), which represents the amount of goods or services a person can take, is determined as the amount of labor they choose multiplied by the amount they are paid per hour of labor (their wage, often denoted w). Thus, the amount that a person consumes is:

Such that, when a consumer chooses no leisure then and .

From this labor-leisure tradeoff model, both the substitution effect and the income effect can be used to analyse various changes caused by welfare benefits, labor taxation, or tax credits.

It is important to note that the labour-leisure tradeoff will also be impacted on consumers norms, preferences and other non-economical factors. Therefore, real world applications of this relationship should be supported by an understanding of the factors previously listed to ensure oversights for consumer behaviour are avoided.