| Marsupials Temporal range:

Possible Late Cretaceous records

| |

|---|---|

|

Marsupials are a diverse group of mammals belonging to the infraclass Marsupialia. They are natively found in Australasia, Wallacea, and the Americas. One of marsupials' unique features is their reproductive strategy: the young are born in a relatively undeveloped state and then nurtured within a pouch on their mother's abdomen.

Extant marsupials encompass many species, including kangaroos, koalas, opossums, possums, Tasmanian devils, wombats, wallabies, and bandicoots.

Marsupials constitute a clade stemming from the last common ancestor of extant Metatheria, which encompasses all mammals more closely related to marsupials than to placentals. The evolutionary split between placentals and marsupials occurred 125–160 million years ago, in the Middle Jurassic–Early Cretaceous period.

Presently, close to 70% of the 334 extant marsupial species are concentrated on the Australian continent, including mainland Australia, Tasmania, New Guinea, and nearby islands. The remaining 30% are distributed across the Americas, primarily in South America, with thirteen species in Central America and a single species, the Virginia opossum, inhabiting North America north of Mexico.

Marsupial sizes range from a few grams in the long-tailed planigale, to several tonnes in the extinct Diprotodon.

The word marsupial comes from marsupium, the technical term for the abdominal pouch. It, in turn, is borrowed from the Latin marsupium and ultimately from the ancient Greek μάρσιππος mársippos, meaning "pouch".

Anatomy

(Phascolarctos cinereus)

Marsupials have typical mammalian characteristics—e.g., mammary glands, three middle ear bones (and ears that usually have tragi, varying in hearing thresholds), true hair and bone structure. However, striking differences including anatomical features separate them from eutherians.

Most female marsupials have a front pouch, which contains multiple nursing teats. Marsupials have other common structural features. Ossified patellae are absent in most modern marsupials (with exceptions) and epipubic bones are present. Marsupials (and monotremes) also lack a gross communication (corpus callosum) between the right and left brain hemispheres.

Skull and teeth

Marsupials exhibit distinct cranial features compared to placentals. Generally, their skulls are relatively small and compact. Notably, they possess frontal holes known as foramen lacrimale situated at the front of the orbit. Marsupials have enlarged cheekbones that extend further to the rear, and their lower jaw's angular extension (processus angularis) is bent toward the center. The hard palate of marsupials contains more openings than that of placentals.

Teeth differ significantly. Most Australian marsupials outside the order Diprotodontia have a varying number of incisors between their upper and lower jaws. Early marsupials had a dental formula of 5.1.3.4/4.1.3.4 per quadrant, consisting of five (maxillary) or four (mandibular) incisors, one canine, three premolars, and four molars, totaling 50 teeth. While some taxa, like the opossum, retain this original tooth count, others have reduced numbers.

For instance, members of the Macropodidae family, including kangaroos and wallabies, have a dental formula of 3/1 – (0 or 1)/0 – 2/2 – 4/4. Many marsupials typically have between 40 and 50 teeth, more than most placentals. In marsupials, the second set of teeth only grows in at the site of the third premolar and posteriorly; all teeth anterior to this erupt initially as permanent teeth.

Torso

Few general characteristics describe their skeleton. In addition to unique details in the construction of the ankle, epipubic bones (ossa epubica) are observed projecting forward from the pubic bone of the pelvis. Since these are present in males and pouchless species, it is believed that they originally had nothing to do with reproduction, but served in the muscular approach to the movement of the hind limbs. This could be explained by an original feature of mammals, as these epipubic bones are also found in monotremes. Marsupial reproductive organs differ from placentals. For them, the reproductive tract is doubled. Females have two uteri and two vaginas, and before birth, a birth canal forms between them, the median vagina. In most species, males have a split or double penis lying in front of the scrotum, which is not homologous to the placental scrota.

A pouch is present in most species. Many marsupials have a permanent bag, while in others such as the shrew opossum the pouch develops during gestation, where the young are hidden only by skin folds or in the maternal fur. The arrangement of the pouch is variable to allow the offspring to receive maximum protection. Locomotive kangaroos have a pouch opening at the front, while many others that walk or climb on all fours open in the back. Usually, only females have a pouch, but the male water opossum has a pouch that protects his genitalia while swimming or running.

General and convergences

Marsupials have adapted to many habitats, reflected in the wide variety in their build. The largest living marsupial, the red kangaroo, grows up to 1.8 metres (5 ft 11 in) in height and 90 kilograms (200 lb) in weight. Extinct genera, such as Diprotodon, were significantly larger and heavier. The smallest marsupials are the marsupial mice, which reach only 5 centimetres (2.0 in) in body length.

Some species resemble placentals and are examples of convergent evolution. This convergence is evident in both brain evolution and behaviour. The extinct thylacine strongly resembled the placental wolf, hence one of its nicknames "Tasmanian wolf". The ability to glide evolved in both marsupials (as with sugar gliders) and some placentals (as with flying squirrels), which developed independently. Other groups such as the kangaroo, however, do not have clear placental counterparts, though they share similarities in lifestyle and ecological niches with ruminants.

Body temperature

Marsupials, along with monotremes (platypuses and echidnas), typically have lower body temperatures than similarly sized placentals (eutherians), with the averages being 35 °C (95 °F) for marsupials and 37 °C (99 °F) for placentals. Some species will bask to conserve energy.

Reproductive system

Marsupials' reproductive systems differ markedly from those of placentals. During embryonic development, a choriovitelline placenta forms in all marsupials. In bandicoots, an additional chorioallantoic placenta forms, although it lacks the chorionic villi found in eutherian placentas.

Both sexes possess a cloaca, although modified by connecting to a urogenital sac and having a separate anal region in most species. The bladder of marsupials functions as a site to concentrate urine and empties into the common urogenital sinus in both females and males.

Males

Most male marsupials, except for macropods and marsupial moles, have a bifurcated penis, separated into two columns, so that the penis has two ends corresponding to the females' two vaginas. The penis is used only during copulation, and is separate from the urinary tract. It curves forward when erect, and when not erect, it is retracted into the body in an S-shaped curve. Neither marsupials nor monotremes possess a baculum. The shape of the glans penis varies among marsupial species.

The shape of the urethral grooves of the males' genitalia is used to distinguish between Monodelphis brevicaudata, M. domestica, and M. americana. The grooves form two channels that form the ventral and dorsal folds of the erectile tissue. Several species of dasyurid marsupials can also be distinguished by their penis morphology. Marsupials' only accessory sex glands are the prostate and bulbourethral glands. Male marsupials have one to three pairs of bulbourethral glands. Ampullae of vas deferens, seminal vesicles or coagulating glands are not present. The prostate is proportionally larger in marsupials than in placentals. During the breeding season, the male tammar wallaby's prostate and bulbourethral gland enlarge. However, the weight of the testes does not vary seasonally.

Females

Female marsupials have two lateral vaginas, which lead to separate uteri, both accessed through the same orifice. A third canal, the median vagina, is used for birth. This canal can be transitory or permanent. Some marsupial species store sperm in the oviduct after mating.

Marsupials give birth very early in gestation; after birth, newborns crawl up their mothers' bodies and attach themselves to a teat, which is located on the underside of the mother, either inside a pouch called the marsupium, or externally. Mothers often lick their fur to leave a trail of scent for the newborn to follow to increase their chances of reaching the marsupium. There they remain for several weeks. Offspring eventually leave the marsupium for short periods, returning to it for warmth, protection, and nourishment.

Early development

Gestation differs between marsupials and placentals. Key aspects of the first stages of placental embryo development, such as the inner cell mass and the process of compaction, are not found in marsupials. The cleavage stages of marsupial development vary among groups and aspects of marsupial early development are not yet fully understood.

Marsupials have a short gestation period—typically between 12 and 33 days, but as low as 10 days in the case of the stripe-faced dunnart and as long as 38 days for the long-nosed potoroo. The baby (joey) is born in a fetal state, equivalent to an 8–12 week human fetus, blind, furless, and small in comparison to placental newborns: sizes range from 4-800g+. A newborn can be categorized in one of three grades of development. The least developed are found in dasyurids, intermediates are found in didelphids and peramelids, and the most developed are macropods. The newborn crawls across its mother's fur to reach the pouch, where it latches onto a teat. It does not emerge for several months, during which time it relies on its mother's milk for essential nutrients, growth factors and immunological defence. Genes expressed in the eutherian placenta needed for the later stages of fetal development are expressed in females in their mammary glands during lactation. After this period, the joey spends increasing periods out of the pouch, feeding and learning survival skills. However, it returns to the pouch to sleep, and if danger threatens, it seeks refuge in its mother's pouch.

An early birth removes a developing marsupial from its mother's body much sooner than in placentals; thus marsupials lack a complex placenta to protect the embryo from its mother's immune system. Though early birth puts the newborn at greater environmental risk, it significantly reduces the dangers associated with long pregnancies, as the fetus cannot compromise the mother in bad seasons. Marsupials are altricial animals, needing intensive care following birth (cf. precocial). Newborns lack histologically mature immune tissues and are highly reliant on their mother's immune system for immunological protection.

Newborns front limbs and facial structures are much more developed than the rest of their bodies at birth. This requirement has been argued to have limited the range of locomotor adaptations in marsupials compared to placentals. Marsupials must develop grasping forepaws early, complicating the evolutive transition from these limbs into hooves, wings, or flippers. However, several marsupials do possess atypical forelimb morphologies, such as the hooved forelimbs of the pig-footed bandicoot, suggesting that the range of forelimb specialization is not as limited as assumed.

Joeys stay in the pouch for up to a year or until the next joey arrives. Joeys are unable to regulate their body temperature and rely upon an external heat source. Until the joey is well-furred and old enough to leave the pouch, a pouch temperature of 30–32 °C (86–90 °F) must be constantly maintained.

Joeys are born with "oral shields", soft tissue that reduces the mouth opening to a round hole just large enough to accept the teat. Once inside the mouth, a bulbous swelling on the end of the teat attaches it to the offspring till it has grown large enough to let go. In species without pouches or with rudimentary pouches these are more developed than in forms with well-developed pouches, implying an increased role in ensuring that the young remain attached to the teat.

Range

In Australasia, marsupials are found in Australia, Tasmania and New Guinea; throughout the Maluku Islands, Timor and Sulawesi to the west of New Guinea, and in the Bismarck Archipelago (including the Admiralty Islands) and Solomon Islands to the east of New Guinea.

In the Americas, marsupials are found throughout South America, excluding the central/southern Andes and parts of Patagonia; and through Central America and south-central Mexico, with a single species (the Virginia opossum Didelphis virginiana) widespread in the eastern United States and along the Pacific coast.

Interaction with Europeans

Europeans' first encounter with a marsupial was the common opossum. Vicente Yáñez Pinzón, commander of the Niña on Christopher Columbus' first voyage in the late fifteenth century, collected a female opossum with young in her pouch off the South American coast. He presented them to the Spanish monarchs, though by then the young were lost and the female had died. The animal was noted for its strange pouch or "second belly".

The Portuguese first described Australasian marsupials: António Galvão, a Portuguese administrator in Ternate (1536–1540), wrote a detailed account of the northern common cuscus (Phalanger orientalis):

Some animals resemble ferrets, only a little bigger. They are called Kusus. They have a long tail with which they hang from the trees in which they live continuously, winding it once or twice around a branch. On their belly they have a pocket like an intermediate balcony; as soon as they give birth to a young one, they grow it inside there at a teat until it does not need nursing anymore. As soon as she has borne and nourished it, the mother becomes pregnant again.

In the 17th century, more accounts of marsupials emerged. A 1606 record of an animal killed on the southern coast of New Guinea, described it as "in the shape of a dog, smaller than a greyhound", with a snakelike "bare scaly tail" and hanging testicles. The meat tasted like venison, and the stomach contained ginger leaves. This description appears to closely resemble the dusky pademelon (Thylogale brunii), the earliest European record of a member of the Macropodidae.

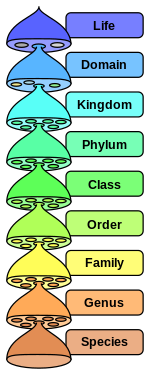

Taxonomy

Marsupials are taxonomically identified as members of mammalian infraclass Marsupialia, first described as a family under the order Pollicata by German zoologist Johann Karl Wilhelm Illiger in his 1811 work Prodromus Systematis Mammalium et Avium. However, James Rennie, author of The Natural History of Monkeys, Opossums and Lemurs (1838), pointed out that the placement of five different groups of mammals – monkeys, lemurs, tarsiers, aye-ayes and marsupials (with the exception of kangaroos, which were placed under the order Salientia) – under a single order (Pollicata) did not appear to have a strong justification. In 1816, French zoologist George Cuvier classified all marsupials under Marsupialia. In 1997, researcher J. A. W. Kirsch and others accorded infraclass rank to Marsupialia.

Classification

With seven living orders in total, Marsupialia is further divided as follows:† – Extinct

- Superorder Ameridelphia (American marsupials)

- Order Didelphimorphia (93 species) – see list of didelphimorphs

- Family Didelphidae: opossums

- Order Paucituberculata (seven species)

- Family Caenolestidae: shrew opossums

- Order Didelphimorphia (93 species) – see list of didelphimorphs

- Superorder Australidelphia (Australian marsupials)

- Order Microbiotheria (one extant species)

- Family Microbiotheriidae: monitos del monte

- Order †Yalkaparidontia (incertae sedis)

- Grandorder Agreodontia

- Order Dasyuromorphia (73 species) – see list of dasyuromorphs

- Family †Thylacinidae: thylacine

- Family Dasyuridae: antechinuses, quolls, dunnarts, Tasmanian devil, and relatives

- Family Myrmecobiidae: numbat

- Order Notoryctemorphia (two species)

- Family Notoryctidae: marsupial moles

- Order Peramelemorphia (27 species)

- Family Thylacomyidae: bilbies

- Family †Chaeropodidae: pig-footed bandicoots

- Family Peramelidae: bandicoots and allies

- Order Dasyuromorphia (73 species) – see list of dasyuromorphs

- Order Diprotodontia (136 species) – see list of diprotodonts

- Suborder Vombatiformes

- Family Vombatidae: wombats

- Family Phascolarctidae: koalas

- Family † Diprotodontidae

- Family † Palorchestidae: marsupial tapirs

- Family † Thylacoleonidae: marsupial lions

- Suborder Phalangeriformes – see list of phalangeriformes

- Family Acrobatidae: feathertail glider and feather-tailed possum

- Family Burramyidae: pygmy possums

- Family †Ektopodontidae: sprite possums

- Family Petauridae: striped possum, Leadbeater's possum, yellow-bellied glider, sugar glider, mahogany glider, squirrel glider

- Family Phalangeridae: brushtail possums and cuscuses

- Family Pseudocheiridae: ringtailed possums and relatives

- Family Tarsipedidae: honey possum

- Suborder Macropodiformes – see list of macropodiformes

- Family Macropodidae: kangaroos, wallabies, and relatives

- Family Potoroidae: potoroos, rat kangaroos, bettongs

- Family Hypsiprymnodontidae: musky rat-kangaroo

- Family † Balbaridae: basal quadrupedal kangaroos

- Suborder Vombatiformes

- Order Microbiotheria (one extant species)

Evolutionary history

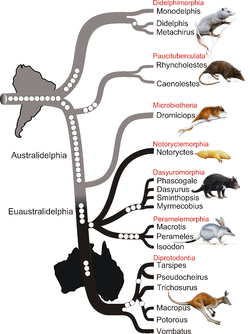

Comprising over 300 extant species, several attempts have been made to accurately interpret the phylogenetic relationships among the different marsupial orders. Studies differ on whether Didelphimorphia or Paucituberculata is the sister group to all other marsupials. Though the order Microbiotheria (which has only one species, the monito del monte) is found in South America, morphological similarities suggest it is closely related to Australian marsupials. Molecular analyses in 2010 and 2011 identified Microbiotheria as the sister group to all Australian marsupials. However, the relations among the four Australidelphid orders are not as well understood.

DNA evidence supports a South American origin for marsupials, with Australian marsupials arising from a single Gondwanan migration of marsupials from South America, across the Antarctic land bridge, to Australia. There are many small arboreal species in each group. The term "opossum" is used to refer to American species (though "possum" is a common abbreviation), while similar Australian species are properly called "possums".

The relationships among the three extant divisions of mammals (monotremes, marsupials, and placentals) were long a matter of debate among taxonomists. Most morphological evidence comparing traits such as number and arrangement of teeth and structure of the reproductive and waste elimination systems as well as most genetic and molecular evidence favors a closer evolutionary relationship between the marsupials and placentals than either has with the monotremes.

The ancestors of marsupials, part of a larger group called metatherians, probably split from those of placentals (eutherians) during the mid-Jurassic period, though no fossil evidence of metatherians themselves are known from this time. From DNA and protein analyses, the time of divergence of the two lineages has been estimated to be around 100 to 120 mya. Fossil metatherians are distinguished from eutherians by the form of their teeth; metatherians possess four pairs of molar teeth in each jaw, whereas eutherian mammals (including true placentals) never have more than three pairs. Using this criterion, the earliest known metatherian was thought to be Sinodelphys szalayi, which lived in China around 125 mya. However Sinodelphys was later reinterpreted as an early member of Eutheria. The unequivocal oldest known metatherians are now 110 million years old fossils from western North America. Metatherians were widespread in North America and Asia during the Late Cretaceous, but suffered a severe decline during the end-Cretaceous extinction event.

| Metatheria |

|

In 2022, a study provided strong evidence that the earliest known marsupial was Deltatheridium known from specimens from the Campanian age of the Late Cretaceous in Mongolia. This study placed both Deltatheridium and Pucadelphys as sister taxa to the modern large American opossums.

Marsupials spread to South America from North America during the Paleocene, possibly via the Aves Ridge. Northern Hemisphere metatherians, which were of low morphological and species diversity compared to contemporary placental mammals, eventually became extinct during the Miocene epoch.

In South America, the opossums evolved and developed a strong presence, and the Paleogene also saw the evolution of shrew opossums (Paucituberculata) alongside non-marsupial metatherian predators such as the borhyaenids and the saber-toothed Thylacosmilus. South American niches for mammalian carnivores were dominated by these marsupial and sparassodont metatherians, which seem to have competitively excluded South American placentals from evolving carnivory. While placental predators were absent, the metatherians did have to contend with avian (terror bird) and terrestrial crocodylomorph competition. Marsupials were excluded in turn from large herbivore niches in South America by the presence of native placental ungulates (now extinct) and xenarthrans (whose largest forms are also extinct). South America and Antarctica remained connected until 35 mya, as shown by the unique fossils found there. North and South America were disconnected until about three million years ago, when the Isthmus of Panama formed. This led to the Great American Interchange. Sparassodonts disappeared for unclear reasons – again, this has classically assumed as competition from carnivoran placentals, but the last sparassodonts co-existed with a few small carnivorans like procyonids and canines, and disappeared long before the arrival of macropredatory forms like felines, while didelphimorphs (opossums) invaded Central America, with the Virginia opossum reaching as far north as Canada.

Marsupials reached Australia via the Antarctic Land Bridge during the Early Eocene, around 50 mya, shortly after Australia had split off. This suggests a single dispersion event of just one species, most likely a relative to South America's monito del monte (a microbiothere, the only New World australidelphian). This progenitor may have rafted across the widening, but still narrow, gap between Australia and Antarctica. The journey must not have been easy; South American ungulate and xenarthran remains have been found in Antarctica, but these groups did not reach Australia.

In Australia, marsupials radiated into the wide variety seen today, including not only omnivorous and carnivorous forms such as were present in South America, but also into large herbivores. Modern marsupials appear to have reached the islands of New Guinea and Sulawesi relatively recently via Australia. A 2010 analysis of retroposon insertion sites in the nuclear DNA of a variety of marsupials has confirmed all living marsupials have South American ancestors. The branching sequence of marsupial orders indicated by the study puts Didelphimorphia in the most basal position, followed by Paucituberculata, then Microbiotheria, and ending with the radiation of Australian marsupials. This indicates that Australidelphia arose in South America, and reached Australia after Microbiotheria split off.

In Australia, terrestrial placentals disappeared early in the Cenozoic (their most recent known fossils being 55 million-year-old teeth resembling those of condylarths) for reasons that are not clear, allowing marsupials to dominate the Australian ecosystem. Extant native Australian terrestrial placentals (such as hopping mice) are relatively recent immigrants, arriving via island hopping from Southeast Asia.

Genetic analysis suggests a divergence date between the marsupials and the placentals at 160 million years ago. The ancestral number of chromosomes has been estimated to be 2n = 14.

A recent hypothesis suggests that South American microbiotheres resulted from a back-dispersal from eastern Gondwana. This interpretation is based on new cranial and post-cranial marsupial fossils of Djarthia murgonensis from the early Eocene Tingamarra Local Fauna in Australia that indicate this species is the most plesiomorphic ancestor, the oldest unequivocal australidelphian, and may be the ancestral morphotype of the Australian marsupial radiation.

In 2023, imaging of a partial skeleton found in Australia by paleontologists from Flinders University led to the identification of Ambulator keanei, the first long-distance walker in Australia.