Reaganomics (/reɪɡəˈnɒmɪks/; a portmanteau of Reagan and economics attributed to Paul Harvey), or Reaganism, were the neoliberal economic policies promoted by U.S. President Ronald Reagan during the 1980s. These policies are characterized as supply-side economics, trickle-down economics, or "voodoo economics" by opponents, while Reagan and his advocates preferred to call it free-market economics.

The pillars of Reagan's economic policy included increasing defense spending, balancing the federal budget and slowing the growth of government spending, reducing the federal income tax and capital gains tax, reducing government regulation, and tightening the money supply in order to reduce inflation.

The results of Reaganomics are still debated. Supporters point to the end of stagflation, stronger GDP growth, and an entrepreneurial revolution in the decades that followed. Critics point to the widening income gap, what they described as an atmosphere of greed, reduced economic mobility, and the national debt tripling in eight years which ultimately reversed the post-World War II trend of a shrinking national debt as percentage of GDP.

Historical context

Prior to the Reagan administration, the United States economy experienced a decade of high unemployment and persistently high inflation (known as stagflation). Attacks on Keynesian economic orthodoxy as well as empirical economic models such as the Phillips Curve grew. Political pressure favored stimulus resulting in an expansion of the money supply. President Richard Nixon's wage and price controls were phased out. The federal oil reserves were created to ease any future short term shocks. President Jimmy Carter had begun phasing out price controls on petroleum while he created the Department of Energy. Much of the credit for the resolution of the stagflation is given to two causes: renewed focus on increasing productivity and a three-year contraction of the money supply by the Federal Reserve Board under Paul Volcker.

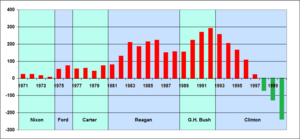

In stating that his intention was to lower taxes, Reagan's approach was a departure from his immediate predecessors. Reagan enacted lower marginal tax rates as well as simplified income tax codes and continued deregulation. During Reagan's eight year presidency, the annual deficits averaged 4.0% of GDP, compared to a 2.2% average during the preceding eight years. The real (inflation adjusted) average rate of growth in federal spending fell from 4% under Jimmy Carter to 2.5% under Ronald Reagan. GDP per employed person increased at an average 1.5% rate during the Reagan administration, compared to an average 0.6% during the preceding eight years. Private sector productivity growth, measured as real output per hour of all persons, increased at an average rate of 1.9% during Reagan's eight years, compared to an average 1.3% during the preceding eight years. Federal net outlays as a percent of GDP averaged 21.4% under Reagan, compared to 19.1% during the preceding eight years.

During the Nixon and Ford Administrations, before Reagan's election, a combined supply and demand side policy was considered unconventional by the moderate wing of the Republican Party. While running against Reagan for the Presidential nomination in 1980, George H. W. Bush had derided Reaganomics as "voodoo economics". Similarly, in 1976, Gerald Ford had severely criticized Reagan's proposal to turn back a large part of the Federal budget to the states.

Justifications

In his 1980 campaign speeches, Reagan presented his economic proposals as a return to the free enterprise principles, free market economy that had been in favor before the Great Depression and FDR's New Deal policies. At the same time he attracted a following from the supply-side economics movement, which formed in opposition to Keynesian demand-stimulus economics. This movement produced some of the strongest supporters for Reagan's policies during his term in office.

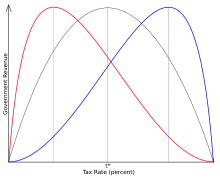

The contention of the proponents, that the tax rate cuts would more than cover any increases in federal debt, was influenced by a theoretical taxation model based on the elasticity of tax rates, known as the Laffer curve. Arthur Laffer's model predicts that excessive tax rates actually reduce potential tax revenues, by lowering the incentive to produce; the model also predicts that insufficient tax rates (rates below the optimum level for a given economy) lead directly to a reduction in tax revenues.

Ronald Reagan also cited the 14th-century Arab scholar Ibn Khaldun as an influence on his supply-side economic policies, in 1981. Reagan paraphrased Ibn Khaldun, who said that "In the beginning of the dynasty, great tax revenues were gained from small assessments," and that "at the end of the dynasty, small tax revenues were gained from large assessments." Reagan said his goal is "trying to get down to the small assessments and the great revenues."

Policies

Reagan lifted remaining domestic petroleum price and allocation controls on January 28, 1981, and lowered the oil windfall profits tax in August 1981. He ended the oil windfall profits tax in 1988. During the first year of Reagan's presidency, federal income tax rates were lowered significantly with the signing of the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981, which lowered the top marginal tax bracket from 70% to 50% and the lowest bracket from 14% to 11%. This act slashed estate taxes and trimmed taxes paid by business corporations by $150 billion over a five-year period. In 1982 Reagan agreed to a rollback of corporate tax cuts and a smaller rollback of individual income tax cuts. The 1982 tax increase undid a third of the initial tax cut. In 1983 Reagan instituted a payroll tax increase on Social Security and Medicare hospital insurance. In 1984 another bill was introduced that closed tax loopholes. According to tax historian Joseph Thorndike, the bills of 1982 and 1984 "constituted the biggest tax increase ever enacted during peacetime".

With the Tax Reform Act of 1986, Reagan and Congress sought to simplify the tax system by eliminating many deductions, reducing the highest marginal rates, and reducing the number of tax brackets. In 1983, Democrats Bill Bradley and Dick Gephardt had offered a proposal; in 1984 Reagan had the Treasury Department produce its own plan. The 1986 act aimed to be revenue-neutral: while it reduced the top marginal rate, it also cleaned up the tax base by removing certain tax write-offs, preferences, and exceptions, thus raising the effective tax on activities previously specially favored by the code.

Federal revenue share of GDP fell from 19.6% in fiscal 1981 to 17.3% in 1984, before rising back to 18.4% by fiscal year 1989. Personal income tax revenues fell during this period relative to GDP, while payroll tax revenues rose relative to GDP. Reagan's 1981 cut in the top regular tax rate on unearned income reduced the maximum capital gains rate to only 20% — its lowest level since the Hoover administration (1929 –1933). The 1986 act set tax rates on capital gains at the same level as the rates on ordinary income like salaries and wages, with both topping out at 28%.

Reagan significantly increased public expenditures, primarily the Department of Defense, which rose (in constant 2000 dollars) from $267.1 billion in 1980 (4.9% of GDP and 22.7% of public expenditure) to $393.1 billion in 1988 (5.8% of GDP and 27.3% of public expenditure); most of those years military spending was about 6% of GDP, exceeding this number in 4 different years. All these numbers had not been seen since the end of U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War in 1973. In 1981, Reagan significantly reduced the maximum tax rate, which affected the highest income earners, and lowered the top marginal tax rate from 70% to 50%; in 1986 he further reduced the rate to 28%. The federal deficit under Reagan peaked at 6% of GDP in 1983, falling to 3.2% of GDP in 1987 and to 3.1% of GDP in his final budget. The inflation-adjusted rate of growth in federal spending fell from 4% under Jimmy Carter to 2.5% under Ronald Reagan. This was the slowest rate of growth in inflation adjusted spending since Eisenhower. However, federal deficit as percent of GDP was up throughout the Reagan presidency from 2.7% at the end of (and throughout) the Carter administration. As a short-run strategy to reduce inflation and lower nominal interest rates, the U.S. borrowed both domestically and abroad to cover the Federal budget deficits, raising the national debt from $997 billion to $2.85 trillion. This led to the U.S. moving from the world's largest international creditor to the world's largest debtor nation. Reagan described the new debt as the "greatest disappointment" of his presidency.

According to William A. Niskanen, one of the architects of Reaganomics, "Reagan delivered on each of his four major policy objectives, although not to the extent that he and his supporters had hoped", and notes that the most substantial change was in the tax code, where the top marginal individual income tax rate fell from 70.1% to 28.4%, and there was a "major reversal in the tax treatment of business income", with effect of "reducing the tax bias among types of investment but increasing the average effective tax rate on new investment". Roger Porter, another architect of the program, acknowledges that the program was weakened by the many hands that changed the President's calculus, such as Congress.

Results

Overview

Spending during the years Reagan budgeted (FY 1982–89) averaged 21.6% GDP, roughly tied with President Obama for the highest among any recent President. Each faced a severe recession early in their administration. In addition, the public debt rose from 26% GDP in 1980 to 41% GDP by 1988. In dollar terms, the public debt rose from $712 billion in 1980 to $2.052 trillion in 1988, a roughly three-fold increase. The unemployment rate rose from 7% in 1980 to 11% in 1982, then declined to 5% in 1988. The inflation rate declined from 10% in 1980 to 4% in 1988.

Some economists have stated that Reagan's policies were an important part of bringing about the third longest peacetime economic expansion in U.S. history. During the Reagan administration, real GDP growth averaged 3.5%, compared to 2.9% during the preceding eight years. The annual average unemployment rate declined by 1.7 percentage points, from 7.2% in 1980 to 5.5% in 1988, after it had increased by 1.6 percentage points over the preceding eight years. Nonfarm employment increased by 16.1 million during Reagan's presidency, compared to 15.4 million during the preceding eight years, while manufacturing employment declined by 582,000 after rising 363,000 during the preceding eight years. Reagan's administration is the only one not to have raised the minimum wage. The inflation rate, 13.5% in 1980, fell to 4.1% in 1988, in part because the Federal Reserve increased interest rates (prime rate peaking at 20.5% in August 1981). The latter contributed to a recession from July 1981 to November 1982 during which unemployment rose to 9.7% and GDP fell by 1.9%. Additionally, income growth slowed for middle- and lower-class (2.4% to 1.8%) and rose for the upper-class (2.2% to 4.83%).

The misery index, defined as the inflation rate added to the unemployment rate, shrank from 19.33 when he began his administration to 9.72 when he left, the greatest improvement record for a President since Harry S. Truman left office. In terms of American households, the percentage of total households making less than $10,000 a year (in real 2007 dollars) shrank from 8.8% in 1980 to 8.3% in 1988 while the percentage of households making over $75,000 went from 20.2% to 25.7% during that period, both signs of progress.

Employment

The job growth (measured for non-farm payrolls) under the Reagan administration averaged 168,000 per month, versus 216,000 for Carter, 55,000 for H.W. Bush, and 239,000 for Clinton. The annual job growth percentages (comparing the beginning and ending number of jobs during their time in office to determine an annual growth rate) show that jobs grew by 2.0% annually under Reagan, versus 3.1% under Carter, 0.6% under H.W. Bush, and 2.4% under Clinton.

The unemployment rate averaged 7.5% under Reagan, compared to an average 6.6% during the preceding eight years. Declining steadily after December 1982, the rate was 5.4% the month Reagan left office.

The labor force participation rate increased by 2.6 percentage points during Reagan's eight years, compared to 3.9 percentage points during the preceding eight years.

Some commentators have asserted that over one million jobs were created in a single month — September 1983. Although official data support that figure, it was caused by nearly 700,000 AT&T workers going on strike and being counted as job losses in August 1983, with a quick resolution of the strike leading workers to return in September, then being counted as job gains.

Growth rates

Following the 1981 recession, the unemployment rate had averaged slightly higher (6.75% vs. 6.35%), productivity growth lower (1.38% vs. 1.92%), and private investment as a percentage of GDP slightly less (16.08% vs. 16.86%). In the 1980s, industrial productivity growth in the United States matched that of its trading partners after trailing them in the 1970s. By 1990, manufacturing's share of GNP exceeded the post-World War II low hit in 1982 and matched "the level of output achieved in the 1960s when American factories hummed at a feverish clip".

GDP growth

Real GDP grew over one-third during Reagan's presidency, an over $2 trillion increase. The compound annual growth rate of GDP was 3.6% during Reagan's eight years, compared to 2.7% during the preceding eight years. Real GDP per capita grew 2.6% under Reagan, compared to 1.9% average growth during the preceding eight years.

Real wages

The average real hourly wage for production and nonsupervisory workers continued the decline that had begun in 1973, albeit at a slower rate, and remained below the pre-Reagan level in every Reagan year. While inflation remained elevated during his presidency and likely contributed to the decline in wages over this period, Reagan's critics often argue that his neoliberal policies were responsible for this and also led to a stagnation of wages in the next few decades.

Income and wealth

In nominal terms, median household income grew at a compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 5.5% during the Reagan presidency, compared to 8.5% during the preceding five years (pre-1975 data are unavailable). Real median family income grew by $4,492 during the Reagan period, compared to a $1,270 increase during the preceding eight years. After declining from 1973 through 1980, real mean personal income rose $4,708 by 1988. Nominal household net worth increased by a CAGR of 8.4%, compared to 9.3% during the preceding eight years.

Poverty level

The percentage of the total population below the poverty level increased from 13.0% in 1980 to 15.2% in 1983, then declined back to 13.0% in 1988. During Reagan's first term, critics noted homelessness as a visible problem in U.S. urban centers. According to Don Mitchell, the increased cuts to spending on housing and social services under Reagan was a contributing factor to the homeless population nearly doubling in just three years, from 1984 to 1987. In the closing weeks of his presidency, Reagan told David Brinkley that the homeless "make it their own choice for staying out there," noting his belief that there "are shelters in virtually every city, and shelters here, and those people still prefer out there on the grates or the lawn to going into one of those shelters". He also stated that "a large proportion" of them are "mentally impaired", which he believed to be a result of lawsuits by the ACLU (and similar organizations) against mental institutions.

Federal income tax and payroll tax levels

During the Reagan administration, fiscal year federal receipts grew from $599 billion to $991 billion (an increase of 65%) while fiscal year federal outlays grew from $678 billion to $1144 billion (an increase of 69%). According to a 1996 report of the Joint Economic Committee of the United States Congress, during Reagan's two terms, and through 1993, the top 10% of taxpayers paid an increased share of income taxes (not including payroll taxes) to the Federal government, while the lowest 50% of taxpayers paid a reduced share of income tax revenue. Personal income tax revenues declined from 9.4% GDP in 1981 to 8.3% GDP in 1989, while payroll tax revenues increased from 6.0% GDP to 6.7% GDP during the same period.

Tax receipts

Both CBO and the Reagan Administration forecast that individual and business income tax revenues would be lower if the Reagan tax cut proposals were implemented, relative to a policy baseline without those cuts, by about $50 billion in 1982 and $210 billion by 1986. According to a 2003 Treasury study, the tax cuts in the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 resulted in a significant decline in revenue relative to a baseline without the cuts, approximately $111 billion (in 1992 dollars) on average during the first four years after implementation or nearly 3% GDP annually. Other tax bills had neutral or, in the case of the Tax Equity and Fiscal Responsibility Act of 1982, a (~+1% of GDP) increase in revenue as a share of GDP. The study did not examine the longer-term impact of Reagan tax policy, including sunset clauses and "the long-run, fully-phased-in effect of the tax bills". The fact that tax receipts as a percentage of GDP fell following the Economic Recovery Tax Act of 1981 shows a decrease in tax burden as share of GDP and a commensurate increase in the deficit, as spending did not fall relative to GDP. Total federal tax receipts increased in every Reagan year except 1982, at an annual average rate of 6.2% compared to 10.8% during the preceding eight years.

The effect of Reagan's 1981 tax cuts (reduced revenue relative to a baseline without the cuts) were at least partially offset by phased in Social Security payroll tax increases that had been enacted by President Jimmy Carter and the 95th Congress in 1977, and further increases by Reagan in 1983 and following years, also to counter the uses of tax shelters. An accounting indicated nominal tax receipts increased from $599 billion in 1981 to $1.032 trillion in 1990, an increase of 72% in current dollars. In 2005 dollars, the tax receipts in 1990 were $1.5 trillion, an increase of 20% above inflation.

Debt and government expenditures

Reagan was inaugurated in January 1981, making the first fiscal year (FY) he budgeted 1982 and the final budget 1989.

- During Reagan's presidency, the federal debt held by the public nearly tripled in nominal terms, from $738 billion to $2.1 trillion. This led to the U.S. moving from the world's largest international creditor to the world's largest debtor nation. Reagan described the new debt as the "greatest disappointment" of his presidency.

- The federal deficit as percentage of GDP rose from 2.5% of GDP in fiscal year 1981 to a peak of 5.7% of GDP in 1983, then fell to 2.7% GDP in 1989.

- Total federal outlays averaged of 21.8% of GDP from 1981–88, versus the 1974–1980 average of 20.1% of GDP. This was the highest of any President from Carter through Obama.

- Total federal revenues averaged 17.7% of GDP from 1981–88, versus the 1974–80 average of 17.6% of GDP.

- Federal individual income tax revenues fell from 8.7% of GDP in 1980 to a trough of 7.5% of GDP in 1984, then rose to 7.8% of GDP in 1988.

Business and market performance

Nominal after-tax corporate profits grew at a compound annual growth rate of 3.0% during Reagan's eight years, compared to 13.0% during the preceding eight years. The S&P 500 Index increased 113.3% during the 2024 trading days under Reagan, compared to 10.4% during the preceding 2024 trading days. The business sector share of GDP, measured as gross private domestic investment, declined by 0.7 percentage points under Reagan, after increasing 0.7 percentage points during the preceding eight years.

Size of federal government

The federal government's share of GDP increased 0.2 percentage points under Reagan, while it decreased 1.5 percentage points during the preceding eight years. The number of federal civilian employees increased 4.2% during Reagan's eight years, compared to 6.5% during the preceding eight years.

As a candidate, Reagan asserted he would shrink government by abolishing the Cabinet-level departments of energy and education. He abolished neither, but elevated veterans affairs from independent agency status to Cabinet-level department status.

Income distribution

Continuing a trend that began in the 1970s, income inequality grew and accelerated in the 1980s. The Economist wrote in 2006: "After the 1973 oil shocks, productivity growth suddenly slowed. A few years later, at the start of the 1980s, the gap between rich and poor began to widen." According to the CBO:

- The top 1% of income earners' share of income before transfers and taxes rose from 9.0% in 1979 to a peak of 13.8% in 1986, before falling to 12.3% in 1989.

- The top 1% share of income earners' of income after transfers and taxes rose from 7.4% in 1979 to a peak of 12.8% in 1986, before falling to 11.0% in 1989.

- The bottom 90% had a lower share of the income in 1989 vs. 1979.

Analysis

According to a 1996 study by the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank, on 8 of the 10 key economic variables examined, the American economy performed better during the Reagan years than during the pre- and post-Reagan years. The study asserted that real median family income grew by $4,000 during the eight Reagan years and experienced a loss of almost $1,500 in the post-Reagan years. Interest rates, inflation, and unemployment fell faster under Reagan than they did immediately before or after his presidency. The only economic variable that was lower during period than in both the pre- and post-Reagan years was the savings rate, which fell rapidly in the 1980s. The productivity rate was higher in the pre-Reagan years but lower in the post-Reagan years. The Cato study was dismissive of any positive effects of tightening, and subsequent loosening, of Federal Reserve monetary policy under "inflation hawk" Paul Volcker, whom President Carter had appointed in 1979 to halt the persistent inflation of the 1970s.

Economic analyst Stephen Moore stated in the Cato analysis, "No act in the last quarter century had a more profound impact on the U.S. economy of the eighties and nineties than the Reagan tax cut of 1981." He argued that Reagan's tax cuts, combined with an emphasis on federal monetary policy, deregulation, and expansion of free trade created a sustained economic expansion, the greatest American sustained wave of prosperity ever. He also claims that the American economy grew by more than a third in size, producing a $15 trillion increase in American wealth. Consumer and investor confidence soared. Cutting federal income taxes, cutting the U.S. government spending budget, cutting programs, scaling down the government work force, maintaining low interest rates, and keeping a watchful inflation hedge on the monetary supply was Ronald Reagan's formula for a successful economic turnaround.

Milton Friedman stated, "Reaganomics had four simple principles: Lower marginal tax rates, less regulation, restrained government spending, noninflationary monetary policy. Though Reagan did not achieve all of his goals, he made good progress."

The Tax Reform Act of 1986 and its impact on the alternative minimum tax (AMT) reduced nominal rates on the wealthy and eliminated tax deductions, while raising tax rates on lower-income individuals. The across the board tax system reduced marginal rates and further reduced bracket creep from inflation. The highest income earners (with incomes exceeding $1,000,000) received a tax break, restoring a flatter tax system. In 2006, the IRS's National Taxpayer Advocate's report characterized the effective rise in the AMT for individuals as a problem with the tax code. Through 2007, the revised AMT had brought in more tax revenue than the former tax code, which has made it difficult for Congress to reform.

Economist Paul Krugman argued the economic expansion during the Reagan administration was primarily the result of the business cycle and the monetary policy by Paul Volcker. Krugman argues that there was nothing unusual about the economy under Reagan because unemployment was reducing from a high peak and that it is consistent with Keynesian economics for the economy to grow as employment increases if inflation remains low. Krugman has also criticized Reaganomics from the standpoint of wealth and income inequality. He argues that the Reagan era tax cuts ended the post-World War II "Great Compression" of wealth held by the rich.

The CBO Historical Tables indicate that federal spending during Reagan's two terms (FY 1981–88) averaged 22.4% GDP, well above the 20.6% GDP average from 1971 to 2009. In addition, the public debt rose from 26.1% GDP in 1980 to 41.0% GDP by 1988. In dollar terms, the public debt rose from $712 billion in 1980 to $2,052 billion in 1988, a three-fold increase. Krugman argued in June 2012 that Reagan's policies were consistent with Keynesian stimulus theories, pointing to the significant increase in per-capita spending under Reagan.

William Niskanen noted that during the Reagan years, privately held federal debt increased from 22% to 38% of GDP, despite a long peacetime expansion. Second, the savings and loan problem led to an additional debt of about $125 billion. Third, greater enforcement of U.S. trade laws increased the share of U.S. imports subjected to trade restrictions from 12% in 1980 to 23% in 1988.

Economists Raghuram Rajan and Luigi Zingales pointed out that many deregulation efforts had either taken place or had begun before Reagan (note the deregulation of airlines and trucking under Carter, and the beginning of deregulatory reform in railroads, telephones, natural gas, and banking). They stated, "The move toward markets preceded the leader [Reagan] who is seen as one of their saviors." Economists Paul Joskow and Roger Noll made a similar contention.

Economist William A. Niskanen, a member of Reagan's Council of Economic Advisers wrote that deregulation had the "lowest priority" of the items on the Reagan agenda given that Reagan "failed to sustain the momentum for deregulation initiated in the 1970s" and that he "added more trade barriers than any administration since Hoover." By contrast, economist Milton Friedman has pointed to the number of pages added to the Federal Register each year as evidence of Reagan's anti-regulation presidency (the Register records the rules and regulations that federal agencies issue per year). The number of pages added to the Register each year declined sharply at the start of the Ronald Reagan presidency breaking a steady and sharp increase since 1960. The increase in the number of pages added per year resumed an upward, though less steep, trend after Reagan left office. In contrast, the number of pages being added each year increased under Ford, Carter, George H. W. Bush, Clinton, George W. Bush, and Obama. The number of pages in Federal Register is however criticized as an extremely crude measure of regulatory activity, because it can be easily manipulated (e.g. font sizes have been changed to keep page count low). The apparent contradiction between Niskanen's statements and Friedman's data may be resolved by seeing Niskanen as referring to statutory deregulation (laws passed by Congress) and Friedman to administrative deregulation (rules and regulations implemented by federal agencies). A 2016 study by the Congressional Research Service found that Reagan's average annual number of final federal regulatory rules published in the Federal Register was higher than during the Clinton, George W. Bush or Obama's administrations, even though the Reagan economy was considerably smaller than during those later presidents. Another study by the QuantGov project of the libertarian Mercatus Center found that the Reagan administration added restrictive regulations — containing such terms as "shall," "prohibited" or "may not" — at a faster average annual rate than did Clinton, Bush or Obama.

Greg Mankiw, a conservative Republican economist who served as chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers under President George W. Bush, wrote in 2007:

I used the phrase "charlatans and cranks" in the first edition of my principles textbook to describe some of the economic advisers to Ronald Reagan, who told him that broad-based income tax cuts would have such large supply-side effects that the tax cuts would raise tax revenue. I did not find such a claim credible, based on the available evidence. I never have, and I still don't ... My other work has remained consistent with this view. In a paper on dynamic scoring, written while I was working at the White House, Matthew Weinzierl and I estimated that a broad-based income tax cut (applying to both capital and labor income) would recoup only about a quarter of the lost revenue through supply-side growth effects. For a cut in capital income taxes, the feedback is larger — about 50 percent — but still well under 100 percent. A chapter on dynamic scoring in the 2004 Economic Report of the President says about the same thing.

Glenn Hubbard, who preceded Mankiw as Bush's CEA chair, also disputed the assertion that tax cuts increase tax revenues, writing in his 2003 Economic Report of the President: "Although the economy grows in response to tax reductions (because of higher consumption in the short run and improved incentives in the long run), it is unlikely to grow so much that lost tax revenue is completely recovered by the higher level of economic activity."

In 1986, Martin Feldstein — a self-described "traditional supply sider" who served as Reagan's chairman of the Council of Economic Advisers from 1982 to 1984 — characterized the "new supply siders" who emerged circa 1980:

What distinguished the new supply siders from the traditional supply siders as the 1980s began was not the policies they advocated but the claims that they made for those policies ... The "new" supply siders were much more extravagant in their claims. They projected rapid growth, dramatic increases in tax revenue, a sharp rise in saving, and a relatively painless reduction in inflation. The height of supply side hyperbole was the "Laffer curve" proposition that the tax cut would actually increase tax revenue because it would unleash an enormously depressed supply of effort. Another remarkable proposition was the claim that even if the tax cuts did lead to an increased budget deficit, that would not reduce the funds available for investment in plant and equipment because tax changes would raise the saving rate by enough to finance the increased deficit ... Nevertheless, I have no doubt that the loose talk of the supply side extremists gave fundamentally good policies a bad name and led to quantitative mistakes that not only contributed to subsequent budget deficits but that also made it more difficult to modify policy when those deficits became apparent.