From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

| Energy development | |||||||||||||||||||||

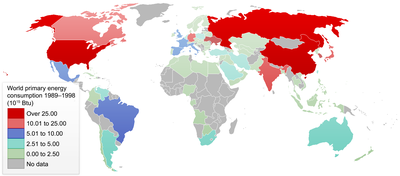

World total primary energy production

US Energy Use/Flow in 2011

Energy flow charts show the relative size of primary energy resources and end uses in the United States, with fuels compared on a common energy unit basis (2011: 97.3 quads).[3]

|

|||||||||||||||||||||

Contemporary industrial societies use primary and secondary energy sources for transportation and the production of many manufactured goods. Also, large industrial populations have various generation and delivery services for energy distribution and end-user utilization.[note 4] This energy is used by people who can afford the cost to live under various climatic conditions through the use of heating, ventilation, and/or air conditioning. Level of use of external energy sources differs across societies, along with the convenience, levels of traffic congestion, pollution sources[13] and availability of domestic energy sources.

Thousands of people in society are employed in the energy industry, of which subjectively influence and impact behaviors. The conventional industry comprises the petroleum industry[note 5] the gas industry,[note 6] the electrical power industry[note 7] the coal industry, and the nuclear power industry. New energy industries include the renewable energy industry, comprising alternative and sustainable manufacture, distribution, and sale of alternative fuels. While there is the development of new hydrocarbon sources,[14] including deepwater/horizontal drilling and fracking, are contentiously underway, commitments to mitigate climate change are driving efforts to develop sources of alternative and renewable energy.

Types of energy

Colloquially, and in non-scientific literature, the terms power,[note 8] fuels, and energy can be used as synonyms, but in the field of energy technology they possess different distinct meanings that are associated with them. An energy source is usually in the form of a closed system, the element that provides the energy by conversion from another energy form; However, the energy can be quantitative, the balance sheet is capable of containing open system energy transfers.[note 9]

Illustrative of this can be the emanations from the sun, which with its nuclear fusion is the most important energy source for the Earth[note 10] and which provides its energy in the form of radiation.

The natural elements[note 11] of the material world exist in forms that can be converted into usable energy and are resources from which society can obtain energy to produce heat, light, and motion (among the many uses). According to their nature, the power plants can be classified into:

- Primary : They are found in nature: wind, water, solar,[note 12] wood, coal, oil, nuclear.

- Secondary : Are those obtained from primary energy sources: electricity, gas.

- renewable: When the energy source used is freely regenerated in a short period and there are practically limitless reserves; An example is the solar energy that is the source of energy from the sun, or the wind[note 13] used as an energy resource. Renewable energies are:

- original solar

- natural wind (atmospheric flows)

- natural geothermal

- oceanic tidal

- natural waterfall (hydraulic flows)

- natural plant: paper, wood

- natural animal: wax, grease,[note 14] pack animals and sources of mechanical energy[note 15]

- nonrenewable: They are coming from energy limited sources on Earth in quantity and, therefore, are exhaustible. The non-renewable energy sources include, non-exclusively:

The principle stated by Antoine Lavoisier on the conservation of matter applies to energy development:[note 17] "nothing is created." Thus any energy "production" is actually a recovery transformation of the forms of energy whose origin is that of the universe.

For example, a bicycle dynamo turns in part from the kinetic energy (speed energy) of the movement of the cyclist and converting it into electrical energy will transfer in particular to its lights producing light, that is to say light energy, via the heating of the filament of the bulb and therefore heat (thermal energy). But the kinetic energy of the rider is itself biochemical energy (the ATP muscle cells) derived from the chemical energy of sugars synthesized by plants who use light energy from the sun, which runs from the nuclear energy produced by fusion of atoms of hydrogen, the material itself constitute a form of energy, called "mass energy".

Fossil fuels

The Moss Landing Power Plant in California is a fossil-fuel power station that burns natural gas in a turbine to produce electricity.

Fossil energy is from recovered fossils (like brown coal, hard coal, peat, natural gas and crude oil) and are originated in degradated products of dead plants and animals. These fossil fuels are based on the carbon cycle and thus allow stored (historic solar) energy to be recycled today. In 2005, 81% were of the world's energy needs met from fossil sources.[15] Biomass is also derived from wood and other organic wastes and modern remains. The technical development of fossil fuels in the 18th and 19th Century set the stage for the Industrial Revolution.

Fossil fuels make up the bulk of the world's current primary energy sources. The technology and infrastructure already exist for the use of fossil fuels. Petroleum energy density in terms of volume (cubic space) and mass (weight) ranks currently above that of alternative energy sources (or energy storage devices, like a battery). Fossil fuels are currently economical, and suitable for decentralized energy use.

Dependence on fossil fuels from regions or countries creates energy security risks for dependent countries.[16][17][18][19][20] Oil dependence in particular has led to war,[21] funding of radicals,[22] monopolization,[23] and socio-political instability.[24] Fossil fuels are non-renewable, un-sustainable resources, which will eventually decline in production[25] and become exhausted, with consequences to societies that remain dependent on them. Fossil fuels are actually slowly forming continuously, but are being consumed quicker than are formed.[note 18] Extracting fuels becomes increasingly extreme as society consumes the most accessible fuel deposits. Extraction in fuel mines get intensive and oil rigs drill deeper (going further out to sea).[26] Extraction of fossil fuels results in environmental degradation, such as the strip mining and mountaintop removal of coal.

Fuel efficiency is a form of thermal efficiency, meaning the efficiency of a process that converts chemical potential energy contained in a carrier fuel into kinetic energy or work. The fuel economy is the energy efficiency of a particular vehicle, is given as a ratio of distance travelled per unit of fuel consumed. Weight-specific efficiency (efficiency per unit weight) may be stated for freight, and passenger-specific efficiency (vehicle efficiency per passenger). The inefficient atmospheric combustion (burning) of fossil fuels in vehicles, buildings, and power plants contributes to urban heat islands.[27]

Conventional production of oil has peaked, conservatively, between 2007 to 2010.[note 19] In 2010, it was estimated that an investment in non-renewable resources of $8 trillion would be required to maintain current levels of production for 25 years.[28] In 2010, governments subsidized fossil fuels by an estimated $500 billion a year.[29] Fossil fuels are also a source of greenhouse gas emissions, leading to concerns about global warming if consumption is not reduced.

The combustion of fossil fuels leads to the release of pollution into the atmosphere. The fossil fuels are mainly based on organic carbon compounds. They are according to the IPCC the causes of the global warming.[30] During the combustion with oxygen in the form of heat energy, carbon dioxide released. Depending on the composition and purity of the fossil fuel also results in other chemical compounds such as nitrogen oxides (NOx) and soot and other fine particulates alternativey. Greenhouse gas emissions result from fossil fuel-based electricity generation. A typical coal plant generates billions of kilowatt hours per year.[31][note 20] Emissions from such fossil fuel power station include carbon dioxide, sulfur dioxide, small particulates, nitrogen oxides, smog with high levels of ozone, carbon monoxide (CO), hydrocarbons, volatile organic compounds (VOC), mercury, arsenic, lead, cadmium, other heavy metals, and traces of uranium.[32][33]

Nuclear

Fission

The Susquehanna Steam Electric Station, a boiling water reactor. The reactors are located inside the rectangular containment buildings towards the front of the cooling towers. The power station produces 63 million kilowatt hours per day.

American nuclear powered ships,(top to bottom) cruisers USS Bainbridge, the USS Long Beach and the USS Enterprise, the longest ever naval vessel, and the first nuclear-powered aircraft carrier. Picture taken in 1964 during a record setting voyage of 26,540 nmi (49,190 km) around the world in 65 days without refueling. Crew members are spelling out Einstein's mass-energy equivalence formula E = mc2 on the flight deck.

The Russian nuclear-powered icebreaker NS Yamal on a joint scientific expedition with the NSF in 1994

There is an ongoing debate about nuclear power.[43][44][45] Proponents, such as the World Nuclear Association, the IAEA and Environmentalists for Nuclear Energy contend that nuclear power is a safe, sustainable energy source that reduces carbon emissions.[46] Opponents, such as Greenpeace International and NIRS, contend that nuclear power poses many threats to people and the environment.[47][48][49]

Nuclear power plant accidents include the Chernobyl disaster (1986), Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster (2011), and the Three Mile Island accident (1979).[50] There have also been some nuclear submarine accidents.[50][51][52] In terms of lives lost per unit of energy generated, analysis has determined that nuclear power has caused less fatalities per unit of energy generated than the other major sources of energy generation. Energy production from coal, petroleum, natural gas and hydropower has caused a greater number of fatalities per unit of energy generated due to air pollution and energy accident effects.[53][54][55][56][57] However, the economic costs of nuclear power accidents is high, and meltdowns can take decades to clean up. The human costs of evacuations of affected populations and lost livelihoods is also significant.[58][59]

Along with other sustainable energy sources, nuclear power is a low carbon power generation method of producing electricity, with an analysis of the literature on its total life cycle emission intensity finding that it is similar to other renewable sources in a comparison of greenhouse gas(GHG) emissions per unit of energy generated.[60] With this translating into, from the beginning of nuclear power station commercialization in the 1970s, having prevented the emission of approximately 64 gigatonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent(GtCO2-eq) greenhouse gases, gases that would have otherwise resulted from the burning of fossil fuels in thermal power stations.[61]

As of 2012, according to the IAEA, worldwide there were 68 civil nuclear power reactors under construction in 15 countries,[36] approximately 28 of which in the Peoples Republic of China (PRC), with the most recent nuclear power reactor, as of May 2013, to be connected to the electrical grid, occurring on February 17, 2013 in Hongyanhe Nuclear Power Plant in the PRC.[62] In the USA, two new Generation III reactors are under construction at Vogtle. U.S. nuclear industry officials expect five new reactors to enter service by 2020, all at existing plants.[63] In 2013, four aging, uncompetitive, reactors were permanently closed.[64][65]

Japan's 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear accident, which occurred in a reactor design from the 1960s, prompted a rethink of nuclear safety and nuclear energy policy in many countries.[66] Germany decided to close all its reactors by 2022, and Italy has banned nuclear power.[66] Following Fukushima, in 2011 the International Energy Agency halved its estimate of additional nuclear generating capacity to be built by 2035.[67][68]

Fission economics

The economics of new nuclear power plants is a controversial subject, since there are diverging views on this topic, and multi-billion dollar investments ride on the choice of an energy source. Nuclear power plants typically have high capital costs for building the plant, but low direct fuel costs.In recent years there has been a slowdown of electricity demand growth and financing has become more difficult, which has an impact on large projects such as nuclear reactors, with very large upfront costs and long project cycles which carry a large variety of risks.[69] In Eastern Europe, a number of long-established projects are struggling to find finance, notably Belene in Bulgaria and the additional reactors at Cernavoda in Romania, and some potential backers have pulled out.[69] Where cheap gas is available and its future supply relatively secure, this also poses a major problem for nuclear projects.[69]

Analysis of the economics of nuclear power must take into account who bears the risks of future uncertainties. To date all operating nuclear power plants were developed by state-owned or regulated utility monopolies[70][71] where many of the risks associated with construction costs, operating performance, fuel price, and other factors were borne by consumers rather than suppliers. Many countries have now liberalized the electricity market where these risks, and the risk of cheaper competitors emerging before capital costs are recovered, are borne by plant suppliers and operators rather than consumers, which leads to a significantly different evaluation of the economics of new nuclear power plants.[72]

Two of the four EPRs under construction (in Finland and France) are significantly behind schedule and substantially over cost.[73] Following the 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, costs are likely to go up for currently operating and new nuclear power plants, due to increased requirements for on-site spent fuel management and elevated design basis threats.[74]

Nuclear power debate

The 2011 Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, the second worst nuclear incident, displaced 50,000 households after radioactive material leaked into the air, soil and sea.[75] Radiation checks led to bans on some shipments of vegetables and fish.[76]

Proponents of nuclear energy argue that nuclear power is a sustainable energy source which reduces carbon emissions and can increase energy security if its use supplants a dependence on imported fuels.[84] Proponents advance the notion that nuclear power produces virtually no air pollution, in contrast to the chief viable alternative of fossil fuel. Proponents also believe that nuclear power is the only viable course to achieve energy independence for most Western countries. They emphasize that the risks of storing waste are small and can be further reduced by using the latest technology in newer reactors, and the operational safety record in the Western world is excellent when compared to the other major kinds of power plants.[85]

Opponents say that nuclear power poses numerous threats to people and the environment and point to studies in the literature that question if it will ever be a sustainable energy source.[86] These threats include health risks and environmental damage from uranium mining, processing and transport, the risk of nuclear weapons proliferation or sabotage, and the unsolved problem of radioactive nuclear waste.[87][88][89] They also contend that reactors themselves are enormously complex machines where many things can and do go wrong, and there have been many serious nuclear accidents.[90][91] Critics do not believe that these risks can be reduced through new technology.[92] They argue that when all the energy-intensive stages of the nuclear fuel chain are considered, from uranium mining to nuclear decommissioning, nuclear power is not a low-carbon electricity source.[93][94][95]

Renewable sources

Renewable energy is generally defined as energy that comes from resources which are naturally replenished on a human timescale such as sunlight, wind, rain, tides, waves and geothermal heat.[97] Renewable energy replaces conventional fuels in four distinct areas: electricity generation, hot water/space heating, motor fuels, and rural (off-grid) energy services.[98]About 16% of global final energy consumption presently comes from renewable resources, with 10% [99] of all energy from traditional biomass, mainly used for heating, and 3.4% from hydroelectricity. New renewables (small hydro, modern biomass, wind, solar, geothermal, and biofuels) account for another 3% and are growing rapidly.[100] At the national level, at least 30 nations around the world already have renewable energy contributing more than 20% of energy supply. National renewable energy markets are projected to continue to grow strongly in the coming decade and beyond.[101] Wind power, for example, is growing at the rate of 30% annually, with a worldwide installed capacity of 282,482 megawatts (MW) at the end of 2012.

Renewable energy resources exist over wide geographical areas, in contrast to other energy sources, which are concentrated in a limited number of countries. Rapid deployment of renewable energy and energy efficiency is resulting in significant energy security, climate change mitigation, and economic benefits.[102] In international public opinion surveys there is strong support for promoting renewable sources such as solar power and wind power.[103]

While many renewable energy projects are large-scale, renewable technologies are also suited to rural and remote areas and developing countries, where energy is often crucial in human development.[104] United Nations' Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon has said that renewable energy has the ability to lift the poorest nations to new levels of prosperity.[105]

Hydroelectricity

Hydropower is produced in 150 countries, with the Asia-Pacific region generating 32 percent of global hydropower in 2010. China is the largest hydroelectricity producer, with 721 terawatt-hours of production in 2010, representing around 17 percent of domestic electricity use. There are now three hydroelectricity plants larger than 10 GW: the Three Gorges Dam in China, Itaipu Dam across the Brazil/Paraguay border, and Guri Dam in Venezuela.[106]

The cost of hydroelectricity is relatively low, making it a competitive source of renewable electricity. The average cost of electricity from a hydro plant larger than 10 megawatts is 3 to 5 U.S. cents per kilowatt-hour.[106] Hydro is also a flexible source of electricity since plants can be ramped up and down very quickly to adapt to changing energy demands. However, damming interrupts the flow of rivers and can harm local ecosystems, and building large dams and reservoirs often involves displacing people and wildlife.[106] Once a hydroelectric complex is constructed, the project produces no direct waste, and has a considerably lower output level of the greenhouse gas carbon dioxide (CO

2) than fossil fuel powered energy plants.[107]

Wind

Wind power is widely used in Europe, Asia, and the United States.[111] Several countries have achieved relatively high levels of wind power penetration, such as 21% of stationary electricity production in Denmark,[112] 18% in Portugal,[112] 16% in Spain,[112] 14% in Ireland,[113] and 9% in Germany in 2010.[112][114] By 2011, at times over 50% of electricity in Germany and Spain came from wind and solar power.[115][116] As of 2011, 83 countries around the world are using wind power on a commercial basis.[114]

Many of the world's largest onshore wind farms are located in the United States, China, and India. Most of the world's largest offshore wind farms are located in Denmark, Germany and the United Kingdom. The two largest offshore wind farm are currently the 630 MW London Array and Gwynt y Môr.

| Wind farm | Current capacity (MW) |

Country | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Alta (Oak Creek-Mojave) | 1,320 | [117] | |

| Jaisalmer Wind Park | 1,064 | [118] | |

| Capricorn Ridge Wind Farm | 662.5 | [119][120] | |

| Fântânele-Cogealac Wind Farm | 600 | [121] | |

| Fowler Ridge Wind Farm | 599.8 | [122] | |

| Horse Hollow Wind Energy Center | 735.5 | [119][120] | |

| Roscoe Wind Farm | 781.5 | [123] |

Solar[edit]

Solar technologies are broadly characterized as either passive solar or active solar depending on the way they capture, convert and distribute solar energy. Active solar techniques include the use of photovoltaic panels and solar thermal collectors to harness the energy. Passive solar techniques include orienting a building to the Sun, selecting materials with favorable thermal mass or light dispersing properties, and designing spaces that naturally circulate air.

In 2011, the International Energy Agency said that "the development of affordable, inexhaustible and clean solar energy technologies will have huge longer-term benefits. It will increase countries’ energy security through reliance on an indigenous, inexhaustible and mostly import-independent resource, enhance sustainability, reduce pollution, lower the costs of mitigating climate change, and keep fossil fuel prices lower than otherwise. These advantages are global. Hence the additional costs of the incentives for early deployment should be considered learning investments; they must be wisely spent and need to be widely shared".[124]

Photovoltaics (PV) is a method of generating electrical power by converting solar radiation into direct current electricity using semiconductors that exhibit the photovoltaic effect. Photovoltaic power generation employs solar panels composed of a number of solar cells containing a photovoltaic material. Materials presently used for photovoltaics include monocrystalline silicon, polycrystalline silicon, amorphous silicon, cadmium telluride, and copper indium gallium selenide/sulfide. Due to the increased demand for renewable energy sources, the manufacturing of solar cells and photovoltaic arrays has advanced considerably in recent years.

Solar photovoltaics is a sustainable energy source.[126] By the end of 2011, a total of 71.1 GW[127] had been installed, sufficient to generate 85 TWh/year.[128] And by end of 2012, the 100 GW installed capacity milestone was achieved.[129] Solar photovoltaics is now, after hydro and wind power, the third most important renewable energy source in terms of globally installed capacity. More than 100 countries use solar PV. Installations may be ground-mounted (and sometimes integrated with farming and grazing) or built into the roof or walls of a building (either building-integrated photovoltaics or simply rooftop).

Driven by advances in technology and increases in manufacturing scale and sophistication, the cost of photovoltaics has declined steadily since the first solar cells were manufactured,[130] and the levelised cost of electricity (LCOE) from PV is competitive with conventional electricity sources in an expanding list of geographic regions. Net metering and financial incentives, such as preferential feed-in tariffs for solar-generated electricity, have supported solar PV installations in many countries.[131] The Energy Payback Time (EPBT), also known as energy amortization, depends on the location's annual solar insolation and temperature profile, as well as on the used type of PV-technology. For conventional crystalline silicon photovoltaics, the EPBT is higher than for thin-film technologies such as CdTe-PV or CPV-systems. Moreover, the payback time decreased in the recent years due to a number of improvements such as solar cell efficiency and more economic manufacturing processes. As of 2014, photovoltaics recoup on average the energy needed to manufacture them in 0.7 to 2 years. This results in about 95% of net-clean energy produced by a solar rooftop PV system over a 30-year life-time.[132]:30

Biofuels

Bioethanol is an alcohol made by fermentation, mostly from carbohydrates produced in sugar or starch crops such as corn or sugarcane. Cellulosic biomass, derived from non-food sources, such as trees and grasses, is also being developed as a feedstock for ethanol production. Ethanol can be used as a fuel for vehicles in its pure form, but it is usually used as a gasoline additive to increase octane and improve vehicle emissions. Bioethanol is widely used in the USA and in Brazil. Current plant design does not provide for converting the lignin portion of plant raw materials to fuel components by fermentation.

Biodiesel is made from vegetable oils and animal fats. Biodiesel can be used as a fuel for vehicles in its pure form, but it is usually used as a diesel additive to reduce levels of particulates, carbon monoxide, and hydrocarbons from diesel-powered vehicles. Biodiesel is produced from oils or fats using transesterification and is the most common biofuel in Europe.

In 2010, worldwide biofuel production reached 105 billion liters (28 billion gallons US), up 17% from 2009,[133] and biofuels provided 2.7% of the world's fuels for road transport, a contribution largely made up of ethanol and biodiesel.[citation needed] Global ethanol fuel production reached 86 billion liters (23 billion gallons US) in 2010, with the United States and Brazil as the world's top producers, accounting together for 90% of global production. The world's largest biodiesel producer is the European Union, accounting for 53% of all biodiesel production in 2010.[133] As of 2011, mandates for blending biofuels exist in 31 countries at the national level and in 29 states or provinces.[114] The International Energy Agency has a goal for biofuels to meet more than a quarter of world demand for transportation fuels by 2050 to reduce dependence on petroleum and coal.[134]

Geothermal

Earth's internal heat is thermal energy generated from radioactive decay and continual heat loss from Earth's formation. Temperatures at the core-mantle boundary may reach over 4000 °C (7,200 °F).[136] The high temperature and pressure in Earth's interior cause some rock to melt and solid mantle to behave plastically, resulting in portions of mantle convecting upward since it is lighter than the surrounding rock. Rock and water is heated in the crust, sometimes up to 370 °C (700 °F).[137]

From hot springs, geothermal energy has been used for bathing since Paleolithic times and for space heating since ancient Roman times, but it is now better known for electricity generation. Worldwide, 11,400 megawatts (MW) of geothermal power is online in 24 countries in 2012.[138] An additional 28 gigawatts of direct geothermal heating capacity is installed for district heating, space heating, spas, industrial processes, desalination and agricultural applications in 2010.[139]

Geothermal power is cost effective, reliable, sustainable, and environmentally friendly,[140] but has historically been limited to areas near tectonic plate boundaries. Recent technological advances have dramatically expanded the range and size of viable resources, especially for applications such as home heating, opening a potential for widespread exploitation. Geothermal wells release greenhouse gases trapped deep within the earth, but these emissions are much lower per energy unit than those of fossil fuels. As a result, geothermal power has the potential to help mitigate global warming if widely deployed in place of fossil fuels.

The Earth's geothermal resources are theoretically more than adequate to supply humanity's energy needs, but only a very small fraction may be profitably exploited. Drilling and exploration for deep resources is very expensive. Forecasts for the future of geothermal power depend on assumptions about technology, energy prices, subsidies, and interest rates. Pilot programs like EWEB's customer opt in Green Power Program [141] show that customers would be willing to pay a little more for a renewable energy source like geothermal. But as a result of government assisted research and industry experience, the cost of generating geothermal power has decreased by 25% over the past two decades.[142] In 2001, geothermal energy cost between two and ten US cents per kWh.[143]

100% renewable energy

The incentive to use 100% renewable energy, for electricity, transport, or even total primary energy supply globally, has been motivated by global warming and other ecological as well as economic concerns. Renewable energy use has grown much faster than anyone anticipated.[144] The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change has said that there are few fundamental technological limits to integrating a portfolio of renewable energy technologies to meet most of total global energy demand.[145] At the national level, at least 30 nations around the world already have renewable energy contributing more than 20% of energy supply. Also, Professors S. Pacala and Robert H. Socolow have developed a series of “stabilization wedges” that can allow us to maintain our quality of life while avoiding catastrophic climate change, and "renewable energy sources," in aggregate, constitute the largest number of their "wedges." [146]Mark Z. Jacobson says producing all new energy with wind power, solar power, and hydropower by 2030 is feasible and existing energy supply arrangements could be replaced by 2050. Barriers to implementing the renewable energy plan are seen to be "primarily social and political, not technological or economic". Jacobson says that energy costs with a wind, solar, water system should be similar to today's energy costs.[147]

Similarly, in the United States, the independent National Research Council has noted that “sufficient domestic renewable resources exist to allow renewable electricity to play a significant role in future electricity generation and thus help confront issues related to climate change, energy security, and the escalation of energy costs … Renewable energy is an attractive option because renewable resources available in the United States, taken collectively, can supply significantly greater amounts of electricity than the total current or projected domestic demand." .[148]

Critics of the "100% renewable energy" approach include Vaclav Smil and James E. Hansen. Smil and Hansen are concerned about the variable output of solar and wind power, but many other scientists and engineers have analysed this situation and said that the electricity grid can cope.[149]

Increased energy efficiency

A spiral-type integrated compact fluorescent lamp, which has been popular among North American consumers since its introduction in the mid-1990s.[150]

Efficient energy use, simply called energy efficiency, is the goal of efforts to reduce the amount of energy required to provide products and services. For example, insulating a home allows a building to use less heating and cooling energy to achieve and maintain a comfortable temperature. Installing fluorescent lights or natural skylights reduces the amount of energy required to attain the same level of illumination compared to using traditional incandescent light bulbs. Compact fluorescent lights use two-thirds less energy and may last 6 to 10 times longer than incandescent lights. Improvements in energy efficiency are most often achieved by adopting an efficient technology or production process.[152]

There are various motivations to improve energy efficiency. Reducing energy use reduces energy costs and may result in a financial cost saving to consumers if the energy savings offset any additional costs of implementing an energy efficient technology. Reducing energy use is also seen as a key solution to the problem of reducing emissions. According to the International Energy Agency, improved energy efficiency in buildings, industrial processes and transportation could reduce the world's energy needs in 2050 by one third, and help control global emissions of greenhouse gases.[153]

Energy efficiency and renewable energy are said to be the twin pillars of sustainable energy policy.[154] In many countries energy efficiency is also seen to have a national security benefit because it can be used to reduce the level of energy imports from foreign countries and may slow down the rate at which domestic energy resources are depleted.

Transmission

While new sources of energy are only rarely discovered or made possible by new technology, distribution technology continually evolves.[155] The use of fuel cells in cars, for example, is an anticipated delivery technology.[156] This section presents the various delivery technologies that have been important to historic energy development. They all rely in way on the energy sources listed in the previous section.

Shipping and pipelines

Shipping is a flexible delivery technology that is used in the whole range of energy development regimes from primitive to highly advanced. Currently, coal, petroleum and their derivatives are delivered by shipping via boat, rail, or road. Petroleum and natural gas may also be delivered via pipeline and coal via a Slurry pipeline. Refined hydrocarbon fuels such as gasoline and LPG may also be delivered via aircraft. Natural gas pipelines must maintain a certain minimum pressure to function correctly. Ethanol's corrosive properties make it harder to build ethanol pipelines. The higher costs of ethanol transportation and storage are often prohibitive.[157] Geomagnetically induced currents, seen as interfering with the normal operation of long buried pipeline systems, are a manifestation[158][159] at ground level of space weather that occur due to time-varying ionospheric source fields and the conductivity of the Earth.Wired energy transfer

Industrialised countries such as Canada, the US, and Australia are among the highest per capita consumers of electricity in the world, which is possible thanks to a widespread electrical distribution network. The US grid is one of the most advanced, although infrastructure maintenance is becoming a problem. CurrentEnergy provides a realtime overview of the electricity supply and demand for California, Texas, and the Northeast of the US. African countries with small scale electrical grids have a correspondingly low annual per capita usage of electricity. One of the most powerful power grids in the world supplies power to the state of Queensland, Australia.

Wireless energy transfer

Wireless energy transfer is a process whereby electrical energy is transmitted from a power source to an electrical load that does not have a built-in power source, without the use of interconnecting wires.

See also: World Wireless System

Storage

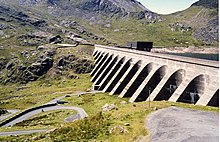

The Ffestiniog Power Station in Wales, United Kingdom. Pumped-storage hydroelectricity (PSH) is used for grid energy storage.

All forms of energy are either potential energy (e.g. Chemical, gravitational, electrical energy, temperature differential, latent heat, etc.) or kinetic energy (e.g. momentum). Some technologies provide only short-term energy storage, and others can be very long-term such as power to gas using hydrogen or methane and the storage of heat or cold between opposing seasons in deep aquifers or bedrock. A wind-up clock stores potential energy (in this case mechanical, in the spring tension), a battery stores readily convertible chemical energy to operate a mobile phone, and a hydroelectric dam stores energy in a reservoir as gravitational potential energy. Ice storage tanks store ice (thermal energy in the form of latent heat) at night to meet peak demand for cooling. Fossil fuels such as coal and gasoline store ancient energy derived from sunlight by organisms that later died, became buried and over time were then converted into these fuels. Even food (which is made by the same process as fossil fuels) is a form of energy stored in chemical form.

History of energy development

Energy generators past and present at Doel, Belgium: 17th century windmill Scheldemolen and 20th century Doel Nuclear Power Station

Since prehistory, when humanity discovered fire to warm up and roast food, through the Middle Ages in which populations built windmills to grind the wheat, until the modern era in which nations can get electricity splitting the atom. Man has sought endlessly for energy sources[note 21] from which to draw profit, which have been the fossil fuels, on one hand the coal to fuel the steam engines run industrial rails as well as maintain households, and secondly, the oil and its derivatives in the industry and transportation (primarily automotive), although have lived with smaller-scale exploitation of wind power, hydro and biomass. This model of development, however, is based on the depletion of fossil resources from periods of millions years without possibility for replacement as would be required to maintain. The search for energy sources that are inexhaustible and utilization by industrialized countries to strengthen their national economies by reducing its dependence on fossil fuels,[note 22] has led to the adoption of nuclear energy and those with sufficient water resources, the intensive hydraulic use of their waterways.

Since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, the question of the future of energy supplies has been of interest. In 1865, William Stanley Jevons published The Coal Question in which he saw that the reserves of coal were being depleted and that oil was an ineffective replacement. In 1914, U.S. Bureau of Mines stated that the total production was 5.7 billion barrels (910,000,000 m3). In 1956, Geophysicist M. King Hubbert deduces that U.S. oil production will peak between 1965 and 1970 (peaked in 1971) and that oil production will peak "within half a century" on the basis of 1956 data.[note 23] In 1989, predicted peak by Colin Campbell[160] In 2004, OPEC estimated, with substantial investments, it would nearly double oil output by 2025[161]

Sustainability

The environmental movement has emphasized sustainability of energy use and development.[162] Renewable energy is sustainable in its production; the available supply will not be diminished for the foreseeable future - millions or billions of years. "Sustainability" also refers to the ability of the environment to cope with waste products, especially air pollution. Sources which have no direct waste products (such as wind, solar, and hydropower) are brought up on this point. With global demand for energy growing, the need to adopt various energy sources is growing. Energy conservation is an alternative or complementary process to energy development. It reduces the demand for energy by using it efficiently.Resilience

Some observers contend that idea of "energy independence" is an unrealistic[note 24] and opaque concept.[163] The alternative offer of "energy resilience" is a goal aligned with economic, security, and energy realities. The notion of resilience in energy was detailed in the 1982 book Brittle Power: Energy Strategy for National Security.[164] The authors argued that simply switching to domestic energy would not be secure inherently because the true weakness is the interdependent and vulnerable energy infrastructure of the United States. Key aspects such as gas lines and the electrical power grid are centralized and easily susceptible to disruption. They conclude that a "resilient energy supply" is necessary for both national security and the environment. They recommend a focus on energy efficiency and renewable energy that is decentralized.[165]

In 2008, former Intel Corporation Chairman and CEO Andrew Grove looked to energy resilience, arguing that complete independence is unfeasible given the global market for energy.[166] He describes energy resilience as the ability to adjust to interruptions in the supply of energy. To that end, he suggests the U.S. make greater use of electricity.[167] Electricity can be produced from a variety of sources. A diverse energy supply will be less impacted by the disruption in supply of any one source. He reasons that another feature of electrification is that electricity is "sticky" – meaning the electricity produced in the U.S. is to stay there because it cannot be transported overseas. According to Grove, a key aspect of advancing electrification and energy resilience will be converting the U.S. automotive fleet from gasoline-powered to electric-powered. This, in turn, will require the modernization and expansion of the electrical power grid. As organizations such as the Reform Institute have pointed out, advancements associated with the developing smart grid would facilitate the ability of the grid to absorb vehicles en masse connecting to it to charge their batteries.[168]

Present and Future

Outlook—World Energy Consumption by Fuel (as of 2011)[169]

Liquid fuels incl. Biofuels Coal Natural Gas

Renewable fuels Nuclear fuels

Liquid fuels incl. Biofuels Coal Natural Gas

Renewable fuels Nuclear fuels

Increasing share of energy consumption by developing nations[170]

Industrialized nations

Developing nations

EE/Former Soviet Union

Industrialized nations

Developing nations

EE/Former Soviet Union

Extrapolations from current knowledge to the future offer a choice of energy futures.[171] Predictions parallel the Malthusian catastrophe hypothesis. Numerous are complex models based scenarios as pioneered by Limits to Growth. Modeling approaches offer ways to analyze diverse strategies, and hopefully find a road to rapid and sustainable development of humanity. Short term energy crises are also a concern of energy development. Extrapolations lack plausibility, particularly when they predict a continual increase in oil consumption.[citation needed]

Energy production usually requires an energy investment. Drilling for oil or building a wind power plant requires energy. The fossil fuel resources (see above) that are left are often increasingly difficult to extract and convert. They may thus require increasingly higher energy investments. If investment is greater than the energy produced, than the resource; It is no longer an effective energy source.[172][note 25] This means that resources, the wasteful ones, are not used effectively for energy production.[note 26] Such resources can be exploited economically in order to produce raw materials;[note 27] They then become ordinary mining reserves, economically recoverable are not a positive energy sources. New technology may ameliorate this problem if it can lower the energy investment required to extract and convert the resources, although ultimately basic physics sets limits that cannot be exceeded.

Between 1950 and 1984, as the Green Revolution transformed agriculture around the globe, world grain production increased by 250%. The energy for the Green Revolution was provided by fossil fuels in the form of fertilizers (natural gas), pesticides (oil), and hydrocarbon fueled irrigation.[173] The peaking of world hydrocarbon production (peak oil) may lead to significant changes, and require sustainable methods of production.[174] One vision of a sustainable energy future involves all human structures on the earth's surface (i.e., buildings, vehicles and roads) doing artificial photosynthesis (using sunlight to split water as a source of hydrogen and absorbing carbon dioxide to make fertilizer) efficiently than plants.[175]

With contemporary space industry's economic activity[176][177] and the related private spaceflight, with the manufacturing industries, that go into Earth's orbit or beyond, delivering them to those regions will require further energy development.[178][179][180][181] Commercialization of space includes satellite navigation systems, satellite television and satellite radio; investments estimated to be $50.8 billion.[182] There are the spaceports of Sweden's gateway, Curaçao's gateway,[note 28] Malaysia's gateway, and America's gateway[note 29] that plans to make personal and commercial suborbital spaceflight for space tourism, space hubs,[note 30] space research, and science education, in-addition to contribute to Earth-based cross-industry innovation. Researchers have contemplated space-based solar power for collecting solar power in space for use on Earth.[note 31][note 32] Space-based solar power only differ from solar and other similar radiant energy collection methods in that the means used to collect energy would reside on an orbiting satellite instead of on Earth's surface. Some projected benefits of such a system are a higher collection rate and a longer collection period due to the lack of a diffusing and refracting atmosphere and nighttime in space.[note 33]