Sectarianism is a debated concept. Some scholars and journalists define it as pre-existing fixed communal categories in society, and use it to explain political, cultural, or religious conflicts between groups. Others conceive of sectarianism as a set of social practices where daily life is organized on the basis of communal norms and rules that individuals strategically use and transcend. This definition highlights the co-constitutive aspect of sectarianism and people's agency, as opposed to understanding sectarianism as being fixed and incompatible communal boundaries.

While sectarianism is often labelled as religious or political, the reality of a sectarian situation is usually much more complex. In its most basic form, sectarianism has been defined as, 'the existence, within a locality, of two or more divided and actively competing communal identities, resulting in a strong sense of dualism which unremittingly transcends commonality, and is both culturally and physically manifest.'

Definition

The term "sectarianism" is defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as "excessive attachment to a particular sect or party, especially in religion". The phrase "sectarian conflict" usually refers to violent conflict along religious or political lines, such as the conflicts between Nationalists and Unionists in Northern Ireland (religious and class-divisions may play major roles as well). It may also refer to general philosophical, political disparity between different schools of thought, such as that between Shia and Sunni Muslims. Non-sectarians see free association and tolerance of different beliefs as the cornerstones to successful, peaceful human interaction. They adopt political and religious pluralism.

Polemics against the term "sectarianism"

Some scholars identify the problems with using the term "sectarianism" in articles. Western mainstream media and politicians often presume "sectarianism" as ancient and long-lasting. For example, Obama in his final State of the Union address phrased the sectarian violence in the Middle East as "rooted in conflicts that dated back millennia", but many pointed out that some sectarian tensions don't even date back a decade. "Sectarianism" is also too ambiguous, which makes it a slogan whose meanings are up to the observers. Scholars argued that the use of term "sectarianism" has become a catch-all explanation to conflicts, which drives analytical attention away from underlying political and socioeconomic issues, lacks coherence, and is often associated with emotional negativity. Many scholars find the term "sectarianism" problematic, and therefore three alternatives are proposed.

Alternative: Sectarianization

Hashemi and Postel and other scholars differentiate between "sectarianism" and "sectarianization". While "sectarianism" describes antipathy, prejudice, and discrimination between subdivisions within a group, e.g. based on their religious or ethnic identity, the latter describes a process mobilized by political actors operating within authoritarian contexts to pursue their political goals that involve popular mobilization around religious or identity markers. The use of the word sectarianism to explain sectarian violence and its upsurge in i.e. the Middle East is insufficient, as it does not take into account complex political realities. In the past and present, religious identities have been politicized and mobilized by state actors inside and outside of the Middle East in pursuit of political gain and power. The term sectarianization conceptualizes this notion. Sectarianization is an active, multi-layered process and a set of practices, not a static condition, that is set in motion and shaped by political actors pursuing political goals. The sectarianization thesis focuses on the intersection of politics and sectarian identity from a top-down state-centric perspective. Sectarianization would be more precise if you're referring to how sectarian identities and divisions are systematically created or reinforced by the state or other institutions, while sectarianism would be more appropriate when discussing the ideology or attitude that underpins sectarian divisions. While religious identity is salient in the Middle East and has contributed to and intensified conflicts across the region, it is the politicization and mobilization of popular sentiments around certain identity markers ("sectarianization") that explains the extent and upsurge of sectarian violence in the Middle East. The Ottoman Tanzimat, European colonialism and authoritarianism are key in the process of sectarianization in the Middle East.

Alternative: Sectarian as a prefix

Haddad argues "sectarianism" cannot capture sectarian relations in reality nor represent the complex expressions of sectarian identities. Haddad calls for an abandonment of -ism in "sectarianism" in scholarly research as it "has overshadowed the root" and direct use of 'sectarian' as a qualifier to "direct our analytical focus towards understanding sectarian identity". Sectarian identity is "simultaneously formulated along four overlapping, interconnected and mutually informing dimensions: doctrinal, subnational, national, and transnational". The relevance of these factors is context-dependent and works on four layers in chorus. The multi-layered work provides more clarity and enables more accurate diagnoses of problems at certain dimensions to find more specific solutions.

Alternative: Sextarianism

In her book Sextarianism, Mikdashi emphasizes the relationship between sect, sex and sexuality. She argues that sectarianism cannot be studied in isolation, because the practice of sectarianism always goes hand in hand with the practice of sexism. Moreover, she states that the category 'sect' is already a patriarchal inheritance. For this reason she proposes the term "sextarianism". Sex, sexuality and sect together define citizenship, and, since the concept of citizenship is the basis of the modern nation-state, sextarianism therefore forms the basis for the legal bureaucratic systems of the state and thus for state power. It emphasizes how state power articulates, disarticulates, and manages sexual difference bureaucratically, ideologically, and legally. To further illustrate the dimensions by which the dynamics of sextarianism in Lebanese society can be explained, Mikdashi refers to two central concepts: Evangelical Secularism, and the Epidermal State.

Based on Carole Pateman, sexual difference is political difference, while sexual difference is not merely a biological or cultural distinction but a fundamental mechanism of power relations. She argues that sexual difference functions as a process through which sectarian, gendered, and sexual positions are structurally produced, represented, imagined, desired, and managed. In this view, the construction of sexual difference is inseparable from political structures, shaping not only individual identities but also the broader organization of social and political life.

Dimension of Sextarianism: Evangelical Secularism and the Epidermal State

Sextarianism builds on Joan Scott’s theorization of the constitutive nature of sexual difference to the history of secularism. According to Mikdashi, sectarianism provided her with the chance to examine the Lebanese state without separating or favoring sectarian differences from sexual differences. This approach is rooted in the ways the state regulates and creates both sexual and sectarian distinctions. The Lebanese legal system shapes sexual difference across various areas of law, with sexual difference playing a far more significant role as a legal category than sectarian difference. The Lebanese state handles both sexual and sectarian differences through its judicial and governmental/bureaucratic structures. Mikdashi furthermore ties this development to the concepts of the evangelical and state based secularism which by emphasising the sectarian sphere through its sovereignty, securitisation, and citizenship laws, manages to enshrine its view into society. The second important component - the epidermal state - is used by Mikdashi to show the locus and mode with which states manifest their power to enforce sextarianism.

Mikdashi also refers to the idea that sextarianism unpacks how heterosexuality, the sex binary, and civil and criminal law are key to secularism’s management of sexual and religious difference, with secularism’s investment in sex manifesting as the regulation of straight and queer sexualities and a sex-gender binary system.

Alternative: Practicing Sectarianism

In their book "Practicing Sectarianism" Deep, Nalbantian and Sbaiti (2022) emphasise that sectarianism does not need to remain a historical/anthropological pre-requisite for analyses but benefits from an understanding of the micro-level experiences of individuals, and how they relate, react, and contradict a static framing of "political" sectarianism. They also highlight that the concept - at least when focussing on the prominent example of Lebanon - should be understood as multi-dimensional with (1) political sectarianism, (2) Civil Sectarianism, and (3) Socio-Economic Sectarianism.

Intersectionality in Sectarianism

The analytical framework of intersectionality in examining sectarianism has gained increasing prominence in the study of this subject. Intersectionality highlights the nature of religious, ethnic, political, and social identities in contexts marked by sectarian tensions and conflicts. Acknowledging that individuals' experiences of sectarianism are shaped not only by their religious affiliation or other sectarian categories but also by other dimensions such as sex, class, and nationality among others, are essentially contributing to those experiences.

Religious Dimension

Intersectionality reveals that factors like sex, ethnicity, and socioeconomic status intersect with religious identity to shape individuals' experiences of sectarianism. Authors such as Maya Mikdashi introduced the concept of 'Sextarianism', particularly showing how the role of gender is crucially influencing the individual's experience of religious sectarian differences in political sectarian systems such as in Lebanon. In the case of Sectarianism in Lebanon, she highlights how Sextarian differences are decisive vectors in determining woman's experiences of power and sovereignty in a political sectarian system.

Taqiyya

Some adherents of Islam practice Taqiyya to safeguard themselves from religious persecution, within Islam and in other religious scenarios.

Political Dimension

In the political dimensions, the intersectional lens recognizes the intricate connections between political identities and other social categories. Political parties or other factions may exploit religious divisions for political gain, exacerbating sectarian tensions. Intersectionality helps to understand how for instance political affiliations intersect with factors such as socioeconomic status and regional background, providing insights into the motivation behind political mobilization and the dynamics of power in sectarian settings.

Implications for Communities

The intersectionality of sectarianism has profound implications for affected communities, particularly for individuals who belong to multiple marginalized groups such as women, migrants, and marginalized ethnicities living under sectarian systems. The recognition of these intersecting forms of discrimination and marginalization is decisive for developing inclusive strategies to promote peace, tolerance, and increased social cohesion within diverse societies.

Political sectarianism

Sectarianism in the 21st century

Sectarian tendencies in politics are visible in countries and cities associated with sectarian violence in the present, and the past. Notable examples where sectarianism affects lives are street-art expression, urban planning, and sports club affiliation.

United Kingdom

Across the United Kingdom, Scottish and Irish sectarian tendencies are often reflected in team-sport competitions. Affiliations are regarded as a latent representation of sectarianism tendencies. (Since the early 1900s, cricket teams were established via patronage of sectarian affiliated landlords. In response to the Protestant representation of the sport, many Catholic schools founded their own Cricket schools.) Modern day examples include tensions in sports such as football and have led to the passing of the "Offensive Behaviour at Football and Threatening Communications (Scotland) Act 2012".

Authoritarian regimes

In recent years, authoritarian regimes have been particularly prone to sectarianization. This is because their key strategy of survival lies in manipulating sectarian identities to deflect demands for change and justice, and preserve and perpetuate their power. The sectarianization as a theory and process that extended beyond the Middle East was introduced by Saleena Saleem. Christian communities, and other religious and ethnic minorities in the Middle East, have been socially, economically and politically excluded and harmed primarily by regimes that focus on "securing power and manipulating their base by appeals to Arab nationalism and/or to Islam". An example of this is the Middle Eastern regional response to the Iranian revolution of 1979. Middle Eastern dictatorships backed by the United States, especially Saudi Arabia, feared that the spread of the revolutionary spirit and ideology would affect their power and dominance in the region. Therefore, efforts were made to undermine the Iranian revolution by labeling it as a Shi’a conspiracy to corrupt the Sunni Islamic tradition. This was followed by a rise of anti-Shi’a sentiments across the region and a deterioration of Shi'a-Sunni relations, impelled by funds from the Gulf states. Therefore, the process of sectarianization, the mobilization and politicization of sectarian identities, is a political tool for authoritarian regimes to perpetuate their power and justify violence. Western powers indirectly take part in the process of sectarianization by supporting undemocratic regimes in the Middle East. As Nader Hashemi asserts:

The U.S. invasion of Iraq; the support of various Western governments for the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, which commits war crime upon war crime in Yemen and disseminates poisonous sectarian propaganda throughout the Sunni world; not to mention longstanding Western support for highly repressive dictators who manipulate sectarian fears and anxieties as a strategy of control and regime survival – the "ancient hatreds" narrative [between Sunnis and Shi’as] washes this all away and lays the blame for the regionʹs problems on supposedly trans-historical religious passions. Itʹs absurd in the extreme and an exercise in bad faith.

Approaches to Study Sectarian Identities in authoritarian regimes

Scholars have adopted three approaches to study sectarian discourses: primordialism, instrumentalism, and constructivism. Primordialism sees sectarian identity as rotted in biology and ingrained in history and culture. Makdisi describes the process of bringing the sectarian discourses back to early Islamic history as "pervasive medievalization". The centuries-old narrative is problematic as it treats sectarian identities in the Middle East as sui generis instead of modern collective identities. Scholars should be cautious of sectarian essentialism and Middle East exceptionalism the primordial narrative reinforces since primordialism suggests sectarian tensions persist while theological differences do not guarantee conflicts. Instrumentalism emphasizes that ruling elites manipulate identities to create violent conflicts for their interests. Instrumentalists see the Sunni-Shi'a divide as a modern invention and challenge the myths of primordial narratives since sectarian harmony have existed for centuries. Constructivism is in the middle ground of primordialism and instrumentalism.

Religious sectarianism

Wherever people of different religions live in close proximity to each other, religious sectarianism can often be found in varying forms and degrees. In some areas, religious sectarians (for example Protestant and Catholic Christians) now exist peacefully side by side for the most part, although these differences have resulted in violence, death, and outright warfare as recently as the 1990s. Probably the best-known example in recent times were The Troubles.

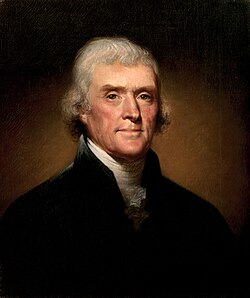

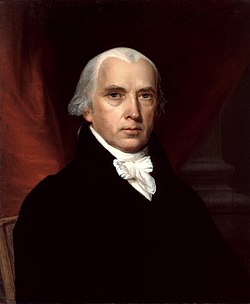

Catholic-Protestant sectarianism has also been a factor in U.S. presidential campaigns. Prior to John F. Kennedy, only one Catholic (Al Smith) had ever been a major party presidential nominee, and he had been solidly defeated largely because of claims based on his Catholicism. JFK chose to tackle the sectarian issue head-on during the West Virginia primary, but that only sufficed to win him barely enough Protestant votes to eventually win the presidency by one of the narrowest margins ever.

Within Islam, there has been dilemmas at various periods between Sunnis and Shias; Shias consider Sunnis to be false, due to their refusal to accept the first caliph as Ali and accept all following descendants of him as infallible and divinely guided. Many Sunni religious leaders, including those inspired by Wahhabism and other ideologies have declared Shias to be heretics or apostates.

Europe

In some countries where the Reformation was successful, there was persecution of Roman Catholics. This was motivated by the perception that Catholics retained allegiance to a 'foreign' power (the papacy or the Vatican), causing them to be regarded with suspicion. Sometimes this mistrust manifested itself in Catholics being subjected to restrictions and discrimination, which itself led to further conflict. For example, before Catholic Emancipation was introduced with the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829, Catholics were forbidden from voting, becoming MP's or buying land in Ireland.

Ireland

Protestant-Catholic sectarianism is prominent in Irish history; during the period of English (and later British) rule, Protestant settlers from Britain were "planted" in Ireland, which along with the Protestant Reformation led to increasing sectarian tensions between Irish Catholics and British Protestants. These tensions eventually boiled over into widespread violence during the Irish Rebellion of 1641. At the end of that war the lands of Catholics were confiscated with over ten million acres granted to new English owners under the Act for the Settlement of Ireland 1652. The Cromwellian conquest of Ireland (1649–1653) saw a series of massacres perpetrated by the Protestant New Model Army against Catholic English royalists and Irish civilians. Sectarianism between Catholics and Protestants continued in the Kingdom of Ireland, with the Irish Rebellion of 1798 against British rule leading to more sectarian violence in the island. The British response to the rebellion which included the public executions of dozens of suspected rebels in Dunlavin and Carnew, also inflamed sectarian sentiments.

Northern Ireland

After the Partition of Ireland in 1922, Northern Ireland witnessed decades of intensified conflict, tension, and sporadic violence (see The Troubles in Ulster (1920–1922) and The Troubles) between the dominant Protestant majority and the Catholic minority. In 1969 the Northern Ireland Civil Rights Association was formed to support civil rights and end discrimination (based on religion) in voting rights (see Gerrymandering), housing allocation and employment. Also in 1969, 25 years of violence erupted, becoming what is known as “The Troubles” between Irish Republicans whose goal is a United Ireland and Ulster loyalists who wish for Northern Ireland to remain a part of the United Kingdom. The conflict was primarily fought over the existence of the Northern Irish state rather than religion, though sectarian relations within Northern Ireland fueled the conflict. However, religion is commonly used as a marker to differentiate the two sides of the community. Most Catholics favour the nationalist, and to some degree, republican, goal of unity with the Republic of Ireland, whereas most Protestants favour Northern Ireland continuing the union with Great Britain.

England

In June 1780 a series of riots (see the Gordon Riots) occurred in London motivated by anti-Catholic sentiment. These riots were described as being the most destructive in the history of London and resulted in approximately 300-700 deaths. A long history of politically and religious motivated sectarian violence already existed in Ireland (see Irish Rebellions). The sectarian divisions related to the "Irish question" influenced local constituent politics in England.

Liverpool is an English city sometimes associated with sectarian politics. Halfway through the 19th century, Liverpool faced a wave of mass-immigration from Irish Catholics as a consequence of the Great Famine in Ireland. Most of the Irish-Catholic immigrants were unskilled workers and aligned themselves with the Labour party. The Labour-Catholic party saw a larger political electorate in the many Liverpool-Irish, and often ran on the slogan of "Home Rule" - the independence of Ireland, to gain the support of Irish voters. During the first half of the 20th century, Liverpool politics were divided not only between Catholics and Protestants, but between two polarized groups consisting of multiple identities: Catholic-Liberal-Labour and Protestant-Conservative-Tory/Orangeists.

From early 1900 onwards, the polarized Catholic Labour and Protestant Conservative affiliations gradually broke apart and created the opportunity for mixed alliances. The Irish National party gained its first electoral victory in 1875, and kept growing until the realization of Irish independence in 1921, after which it became less reliant on Labour support. On the Protestant side, Tory opposition in 1902 to vote in line with Protestant proposed bills indicated a split between the working class Protestants and the Tory party, which were regarded as "too distant" from its electorate.

After the First and Second World War, religiously mixed battalions provided a counterweight to anti-Roman Catholic and anti-Protestant propaganda from either side. While the IRA-bombing in 1939 (see S-Plan) somewhat increased violence between the Irish-Catholic associated Labour party and the Conservative Protestants, the German May Blitz destroyed property of more than 40.000 households. Rebuilding Liverpool after the war created a new sense of community across religious lines. Inter-church relations increased as a response as well, as seen through the warming up of relations between Archbishop Worlock and Anglican Bishop David Sheppard after 1976, a symbol of decreasing religious hostility. The increase in education rates and the rise of trade and labour unions shifted religious affiliation to class affiliation further, which allowed Protestant and catholic affiliates under a Labour umbrella in politics. In the 1980s, class division had outgrown religious division, replacing religious sectarianism with class struggle. Growing rates of non-English immigration from other parts of the Commonwealth near the 21st century also provides new political lines of division in identity affiliation.

Northern Ireland has introduced a Private Day of Reflection, since 2007, to mark the transition to a post-[sectarian] conflict society, an initiative of the cross-community Healing Through Remembering organization and research project.

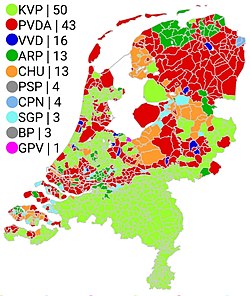

The Netherlands

Because of the Netherlands's diversity of Protestants, Catholics, as well as politically-oriented elements in society, the country used a system called pillarisation (verzuiling) whereby each religious-socioeconomic segment would only use services for their own pillar (such as media, schools or labor unions) and politically vote for the parties representing their own. This system remained strong until the 1960s, but some institutions continue to be divided as a legacy of pillarisation.

Ex-Yugoslavia

The civil wars in ex-Yugoslav countries which followed its breakup in the 1990s have been heavily tinged with sectarianism. Croats and Slovenes have traditionally belonged to Catholicism, Serbs and Macedonians to Eastern Orthodoxy, and Bosniaks and Kosovo Albanians to Islam. Religious affiliation served as a marker of group identity in this conflict, despite relatively low rates of religious practice and belief among these various groups after decades of de facto state atheism in communist Yugoslavia.

Africa

Over 1,000 Muslims and Christians were killed in the sectarian violence in the Central African Republic in 2013–2014. Nearly 1 million people, a quarter of the population, were displaced.

Australia

Sectarianism in Australia is a historical legacy from the 18th, 19th and 20th centuries, between Irish Catholics and Protestants of mainly Scotch Irish and English descent. It has largely faded in the 21st century.

In the late 20th and early 21st centuries, religious tensions were more centered between Muslim immigrants and non-Muslim nationalists, amid the backdrop of the war on terror.

Asia

Japan

For the violent conflict between Buddhist sects in Japan, see Japanese Buddhism.

Pakistan

Pakistan, one of the largest Muslim countries the world, has seen serious Shia-Sunni sectarian violence. Almost 80-85% of Pakistan's Muslim population is Sunni, and another 15-20% are Shia. However, this Shia minority forms the second largest Shia population of any country, larger than the Shia majority in Iraq.

In the last two decades, as many as 4,000 people are estimated to have died in sectarian fighting in Pakistan, 300 in 2006. Among the culprits blamed for the killing are Al Qaeda working "with local sectarian groups" to kill what they perceive as Shi'a apostates.

Sri Lanka

The BBC reported that "Sri Lanka’s Muslim minority is being targeted by hardline Buddhists. ... There have also been assaults on churches and Christian pastors but it is the Muslims who are the most concerned." Most of the LTTE leaders were captured and gunned down at blank range in May, 2009, after which a genocide of Sri Lankan Tamils in the Northern Province, Sri Lanka has started. Even a book, The Tamil Genocide by Sri Lanka has been written on this genocide. Tamils Against Genocide hired US attorney Bruce Fein to file human rights violation charges against two Sri Lankan officials associated with the civil war in Sri Lanka which has reportedly claimed the lives of thousands of civilians.

Turkey

Ottoman Empire

In 1511, a pro-Shia revolt known as Şahkulu Rebellion was brutally suppressed by the Ottomans: 40,000 were massacred on the order of the sultan.

Republican era (1923-)

Alevis were targeted in various massacres including 1978 Maraş massacre, 1980 Çorum massacre and 1993 Sivas massacre.

During his campaign for the 2023 Turkish presidential election, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu was attacked with sectarian insults in Adıyaman.

Iran

Overview

Sectarianism in Iran has existed for centuries, dating back to the Islamic conquest of the country in early Islamic years and continuing throughout Iranian history until the present. During the Safavid dynasty's reign, sectarianism started to play an important role in shaping the path of the country. During the Safavid rule between 1501 and 1722, Shiism started to evolve and became established as the official state religion, leading to the creation of the first religiously legitimate government since the occultation of the Twelfth imam. This pattern of sectarianism prevailed throughout the Iranian history. The approach that sectarianism has taken after the Iranian 1979 revolution is shifted compared to the earlier periods. Never before the Iranian 1979 revolution did the Shiite leadership gain as much authority. Due to this change, the sectarian timeline in Iran can be divided in pre- and post-Iranian 1979 revolution where the religious leadership changed course.

Pre-1979 Revolution

Shiism has been an important factor in shaping the politics, culture and religion within Iran, long before the Iranian 1979 revolution. During the Safavid dynasty Shiism was established as the official ideology. The establishment of Shiism as an official government ideology opened the doors for clergies to benefit from new cultural, political and religious rights which were denied prior to the Safavid ruling. During the Safavid dynasty Shiism was established as the official ideology. The Safavid rule allowed greater freedom for religious leaders. By establishing Shiism as the state religion, they legitimised the religious authority. After this power establishment, religious leaders started to play a crucial role within the political system but remained socially and economically independent. The monarchial power balance during the Safavid ere changed every few years, resulting in a changing limit of power of the clergies. The tensions concerning power relations of the religious authorities and the ruling power eventually played a pivotal role in the 1906 constitutional revolution which limited the power of the monarch, and increased the power of religious leaders. The 1906 constitutional revolution involved both constitutionalist and anti-constitutionalist clergy leaders. Individuals such as Sayyid Jamal al-Din Va'iz were constitutionalist clergies whereas other clergies such as Mohammed Kazem Yazdi were considered anti-constitutionalist. The establishment of a Shiite government during the Safavid rule resulted in the increase of power within this religious sect. The religious power establishment increased throughout the years and resulted in fundamental changes within the Iranian society in the twentieth century, eventually leading to the establishment of the Shiite Islamic Republic of Iran in 1979.

Post-1979 Revolution: Islamic Republic of Iran

The Iranian 1979 revolution led to the overthrow of the Pahlavi dynasty and the establishment of the Islamic Government of Iran. The governing body of Iran displays clear elements of sectarianism which are visible within different layers of its system. The 1979 revolution led to changes in political system, leading to the establishment of a bureaucratic clergy-regime which has created its own interpretation of the Shia sect in Iran. Religious differentiation is often used by authoritarian regimes to express hostility towards other groups such as ethnic minorities and political opponents. Authoritarian regimes can use religion as a weapon to create an "us and them" paradigm. This leads to hostility amongst the involved parties and takes place internally but also externally. A valid example is the suppression of religious minorities like the Sunnis and Baha-ís. With the establishment of the Islamic Republic of Iran sectarian discourses arose in the Middle-East as the Iranian religious regime has attempted and in some cases succeeded to spread its religious and political ideas in the region. These sectarian labeled issues are politically charged. The most notable Religious leaders in Iran are named Supreme-leaders. Their role has proved to be pivotal in the evolvement of sectarianism within the country and in the region. The following part discusses Iran's supreme-leadership in further detail.

Ruhollah Khomeini and Ali Khamenei

During the Iran-Iraq war, Iran's first supreme-leader, Ayatollah Khomeini called for the participation of all Iranians in the war. His usage of Shia martyrdom led to the creation of a national consensus. In the early aftermath of the Iranian 1979 revolution, Khomeini started to evolve a sectarian tone in his speeches. His focus on Shiism and Shia Islam grew which was also implemented within the changing policies of the country. In one of his speeches Khomeini quoted: "the Path to Jerusalem passes through Karbala." His phrase lead to many different interpretations, leading to turmoil in the region but also within the country. From a religious historic viewpoint, Karbala and Najaf which are both situated in Iraq, serve as important sites for Shia Muslims around the world. By mentioning these two cities, Khomeini led to the creation of Shia expansionism. Khomeini's war with the Iraqi Bath Regime had many underlying reasons and sectarianism can be considered one of the main reasons. The tensions between Iran and Iraq are of course not only sectarian related, but religion is often a weapon used by the Iranian regime to justify its actions. Khomeini's words also resonated in other Arab countries who had been fighting for Palestinian liberation against Israel. By naming Jerusalem, Khomeini expressed his desire for liberating Palestine from the hands of what he later often has named "the enemy of Islam." Iran has supported rebellious groups throughout the region. Its support for Hamas and Hezbollah has resulted in international condemnation. This desire for Shia expansionism did not disappear after Khomeini's death. It can even be argued that sectarian tone within the Islamic Republic of Iran has grown since then. The Friday prayers held in Tehran by Ali Khamenei can be seen as a proof of growing sectarian tone within the regime. Khamenei's speeches are extremely political and sectarian. He often mentions extreme wishes such as the removal of Israel from the world map and fatwas directed towards those opposing the regime.

Iraq

Sunni Iraqi insurgency and foreign Sunni terrorist organizations who came to Iraq after the fall of Saddam Hussein have targeted Shia civilians in sectarian attacks. Following the civil war, the Sunnis have complained of discrimination by Iraq's Shia majority governments, which is bolstered by the news that Sunni detainees were allegedly discovered to have been tortured in a compound used by government forces on 15 November 2005. This sectarianism has fueled a giant level of emigration and internal displacement.

The Shia majority oppression by the Sunni minority has a long history in Iraq. After the fall of the Ottoman Empire, the British government placed a Sunni Hashemite monarchy to the Iraqi throne which suppressed various uprisings against its rule by the Christian Assyrians and Shi'ites.

Syria

Although sectarianism has been described as one of the characteristic features of the Syrian civil war, the narrative of sectarianism already had its origins in Syria's past.

Ottoman rule

The hostilities that took place in 1850 in Aleppo and subsequently in 1860 in Damascus, had many causes and reflected long-standing tensions. However, scholars have claimed that the eruptions of violence can also be partly attributed to the modernizing reforms, the Tanzimat, taking place within the Ottoman Empire, who had been ruling Syria since 1516. The Tanzimat reforms attempted to bring about equality between Muslims and non-Muslims living in the Ottoman Empire. These reforms, combined with European interference on behalf of the Ottoman Christians, caused the non-Muslims to gain privileges and influence.

In the silk trade business, European powers formed ties with local sects. They usually opted for a sect that adhered to a religion similar to the one in their home countries, thus not Muslims. These developments caused new social classes to emerge, consisting of mainly Christians, Druzes and Jews. These social classes stripped the previously existing Muslim classes of their privileges. The involvement of another foreign power, though this time non-European, also had its influence on communal relations in Syria. Ibrahim Pasha of Egypt ruled Syria between 1831 and 1840. His divide-and-rule strategy contributed to the hostilities between the Druze and Maronite community, by arming the Maronite Christians. However, it is noteworthy to mention that different sects did not fight the others out of religious motives, nor did Ibrahim Pasha aim to disrupt society among communal lines. This can also be illustrated by the unification of Druzes and Maronites in their revolts to oust Ibrahim Pasha in 1840. This shows the fluidity of communal alliances and animosities and the different, at times non-religious, reasons that may underline sectarianism.

After Ottoman rule

Before the fall of the Ottoman Empire and the French Mandate in Syria, the Syrian territory had already witnessed massacres on the Maronite Christians, other Christians, Alawites, Shias and Ismailiyas, which had resulted in distrustful sentiments between the members of different sects. In an attempt to protect the minority communities against the majority Sunni population, France, with the command of Henri Gouraud, created five states for the following sects: Armenians, Alawites, Druzes, Maronite Christians and Sunni Muslims. This focus on minorities was new and part of a divide-and-rule strategy of the French, which enhanced and politicized differences between sects. The restructuring by the French caused the Alawite community to advance itself from their marginalized position. In addition to that, the Alawites were also able to obtain a position of power through granting top level positions to family members of the ruling clan or other tribal allies of the Alawite community.

During the period 1961–1980, Syria was not necessarily exclusively ruled by the Alawite sect, but due to efforts of the Sunni Muslim extremist opponents of the Ba’th regime in Syria, it was perceived as such. The Ba’ath regime was being dominated by the Alawite community, as well as were other institutions of power. As a result of this, the regime was considered to be sectarian, which caused the Alawite community to cluster together, as they feared for their position. This period is actually contradictory as Hafez al-Assad tried to create a Syrian Arab nationalism, but the regime was still regarded as sectarian and sectarian identities were reproduced and politicized.

Sectarian tensions that later gave rise to the Syrian civil war, had already appeared in society due to events preceding 1970. For example, President Hafez al-Assad's involvement in the Lebanese civil war by giving political aid to Maronite Christians in Lebanon. This was viewed by many Sunny Muslims as an act of treason, which made them link al-Assad's actions to his Alawite identity. The Muslim Brothers, a part of the Sunni Muslims, used those tensions towards the Alawites as a tool to boost their political agenda and plans. Several assassinations were carried out by the Muslim Brothers, mostly against Alawites, but also against some Sunni Muslims. The failed assassination attempt on President Hafez al-Assad is arguably the most well-known. Part of the animosity between the Alawites and the Sunni Islamists of the Muslim Brothers is due to the secularization of Syria, which the later holds the Alawites in power to be responsible for.

Syrian Civil War

As of 2015, the majority of the Syrian population consisted of Sunni Muslims, namely two-thirds of the population, which can be found throughout the country. The Alawites are the second largest group, which make up around 10 percent of the population. This makes them a ruling minority. The Alawites were originally settled in the highlands of Northwest Syria, but since the twentieth century have spread to places like Latakia, Homs and Damascus. Other groups that can be found in Syria are Christians, among which the Maronite Christians, Druzes and Twelver Shias. Although sectarian identities played a role in the unfolding of events of the Syrian Civil War, the importance of tribal and kinship relationships should not be underestimated, as they can be used to obtain and maintain power and loyalty.

At the start of the protests against President Basher al-Assad in March 2011, there was no sectarian nature or approach involved. The opposition had national, inclusive goals and spoke in the name of a collective Syria, although the protesters being mainly Sunni Muslims. This changed after the protests and the following civil war began to be portrayed in sectarian terms by the regime, as a result of which people started to mobilize along ethnic lines. However, this does not mean that the conflict is solely or primarily a sectarian conflict, as there were also socio-economic factors at play. These socio-economic factors were mainly the result of Basher al-Assad's mismanaged economic restructuring. The conflict has therefore been described as being semi-sectarian, making sectarianism a factor at play in the civil war, but certainly does not stand alone in causing the war and has varied in importance throughout time and place.

In addition to local forces, the role of external actors in the conflict in general as well as the sectarian aspect of the conflict should not be overlooked. Although foreign regimes were first in support of the Free Syrian Army, they eventually ended up supporting sectarian militias with money and arms. However, it has to be said that their sectarian nature did not only attract these flows of support, but they also adopted a more sectarian and Islamic appearance in order to attract this support.

Yemen

Introduction

In Yemen, there have been many clashes between Salafis and Shia Houthis. According to The Washington Post, "In today’s Middle East, activated sectarianism affects the political cost of alliances, making them easier between co-religionists. That helps explain why Sunni-majority states are lining up against Iran, Iraq and Hezbollah over Yemen."

Historically, divisions in Yemen along religious lines (sects) used to be less intense than those in Pakistan, Lebanon, Syria, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and Bahrain. However, the situation has changed dramatically after the Houthi takeover in 2014. Most political forces in Yemen are primarily characterized by regional interests and not by religious sectarianism. Regional interests are, for example, the north's proximity to the Hejaz, the south's coast along the Indian Ocean trade route, and the southeast's oil and gas fields. Yemen's northern population consists for a substantial part of Zaydis, and its southern population predominantly of Shafi’is.[108] Hadhramaut in Yemen's southeast has a distinct Sufi Ba’Alawi profile.

Ottoman era, 1849–1918

Sectarianism reached the region once known as Arabia Felix with the 1911 Treaty of Daan. It divided the Yemen Vilayet into an Ottoman controlled section and an Ottoman-Zaydi controlled section. The former dominated by Sunni Islam and the latter by Zaydi-Shia Islam, thus dividing the Yemen Vilayet along Islamic sectarian lines. Yahya Muhammad Hamid ed-Din became the ruler of the Zaidi community within this Ottoman entity. Before the agreement, inter-communal battles between Shafi’is and Zaydis never occurred in the Yemen Vilayet. After the agreement, sectarian strife still did not surface between religious communities. Feuds between Yemenis were nonsectarian in nature, and Zaydis attacked Ottoman officials not because they were Sunnis.

Following the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the divide between Shafi’is and Zaydis changed with the establishment of the Kingdom of Yemen. Shafi’i scholars were compelled to accept the supreme authority of Yahya Muhammad Hamid ed-Din, and the army “institutionalized the supremacy of the Zaydi tribesman over the Shafi’is”.

Unification period, 1918–1990

Before the 1990 Yemeni unification, the region had never been united as one country. In order to create unity and overcome sectarianism, the myth of Qahtanite was used as a nationalist narrative. Although not all ethnic groups of Yemen fit in this narrative, such as the Al-Akhdam and the Teimanim. The latter established a Jewish kingdom in ancient Yemen, the only one ever created outside Palestine. A massacre of Christians, executed by the Jewish king Dhu Nuwas, eventually led to the fall of the Homerite Kingdom. In modern times, the establishment of the Jewish state resulted in the 1947 Aden riots, after which most Teimanim left the country during Operation Magic Carpet.

Conflicting geopolitical interests surfaced during the North Yemen Civil War (1962–1970). Wahhabist Saudi Arabia and other Arab monarchies supported Muhammad al-Badr, the deposed Zaydi imam of the Kingdom of Yemen. His adversary, Abdullah al-Sallal, received support from Egypt and other Arab republics. Both international backings were not based on religious sectarian affiliation. In Yemen however, President Abdullah al-Sallal (a Zaydi) sidelined his vice-president Abdurrahman al-Baidani (a Shaffi'i) for not being a member of the Zaydi sect. Shaffi'i officials of North Yemen also lobbied for "the establishment of a separate Shaffi'i state in Lower Yemen" in this period.

Contemporary Sunni-Shia rivalry

According to Lisa Wedeen, the perceived sectarian rivalry between Sunnis and Shias in the Muslim world is not the same as Yemen's sectarian rivalry between Salafists and Houthis. Not all supporters of Houthi's Ansar Allah movement are Shia, and not all Zaydis are Houthis. Although most Houthis are followers of Shia's Zaydi branch, most Shias in the world are from the Twelver branch. Yemen is geographically not in proximity of the so-called Shia Crescent. To link Hezbollah and Iran, whose subjects are overwhelmingly Twelver Shias, organically with Houthis is exploited for political purposes. Saudi Arabia emphasized an alleged military support of Iran for the Houthis during Operation Scorched Earth. The slogan of the Houthi movement is 'Death to America, death to Israel, a curse upon the Jews'. This is a trope of Iran and Hezbollah, so the Houthis seem to have no qualms about a perceived association with them.

Tribes and political movements

Tribal culture in the southern regions has virtually disappeared through policies of the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen. However, Yemen's northern part is still home to the powerful tribal confederations of Bakil and Hashid. These tribal confederations maintain their own institutions without state interference, such as prisons, courts, and armed forces. Unlike the Bakils, the Hashids adopted Salafist tenets, and during the Sa’dah War (2004–2015) sectarian tensions materialized. Yemen's Salafists attacked the Zaydi Mosque of Razih in Sa’dah and destroyed tombs of Zaydi imams across Yemen. In turn, Houthis attacked Yemen's main Salafist center of Muqbil bin Hadi al-Wadi'I during the Siege of Dammaj. Houthis also attacked the Salafist Bin Salman Mosque and threatened various Teimanim families.

Members of Hashid's elite founded the Sunni Islamist party Al-Islah and, as a counterpart, Hizb al-Haqq was founded by Zaydis with the support of Bakil's elite. Violent non-state actors Al-Qaeda, Ansar al-Sharia and Daesh, particularly active in southern cities like Mukalla, fuel sectarian tendencies with their animosity towards Yemen's Isma'ilis, Zaydis, and others. An assassination attempt in 1995 on Hosni Mubarak, executed by Yemen's Islamists, damaged the country's international reputation. The war on terror further strengthened Salafist-jihadist groups impact on Yemen's politics. The 2000 USS Cole bombing resulted in US military operations on Yemen's soil. Collateral damage caused by cruise missiles, cluster bombs, and drone attacks, deployed by the United States, compromised Yemen's sovereignty.

Ali Abdullah Saleh's reign

Ali Abdullah Saleh is a Zaydi from the Hashid's Sanhan clan and founder of the nationalist party General People's Congress. During his decades long reign as head of state, he used Sa'dah's Salafist's ideological dissemination against Zaydi's Islamic revival advocacy. In addition, the Armed Forces of Yemen used Salafists as mercenaries to fight against Houthis. Though, Ali Abdullah Saleh also used Houthis as a political counterweight to Yemen's Muslim Brotherhood. Due to the Houthis persistent opposition to the central government, Upper Yemen was economically marginalized by the state. This policy of divide and rule executed by Ali Abdullah Saleh worsened Yemen's social cohesion and nourished sectarian persuasions within Yemen's society.

Following the Arab Spring and the Yemeni Revolution, Ali Abdullah Saleh was forced to step down as president in 2012. Subsequently, a complex and violent power struggle broke out between three national alliances: (1) Ali Abdullah Saleh, his political party General People's Congress, and the Houthis; (2) Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar, supported by the political party Al-Islah; (3) Abdrabbuh Mansur Hadi, supported by the Joint Meeting Parties. According to Ibrahim Fraihat, “Yemen’s conflict has never been about sectarianism, as the Houthis were originally motivated by economic and political grievances. However, in 2014, the regional context substantially changed”. The Houthi takeover in 2014-2015 provoked a Saudi-led intervention, strengthening the sectarian dimension of the conflict. Hezbollah's Hassan Nasrallah heavily criticized the Saudi intervention, bolstering the regional Sunni-Shia geopolitical dynamic behind it.

Saudi Arabia

Sectarianism in Saudi Arabia is exemplified through the tensions with its Shi’ite population, who constitute up to 15% of the Saudi population. This includes the anti-Shi’ite policies and persecution of the Shi’ites by the Saudi government. According to Human Rights Watch, Shi’ites face marginalisation socially, politically, religiously, legally and economically, whilst facing discrimination in education and in the workplace. This history dates back to 1744, with the establishment of a coalition between the House of Saud and the Wahhabis, who equate Shi’ism with polytheism. Over the course of the twentieth century clashes and tensions unfolded between the Shi’ites and the Saudi regime, including the 1979 Qatif Uprising and the repercussions of the 1987 Makkah Incident. Though relations underwent a détente in the 1990s and the early 2000s, tensions rose again after the 2003 US-led election of Iraq (owing to a broader rise of Shi’ism in the region) and peaked during the Arab Spring. Sectarianism in Saudi Arabia has attracted widespread attention by Human Rights groups, including Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, especially after the execution of Shi'ite cleric Nimr al-Nimr in 2016, who was active in the 2011 domestic protests. Despite Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman's reforms, Shi’ites continue to face discrimination today.

Lebanon

Sectarianism in Lebanon has been formalized and legalized within state and non-state institutions and is inscribed in its constitution. Lebanon recognizes 18 different sects, mainly within Muslim and Christian worlds. The foundations of sectarianism in Lebanon date back to the mid-19th century during Ottoman rule. It was subsequently reinforced with the creation of the Republic of Lebanon in 1920 and its 1926 constitution and in the National Pact of 1943. In 1990, with the Taif Agreement, the constitution was revised but did not structurally change aspects relating to political sectarianism. The dynamic nature of sectarianism in Lebanon has prompted some historians and authors to refer to it as "the sectarian state par excellence" because it is a mixture of religious communities and their myriad sub-divisions, with a constitutional and political order to match. Yet, the reality on the ground has been more complex than such a conclusion, because as Nadya Sbaiti has shown in her research, in the aftermath of the First World War, the “need of shaping a collective future that paralleled shifting conceptions of the newly territorialized nation-state of Lebanon” was clearly present. “Over the course of the Mandate, educational practitioners and the wide range of schools that proliferated helped shape the epistemological infrastructure en route to creating this entity. By ‘epistemological infrastructure’, one means the cast array of ideas that become validated as truths and convincing explanations.” In other words, contrary to the colonial sectarian education system, “students, parents, and teachers created educational content through curricula, and educational practices so as to produce new ‘communities of knowledge’. These communities of knowledge, connected as they were by worlds of ideas and networks of knowledge, often transcended confessional, sociopolitical, and even at times regional subjectivities.” Some of these schools such as the "Ahliyya National School for Girls" would even go as far as to promote an anti-colonial stance among students to increase popular resistance towards French Mandate policies at the time. This perspective therefore also uncovers the underlying factors at work within these historical events and confirms that such happenings were not inevitable but simply one of many paths for possible outcomes. In a more recent development, the sectarian political system in Lebanon was questioned, as 2019-uprisings prompted "calls to dismantle the system were both a culmination of the growth of multiple activist movements over the past decades—including the intersection of antisectarian, feminist, environmentalist, and queer rights strands—and an echo of earlier movements on the left."