A magnet levitating above a high-temperature superconductor, cooled with liquid nitrogen. Persistent electric current flows on the surface of the superconductor, acting to exclude the magnetic field of the magnet (Faraday's law of induction). This current effectively forms an electromagnet that repels the magnet.

Video of a Meissner effect in a high-temperature superconductor (black pellet) with a NdFeB magnet (metallic)

A high-temperature superconductor levitating above a magnet

Superconductivity is a phenomenon of exactly zero electrical resistance and expulsion of magnetic flux fields occurring in certain materials, called superconductors, when cooled below a characteristic critical temperature. It was discovered by Dutch physicist Heike Kamerlingh Onnes on April 8, 1911, in Leiden. Like ferromagnetism and atomic spectral lines, superconductivity is a quantum mechanical phenomenon. It is characterized by the Meissner effect, the complete ejection of magnetic field lines from the interior of the superconductor during its transitions into the superconducting state. The occurrence of the Meissner effect indicates that superconductivity cannot be understood simply as the idealization of perfect conductivity in classical physics.

The electrical resistance of a metallic conductor decreases gradually as temperature is lowered. In ordinary conductors, such as copper or silver, this decrease is limited by impurities and other defects. Even near absolute zero, a real sample of a normal conductor shows some resistance. In a superconductor, the resistance drops abruptly to zero when the material is cooled below its critical temperature. An electric current through a loop of superconducting wire can persist indefinitely with no power source.[1][2][3][4]

In 1986, it was discovered that some cuprate-perovskite ceramic materials have a critical temperature above 90 K (−183 °C).[5] Such a high transition temperature is theoretically impossible for a conventional superconductor, leading the materials to be termed high-temperature superconductors. The cheaply-available coolant liquid nitrogen boils at 77 K, and thus superconduction at higher temperatures than this facilitates many experiments and applications that are less practical at lower temperatures.

Classification

There are many criteria by which superconductors are classified. The most common are:Response to a magnetic field

A superconductor can be Type I, meaning it has a single critical field, above which all superconductivity is lost and below which the magnetic field is completely expelled from the superconductor; or Type II, meaning it has two critical fields, between which it allows partial penetration of the magnetic field through isolated points. These points are called vortices. Furthermore, in multicomponent superconductors it is possible to have combination of the two behaviours. In that case the superconductor is of Type-1.5.By theory of operation

It is conventional if it can be explained by the BCS theory or its derivatives, or unconventional, otherwise.[6]By critical temperature

A superconductor is generally considered high-temperature if it reaches a superconducting state when cooled using liquid nitrogen – that is, at only Tc > 77 K) – or low-temperature if more aggressive cooling techniques are required to reach its critical temperature.By material

Superconductor material classes include chemical elements (e.g. mercury or lead), alloys (such as niobium-titanium, germanium-niobium, and niobium nitride), ceramics (YBCO and magnesium diboride), superconducting pnictides (like fluorine-doped LaOFeAs) or organic superconductors (fullerenes and carbon nanotubes; though perhaps these examples should be included among the chemical elements, as they are composed entirely of carbon).Elementary properties of superconductors

Most of the physical properties of superconductors vary from material to material, such as the heat capacity and the critical temperature, critical field, and critical current density at which superconductivity is destroyed.On the other hand, there is a class of properties that are independent of the underlying material. For instance, all superconductors have exactly zero resistivity to low applied currents when there is no magnetic field present or if the applied field does not exceed a critical value. The existence of these "universal" properties implies that superconductivity is a thermodynamic phase, and thus possesses certain distinguishing properties which are largely independent of microscopic details.

Zero electrical DC resistance

Cross section of a preform superconductor rod from abandoned Texas Superconducting Super Collider (SSC).

The simplest method to measure the electrical resistance of a sample of some material is to place it in an electrical circuit in series with a current source I and measure the resulting voltage V across the sample. The resistance of the sample is given by Ohm's law as R = V / I. If the voltage is zero, this means that the resistance is zero.

Superconductors are also able to maintain a current with no applied voltage whatsoever, a property exploited in superconducting electromagnets such as those found in MRI machines. Experiments have demonstrated that currents in superconducting coils can persist for years without any measurable degradation. Experimental evidence points to a current lifetime of at least 100,000 years. Theoretical estimates for the lifetime of a persistent current can exceed the estimated lifetime of the universe, depending on the wire geometry and the temperature.[3] In practice, currents injected in superconducting coils have persisted for more than 22 years in superconducting gravimeters.[7][8] In such instruments, the measurement principle is based on the monitoring of the levitation of a superconducting niobium sphere of mass 4 grams.

In a normal conductor, an electric current may be visualized as a fluid of electrons moving across a heavy ionic lattice. The electrons are constantly colliding with the ions in the lattice, and during each collision some of the energy carried by the current is absorbed by the lattice and converted into heat, which is essentially the vibrational kinetic energy of the lattice ions. As a result, the energy carried by the current is constantly being dissipated. This is the phenomenon of electrical resistance and Joule heating.

The situation is different in a superconductor. In a conventional superconductor, the electronic fluid cannot be resolved into individual electrons. Instead, it consists of bound pairs of electrons known as Cooper pairs. This pairing is caused by an attractive force between electrons from the exchange of phonons. Due to quantum mechanics, the energy spectrum of this Cooper pair fluid possesses an energy gap, meaning there is a minimum amount of energy ΔE that must be supplied in order to excite the fluid. Therefore, if ΔE is larger than the thermal energy of the lattice, given by kT, where k is Boltzmann's constant and T is the temperature, the fluid will not be scattered by the lattice. The Cooper pair fluid is thus a superfluid, meaning it can flow without energy dissipation.

In a class of superconductors known as type II superconductors, including all known high-temperature superconductors, an extremely low but nonzero resistivity appears at temperatures not too far below the nominal superconducting transition when an electric current is applied in conjunction with a strong magnetic field, which may be caused by the electric current. This is due to the motion of magnetic vortices in the electronic superfluid, which dissipates some of the energy carried by the current. If the current is sufficiently small, the vortices are stationary, and the resistivity vanishes. The resistance due to this effect is tiny compared with that of non-superconducting materials, but must be taken into account in sensitive experiments. However, as the temperature decreases far enough below the nominal superconducting transition, these vortices can become frozen into a disordered but stationary phase known as a "vortex glass". Below this vortex glass transition temperature, the resistance of the material becomes truly zero.

Superconducting phase transition

Behavior of heat capacity (cv, blue) and resistivity (ρ, green) at the superconducting phase transition

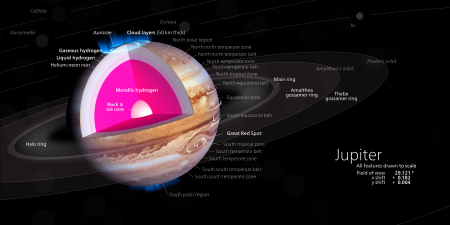

In superconducting materials, the characteristics of superconductivity appear when the temperature T is lowered below a critical temperature Tc. The value of this critical temperature varies from material to material. Conventional superconductors usually have critical temperatures ranging from around 20 K to less than 1 K. Solid mercury, for example, has a critical temperature of 4.2 K. As of 2009, the highest critical temperature found for a conventional superconductor is 39 K for magnesium diboride (MgB2),[9][10] although this material displays enough exotic properties that there is some doubt about classifying it as a "conventional" superconductor.[11] Cuprate superconductors can have much higher critical temperatures: YBa2Cu3O7, one of the first cuprate superconductors to be discovered, has a critical temperature of 92 K, and mercury-based cuprates have been found with critical temperatures in excess of 130 K. The explanation for these high critical temperatures remains unknown. Electron pairing due to phonon exchanges explains superconductivity in conventional superconductors, but it does not explain superconductivity in the newer superconductors that have a very high critical temperature.

Similarly, at a fixed temperature below the critical temperature, superconducting materials cease to superconduct when an external magnetic field is applied which is greater than the critical magnetic field. This is because the Gibbs free energy of the superconducting phase increases quadratically with the magnetic field while the free energy of the normal phase is roughly independent of the magnetic field. If the material superconducts in the absence of a field, then the superconducting phase free energy is lower than that of the normal phase and so for some finite value of the magnetic field (proportional to the square root of the difference of the free energies at zero magnetic field) the two free energies will be equal and a phase transition to the normal phase will occur. More generally, a higher temperature and a stronger magnetic field lead to a smaller fraction of electrons that are superconducting and consequently to a longer London penetration depth of external magnetic fields and currents. The penetration depth becomes infinite at the phase transition.

The onset of superconductivity is accompanied by abrupt changes in various physical properties, which is the hallmark of a phase transition. For example, the electronic heat capacity is proportional to the temperature in the normal (non-superconducting) regime. At the superconducting transition, it suffers a discontinuous jump and thereafter ceases to be linear. At low temperatures, it varies instead as e−α/T for some constant, α. This exponential behavior is one of the pieces of evidence for the existence of the energy gap.

The order of the superconducting phase transition was long a matter of debate. Experiments indicate that the transition is second-order, meaning there is no latent heat. However, in the presence of an external magnetic field there is latent heat, because the superconducting phase has a lower entropy below the critical temperature than the normal phase. It has been experimentally demonstrated[12] that, as a consequence, when the magnetic field is increased beyond the critical field, the resulting phase transition leads to a decrease in the temperature of the superconducting material.

Calculations in the 1970s suggested that it may actually be weakly first-order due to the effect of long-range fluctuations in the electromagnetic field. In the 1980s it was shown theoretically with the help of a disorder field theory, in which the vortex lines of the superconductor play a major role, that the transition is of second order within the type II regime and of first order (i.e., latent heat) within the type I regime, and that the two regions are separated by a tricritical point.[13] The results were strongly supported by Monte Carlo computer simulations.[14]

Meissner effect

When a superconductor is placed in a weak external magnetic field H, and cooled below its transition temperature, the magnetic field is ejected. The Meissner effect does not cause the field to be completely ejected but instead the field penetrates the superconductor but only to a very small distance, characterized by a parameter λ, called the London penetration depth, decaying exponentially to zero within the bulk of the material. The Meissner effect is a defining characteristic of superconductivity. For most superconductors, the London penetration depth is on the order of 100 nm.The Meissner effect is sometimes confused with the kind of diamagnetism one would expect in a perfect electrical conductor: according to Lenz's law, when a changing magnetic field is applied to a conductor, it will induce an electric current in the conductor that creates an opposing magnetic field. In a perfect conductor, an arbitrarily large current can be induced, and the resulting magnetic field exactly cancels the applied field.

The Meissner effect is distinct from this—it is the spontaneous expulsion which occurs during transition to superconductivity. Suppose we have a material in its normal state, containing a constant internal magnetic field. When the material is cooled below the critical temperature, we would observe the abrupt expulsion of the internal magnetic field, which we would not expect based on Lenz's law.

The Meissner effect was given a phenomenological explanation by the brothers Fritz and Heinz London, who showed that the electromagnetic free energy in a superconductor is minimized provided

This equation, which is known as the London equation, predicts that the magnetic field in a superconductor decays exponentially from whatever value it possesses at the surface.

A superconductor with little or no magnetic field within it is said to be in the Meissner state. The Meissner state breaks down when the applied magnetic field is too large. Superconductors can be divided into two classes according to how this breakdown occurs. In Type I superconductors, superconductivity is abruptly destroyed when the strength of the applied field rises above a critical value Hc. Depending on the geometry of the sample, one may obtain an intermediate state[15] consisting of a baroque pattern[16] of regions of normal material carrying a magnetic field mixed with regions of superconducting material containing no field. In Type II superconductors, raising the applied field past a critical value Hc1 leads to a mixed state (also known as the vortex state) in which an increasing amount of magnetic flux penetrates the material, but there remains no resistance to the flow of electric current as long as the current is not too large. At a second critical field strength Hc2, superconductivity is destroyed. The mixed state is actually caused by vortices in the electronic superfluid, sometimes called fluxons because the flux carried by these vortices is quantized. Most pure elemental superconductors, except niobium and carbon nanotubes, are Type I, while almost all impure and compound superconductors are Type II.

London moment

Conversely, a spinning superconductor generates a magnetic field, precisely aligned with the spin axis. The effect, the London moment, was put to good use in Gravity Probe B. This experiment measured the magnetic fields of four superconducting gyroscopes to determine their spin axes. This was critical to the experiment since it is one of the few ways to accurately determine the spin axis of an otherwise featureless sphere.History of superconductivity

Heike Kamerlingh Onnes (right), the discoverer of superconductivity. Paul Ehrenfest, Hendrik Lorentz, Niels Bohr stand to his left.

Superconductivity was discovered on April 8, 1911 by Heike Kamerlingh Onnes, who was studying the resistance of solid mercury at cryogenic temperatures using the recently produced liquid helium as a refrigerant. At the temperature of 4.2 K, he observed that the resistance abruptly disappeared.[17] In the same experiment, he also observed the superfluid transition of helium at 2.2 K, without recognizing its significance. The precise date and circumstances of the discovery were only reconstructed a century later, when Onnes's notebook was found.[18] In subsequent decades, superconductivity was observed in several other materials. In 1913, lead was found to superconduct at 7 K, and in 1941 niobium nitride was found to superconduct at 16 K.

Great efforts have been devoted to finding out how and why superconductivity works; the important step occurred in 1933, when Meissner and Ochsenfeld discovered that superconductors expelled applied magnetic fields, a phenomenon which has come to be known as the Meissner effect.[19] In 1935, Fritz and Heinz London showed that the Meissner effect was a consequence of the minimization of the electromagnetic free energy carried by superconducting current.[20]

London theory

The first phenomenological theory of superconductivity was London theory. It was put forward by the brothers Fritz and Heinz London in 1935, shortly after the discovery that magnetic fields are expelled from superconductors. A major triumph of the equations of this theory is their ability to explain the Meissner effect,[19] wherein a material exponentially expels all internal magnetic fields as it crosses the superconducting threshold. By using the London equation, one can obtain the dependence of the magnetic field inside the superconductor on the distance to the surface.[21]There are two London equations:

Conventional theories (1950s)

During the 1950s, theoretical condensed matter physicists arrived at an understanding of "conventional" superconductivity, through a pair of remarkable and important theories: the phenomenological Ginzburg-Landau theory (1950) and the microscopic BCS theory (1957).[22][23]In 1950, the phenomenological Ginzburg-Landau theory of superconductivity was devised by Landau and Ginzburg.[24] This theory, which combined Landau's theory of second-order phase transitions with a Schrödinger-like wave equation, had great success in explaining the macroscopic properties of superconductors. In particular, Abrikosov showed that Ginzburg-Landau theory predicts the division of superconductors into the two categories now referred to as Type I and Type II. Abrikosov and Ginzburg were awarded the 2003 Nobel Prize for their work (Landau had received the 1962 Nobel Prize for other work, and died in 1968). The four-dimensional extension of the Ginzburg-Landau theory, the Coleman-Weinberg model, is important in quantum field theory and cosmology.

Also in 1950, Maxwell and Reynolds et al. found that the critical temperature of a superconductor depends on the isotopic mass of the constituent element.[25][26] This important discovery pointed to the electron-phonon interaction as the microscopic mechanism responsible for superconductivity.

The complete microscopic theory of superconductivity was finally proposed in 1957 by Bardeen, Cooper and Schrieffer.[23] This BCS theory explained the superconducting current as a superfluid of Cooper pairs, pairs of electrons interacting through the exchange of phonons. For this work, the authors were awarded the Nobel Prize in 1972.

The BCS theory was set on a firmer footing in 1958, when N. N. Bogolyubov showed that the BCS wavefunction, which had originally been derived from a variational argument, could be obtained using a canonical transformation of the electronic Hamiltonian.[27] In 1959, Lev Gor'kov showed that the BCS theory reduced to the Ginzburg-Landau theory close to the critical temperature.[28][29]

Generalizations of BCS theory for conventional superconductors form the basis for understanding of the phenomenon of superfluidity, because they fall into the lambda transition universality class. The extent to which such generalizations can be applied to unconventional superconductors is still controversial.

Further history

The first practical application of superconductivity was developed in 1954 with Dudley Allen Buck's invention of the cryotron.[30] Two superconductors with greatly different values of critical magnetic field are combined to produce a fast, simple switch for computer elements.Soon after discovering superconductivity in 1911, Kamerlingh Onnes attempted to make an electromagnet with superconducting windings but found that relatively low magnetic fields destroyed superconductivity in the materials he investigated. Much later, in 1955, G.B. Yntema [31] succeeded in constructing a small 0.7-tesla iron-core electromagnet with superconducting niobium wire windings. Then, in 1961, J.E. Kunzler, E. Buehler, F.S.L. Hsu, and J.H. Wernick [32] made the startling discovery that, at 4.2 kelvin, a compound consisting of three parts niobium and one part tin, was capable of supporting a current density of more than 100,000 amperes per square centimeter in a magnetic field of 8.8 tesla. Despite being brittle and difficult to fabricate, niobium-tin has since proved extremely useful in supermagnets generating magnetic fields as high as 20 tesla. In 1962 T.G. Berlincourt and R.R. Hake [33][34] discovered that alloys of niobium and titanium are suitable for applications up to 10 tesla. Promptly thereafter, commercial production of niobium-titanium supermagnet wire commenced at Westinghouse Electric Corporation and at Wah Chang Corporation. Although niobium-titanium boasts less-impressive superconducting properties than those of niobium-tin, niobium-titanium has, nevertheless, become the most widely used “workhorse” supermagnet material, in large measure a consequence of its very-high ductility and ease of fabrication. However, both niobium-tin and niobium-titanium find wide application in MRI medical imagers, bending and focusing magnets for enormous high-energy-particle accelerators, and a host of other applications. Conectus, a European superconductivity consortium, estimated that in 2014, global economic activity for which superconductivity was indispensable amounted to about five billion euros, with MRI systems accounting for about 80% of that total.

In 1962, Josephson made the important theoretical prediction that a supercurrent can flow between two pieces of superconductor separated by a thin layer of insulator.[35] This phenomenon, now called the Josephson effect, is exploited by superconducting devices such as SQUIDs. It is used in the most accurate available measurements of the magnetic flux quantum Φ0 = h/(2e), where h is the Planck constant. Coupled with the quantum Hall resistivity, this leads to a precise measurement of the Planck constant. Josephson was awarded the Nobel Prize for this work in 1973.

In 2008, it was proposed that the same mechanism that produces superconductivity could produce a superinsulator state in some materials, with almost infinite electrical resistance.[36]

High-temperature superconductivity

Timeline of superconducting materials

Until 1986, physicists had believed that BCS theory forbade superconductivity at temperatures above about 30 K. In that year, Bednorz and Müller discovered superconductivity in a lanthanum-based cuprate perovskite material, which had a transition temperature of 35 K (Nobel Prize in Physics, 1987).[5] It was soon found that replacing the lanthanum with yttrium (i.e., making YBCO) raised the critical temperature to 92 K.[37]

This temperature jump is particularly significant, since it allows liquid nitrogen as a refrigerant, replacing liquid helium.[37] This can be important commercially because liquid nitrogen can be produced relatively cheaply, even on-site. Also, the higher temperatures help avoid some of the problems that arise at liquid helium temperatures, such as the formation of plugs of frozen air that can block cryogenic lines and cause unanticipated and potentially hazardous pressure buildup.[38][39]

Many other cuprate superconductors have since been discovered, and the theory of superconductivity in these materials is one of the major outstanding challenges of theoretical condensed matter physics.[40] There are currently two main hypotheses – the resonating-valence-bond theory, and spin fluctuation which has the most support in the research community.[41] The second hypothesis proposed that electron pairing in high-temperature superconductors is mediated by short-range spin waves known as paramagnons.[42][43][dubious ]

Since about 1993, the highest-temperature superconductor has been a ceramic material consisting of mercury, barium, calcium, copper and oxygen (HgBa2Ca2Cu3O8+δ) with Tc = 133–138 K.[44][45] The latter experiment (138 K) still awaits experimental confirmation, however.

In February 2008, an iron-based family of high-temperature superconductors was discovered.[46][47] Hideo Hosono, of the Tokyo Institute of Technology, and colleagues found lanthanum oxygen fluorine iron arsenide (LaO1−xFxFeAs), an oxypnictide that superconducts below 26 K. Replacing the lanthanum in LaO1−xFxFeAs with samarium leads to superconductors that work at 55 K.[48]

In May 2014, hydrogen sulfide (H

2S) was predicted to be a high-temperature superconductor with a transition temperature of 80 K at 160 gigapascals of pressure.[49] In 2015, H

2S has been observed to exhibit superconductivity at below 203 K but at extremely high pressures — around 150 gigapascals.[50]

Applications

Play media

Video of superconducting levitation of YBCO

Superconducting magnets are some of the most powerful electromagnets known. They are used in MRI/NMR machines, mass spectrometers, the beam-steering magnets used in particle accelerators and plasma confining magnets in some tokamaks. They can also be used for magnetic separation, where weakly magnetic particles are extracted from a background of less or non-magnetic particles, as in the pigment industries.

In the 1950s and 1960s, superconductors were used to build experimental digital computers using cryotron switches. More recently, superconductors have been used to make digital circuits based on rapid single flux quantum technology and RF and microwave filters for mobile phone base stations.

Superconductors are used to build Josephson junctions which are the building blocks of SQUIDs (superconducting quantum interference devices), the most sensitive magnetometers known. SQUIDs are used in scanning SQUID microscopes and magnetoencephalography. Series of Josephson devices are used to realize the SI volt. Depending on the particular mode of operation, a superconductor-insulator-superconductor Josephson junction can be used as a photon detector or as a mixer. The large resistance change at the transition from the normal- to the superconducting state is used to build thermometers in cryogenic micro-calorimeter photon detectors. The same effect is used in ultrasensitive bolometers made from superconducting materials.

Other early markets are arising where the relative efficiency, size and weight advantages of devices based on high-temperature superconductivity outweigh the additional costs involved. For example, in wind turbines the lower weight and volume of superconducting generators could lead to savings in construction and tower costs, offsetting the higher costs for the generator and lowering the total LCOE.[51]

Promising future applications include high-performance smart grid, electric power transmission, transformers, power storage devices, electric motors (e.g. for vehicle propulsion, as in vactrains or maglev trains), magnetic levitation devices, fault current limiters, enhancing spintronic devices with superconducting materials,[52] and superconducting magnetic refrigeration. However, superconductivity is sensitive to moving magnetic fields so applications that use alternating current (e.g. transformers) will be more difficult to develop than those that rely upon direct current. Compared to traditional power lines superconducting transmission lines are more efficient and require only a fraction of the space, which would not only lead to a better environmental performance but could also improve public acceptance for expansion of the electric grid.[53]

Nobel Prizes for superconductivity

- Heike Kamerlingh Onnes (1913), "for his investigations on the properties of matter at low temperatures which led, inter alia, to the production of liquid helium"

- John Bardeen, Leon N. Cooper, and J. Robert Schrieffer (1972), "for their jointly developed theory of superconductivity, usually called the BCS-theory"

- Leo Esaki, Ivar Giaever, and Brian D. Josephson (1973), "for their experimental discoveries regarding tunneling phenomena in semiconductors and superconductors, respectively," and "for his theoretical predictions of the properties of a supercurrent through a tunnel barrier, in particular those phenomena which are generally known as the Josephson effects"

- Georg Bednorz and K. Alex Müller (1987), "for their important break-through in the discovery of superconductivity in ceramic materials"

- Alexei A. Abrikosov, Vitaly L. Ginzburg, and Anthony J. Leggett (2003), "for pioneering contributions to the theory of superconductors and superfluids"[54]

- Michael Kosterlitz, Duncan Haldane, David J. Thouless (2016)