Programs officially supplied by companies can be considered

malware if they secretly act against the interests of the computer user.

For example, at one point Sony music Compact discs silently installed a rootkit

on purchasers' computers with the intention of preventing illicit

copying; but which also reported on users' listening habits, and

unintentionally created extra security vulnerabilities.

One strategy for protecting against malware is to prevent the malware software from gaining access to the target computer. For this reason, antivirus software, firewalls and other strategies are used to help protect against the introduction of malware, in addition to checking for the presence of malware and malicious activity and recovering from attacks.

One strategy for protecting against malware is to prevent the malware software from gaining access to the target computer. For this reason, antivirus software, firewalls and other strategies are used to help protect against the introduction of malware, in addition to checking for the presence of malware and malicious activity and recovering from attacks.

Purposes

Many early infectious programs, including the first Internet Worm, were written as experiments or pranks. Today, malware is used by both black hat hackers and governments, to steal personal, financial, or business information.

Malware is sometimes used broadly against government or corporate websites to gather guarded information,

or to disrupt their operation in general. However, malware can be used

against individuals to gain information such as personal identification

numbers or details, bank or credit card numbers, and passwords.

Since the rise of widespread broadband Internet access, malicious software has more frequently been designed for profit. Since 2003, the majority of widespread viruses and worms have been designed to take control of users' computers for illicit purposes. Infected "zombie computers" can be used to send email spam, to host contraband data such as child pornography, or to engage in distributed denial-of-service attacks as a form of extortion.

Programs designed to monitor users' web browsing, display unsolicited advertisements, or redirect affiliate marketing revenues are called spyware.

Spyware programs do not spread like viruses; instead they are generally

installed by exploiting security holes. They can also be hidden and

packaged together with unrelated user-installed software. The Sony BMG rootkit

was intended to preventing illicit copying; but also reported on users'

listening habits, and unintentionally created extra security

vulnerabilities.

Ransomware affects an infected computer system in some way, and

demands payment to bring it back to its normal state. For example,

programs such as CryptoLocker encrypt files securely, and only decrypt them on payment of a substantial sum of money.

Some malware is used to generate money by click fraud,

making it appear that the computer user has clicked an advertising link

on a site, generating a payment from the advertiser. It was estimated

in 2012 that about 60 to 70% of all active malware used some kind of

click fraud, and 22% of all ad-clicks were fraudulent.

In addition to criminal money-making, malware can be used for sabotage, often for political motives. Stuxnet,

for example, was designed to disrupt very specific industrial

equipment. There have been politically motivated attacks that have

spread over and shut down large computer networks, including massive

deletion of files and corruption of master boot records,

described as "computer killing". Such attacks were made on Sony

Pictures Entertainment (25 November 2014, using malware known as Shamoon or W32.Disttrack) and Saudi Aramco (August 2012).

Infectious malware

The best-known types of malware, viruses and worms, are known for the

manner in which they spread, rather than any specific types of

behavior. A computer virus is software that embeds itself in some other executable

software (including the operating system itself) on the target system

without the user's knowledge and consent and when it is run, the virus

is spread to other executables. On the other hand, a worm is a stand-alone malware software that actively transmits itself over a network

to infect other computers. These definitions lead to the observation

that a virus requires the user to run an infected software or operating

system for the virus to spread, whereas a worm spreads itself.

Concealment

These categories are not mutually exclusive, so malware may use multiple techniques. This section only applies to malware designed to operate undetected, not sabotage and ransomware.

Viruses

A computer virus is software usually hidden within another seemingly

innocuous program that can produce copies of itself and insert them into

other programs or files, and that usually performs a harmful action

(such as destroying data). An example of this is a PE infection, a technique, usually used to spread malware, that inserts extra data or executable code into PE files.

Screen-locking ransomware

Lock-screens, or screen lockers is a type of “cyber police”

ransomware that blocks screens on Windows or Android devices with a

false accusation in harvesting illegal content, trying to scare the

victims into paying up a fee.

Jisut and SLocker impact Android devices more than other lock-screens,

with Jisut making up nearly 60 percent of all Android ransomware

detections.

Trojan horses

A Trojan horse is a harmful program that misrepresents itself to

masquerade as a regular, benign program or utility in order to persuade a

victim to install it. A Trojan horse usually carries a hidden

destructive function that is activated when the application is started.

The term is derived from the Ancient Greek story of the Trojan horse used to invade the city of Troy by stealth.

Trojan horses are generally spread by some form of social engineering,

for example, where a user is duped into executing an e-mail attachment

disguised to be unsuspicious, (e.g., a routine form to be filled in), or

by drive-by download. Although their payload can be anything, many modern forms act as a backdoor, contacting a controller which can then have unauthorized access to the affected computer.

While Trojan horses and backdoors are not easily detectable by

themselves, computers may appear to run slower due to heavy processor or

network usage.

Unlike computer viruses and worms, Trojan horses generally do not

attempt to inject themselves into other files or otherwise propagate

themselves.

In spring 2017 Mac users were hit by the new version of Proton Remote Access Trojan (RAT)

trained to extract password data from various sources, such as browser

auto-fill data, the Mac-OS keychain, and password vaults.

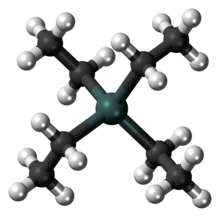

Rootkits

Once malicious software is installed on a system, it is essential

that it stays concealed, to avoid detection. Software packages known as rootkits

allow this concealment, by modifying the host's operating system so

that the malware is hidden from the user. Rootkits can prevent a harmful

process from being visible in the system's list of processes, or keep its files from being read.

Some types of harmful software contain routines to evade

identification and/or removal attempts, not merely to hide themselves.

An early example of this behavior is recorded in the Jargon File tale of a pair of programs infesting a Xerox CP-V time sharing system:

- Each ghost-job would detect the fact that the other had been killed, and would start a new copy of the recently stopped program within a few milliseconds. The only way to kill both ghosts was to kill them simultaneously (very difficult) or to deliberately crash the system.

Backdoors

A backdoor is a method of bypassing normal authentication

procedures, usually over a connection to a network such as the

Internet. Once a system has been compromised, one or more backdoors may

be installed in order to allow access in the future, invisibly to the user.

The idea has often been suggested that computer manufacturers

preinstall backdoors on their systems to provide technical support for

customers, but this has never been reliably verified. It was reported in

2014 that US government agencies had been diverting computers purchased

by those considered "targets" to secret workshops where software or

hardware permitting remote access by the agency was installed,

considered to be among the most productive operations to obtain access

to networks around the world. Backdoors may be installed by Trojan horses, worms, implants, or other methods.

Evasion

Since

the beginning of 2015, a sizable portion of malware utilizes a

combination of many techniques designed to avoid detection and analysis.

- The most common evasion technique is when the malware evades analysis and detection by fingerprinting the environment when executed.

- The second most common evasion technique is confusing automated tools' detection methods. This allows malware to avoid detection by technologies such as signature-based antivirus software by changing the server used by the malware.

- The third most common evasion technique is timing-based evasion. This is when malware runs at certain times or following certain actions taken by the user, so it executes during certain vulnerable periods, such as during the boot process, while remaining dormant the rest of the time.

- The fourth most common evasion technique is done by obfuscating internal data so that automated tools do not detect the malware.

- An increasingly common technique is adware that uses stolen certificates to disable anti-malware and virus protection; technical remedies are available to deal with the adware.

Nowadays, one of the most sophisticated and stealthy ways of evasion is to use information hiding techniques, namely stegomalware. A survey on stegomalware was published by Cabaj et al. in 2018.

Vulnerability

- In this context, and throughout, what is called the "system" under attack may be anything from a single application, through a complete computer and operating system, to a large network.

- Various factors make a system more vulnerable to malware:

Security defects in software

Malware exploits security defects (security bugs or vulnerabilities)

in the design of the operating system, in applications (such as

browsers, e.g. older versions of Microsoft Internet Explorer supported

by Windows XP), or in vulnerable versions of browser plugins such as Adobe Flash Player, Adobe Acrobat or Reader, or Java SE. Sometimes even installing new versions of such plugins does not automatically uninstall old versions. Security advisories from plug-in providers announce security-related updates. Common vulnerabilities are assigned CVE IDs and listed in the US National Vulnerability Database. Secunia PSI

is an example of software, free for personal use, that will check a PC

for vulnerable out-of-date software, and attempt to update it.

Malware authors target bugs, or loopholes, to exploit. A common method is exploitation of a buffer overrun

vulnerability, where software designed to store data in a specified

region of memory does not prevent more data than the buffer can

accommodate being supplied. Malware may provide data that overflows the

buffer, with malicious executable code or data after the end; when this payload is accessed it does what the attacker, not the legitimate software, determines.

Insecure design or user error

Early PCs had to be booted from floppy disks. When built-in hard drives became common, the operating system was normally started from them, but it was possible to boot from another boot device if available, such as a floppy disk, CD-ROM,

DVD-ROM, USB flash drive or network. It was common to configure the

computer to boot from one of these devices when available. Normally none

would be available; the user would intentionally insert, say, a CD into

the optical drive to boot the computer in some special way, for

example, to install an operating system. Even without booting, computers

can be configured to execute software on some media as soon as they

become available, e.g. to autorun a CD or USB device when inserted.

Malware distributors would trick the user into booting or running

from an infected device or medium. For example, a virus could make an

infected computer add autorunnable code to any USB stick plugged into

it. Anyone who then attached the stick to another computer set to

autorun from USB would in turn become infected, and also pass on the

infection in the same way.

More generally, any device that plugs into a USB port - even lights,

fans, speakers, toys, or peripherals such as a digital microscope - can

be used to spread malware. Devices can be infected during manufacturing

or supply if quality control is inadequate.

This form of infection can largely be avoided by setting up

computers by default to boot from the internal hard drive, if available,

and not to autorun from devices. Intentional booting from another device is always possible by pressing certain keys during boot.

Older email software would automatically open HTML email containing potentially malicious JavaScript code. Users may also execute disguised malicious email attachments.

Over-privileged users and over-privileged code

In computing, privilege

refers to how much a user or program is allowed to modify a system. In

poorly designed computer systems, both users and programs can be

assigned more privileges than they should be, and malware can take

advantage of this. The two ways that malware does this is through

overprivileged users and overprivileged code.

Some systems allow all users to modify their internal structures, and such users today would be considered over-privileged

users. This was the standard operating procedure for early

microcomputer and home computer systems, where there was no distinction

between an administrator or root, and a regular user of the system. In some systems, non-administrator

users are over-privileged by design, in the sense that they are allowed

to modify internal structures of the system. In some environments,

users are over-privileged because they have been inappropriately granted

administrator or equivalent status.

Some systems allow code executed by a user to access all rights

of that user, which is known as over-privileged code. This was also

standard operating procedure for early microcomputer and home computer

systems. Malware, running as over-privileged code, can use this

privilege to subvert the system. Almost all currently popular operating

systems, and also many scripting applications allow code too many privileges, usually in the sense that when a user executes code, the system allows that code all rights of that user. This makes users vulnerable to malware in the form of e-mail attachments, which may or may not be disguised.

Use of the same operating system

- Homogeneity can be a vulnerability. For example, when all computers in a network run the same operating system, upon exploiting one, one worm can exploit them all: In particular, Microsoft Windows or Mac OS X have such a large share of the market that an exploited vulnerability concentrating on either operating system could subvert a large number of systems. Introducing diversity purely for the sake of robustness, such as adding Linux computers, could increase short-term costs for training and maintenance. However, as long as all the nodes are not part of the same directory service for authentication, having a few diverse nodes could deter total shutdown of the network and allow those nodes to help with recovery of the infected nodes. Such separate, functional redundancy could avoid the cost of a total shutdown, at the cost of increased complexity and reduced usability in terms of single sign-on authentication.

Anti-malware strategies

As malware attacks become more frequent, attention has begun to shift from viruses

and spyware protection, to malware protection, and programs that have

been specifically developed to combat malware. (Other preventive and

recovery measures, such as backup and recovery methods, are mentioned in

the computer virus article).

Anti-virus and anti-malware software

A specific component of anti-virus

and anti-malware software, commonly referred to as an on-access or

real-time scanner, hooks deep into the operating system's core or kernel

and functions in a manner similar to how certain malware itself would

attempt to operate, though with the user's informed permission for

protecting the system. Any time the operating system accesses a file,

the on-access scanner checks if the file is a 'legitimate' file or not.

If the file is identified as malware by the scanner, the access

operation will be stopped, the file will be dealt with by the scanner in

a pre-defined way (how the anti-virus program was configured

during/post installation), and the user will be notified.

This may have a considerable performance impact on the operating

system, though the degree of impact is dependent on how well the scanner

was programmed. The goal is to stop any operations the malware may

attempt on the system before they occur, including activities which

might exploit bugs or trigger unexpected operating system behavior.

Anti-malware programs can combat malware in two ways:

- They can provide real time protection against the installation of malware software on a computer. This type of malware protection works the same way as that of antivirus protection in that the anti-malware software scans all incoming network data for malware and blocks any threats it comes across.

- Anti-malware software programs can be used solely for detection and removal of malware software that has already been installed onto a computer. This type of anti-malware software scans the contents of the Windows registry, operating system files, and installed programs on a computer and will provide a list of any threats found, allowing the user to choose which files to delete or keep, or to compare this list to a list of known malware components, removing files that match.

Real-time protection from malware works identically to real-time

antivirus protection: the software scans disk files at download time,

and blocks the activity of components known to represent malware. In

some cases, it may also intercept attempts to install start-up items or

to modify browser settings. Because many malware components are

installed as a result of browser exploits

or user error, using security software (some of which are anti-malware,

though many are not) to "sandbox" browsers (essentially isolate the

browser from the computer and hence any malware induced change) can also

be effective in helping to restrict any damage done.

Examples of Microsoft Windows antivirus and anti-malware software include the optional Microsoft Security Essentials (for Windows XP, Vista, and Windows 7) for real-time protection, the Windows Malicious Software Removal Tool (now included with Windows (Security) Updates on "Patch Tuesday", the second Tuesday of each month), and Windows Defender (an optional download in the case of Windows XP, incorporating MSE functionality in the case of Windows 8 and later).

Additionally, several capable antivirus software programs are available

for free download from the Internet (usually restricted to

non-commercial use). Tests found some free programs to be competitive with commercial ones. Microsoft's System File Checker can be used to check for and repair corrupted system files.

Some viruses disable System Restore and other important Windows tools such as Task Manager and Command Prompt. Many such viruses can be removed by rebooting the computer, entering Windows safe mode with networking, and then using system tools or Microsoft Safety Scanner.

Hardware implants can be of any type, so there can be no general way to detect them.

Website security scans

As

malware also harms the compromised websites (by breaking reputation,

blacklisting in search engines, etc.), some websites offer vulnerability

scanning.

Such scans check the website, detect malware, may note outdated software, and may report known security issues.

"Air gap" isolation or "parallel network"

As

a last resort, computers can be protected from malware, and infected

computers can be prevented from disseminating trusted information, by

imposing an "air gap"

(i.e. completely disconnecting them from all other networks). However,

malware can still cross the air gap in some situations. For example, removable media can carry malware across the gap. In December 2013 researchers in Germany showed one way that an apparent air gap can be defeated.

"AirHopper", "BitWhisper", "GSMem", and "Fansmitter" are four techniques introduced by researchers that can leak data from

air-gapped computers using electromagnetic, thermal and acoustic

emissions.

Grayware

Grayware is a term applied to unwanted applications or files that are

not classified as malware, but can worsen the performance of computers

and may cause security risks.

It describes applications that behave in an annoying or

undesirable manner, and yet are less serious or troublesome than

malware. Grayware encompasses spyware, adware, fraudulent dialers, joke programs, remote access tools

and other unwanted programs that may harm the performance of computers

or cause inconvenience. The term came into use around 2004.

Another term, potentially unwanted program (PUP) or potentially unwanted application (PUA),

refers to applications that would be considered unwanted despite often

having been downloaded by the user, possibly after failing to read a

download agreement. PUPs include spyware, adware, and fraudulent

dialers. Many security products classify unauthorised key generators as

grayware, although they frequently carry true malware in addition to

their ostensible purpose.

Software maker Malwarebytes lists several criteria for classifying a program as a PUP. Some types of adware (using stolen certificates) turn off anti-malware and virus protection; technical remedies are available.

History of viruses and worms

Before Internet access became widespread, viruses spread on personal computers by infecting the executable boot sectors of floppy disks. By inserting a copy of itself into the machine code instructions in these executables, a virus causes itself to be run whenever a program is run or the disk is booted. Early computer viruses were written for the Apple II and Macintosh, but they became more widespread with the dominance of the IBM PC and MS-DOS system. Executable-infecting

viruses are dependent on users exchanging software or boot-able

floppies and thumb drives so they spread rapidly in computer hobbyist

circles.

The first worms, network-borne infectious programs, originated not on personal computers, but on multitasking Unix systems. The first well-known worm was the Internet Worm of 1988, which infected SunOS and VAX BSD systems. Unlike a virus, this worm did not insert itself into other programs. Instead, it exploited security holes (vulnerabilities) in network server programs and started itself running as a separate process. This same behavior is used by today's worms as well.

With the rise of the Microsoft Windows platform in the 1990s, and the flexible macros of its applications, it became possible to write infectious code in the macro language of Microsoft Word and similar programs. These macro viruses infect documents and templates rather than applications (executables), but rely on the fact that macros in a Word document are a form of executable code.

Academic research

The notion of a self-reproducing computer program can be traced back

to initial theories about the operation of complex automata. John von Neumann showed that in theory a program could reproduce itself. This constituted a plausibility result in computability theory. Fred Cohen

experimented with computer viruses and confirmed Neumann's postulate

and investigated other properties of malware such as detectability and

self-obfuscation using rudimentary encryption. His doctoral dissertation

was on the subject of computer viruses.

The combination of cryptographic technology as part of the payload of

the virus, exploiting it for attack purposes was initialized and

investigated from the mid 1990s, and includes initial ransomware and

evasion ideas.