| |

| Other short titles | Endangered Species Act of 1973 |

|---|---|

| Long title | An Act to provide for the conservation of endangered and threatened species of fish, wildlife, and plants, and for other purposes. |

| Acronyms (colloquial) | ESA |

| Nicknames | Endangered Species Conservation Act |

| Enacted by | the 93rd United States Congress |

| Effective | December 27, 1973 |

| Citations | |

| Public law | 93–205 |

| Statutes at Large | 87 Stat. 884 |

| Codification | |

| Titles amended | 16 U.S.C.: Conservation |

| U.S.C. sections created | 16 U.S.C. ch. 35 § 1531 et seq. |

| Legislative history | |

| |

| Major amendments | |

| United States Supreme Court cases | |

| Lujan v. Defenders of Wildlife, 504 U.S. 555 (1992) Tennessee Valley Authority v. Hill, 437 U.S. 153 (1978) | |

The Endangered Species Act of 1973 serves as the enacting legislation to carry out the provisions outlined in The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES). Designed to protect critically imperiled species from extinction as a "consequence of economic growth and development untempered by adequate concern and conservation", the ESA was signed into law by President Richard Nixon on December 28, 1973. The law requires federal agencies to consult with the Fish and Wildlife Service &/or the NOAA Fisheries Service to ensure their actions are not likely to jeopardize the continued existence of any listed species or result in the destruction or adverse modification of designated critical habitat of such species. The U.S. Supreme Court found that "the plain intent of Congress in enacting" the ESA "was to halt and reverse the trend toward species extinction, whatever the cost." The Act is administered by two federal agencies, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS).

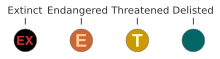

Listing status

U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA)

Listing status and its abbreviations used in Federal Register and by federal agencies like the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service:

- E = endangered (Sec.3.6, Sec.4.a) – any species which is in danger of extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range other than a species of the Class Insecta determined by the Secretary to constitute a pest.

- T = threatened (Sec.3.20, Sec.4.a) – any species which is likely to become an endangered species within the foreseeable future throughout all or a significant portion of its range

- Other categories:

- C = candidate (Sec.4.b.3) – a species under consideration for official listing

- E(S/A), T(S/A) = endangered or threatened due to similarity of appearance (Sec.4.e ) – a species not endangered or threatened, but so closely resembles in appearance a species which has been listed as endangered or threatened, that enforcement personnel would have substantial difficulty in attempting to differentiate between the listed and unlisted species.

- XE, XN = experimental essential or non-essential population (Sec.10.j ) – any population (including eggs, propagules, or individuals) of an endangered species or a threatened species released outside the current range under authorization of the Secretary. Experimental, nonessential populations of endangered species are treated as threatened species on public land, for consultation purposes, and as species proposed for listing on private land.

History

The near-extinction of the bison and the disappearance of the passenger pigeon helped drive the call for wildlife conservation starting in the 1900s. Ornithologist George Bird Grinnell wrote articles on the subject in the magazine Forest and Stream, while Joel Asaph Allen, founder of the American Ornithologists' Union, hammered away in the popular press. The public was introduced to a new concept: extinction.

Whooping crane

Market hunting for the millinery

trade and for the table was one aspect of the problem. The early

naturalists also killed birds and other wildlife for study, personal curio collections and museum pieces.

While habitat losses continued as communities and farmland grew, the

widespread use of pesticides and the introduction of non-native species

also affected wildlife.

One species in particular received widespread attention—the whooping crane. The species' historical range extended from central Canada south to Mexico, and from Utah to the Atlantic coast.

Unregulated hunting and habitat loss contributed to a steady decline in

the whooping crane population until, by 1890, it had disappeared from

its primary breeding range in the north central United States. It would

be another eight years before the first national law regulating

wildlife commerce was signed, and another two years before the first

version of the endangered species act was passed. The whooping crane

population by 1941 was estimated at about only 16 birds still in the

wild.

The Lacey Act of 1900

was the first federal law that regulated commercial animal markets. It

prohibited interstate commerce of animals killed in violation of state

game laws, and covered all fish and wildlife and their parts or

products, as well as plants. Other legislation followed, including the Migratory Bird Conservation Act of 1929, a 1937 treaty prohibiting the hunting of right and gray whales, and the Bald Eagle Protection Act of 1940. These later laws had a low cost to society–the species were relatively rare–and little opposition was raised.

Whereas the Lacey Act dealt with game animal management and

market commerce species, a major shift in focus occurred by 1963 to

habitat preservation instead of take regulations. A provision was added

by Congress in the Land and Water Conservation Fund Act of 1965 that

provided money for the "acquisition of land, waters...for the

preservation of species of fish and wildlife that are threatened with

extinction."

Act of 1966

The

predecessor of the ESA was the Endangered Species Preservation Act of

1966 (P.L. 89-669 ). Passed by Congress, this act permitted the listing

of native U.S. animal species as endangered and for limited protections upon those animals.

It authorized the Secretary of the Interior to list endangered

domestic fish and wildlife and allowed the United States Fish and

Wildlife Service to spend up to $15 million per year to buy habitats for

listed species. It also directed federal land agencies to preserve

habitat on their lands. The Act also consolidated and even expanded

authority for the Secretary of the Interior to manage and administer the

National Wildlife Refuge System. Other public agencies were encouraged, but not required, to protect species. The act did not address the commerce in endangered species and parts.

In March, 1967 the first list of endangered species was issued

under the act. It included 14 mammals, 36 birds, 6 reptiles and

amphibians and 22 fish.

This first list is referred to as the "Class of '67" in The Endangered Species Act at Thirty,

Volume 1, which concludes that habitat destruction, the biggest threat

to those 78 species, is still the same threat to the currently listed

species. It included only vertebrates because the Department of Interior's definition of "fish and wildlife" was limited to vertebrates.

However, with time, researchers noticed that the animals on the

endangered species list still were not getting enough protection, thus

further threatening their extinction. The endangered species program was

expanded by the Endangered Species Act of 1969.

Amendment of 1969

The Endangered Species Conservation Act

(P. L. 91–135), passed in December, 1969, amended the original law to

provide additional protection to species in danger of "worldwide

extinction" by prohibiting their importation and subsequent sale in the

United States. It expanded the Lacey Act's ban on interstate commerce

to include mammals, reptiles, amphibians, mollusks and crustaceans. Reptiles were added mainly to reduce the rampant poaching of alligators and crocodiles. This law was the first time that invertebrates were included for protection.

The amendment called for an international meeting to adopt a convention or treaty to conserve endangered species.

That meeting was held in Washington, D.C., in February, 1973 and produced the comprehensive multilateral treaty known as CITES or Convention on International Trade of Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora.

Endangered Species Act

President Richard Nixon declared current species conservation efforts to be inadequate and called on the 93rd United States Congress to pass comprehensive endangered species legislation.

Congress responded with a completely rewritten law, the Endangered

Species Act of 1973, which was signed by Nixon on December 28, 1973 (Pub.L. 93–205). It was written by a team of lawyers and scientists, including Dr. Russell E. Train, the first appointed head of the Council on Environmental Quality (CEQ), an outgrowth of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) of 1969.

Dr. Train was assisted by a core group of staffers, including Dr. Earl

Baysinger at EPA, Dick Gutting, and Dr. Gerard A. "Jerry" Bertrand, a

Ph.D marine biologist by training (Oregon State University), who had

transferred from his post as the scientific adviser to the U.S. Army

Corps of Engineers, office of the Commandant of the Corps, to join the

newly formed White House office.

The staff, under Dr. Train's leadership, incorporated dozens of new

principles and ideas into the landmark legislation, crafting a document

that completely changed the direction of environmental conservation in

the United States. Dr. Bertrand is credited with writing the most challenged section of the Act, the "takings" clause – Section 2.

The stated purpose of the Endangered Species Act is to protect

species and also "the ecosystems upon which they depend." California

historian Kevin Starr was more emphatic when he said: "The Endangered Species Act of 1982 is the Magna Carta of the environmental movement."

The ESA is administered by two federal agencies, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS). NMFS handles marine species, and the FWS has responsibility over freshwater fish and all other species. Species that occur in both habitats (e.g. sea turtles and Atlantic sturgeon) are jointly managed.

In March 2008, The Washington Post reported that documents showed that the Bush Administration, beginning in 2001, had erected "pervasive bureaucratic obstacles" that limited the number of species protected under the act:

- From 2000 to 2003, until a U.S. District Court overturned the decision, Fish and Wildlife Service officials said that if that agency identified a species as a candidate for the list, citizens could not file petitions for that species.

- Interior Department personnel were told they could use "info from files that refutes petitions but not anything that supports" petitions filed to protect species.

- Senior department officials revised a longstanding policy that rated the threat to various species based primarily on their populations within U.S. borders, giving more weight to populations in Canada and Mexico, countries with less extensive regulations than the U.S.

- Officials changed the way species were evaluated under the act by considering where the species currently lived, rather than where they used to exist.

- Senior officials repeatedly dismissed the views of scientific advisers who said that species should be protected.

In 2014, the House of Representatives passed the 21st Century

Endangered Species Transparency Act, which would require the government

to disclose the data it uses to determine species classification.

Preventing extinction

The

ESA's primary goal is to prevent the extinction of imperiled plant and

animal life, and secondly, to recover and maintain those populations by

removing or lessening threats to their survival.

Petition and listing

To be considered for listing, the species must meet one of five criteria (section 4(a)(1)):

2. An over utilization for commercial, recreational, scientific, or educational purposes.

3. The species is declining due to disease or predation.

4. There is an inadequacy of existing regulatory mechanisms.

5. There are other natural or manmade factors affecting its continued existence.

Potential candidate species are then prioritized, with "emergency

listing" given the highest priority. Species that face a "significant

risk to their well being" are in this category.

A species can be listed in two ways. The United States Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) or NOAA Fisheries (also called the National Marine Fisheries Service)

can directly list a species through its candidate assessment program,

or an individual or organizational petition may request that the FWS or

NMFS list a species. A "species" under the act can be a true taxonomic species, a subspecies, or in the case of vertebrates, a "distinct population segment." The procedures are the same for both types except with the person/organization petition, there is a 90-day screening period.

During the listing process, economic factors cannot be

considered, but must be " based solely on the best scientific and

commercial data available."

The 1982 amendment to the ESA added the word "solely" to prevent any

consideration other than the biological status of the species. Congress

rejected President Ronald Reagan's Executive Order 12291

which required economic analysis of all government agency actions. The

House committee's statement was "that economic considerations have no

relevance to determinations regarding the status of species."

The very opposite result happened with the 1978 amendment where

Congress added the words "...taking into consideration the economic

impact..." in the provision on critical habitat designation.

The 1978 amendment linked the listing procedure with critical habitat

designation and economic considerations, which almost completely halted

new listings, with almost 2,000 species being withdrawn from

consideration.

Listing process

After

receiving a petition to list a species, the two federal agencies take

the following steps, or rulemaking procedures, with each step being

published in the Federal Register, the US government's official journal of proposed or adopted rules and regulations:

1. If a petition presents information that the species may be

imperiled, a screening period of 90 days begins (interested persons

and/or organization petitions only). If the petition does not present

substantial information to support listing, it is denied.

2. If the information is substantial, a status review is

started, which is a comprehensive assessment of a species' biological

status and threats, with a result of : "warranted", "not warranted," or

"warranted but precluded."

- A finding of not warranted, the listing process ends.

- Warranted finding means the agencies publish a 12-month finding (a proposed rule) within one year of the date of the petition, proposing to list the species as threatened or endangered. Comments are solicited from the public, and one or more public hearings may be held. Three expert opinions from appropriate and independent specialists may be included, but this is voluntary.

- A "warranted but precluded" finding is automatically recycled back through the 12-month process indefinitely until a result of either "not warranted" or "warranted" is determined. The agencies monitor the status of any "warranted but precluded" species.

Essentially the "warranted but precluded" finding is a deferral added

by the 1982 amendment to the ESA. It means other, higher-priority

actions will take precedence.

For example, an emergency listing of a rare plant growing in a wetland

that is scheduled to be filled in for housing construction would be a

"higher-priority".

3. Within another year, a final determination (a final rule) must

be made on whether to list the species. The final rule time limit may

be extended for 6 months and listings may be grouped together according

to similar geography, threats, habitat or taxonomy.

The annual rate of listing (i.e., classifying species as "threatened" or "endangered") increased steadily from the Ford administration (47 listings, 15 per year) through Carter (126 listings, 32 per year), Reagan (255 listings, 32 per year), George H. W. Bush (231 listings, 58 per year), and Clinton (521 listings, 65 per year) before decline to its lowest rate under George W. Bush (60 listings, 8 per year as of 5/24/08).

The rate of listing is strongly correlated with citizen

involvement and mandatory timelines: as agency discretion decreases and

citizen involvement increases (i.e. filing of petitions and lawsuits)

the rate of listing increases. Citizen involvement has been shown to identify species not moving through the process efficiently, and identify more imperiled species. The longer species are listed, the more likely they are to be classified as recovering by the FWS.

Public notice, comments and judicial review

Public notice

is given through legal notices in newspapers, and communicated to state

and county agencies within the species' area. Foreign nations may also

receive notice of a listing.

A public hearing is mandatory if any person has requested one within 45 days of the published notice.

"The purpose of the notice and comment requirement is to provide for

meaningful public participation in the rulemaking process." summarized

the Ninth Circuit court in the case of Idaho Farm Bureau Federation v. Babbitt.

Species survival and recovery

Critical habitat

The provision of the law in Section 4 that establishes critical habitat

is a regulatory link between habitat protection and recovery goals,

requiring the identification and protection of all lands, water and air

necessary to recover endangered species.

To determine what exactly is critical habitat, the needs of open space

for individual and population growth, food, water, light or other

nutritional requirements, breeding sites, seed germination and dispersal

needs, and lack of disturbances are considered.

As habitat loss is the primary threat to most imperiled species,

the Endangered Species Act of 1973 allowed the Fish and Wildlife Service

(FWS) and National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) to designate

specific areas as protected "critical habitat" zones. In 1978, Congress

amended the law to make critical habitat designation a mandatory

requirement for all threatened and endangered species.

The amendment also added economics

into the process of determining habitat: "...shall designate critical

habitat... on the basis of the best scientific data available and after

taking into consideration the economic impact, and any other impact, of

specifying... area as critical habitat."

The congressional report on the 1978 amendment described the conflict

between the new Section 4 additions and the rest of the law:

"... the critical habitat provision is a startling section which is wholly inconsistent with the rest of the legislation. It constitutes a loophole which could readily be abused by any Secretary ... who is vulnerable to political pressure or who is not sympathetic to the basic purposes of the Endangered Species Act."-- House of Representatives Report 95-1625, at 69 (1978)

The amendment of 1978 added economic considerations and the 1982 amendment prevented economic considerations.

Several studies on the effect of critical habitat designation on

species' recovery rates have been done between 1997 and 2003. Although

it has been criticized, the Taylor study in 2003 found that, "species with critical habitat were... twice as likely to be improving...."

Critical habitats are required to contain "all areas essential to

the conservation" of the imperiled species, and may be on private or

public lands. The Fish and Wildlife Service has a policy limiting

designation to lands and waters within the U.S. and both federal

agencies may exclude essential areas if they determine that economic or

other costs exceed the benefit. The ESA is mute about how such costs and

benefits are to be determined.

All federal agencies are prohibited from authorizing, funding or

carrying out actions that "destroy or adversely modify" critical

habitats (Section 7(a) (2)). While the regulatory aspect of critical

habitat does not apply directly to private and other non-federal

landowners, large-scale development, logging and mining

projects on private and state land typically require a federal permit

and thus become subject to critical habitat regulations. Outside or in

parallel with regulatory processes, critical habitats also focus and

encourage voluntary actions such as land purchases, grant making,

restoration, and establishment of reserves.

The ESA requires that critical habitat be designated at the time

of or within one year of a species being placed on the endangered list.

In practice, most designations occur several years after listing. Between 1978 and 1986 the FWS regularly designated critical habitat. In 1986 the Reagan Administration issued a regulation

limiting the protective status of critical habitat. As a result, few

critical habitats were designated between 1986 and the late 1990s. In

the late 1990s and early 2000s, a series of court orders

invalidated the Reagan regulations and forced the FWS and NMFS to

designate several hundred critical habitats, especially in Hawaii,

California and other western states. Midwest and Eastern states received

less critical habitat, primarily on rivers and coastlines. As of

December, 2006, the Reagan regulation has not yet been replaced though

its use has been suspended. Nonetheless, the agencies have generally

changed course and since about 2005 have tried to designate critical

habitat at or near the time of listing.

Most provisions of the ESA revolve around preventing extinction.

Critical habitat is one of the few that focus on recovery. Species with

critical habitat are twice as likely to be recovering as species without

critical habitat.

Plans, permits, and agreements

The

combined result of the amendments to the Endangered Species Act have

created a law vastly different from the ESA of 1973. It is now a

flexible, permitting statute. For example, the law now permits

"incidental takes" (accidental killing or harming a listed species).

Congress added the requirements for "incidental take statement", and

authorized a "incidental take permit" in conjunction with "habitat

conservation plans".

More changes were made in the 1990s in an attempt by Secretary of the Interior Bruce Babbitt

to shield the ESA from a Congress hostile to the law. He instituted

incentive-based strategies such as candidate conservation agreements and

"safe harbor" agreements that would balance the goals of economic development and conservation.

Recovery plan

Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) and National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) are required to create an Endangered Species Recovery Plan

outlining the goals, tasks required, likely costs, and estimated

timeline to recover endangered species (i.e., increase their numbers and

improve their management to the point where they can be removed from

the endangered list).

The ESA does not specify when a recovery plan must be completed. The

FWS has a policy specifying completion within three years of the species

being listed, but the average time to completion is approximately six

years.

The annual rate of recovery plan completion increased steadily from the

Ford administration (4) through Carter (9), Reagan (30), Bush I (44),

and Clinton (72), but declined under Bush II (16 per year as of 9/1/06).

The goal of the law is to make itself unnecessary, and recovery plans are a means toward that goal.

Recovery plans became more specific after 1988 when Congress added

provisions to Section 4(f) of the law that spelled out the minimum

contents of a recovery plan. Three types of information must be

included:

- A description of "site-specific" management actions to make the plan as explicit as possible.

- The "objective, measurable criteria" to serve as a baseline for judging when and how well a species is recovering.

- An estimate of money and resources needed to achieve the goal of recovery and delisting.

The amendment also added public

participation to the process. There is a ranking order, similar to the

listing procedures, for recovery plans, with the highest priority being

for species most likely to benefit from recovery plans, especially when

the threat is from construction, or other developmental or economic

activity. Recovery plans cover domestic and migratory species.

Exemptions

Exemptions can and do occur. The ESA requires federal agencies to consult with the US Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) or the National Marine Fisheries Service (NMFS) if any project occurs in the habitat of a listed species. An example of such a project might be a timber harvest proposed by the US Forest Service.

If the timber harvest could impact a listed species, a biological

assessment is prepared by the Forest Service and reviewed by the FWS or

NMFS or both.

The question to be answered is whether a listed species will be

harmed by the action and, if so, how the harm can be minimized. If harm

cannot be avoided, the project agency can seek an exemption from the

Endangered Species Committee, an ad hoc panel composed of members from

the executive branch and at least one appointee from the state where the

project is to occur. Five of the seven committee members must vote for

the exemption to allow taking (to harass, harm, pursue, hunt, shoot,

wound, kill, trap, capture, or collect, or significant habitat

modification, or to attempt to engage in any such conduct) of listed species.

Long before the exemption is considered by the Endangered Species

Committee, the Forest Service, and either the FWS or the NMFS will have

consulted on the biological implications of the timber harvest. The

consultation can be informal, to determine if harm may occur; and then

formal if the harm is believed to be likely. The questions to be

answered in these consultations are whether the species will be harmed,

whether the habitat will be harmed and if the action will aid or hinder

the recovery of the listed species.

If harm is likely to occur, the consultation evaluates whether

"reasonable and prudent alternatives" exist to minimize harm. If an

alternative does not exist, the FWS or NMFS will issue an opinion that

the action constitutes "jeopardy" to the listed species either directly

or indirectly. The project cannot then occur unless exempted by the

Endangered Species Committee.

The Committee must make a decision on the exemption within 30 days, when its findings are published in the Federal Register. The findings can be challenged in federal court. In 1992, one such challenge was the case of Portland Audubon Society v. Endangered Species Committee heard in the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals.

The court found that three members had been in illegal ex parte contact with the then-President George H.W. Bush, a violation of the Administrative Procedures Act. The committee's exemption was for the Bureau of Land Management's timber sale and "incidental takes" of the endangered northern spotted owl in Oregon.

There have been six instances as of 2009 in which the exemption

process was initiated. Of these six, one was granted, one was partially

granted, one was denied and three were withdrawn.

Donald Baur, in The Endangered Species Act: law, policy, and perspectives,

concluded," ... the exemption provision is basically a nonfactor in the

administration of the ESA. A major reason, of course, is that so few

consultations result in jeopardy opinions, and those that do almost

always result in the identification of reasonable and prudent

alternatives to avoid jeopardy."

Habitat Conservation Plans

More

than half of habitat for listed species is on non-federal property,

owned by citizens, states, local governments, tribal governments and

private organizations. Before the law was amended in 1982, a listed species could be taken only for scientific or research purposes. The amendment created a permit process to circumvent the take prohibition called a Habitat Conservation Plan

or HCP to give incentives to non-federal land managers and private

landowners to help protect listed and unlisted species, while allowing

economic development that may harm ("take") the species.

The US Fish and Wildlife Service

defines the process as: "The purpose of the habitat conservation

planning process associated with the permit is to ensure there is

adequate minimizing and mitigating of the effects of the authorized

incidental take. The purpose of the incidental take permit is to

authorize the incidental take of a listed species, not to authorize the

activities that result in take."

The person or organization submits a HCP and if approved by the agency (FWS or NMFS), will be issued an Incidental Take Permit

(ITP) which allows a certain number of "takes" of the listed species.

The permit may be revoked at any time and can allow incidental takes for

varying amounts of time. For instance, the San Bruno Habitat

Conservation Plan/ Incidental Take Permit is good for 30 years and the

Wal-Mart store (in Florida) permit expires after one year. Because the

permit is issued by a federal agency to a private party, it is a federal

action-which means other federal laws can apply, such as the National Environmental Policy Act or NEPA. A notice of the permit application action is published in the Federal Register and a public comment period of 30 to 90 days begins.

The US Congress was urged to create the exemption by proponents of a conservation plan on San Bruno Mountain,

California that was drafted in the early 1980s and is the first HCP in

the nation. In the conference report on the 1982 amendments, Congress

specified that it intended the San Bruno plan to act "as a model" for

future conservation plans developed under the incidental take exemption

provision and that "the adequacy of similar conservation plans should be

measured against the San Bruno plan". Congress further noted that the

San Bruno plan was based on "an independent exhaustive biological study"

and protected at least 87% of the habitat of the listed butterflies

that led to the development of the HCP.

Growing scientific recognition of the role of private lands for

endangered species recovery and the landmark 1981 court decision in Palila v. Hawaii Department of Land and Natural Resources

both contributed to making Habitat Conservation Plans/ Incidental Take

Permits "a major force for wildlife conservation and a major headache

to the development community", wrote Robert D. Thornton in the 1991 Environmental Law article, Searching for Consensus and Predictability: Habitat Conservation Planning under the Endangered Species Act of 1973.

"No Surprises" rule

The

"No Surprises" rule is meant to protect the landowner if "unforeseen

circumstances" occur which make the landowner's efforts to prevent or

mitigate harm to the species fall short. The "No Surprises" policy may

be the most controversial of the recent reforms of the law, because once

an Incidental Take Permit is granted, the Fish and Wildlife Service

(FWS) loses much ability to further protect a species if the mitigation

measures by the landowner prove insufficient. The landowner or permittee

would not be required to set aside additional land or pay more in

conservation money. The federal government would have to pay for

additional protection measures.

"Safe Harbor" agreements

The

"Safe Harbor" agreement is a voluntary agreement between the private

landowner and FWS. The landowner agrees to alter the property to benefit

or even attract a listed or proposed species in exchange for assurances

that the FWS will permit future "takes" above a pre-determined level.

The policy relies on the "enhancement of survival" provision of Section

§1539(a)(1)(A). A landowner can have either a "Safe Harbor" agreement

or an Incidental Take Permit, or both. The policy was developed by the

Clinton Administration in 1999.

Candidate Conservation Agreements

The

Candidate Conservation Agreement is closely related to the "Safe

Harbor" agreement, the main difference is that the Candidate

Conservation Agreements With Assurances(CCA) are meant to protect unlisted

species by providing incentives to private landowners and land managing

agencies to restore, enhance or maintain habitat of unlisted species

which are declining and have the potential to become threatened or

endangered if critical habitat is not protected. The FWS will then

assure that if, in the future the unlisted species becomes listed, the

landowner will not be required to do more than already agreed upon in

the CCA.

Experimental Populations

The

Experimental Population Provision encourages introductions of species

into formerly occupied or new habitat without the full range of legal

restrictions for endangered species. The provision was added to the act

in 1982 to encourage landowner support for species survival and

recovery. Experimental populations could be used for the assisted migration of endangered species.

Delisting

To delist species, several factors are considered: the threats are

eliminated or controlled, population size and growth, and the stability

of habitat quality and quantity. Also, over a dozen species have been

delisted due to inaccurate data putting them on the list in the first

place.

There is also "downlisting" of a species where some of the

threats have been controlled and the population has met recovery

objectives, then the species can be reclassified to "threatened" from

"endangered."

Two examples of animal species recently delisted are: the Virginia northern flying squirrel (subspecies) on August, 2008, which had been listed since 1985, and the gray wolf

(Northern Rocky Mountain DPS). On April 15, 2011, President Obama

signed the Department of Defense and Full-Year Appropriations Act of

2011.

A section of that Appropriations Act directed the Secretary of the

Interior to reissue within 60 days of enactment the final rule published

on April 2, 2009, that identified the Northern Rocky Mountain

population of gray wolf (Canis lupus) as a distinct population

segment (DPS) and to revise the List of Endangered and Threatened

Wildlife by removing most of the gray wolves in the DPS.

The US Fish and Wildlife Service's delisting report lists four plants that have recovered:

- Eggert's sunflower (Helianthus eggertii)

- Robbins' cinquefoil (Potentilla robbinsiana), an alpine wildflower found in the White Mountains of New Hampshire

- Maguire daisy (Erigeron maguirei)

- Tennessee purple coneflower (Echinacea tennesseensis)

Effectiveness

Positive effects

As

of January 2019, eighty-five species have been delisted; fifty-four due

to recovery, eleven due to extinction, seven due to changes in

taxonomic classification practices, six due to discovery of new

populations, five due to an error in the listing rule, one due to

erroneous data and one due to an amendment to the Endangered Species Act

specifically requiring the species delisting. Twenty-five others have been down listed from "endangered" to "threatened" status.

Some have argued that the recovery of DDT-threatened species such as the bald eagle, brown pelican and peregrine falcon should be attributed to the 1972 ban on DDT by the EPA.

rather than the Endangered Species Act, however, the listing of these

species as endangered was a substantial cause of Congress instituting

the ban and many non-DDT oriented actions were taken on their behalf

under the Endangered Species Act (i.e. captive breeding, habitat

protection, and protection from disturbance).

As of January 2019, there are 1,467 total (foreign and domestic)

species on the threatened and endangered lists. However, many species

have become extinct while on the candidate list or otherwise under

consideration for listing.

Species which increased in population size since being placed on the endangered list include:

- Bald eagle (increased from 417 to 11,040 pairs between 1963 and 2007); removed from list 2007

- Whooping crane (increased from 54 to 436 birds between 1967 and 2003)

- Kirtland's warbler (increased from 210 to 1,415 pairs between 1971 and 2005)

- Peregrine falcon (increased from 324 to 1,700 pairs between 1975 and 2000); removed from list 1999

- Gray wolf (populations increased dramatically in the Northern Rockies and Western Great Lakes States)

- Mexican wolf (increased to minimum population of 109 wolves in 2014 in southwest New Mexico and southeast Arizona)

- Red wolf (increased from 17 in 1980 to 257 in 2003)

- Gray whale (increased from 13,095 to 26,635 whales between 1968 and 1998); removed from list (Debated because whaling was banned before the ESA was set in place and that the ESA had nothing to do with the natural population increase since the cease of massive whaling [excluding Native American tribal whaling])

- Grizzly bear (increased from about 271 to over 580 bears in the Yellowstone area between 1975 and 2005); removed from list March 22, 2007

- California’s southern sea otter (increased from 1,789 in 1976 to 2,735 in 2005)

- San Clemente Indian paintbrush (increased from 500 plants in 1979 to more than 3,500 in 1997)

- Florida's Key deer (increased from 200 in 1971 to 750 in 2001)

- Big Bend gambusia (increased from a couple dozen to a population of over 50,000)

- Hawaiian goose (increased from 400 birds in 1980 to 1,275 in 2003)

- Virginia big-eared bat (increased from 3,500 in 1979 to 18,442 in 2004)

- Black-footed ferret (increased from 18 in 1986 to 600 in 2006)

Criticism

Opponents of the Endangered Species Act argue that with over 2,000 endangered species listed,

and only 28 delisted due to recovery, the success rate of 1% over

nearly three decades proves that there needs to be serious reform in

their methods to actually help the endangered animals and plants.

Others argue that the ESA may encourage preemptive habitat destruction

by landowners who fear losing the use of their land because of the

presence of an endangered species; known colloquially as "Shoot, Shovel and Shut-Up." One example of such perverse incentives is the case of a forest owner who, in response to ESA listing of the red-cockaded woodpecker,

increased harvesting and shortened the age at which he harvests his

trees to ensure that they do not become old enough to become suitable

habitat.

While no studies have shown that the Act's negative effects, in total,

exceed the positive effects, many economists believe that finding a way

to reduce such perverse incentives would lead to more effective

protection of endangered species.

According to research published in 1999 by Alan Green and the Center for Public Integrity (CPI), loopholes in the ESA are commonly exploited in the exotic pet trade.

Although the legislation prohibits interstate and foreign transactions

for list species, no provisions are made for in-state commerce, allowing

these animals to be sold to roadside zoos

and private collectors. Additionally, the ESA allows listed species to

be shipped across state lines as long as they are not sold. According to

Green and the CPI, this allows dealers to "donate" listed species

through supposed "breeding loans" to anyone, and in return they can

legally receive a reciprocal monetary "donation" from the receiving

party. Furthermore, an interview with an endangered species specialist at the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service

revealed that the agency does not have sufficient staff to perform

undercover investigations, which would catch these false "donations" and

other mislabeled transactions.

Green and the CPI further noted another exploit of the ESA in their discussion of the critically endangered cotton-top tamarin (Saguinus oedipus). Not only had they found documentation that 151 of these primates had inadvertently made their way from the Harvard-affiliated New England Regional Primate Research Center into the exotic pet trade through the aforementioned loophole,

but in October 1976, over 800 cotton-top tamarins were imported into

the United States in order to beat the official listing of the species

under the ESA.

State endangered species lists

Section 6 of the Endangered Species Act provided funding for development of programs for management of threatened and endangered species by state wildlife agencies.

Subsequently, lists of endangered and threatened species within their

boundaries have been prepared by each state. These state lists often

include species which are considered endangered or threatened within a

specific state but not within all states, and which therefore are not

included on the national list of endangered and threatened species.

Examples include Florida, Minnesota, Maine,

Penalties

There

are different degrees of violation with the law. The most punishable

offenses are trafficking, and any act of knowingly "taking" (which

includes harming, wounding, or killing) an endangered species.

The penalties for these violations can be a maximum fine of up to $50,000 or imprisonment for one year, or both, and civil penalties of up to $25,000 per violation may be assessed. Lists of violations and exact fines are available through the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration web-site.

One provision of this law is that no penalty may be imposed if, by a preponderance of the evidence

that the act was in self-defense. The law also eliminates criminal

penalties for accidentally killing listed species during farming and

ranching activities.

In addition to fines or imprisonment, a license, permit, or other

agreement issued by a federal agency that authorized an individual to

import or export fish, wildlife, or plants may be revoked, suspended or

modified. Any federal hunting or fishing permits that were issued to a

person who violates the ESA can be canceled or suspended for up to a

year.

Use of money received through violations of the ESA

A

reward will be paid to any person who furnishes information which leads

to an arrest, conviction, or revocation of a license, so long as they

are not a local, state, or federal employee in the performance of

official duties. The Secretary may also provide reasonable and

necessary costs incurred for the care of fish, wildlife, and forest

service or plant pending the violation caused by the criminal. If the

balance ever exceeds $500,000 the Secretary of the Treasury is required

to deposit an amount equal to the excess into the cooperative endangered

species conservation fund.