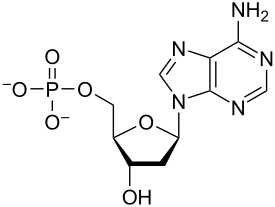

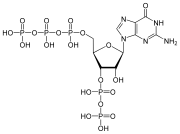

This nucleotide contains the five-carbon sugar deoxyribose (at center), a nitrogenous base called adenine (upper right), and one phosphate group (left). The deoxyribose sugar joined only to the nitrogenous base forms a Deoxyribonucleoside called deoxyadenosine, whereas the whole structure along with the phosphate group is a nucleotide, a constituent of DNA with the name deoxyadenosine monophosphate.

Nucleotides are organic molecules consisting of a nucleoside and a phosphate. They serve as monomeric units of the nucleic acid polymers deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA), both of which are essential biomolecules within all life-forms on Earth.

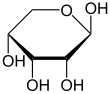

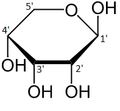

Nucleotides are composed of three subunit molecules: a nitrogenous base (also known as nucleobase), a five-carbon sugar (ribose or deoxyribose), and a phosphate group consisting of one to three phosphates. The four nitrogenous bases in DNA are guanine, adenine, cytosine and thymine; in RNA, uracil is used in place of thymine.

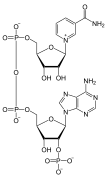

Nucleotides also play a central role in metabolism at a fundamental, cellular level. They provide chemical energy—in the form of the nucleoside triphosphates, adenosine triphosphate (ATP), guanosine triphosphate (GTP), cytidine triphosphate (CTP) and uridine triphosphate (UTP)—throughout the cell for the many cellular functions that demand energy, including: amino acid, protein and cell membrane synthesis, moving the cell and cell parts (both internally and intercellularly), cell division, etc. In addition, nucleotides participate in cell signaling (cyclic guanosine monophosphate or cGMP and cyclic adenosine monophosphate or cAMP), and are incorporated into important cofactors of enzymatic reactions (e.g. coenzyme A, FAD, FMN, NAD, and NADP+).

In experimental biochemistry, nucleotides can be radiolabeled using radionuclides to yield radionucleotides.

Structure

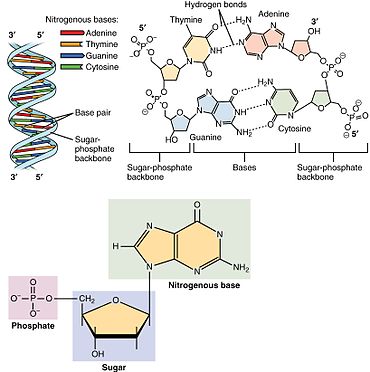

Showing

the arrangement of nucleotides within the structure of nucleic acids:

At lower left, a monophosphate nucleotide; its nitrogenous base

represents one side of a base-pair. At upper right, four nucleotides

form two base-pairs: thymine and adenine (connected by double hydrogen bonds) and guanine and cytosine (connected by triple

hydrogen bonds). The individual nucleotide monomers are chain-joined at

their sugar and phosphate molecules, forming two 'backbones' (a double helix) of a nucleic acid, shown at upper left.

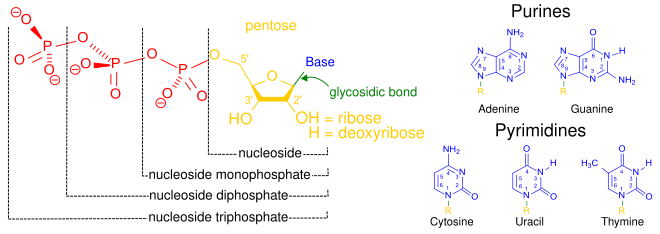

A nucleotide is composed of three distinctive chemical sub-units: a five-carbon sugar molecule, a nitrogenous base—which two together are called a nucleoside—and one phosphate group. With all three joined, a nucleotide is also termed a "nucleoside monophosphate", "nucleoside diphosphate" or "nucleoside triphosphate", depending on how many phosphates make up the phosphate group.

In nucleic acids, nucleotides contain either a purine or a pyrimidine base—i.e., the nitrogenous base molecule, also known as a nucleobase—and are termed ribonucleotides if the sugar is ribose, or deoxyribonucleotides if the sugar is deoxyribose. Individual phosphate molecules repetitively connect the sugar-ring

molecules in two adjacent nucleotide monomers, thereby connecting the

nucleotide monomers of a nucleic acid end-to-end into a long chain.

These chain-joins of sugar and phosphate molecules create a 'backbone'

strand for a single- or double helix. In any one strand, the chemical orientation (directionality) of the chain-joins runs from the 5'-end to the 3'-end (read:

5 prime-end to 3 prime-end)—referring to the five carbon sites on sugar

molecules in adjacent nucleotides. In a double helix, the two strands

are oriented in opposite directions, which permits base pairing and complementarity between the base-pairs, all which is essential for replicating or transcribing the encoded information found in DNA.

Nucleic acids then are polymeric macromolecules assembled from nucleotides, the monomer-units of nucleic acids. The purine bases adenine and guanine and pyrimidine base cytosine occur in both DNA and RNA, while the pyrimidine bases thymine (in DNA) and uracil (in RNA) occur in just one. Adenine forms a base pair with thymine with two hydrogen bonds, while guanine pairs with cytosine with three hydrogen bonds.

In addition to being building blocks for construction of nucleic

acid polymers, singular nucleotides play roles in cellular energy

storage and provision, cellular signaling, as a source of phosphate

groups used to modulate the activity of proteins and other signaling

molecules, and as enzymatic cofactors, often carrying out redox reactions. Signaling cyclic nucleotides are formed by binding the phosphate group twice to the same sugar molecule, bridging the 5'- and 3'- hydroxyl groups of the sugar.

Some signaling nucleotides differ from the standard single-phosphate

group configuration, in having multiple phosphate groups attached to

different positions on the sugar. Nucleotide cofactors include a wider range of chemical groups attached to the sugar via the glycosidic bond, including nicotinamide and flavin, and in the latter case, the ribose sugar is linear rather than forming the ring seen in other nucleotides.

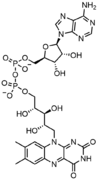

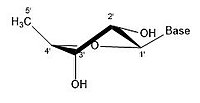

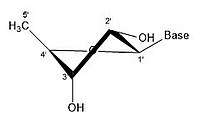

Structural elements of three nucleotides—where one-, two- or three-phosphates are attached to the nucleoside (in yellow, blue, green) at center: 1st, the nucleotide termed as a nucleoside monophosphate is formed by adding a phosphate (in red); 2nd, adding a second phosphate forms a nucleoside diphosphate; 3rd, adding a third phosphate results in a nucleoside triphosphate. + The nitrogenous base (nucleobase) is indicated by "Base" and "glycosidic bond" (sugar bond). All five primary, or canonical, bases—the purines and pyrimidines—are sketched at right (in blue).

Examples of non-nucleic acid nucleotides

Synthesis

In vitro, protecting groups may be used during laboratory production of nucleotides. A purified nucleoside is protected to create a phosphoramidite, which can then be used to obtain analogues not found in nature and/or to synthesize an oligonucleotide.

In vivo, nucleotides can be synthesized de novo or recycled through salvage pathways. The components used in de novo nucleotide synthesis are derived from biosynthetic precursors of carbohydrate and amino acid

metabolism, and from ammonia and carbon dioxide. The liver is the major

organ of de novo synthesis of all four nucleotides. De novo synthesis

of pyrimidines and purines follows two different pathways. Pyrimidines

are synthesized first from aspartate and carbamoyl-phosphate in the

cytoplasm to the common precursor ring structure orotic acid, onto which

a phosphorylated ribosyl unit is covalently linked. Purines, however,

are first synthesized from the sugar template onto which the ring

synthesis occurs. For reference, the syntheses of the purine and pyrimidine nucleotides are carried out by several enzymes in the cytoplasm of the cell, not within a specific organelle. Nucleotides undergo breakdown such that useful parts can be reused in synthesis reactions to create new nucleotides.

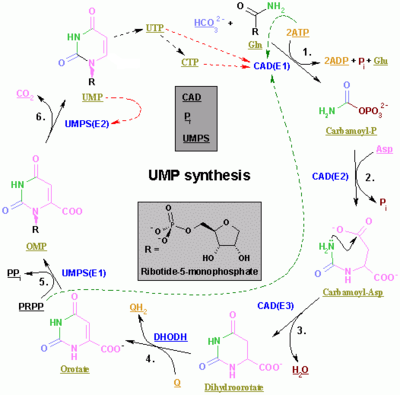

Pyrimidine ribonucleotide synthesis

The synthesis of UMP.

The color scheme is as follows: enzymes, coenzymes, substrate names, inorganic molecules

The synthesis of the pyrimidines CTP and UTP occurs in the cytoplasm and starts with the formation of carbamoyl phosphate from glutamine and CO2. Next, aspartate carbamoyltransferase catalyzes a condensation reaction between aspartate and carbamoyl phosphate to form carbamoyl aspartic acid, which is cyclized into 4,5-dihydroorotic acid by dihydroorotase. The latter is converted to orotate by dihydroorotate oxidase. The net reaction is:

- (S)-Dihydroorotate + O2 → Orotate + H2O2

Orotate is covalently linked with a phosphorylated ribosyl unit. The

covalent linkage between the ribose and pyrimidine occurs at position C1 of the ribose unit, which contains a pyrophosphate, and N1 of the pyrimidine ring. Orotate phosphoribosyltransferase (PRPP transferase) catalyzes the net reaction yielding orotidine monophosphate (OMP):

- Orotate + 5-Phospho-α-D-ribose 1-diphosphate (PRPP) → Orotidine 5'-phosphate + Pyrophosphate

Orotidine 5'-monophosphate

is decarboxylated by orotidine-5'-phosphate decarboxylase to form

uridine monophosphate (UMP). PRPP transferase catalyzes both the

ribosylation and decarboxylation reactions, forming UMP from orotic acid

in the presence of PRPP. It is from UMP that other pyrimidine

nucleotides are derived. UMP is phosphorylated by two kinases to

uridine triphosphate (UTP) via two sequential reactions with ATP. First

the diphosphate form UDP is produced, which in turn is phosphorylated

to UTP. Both steps are fueled by ATP hydrolysis:

- ATP + UMP → ADP + UDP

- UDP + ATP → UTP + ADP

CTP is subsequently formed by amination of UTP by the catalytic activity of CTP synthetase. Glutamine is the NH3 donor and the reaction is fueled by ATP hydrolysis, too:

- UTP + Glutamine + ATP + H2O → CTP + ADP + Pi

Cytidine monophosphate (CMP) is derived from cytidine triphosphate (CTP) with subsequent loss of two phosphates.

Purine ribonucleotide synthesis

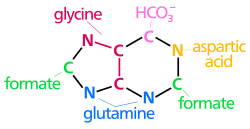

The atoms that are used to build the purine nucleotides come from a variety of sources:

The synthesis of IMP. The color scheme is as follows: enzymes, coenzymes, substrate names, metal ions, inorganic molecules

|

The biosynthetic origins of purine ring atoms N1 arises from the amine group of Asp C2 and C8 originate from formate N3 and N9 are contributed by the amide group of Gln C4, C5 and N7 are derived from Gly C6 comes from HCO3− (CO2) |

The de novo synthesis of purine nucleotides by which these precursors are incorporated into the purine ring proceeds by a 10-step pathway to the branch-point intermediate IMP, the nucleotide of the base hypoxanthine. AMP and GMP are subsequently synthesized from this intermediate via separate, two-step pathways. Thus, purine moieties are initially formed as part of the ribonucleotides rather than as free bases.

Six enzymes take part in IMP synthesis. Three of them are multifunctional:

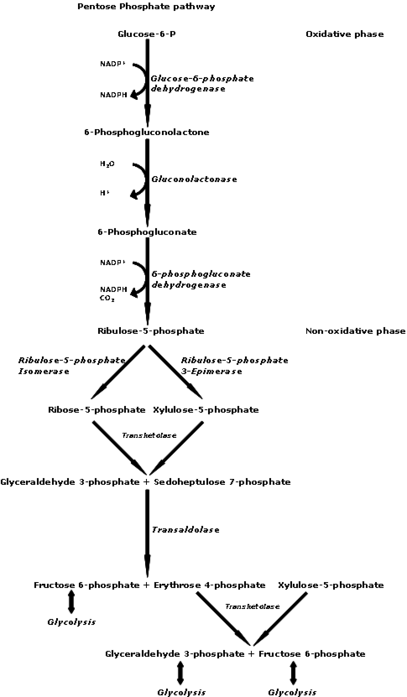

The pathway starts with the formation of PRPP. PRPS1 is the enzyme that activates R5P, which is formed primarily by the pentose phosphate pathway, to PRPP by reacting it with ATP. The reaction is unusual in that a pyrophosphoryl group is directly transferred from ATP to C1 of R5P and that the product has the α configuration about C1. This reaction is also shared with the pathways for the synthesis of Trp, His, and the pyrimidine nucleotides. Being on a major metabolic crossroad and requiring much energy, this reaction is highly regulated.

In the first reaction unique to purine nucleotide biosynthesis, PPAT catalyzes the displacement of PRPP's pyrophosphate group (PPi) by an amide nitrogen donated from either glutamine (N), glycine (N&C), aspartate (N), folic acid (C1), or CO2. This is the committed step in purine synthesis. The reaction occurs with the inversion of configuration about ribose C1, thereby forming β-5-phosphorybosylamine (5-PRA) and establishing the anomeric form of the future nucleotide.

Next, a glycine is incorporated fueled by ATP hydrolysis and the carboxyl group forms an amine bond to the NH2 previously introduced. A one-carbon unit from folic acid coenzyme N10-formyl-THF

is then added to the amino group of the substituted glycine followed by

the closure of the imidazole ring. Next, a second NH2 group

is transferred from a glutamine to the first carbon of the glycine unit.

A carboxylation of the second carbon of the glycin unit is

concomitantly added. This new carbon is modified by the additional of a

third NH2 unit, this time transferred from an aspartate

residue. Finally, a second one-carbon unit from formyl-THF is added to

the nitrogen group and the ring covalently closed to form the common

purine precursor inosine monophosphate (IMP).

Inosine monophosphate is converted to adenosine monophosphate in

two steps. First, GTP hydrolysis fuels the addition of aspartate to IMP

by adenylosuccinate synthase, substituting the carbonyl oxygen for a

nitrogen and forming the intermediate adenylosuccinate. Fumarate is then

cleaved off forming adenosine monophosphate. This step is catalyzed by

adenylosuccinate lyase.

Inosine monophosphate is converted to guanosine monophosphate by

the oxidation of IMP forming xanthylate, followed by the insertion of an

amino group at C2. NAD+ is the electron acceptor in the oxidation reaction. The amide group transfer from glutamine is fueled by ATP hydrolysis.

Pyrimidine and purine degradation

In humans, pyrimidine rings (C, T, U) can be degraded completely to CO2 and NH3 (urea excretion). That having been said, purine rings (G, A) cannot. Instead they are degraded to the metabolically inert uric acid

which is then excreted from the body. Uric acid is formed when GMP is

split into the base guanine and ribose. Guanine is deaminated to

xanthine which in turn is oxidized to uric acid. This last reaction is

irreversible. Similarly, uric acid can be formed when AMP is deaminated

to IMP from which the ribose unit is removed to form hypoxanthine.

Hypoxanthine is oxidized to xanthine and finally to uric acid. Instead

of uric acid secretion, guanine and IMP can be used for recycling

purposes and nucleic acid synthesis in the presence of PRPP and

aspartate (NH3 donor).

Unnatural base pair (UBP)

An unnatural base pair (UBP) is a designed subunit (or nucleobase) of DNA

which is created in a laboratory and does not occur in nature. In 2012,

a group of American scientists led by Floyd Romesberg, a chemical

biologist at the Scripps Research Institute in San Diego, California, published that his team designed an unnatural base pair (UBP). The two new artificial nucleotides or Unnatural Base Pair (UBP) were named d5SICS and dNaM. More technically, these artificial nucleotides bearing hydrophobic nucleobases, feature two fused aromatic rings that form a (d5SICS–dNaM) complex or base pair in DNA. In 2014 the same team from the Scripps Research Institute reported that they synthesized a stretch of circular DNA known as a plasmid

containing natural T-A and C-G base pairs along with the

best-performing UBP Romesberg's laboratory had designed, and inserted it

into cells of the common bacterium E. coli that successfully replicated the unnatural base pairs through multiple generations. This is the first known example of a living organism passing along an expanded genetic code to subsequent generations. This was in part achieved by the addition of a supportive algal gene that expresses a nucleotide triphosphate transporter which efficiently imports the triphosphates of both d5SICSTP and dNaMTP into E. coli bacteria. Then, the natural bacterial replication pathways use them to accurately replicate the plasmid containing d5SICS–dNaM.

The successful incorporation of a third base pair is a

significant breakthrough toward the goal of greatly expanding the number

of amino acids which can be encoded by DNA, from the existing 21 amino

acids to a theoretically possible 172, thereby expanding the potential

for living organisms to produce novel proteins.

The artificial strings of DNA do not encode for anything yet, but

scientists speculate they could be designed to manufacture new proteins

which could have industrial or pharmaceutical uses.

Length unit

Nucleotide (abbreviated "nt") is a common unit of length for single-stranded nucleic acids, similar to how base pair is a unit of length for double-stranded nucleic acids.

Nucleotide supplements

A

study done by the Department of Sports Science at the University of

Hull in Hull, UK has shown that nucleotides have significant impact on cortisol

levels in saliva. Post exercise, the experimental nucleotide group had

lower cortisol levels in their blood than the control or the placebo.

Additionally, post supplement values of Immunoglobulin A

were significantly higher than either the placebo or the control. The

study concluded, "nucleotide supplementation blunts the response of the

hormones associated with physiological stress."

Another study conducted in 2013 looked at the impact nucleotide

supplementation had on the immune system in athletes. In the study, all

athletes were male and were highly skilled in taekwondo.

Out of the twenty athletes tested, half received a placebo and half

received 480 mg per day of nucleotide supplement. After thirty days, the

study concluded that nucleotide supplementation may counteract the

impairment of the body's immune function after heavy exercise.

Abbreviation codes for degenerate bases

The IUPAC has designated the symbols for nucleotides. Apart from the five (A, G, C, T/U) bases, often degenerate bases are used especially for designing PCR primers.

These nucleotide codes are listed here. Some primer sequences may also

include the character "I", which codes for the non-standard nucleotide inosine.

Inosine occurs in tRNAs, and will pair with adenine, cytosine, or

thymine. This character does not appear in the following table however,

because it does not represent a degeneracy. While inosine can serve a

similar function as the degeneracy "D", it is an actual nucleotide,

rather than a representation of a mix of nucleotides that covers each

possible pairing needed.

| Symbol | Description | Bases represented | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | adenine | A | 1 | |||

| C | cytosine | C | ||||

| G | guanine | G | ||||

| T | thymine | T | ||||

| U | uracil | U | ||||

| W | weak | A | T | 2 | ||

| S | strong | C | G | |||

| M | amino | A | C | |||

| K | keto | G | T | |||

| R | purine | A | G | |||

| Y | pyrimidine | C | T | |||

| B | not A (B comes after A) | C | G | T | 3 | |

| D | not C (D comes after C) | A | G | T | ||

| H | not G (H comes after G) | A | C | T | ||

| V | not T (V comes after T and U) | A | C | G | ||

| N | any base (not a gap) | A | C | G | T | 4 |