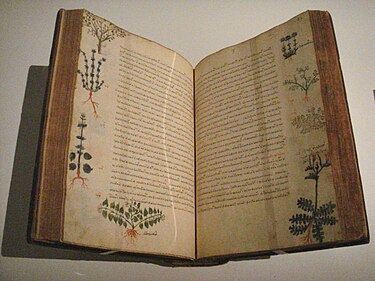

A herbal is a book containing the names and descriptions of plants, usually with information on their medicinal, tonic, culinary, toxic, hallucinatory, aromatic, or magical powers, and the legends associated with them. A herbal may also classify the plants it describes, may give recipes for herbal extracts, tinctures, or potions, and sometimes include mineral and animal medicaments in addition to those obtained from plants. Herbals were often illustrated to assist plant identification.

Herbals were among the first literature produced in Ancient Egypt, China, India, and Europe as the medical wisdom of the day accumulated by herbalists, apothecaries and physicians. Herbals were also among the first books to be printed in both China and Europe. In Western Europe herbals flourished for two centuries following the introduction of moveable type (c. 1470–1670).

In the late 17th century, the rise of modern chemistry, toxicology and pharmacology reduced the medicinal value of the classical herbal. As reference manuals for botanical study and plant identification herbals were supplanted by Floras – systematic accounts of the plants found growing in a particular region, with scientifically accurate botanical descriptions, classification, and illustrations. Herbals have seen a modest revival in the Western world since the last decades of the 20th century, as herbalism and related disciplines (such as homeopathy and aromatherapy) became popular forms of alternative medicine.

History

The word herbal is derived from the mediaeval Latin liber herbalis ("book of herbs"): it is sometimes used in contrast to the word florilegium, which is a treatise on flowers with emphasis on their beauty and enjoyment rather than the herbal emphasis on their utility. Much of the information found in printed herbals arose out of traditional medicine and herbal knowledge that predated the invention of writing.

Before the advent of printing, herbals were produced as manuscripts, which could be kept as scrolls or loose sheets, or bound into codices. Early handwritten herbals were often illustrated with paintings and drawings. Like other manuscript books, herbals were "published" through repeated copying by hand, either by professional scribes or by the readers themselves. In the process of making a copy, the copyist would often translate, expand, adapt, or reorder the content. Most of the original herbals have been lost; many have survived only as later copies (of copies...), and others are known only through references from other texts.

As printing became available, it was promptly used to publish herbals, the first printed matter being known as incunabula. In Europe, the first printed herbal with woodcut (xylograph) illustrations, the Puch der Natur of Konrad of Megenberg, appeared in 1475. Metal-engraved plates were first used in about 1580. As woodcuts and metal engravings could be reproduced indefinitely they were traded among printers: there was therefore a large increase in the number of illustrations together with an improvement in quality and detail but a tendency for repetition.

As examples of some of the world's most important records and first printed matter, a researcher will find herbals scattered through the world's most famous libraries including the Vatican Library in Rome, the Bodleian Library in Oxford, the Royal Library in Windsor, the British Library in London and the major continental libraries.

China, India, Mexico

Shen Nung Pen Ts’ao ching of China

China is renowned for its traditional herbal medicines that date back thousands of years. Legend has it that mythical Emperor Shennong, the founder of Chinese herbal medicine, composed the Shennong Bencao Jing or Great Herbal in about 2700 BCE as the forerunner of all later Chinese herbals. It survives as a copy made c. 500 CE and describes about 365 herbs. High quality herbals and monographs on particular plants were produced in the period to 1250 CE including: the Zhenlei bencao written by Tang Shenwei in 1108, which passed through twelve editions until 1600; a monograph on the lychee by Cai Xiang in 1059 and one on the oranges of Wenzhhou by Han Yanzhi in 1178. In 1406 Ming dynasty prince Zhu Xiao (朱橚) published the Jiuhuang Bencao illustrated herbal for famine foods. It contained high quality woodcuts and descriptions of 414 species of plants of which 276 were described for the first time, the book pre-dating the first European printed book by 69 years. It was reprinted many times. Other herbals include Bencao Fahui in 1450 by Xu Yong and Bencao Gangmu of Li Shizhen in 1590.

Sushruta Samhita of India

Traditional herbal medicine of India, known as Ayurveda, possibly dates back to the second millennium BCE tracing its origins to the holy Hindu Vedas and, in particular, the Atharvaveda. One authentic compilation of teachings is by the surgeon Sushruta, available in a treatise called Sushruta Samhita. This contains 184 chapters and description of 1120 illnesses, 700 medicinal plants, 64 preparations from mineral sources and 57 preparations based on animal sources. Other early works of Ayurveda include the Charaka Samhita, attributed to Charaka. This tradition, however is mostly oral. The earliest surviving written material which contains the works of Sushruta is the Bower Manuscript—dated to the 4th century CE.

Hernandez – Rerum Medicarum and the Aztecs

An illustrated herbal published in Mexico in 1552, Libellus de Medicinalibus Indorum Herbis ("Book of Medicinal Herbs of the Indies"), is written in the Aztec Nauhuatl language by a native physician, Martín Cruz. This is probably an extremely early account of the medicine of the Aztecs although the formal illustrations, resembling European ones, suggest that the artists were following the traditions of their Spanish masters rather than an indigenous style of drawing. In 1570 Francisco Hernández (c.1514–1580) was sent from Spain to study the natural resources of New Spain (now Mexico). Here he drew on indigenous sources, including the extensive botanical gardens that had been established by the Aztecs, to record c. 1200 plants in his Rerum Medicarum of 1615. Nicolás Monardes’ Dos Libros (1569) contains the first published illustration of tobacco.

Egypt, Mesopotamia, Greece and Rome

By about 2000 BCE, medical papyri in ancient Egypt included medical prescriptions based on plant matter and made reference to the herbalist's combination of medicines and magic for healing.[31]

Papyrus Ebers

The ancient Egyptian Papyrus Ebers is one of the earliest known herbals; it dates to 1550 BCE and is based on sources, now lost, dating back a further 500 to 2000 years. The earliest Sumerian herbal dates from about 2500 BCE as a copied manuscript of the 7th century BCE. Inscribed Assyrian tablets dated 668–626 BCE list about 250 vegetable drugs: the tablets include herbal plant names that are still in use today including: saffron, cumin, turmeric and sesame.

The ancient Greeks gleaned much of their medicinal knowledge from Egypt and Mesopotamia. Hippocrates (460–377 BCE), the "father of medicine" (renowned for the eponymous Hippocratic oath), used about 400 drugs, most being of plant origin. However, the first Greek herbal of any note was written by Diocles of Carystus in the fourth century BC—although nothing remains of this except its mention in the written record. It was Aristotle’s pupil Theophrastus (371–287 BCE) in his Historia Plantarum, (better known as the Enquiry into Plants) and De Causis Plantarum (On the Causes of Plants) that established the scientific method of careful and critical observation associated with modern botanical science. Based largely on Aristotle’s notes, the Ninth Book of his Enquiry deals specifically with medicinal herbs and their uses including the recommendations of herbalists and druggists of the day, and his plant descriptions often included their natural habitat and geographic distribution. With the formation of the Alexandrian School c. 330 BCE medicine flourished and written herbals of this period included those of the physicians Herophilus, Mantias, Andreas of Karystos, Appolonius Mys, and Nicander. The work of rhizomatist (the rhizomati were the doctors of the day, berated by Theophrastus for their superstition) Krateuas (fl. 110 BCE) is of special note because he initiated the tradition of the illustrated herbal in the first century BCE.

Dioscorides – De Materia Medica

The De Materia Medica (c. 40–90 CE; Greek, Περί ύλης ιατρικής "Peri hules iatrikes", 'On medical materials') of Pedanios Dioscorides, a physician in the Roman army, was produced in about 65 CE. It was the single greatest classical authority on the subject and the most influential herbal ever written, serving as a model for herbals and pharmacopoeias, both oriental and occidental, for the next 1000 years up to the Renaissance. It drew together much of the accumulated herbal knowledge of the time, including some 500 medicinal plants. The original has been lost but a lavishly illustrated Byzantine copy known as the Vienna Dioscurides dating from about 512 CE remains.

Pliny – Natural History

Pliny the Elder's (23–79 CE) encyclopaedic Natural History (c. 77–79 CE) is a synthesis of the information contained in about 2000 scrolls and it includes myths and folklore; there are about 200 extant copies. It comprises 37 books of which sixteen (Books 12–27) are devoted to trees, plants and medicaments and, of these, seven describe medicinal plants. In medieval herbals, along with De Materia Medica it is Pliny's work that is the most frequently mentioned of the classical texts, even though Galen's (131–201 CE) De Simplicibus is more detailed. Another Latin translation of Greek works that was widely copied in the Middle Ages, probably illustrated in the original, was that attributed to Apuleius: it also contained the alternative names for particular plants given in several languages. It dates to about 400 CE and a surviving copy dates to about 600 CE.

The Middle Ages and Arab World

During the 600 years of the European Middle Ages from 600 to 1200, the tradition of herbal lore fell to the monasteries. Many of the monks were skilled at producing books and manuscripts and tending both medicinal gardens and the sick, but written works of this period simply emulated those of the classical era.

Meanwhile, in the Arab world, by 900 the great Greek herbals had been translated and copies lodged in centres of learning in the Byzantine empire of the eastern Mediterranean including Byzantium, Damascus, Cairo and Baghdad where they were combined with the botanical and pharmacological lore of the Orient. In the medieval Islamic world, Muslim botanists and Muslim physicians made a major contribution to the knowledge of herbal medicines. Those associated with this period include Mesue Maior (Masawaiyh, 777–857) who, in his Opera Medicinalia, synthesised the knowledge of Greeks, Persians, Arabs, Indians and Babylonians, this work was complemented by the medical encyclopaedia of Avicenna (Ibn Sina, 980–1037). Avicenna's Canon of Medicine was used for centuries in both East and West. During this period Islamic science protected classical botanical knowledge that had been ignored in the West and Muslim pharmacy thrived.

Albertus Magnus – De Vegetabilibus

In the thirteenth century, scientific inquiry was returning and this was manifest through the production of encyclopaedias; those noted for their plant content included a seven volume treatise by Albertus Magnus (c. 1193–1280) a Suabian educated at the University of Padua and tutor to St Thomas Aquinas. It was called De Vegetabilibus (c. 1256 AD) and even though based on original observations and plant descriptions it bore a close resemblance to the earlier Greek, Roman and Arabic herbals. Other accounts of the period include De Proprietatibus Rerum (c. 1230–1240) of English Franciscan friar Bartholomaeus Anglicus and a group of herbals called Tractatus de Herbis written and painted between 1280 and 1300 by Matthaeus Platearius at the East-West cultural centre of Salerno Spain, the illustrations showing the fine detail of true botanical illustration.

Western Europe

Perhaps the best known herbals were produced in Europe between 1470 and 1670. The invention in Germany of printing from movable type in a printing press c. 1440 was a great stimulus to herbalism. The new herbals were more detailed with greater general appeal and often with Gothic script and the addition of woodcut illustrations that more closely resembled the plants being described.

Three important herbals, all appearing before 1500, were printed in Mainz, Germany. Two of these were by Peter Schoeffer, his Latin Herbarius in 1484, followed by an updated and enlarged German version in 1485, these being followed in 1491 by the Hortus Sanitatis printed by Jacob Meyderbach. Other early printed herbals include the Kreuterbuch of Hieronymus Tragus from Germany in 1539 and, in England, the New Herball of William Turner in 1551 were arranged, like the classical herbals, either alphabetically, according to their medicinal properties, or as "herbs, shrubs, trees". Arrangement of plants in later herbals such as Cruydboeck of Dodoens and John Gerard's Herball of 1597 became more related to their physical similarities and this heralded the beginnings of scientific classification. By 1640 a herbal had been printed that included about 3800 plants – nearly all the plants of the day that were known.

In the Modern Age and Renaissance, European herbals diversified and innovated, and came to rely more on direct observation than being mere adaptations of traditional models. Typical examples from the period are the fully illustrated De Historia Stirpium Commentarii Insignes by Leonhart Fuchs (1542, with over 400 plants), the astrologically themed Complete Herbal by Nicholas Culpeper (1653), and the Curious Herbal by Elizabeth Blackwell (1737).

Anglo-Saxon herbals

Anglo-Saxon plant knowledge and gardening skills (the garden was called a wyrtzerd, literally, herb-yard) appears to have exceeded that on the continent. Our limited knowledge of Anglo-Saxon plant vernacular comes primarily from manuscripts that include: the Leechbook of Bald and the Lacnunga. The Leechbook of Bald (Bald was probably a friend of King Alfred of England) was painstakingly produced by the scribe Cild in about 900–950 CE. This was written in the vernacular (native) tongue and not derived from Greek texts. The oldest illustrated herbal from Saxon times is a translation of the Latin Herbarius Apulei Platonici, one of the most popular medical works of medieval times, the original dating from the fifth century; this Saxon translation was produced about 1000–1050 CE and is housed in the British Library. Another vernacular herbal was the Buch der natur or "Book of Nature" by Konrad von Megenberg (1309–1374) which contains the first two botanical woodcuts ever made; it is also the first work of its kind in the vernacular.

Anglo-Norman herbals

In the 12th and early 13th centuries, under the influence of the Norman conquest, the herbals produced in Britain fell less under the influence of France and Germany and more that of Sicily and the Near East. This showed itself through the Byzantine-influenced Romanesque framed illustrations. Anglo-Saxon herbals in the vernacular were replaced by herbals in Latin including Macers Herbal, De Viribus Herbarum (largely derived from Pliny), with the English translation completed in about 1373.

Fifteenth-century incunabula

The earliest printed books and broadsheets are known as incunabula. The first printed herbal appeared in 1469, a version of Pliny's Historia Naturalis; it was published nine years before Dioscorides De Materia Medica was set in type. Important incunabula include the encyclopaedic De Proprietatibus Rerum of Franciscan friar Bartholomew Anglicus (c. 1203–1272) which, as a manuscript, had first appeared between 1248 and 1260 in at least six languages and after being first printed in 1470 ran to 25 editions. Assyrian physician Mesue (926–1016) wrote the popular De Simplicibus, Grabadin and Liber Medicinarum Particularum the first of his printings being in 1471. These were followed, in Italy, by the Herbarium of Apuleius Platonicus and three German works published in Mainz, the Latin Herbarius (1484), the first herbal published in Germany, German Herbarius (1485), the latter evolving into the Ortus Sanitatis (1491). To these can be added Macer’s De Virtutibus Herbarum, based on Pliny's work; the 1477 edition is one of the first printed and illustrated herbals.

Fifteenth-century manuscripts

In medieval times, medicinal herbs were generally referred to by the apothecaries (physicians or doctors) as "simples" or "officinals". Before 1542, the works principally used by apothecaries were the treatises on simples by Avicenna and Serapion’s Liber De Simplici Medicina. The De Synonymis and other publications of Simon Januensis, the Liber Servitoris of Bulchasim Ben Aberazerim, which described the preparations made from plants, animals and minerals, provided a model for the chemical treatment of modern pharmacopoeias. There was also the Antidotarium Nicolai of Nicolaus de Salerno, which contained Galenical compounds arranged in alphabetical order.

Spain and Portugal – de Orta, Monardes, Hernandez

The Spaniards and Portuguese were explorers, the Portuguese to India (Vasco da Gama) and Goa where physician Garcia de Orta (1490–1570) based his work Coloquios dos Simples (1563). The first botanical knowledge of the New World came from Spaniard Nicolas Monardes (1493–1588) who published Dos Libros between 1569 and 1571. The work of Hernandez on the herbal medicine of the Aztecs has already been discussed.

Germany – Bock, Brunfels and Fuchs

Otto Brunfels (c. 1489–1534), Leonhart Fuchs (1501–1566) and Hieronymus Bock (1498–1554) were known as the "German fathers of botany" although this title belies the fact that they trod in the steps of the scientifically feted Hildegard of Bingen whose writings on herbalism were Physica and Causae et Curae (together known as Liber subtilatum) of 1150. The original manuscript is no longer in existence but a copy was printed in 1533. Another major herbalist was Valerius Cordus (1515–1544).

The 1530, Herbarum Vivae Eicones of Brunfels contained the admired botanically accurate original woodcut colour illustrations of Hans Weiditz along with descriptions of 47 species new to science. Bock, in setting out to describe the plants of his native Germany, produced the New Kreuterbuch of 1539 describing the plants he had found in the woods and fields but without illustration; this was supplemented by a second edition in 1546 that contained 365 woodcuts. Bock was possibly the first to adopt a botanical classification in his herbal which also covered details of ecology and plant communities. In this, he was placing emphasis on botanical rather than medicinal characteristics, unlike the other German herbals and foreshadowing the modern Flora. De Historia Stirpium (1542 with a German version in 1843) of Fuchs was a later publication with 509 high quality woodcuts that again paid close attention to botanical detail: it included many plants introduced to Germany in the sixteenth century that were new to science. The work of Fuchs is regarded as being among the most accomplished of the Renaissance period.

Low Countries – Dodoens, Lobel, Clusius

The Flemish printer Christopher Plantin established a reputation publishing the works of Dutch herbalists Rembert Dodoens and Carolus Clusius and developing a vast library of illustrations. Translations of early Greco-Roman texts published in German by Bock in 1546 as Kreuterbuch were subsequently translated into Dutch as Pemptades by Dodoens (1517–1585) who was a Belgian botanist of world renown. This was an elaboration of his first publication Cruydeboeck (1554). Matthias de Lobel (1538–1616) published his Stirpium Adversaria Nova (1570–1571) and a massive compilation of illustrations while Clusius's (1526–1609) magnum opus was Rariorum Plantarum Historia of 1601 which was a compilation of his Spanish and Hungarian floras and included over 600 plants that were new to science.

Italy – Mattioli, Calzolari, Alpino

In Italy, two herbals were beginning to include botanical descriptions. Notable herbalists included Pietro Andrea Mattioli (1501–1577), physician to the Italian aristocracy and his Commentarii (1544), which included many newly described species, and his more traditional herbal Epistolarum Medicinalium Libri Quinque (1561). Sometimes, the local flora was described as in the publication Viaggio di Monte Baldo (1566) of Francisco Calzolari. Prospero Alpini (1553–1617) published in 1592 the highly popular account of overseas plants De Plantis Aegypti and he also established a botanical garden in Padua in 1542, which together with those at Pisa and Florence, rank among the world's first.

England – Turner, Gerard, Parkinson, Culpeper

The first true herbal printed in Britain was Richard Banckes' Herball of 1525 which, although popular in its day, was unillustrated and soon eclipsed by the most famous of the early printed herbals, Peter Treveris's Grete Herball of 1526 (derived in turn from the derivative French Grand Herbier).

William Turner (?1508–7 to 1568) was an English naturalist, botanist, and theologian who studied at Cambridge University and eventually became known as the “father of English botany." His 1538 publication Libellus de re Herbaria Novus was the first essay on scientific botany in English. His three-part A New Herball of 1551–1562–1568, with woodcut illustrations taken from Fuchs, was noted for its original contributions and extensive medicinal content; it was also more accessible to readers, being written in vernacular English. Turner described over 200 species native to England. and his work had a strong influence on later eminent botanists such as John Ray and Jean Bauhin.

John Gerard (1545–1612) is the most famous of all the English herbalists. His Herball of 1597 is, like most herbals, largely derivative. It appears to be a reformulation of Hieronymus Bock's Kreuterbuch subsequently translated into Dutch as Pemptades by Rembert Dodoens (1517–1585), and thence into English by Carolus Clusius, (1526–1609) then re-worked by Henry Lyte in 1578 as A Nievve Herball. This became the basis of Gerard's Herball or General Historie of Plantes. that appeared in 1597 with its 1800 woodcuts (only 16 original). Although largely derivative, Gerard's popularity can be attributed to his evocation of plants and places in Elizabethan England and to the clear influence of gardens and gardening on this work. He had published, in 1596, Catalogus which was a list of 1033 plants growing in his garden.

John Parkinson (1567–1650) was apothecary to James I and a founding member of the Worshipful Society of Apothecaries. He was an enthusiastic and skilful gardener, his garden in Long Acre being stocked with rarities. He maintained an active correspondence with important English and Continental botanists, herbalists and plantsmen importing new and unusual plants from overseas, in particular the Levant and Virginia. Parkinson is celebrated for his two monumental works, the first Paradisi in Sole Paradisus Terrestris in 1629: this was essentially a gardening book, a florilegium for which Charles I awarded him the title Botanicus Regius Primarius – Royal Botanist. The second was his Theatrum Botanicum of 1640, the largest herbal ever produced in the English language. It lacked the quality illustrations of Gerard's works, but was a massive and informative compendium including about 3800 plants (twice the number of Gerard's first edition Herball), over 1750 pages and over 2,700 woodcuts. This was effectively the last and culminating herbal of its kind and, although it included more plants of no discernible economic or medicinal use than ever before, they were nevertheless arranged according to their properties rather than their natural affinities.

Nicholas Culpeper (1616–1654) was an English botanist, herbalist, physician, apothecary and astrologer from London's East End. His published books were A Physicall Directory (1649), which was a pseudoscientific pharmacopoeia. The English Physitian (1652) and the Complete Herbal (1653), contain a rich store of pharmaceutical and herbal knowledge. His works lacked scientific credibility because of their use of astrology, though he combined diseases, plants and astrological prognosis into a simple integrated system that has proved popular to the present day.

Legacy

The legacy of the herbal extends beyond medicine to botany and horticulture. Herbal medicine is still practiced in many parts of the world but the traditional grand herbal, as described here, ended with the European Renaissance, the rise of modern medicine and the use of synthetic and industrialized drugs. The medicinal component of herbals has developed in several ways. Firstly, discussion of plant lore was reduced and with the increased medical content there emerged the official pharmacopoeia. The first British Pharmacopoeia was published in the English language in 1864, but gave such general dissatisfaction both to the medical profession and to chemists and druggists that the General Medical Council brought out a new and amended edition in 1867. Secondly, at a more popular level, there are the books on culinary herbs and herb gardens, medicinal and useful plants. Finally, the enduring desire for simple medicinal information on specific plants has resulted in contemporary herbals that echo the herbals of the past, an example being Maud Grieve's A Modern Herbal, first published in 1931 but with many subsequent editions.

The magical and mystical side of the herbal also lives on. Herbals often explained plant lore, displaying a superstitious or spiritual side. There was, for example, the fanciful doctrine of signatures, the belief that there were similarities in the appearance of the part of the body affected the appearance of the plant to be used as a remedy. The astrology of Culpeper can be seen in contemporary anthroposophy (biodynamic gardening) and alternative medical approaches like homeopathy, aromatherapy and other new age medicine show connections with herbals and traditional medicine.

It is sometimes forgotten that the plants described in herbals were grown in special herb gardens (physic gardens). Such herb gardens were, for example, part of the medieval monastery garden that supplied the simples or officinals used to treat the sick being cared for within the monastery. Early physic gardens were also associated with institutes of learning, whether a monastery, university or herbarium. It was this medieval garden of the fourteenth to sixteenth centuries, attended by apothecaries and physicians, that established a tradition leading to the systems gardens of the eighteenth century (gardens that demonstrated the classification system of plants) and the modern botanical garden. The advent of printing, woodcuts and metal engraving improved the means of communication. Herbals prepared the ground for modern botanical science by pioneering plant description, classification and illustration. From the time of the ancients like Dioscorides through to Parkinson in 1629, the scope of the herbal remained essentially the same.

The greatest legacy of the herbal is to botany. Up to the seventeenth century, botany and medicine were one and the same but gradually greater emphasis was placed on the plants rather than their medicinal properties. During the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, plant description and classification began to relate plants to one another and not to man. This was the first glimpse of non-anthropocentric botanical science since Theophrastus and, coupled with the new system of binomial nomenclature, resulted in "scientific herbals" called Floras that detailed and illustrated the plants growing in a particular region. These books were often backed by herbaria, collections of dried plants that verified the plant descriptions given in the Floras. In this way modern botany, especially plant taxonomy, was born out of medicine. As herbal historian Agnes Arber remarks – "Sibthorp's monumental Flora Graeca is, indeed, the direct descendant in modern science of the De Materia Medica of Dioscorides."

![Red-hot shell containing plutonium undergoing nuclear decay, inside the Mars Science Laboratory MMRTG.[27] MSL was launched in 2011 and landed on Mars in August 2012.](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/2/23/Fueling_of_the_MSL_MMRTG_001.jpg/448px-Fueling_of_the_MSL_MMRTG_001.jpg)