Concentration of media ownership (also known as media consolidation or media convergence) is a process whereby progressively fewer individuals or organizations control increasing shares of the mass media. Contemporary research demonstrates increasing levels of consolidation, with many media industries already highly concentrated and dominated by a very small number of firms.

Globally, large media conglomerates include Bertelsmann, National Amusements (Paramount Global), Sony Group Corporation, News Corp, Comcast, The Walt Disney Company, Warner Bros. Discovery, Fox Corporation, Hearst Communications, MGM Holdings Inc., Grupo Globo (South America), and Lagardère Group.

As of 2022, the largest media conglomerates in terms of revenue are Comcast, The Walt Disney Company, Warner Bros. Discovery, and Paramount Global.

Mergers

Media mergers occur when one media company buys another. The current landscape of corporate media ownership in the United States of America can be described as an oligopoly.

Risks for media integrity

Media integrity is at risk when small number of companies and individuals control the media market. Media integrity refers to the ability of a media outlet to serve the public interest and democratic process, making it resilient to institutional corruption within the media system, economy of influence, conflicting dependence and political clientelism.

Elimination of net neutrality

Net neutrality is also at stake when media mergers occur. Net neutrality involves a lack of restrictions on content on the internet, however, with big businesses supporting campaigns financially they tend to have influence over political issues, which can translate into their mediums. These big businesses that also have control over internet usage or the airwaves could possibly make the content available biased from their political stand point or they could restrict usage for conflicting political views, therefore eliminating net neutrality.

Issues

Concentration of media ownership is very frequently seen as a problem of contemporary media and society.

Freedom of the press and editorial independence

Johannes von Dohnanyi, in a 2003 report published by the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe (OSCE)'s Office of the Representative on Freedom of the Media, argued market concentration among media—whether driven by domestic or foreign investors—should be "closely monitored" because "Horizontal concentration may cause dangers to media pluralism and diversity, while vertical concentration may result in entry barriers for new competitors." Von Dohnanyi argues that to "safeguard free and independent print media and protect professional journalism as one of the cornerstones of constitutional democracy" there should be standards for editorial independence, better labor protections for professional journalists, and independent institutions "to monitor the implementation and observance of all laws and regulations regarding concentration processes, media pluralism, content diversity and journalistic freedoms."

Deregulation

Robert W. McChesney argues that the concentration of media ownership is caused by a shift to neoliberal deregulation policies, which is a market-driven approach. Deregulation effectively removes governmental barriers to allow for the commercial exploitation of media. Motivation for media firms to merge includes increased profit-margins, reduced risk and maintaining a competitive edge. In contrast to this, those who support deregulation have argued that cultural trade barriers and regulations harm consumers and domestic support in the form of subsidies hinders countries to develop their own strong media firms. The opening of borders is more beneficial to countries than maintaining protectionist regulations.

Critics of media deregulation and the resulting concentration of ownership fear that such trends will only continue to reduce the diversity of information provided, as well as to reduce the accountability of information providers to the public. The ultimate consequence of consolidation, critics argue, is a poorly informed public, restricted to a reduced array of media options that offer only information that does not harm the media oligopoly's growing range of interests.

For those critics, media deregulation is a dangerous trend, facilitating an increase in concentration of media ownership, and subsequently reducing the overall quality and diversity of information communicated through major media channels. Increased concentration of media ownership can lead to corporate censorship affecting a wide range of critical thought.

Media pluralism

The concentration of media ownership is commonly regarded as one of the crucial aspects reducing media pluralism. A high concentration of the media market increases the chances to reduce the plurality of political, cultural and social points of views. Even if ownership of the media is one of the main concerns when it comes to assessing media pluralism, the concept of media pluralism is broader as it touches many aspects, from merger control rules to editorial freedom, the status of public service broadcasters, the working conditions of journalists, the relationship between media and politics, representation of local and regional communities and the inclusion of minorities' voices. Also, it embraces all measures guaranteeing citizens' access to diversified sources so to allow the formation of a plurality of opinions in the public sphere without undue influence of dominant powers.

Furthermore, media pluralism has a two-fold dimension, or rather internal and external. Internal pluralism concerns pluralism within a specific media organisation: in this regard, many countries request public broadcast services to account for a variety of views and opinions, including those of minority groups. External pluralism applies instead to the overall media landscape, for instance in terms of the number of media outlets operating in a given country.

Media ownership can pose serious challenges to pluralism when owners interfere with journalists' independence and editorial line. However, in a free market economy, owners must have the capacity to decide the strategy of their company to remain competitive in the market. Also, pluralism does not mean neutrality and lack of opinion, as having an editorial line is an integral part of the role of editors provided that this line is transparent and explicit to both the staff and audience.

Determinants of media pluralism

Size and wealth of the market

"Within any free market economy, the level of resources available for the provision of media will be constrained principally by the size and wealth of that economy, and the propensity of its inhabitants to consume media." [Gillian Doyle; 2002:15] Those countries that have a relatively large market, like the United Kingdom, France or Spain have more financial background to support diversity of output and have the ability to keep more media companies in the market (as they are there to make profit). More diverse output and fragmented ownership will, obviously, support pluralism. In contrast, small markets like Ireland or Hungary suffer from the absence of the diversity of output given in countries with bigger markets. It means that "support for the media through direct payment" and "levels of consumers expenditure", furthermore "the availability of advertising support" [Gillian Doyle; 2002:15] are less in these countries, due to the low number of audience. Overall, the size and wealth of the market determine the diversity of both media output and media ownership.

Consolidation of resources

The consolidation of cost functions and cost-sharing. Cost-sharing is a common practice in monomedia and cross media. For example, "for multi-product television or radio broadcasters, the more homogeneity possible between different services held in common ownership (or the more elements within a programme schedule which can be shared between 'different' stations), the greater the opportunity to reap economies". Though the main concern of pluralism is that different organization under different ownership may buy the same e.g. news stories from the same news-supplier agency. In the UK, the biggest news-supplier is The Press Association (PA). Here is a quoted text from PA web site: "The Press Association supplies services to every national and regional daily newspaper, major broadcasters, online publishers and a wide range of commercial organisations." Overall, in a system where all different media organizations gather their stories from the same source, we can't really call that system pluralist. That is where diversity of output comes in.

Pluralism in media ownership

Media privatization and the lessening of state dominance over media content has continued since 2012. In the Arab region, the Arab States Broadcasting Union (ASBU) counted 1,230 television stations broadcasting via Arab and international satellites, of which 133 were state-owned and 1,097 private. According to the ASBU Report, these numbers serve as evidence of a decline in the percentage of state channels and a rise in national private and foreign public stations targeting the Arab region. The reduction of direct government ownership over the whole media sector is commonly registered as a positive trend, but this has paralleled by a growth in outlets with a sectarian agenda.

In Africa, some private media outlets have maintained close ties to governments or individual politicians, while media houses owned by politically non-aligned individuals have struggled to survive, often in the face of advertising boycotts by state agencies. In almost all regions, models of public service broadcasting have been struggling for funding. In Western, Central and Eastern Europe, funds directed to public service broadcasting have been stagnating or declining since 2012.

New types of cross-ownership have emerged in the past five years that have spurred new questions about where to draw the line between media and other industries. A notable case has been the acquisition of The Washington Post by the founder of online retailer Amazon. While the move initially raised concerns about the newspaper's independence, the newspaper has significantly increased its standing in the online media—and print—and introduced significant innovations.

The community-centred media ownership model continues to survive in some areas, especially in isolated, rural or disadvantaged areas, and mostly pertaining to radio. Through this model, not-for-profit media outlets are run and managed by the communities they serve.

In particular nations

Australia

Controls over media ownership in Australia are laid down in the Broadcasting Services Act 1992, administered by the Australian Communications and Media Authority (ACMA). Even with laws in place Australia has a high concentration of media ownership. Ownership of national and the newspapers of each capital city are dominated by two corporations, Rupert Murdoch's News Corp Australia, (which was founded in Adelaide as News Limited) and Nine Entertainment Co. These two corporations along with Seven West Media co-own Australian Associated Press which distributes the news and then sells it on to other outlets such as the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Although much of the everyday mainstream news is drawn from the Australian Associated Press, all the privately owned media outlets still compete with each other for exclusive pop culture news. Rural and regional media is dominated by Australian Community Media, with significant holdings in all states and territories. Daily Mail and General Trust operate the DMG Radio Australia commercial radio networks in metropolitan and regional areas of Australia. Formed in 1996, it has since become one of the largest radio media companies in the country. The company currently own more than 60 radio stations across New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, Queensland and Western Australia.

There are rules governing foreign ownership of Australian media and these rules were loosened by the former Howard Government.

Media Watch is an independent media watchdog televised on the public broadcaster Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC), which is one of two government-administered channels, the other being Special Broadcasting Service (SBS).

In late 2011, the Finkelstein Inquiry into media regulation was launched, and reported its findings back to the federal government in early 2012.

New Zealand

Independent Newspapers Limited (INL) formerly published the Wellington-based newspapers The Dominion and The Evening Post, in addition to purchasing a large shareholding in pay TV broadcaster Sky Media Limited in 1997. These two newspapers merged to form the Dominion Post in 2002, and in 2003, sold its entire print media division to Fairfax New Zealand. The remainder of the company officially merged with Sky Media Limited in 2005 to form Sky Network Television Limited.

When INL ceased publishing the Auckland Star in 1991, The New Zealand Herald became the Auckland region's sole daily newspaper. The New Zealand Herald and the New Zealand Listener, formerly privately held by the Wilson & Horton families, was sold to APN News & Media in 1996. The long-running news syndication agency NZPA announced that it would close down in 2011, with operations to be taken over by 3 separate agencies, APN's APNZ, Fairfax's FNZN and AAP's NZN, all owned by Australian parent companies. In 2014, APN's New Zealand division officially changed its name to NZME, in order to reflect the company's convergence with its radio division The Radio Network. As of early 2015, Fairfax New Zealand and NZME have a near duopoly on newspapers and magazines in New Zealand. In May 2016, NZME and Fairfax NZ announced merger talks, pending Commerce Commission approval.

Commercial radio stations are largely divided up between MediaWorks New Zealand and NZME, with MediaWorks also owning TV3 and C4 (now The Edge TV). Television New Zealand, although 100% state-owned, has been run on an almost entirely commercial basis since the late 1980s, in spite of previous attempts to steer it towards a more public service-oriented role. Its primary public-service outlet, TVNZ7, ceased broadcasting in 2012 due to non-renewal of funding, and the youth-oriented TVNZ6 was rebranded as the short-lived commercial channel TVNZ U. In addition, the TVNZ channels Kidzone (and formerly TVNZ Heartland) are only available through Sky Network Television and not on the Freeview platform.

Sky Network Television has had an effective monopoly on pay TV in New Zealand since its nearest rival Saturn Communications (later part of TelstraClear and now Vodafone New Zealand) began wholesaling Sky content in 2002. However, in 2011, TelstraClear CEO Allan Freeth warned it would review its wholesale agreement with Sky unless it allowed TelstraClear to purchase non-Sky content.

Canada

Canada has the biggest concentrated TV ownership out of all the G8 countries and it comes in second place for the most concentrated television viewers.

Broadcasting and telecommunications in Canada are regulated by the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC), an independent governing agency that aims to serve the needs and interests of citizens, industries, interest groups and the government. The CRTC does not regulate newspapers or magazines.

Apart from a relatively small number of community broadcasters, media in Canada are primarily owned by a small number of groups, including Bell Canada, the Shaw family (via Corus Entertainment and Shaw Communications), Rogers Communications, Quebecor, and the government-owned CBC/Radio-Canada. Each of these companies holds a diverse mix of television, specialty television, and radio operations. Bell, Rogers, Shaw, and Quebecor also engage in the telecommunications industry with their ownership of internet providers, television providers, and mobile carriers, while Rogers is also involved in publishing.

In 2007, CTVglobemedia, Rogers Media and Quebecor all expanded significantly through the acquisitions of CHUM Limited, CityTV and Osprey Media, respectively. In 2010, Canwest Global Communications, having filed for bankruptcy, sold its television assets to Shaw (through a new subsidiary, Shaw Media) and spun off its newspaper holdings into Postmedia Network, a new company founded by the National Post's CEO Paul Godfrey. Later that year, Bell also announced that it would acquire the remaining shares of CTVglobemedia (which was originally majority owned by Bell when it was formed in 2001; Bell had reduced its stake in the following years), forming Bell Media.

Between 1990 and 2005 there were a number of media corporate mergers and takeovers in Canada. For example, in 1990, 17.3% of daily newspapers were independently owned; whereas in 2005, 1% were. These changes, among others, caused the Senate Standing Committee on Transport and Communications to launch a study of Canadian news media in March 2003. (This topic had been examined twice in the past, by the Davey Commission (1970) and the Kent Commission (1981), both of which produced recommendations that were never implemented in any meaningful way.)

The Senate Committee's final report, released in June 2006, expressed concern about the effects of the current levels of news media ownership in Canada. Specifically, the committee discussed their concerns regarding the following trends: the potential of media ownership concentration to limit news diversity and reduce news quality; the CRTC and Competition Bureau's ineffectiveness at stopping media ownership concentration; the lack of federal funding for the CBC and the broadcaster's uncertain mandate and role; diminishing employment standards for journalists (including less job security, less journalistic freedom, and new contractual threats to intellectual property); a lack of Canadian training and research institutes; and difficulties with the federal government's support for print media and the absence of funding for the internet-based news media.

The Senate report expressed particular concern about the concentration of ownership in the province of New Brunswick, where the Irving business empire owns all the English-language daily newspapers and most of the weeklies. Senator Joan Fraser, author of the report, stated, "We didn't find anywhere else in the developed world a situation like the situation in New Brunswick."

The report provided 40 recommendations and 10 suggestions (for areas outside of federal government jurisdiction), including legislation amendments that would trigger automatic reviews of a proposed media merger if certain thresholds are reached, and CRTC regulation revisions to ensure that access to the broadcasting system is encouraged and that a diversity of news and information programming is available through these services.

Public inquires into the concentration of ownership and its impact upon democracy. The Canadian regulatory framework imposes requirements upon the protection and enhancement of Canadian culture (through regulation, subsidies and the operation of the CBC). Increasing acceptance of media/news as commercial enterprise in 1990s driven by: hegemony of new-liberalism, role of commodified information technology in economic growth, commitment to private sector "champions" of Canadian culture.

Brazil

In Brazil, the concentration of media ownership seems to have manifested itself very early. Dr. Venício A. de Lima noted in 2003:

in Brazil there is an environment very conducive to concentration. Sectorial legislation has been timid, by express intention of the legislator, by failing to include direct provisions that limit or control the concentration of ownership, which, incidentally, goes in the opposite direction of what happens in countries like France, Italy and the United Kingdom, which are concerned with the plurality and diversity in the new scenario of technological convergence.

— Lobato, Folha de S.Paulo, 10/14/2001

Lima points to other factors that would make media concentration easier, particularly in broadcasting: the failure of legal norms that limit the equity interest of the same economic group in various broadcasting organizations; a short period (five years) for resell broadcasting concessions, facilitating the concentration by the big media groups through the purchase of independent stations, and no restrictions to the formation of national broadcasting networks. He cites examples of horizontal, vertical, crossed and "in cross" concentration (a Brazilian peculiarity).

- Horizontal concentration: oligopoly or monopoly produced within an area or industry; television (pay or free) is the Brazilian classical model. In 2002 the cable networks Sky and NET dominated 61% of the Brazilian market. In the same year, 58.37% of all advertising budgets were invested in TV – and in this aspect, TV Globo and its affiliates received 78% of the amount.

- Vertical concentration: integration of the different phases of production and distribution, eliminating the work of independent producers. In Brazil, unlike the United States, it is common for a TV network to produce, advertise, market and distribute most of its programming. TV Globo is known for its soap operas exported to dozens of countries; it keeps under permanent contract the actors, authors, and the whole production staff. The final product is broadcast by a network of newspapers, magazines, radio stations and websites owned by Globo Organizations.

- Cross ownership: ownership of different kinds of media (TV, newspapers, magazines, etc.) by the same group. Initially, the phenomenon occurred in radio, television and print media, with emphasis on the group of "Diários Associados." At a later stage appeared the RBS Group (affiliated to TV Globo), with operations in the markets of Rio Grande do Sul and Santa Catarina. Besides being the owner of radio and television stations, and of the main local newspapers, it has two Internet portals. The opinions of its commentators are thus replicated by a multimedia system that makes it extremely easy to spread the point of view advocated by the group.

- Monopoly "in cross": reproduction into local level, of the particularities of cross ownership. Research carried out in the early 1990s, detected the presence of this singularity in 18 of the 26 Brazilian states. Manifests itself by the presence of a TV channel with a large audience, often linked to TV Globo and by the existence of two daily newspapers, in which the one with the largest circulation is linked to the major television channel and to a network of radio stations, that almost always reproduces articles and the editorial line of the newspaper "O Globo". In 2002, another survey (which did not include pay TV), found the presence of the "monopoly in cross" in 13 major markets in Brazil.

The UNESCO office in Brasília has expressed its concern over the existence of an outdated code of telecommunications (1962), which no longer meets the expectations generated by the Brazilian Constitution of 1988 in the political and social fields, and the inability of the Brazilian government to establish an independent regulatory agency to manage the media. Attempts in this direction have been pointed by the mainstream media as attacks on freedom of expression, the trend of the political left in the entire Latin American continent.

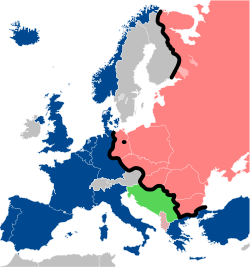

Europe

Council of Europe and European Union

Since the 1980, a significant debate has developed at the European level concerning the regulation of media ownership and the principles to be adopted to regulate media ownership concentration. Both the Council of Europe (CoE) and the European Union (EU) have tried to formulate a distinctive and comprehensive media policy, including on the issue of concentration. However, the emphasis of both the organisations was more on strengthening media diversity and pluralism than on limiting concentration, even though they have often expressed the need for common European media concentration regulations. However, the European Union enforces a common regulation for environmental protection, consumer protection and human rights, but it has none for media pluralism.

Although there is no specific media concentration legislation at the European level, a number of existing legal instruments such as the Amsterdam Protocol, the Audiovisual Media Services Directive and actions programs contribute directly and indirectly to curbing media concentration at EU level.

When it comes to regulating media concentration at the common European level, there is a conflict between Member states and the European Commission (EC). Even if Member states do not publicly challenge the need for common regulation on media concentration, they push to incorporate their own regulatory approach at the EU level and are reluctant to give the European Union their regulatory power on the issue of media concentration.

The Council of Europe's initiative promoting media pluralism and curbing media concentration dates back to the mid-1970s. Several resolutions, recommendations, declarations by the Council of Europe Committee of Ministers and studies by experts' groups have addressed the issue since then. The council's approach has been mainly addressed at defining and protecting media pluralism, defined in terms of pluralism of media content in order to allow a plurality of ideas and opinions.

Within the European Union, two main standpoints have emerged in the debate: on the one hand, the European Parliament has favoured the idea that, considering the crucial role that media play in the functioning of democratic systems, policies in this field should prevent excessive concentration in order to guarantee pluralism and diversity. On the other hand, the European Commission has privileged the understanding that the media sector should be regulated, as any other economic field, following the principles of market harmonization and liberalization.

Indeed, media concentration issues can be addressed both by general competition policies and by specific media sector rules. According to some scholars, given the vital importance of contemporary media, sector-specific competition rules in the media industries should be enhanced. Within the EU, the Council regulation 4064/89/EEC on the control of concentrations between undertakings as part of European competition legislation covered also media concentration cases. The need for sector-specific regulation has been widely supported by both media scholars and the European Parliament. In the 1980s, when preparing legislation on cross-border television many experts and MEPs argued for including provisions for media concentration in the EU directive but these efforts failed. In 1992, the Commission of the European Communities published a policy document named "Pluralism and Media Concentration in the internal Market – an assessment of the need for Community action" which outlined three options on the issue of media concentration regulation at the Community level, i.e. no specific action to be taken; action regulating transparency; and action to harmonize laws. Out of these options, the first one was chosen but the debate on this decision lasted for years. Council regulation as a tool for regulating media concentration was excluded and the two proposals on a media concentration directive advanced in the mid 1990s were not backed by the commission. As a consequence, efforts at legislating media concentration at Community level were phased out by the end of the 1990s.

Despite a wide consensus over the idea that the vital importance of contemporary media justifies to regulate media concentration through sector-specific concentration rules going beyond the general competition policy, the need for sector specific regulation has been challenged in recent years due to the peculiar evolution of the media industry in the digital environment and media convergence. In practice, sector-specific media concentration rules have been abolished in some European countries in recent years.

As a consequence, scholars Harcourt and Picard argue that "the trend has been to remove ownership rules and restrictions on media ownership within Europe in order that 'domestic champions' can bulk up to 'fend off' the US threat. This has been a key argument for the loosening of ownership rules within Europe."

In 2002, the European Parliament tried to revitalize the efforts on regulating media concentration at the European level and adopted a resolution on media concentration which called on the European Commission to launch a broad and comprehensive consultation on media pluralism and media concentration and to prepare a Green Paper on the issue by the end of 2003. The European Commission failed to meet this deadline. In the following years, during the process of amending the Televisions Without Frontiers directive, which was adopted by the EP and the Council in 2007, the issue of media concentration was discussed, but it did not represent the core of the debate. In 2003, the European Commission issued a policy document named "The future of European Regulatory Audiovisual Policy" which stressed that, in order to ensure media pluralism, measures should aim at limiting the level of media concentration by establishing "maximum holdings in media companies and prevent[ing] cumulative control or participation in several media companies at the same time".

In 2007, reacting to concerns on media concentration and its repercussion on pluralism and freedom of expression in the EU member states raised by the European Parliament and by NGOs, the European Commission launched a new three-phase plan on media pluralism.

In October 2009, a European Union Directive was proposed to set for all member states common and higher standards for media pluralism and freedom of expression. The proposal was put to a vote in the European Parliament and rejected by just three votes. The directive was supported by the liberal-centrists, the progressives and the greens, and was opposed by the European People's Party. Unexpectedly, the Irish liberals made an exception by voting against the directive, and later revealed that they had been pressured by the Irish right-wing government to do so.

Following this debate, the European Commission commissioned a large, in depth study published in 2009 aiming to identify the indicators to be adopted to assess media pluralism in Europe.

The "Independent Study on Indicators for Media Pluralism in the Member States – Towards a Risk-Based Approach" provided a prototype of indicators and country reports for 27 EU member states. After years of refining and preliminary testings, the study resulted in the Media Pluralism Monitor (MPM), a yearly monitoring carried out by the Centre for Media Pluralism and Freedom at the European University Institute in Florence on a variety of aspects affecting media pluralism, including also the concentration of media ownership is considered. To assess the risk that media ownership concentration in a given country may actually hinder media pluralism, the MPM takes into account three specific elements:

- Horizontal concentration, that is concentration of media ownership within a given media sector (press, audio-visual, etc.);

- Cross-media concentration across different media markets;

- Transparency of media ownership.

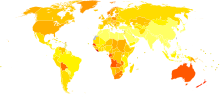

In 2015, the MPM was carried out in 19 European countries. The results of the monitoring activity in the field of media market concentration identify five countries as facing a high risk: Finland, Luxembourg, Lithuania, Poland and Spain. There are nine countries facing a medium risk: Czech Republic, Germany, Ireland, Latvia, Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Sweden. Finally, only five countries face a low risk: Croatia, Cyprus, Malta, Slovenia and Slovakia. In the monitoring carried out in 2014, 7 of 9 countries (Belgium, Bulgaria, Denmark, France, Hungary, Italy, the UK) scored a high risk in audience concentration.

Pan-European groups

A 2016 report based on data collected by MAVISE, a free online database on audiovisual services and companies in Europe, highlights the growing number of Pan-European media companies in the field of broadcasting and divides them into different categories: multi‐country media groups, controlling "channels that play an important role in various national markets (for example Modern Times Group, CEME, RTL, a Luxembourg-based media group operating in 10 countries, and Sanoma). These groups generally control a high market share in the countries in which they operate, and have gradually emerged through the acquisition of existing channels or by establishing new companies in countries in which they were not already present. The four groups RTL Group, CEME, Modern Times Group and Sanoma are major players (in the top 4 regarding audience share) in 19 European countries (RTL Group, CEME and Modern Times Group are major players in 17 countries). Pan‐European broadcasters operate with a unique identity and well recognized brands across Europe. Most of them are based in the United States and have progressively expanded their activities in the European market. In many cases, these groups evolved from being content creators to also deliver such contents through channels renamed after the original brands.

Examples of such pan-European groups include Warner Bros. Discovery, Paramount Global, and The Walt Disney Company, pan‐European distribution groups (cable and satellite operators), companies that operate at the European level in the distribution sector via cable, satellite or IPTV. The emergence of major actors operating in this field has been made possible mainly thanks to the process of digitalization and benefit of specific economies of scale.

EU Member States

Czech Republic

In the Czech Republic about 80% of the newspapers and magazines were owned by German and Swiss corporations in 2007, as the two main press groups Vltava Labe Media and Mafra were (completely or partly) controlled by the German group Rheinisch-Bergische Druckerei- und Verlagsgesellschaft (Mediengruppe Rheinische Post), but were both later purchased by Czech-owned conglomerates Penta Investments and Agrofert in 2015 and 2013 respectively. Several major media previously owned by Swiss company Ringier became Czech-owned through their acquisition by the Czech News Center in 2013.

- Vltava Labe Media, a subsidiary of Penta Investments, that owns the tabloids ŠÍP and ŠÍP EXTRA, 73 regional dailies Deník and other 26 weeklies and that is major shareholder of publishing houses Astrosat and Melinor and 100% owner of Metropol and also partly controls the distribution of all the prints through PNS, a.s. which was previously part of the German Verlagsgruppe Passau (that controls also the German Neue Presse Verlags, the Polish Polskapresse and the Slovak Petit Press).

- Mafra, a subsidiary of Agrofert (that owns the centre-right dailies Dnes, Lidové noviny, the local edition of the freesheet Metro, the periodical 14dní, several monthly magazines, the TV music channel Óčko, the radio stations Expresradio and Rádio Classic FM, several web portals and partly controls, together with Vltava-Labe-Press, the distribution company PNS, a.s.) was previously owned by the German Rheinisch-Bergische Drückerei- und Verlagsgesellschaft, prior to its acquisition by Agrofert.

- Czech News Center controls 16 Czech daily tabloids and weeklies (such as 24 hodin, Abc, Aha!, Blesk, Blesk TV Magazin, Blesk pro ženy, Blesk Hobby, Blesk Zdravi, Nedělní Blesk, Nedělní Sport, Reflex, Sport, Sport Magazin) as well as 7 web portals, reaching approximately 3.2 million readers.

Czech governments have defended foreign newspaper ownership as a manifestation of the principle of the free movement of capital.

The weekly Respekt is published by R-Presse, the majority of whose shares are owned by former Czech Minister of Foreign Affairs Karel Schwarzenberg. The national television market is dominated by four terrestrial stations, two public (Czech TV1 and Czech TV2) and two private (NOVA TV and Prima TV), which draw 95% of audience share. Concerning the diversity of output, this is limited by a series of factors: the average low level of professional education among Czech journalists is compensated by "informal professionalization", leading to a degree of conformity in approaches; political parties hold strong ties in Czech media, especially print, where more than 50% of Czech journalists identify with the Right, while only 16% express sympathy for the Left; and the process of commercialization and "tabloidization" has increased, lowering differentiation of content in Czech print media.

Germany

Axel Springer AG is one of the largest newspaper publishing companies in Europe, claiming to have over 150 newspapers and magazines in over 30 countries in Europe. In the 1960s and 1970s the company's media followed an aggressive conservative policy (see Springerpresse). It publishes Germany's only nationwide tabloid, Bild, and one of Germany's most important broadsheets, Die Welt. Axel Springer also owns a number of regional newspapers, especially in Saxony and in the Hamburg Metropolitan Region, giving the company a de facto monopoly in the latter case. An attempt to buy one of Germany's two major private TV Groups, ProSiebenSat.1, in 2006, was withdrawn due to large concerns by regulation authorities as well as by parts of the public. The company is also active in Hungary, where it is the biggest publisher of regional newspapers, and in Poland, where it owns the best-selling tabloid Fakt, one of the nation's most important broadsheets, Dziennik, and is one of the biggest shareholder in the second-ranked private TV company, Polsat.

Bertelsmann is one of the world's largest media companies. It owns RTL Group, which is one of the two major private TV companies in both Germany and the Netherlands and also owning assets in Belgium, France, UK, Spain, Czech and Hungary. Bertelsmann also owns Gruner + Jahr, Germany's biggest popular magazine publisher, including popular news magazine Stern and a 26% share in investigative news magazine Der Spiegel. Bertelsmann also owns Random House, a book publisher, ranked first in the English-speaking world and second in Germany.

Ireland

In Ireland, the company Independent News & Media owns many national newspapers: the Evening Herald, Irish Independent, Sunday Independent, Sunday World and Irish Daily Star. It also owns 29.9% of the Sunday Tribune. Broadcast media is divided between state owned RTÉ, which operates several radio stations and television channels and started digital radio and television services in the early 2010s, TG4, an Irish language broadcaster, and TV3, a commercial television operator. Denis O'Brien an Irish billionaire with a fortune partly accumulated through the Esat Digifone licence controversy, formed Communicorp Group Ltd in 1989, with the company currently owning 42 radio stations in 8 European countries, including Ireland's Newstalk, Today FM, Dublin's 98FM, SPIN 1038 and SPIN South West. In January 2006, O'Brien took a stake in Tony O'Reilly's Independent News & Media (IN&M). As of May 2012, he holds a 29.9% stake in the company, making him the largest shareholder; the O'Reilly family's stake is around 13%.

Italy

Silvio Berlusconi, the former Prime Minister of Italy, is the major shareholder of – by far – Italy's biggest (and de facto only) private free TV company, Mediaset; Italy's biggest publisher, Mondadori; and Italy's biggest advertising company, Publitalia. One of Italy's nationwide dailies, Il Giornale, is owned by his brother, Paolo Berlusconi, and another, Il Foglio, by his former wife, Veronica Lario. Berlusconi has often been criticized for using the media assets he owns to advance his political career.

United Kingdom

In Britain and Ireland, Rupert Murdoch owns best-selling tabloid The Sun as well as the broadsheet The Times and Sunday Times, in addition having also owned 39% of satellite broadcasting network BSkyB. In March 2011, the United Kingdom provisionally approved Murdoch to buy the remaining 61% of BSkyB; however, subsequent events (News of the World hacking scandal and its closure in July 2011) leading to the Leveson Inquiry have halted this takeover. In 2019, despite the British government granting formal permission for a new take over of Sky (conditional on the divestiture of Sky News), Fox were outbid by American conglomerate Comcast.

Reach own five major national titles, the Daily Mirror, Sunday Mirror and The Sunday People, and the Scottish Sunday Mail and Daily Record as well as over 100 regional newspapers. They claim to have a monthly digital reach of 73 million people.

Daily Mail and General Trust (DMGT) own the Daily Mail and The Mail on Sunday, Ireland on Sunday, and free London daily Metro, and control a large proportion of regional media, including through subsidiary Northcliffe Media, in addition to large shares in ITN and GCap Media.

The Guardian is owned by Guardian Media Group.

Richard Desmond owns OK! magazine, the Daily Express, and the Daily Star. He used to own Channel 5; on 1 May 2014 the channel was acquired by Viacom for £450 million (US$759 million).

The Evening Standard and former print publication The Independent are both partly owned by British-Russian media boss Evgeny Lebedev.

BBC News produces news for its television channels and radio stations.

Independent Television News produces news for ITV, Channel 4 and Channel 5.

Independent Radio News, which has a contract with Sky News, produces news for the most popular commercial radio stations.

India

In India a few political parties also own media organizations, for example the proprietors of Kalaignar TV are close aides of Tamil Nadu's former Chief Minister M. Karunanidhi. So is also the case with Sun TV. SRM university owner Pachamuthu, a member of Parliament, has stakes in Pudhiyathalaimurai News Channel. AMMK General Secretary TTV Dinakaran, MLA's close aides run Jaya TV. Sakshi TV a Telugu channel in Andhra Pradesh is owned by ex-chief minister's son and family.

Israel

In Israel, Arnon Mozes owns the most widespread Hebrew newspaper, Yediot Aharonot, the most widespread Russian newspaper Vesty, the most popular Hebrew news website Ynet, and 17% of the cable TV firm HOT. Moreover, Mozes owns the Reshet TV firm, which is one of the two operators of the most popular channel in Israel, Channel 2.

Mexico

In Mexico there are only two national broadcast television service companies, Televisa and Azteca. These two broadcasters together administer 434 of the 461 total commercial television stations in the country (94.14%).

Though concern about the existence of a duopoly had been around for some time, a press uproar sparked in 2006, when a controversial reform to the Federal Radio and Television Law, seriously hampered the entry of new competitors, like Cadena Tres.

Televisa also owns subscription TV enterprises Cablevision (Mexico) and SKY, a publishing company Editorial Televisa, and the Televisa Radio broadcast radio network, creating a de facto media monopoly in many regions of the country.

United States

Recent media mergers in the United States

An infographic created by Jason at Frugal Dad states that in 1983, 90% of US media was controlled by 50 companies, and that in 2011, 90% was controlled by just 6 companies. One of the companies listed, News Corporation, was split into two separate companies on June 28, 2013, with publishing assets and Australian media assets going to News Corp and broadcasting and media assets going to 21st Century Fox.

Film industry

In the United States, movie production has been dominated by major studios since the early 20th century; before that, there was a period in which Edison's Trust monopolized the industry. The music and television industries recently witnessed cases of media consolidation, with Sony Music Entertainment's parent company merging their music division with Bertelsmann AG's BMG to form Sony BMG and Tribune's The WB and CBS Corp.'s UPN merging to form The CW. In the case of Sony BMG, there existed a "Big Five" (now "Big Four") of major record companies, while The CW's creation was an attempt to consolidate ratings and stand up to the "Big Four" of American network (terrestrial) television (this despite the fact that the CW was, in fact, partially owned by one of the Big Four in CBS). In television, the vast majority of broadcast and basic cable networks, over a hundred in all, are controlled by seven corporations: Fox Corporation, The Walt Disney Company (which includes the ABC, ESPN, FX and Disney brands), National Amusements (which owns Paramount Global), Comcast (which owns NBCUniversal), Warner Bros. Discovery, E. W. Scripps Company, Cablevision (now known as Altice USA), or some combination thereof.

There may also be some large-scale owners in an industry that are not the causes of monopoly or oligopoly. iHeartMedia (formerly Clear Channel Communications), especially since the Telecommunications Act of 1996, acquired many radio stations across the United States, and came to own more than 1,200 stations. However, the radio broadcasting industry in the United States and elsewhere can be regarded as oligopolistic regardless of the existence of such a player. Because radio stations are local in reach, each licensing a specific part of spectrum from the FCC in a specific local area, any local market is served by a limited number of stations. In most countries, this system of licensing makes many markets local oligopolies. The similar market structure exists for television broadcasting, cable systems and newspaper industries, all of which are characterized by the existence of large-scale owners. Concentration of ownership is often found in these industries.

Effect of ownership on coverage

In a 2020 article, Herzog and Scerbinina argued that CNN's coverage in 2017 of a potential merger between its parent company Time Warner and AT&T was "self-centered, self-promoting, and self-legitimizing."

Venezuela

About 70% of Venezuelan TV and radio stations are privately owned, while only about 5% or less of these stations are currently state-owned. The remaining stations are mostly community owned. VTV was the only state TV channel in Venezuela only about a decade ago. For the last decade, through the present day, the Venezuelan government operates and owns five more stations.

Commercial outlets completely rule over the radio sector. However, the Venezuelan government funds a good number of radio shows and TV stations. The primary newspapers of Venezuela are private companies that are frequently condemning of their government. These newspapers being produced in Venezuela do not have a large following.