A dictatorship is a form of government characterized by an unelected leader or group of leaders that hold government power with few to no limitations. The leader of a dictatorship is called a dictator. Politics in a dictatorship take place between the dictator, the inner circle, and the opposition, which may be peaceful or violent. Dictatorships can be formed by a military coup that overthrows the previous government through force or by a self-coup in which elected leaders make their rule permanent. Dictatorships can be classified as military dictatorships, one-party dictatorships, personalist dictatorships, or absolute monarchies.

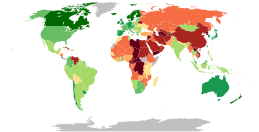

The term dictatorship originates from its use in Roman Republic. Early military dictatorships developed in the post-classical era, particularly in Shogun-era Japan. Modern dictatorships developed in the 19th century as caudillos seized power in Latin America. Fascist states and Communist states emerged in Europe the 1920s and 1930s. Fascism was eradicated in the aftermath of World War II, while Communism spread to other continents. Personalist dictatorships in Africa and military dictatorships in Latin America became prominent in the 1960s and 1970s. Many dictatorships fell during the end of the Cold War and the third wave of democratisation. Many dictatorships still exist, particularly in Africa and Asia.

Dictatorships often hold elections to establish legitimacy or to provide incentives for members of the ruling party, but these elections are not competitive for the opposition. Stability in a dictatorship is maintained through coercion, which involves the restriction of information, tracking of political opposition, and acts of violence. Strong opposition groups can result in the collapse of a dictatorship through a coup or a revolution.

Etymology

The word dictator comes from the Latin language word dictātor, agent noun from dictare (dictāt-, past participial stem of dictāre dictate v. + -or -or suffix). In Latin use, a dictator was a judge in the Roman Republic temporarily invested with absolute power. Typically, in a dictatorial regime, the leader of the country is identified with the title of dictator; although, their formal title may more closely resemble something similar to leader.

Structure

The leader of a dictatorship is called a dictator. The power structures of dictatorships vary, and different definitions of dictatorship consider different elements of this structure. Political scientists such as Juan José Linz and Samuel P. Huntington identify key attributes that define the power structure of a dictatorship, including a single leader or a small group of leaders, the exercise of power with few limitations, limited political pluralism, and limited mass mobilization. Dictatorship may also be defined as a lack of democracy.

The dictator exercises broad power over the government and society, but other individuals are necessary to carry out the dictator's rule. These individuals form an inner circle, making up a class of elites that hold a degree of power within the dictatorship and receive benefits in exchange for their support. They may be military officers, party members, or friends and family of the dictator. Elites are also the primary political threats of a dictator, as they can leverage their power to influence or overthrow the dictatorship. The inner circle's support is necessary for a dictator's orders to be carried out, causing elites to serve as a check on the dictator's power. To enact policy, a dictator must either appease the regime's elites or attempt to replace them. Elites must also compete to wield more power than one another, but the amount of power held by elites also depends on their unity. Factions or divisions among the elites will mitigate their ability to bargain with the dictator, resulting in the dictator having more unrestrained power. A unified inner circle has the capacity to overthrow a dictator, and the dictator must make greater concessions to the inner circle to stay in power. This is particularly true when the inner circle is made up of military officers that have the resources to carry out a military coup.

The opposition to a dictatorship represents all of the factions that are not part of the dictatorship and anyone that does not support the regime. Organized opposition is a threat to the stability of a dictatorship, as it seeks to undermine public support for the dictator and calls for regime change. A dictator may address the opposition by repressing it through force, modifying laws to restrict its power, or appeasing it with limited benefits. The opposition can be an external group, or it can also include current and former members of the dictator's inner circle.

Totalitarianism is a variation of dictatorship characterized by the presence of a single political party and more specifically, by a powerful leader who imposes personal and political prominence. Power is enforced through a steadfast collaboration between the government and a highly developed ideology. A totalitarian government has "total control of mass communications and social and economic organizations". Political philosopher Hannah Arendt describes totalitarianism as a new and extreme form of dictatorship composed of "atomized, isolated individuals" in which ideology plays a leading role in defining how the entire society should be organized. According to Linz, the distinction between an authoritarian regime and a totalitarian one is that an authoritarian regime seeks to suffocate politics and political mobilization while totalitarianism seeks to control and utilize them.

Formation

A dictatorship is formed when a specific group seizes power. The composition of this group affects how power is seized and how the eventual dictatorship will rule. The seizure group may be military or political, it may be organized or disorganized, and it may disproportionately represent a certain demographic. After power is seized, the group must determine what positions its members will hold in the new government and how this government will operate, sometimes resulting in disagreements that split the group. Members of the group will typically make up the elites in a dictator's inner circle at the beginning of a new dictatorship, though the dictator may remove them as a means to gain additional power. Unless they have undertaken a self-coup, seizure groups typically have little governmental experience and do not have a detailed policy plan before taking power. After a dictator seizes power, a political party may be formed to create a mechanism to reward supporters and to concentrate power in the hands of allies instead of armed supporters.

Most dictatorships are formed through military means or through a political party. Nearly half of dictatorships start as a military coup, though others have been started by foreign intervention, elected officials ending competitive elections, insurgent takeovers, popular uprisings by citizens, or a rule-change by autocratic elites to take power within their government. Between 1946 and 2010, 42% of dictatorships began by overthrowing a different dictatorship, and 26% began by declaring independence from a foreign government.

Several theories exist as to why dictatorships form. Mancur Olson suggests that dictatorships are an alternative to "roving bandits"; rather than moving from place to place and extracting wealth, dictators can monopolize banditry in one place while providing an illusion of security to increase productivity. Peter Alter suggests a value system perspective based on cultural & political nation, national consciousness, and nation-building.

Types

Political scientist Barbara Geddes describes three types of dictatorship. Military dictatorships are controlled by military officers, single-party dictatorships are controlled by the members of a political party, and personalist dictatorships are controlled by a single individual. Monarchies are also considered dictatorships in some circumstances if they hold significant political power. Hybrid dictatorships are regimes that have a combination of these classifications. Dictatorships can also be defined by the degree of authoritarianism, the use of loyalty or repression, how they interact with the organization that brought them to power.

Military dictatorships

Military dictatorships are regimes in which one or more military officers holds power, determines who will lead the country, and exercises influence over policy. They are most common in developing nations in Africa, Asia, and Latin America. They are often unstable, and the average duration of a military dictatorship is only five years, but they are often followed by additional military coups and military dictatorships. While common in the 20th century, the prominence of military dictatorships declined in the 1970s and 1980s.

Military dictatorships are typically formed by a military coup in which one or more senior officers uses the military to overthrow the government. In democracies, the threat of a military coup is associated with the period immediately after a democracy's creation but prior to large-scale military reforms. In oligarchies, the threat of a military coup comes from the strength of the military weighed against the concessions made to the military. Other factors associated with military coups include extensive natural resources, limited use of the military internationally, and use of the military as an oppressive force domestically. Military coups do not necessarily result in military dictatorships, as power may then be passed to an individual or the military may allow democratic elections to take place. Military dictatorships in the past have been significantly more common in Latin America.

Military dictatorships often have traits in common due to the shared background of military dictators. These dictators may view themselves as impartial in their oversight of a country due to their nonpartisan status, and they may view themselves as "guardians of the state". The predominance of violent force in military training manifests in an acceptance of violence as a political tool and the ability to organize violence on a large scale. Military dictators may also be less trusting or diplomatic and underestimate the use of bargaining and compromise in politics.

One-party dictatorships

One-party dictatorships are governments in which a single political party dominates politics. Single-party dictatorships are one-party states in which only the party in power is legalized and all opposition parties are banned. Dominant-party dictatorships or electoral authoritarian dictatorships are one-party states in which opposition parties are nominally legal but cannot meaningfully influence government. Single-party dictatorships were more common during the Cold War, but dominant-party dictatorships replaced them after the fall of the Soviet Union. One-party dictatorships are distinct from political parties that were created to serve a dictator; the ruling party in a one-party dictatorship permeates every level of society. One-party dictatorships became prominent in Asia and Eastern Europe during the Cold War as Communist governments were installed in several countries.

One-party dictatorships are more stable than other forms of authoritarian rule, as they are less susceptible to insurgency and see higher economic growth. Ruling parties allow a dictatorship to more broadly influence the populace and facilitate political agreement between party elites. Between 1950 and 2016, one-party dictatorships made up 57% of authoritarian regimes in the world. Due to the structure of their leadership, one-party dictatorships are significantly less likely to face civil conflict, insurgency, or terrorism than other forms of dictatorship. The use of ruling parties also provides more legitimacy to its leadership and elites than other forms of dictatorship.

A ruling party in a one-party dictatorship may rule under any ideology or it may have no guiding ideology. One-party states ruled by Marxist political parties are sometimes distinguished from other types of one-party dictatorship, but they are distinct in ideology rather than function. When a one-party dictatorship develops gradually through legal means, in can result in conflict between the party organization and the state apparatus and civil service as the party rules in parallel and increasingly appoints its own members to positions of power. Parties that take power through violence are often able to implement larger changes in a shorter period of time.

Personalist dictatorships

Personalist dictatorships are regimes in which all power lies in the hands of a single individual. They differ from other forms of dictatorships in their access to key political positions, other fruits of office, and depend much more on the discretion of the dictator. Personalist dictators may be members of the military or leaders of a political party, but neither the military nor the party exercises power independently from the dictator. In personalist dictatorships, the elite corps are usually made up of close friends or family members of the dictator, who typically handpicks these individuals to serve their posts. These dictatorships often emerge either from loosely organized seizures of power, giving the leader opportunity to consolidate power, or from democratically-elected leaders in countries with weak institutions, giving the leader opportunity to change the constitution. Personalist dictatorships are more common in Sub-Saharan Africa due to less established institutions in the region.

Personalist dictators typically favor loyalty over competence in their governments and have a general distrust of intelligentsia. Elites in personalist dictatorships often do not have a professional political career and are unqualified for positions they are given. A personalist dictator will manage these appointees by segmenting the government so that they cannot collaborate. The result is that such regimes have no internal checks and balances, and are thus unrestrained when exerting repression on their people, making radical shifts in foreign policy, or starting wars with other countries. Due to the lack of accountability and the smaller group of elites, personalist dictatorships are more prone to corruption than other forms of dictatorship. According to a 2019 study, personalist dictatorships are more repressive than other forms of dictatorship. Personalist dictatorships often collapse with the death of the dictator. They are more likely to end in violence and less likely to democratize than other forms of dictatorship.

The shift in the power relation between the dictator and its inner circle has severe consequences for the behavior of such regimes as a whole. Many scholars have identified ways in which personalist regimes diverge from other regimes when it comes to their longevity, methods of breakdown, levels of corruption, and proneness to conflicts. Personalist dictatorships on average last twice as long as military dictatorships but not as long as single-party dictatorships. Personalist dictatorships also experience growth differently, as they often lack the institutions or qualified leadership to sustain an economy. Without any checks and balances to their rule, such dictators are domestically unopposed when it comes to unleashing repression, or even starting wars.

Absolute monarchies

An absolute monarchy is a monarchy in which the monarch rules without legal limitations. This makes it distinct from constitutional monarchy and ceremonial monarchy. In an absolute monarchy, power is limited to the royal family, and legitimacy is established by historical factors. In the modern era, absolute monarchies are most common in the Middle East. Montesquieu made a distinction between despots that ruled unrestrained and monarchs that ruled within the laws of a kingdom. Political parties are relatively rare in monarchic dictatorships compared to military or civilian dictatorships. Monarchies may be dynastic, in which the royal family serves as a ruling institution similar to a political party in a one-party state, or they may be non-dynastic, in which the monarch rules independently of the royal family as a personalist dictator. Monarchies allow for strict rules of succession that produce a peaceful transfer of power on the monarch's death, but this can also result in succession disputes if multiple members of the royal family claim a right to succeed.

History

Dictators in the Roman Empire

During the Republican phase of Ancient Rome, a Roman dictator was the special magistrate who held well defined powers, normally for six months at a time, usually in combination with a consulship. These powers were granted during times of crisis in which a single leader was needed to command and restore stability. At least 85 such dictators were chosen over the course of the Roman Republic, the last of which was chosen to wage the Second Punic War. The dictatorship was revived 120 years later through a populist movement led by Sulla, and 33 years after that by Julius Caesar, under whose dictatorship the Roman Republic became the Roman Empire.

Post-classical and early modern dictatorships

Japan and Korea saw several military dictatorships during the post-classical era. During the early stages of the Goguryeo–Tang War in 642, Yeon Gaesomun organized a coup in the Goguryeo Kingdom and established himself as a military dictator. A coup took place in the Goryeo Kingdom in 1170, establishing the Goryeo military regime for the next century. Shogun was the title of the military dictators of Japan beginning with the Kamakura shogunate in 1185 and continuing through other shogunates for over six hundred years. While Shoguns nominally operated under the control of the Emperor of Japan, they served as de facto rulers of Japan and the Japanese military.

The Commonwealth of England under Oliver Cromwell, formed in 1649 after the Second English Civil War, has been described as a military dictatorship by its contemporary opponents and by some modern academics. Maximilien Robespierre has been similarly described as a military dictator while he controlled the National Convention in France and carried out the Reign of Terror in 1793 and 1794.

19th century dictatorships

Dictatorship developed as a major form of government in the 19th century, though in Europe it was often thought of in terms of Bonapartism and Caesarism. The concept of dictatorship was not universally seen pejoratively at the time, with both a tyrannical concept and a quasi-constitutional concept of dictatorship understood to exist. The Spanish American wars of independence took place in the early-19th century, creating many new Latin American governments. Many of these governments fell under the control of caudillos, or personalist strongmen dictators. Most caudillos came from a military background, and their rule was typically associated with pageantry and glamor. Caudillos were often nominally constrained by a constitution, but the caudillo had the power to draft a new constitution as he wished. Many are noted for their cruelty, while others are honored as national heroes.

Many Latin American countries experienced dictatorships by caudillos shortly after their formation in the early-19th century. Juan Manuel de Rosas was a major figure in the formation of Argentina, ruling as dictator from 1829 to 1852. In Guatemala, Rafael Carrera ruled as dictator from 1839 to 1865. In Venezuela, José Antonio Páez ruled in the decades following the country's founding. José Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia ruled Paraguay from its founding until 1840. President Antonio López de Santa Anna of Mexico established himself as a military dictator, and he gave himself the title of His Serene Highness in 1853. He was overthrown and exiled in 1855. President Porfirio Díaz of Mexico took power in 1876 and served as the military dictator until the Mexican Revolution in a period known as the Porfiriato.

Dictatorships of the World Wars

European dictatorships of the World Wars

Dictatorship expanded in early-20th century Europe through a combination of far-left and far-right takeovers. The aftermath of World War I resulted in a major shift in European government, establishing new governments, facilitating internal change in other governments, and redrawing the boundaries between countries. These changes provided opportunities for extremist far-left and far-right political movements to take power.

Vladimir Lenin established Soviet Russia in 1917 as a dictatorship of the proletariat. The Bolshevik government during the Russian Civil War had democratic elements, but following poor electoral performance, Lenin dissolved the Constituent Assembly. The Soviet Union was formed as a dictatorship in 1922 under the control of Lenin and the other Bolsheviks, whose power was enforced through secret police organizations such as the Cheka. Following Lenin's death in 1924, the party chose Joseph Stalin to be its next leader, and Stalin gained total control by 1929. In the following decades, Stalin carried out a totalitarian rule in which all threats to his power were eliminated through purges, eliminating democracy even within the one party system. A Soviet government was briefly established in Hungary in 1919, but it fell the same year.

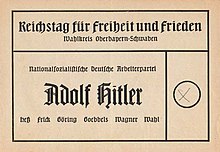

Benito Mussolini was the first fascist dictator. He carried out the March on Rome in 1922, forcing King Victor Emmanuel III to appoint him as Prime Minister of Italy. In 1925, he began implementing his system of fascism, based on totalitarianism, fealty to the state, expansionism, corporatism, and anti-communism, though its application varied and was often inconsistent. Adolf Hitler was appointed chancellor of the Weimar Republic in 1933, his rise to power coinciding with weakening democracy in the country. Over the following six months, Hitler and the Nazi Party obtained absolute power through a combination of electoral victory, violence, and emergency powers, assuming the office of president in addition to chancellor and taking the title of Führer. Austria briefly underwent a period of dictatorship under Engelbert Dollfuss and Kurt Schuschnigg before being annexed by Germany.

Miguel Primo de Rivera was appointed Prime Minister of Spain in 1923 following a military coup, and he ruled as a dictator. By 1930, Primo de Rivera had alienated every major faction of Spanish politics and was convinced to step down. His government was replaced by the Second Spanish Republic. In 1926, Manuel Gomes da Costa led a military coup and established the Ditadura Nacional in Portugal. His successor, Óscar Carmona, chose to give control of finances to economics professor António de Oliveira Salazar. Salazar became Prime Minister of Portugal in 1932 and established the Estado Novo. Francisco Franco took power in Spain after leading the Nationalist faction to victory in the Spanish Civil War and became a dictator in 1939.

The Baltic states all became dictatorships between the World Wars. Antanas Smetona took power in Lithuania in 1926, Konstantin Päts took power in Estonia in 1934, and Kārlis Ulmanis took power in Latvia in 1934. The dictatorships in the Baltic states were considered to be milder than those in other European countries, with private enterprise and the press being relatively free. These dictatorships ended after they were occupied in World War II.

Several right-wing dictatorships also emerged in the Balkans during the interwar period. Bulgaria underwent a period of several dictatorships following a military coup in 1923. Ahmed Zogu overthrew the government in Albania in 1924, and he proclaimed himself King Zog I in 1928. He was dictator until Albania was occupied in World War II. King George II of Greece appointed Ioannis Metaxas as Prime Minister of Greece in 1936, and Metaxas ruled as a dictator until his death in 1941. In 1940, King Michael I of Romania granted Ion Antonescu dictatorial powers, and Antonescu declared himself the Conducător of Romania.

During World War II, Germany and Italy occupied several European countries and established fascist client states. These include Albania, Belgium, the Czech lands, Denmark, France, Greece, Hungary, the Netherlands, Poland, Norway, the Slovak Republic, Yugoslavia and The Soviet Union. Poland was occupied by both Germany and the Soviet Union. Allied victory in Europe and the fall of Nazi Germany resulted in the liberation of Nazi-occupied territories and the dissolving of fascist governments.

Latin American dictatorships of the World Wars

Augusto B. Leguía ruled as a dictator in Peru from 1919 to 1930. Juan Vicente Gómez ruled Venezuela as a dictator from 1908 until his death in 1935. Rafael Trujillo took power as a "nearly totalitarian" dictator of the Dominican Republic in the 1930s and ruled for 30 years. The 1930 Argentine coup d'état was the first in a series of coups and military dictatorships that would affect the country for decades. Jorge Ubico took power in Guatemala in 1931 and ruled until he was deposed by a pro-democracy uprising in 1944. In 1931, a coup was organized against the government of Arturo Araujo, causing the period of military dictatorship in El Salvador, starting with the Civic Directory. The government committed several crimes against humanity, such as those of La Matanza. The dictatorship ended with the 1979 Salvadoran coup d'état and the start of the Salvadoran Civil War. President Tiburcio Carías Andino carried out a self-coup in Honduras after the election of 1932 and served as a dictator until 1949. A self-coup in Uruguay established Gabriel Terra as dictator in 1933. Getúlio Vargas led a coup in 1937 that established him as a dictator in Brazil under an Estado Novo system. In Paraguay, Higinio Morínigo established himself as a military dictator in 1940 and ruled until 1948.

Dictatorships of the Cold War

African dictatorships of the Cold War

Many dictatorships formed in Africa, with most forming after countries gained independence during decolonisation. Mobutu Sese Seko ruled the Democratic Republic of the Congo as a dictator for decades, renaming it Zaire. Teodoro Obiang Nguema Mbasogo has ruled Equatorial Guinea as a dictator since he led a military coup in 1979. In 1973, King Sobhuza II of Swaziland suspended the constitution and ruled as an absolute monarch. Samuel Doe established a military dictatorship in Liberia in the 1980s. Libya was ruled by Muammar Gaddafi for several decades following a military coup. Moussa Traoré ruled as a dictator in Mali. Habib Bourguiba ruled as a dictator in Tunisia until he was deposed by a coup led by Zine El Abidine Ben Ali in 1987, who in turn ruled as a dictator until the Tunisian Revolution in 2011. Robert Mugabe ruled as a dictator in Zimbabwe.

Early socialist dictatorships in Africa mainly developed as personalist dictatorships, in which a single socialist would take power instead of a ruling party. Later in the Cold War, the Soviet Union increased its influence in Africa as Marxist-Leninist dictatorships developed in several African countries. One-party Marxist states in Africa included Angola under the MPLA, Benin under Mathieu Kérékou, Cape Verde under the PAICV, the Congo under the Congolese Party of Labour, Ethiopia under the Workers' Party of Ethiopia, Madagascar under AREMA, Mozambique under FRELIMO, and Somalia under Siad Barre.

Many African countries underwent several military coups that installed a series of military dictatorships throughout the Cold War. These include Benin, Burkina Faso, Burundi, the Central African Republic, Comoros, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ethiopia, Ghana, Mauritania, Niger, Nigeria, Sierra Leone, Sudan, and Uganda, each undergoing at least three successful military coups between 1959 and 2001.

Some leaders of African countries abolished opposition parties, establishing one-party dictatorships. These include the National Liberation Front in Algeria, the Chadian Progressive Party under François Tombalbaye in Chad, the Gabonese Democratic Party under Omar Bongo in Gabon, the Democratic Party under Ahmed Sékou Touré in Guinea, the Malawi Congress Party under Hastings Banda in Malawi, the MNSD under Ali Saibou in Niger, MRND under Juvénal Habyarimana in Rwanda, the Socialist Party under Léopold Sédar Senghor in Senegal, Julius Nyerere in Tanzania, the RPT under Gnassingbé Eyadéma in Togo, and the United National Independence Party under Kenneth Kaunda in Zambia. The KANU in Kenya ruled under a de facto one-party state.

Asian dictatorships of the Cold War

Mao Zedong established the People's Republic of China as a one-party Communist state at the end of the Chinese Civil War in 1949, removing the Nationalist Chinese government from power. Mao implemented his governing ideology of Maoism. The country maintained a strained relationship with the Soviet Union, and relations deteriorated as the Soviet Union underwent de-Stalinization in the late-1950s. In the 1960s, amid fear that he would lose control of the Communist Party, Mao initiated the Cultural Revolution, which involved the destruction of any elements of capitalism in China while also establishing relations with Japan and the United States. Deng Xiaoping took power as the de facto leader of China after Mao's death and implemented reforms to restore stability following the Cultural Revolution and reestablish free market economics. Chiang Kai-shek continued to rule as dictator of the National government's rump state in Taiwan until his death in 1975.

North Korea and South Korea both emerged from World War II as dictatorships. North Korea was established under Soviet influence, and Kim Il-sung led the country as a one-party Marxist state. South Korea was under the dictatorship of Syngman Rhee in the 1950s, but his rule ended following the April Revolution. The country became a military dictatorship under Chun Doo-hwan in the 1980s, but the June Democratic Struggle in 1987 led to democratization. In Southern Asia, Ayub Khan established himself as a military dictator of Pakistan during the 1958 coup, and Muhammad Zia-ul-Haq established himself as a military dictator in the 1977 coup. Hussain Muhammad Ershad took power in Bangladesh in a 1982 military coup and ruled until 1991. Nepal was an absolute monarchy until the 1990 Nepalese revolution created a constitutional monarchy.

Southeast Asia was influenced by China during the Cold War, and three Communist dictatorships were formed in the region: North Vietnam, Laos, and Kampuchea. North Vietnam conquered South Vietnam at the end of the Vietnam War, and the two merged into a single Communist country. Anti-Communist dictators also ruled in the region. Suharto became dictator in Indonesia, taking power in 1967 until a violent unrest in 1998 forced him to resign. Ngo Dinh Diem ruled South Vietnam as a dictator until the 1963 military coup. Ferdinand Marcos ruled Philippines as a dictator until the People Power Revolution in 1986. A socialist military dictatorship was also created separately from the Communist governments in Burma until it was overthrown in 1988 and replaced by a new military dictatorship.

The Middle East was decolonized during the Cold War, and many nationalist movements gained strength post-independence. A 1953 coup overseen by the American and British governments restored Mohammad Reza Pahlavi as the absolute monarch of Iran, who in turn was overthrown during the Iranian Revolution of 1979 that established Ruhollah Khomeini as Supreme Leader of Iran under an Islamist government. Several Middle Eastern countries were the subject of military coups in the 1950s and 1960s, including Iraq, Syria, North Yemen, and South Yemen. Afghanistan became a one-party dictatorship after the 1973 coup, and it became a Marxist dictatorship after the Saur Revolution in 1978.

European dictatorships of the Cold War

During World War II, the countries of Central and Eastern Europe had been occupied by the Soviet Union. When the war ended, these countries were incorporated into the Soviet sphere of influence, and the Soviet Union exercised control over their governments. Soviet occupation of Bulgaria and Poland allowed for the immediate establishment of a new government. The Soviet occupation of East Germany resulted in the creation of a new one-party state controlled by the Socialist Unity Party of Germany. The Czechoslovak government was replaced by the Ninth-of-May Constitution, which maintained a facade of democracy while the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia held authority. Following the liberation of Hungary, Communists gained influence in the country by infiltrating its government and carrying out a Communist takeover, implementing a new constitution to implement one party rule. The Soviet government pressured King Michael I of Romania to appoint Petru Groza as Prime Minister of Romania, and Groza's government enacted a new constitution to implement Communist rule.

Josip Broz Tito declared a Communist government in Yugoslavia during World War II, and Soviet occupation established this government as the sole authority in the country. Tito's government was initially aligned with the Soviet Union, but relations between the countries were strained by Soviet attempts to influence Yugoslavia. Albania was established as a Communist dictatorship under Enver Hoxha in 1944. It was initially aligned with Yugoslavia, but its alignment shifted throughout the Cold War between Yugoslavia, the Soviet Union, and China. The stability of the Soviet Union weakened in the 1980s. The Soviet economy became unsustainable, and Communist governments lost the support of intellectuals. In 1989, the Soviet Union was dissolved, and Communism was abandoned by the countries of Central and Eastern Europe. Of the new and reformed governments created by the fall of Communism in Europe, only Belarus remained a dictatorship, under the control of Alexander Lukashenko.

Latin American dictatorships of the Cold War

Military dictatorships remained prominent in Latin America during the Cold War, though the number of coups declined starting in the 1980s. Between 1967 and 1991, Haiti and Honduras both underwent three military coups, and Bolivia underwent eight. Argentina, Chile, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay also underwent at least one military coup during the same period.

In the Caribbean, former President of Cuba Fulgencio Batista carried out a 1952 military coup in Cuba after he determined that he was not going to win the upcoming presidential election. Batista ruled until the Cuban Revolution overthrew his government and established a one-party Marxist state led by Fidel Castro. Jean-Claude Duvalier consolidated his power as a dictator in Haiti during his presidency in the 1970s, and upon his death in 1971, he passed his position to his son Jean-Claude Duvalier, who would rule until 1986.

In Central America, Carlos Castillo Armas took power in Guatemala with a 1954 coup with American-trained troops and held power until his assassination in 1957, which in turn resulted in a series of dictatorships during the Guatemalan Civil War. Omar Torrijos took power in Panama with a 1968 military coup until his death in 1981. Several military dictators briefly held power in Panama until Manuel Noriega took power in 1983, but he was deposed by the United States invasion of Panama in 1989. The Somoza family ruled Nicaragua either directly or indirectly until they were overthrown during the Nicaraguan Revolution in 1979.

In South America, a 1948 military coup in Venezuela established the dictatorship of Marcos Pérez Jiménez who ruled until 1958. Gustavo Rojas Pinilla took power in a 1953 coup and ruled until 1957. Alfredo Stroessner carried out a 1954 military coup in Paraguay that established the El Stronato military dictatorship until 1989. A 1964 coup established a military dictatorship in Brazil that lasted until 1985. A 1968 military coup established a military dictatorship in Peru until 1980, and in 1992, Alberto Fujimori carried out a self-coup in Peru. Hugo Banzer was the military dictator of Bolivia from 1971 to 1978, and he would later go on to be the country's democratically elected president two decades later. In 1972, Guillermo Rodríguez established a dictatorial government in Ecuador and called his government the "Nationalist Revolution". It entered OPEC in 1973 and also imposed agrarian reforms. In 1973, Augusto Pinochet carried out a coup and established a military dictatorship in Chile that lasted until 1990.

Operation Condor was a secret intelligence agreement developed by Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet with his secret police and intelligence organizations. It included the governments of military dictatorships in Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Ecuador, Uruguay, Paraguay, and Peru. Under this organization, these governments were able to collaborate with one another in the elimination of political enemies. Operation Condor received tacit and sometimes explicit support from the United States in exchange for support against Communist dictators, and the United States declassified information on Operation Condor after the Cold War.

21st century dictatorships

The nature of dictatorship changed in much of the world at the onset of the 21st century. Between the 1990s and the 2000s, most dictators moved away from being "larger-than-life figures" that controlled the populace through terror and isolated themselves from the global community. This was replaced by a trend of developing a positive public image to maintain support among the populace and moderating rhetoric to integrate with the global community.

Only a small number of one-party states exist in the 21st century. As of 2022, China, Cuba, Laos, North Korea, and Vietnam are Communist one-party states, and Eritrea is a nationalist one-party state. Opposition parties were legalized in Syria and Turkmenistan, but they are still de facto one-party states as of 2022. Other countries with dominant-party systems also exist. Iraq was a one-party state until the 2003 invasion of Iraq. As of 2022, Brunei, Eswatini, Oman, Saudi Arabia, and Vatican City are absolute monarchies, and the United Arab Emirates is a federation of monarchies. Bhutan was an absolute monarchy until the 2008 Bhutanese National Assembly election. Tonga was an absolute monarchy until the 2010 Tongan general election. Belarus under the rule of Alexander Lukashenko has been described as "the last European dictatorship", though the rule of Vladimir Putin in Russia has also been described as a dictatorship.

Measurement

One of the tasks in political science is to measure and classify regimes as either dictatorships or democracies. Freedom House, the Polity data series, and the Democracy-Dictatorship Index are three of the most used data series by political scientists. Generally, two research approaches exist: the minimalist approach, which focuses on whether a country has continued elections that are competitive, and the substantive approach, which expands the concept of democracy to include human rights, freedom of the press, and the rule of law. The Democracy-Dictatorship Index is seen as an example of the minimalist approach, whereas the Polity data series is more substantive.

Economics

Most dictatorships exist in countries with high levels of poverty. Poverty has a destabilizing effect on government, causing democracy to fail and regimes to fall more often. The form of government does not correlate with the amount of economic growth, and dictatorships on average grow at the same rate as democracies, though dictatorships have been found to have larger fluctuations. Dictators are more likely to implement long-term investments into the country's economy if they feel secure in their power. Exceptions to the pattern of poverty in dictatorships include oil-rich Middle Eastern dictatorships and the East Asian Tigers during their periods of dictatorship.

The type of economy in a dictatorship can affect how it functions. Economies based on natural resources allow dictators more power, as they can easily extract rents without strengthening or cooperating with other institutions. More complex economies require additional cooperation between the dictator and other groups. The economic focus of a dictatorship often depends on the strength of the opposition, as a weaker opposition allows a dictator to extract additional wealth from the economy through corruption.

Legitimacy and stability

Several factors determine the stability of a dictatorship. They must maintain some degree of popular support to prevent resistance groups from growing. This may be ensured through incentives, such as distribution of financial resources or promises of security, or it may be through repression, in which failing to support the regime is punished. Stability can be weakened when opposition groups grow and unify or when elites are not loyal to the regime. One-party dictatorships are generally more stable and last longer than military or personalist dictatorships.

A dictatorship may fall because of a military coup, foreign intervention, negotiation, or popular revolution. A military coup is often carried out when a regime is threatening the country's stability or during periods of societal unrest. Foreign intervention takes place when another country seeks to topple a regime by invading the country or supporting the opposition. A dictator may negotiate the end of a regime if it has lost legitimacy or if a violent removal seems likely. Revolution takes place when the opposition group grows large enough that elites in the regime cannot suppress it or choose not to. Negotiated removals are more likely to end in democracy, while removals by force are more likely to result in a new dictatorial regime. A dictator that has concentrated significant power is more likely to be exiled, imprisoned, or killed after ouster, and accordingly they are more likely to refuse negotiation and cling to power.

Dictatorships are typically more aggressive than democracy when in conflict with other nations, as dictators do not have to fear electoral costs of war. Military dictatorships are more prone to conflict due to the inherent military strength associated with such a regime, and personalist dictatorships are more prone to conflict due to the weaker institutions to check the dictator's power. In the 21st century, dictatorships have moved toward greater integration with the global community and increasingly attempt to present themselves as democratic. Dictatorships are often recipients of foreign aid on the condition that they make advances toward democratization. A study found that dictatorships that engage in oil drilling are more likely to remain in power, with 70.63% of the dictators who engage in oil drilling still being in power after 5 years of dictatorship, while only 59.92% of the non-oil producing dictators survive the first 5 years.

Elections

Most dictatorships hold elections to maintain legitimacy and stability, but these elections are typically uncompetitive and the opposition is not permitted to win. Elections allow a dictatorship to exercise some control over the opposition by setting the terms under which the opposition challenges the regime. Elections are also used to control elites within the dictatorship by requiring them to compete with one another and incentivizing them to build support with the populace, allowing the most popular and most competent elites to be promoted in the regime. Elections also support the legitimacy of a dictatorship by presenting the image of a democracy, establishing plausible deniability of its status as a dictatorship for both the populace and foreign governments. Should a dictatorship fail, elections also permit dictators and elites to accept defeat without fearing violent recourse. Dictatorships may influence the results of an election through electoral fraud, intimidation or bribing of candidates and voters, use of state resources such as media control, manipulation of electoral laws, restricting who may run as a candidate, or disenfranchising demographics that may oppose the dictatorship.

Before 1990, most dictatorships held elections in which voters could only choose to support the dictatorship. Since the end of the Cold War, more dictatorships have established "semi-competitive" elections in which opposition parties are allowed to participate but they are not allowed to win. This may be done by preventing the opposition from campaigning, banning more popular opposition parties, preventing opposition members from forming a party, or requiring that candidates be a member of the ruling party. Dictatorships may hold semi-competitive elections to qualify for foreign aid or to incentivize the party to expand its information-gathering capacity, particularly at the local level. Semi-competitive elections also have the effect of incentivizing members of the ruling party to provide better treatment of citizens so they will be chosen as party nominees due to their popularity.

Violence

Violence is used in dictatorships to coerce any opposition to the dictator's rule, often through institutions such as military or police forces. The use of violence by a dictator is often most severe in the first few years of a dictatorship, as the regime has not yet solidified its rule and more detailed information for targeted coercion is not yet available. As the dictatorship becomes more established, it moves away from violence toward other coercive measures, such as restriction of information and tracking of political opposition. Institutions that coerce the opposition through violence may serve different roles or be used to counterbalance one another to prevent one from growing too powerful. Secret police are used to gather information on and carry out targeted acts of violence against specific political opponents, and paramilitary forces defend the regime from coups, and formal militaries defend the dictatorship during foreign invasion and major civil conflicts.

Terrorism is less common in dictatorships. Allowing the opposition to have representation in the regime, such as through a legislature, further reduces the likelihood of terrorist attacks in a dictatorship. Military and one-party dictatorships are more likely to experience terrorism than personalist dictatorships, as these regimes are under more pressure to undergo institutional change in response to terrorism.