In mathematics and physics, a vector space (also called a linear space) is a set whose elements, often called vectors, may be added together and multiplied ("scaled") by numbers called scalars. Scalars are often real numbers, but can be complex numbers or, more generally, elements of any field. The operations of vector addition and scalar multiplication must satisfy certain requirements, called vector axioms. The terms real vector space and complex vector space are often used to specify the nature of the scalars: real coordinate space or complex coordinate space.

Vector spaces generalize Euclidean vectors, which allow modeling of physical quantities, such as forces and velocity, that have not only a magnitude, but also a direction. The concept of vector spaces is fundamental for linear algebra, together with the concept of matrices, which allows computing in vector spaces. This provides a concise and synthetic way for manipulating and studying systems of linear equations.

Vector spaces are characterized by their dimension, which, roughly speaking, specifies the number of independent directions in the space. This means that, for two vector spaces over a given field and with the same dimension, the properties that depend only on the vector-space structure are exactly the same (technically the vector spaces are isomorphic). A vector space is finite-dimensional if its dimension is a natural number. Otherwise, it is infinite-dimensional, and its dimension is an infinite cardinal. Finite-dimensional vector spaces occur naturally in geometry and related areas. Infinite-dimensional vector spaces occur in many areas of mathematics. For example, polynomial rings are countably infinite-dimensional vector spaces, and many function spaces have the cardinality of the continuum as a dimension.

Many vector spaces that are considered in mathematics are also endowed with other structures. This is the case of algebras, which include field extensions, polynomial rings, associative algebras and Lie algebras. This is also the case of topological vector spaces, which include function spaces, inner product spaces, normed spaces, Hilbert spaces and Banach spaces.

Definition and basic properties

In this article, vectors are represented in boldface to distinguish them from scalars.

A vector space over a field F is a non-empty set V together with two binary operations that satisfy the eight axioms listed below. In this context, the elements of V are commonly called vectors, and the elements of F are called scalars.

- The first operation, called vector addition or simply addition assigns to any two vectors v and w in V a third vector in V which is commonly written as v + w, and called the sum of these two vectors.

- The second operation, called scalar multiplication,assigns to any scalar a in F and any vector v in V another vector in V, which is denoted av.

To have a vector space, the eight following axioms must be satisfied for every u, v and w in V, and a and b in F.

| Axiom | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Associativity of vector addition | u + (v + w) = (u + v) + w |

| Commutativity of vector addition | u + v = v + u |

| Identity element of vector addition | There exists an element 0 ∈ V, called the zero vector, such that v + 0 = v for all v ∈ V. |

| Inverse elements of vector addition | For every v ∈ V, there exists an element −v ∈ V, called the additive inverse of v, such that v + (−v) = 0. |

| Compatibility of scalar multiplication with field multiplication | a(bv) = (ab)v |

| Identity element of scalar multiplication | 1v = v, where 1 denotes the multiplicative identity in F. |

| Distributivity of scalar multiplication with respect to vector addition | a(u + v) = au + av |

| Distributivity of scalar multiplication with respect to field addition | (a + b)v = av + bv |

When the scalar field is the real numbers the vector space is called a real vector space. When the scalar field is the complex numbers, the vector space is called a complex vector space. These two cases are the most common ones, but vector spaces with scalars in an arbitrary field F are also commonly considered. Such a vector space is called an F-vector space or a vector space over F.

An equivalent definition of a vector space can be given, which is much more concise but less elementary: the first four axioms (related to vector addition) say that a vector space is an abelian group under addition, and the four remaining axioms (related to the scalar multiplication), say that this operation defines a ring homomorphism from the field F into the endomorphism ring of this group.

Subtraction of two vectors can be defined as

Direct consequences of the axioms include that, for every and one has

- implies or

Even more concisely, a vector space is an -module, where is a field.

Related concepts and properties

- Linear combination

- Given a set G of elements of a F-vector space V, a linear combination of elements of G is an element of V of the form where and The scalars are called the coefficients of the linear combination.

- Linear independence

- The elements of a subset G of a F-vector space V are said to be linearly independent if no element of G can be written as a linear combination of the other elements of G. Equivalently, they are linearly independent if two linear combinations of elements of G define the same element of V if and only if they have the same coefficients. Also equivalently, they are linearly independent if a linear combination results in the zero vector if and only if all its coefficients are zero.

- Linear subspace

- A linear subspace or vector subspace W of a vector space V is a non-empty subset of V that is closed under vector addition and scalar multiplication; that is, the sum of two elements of W and the product of an element of V by a scalar belong to W. This implies that every linear combination of elements of W belongs to W.

A linear subspace is a vector space for the induced addition and scalar

multiplication; this means that the closure property implies that the

axioms of a vector space are satisfied.

The closure property also implies that every intersection of linear subspaces is a linear subspace. - Linear span

- Given a subset G of a vector space V, the linear span or simply the span of G is the smallest linear subspace of V that contains G, in the sense that it is the intersection of all linear subspaces that contain G. The span of G is also the set of all linear combinations of elements of G.

If W is the span of G, one says that G spans or generates W, and that G is a spanning set or a generating set of W. - Basis and dimension

- A subset of a vector space is a basis if its elements are linearly independent and span the vector space. Every vector space has at least one basis, generally many (see Basis (linear algebra) § Proof that every vector space has a basis). Moreover, all bases of a vector space have the same cardinality, which is called the dimension of the vector space (see Dimension theorem for vector spaces). This is a fundamental property of vector spaces, which is detailed in the remainder of the section.

Bases are a fundamental tool for the study of vector spaces, especially when the dimension is finite. In the infinite-dimensional case, the existence of infinite bases, often called Hamel bases, depend on the axiom of choice. It follows that, in general, no base can be explicitly described. For example, the real numbers form an infinite-dimensional vector space over the rational numbers, for which no specific basis is known.

Consider a basis of a vector space V of dimension n over a field F. The definition of a basis implies that every may be written

The one-to-one correspondence between vectors and their coordinate vectors maps vector addition to vector addition and scalar multiplication to scalar multiplication. It is thus a vector space isomorphism, which allows translating reasonings and computations on vectors into reasonings and computations on their coordinates. If, in turn, these coordinates are arranged as matrices, these reasonings and computations on coordinates can be expressed concisely as reasonings and computations on matrices. Moreover, a linear equation relating matrices can be expanded into a system of linear equations, and, conversely, every such system can be compacted into a linear equation on matrices.

In summary, finite-dimensional linear algebra may be expressed in three equivalent languages:

- Vector spaces, which provide concise and coordinate-free statements,

- Matrices, which are convenient for expressing concisely explicit computations,

- Systems of linear equations, which provide more elementary formulations.

History

Vector spaces stem from affine geometry, via the introduction of coordinates in the plane or three-dimensional space. Around 1636, French mathematicians René Descartes and Pierre de Fermat founded analytic geometry by identifying solutions to an equation of two variables with points on a plane curve. To achieve geometric solutions without using coordinates, Bolzano introduced, in 1804, certain operations on points, lines and planes, which are predecessors of vectors. Möbius (1827) introduced the notion of barycentric coordinates. Bellavitis (1833) introduced an equivalence relation on directed line segments that share the same length and direction which he called equipollence. A Euclidean vector is then an equivalence class of that relation.

Vectors were reconsidered with the presentation of complex numbers by Argand and Hamilton and the inception of quaternions by the latter. They are elements in R2 and R4; treating them using linear combinations goes back to Laguerre in 1867, who also defined systems of linear equations.

In 1857, Cayley introduced the matrix notation which allows for a harmonization and simplification of linear maps. Around the same time, Grassmann studied the barycentric calculus initiated by Möbius. He envisaged sets of abstract objects endowed with operations. In his work, the concepts of linear independence and dimension, as well as scalar products are present. Actually Grassmann's 1844 work exceeds the framework of vector spaces, since his considering multiplication, too, led him to what are today called algebras. Italian mathematician Peano was the first to give the modern definition of vector spaces and linear maps in 1888, although he called them "linear systems".

An important development of vector spaces is due to the construction of function spaces by Henri Lebesgue. This was later formalized by Banach and Hilbert, around 1920. At that time, algebra and the new field of functional analysis began to interact, notably with key concepts such as spaces of p-integrable functions and Hilbert spaces. Also at this time, the first studies concerning infinite-dimensional vector spaces were done.

Examples

Arrows in the plane

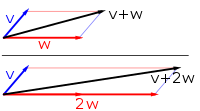

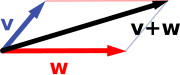

The first example of a vector space consists of arrows in a fixed plane, starting at one fixed point. This is used in physics to describe forces or velocities. Given any two such arrows, v and w, the parallelogram spanned by these two arrows contains one diagonal arrow that starts at the origin, too. This new arrow is called the sum of the two arrows, and is denoted v + w. In the special case of two arrows on the same line, their sum is the arrow on this line whose length is the sum or the difference of the lengths, depending on whether the arrows have the same direction. Another operation that can be done with arrows is scaling: given any positive real number a, the arrow that has the same direction as v, but is dilated or shrunk by multiplying its length by a, is called multiplication of v by a. It is denoted av. When a is negative, av is defined as the arrow pointing in the opposite direction instead.

The following shows a few examples: if a = 2, the resulting vector aw has the same direction as w, but is stretched to the double length of w (right image below). Equivalently, 2w is the sum w + w. Moreover, (−1)v = −v has the opposite direction and the same length as v (blue vector pointing down in the right image).

|

|

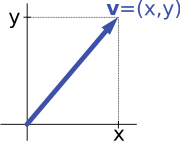

Second example: ordered pairs of numbers

A second key example of a vector space is provided by pairs of real numbers x and y. (The order of the components x and y is significant, so such a pair is also called an ordered pair.) Such a pair is written as (x, y). The sum of two such pairs and multiplication of a pair with a number is defined as follows:

The first example above reduces to this example, if an arrow is represented by a pair of Cartesian coordinates of its endpoint.

Coordinate space

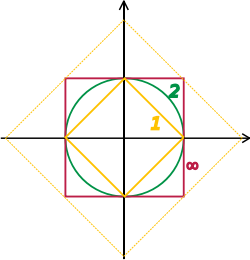

The simplest example of a vector space over a field F is the field F itself (as it is an abelian group for addition, a part of the requirements to be a field), equipped with its addition (It becomes vector addition.) and multiplication (It becomes scalar multiplication.). More generally, all n-tuples (sequences of length n)

Complex numbers and other field extensions

The set of complex numbers C, that is, numbers that can be written in the form x + iy for real numbers x and y where i is the imaginary unit, form a vector space over the reals with the usual addition and multiplication: (x + iy) + (a + ib) = (x + a) + i(y + b) and c ⋅ (x + iy) = (c ⋅ x) + i(c ⋅ y) for real numbers x, y, a, b and c. The various axioms of a vector space follow from the fact that the same rules hold for complex number arithmetic.

In fact, the example of complex numbers is essentially the same as (that is, it is isomorphic to) the vector space of ordered pairs of real numbers mentioned above: if we think of the complex number x + i y as representing the ordered pair (x, y) in the complex plane then we see that the rules for addition and scalar multiplication correspond exactly to those in the earlier example.

More generally, field extensions provide another class of examples of vector spaces, particularly in algebra and algebraic number theory: a field F containing a smaller field E is an E-vector space, by the given multiplication and addition operations of F. For example, the complex numbers are a vector space over R, and the field extension is a vector space over Q.

Function spaces

Functions from any fixed set Ω to a field F also form vector spaces, by performing addition and scalar multiplication pointwise. That is, the sum of two functions f and g is the function given by

Linear equations

Systems of homogeneous linear equations are closely tied to vector spaces. For example, the solutions of

where is the matrix containing the coefficients of the given equations, is the vector denotes the matrix product, and is the zero vector. In a similar vein, the solutions of homogeneous linear differential equations form vector spaces. For example,

yields where and are arbitrary constants, and is the natural exponential function.

Linear maps and matrices

The relation of two vector spaces can be expressed by linear map or linear transformation. They are functions that reflect the vector space structure, that is, they preserve sums and scalar multiplication:

An isomorphism is a linear map f : V → W such that there exists an inverse map g : W → V, which is a map such that the two possible compositions f ∘ g : W → W and g ∘ f : V → V are identity maps. Equivalently, f is both one-to-one (injective) and onto (surjective). If there exists an isomorphism between V and W, the two spaces are said to be isomorphic; they are then essentially identical as vector spaces, since all identities holding in V are, via f, transported to similar ones in W, and vice versa via g.

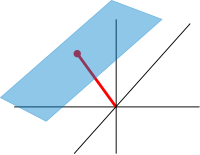

For example, the "arrows in the plane" and "ordered pairs of numbers" vector spaces in the introduction are isomorphic: a planar arrow v departing at the origin of some (fixed) coordinate system can be expressed as an ordered pair by considering the x- and y-component of the arrow, as shown in the image at the right. Conversely, given a pair (x, y), the arrow going by x to the right (or to the left, if x is negative), and y up (down, if y is negative) turns back the arrow v.

Linear maps V → W between two vector spaces form a vector space HomF(V, W), also denoted L(V, W), or 𝓛(V, W). The space of linear maps from V to F is called the dual vector space, denoted V∗. Via the injective natural map V → V∗∗, any vector space can be embedded into its bidual; the map is an isomorphism if and only if the space is finite-dimensional.

Once a basis of V is chosen, linear maps f : V → W are completely determined by specifying the images of the basis vectors, because any element of V is expressed uniquely as a linear combination of them. If dim V = dim W, a 1-to-1 correspondence between fixed bases of V and W gives rise to a linear map that maps any basis element of V to the corresponding basis element of W. It is an isomorphism, by its very definition. Therefore, two vector spaces over a given field are isomorphic if their dimensions agree and vice versa. Another way to express this is that any vector space over a given field is completely classified (up to isomorphism) by its dimension, a single number. In particular, any n-dimensional F-vector space V is isomorphic to Fn. There is, however, no "canonical" or preferred isomorphism; actually an isomorphism φ : Fn → V is equivalent to the choice of a basis of V, by mapping the standard basis of Fn to V, via φ. The freedom of choosing a convenient basis is particularly useful in the infinite-dimensional context; see below.

Matrices

Matrices are a useful notion to encode linear maps. They are written as a rectangular array of scalars as in the image at the right. Any m-by-n matrix gives rise to a linear map from Fn to Fm, by the following

Moreover, after choosing bases of V and W, any linear map f : V → W is uniquely represented by a matrix via this assignment.

The determinant det (A) of a square matrix A is a scalar that tells whether the associated map is an isomorphism or not: to be so it is sufficient and necessary that the determinant is nonzero. The linear transformation of Rn corresponding to a real n-by-n matrix is orientation preserving if and only if its determinant is positive.

Eigenvalues and eigenvectors

Endomorphisms, linear maps f : V → V, are particularly important since in this case vectors v can be compared with their image under f, f(v). Any nonzero vector v satisfying λv = f(v), where λ is a scalar, is called an eigenvector of f with eigenvalue λ. Equivalently, v is an element of the kernel of the difference f − λ · Id (where Id is the identity map V → V). If V is finite-dimensional, this can be rephrased using determinants: f having eigenvalue λ is equivalent to

Basic constructions

In addition to the above concrete examples, there are a number of standard linear algebraic constructions that yield vector spaces related to given ones. In addition to the definitions given below, they are also characterized by universal properties, which determine an object by specifying the linear maps from to any other vector space.

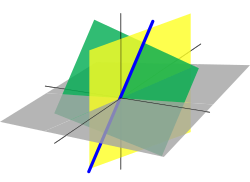

Subspaces and quotient spaces

A nonempty subset of a vector space that is closed under addition and scalar multiplication (and therefore contains the -vector of ) is called a linear subspace of or simply a subspace of when the ambient space is unambiguously a vector space. Subspaces of are vector spaces (over the same field) in their own right. The intersection of all subspaces containing a given set of vectors is called its span, and it is the smallest subspace of containing the set Expressed in terms of elements, the span is the subspace consisting of all the linear combinations of elements of

A linear subspace of dimension 1 is a vector line. A linear subspace of dimension 2 is a vector plane. A linear subspace that contains all elements but one of a basis of the ambient space is a vector hyperplane. In a vector space of finite dimension a vector hyperplane is thus a subspace of dimension

The counterpart to subspaces are quotient vector spaces. Given any subspace the quotient space (" modulo ") is defined as follows: as a set, it consists of where is an arbitrary vector in The sum of two such elements and is and scalar multiplication is given by The key point in this definition is that if and only if the difference of and lies in This way, the quotient space "forgets" information that is contained in the subspace

The kernel of a linear map consists of vectors that are mapped to in The kernel and the image are subspaces of and respectively. The existence of kernels and images is part of the statement that the category of vector spaces (over a fixed field ) is an abelian category, that is, a corpus of mathematical objects and structure-preserving maps between them (a category) that behaves much like the category of abelian groups. Because of this, many statements such as the first isomorphism theorem (also called rank–nullity theorem in matrix-related terms)

An important example is the kernel of a linear map for some fixed matrix as above. The kernel of this map is the subspace of vectors such that which is precisely the set of solutions to the system of homogeneous linear equations belonging to This concept also extends to linear differential equations

Direct product and direct sum

The direct product of vector spaces and the direct sum of vector spaces are two ways of combining an indexed family of vector spaces into a new vector space.

The direct product of a family of vector spaces consists of the set of all tuples which specify for each index in some index set an element of Addition and scalar multiplication is performed componentwise. A variant of this construction is the direct sum (also called coproduct and denoted ), where only tuples with finitely many nonzero vectors are allowed. If the index set is finite, the two constructions agree, but in general they are different.

Tensor product

The tensor product or simply of two vector spaces and is one of the central notions of multilinear algebra which deals with extending notions such as linear maps to several variables. A map from the Cartesian product is called bilinear if is linear in both variables and That is to say, for fixed the map is linear in the sense above and likewise for fixed

The tensor product is a particular vector space that is a universal recipient of bilinear maps as follows. It is defined as the vector space consisting of finite (formal) sums of symbols called tensors

Vector spaces with additional structure

From the point of view of linear algebra, vector spaces are completely understood insofar as any vector space over a given field is characterized, up to isomorphism, by its dimension. However, vector spaces per se do not offer a framework to deal with the question—crucial to analysis—whether a sequence of functions converges to another function. Likewise, linear algebra is not adapted to deal with infinite series, since the addition operation allows only finitely many terms to be added. Therefore, the needs of functional analysis require considering additional structures.

A vector space may be given a partial order under which some vectors can be compared. For example, -dimensional real space can be ordered by comparing its vectors componentwise. Ordered vector spaces, for example Riesz spaces, are fundamental to Lebesgue integration, which relies on the ability to express a function as a difference of two positive functions

Normed vector spaces and inner product spaces

"Measuring" vectors is done by specifying a norm, a datum which measures lengths of vectors, or by an inner product, which measures angles between vectors. Norms and inner products are denoted and respectively. The datum of an inner product entails that lengths of vectors can be defined too, by defining the associated norm Vector spaces endowed with such data are known as normed vector spaces and inner product spaces, respectively.

Coordinate space can be equipped with the standard dot product:

Topological vector spaces

Convergence questions are treated by considering vector spaces carrying a compatible topology, a structure that allows one to talk about elements being close to each other. Compatible here means that addition and scalar multiplication have to be continuous maps. Roughly, if and in and in vary by a bounded amount, then so do and To make sense of specifying the amount a scalar changes, the field also has to carry a topology in this context; a common choice are the reals or the complex numbers.

In such topological vector spaces one can consider series of vectors. The infinite sum

A way to ensure the existence of limits of certain infinite series is to restrict attention to spaces where any Cauchy sequence has a limit; such a vector space is called complete. Roughly, a vector space is complete provided that it contains all necessary limits. For example, the vector space of polynomials on the unit interval equipped with the topology of uniform convergence is not complete because any continuous function on can be uniformly approximated by a sequence of polynomials, by the Weierstrass approximation theorem. In contrast, the space of all continuous functions on with the same topology is complete. A norm gives rise to a topology by defining that a sequence of vectors converges to if and only if

From a conceptual point of view, all notions related to topological vector spaces should match the topology. For example, instead of considering all linear maps (also called functionals) maps between topological vector spaces are required to be continuous. In particular, the (topological) dual space consists of continuous functionals (or to ). The fundamental Hahn–Banach theorem is concerned with separating subspaces of appropriate topological vector spaces by continuous functionals.

Banach spaces

Banach spaces, introduced by Stefan Banach, are complete normed vector spaces.

A first example is the vector space consisting of infinite vectors with real entries whose -norm given by

The topologies on the infinite-dimensional space are inequivalent for different For example, the sequence of vectors in which the first components are and the following ones are converges to the zero vector for but does not for

More generally than sequences of real numbers, functions are endowed with a norm that replaces the above sum by the Lebesgue integral

The space of integrable functions on a given domain (for example an interval) satisfying and equipped with this norm are called Lebesgue spaces, denoted

These spaces are complete. (If one uses the Riemann integral instead, the space is not complete, which may be seen as a justification for Lebesgue's integration theory.) Concretely this means that for any sequence of Lebesgue-integrable functions with satisfying the condition

Imposing boundedness conditions not only on the function, but also on its derivatives leads to Sobolev spaces.

Hilbert spaces

Complete inner product spaces are known as Hilbert spaces, in honor of David Hilbert. The Hilbert space with inner product given by

By definition, in a Hilbert space any Cauchy sequence converges to a limit. Conversely, finding a sequence of functions with desirable properties that approximates a given limit function, is equally crucial. Early analysis, in the guise of the Taylor approximation, established an approximation of differentiable functions by polynomials. By the Stone–Weierstrass theorem, every continuous function on can be approximated as closely as desired by a polynomial. A similar approximation technique by trigonometric functions is commonly called Fourier expansion, and is much applied in engineering, see below. More generally, and more conceptually, the theorem yields a simple description of what "basic functions", or, in abstract Hilbert spaces, what basic vectors suffice to generate a Hilbert space in the sense that the closure of their span (that is, finite linear combinations and limits of those) is the whole space. Such a set of functions is called a basis of its cardinality is known as the Hilbert space dimension. Not only does the theorem exhibit suitable basis functions as sufficient for approximation purposes, but also together with the Gram–Schmidt process, it enables one to construct a basis of orthogonal vectors. Such orthogonal bases are the Hilbert space generalization of the coordinate axes in finite-dimensional Euclidean space.

The solutions to various differential equations can be interpreted in terms of Hilbert spaces. For example, a great many fields in physics and engineering lead to such equations and frequently solutions with particular physical properties are used as basis functions, often orthogonal. As an example from physics, the time-dependent Schrödinger equation in quantum mechanics describes the change of physical properties in time by means of a partial differential equation, whose solutions are called wavefunctions. Definite values for physical properties such as energy, or momentum, correspond to eigenvalues of a certain (linear) differential operator and the associated wavefunctions are called eigenstates. The spectral theorem decomposes a linear compact operator acting on functions in terms of these eigenfunctions and their eigenvalues.

Algebras over fields

General vector spaces do not possess a multiplication between vectors. A vector space equipped with an additional bilinear operator defining the multiplication of two vectors is an algebra over a field. Many algebras stem from functions on some geometrical object: since functions with values in a given field can be multiplied pointwise, these entities form algebras. The Stone–Weierstrass theorem, for example, relies on Banach algebras which are both Banach spaces and algebras.

Commutative algebra makes great use of rings of polynomials in one or several variables, introduced above. Their multiplication is both commutative and associative. These rings and their quotients form the basis of algebraic geometry, because they are rings of functions of algebraic geometric objects.

Another crucial example are Lie algebras, which are neither commutative nor associative, but the failure to be so is limited by the constraints ( denotes the product of and ):

- (anticommutativity), and

- (Jacobi identity).

Examples include the vector space of -by- matrices, with the commutator of two matrices, and endowed with the cross product.

The tensor algebra is a formal way of adding products to any vector space to obtain an algebra. As a vector space, it is spanned by symbols, called simple tensors

When a field, is explicitly stated, a common term used is -algebra.

Related structures

Vector bundles

A vector bundle is a family of vector spaces parametrized continuously by a topological space X. More precisely, a vector bundle over X is a topological space E equipped with a continuous map

Properties of certain vector bundles provide information about the underlying topological space. For example, the tangent bundle consists of the collection of tangent spaces parametrized by the points of a differentiable manifold. The tangent bundle of the circle S1 is globally isomorphic to S1 × R, since there is a global nonzero vector field on S1. In contrast, by the hairy ball theorem, there is no (tangent) vector field on the 2-sphere S2 which is everywhere nonzero. K-theory studies the isomorphism classes of all vector bundles over some topological space. In addition to deepening topological and geometrical insight, it has purely algebraic consequences, such as the classification of finite-dimensional real division algebras: R, C, the quaternions H and the octonions O.

The cotangent bundle of a differentiable manifold consists, at every point of the manifold, of the dual of the tangent space, the cotangent space. Sections of that bundle are known as differential one-forms.

Modules

Modules are to rings what vector spaces are to fields: the same axioms, applied to a ring R instead of a field F, yield modules. The theory of modules, compared to that of vector spaces, is complicated by the presence of ring elements that do not have multiplicative inverses. For example, modules need not have bases, as the Z-module (that is, abelian group) Z/2Z shows; those modules that do (including all vector spaces) are known as free modules. Nevertheless, a vector space can be compactly defined as a module over a ring which is a field, with the elements being called vectors. Some authors use the term vector space to mean modules over a division ring. The algebro-geometric interpretation of commutative rings via their spectrum allows the development of concepts such as locally free modules, the algebraic counterpart to vector bundles.

Affine and projective spaces

Roughly, affine spaces are vector spaces whose origins are not specified. More precisely, an affine space is a set with a free transitive vector space action. In particular, a vector space is an affine space over itself, by the map

The set of one-dimensional subspaces of a fixed finite-dimensional vector space V is known as projective space; it may be used to formalize the idea of parallel lines intersecting at infinity. Grassmannians and flag manifolds generalize this by parametrizing linear subspaces of fixed dimension k and flags of subspaces, respectively.

Related concepts

- Specific vectors in a vector space

- Zero vector (sometimes also called null vector and denoted by ), the additive identity in a vector space. In a normed vector space, it is the unique vector of norm zero. In a Euclidean vector space, it is the unique vector of length zero.

- Basis vector, an element of a given basis of a vector space.

- Unit vector, a vector in a normed vector space whose norm is 1, or a Euclidean vector of length one.

- Isotropic vector or null vector, in a vector space with a quadratic form, a non-zero vector for which the form is zero. If a null vector exists, the quadratic form is said an isotropic quadratic form.

- Vectors in specific vector spaces

- Column vector, a matrix with only one column. The column vectors with a fixed number of rows form a vector space.

- Row vector, a matrix with only one row. The row vectors with a fixed number of columns form a vector space.

- Coordinate vector, the n-tuple of the coordinates of a vector on a basis of n elements. For a vector space over a field F, these n-tuples form the vector space (where the operation are pointwise addition and scalar multiplication).

- Displacement vector, a vector that specifies the change in position of a point relative to a previous position. Displacement vectors belong to the vector space of translations.

- Position vector of a point, the displacement vector from a reference point (called the origin) to the point. A position vector represents the position of a point in a Euclidean space or an affine space.

- Velocity vector, the derivative, with respect to time, of the position vector. It does not depend of the choice of the origin, and, thus belongs to the vector space of translations.

- Pseudovector, also called axial vector

- Covector, an element of the dual of a vector space. In an inner product space, the inner product defines an isomorphism between the space and its dual, which may make difficult to distinguish a covector from a vector. The distinction becomes apparent when one changes coordinates (non-orthogonally).

- Tangent vector, an element of the tangent space of a curve, a surface or, more generally, a differential manifold at a given point (these tangent spaces are naturally endowed with a structure of vector space)

- Normal vector or simply normal, in a Euclidean space or, more generally, in an inner product space, a vector that is perpendicular to a tangent space at a point.

- Gradient, the coordinates vector of the partial derivatives of a function of several real variables. In a Euclidean space the gradient gives the magnitude and direction of maximum increase of a scalar field. The gradient is a covector that is normal to a level curve.

- Four-vector, in the theory of relativity, a vector in a four-dimensional real vector space called Minkowski space

![{\displaystyle [0,1],}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/971caee396752d8bf56711f55d2c3b1207d4a236)

![[0,1]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/738f7d23bb2d9642bab520020873cccbef49768d)

![[a,b]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9c4b788fc5c637e26ee98b45f89a5c08c85f7935)

![{\displaystyle \mathbf {R} [x,y]/(x\cdot y-1),}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/7ba7424ec2e6bf0fc108cb223ae2d6209c67b44d)

![[x,y]](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/1b7bd6292c6023626c6358bfd3943a031b27d663)

![{\displaystyle [x,y]=-[y,x]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/f70fcda86c14de45e211c3a9a889845038bb7348)

![{\displaystyle [x,[y,z]]+[y,[z,x]]+[z,[x,y]]=0}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/23655a62f2a7cc545f121d9bcc30fe2c56731457)

![{\displaystyle [x,y]=xy-yx,}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/8c9d7bc98d1738f549c0420244c08c57decc66b3)