| Back pain | |

|---|---|

| |

| Different regions (curvatures) of the vertebral column |

Back pain (Latin: dorsalgia) is pain felt in the back. It may be classified as neck pain (cervical), middle back pain (thoracic), lower back pain (lumbar) or coccydynia (tailbone or sacral pain) based on the segment affected. The lumbar area is the most common area affected. An episode of back pain may be acute, subacute or chronic depending on the duration. The pain may be characterized as a dull ache, shooting or piercing pain or a burning sensation. Discomfort can radiate to the arms and hands as well as the legs or feet, and may include numbness or weakness in the legs and arms.

The majority of back pain is nonspecific and idiopathic. Common underlying mechanisms include degenerative or traumatic changes to the discs and facet joints, which can then cause secondary pain in the muscles and nerves and referred pain to the bones, joints and extremities. Diseases and inflammation of the gallbladder, pancreas, aorta and kidneys may also cause referred pain in the back. Tumors of the vertebrae, neural tissues and adjacent structures can also manifest as back pain.

Back pain is common; approximately nine of ten adults experience it at some point in their lives, and five of ten working adults experience back pain each year. Some estimate that as many of 95% of people will experience back pain at some point in their lifetime. It is the most common cause of chronic pain and is a major contributor to missed work and disability. For most individuals, back pain is self-limiting. Most people with back pain do not experience chronic severe pain but rather persistent or intermittent pain that is mild or moderate. In most cases of herniated disks and stenosis, rest, injections or surgery have similar general pain-resolution outcomes on average after one year. In the United States, acute low back pain is the fifth most common reason for physician visits and causes 40% of missed work days. It is the single leading cause of disability worldwide.

Classification

Back pain is classified in terms of duration of symptoms.

- Acute back pain lasts <6 weeks

- Subacute back pain lasts between 6 and 12 weeks.

- Chronic back pain lasts for greater than 12 weeks.

Causes

There are many causes of back pain, including blood vessels, internal organs, infections, mechanical and autoimmune causes. Approximately 90 percent of people with back pain are diagnosed with nonspecific, idiopathic acute pain with no identifiable underlying pathology. In approximately 10 percent of people, a cause can be identified through diagnostic imaging. Fewer than two percent of cases are attributed to secondary factors, with metastatic cancers and serious infections, such as spinal osteomyelitis and epidural abscesses, accounting for approximately one percent.

| Cause | % of people with back pain |

|---|---|

| Nonspecific | 90% |

| Vertebral compression fracture | 4% |

| Metastatic cancer | 0.7% |

| Infection | 0.01% |

| Cauda equina | 0.04% |

Nonspecific

In as many as 90 percent of cases, no physiological causes or abnormalities on diagnostic tests can be found. Nonspecific back pain can result from back strain or sprains, which can cause peripheral injury to muscle or ligaments. Many patients cannot identify the events or activities that may have caused the strain. The pain can present acutely but in some cases can persist, leading to chronic pain.

Chronic back pain in people with otherwise normal scans can result from central sensitization, in which an initial injury causes a longer-lasting state of heightened sensitivity to pain. This persistent state maintains pain even after the initial injury has healed. Treatment of sensitization may involve low doses of antidepressants and directed rehabilitation such as physical therapy.

Spinal disc disease

Spinal disc disease occurs when the nucleus pulposus, a gel-like material in the inner core of the vertebral disc, ruptures. Rupturing of the nucleus pulposus can lead to compression of nerve roots. Symptoms may be unilateral or bilateral, and correlate to the region of the spine affected. The most common region for spinal disk disease is at L4–L5 or L5–S1. The risk for lumbar disc disease is increased in overweight individuals because of the increased compressive force on the nucleus pulposus, and is twice as likely to occur in men. A 2002 study found that lifestyle factors such as night-shift work and lack of physical activity can also increase the risk of lumbar disc disease.

Severe spinal-cord compression is considered a surgical emergency and requires decompression to preserve motor and sensory function. Cauda equina syndrome involves severe compression of the cauda equina and presents initially with pain followed by motor and sensory. Bladder incontinence is seen in later stages of cauda equina syndrome.

Degenerative disease

Spondylosis, or degenerative arthritis of the spine, occurs when the intervertebral disc undergoes degenerative changes, causing the disc to fail at cushioning the vertebrae. There is an association between intervertebral disc space narrowing and lumbar spine pain. The space between the vertebrae becomes more narrow, resulting in compression and irritation of the nerves.

Spondylolithesis is the anterior shift of one vertebra compared to the neighboring vertebra. It is associated with age-related degenerative changes as well as trauma and congenital anomalies.

Spinal stenosis can occur in cases of severe spondylosis, spondylotheisis and age-associated thickening of the ligamentum flavum. Spinal stenosis involves narrowing of the spinal canal and typically presents in patients greater than 60 years of age. Neurogenic claudication can occur in cases of severe lumbar spinal stenosis and presents with symptoms of pain in the lower back, buttock or leg that is worsened by standing and relieved by sitting.

Vertebral compression fractures occur in four percent of patients presenting with lower back pain. Risk factors include age, female gender, history of osteoporosis, and chronic glucocorticoid use. Fractures can occur as a result of trauma but in many cases can be asymptomatic.

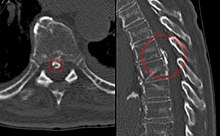

Infection

Common infectious causes of back pain include osteomyelitis, septic discitis, paraspinal abscess and epidural abscess. Infectious causes that lead to back pain involve various structures surrounding the spine.

Osteomyelitis is the bacterial infection of the bone. Vertebral osteomyelitis is most commonly caused by staphylococci. Risk factors include skin infection, urinary tract infection, IV catheter use, IV drug use, previous endocarditis and lung disease.

Spinal epidural abscess is commonly caused by severe infection with bacteremia. Risk factors include recent administration of epidurals, IV drug use or recent infection.

Cancer

Spread of cancer to the bone or spinal cord can lead to back pain. Bone is one of the most common sites of metastatic lesions. Patients typically have a history of malignancy. Common types of cancer that present with back pain include multiple myeloma, lymphoma, leukemia, spinal cord tumors, primary vertebral tumors and prostate cancer. Back pain is present in 29% of patients with systemic cancer. Unlike other causes of back pain that commonly affect the lumbar spine, the thoracic spine is most commonly affected. The pain can be associated with systemic symptoms such as weight loss, chills, fever, nausea and vomiting. Unlike other causes of back pain, neoplasm-associated back pain is constant, dull, poorly localized and worsens with rest. Metastasis to the bone also increases the risk of spinal-cord compression or vertebral fractures that require emergency surgical treatment.

Autoimmune

Inflammatory arthritides such as ankylosing spondylitis, psoriatic arthritis, rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus can all cause varying levels of joint destruction. Among the inflammatory arthritides, ankylosing spondylitis is most closely associated with back pain because of the inflammatory destruction of the bony components of the spine. Ankylosing spondylitis is common in young men and presents with a range of possible symptoms such as uveitis, psoriasis and inflammatory bowel disease.

Referred pain

Back pain can also be referred from another source. Referred pain occurs when pain is felt at a location different than the source of the pain. Disease processes that can present with back pain include pancreatitis, kidney stones, severe urinary tract infections and abdominal aortic aneurysms.

Risk factors

Heavy lifting, obesity, sedentary lifestyle and lack of exercise can increase the risk of back pain. Cigarette smokers are more likely to experience back pain than are nonsmokers. Weight gain in pregnancy is also a risk factor for back pain. In general, fatigue can worsen pain.

A few studies suggest that psychosocial factors such as work-related stress and dysfunctional family relationships may correlate more closely with back pain than do structural abnormalities revealed in X-rays and other medical imaging scans.

Back pain physical effects can range from muscle aching to a shooting, burning, or stabbing sensation. Pain can radiate down the legs and can be increased by bending, twisting, lifting, standing, or walking. While the physical effects of back pain are always at the forefront, back pain also can have psychological effects. Back pain has been linked to depression, anxiety, stress, and avoidance behaviors due to mentally not being able to cope with the physical pain. Both acute and chronic back pain can be associated with psychological distress in the form of anxiety (worries, stress) or depression (sadness, discouragement). Psychological distress is a common reaction to the suffering aspects of acute back pain, even when symptoms are short-term and not medically serious.

Diagnosis

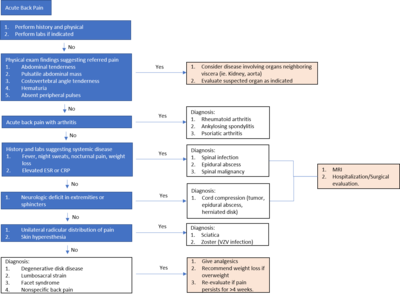

Initial assessment of back pain consists of a history and physical examination. Important characterizing features of back pain include location, duration, severity, history of prior back pain and possible trauma. Other important components of the patient history include age, physical trauma, prior history of cancer, fever, weight loss, urinary incontinence, progressive weakness or expanding sensory changes, which can indicate a medically urgent condition.

Physical examination of the back should assess for posture and deformities. Pain elicited by palpating certain structures may be helpful in localizing the affected area. A neurologic exam is needed to assess for changes in gait, sensation and motor function.

Determining if there are radicular symptoms, such as pain, numbness or weakness that radiate down limbs, is important for differentiating between central and peripheral causes of back pain. The straight leg test is a maneuver used to determine the presence of lumbosacral radiculopathy, which occurs when there is irritation in the nerve root that causes neurologic symptoms such as numbness and tingling. Non-radicular back pain is most commonly caused by injury to the spinal muscles or ligaments, degenerative spinal disease or a herniated disc. Disc herniation and foraminal stenosis are the most common causes of radiculopathy.

Imaging of the spine and laboratory tests is not recommended during the acute phase. This assumes that there is no reason to expect that the patient has an underlying problem. In most cases, the pain subsides naturally after several weeks. People who seek diagnosis through imaging are typically less likely to receive a better outcome than are those who wait for the condition to resolve.

Imaging

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the preferred modality for the evaluation of back pain and visualization of bone, soft tissue, nerves and ligaments. X-rays are a less costly initial option offered to patients with a low clinical suspicion of infection or malignancy, and they are combined with laboratory studies for interpretation.

Imaging is not warranted for most patients with acute back pain. Without signs and symptoms indicating a serious underlying condition, imaging does not improve clinical outcomes in these patients. Four to six weeks of treatment is appropriate before consideration of imaging studies. If a serious condition is suspected, MRI is usually most appropriate. Computed tomography is an alternative if MRI is contraindicated or unavailable. In cases of acute back pain, MRI is recommended for those with major risk factors or clinical suspicion of cancer, spinal infection or severe progressive neurological deficits. For patients with subacute to chronic back pain, MRI is recommended if minor risk factors exist for cancer, ankylosing spondylitis or vertebral compression fracture, or if significant trauma or symptomatic spinal stenosis is present.

Early imaging studies during the acute phase do not improve care or prognosis. Imaging findings are not correlated with severity or outcome.

Laboratory studies

Laboratory studies are employed when there are suspicions of autoimmune causes, infection or malignancy. Laboratory testing may include white blood cell (WBC) count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), and C-reactive protein (CRP).

- Elevated ESR could indicate infection, malignancy, chronic disease, inflammation, trauma or tissue ischemia.

- Elevated CRP levels are associated with infection.

Because laboratory testing lacks specificity, MRI with and without contrast media and often, biopsy are essential for accurate diagnosis

Red flags

Imaging is not typically needed in the initial diagnosis or treatment of back pain. However, if there are certain "red flag" symptoms present, plain radiographs (X-ray), CT scan or magnetic resonance imaging may be recommended. These red flags include:

- History of cancer

- Unexplained weight loss

- Immunosuppression

- Urinary infection

- Intravenous drug use

- Prolonged use of corticosteroids

- Back pain not improved with conservative management

- History of significant trauma

- Minor fall or heavy lift in a potentially osteoporotic or elderly individual

- Acute onset of urinary retention, overflow incontinence, loss of anal sphincter tone, or fecal incontinence

- Saddle anesthesia

- Global or progressive motor weakness in the lower limbs

Prevention

Moderate-quality evidence exists that suggests that the combination of education and exercise may reduce an individual's risk of developing an episode of low back pain. Lesser-quality evidence points to exercise alone as a possible deterrent to the risk of the condition.

Management

Nonspecific pain

Patients with uncomplicated back pain should be encouraged to remain active and to return to normal activities.

The management goals when treating back pain are to achieve maximal reduction in pain intensity as rapidly as possible, to restore the individual's ability to function in everyday activities, to help the patient cope with residual pain, to assess for side effects of therapy and to facilitate the patient's passage through the legal and socioeconomic impediments to recovery. For many, the goal is to keep the pain at a manageable level to progress with rehabilitation, which then can lead to long-term pain relief. Also, for some people the goal is to use nonsurgical therapies to manage the pain and avoid major surgery, while for others surgery may represent the quickest path to pain relief.

Not all treatments work for all conditions or for all individuals with the same condition, and many must try several treatment options to determine what works best for them. The present stage of the condition (acute or chronic) is also a determining factor in the choice of treatment. Only a minority of people with back pain (most estimates are 1–10%) require surgery.

Nonmedical

Back pain is generally first treated with nonpharmacological therapy, as it typically resolves without the use of medication. Superficial heat and massage, acupuncture and spinal manipulation therapy may be recommended.

- Heat therapy is useful for back spasms or other conditions. A review concluded that heat therapy can reduce symptoms of acute and subacute low-back pain.

- Regular activity and gentle stretching exercises is encouraged in uncomplicated back pain and is associated with better long-term outcomes. Physical therapy to strengthen the muscles in the abdomen and around the spine may also be recommended. These exercises are associated with better patient satisfaction, although they have not been shown to provide functional improvement. However, one review found that exercise is effective for chronic back pain but not for acute pain. Exercise should be performed under the supervision of a healthcare professional.

- Massage therapy may provide short-term pain relief, but not functional improvement, for those with acute lower back pain. It may also offer short-term pain relief and functional improvement for those with long-term (chronic) and subacute lower pack pain, but this benefit does not appear to be sustained after six months of treatment. There do not appear to be any serious adverse effects associated with massage.

- Acupuncture may provide some relief for back pain. However, further research with stronger evidence is needed.

- Spinal manipulation appears to provide similar effects to other recommended treatments for chronic low back pain. There is no evidence it is more effective than other therapies or sham, or as an adjunct to other treatments, for acute low back pain

- "Back school" is an intervention that consists of both education and physical exercises.There is no strong evidence supporting the use of back school for treating acute, subacute, or chronic non-specific back pain.

- Insoles appear to be an ineffective treatment intervention.

- While traction for back pain is often used in combination with other approaches, there appears to be little or no impact on pain intensity, functional status, global improvement or return to work.

Medication

If nonpharmacological measures are ineffective, medication may be administered.

- Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) are typically attempted first. NSAIDs have been proven more effective than placebo, and are usually more effective than paracetamol (acetaminophen).

- Long-term use of opioids has not been tested to determine whether it is effective or safe for treating chronic lower back pain. For severe back pain not relieved by NSAIDs or acetaminophen, opioids may be used. Opioids may not be better than NSAIDs or antidepressants for chronic back pain with regard to pain relief and gain of function.

- Skeletal muscle relaxers may also be used. Their short-term use has been proven effective in the relief of acute back pain. However, the evidence of this effect has been disputed, and these medications do have negative side effects.

- For patients with nerve root pain and acute radiculopathy, there is evidence that a single dose of steroids, such as dexamethasone, may provide pain relief.

- Epidural corticosteroid injection (ESI) is a procedure in which steroid medications are injected into the epidural space. The steroid medications reduce inflammation and thus decrease pain and improve function. ESI has long been used to both diagnose and treat back pain, although recent studies have shown a lack of efficacy in treating low back pain.

Surgery

Surgery for back pain is typically used as a last resort, when serious neurological deficit is evident. A 2009 systematic review of back surgery studies found that, for certain diagnoses, surgery is moderately better than other common treatments, but the benefits of surgery often decline in the long term.

Surgery may sometimes be appropriate for people with severe myelopathy or cauda equina syndrome. Causes of neurological deficits can include spinal disc herniation, spinal stenosis, degenerative disc disease, tumor, infection, and spinal hematomas, all of which can impinge on the nerve roots around the spinal cord. There are multiple surgical options to treat back pain, and these options vary depending on the cause of the pain.

When a herniated disc is compressing the nerve roots, hemi- or partial-laminectomy or discectomy may be performed, in which the material compressing on the nerve is removed. A mutli-level laminectomy can be done to widen the spinal canal in the case of spinal stenosis. A foraminotomy or foraminectomy may also be necessary, if the vertebrae are causing significant nerve root compression. A discectomy is performed when the intervertebral disc has herniated or torn. It involves removing the protruding disc, either a portion of it or all of it, that is placing pressure on the nerve root. Total disc replacement can also be performed, in which the source of the pain (the damaged disc) is removed and replaced, while maintaining spinal mobility. When an entire disc is removed (as in discectomy), or when the vertebrae are unstable, spinal fusion surgery may be performed. Spinal fusion is a procedure in which bone grafts and metal hardware is used to fix together two or more vertebrae, thus preventing the bones of the spinal column from compressing on the spinal cord or nerve roots.

If infection, such as a spinal epidural abscess, is the source of the back pain, surgery may be indicated when a trial of antibiotics is ineffective. Surgical evacuation of spinal hematoma can also be attempted, if the blood products fail to break down on their own.

Pregnancy

About 50% of women experience low back pain during pregnancy. Some studies have suggested that women who have experienced back pain before pregnancy are at a higher risk of experiencing back pain during pregnancy. It may be severe enough to cause significant pain and disability in as many as one third of pregnant women. Back pain typically begins at approximately 18 weeks of gestation and peaks between 24 and 36 weeks. Approximately 16% of women who experience back pain during pregnancy report continued back pain years after pregnancy, indicating that those with significant back pain are at greater risk of back pain following pregnancy.

Biomechanical factors of pregnancy shown to be associated with back pain include increased curvature of the lower back, or lumbar lordosis, to support the added weight on the abdomen. Also, the hormone relaxin is released during pregnancy, which softens the structural tissues in the pelvis and lower back to prepare for vaginal delivery. This softening and increased flexibility of the ligaments and joints in the lower back can result in pain. Back pain in pregnancy is often accompanied by radicular symptoms, suggested to be caused by the baby pressing on the sacral plexus and lumbar plexus in the pelvis.

Typical factors aggravating the back pain of pregnancy include standing, sitting, forward bending, lifting and walking. Back pain in pregnancy may also be characterized by pain radiating into the thigh and buttocks, nighttime pain severe enough to wake the patient, pain that is increased at night or pain that is increased during the daytime.

Local heat, acetaminophen (paracetamol) and massage can be used to help relieve pain. Avoiding standing for prolonged periods of time is also suggested.