This article details the geographical distribution of speakers of the German language, regardless of the legislative status within the countries where it is spoken. In addition to the Germanosphere (German: Deutscher Sprachraum) in Europe, German-speaking minorities are present in many other countries and on all six inhabited continents.

Mostly depending on the inclusion or exclusion of certain varieties with a disputed status as separate languages or which were later acknowledged as separate languages (e.g., Low German/Plautdietsch), it is estimated that approximately 90–95 million people speak German as a first language, 10–25 million as a second language, and 75–100 million as a foreign language. This would imply approximately 175–220 million German speakers worldwide.

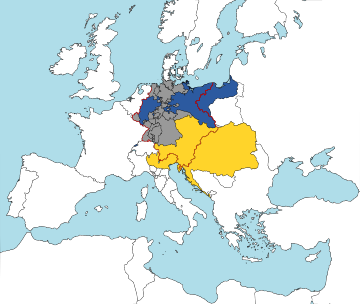

Europe

German-speaking Europe

Approximate distribution of native German speakers (assuming a rounded total of 95 million) worldwide:

The German language is spoken in a number of countries and territories in Europe, where it is used both as an official language and as a minority language in various countries. To cover this language area, they are often referred to as the German-speaking countries, the German-speaking area (Deutscher Sprachraum), or equivalently German-speaking Europe (non-European German-speaking communities are not commonly included in the concept).

German is the main language of approximately 95 to 100 million people in Europe, or 13.3% of all Europeans. This makes it the second most spoken native language in Europe, behind only Russian (with 144 million speakers), and ahead of French (with 66.5 million) and English (with 64.2 million).

The European countries with German-speaking majorities are Germany (95%, 78.3 million), Austria (89%, 8.9 million), and Switzerland (65%, 4.6 million), also known as the "D-A-CH" countries, an acronym for Deutschland (Germany), Austria, and Confoederatio Helvetica (the Swiss Confederation).

Since 2004, there has been an annual informal meeting of the heads of state of German-speaking countries including the Presidents of Germany, Austria, and Switzerland and the Hereditary Prince of Liechtenstein. Since 2014, the King of Belgium and the Grand Duke of Luxembourg have taken part.

D-A-CH or DACH is an acronym used to represent the dominant states of the German language Sprachraum. It is based on the international vehicle registration codes for:

- Germany (D for Deutschland)

- Austria (A for Austria, in German "Österreich")

- Switzerland (CH for Confoederatio Helvetica, in German "(die) Schweiz")

"Dach" is also the German word for "roof", and is used in linguistics in the term Dachsprache, which standard German arguably is in relation to some outlying dialects of German, especially in Switzerland, France, Luxembourg, and Austria.

The term is sometimes extended to D-A-CH-Li, DACHL, or DACH+ to include Liechtenstein. Another version is DACHS (with Dachs meaning "Badger" in German) with the inclusion of the German-speaking region of South Tyrol in Italy.

DACH is also the name of an Interreg IIIA project, which focuses on crossborder cooperation in planning.

Rest of Europe

In the early modern period, German varieties were a lingua franca of Central, Eastern, and Northern Europe (Hanseatic League).

German is a recognised minority language in Czechia, Hungary, Italy (Trentino-Alto Adige/Südtirol), Poland, Romania, Russia, and Slovakia.

Today German, together with French, is a common second foreign language in the western world, with English well established as a first foreign language. German ranks second (after English) among the best known foreign languages in the EU (on a par with French) as well as in Russia. In terms of student numbers across all levels of education, German ranks third in the EU (after English and French) as well as in the United States (after Spanish and French). In 2015, approximately 15.4 million people were in the process of learning German across all levels of education worldwide. This number has remained relatively stable since 2005 (± 1 million) and roughly 75–100 million people able to communicate in German as a foreign language can be inferred, assuming an average course duration of three years and other estimated parameters. According to a 2012 survey, ca. 47 million people within the EU (i.e., up to two thirds of the 75–100 million worldwide) claimed to have sufficient German skills to have a conversation. Within the EU, and not counting countries where it is a (co-)official language, German as a foreign language is most widely taught in Central and Northern Europe, namely Croatia, the Czech Republic, Denmark, the Netherlands, Poland, Slovakia, Slovenia, and Sweden.

German as a foreign language is promoted by the Goethe Institute, which works to promote German language and culture worldwide. In association with the Goethe Institute, the German foreign broadcasting service, Deutsche Welle, offers a range of online German courses and worldwide television as well as radio broadcasts produced with non-native German speakers in mind.

-

Self-reported German language skills of European Union citizens (2010)

Africa

Namibia

Namibia was a colony of the German Empire from 1884 to 1915. Mostly originating from Germans who settled there during this time, 25,000 to 30,000 people still speak German as a native tongue today. German, along with English and Afrikaans used to be a co-official language of Namibia from 1984 until its independence from South Africa in 1990. At this point, the Namibian government perceived Afrikaans and German as symbols for Apartheid and colonialism, and decided for English to be the sole official language, claiming that it was a "neutral" language as virtually no English native speakers existed in Namibia at that time. German, Afrikaans and several indigenous languages became "national languages" by law, identifying them as cultural heritages of the nation and ensuring the state to acknowledge and support their presence in the country. Today, German is used in myriad spheres, especially business and tourism, as well as churches (most notably the German-speaking Evangelical Lutheran Church in Namibia (GELK)), schools (e.g., the Deutsche Höhere Privatschule Windhoek), literature (German-Namibian authors include Giselher W. Hoffmann), radio (the Namibian Broadcasting Corporation produces radio programs in German), and music (e.g., artist EES). The Allgemeine Zeitung is also one of the three biggest newspapers in Namibia and the only German-language daily in Africa.

South Africa

Mostly originating from different waves of immigration during the 19th and 20th centuries, an estimated 12,000 people speak German or a German variety as a first language in South Africa. Germans settled quite extensively in South Africa, with many Calvinists immigrating from Northern Europe. Later on, more Germans settled in the KwaZulu-Natal region and elsewhere. Here, one of the largest communities are the speakers of "Nataler Deutsch", a variety of Low German, who are concentrated in and around Wartburg and to a lesser extent around Winterton. German is slowly disappearing elsewhere, but a number of communities still have a large number of speakers and some even have German language schools, such as the Hermannsburg German School. Furthermore, German was often a language taught as a foreign language in White South African schools during the Apartheid years (1948–1994). Today, the South African constitution identifies German as a "commonly used" language and the Pan South African Language Board is obligated to promote and ensure respect for it.

Americas

Latin America

Nowadays, at least one million German speakers live in Latin America. There are German-speaking minorities in almost every Latin American country, including Argentina, Belize, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, the Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, Nicaragua, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela.

Initially, in the eighteenth century, only isolated or small groups of German emigrants left for Latin America; however, at the start of the nineteenth, this pattern was reversed as a tidal wave of German emigration totaling some 200,000 people began. These included groups such as land-hungry peasants, political refugees known as Forty-Eighters, and religious minorities such as Russian Mennonites fleeing religious persecution at home. During the 1880s, during the wave of mass emigration, this figure was reached annually.

The Handbuch des Deutschtums im Ausland (The Germans Abroad Handbook) from 1906 puts a figure of 11 million people in North and South America with a knowledge of the German language, of which 9 million were in the US. Although the US was the focal point for emigration in the 19th century, emigration to Latin America was also significant for differing economic and political reasons.

The majority of German emigrants to Latin America went especially to Brazil, but also to Argentina, Mexico, Uruguay, Chile, Paraguay, Guatemala, and Costa Rica. The three countries with the biggest ethnic German populations in Latin America to this day are Brazil, Argentina, and Mexico.

Starting in 1818, when King D. João VI brought the first German and Swiss immigrants to Brazil, German immigration continued a constant flow with an average of 25 to 30 thousand immigrants per decade entering the country since 1818. It peaked in the years following World War I, to around 90 thousand, and again in the 1940s to around 50,000. In the 1880s and 1890s, German emigration to Latin America grew and in some years was the destination of up to 30% of German emigrants.

During the Nazi period which lasted from 1933 to 1945, some 100,000 Jews from Central Europe, the vast majority of which were German-speaking, moved to South America, with 90% of these moving to the Cono Sur or Southern Cone. This ended when the ban on emigration came into effect in 1941, which was roughly also the beginning of the holocaust. From the start of the 20th century until 1946, 80% of Jews lived in Europe; but by the end of World War II this was reduced to 25%. However, after the war over 50% of Jews lived in the Americas. This change was aided by Jewish emigration groups such as the Hilfsverein deutschsprechender Juden (later to become Asociación Filantrópica Israelita) which was based in Buenos Aires, Argentina.

The majority of German minorities in Latin America – as well as elsewhere around the world – experienced a decline in the use of the German language, with the exception of Brazil, where the dialect Riograndenser Hunsrückisch is being taught in schools and in some media, totaling over 200 thousand speakers spread over the Brazilian southern states. The main cause of this decrease is the integration of communities, often originally sheltered, into the dominant society, and as well as the invariable pull of societal assimilation which confronts all immigrant groups.

German migration to colonial Mexico is less accounted for due to the geopolitical isolation following independence from Spain, as well as the deterrents of Mexico's ensuing civil wars. Despite these obstacles and lack of documentation, however, over 200,000 Prussian/German nationals have been registered entering the country between 1860 and 1960.

The first wave of Germans immigrated from northern Prussia under the reign of Princess Carlota during the 2nd French Mexican empire. Of special interest is the settlement Villa Carlota: that was the name under which two German farming settlements, in the villages of Santa Elena and Pustunich in Yucatán, were founded during the Second Mexican Empire (1864–1867). Villa Carlota attracted a total of 443 German-speaking immigrant families, most of them were farmers and artisans who emigrated with their families: the majority came from Prussia and many among them were Protestants.

The second wave was during Porfirio Díaz's open settlement policy in the Yucatán Peninsula that favored and attracted many Europeans. Most German-speaking or self identifying German-Mexicans today are descended from these two events as well as around 20,000 ethnic Germans from Russia and around 100,000 Mennonites from Canada.

Specific reasons for language change from German to the national language usually derive from the desire of many Germans to belong to their new communities after the end of World War II. This is a common feature among the German minorities in Latin America and those in Central and Eastern Europe: the majority of countries where German minorities lived had fought against the Germans during the war. With this change in situation, the members of the German minorities, previously communities of status and prestige, were turned into undesirable minorities (though there were widespread elements of sympathy for Germany in many South American countries as well).

For many German minorities, World War II thus represented the breaking point in the development of their language. In some South American countries the war period and immediately afterwards was a time of massive assimilation to the local culture (for example during the Getúlio Vargas period in Brazil).

Argentina, Brazil, Chile, Mexico, and Paraguay show some clear demographic differences that affect the minority situation of the German language: Brazil, Mexico, and Argentina are massive countries and offer large amounts of land for immigrants to settle. The population density of the Southern Cone countries is relatively low (Brazil has 17 inhabitants/km2, Chile has 15/km2, Argentina and Paraguay both have 10/km2, data from 1993), but there are major differences in the areas settled by Germans: Buenos Aires Province, which was settled by Germans, has a far higher population density than that of the Chaco in northern Paraguay (with 1 inhabitant/km2).

While Argentina and Chile have a far greater proportion of city dwellers (86% and 84% respectively); in contrast, Brazil and Paraguay are 82% and 47% urbanized, respectively. Most of the German immigrants that arrived in Brazil and Mexico went on to live in small inland communities. The original 58 German communities of the early 19th century Brazil, grew today to over 250 towns where Germans are a majority, and German-speaking is encouraged.

Argentina

There are about 500,000 German speakers and around 320,000 Volga-Germans alone, of which 200,000 hold German citizenship. This makes Argentina one of the countries with the largest number of German speakers and is second only in Latin America to Brazil. In the 1930s there were about 700,000 people of German descent. Regional concentrations can be found in the provinces of Entre Ríos and Buenos Aires (with around 500,000 to 600,000) as well as Misiones and in the general area of the Chaco and the Pampas.

However, most German-descended Argentinians do not speak German with native fluency (that role has been taken by Spanish). The 300,000 German speakers are estimated to be immigrants and not actually born in Argentina, and because of this they still speak their home language while their descendants who were born in Argentina speak primarily Spanish.

Brazil

According to Deutsche Welle, there are some twelve million people of German ancestry in Brazil. Nevertheless, the number of people speaking any sort of German (Standard German, Hunsrückisch or East Pomeranian) is on the decrease, with 3 million speaking German as a first language today.

The main variety of German in Brazil is Riograndenser Hunsrückisch which is found in the southern states. This version of German there has changed over 180 years of contact with Portuguese as well as the languages of other immigrant communities. Such contact has led to a new dialect of German concentrated in the German colonies in the southern province of Rio Grande do Sul. Although Riograndenser Hunsrückisch has long been the most widely spoken German dialect in southern Brazil, like all other minority languages in the region, it is experiencing very strong decline – especially in the last three or four decades.

The vast majority of German-descended Brazilians speak Portuguese as their mother tongue today. German is known only as a second or third language, if at all, to the point of initiatives to preserve the language being started recently in areas with strong German-descended presence, with government-sponsored Gemeindeschulen. This is especially true for younger German-Brazilians. Another place where the German language continues alive is in some of the more of 4,000 Brazilian Lutheran churches, in which some of the services continue to be in German.

The German language is co-official in the municipality of Pomerode, besides being cultural patrimony of the State of Espírito Santo. In Rio Grande do Sul, the Riograndenser Hunsrückisch German is an integral part of the State's historical and cultural heritage.

Chile

Chile (with a population of 19 million) has an estimated 40,000 German-speakers. About 30,000 ethnic Germans arrived in Chile. During the first flux of German immigration (between 1846 and 1875) German colonies were primarily set up in the "Frontera" region. The second wave of immigration occurred between 1882 and 1914 and consisted mainly of industrial and agricultural workers, mainly from eastern Germany; the third wave (after 1918) settled mainly in the cities. As in Argentina and Brazil, these populations are today overwhelmingly Spanish speaking, and German as a home language is in heavy decline (The German language is far from disappearing in Chile because there are more than 100 German-language schools throughout the country) German is taught from preschool to middle school; where if German-Chileans can still speak German, most of them speak German only as a second or third language.

Colombia

Colombia has a population of about 51 million people. Of them, only 5,000 people of German descent speak the language. Many of these people settled in Antioquia and el Eje Cafetero. Most of the immigration occurred during World War I until the end of the Cold War. Many of these ethnic Germans now speak primarily Spanish at home.

Germans came to South America in World War I and II, settling first in Colombia because of its wealth in natural resources as well as weather conditions conducive to agriculture. German immigrants built the Bavaria, Pilsen, and Club Soda Klausen factories in Cali, Barranquilla, Pereira, Medellin, and other cities. Nowadays, Germans born in Colombia celebrate Oktoberfest in Cali, along with other traditions. There are currently German schools in various major cities around the country.

Costa Rica

Costa Rica has a population of 4.9 million, and a German-speaking population of 8,000 people. Many of these people are immigrants or native German speakers from Germany or Switzerland and descendants of 18th, 19th and 20th-century mass immigration. But also in the northern area of the country, there are 2,200 German Mennonites in communities in Sarapiquí and San Carlos that spoke Plautdietsch and other Low German dialects.

This German-Costa Rican community is one of the most important and biggest collectivities of German speakers in Central America and the Caribbean, and has a lot of cultural and social institutions, churches, farms, business companies and schools.

Mexico

Mexico (with a population of over 120 million) has an estimated 200,000 speakers of standard German either as a first or second language, not counting foreign learned German speakers or the Low-German dialects. Documented immigration of Germans to Mexico began in 1856, though historical research suggest as many as 1.2 million German speaking immigrants arrived in Mexico during the colonial period likely as agricultural laborers.

Due to pro-nationalistic propagation by the federal government which encouraged mixed-race identification, many Mexicans do not know their ancestral origins and demographic numbers of German Mexicans are sourced on recent and limited data. Regardless, Mexico stands as the 3rd country with the largest German community in Latin America, behind Brazil and Argentina. Included in the ethnic German immigration to Mexico is the immigration from Austria, Switzerland, and the French region of Alsace which was part of France since the end of WWI, as well as that from Bavaria and High German regions of Germany.

As of 2012, about 20,000 Germans nationals resided in Mexico. The number has risen to almost 40,000 in 2020. Despite groggy heritage claims to the language, German is slightly ahead of French as the second most studied foreign language in Mexico, behind only English. Mexico is home to over 3,000 German language schools, second only to Brazil. The Colegio Humboldt campuses in Mexico are the biggest German language K-12 schools in the Americas, with each of the 3 branches graduating over 2,000 students per year.

Northern America

Canada

In Canada, there are 622,650 speakers of German according to the most recent census in 2006, with people of German ancestry (German Canadians) found throughout the country. German-speaking communities are particularly found in British Columbia (118,035) and Ontario (230,330). There is a large and vibrant community in the city of Kitchener, Ontario, which was at one point named Berlin. German immigrants were instrumental in the country's three largest urban areas: Montreal, Toronto, and Vancouver. Post-Second World War immigrants managed to preserve a fluency in the German language in their respective neighborhoods and sections. In the first half of the 20th century, over a million German-Canadians made the language Canada's third most spoken after French and English.

United States

In the United States, the states of North Dakota and South Dakota are the only states where German is the most common language spoken at home after English. German geographical names can be found throughout the Midwest region of the country, such as New Ulm and many other towns in Minnesota; Bismarck (North Dakota's state capital), Munich, Karlsruhe, and Strasburg (named after a town near Odesa in Ukraine) in North Dakota; New Braunfels, Fredericksburg, Weimar, and Muenster in Texas; Corn (formerly Korn), Kiefer and Berlin in Oklahoma; and Kiel, Schleswig, Berlin, and Germantown in Wisconsin.

Between 1843 and 1910, more than 5 million Germans emigrated overseas, mostly to the United States. German remained an important language in churches, schools, newspapers, and even the administration of the United States Brewers' Association through the early 20th century, but was severely repressed during World War I. Over the course of the 20th century, many of the descendants of 18th century and 19th century immigrants ceased speaking German at home, but small populations of speakers are still found in Pennsylvania (approximately 115,000 speakers; Amish, Hutterites, Dunkards and some Mennonites historically spoke Hutterite German and a West Central German variety of German known as Pennsylvania German or Pennsylvania Dutch), Kansas (Mennonites and Volga Germans), North Dakota (Hutterite Germans, Mennonites, Russian Germans, Volga Germans, and Baltic Germans), South Dakota, Montana, Texas (Texas German), Wisconsin, Indiana, Oregon, Oklahoma, and Ohio (72,570). A significant group of German Pietists in Iowa formed the Amana Colonies and continue to practice speaking their heritage language. Early twentieth century immigration was often to St. Louis, Chicago, New York City, Milwaukee, Pittsburgh, and Cincinnati.

The dialects of German which are or were primarily spoken in colonies or communities founded by German-speaking people resemble the dialects of the regions the founders came from. For example, Hutterite German resembles dialects of Carinthia. Texas German is a dialect spoken in the areas of Texas settled by the Adelsverein, such as New Braunfels and Fredericksburg. In the Amana Colonies in the state of Iowa, Amana German is spoken. Plautdietsch is a large minority language spoken in Northern Mexico by the Mennonite communities, and is spoken by more than 200,000 people in Mexico. Pennsylvania German is a West Central German dialect spoken by most of the Amish population of Pennsylvania, Ohio, and Indiana, and resembles Palatinate German dialects.

Hutterite German is an Upper German dialect of the Austro-Bavarian variety of the German language, which is spoken by Hutterite communities in Canada and the United States. Hutterite is spoken in the U.S. states of Washington, Montana, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Minnesota; and in the Canadian provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba. Its speakers belong to some Schmiedleit, Lehrerleit, and Dariusleit Hutterite groups, but there are also speakers among the older generations of Prairieleit (the descendants of those Hutterites who chose not to settle in colonies). Hutterite children who grow up in the colonies learn to speak Hutterite German before learning English, the standard language of the surrounding areas, in school. Many of these children, though, continue with German Grammar School, in addition to public school, throughout a student's elementary education.

Australia

Australia has an estimated population of around 75,600 German speakers. Australians of German ancestry constitute the fourth largest ethnic group in Australia, numbering around 1,026,138. German immigrants played a significant role in settling the states of Queensland and South Australia. Barossa German, a dialect of German, was once common in and around the German-settled Barossa Valley in South Australia. However, the German language was actively suppressed by Australian governments during World War I and World War II, resulting in a sharp decline in the use of German in Australia. German Australians are today overwhelmingly English speaking, with the German language as a home language in heavy decline.

Rest of the world

Minorities exist in the countries of Latin America and the former Soviet Union, as well as Australia, Belgium, Canada, Czechia, Denmark, France, Hungary, Israel, Italy, Namibia, Poland, Romania, South Africa, and the United States. These German minorities, through their ethno-cultural vitality, exhibit an exceptional level of heterogeneity: variations concerning their demographics, their status within the majority community, the support they receive from institutions helping them to support their identity as a minority.

Among them are small groups, such as those in Namibia, and many very large groups, such as the almost 1 million non-evacuated Germans in Russia and Kazakhstan or the near 500,000 Germans in Brazil (see: Riograndenser Hunsrückisch German), groups that have been greatly "folklorised" and almost completely linguistically assimilated, such as most people of German descent in Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, the United States, and others, such as the true linguistic minorities (like the still German-speaking minorities in Argentina, Brazil, and the United States, in Western Siberia or Hungary and Romania); other groups, which are classified as religio-cultural groups rather than ethnic minorities, such as the Eastern-Low German-speaking Mennonites in Belize, Mexico, Paraguay or in the Altay region of Siberia, and the groups who maintain their status thanks to strong identification with their ethnicity and their religious sentiment, such as the groups in Southern Jutland, Denmark or Upper Silesia, Poland.