Peer-to-peer (P2P) computing or networking is a distributed application architecture that partitions tasks or workloads between peers. Peers are equally privileged, equipotent participants in the network. They are said to form a peer-to-peer network of nodes.

Peers make a portion of their resources, such as processing power, disk storage or network bandwidth, directly available to other network participants, without the need for central coordination by servers or stable hosts. Peers are both suppliers and consumers of resources, in contrast to the traditional client–server model in which the consumption and supply of resources are divided.

While P2P systems had previously been used in many application domains, the architecture was popularized by the file sharing system Napster, originally released in 1999. The concept has inspired new structures and philosophies in many areas of human interaction. In such social contexts, peer-to-peer as a meme refers to the egalitarian social networking that has emerged throughout society, enabled by Internet technologies in general.

Historical development

While P2P systems had previously been used in many application domains, the concept was popularized by file sharing systems such as the music-sharing application Napster (originally released in 1999). The peer-to-peer movement allowed millions of Internet users to connect "directly, forming groups and collaborating to become user-created search engines, virtual supercomputers, and filesystems." The basic concept of peer-to-peer computing was envisioned in earlier software systems and networking discussions, reaching back to principles stated in the first Request for Comments, RFC 1.

Tim Berners-Lee's vision for the World Wide Web was close to a P2P network in that it assumed each user of the web would be an active editor and contributor, creating and linking content to form an interlinked "web" of links. The early Internet was more open than the present day, where two machines connected to the Internet could send packets to each other without firewalls and other security measures. This contrasts to the broadcasting-like structure of the web as it has developed over the years. As a precursor to the Internet, ARPANET was a successful client-server network where "every participating node could request and serve content." However, ARPANET was not self-organized, and it lacked the ability to "provide any means for context or content-based routing beyond 'simple' address-based routing."

Therefore, Usenet, a distributed messaging system that is often described as an early peer-to-peer architecture, was established. It was developed in 1979 as a system that enforces a decentralized model of control. The basic model is a client–server model from the user or client perspective that offers a self-organizing approach to newsgroup servers. However, news servers communicate with one another as peers to propagate Usenet news articles over the entire group of network servers. The same consideration applies to SMTP email in the sense that the core email-relaying network of mail transfer agents has a peer-to-peer character, while the periphery of Email clients and their direct connections is strictly a client-server relationship.

In May 1999, with millions more people on the Internet, Shawn Fanning introduced the music and file-sharing application called Napster. Napster was the beginning of peer-to-peer networks, as we know them today, where "participating users establish a virtual network, entirely independent from the physical network, without having to obey any administrative authorities or restrictions."

Architecture

A peer-to-peer network is designed around the notion of equal peer nodes simultaneously functioning as both "clients" and "servers" to the other nodes on the network. This model of network arrangement differs from the client–server model where communication is usually to and from a central server. A typical example of a file transfer that uses the client-server model is the File Transfer Protocol (FTP) service in which the client and server programs are distinct: the clients initiate the transfer, and the servers satisfy these requests.

Routing and resource discovery

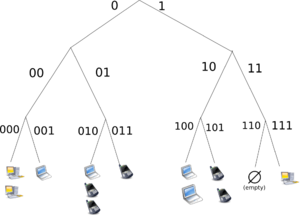

Peer-to-peer networks generally implement some form of virtual overlay network on top of the physical network topology, where the nodes in the overlay form a subset of the nodes in the physical network. Data is still exchanged directly over the underlying TCP/IP network, but at the application layer peers are able to communicate with each other directly, via the logical overlay links (each of which corresponds to a path through the underlying physical network). Overlays are used for indexing and peer discovery, and make the P2P system independent from the physical network topology. Based on how the nodes are linked to each other within the overlay network, and how resources are indexed and located, we can classify networks as unstructured or structured (or as a hybrid between the two).

Unstructured networks

Unstructured peer-to-peer networks do not impose a particular structure on the overlay network by design, but rather are formed by nodes that randomly form connections to each other. (Gnutella, Gossip, and Kazaa are examples of unstructured P2P protocols).

Because there is no structure globally imposed upon them, unstructured networks are easy to build and allow for localized optimizations to different regions of the overlay. Also, because the role of all peers in the network is the same, unstructured networks are highly robust in the face of high rates of "churn"—that is, when large numbers of peers are frequently joining and leaving the network.

However, the primary limitations of unstructured networks also arise from this lack of structure. In particular, when a peer wants to find a desired piece of data in the network, the search query must be flooded through the network to find as many peers as possible that share the data. Flooding causes a very high amount of signaling traffic in the network, uses more CPU/memory (by requiring every peer to process all search queries), and does not ensure that search queries will always be resolved. Furthermore, since there is no correlation between a peer and the content managed by it, there is no guarantee that flooding will find a peer that has the desired data. Popular content is likely to be available at several peers and any peer searching for it is likely to find the same thing. But if a peer is looking for rare data shared by only a few other peers, then it is highly unlikely that search will be successful.

Structured networks

In structured peer-to-peer networks the overlay is organized into a specific topology, and the protocol ensures that any node can efficiently search the network for a file/resource, even if the resource is extremely rare.

The most common type of structured P2P networks implement a distributed hash table (DHT), in which a variant of consistent hashing is used to assign ownership of each file to a particular peer. This enables peers to search for resources on the network using a hash table: that is, (key, value) pairs are stored in the DHT, and any participating node can efficiently retrieve the value associated with a given key.

However, in order to route traffic efficiently through the network, nodes in a structured overlay must maintain lists of neighbors that satisfy specific criteria. This makes them less robust in networks with a high rate of churn (i.e. with large numbers of nodes frequently joining and leaving the network). More recent evaluation of P2P resource discovery solutions under real workloads have pointed out several issues in DHT-based solutions such as high cost of advertising/discovering resources and static and dynamic load imbalance.

Notable distributed networks that use DHTs include Tixati, an alternative to BitTorrent's distributed tracker, the Kad network, the Storm botnet, and the YaCy. Some prominent research projects include the Chord project, Kademlia, PAST storage utility, P-Grid, a self-organized and emerging overlay network, and CoopNet content distribution system. DHT-based networks have also been widely utilized for accomplishing efficient resource discovery for grid computing systems, as it aids in resource management and scheduling of applications.

Hybrid models

Hybrid models are a combination of peer-to-peer and client–server models. A common hybrid model is to have a central server that helps peers find each other. Spotify was an example of a hybrid model [until 2014]. There are a variety of hybrid models, all of which make trade-offs between the centralized functionality provided by a structured server/client network and the node equality afforded by the pure peer-to-peer unstructured networks. Currently, hybrid models have better performance than either pure unstructured networks or pure structured networks because certain functions, such as searching, do require a centralized functionality but benefit from the decentralized aggregation of nodes provided by unstructured networks.

CoopNet content distribution system

CoopNet (Cooperative Networking) was a proposed system for off-loading serving to peers who have recently downloaded content, proposed by computer scientists Venkata N. Padmanabhan and Kunwadee Sripanidkulchai, working at Microsoft Research and Carnegie Mellon University. When a server experiences an increase in load it redirects incoming peers to other peers who have agreed to mirror the content, thus off-loading balance from the server. All of the information is retained at the server. This system makes use of the fact that the bottle-neck is most likely in the outgoing bandwidth than the CPU, hence its server-centric design. It assigns peers to other peers who are 'close in IP' to its neighbors [same prefix range] in an attempt to use locality. If multiple peers are found with the same file it designates that the node choose the fastest of its neighbors. Streaming media is transmitted by having clients cache the previous stream, and then transmit it piece-wise to new nodes.

Security and trust

Peer-to-peer systems pose unique challenges from a computer security perspective.

Like any other form of software, P2P applications can contain vulnerabilities. What makes this particularly dangerous for P2P software, however, is that peer-to-peer applications act as servers as well as clients, meaning that they can be more vulnerable to remote exploits.

Routing attacks

Since each node plays a role in routing traffic through the network, malicious users can perform a variety of "routing attacks", or denial of service attacks. Examples of common routing attacks include "incorrect lookup routing" whereby malicious nodes deliberately forward requests incorrectly or return false results, "incorrect routing updates" where malicious nodes corrupt the routing tables of neighboring nodes by sending them false information, and "incorrect routing network partition" where when new nodes are joining they bootstrap via a malicious node, which places the new node in a partition of the network that is populated by other malicious nodes.

Corrupted data and malware

The prevalence of malware varies between different peer-to-peer protocols. Studies analyzing the spread of malware on P2P networks found, for example, that 63% of the answered download requests on the gnutella network contained some form of malware, whereas only 3% of the content on OpenFT contained malware. In both cases, the top three most common types of malware accounted for the large majority of cases (99% in gnutella, and 65% in OpenFT). Another study analyzing traffic on the Kazaa network found that 15% of the 500,000 file sample taken were infected by one or more of the 365 different computer viruses that were tested for.

Corrupted data can also be distributed on P2P networks by modifying files that are already being shared on the network. For example, on the FastTrack network, the RIAA managed to introduce faked chunks into downloads and downloaded files (mostly MP3 files). Files infected with the RIAA virus were unusable afterwards and contained malicious code. The RIAA is also known to have uploaded fake music and movies to P2P networks in order to deter illegal file sharing. Consequently, the P2P networks of today have seen an enormous increase of their security and file verification mechanisms. Modern hashing, chunk verification and different encryption methods have made most networks resistant to almost any type of attack, even when major parts of the respective network have been replaced by faked or nonfunctional hosts.

Resilient and scalable computer networks

The decentralized nature of P2P networks increases robustness because it removes the single point of failure that can be inherent in a client–server based system. As nodes arrive and demand on the system increases, the total capacity of the system also increases, and the likelihood of failure decreases. If one peer on the network fails to function properly, the whole network is not compromised or damaged. In contrast, in a typical client–server architecture, clients share only their demands with the system, but not their resources. In this case, as more clients join the system, fewer resources are available to serve each client, and if the central server fails, the entire network is taken down.

Distributed storage and search

There are both advantages and disadvantages in P2P networks related to the topic of data backup, recovery, and availability. In a centralized network, the system administrators are the only forces controlling the availability of files being shared. If the administrators decide to no longer distribute a file, they simply have to remove it from their servers, and it will no longer be available to users. Along with leaving the users powerless in deciding what is distributed throughout the community, this makes the entire system vulnerable to threats and requests from the government and other large forces. For example, YouTube has been pressured by the RIAA, MPAA, and entertainment industry to filter out copyrighted content. Although server-client networks are able to monitor and manage content availability, they can have more stability in the availability of the content they choose to host. A client should not have trouble accessing obscure content that is being shared on a stable centralized network. P2P networks, however, are more unreliable in sharing unpopular files because sharing files in a P2P network requires that at least one node in the network has the requested data, and that node must be able to connect to the node requesting the data. This requirement is occasionally hard to meet because users may delete or stop sharing data at any point.

In this sense, the community of users in a P2P network is completely responsible for deciding what content is available. Unpopular files will eventually disappear and become unavailable as more people stop sharing them. Popular files, however, will be highly and easily distributed. Popular files on a P2P network actually have more stability and availability than files on central networks. In a centralized network, a simple loss of connection between the server and clients is enough to cause a failure, but in P2P networks, the connections between every node must be lost in order to cause a data sharing failure. In a centralized system, the administrators are responsible for all data recovery and backups, while in P2P systems, each node requires its own backup system. Because of the lack of central authority in P2P networks, forces such as the recording industry, RIAA, MPAA, and the government are unable to delete or stop the sharing of content on P2P systems.

Applications

Content delivery

In P2P networks, clients both provide and use resources. This means that unlike client–server systems, the content-serving capacity of peer-to-peer networks can actually increase as more users begin to access the content (especially with protocols such as Bittorrent that require users to share, refer a performance measurement study). This property is one of the major advantages of using P2P networks because it makes the setup and running costs very small for the original content distributor.

File-sharing networks

Many peer-to-peer file sharing networks, such as Gnutella, G2, and the eDonkey network popularized peer-to-peer technologies.

- Peer-to-peer content delivery networks.

- Peer-to-peer content services, e.g. caches for improved performance such as Correli Caches

- Software publication and distribution (Linux distribution, several games); via file sharing networks.

Copyright infringements

Peer-to-peer networking involves data transfer from one user to another without using an intermediate server. Companies developing P2P applications have been involved in numerous legal cases, primarily in the United States, over conflicts with copyright law. Two major cases are Grokster vs RIAA and MGM Studios, Inc. v. Grokster, Ltd.. In the last case, the Court unanimously held that defendant peer-to-peer file sharing companies Grokster and Streamcast could be sued for inducing copyright infringement.

Multimedia

- The P2PTV and PDTP protocols.

- Some proprietary multimedia applications use a peer-to-peer network along with streaming servers to stream audio and video to their clients.

- Peercasting for multicasting streams.

- Pennsylvania State University, MIT and Simon Fraser University are carrying on a project called LionShare designed for facilitating file sharing among educational institutions globally.

- Osiris is a program that allows its users to create anonymous and autonomous web portals distributed via P2P network.

Other P2P applications

- Bitcoin and additional such as Ether, Nxt and Peercoin are peer-to-peer-based digital cryptocurrencies.

- Dat, a distributed version-controlled publishing platform.

- Filecoin is an open source, public, cryptocurrency and digital payment system intended to be a blockchain-based cooperative digital storage and data retrieval method.

- I2P, an overlay network used to browse the Internet anonymously.

- Unlike the related I2P, the Tor network is not itself peer-to-peer; however, it can enable peer-to-peer applications to be built on top of it via onion services.

- The InterPlanetary File System (IPFS) is a protocol and network designed to create a content-addressable, peer-to-peer method of storing and sharing hypermedia distribution protocol. Nodes in the IPFS network form a distributed file system.

- Jami, a peer-to-peer chat and SIP app.

- JXTA, a peer-to-peer protocol designed for the Java platform.

- Netsukuku, a Wireless community network designed to be independent from the Internet.

- Open Garden, connection sharing application that shares Internet access with other devices using Wi-Fi or Bluetooth.

- Resilio Sync, a directory-syncing app.

- Research like the Chord project, the PAST storage utility, the P-Grid, and the CoopNet content distribution system.

- Syncthing, a directory-syncing app.

- Tradepal and M-commerce applications that power real-time marketplaces.

- The U.S. Department of Defense is conducting research on P2P networks as part of its modern network warfare strategy. In May, 2003, Anthony Tether, then director of DARPA, testified that the United States military uses P2P networks.

- WebTorrent is a P2P streaming torrent client in JavaScript for use in web browsers, as well as in the WebTorrent Desktop stand alone version that bridges WebTorrent and BitTorrent serverless networks.

- Microsoft in Windows 10 uses a proprietary peer to peer technology called "Delivery Optimization" to deploy operating system updates using end-users PCs either on the local network or other PCs. According to Microsoft's Channel 9 it led to a 30%-50% reduction in Internet bandwidth usage.

- Artisoft's LANtastic was built as a peer-to-peer operating system. Machines can be both servers and workstations at the same time.

- Hotline Communications Hotline Client was built as decentralized servers with tracker software dedicated to any type of files and still operates today.

Social implications

Incentivizing resource sharing and cooperation

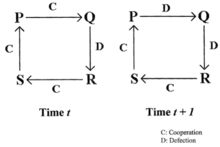

Cooperation among a community of participants is key to the continued success of P2P systems aimed at casual human users; these reach their full potential only when large numbers of nodes contribute resources. But in current practice, P2P networks often contain large numbers of users who utilize resources shared by other nodes, but who do not share anything themselves (often referred to as the "freeloader problem"). Freeloading can have a profound impact on the network and in some cases can cause the community to collapse. In these types of networks "users have natural disincentives to cooperate because cooperation consumes their own resources and may degrade their own performance." Studying the social attributes of P2P networks is challenging due to large populations of turnover, asymmetry of interest and zero-cost identity. A variety of incentive mechanisms have been implemented to encourage or even force nodes to contribute resources.

Some researchers have explored the benefits of enabling virtual communities to self-organize and introduce incentives for resource sharing and cooperation, arguing that the social aspect missing from today's P2P systems should be seen both as a goal and a means for self-organized virtual communities to be built and fostered. Ongoing research efforts for designing effective incentive mechanisms in P2P systems, based on principles from game theory, are beginning to take on a more psychological and information-processing direction.

Privacy and anonymity

Some peer-to-peer networks (e.g. Freenet) place a heavy emphasis on privacy and anonymity—that is, ensuring that the contents of communications are hidden from eavesdroppers, and that the identities/locations of the participants are concealed. Public key cryptography can be used to provide encryption, data validation, authorization, and authentication for data/messages. Onion routing and other mix network protocols (e.g. Tarzan) can be used to provide anonymity.

Perpetrators of live streaming sexual abuse and other cybercrimes have used peer-to-peer platforms to carry out activities with anonymity.

Political implications

Intellectual property law and illegal sharing

Although peer-to-peer networks can be used for legitimate purposes, rights holders have targeted peer-to-peer over the involvement with sharing copyrighted material. Peer-to-peer networking involves data transfer from one user to another without using an intermediate server. Companies developing P2P applications have been involved in numerous legal cases, primarily in the United States, primarily over issues surrounding copyright law. Two major cases are Grokster vs RIAA and MGM Studios, Inc. v. Grokster, Ltd. In both of the cases the file sharing technology was ruled to be legal as long as the developers had no ability to prevent the sharing of the copyrighted material. To establish criminal liability for the copyright infringement on peer-to-peer systems, the government must prove that the defendant infringed a copyright willingly for the purpose of personal financial gain or commercial advantage. Fair use exceptions allow limited use of copyrighted material to be downloaded without acquiring permission from the rights holders. These documents are usually news reporting or under the lines of research and scholarly work. Controversies have developed over the concern of illegitimate use of peer-to-peer networks regarding public safety and national security. When a file is downloaded through a peer-to-peer network, it is impossible to know who created the file or what users are connected to the network at a given time. Trustworthiness of sources is a potential security threat that can be seen with peer-to-peer systems.

A study ordered by the European Union found that illegal downloading may lead to an increase in overall video game sales because newer games charge for extra features or levels. The paper concluded that piracy had a negative financial impact on movies, music, and literature. The study relied on self-reported data about game purchases and use of illegal download sites. Pains were taken to remove effects of false and misremembered responses.

Network neutrality

Peer-to-peer applications present one of the core issues in the network neutrality controversy. Internet service providers (ISPs) have been known to throttle P2P file-sharing traffic due to its high-bandwidth usage. Compared to Web browsing, e-mail or many other uses of the internet, where data is only transferred in short intervals and relative small quantities, P2P file-sharing often consists of relatively heavy bandwidth usage due to ongoing file transfers and swarm/network coordination packets. In October 2007, Comcast, one of the largest broadband Internet providers in the United States, started blocking P2P applications such as BitTorrent. Their rationale was that P2P is mostly used to share illegal content, and their infrastructure is not designed for continuous, high-bandwidth traffic. Critics point out that P2P networking has legitimate legal uses, and that this is another way that large providers are trying to control use and content on the Internet, and direct people towards a client–server-based application architecture. The client–server model provides financial barriers-to-entry to small publishers and individuals, and can be less efficient for sharing large files. As a reaction to this bandwidth throttling, several P2P applications started implementing protocol obfuscation, such as the BitTorrent protocol encryption. Techniques for achieving "protocol obfuscation" involves removing otherwise easily identifiable properties of protocols, such as deterministic byte sequences and packet sizes, by making the data look as if it were random. The ISP's solution to the high bandwidth is P2P caching, where an ISP stores the part of files most accessed by P2P clients in order to save access to the Internet.

Current research

Researchers have used computer simulations to aid in understanding and evaluating the complex behaviors of individuals within the network. "Networking research often relies on simulation in order to test and evaluate new ideas. An important requirement of this process is that results must be reproducible so that other researchers can replicate, validate, and extend existing work." If the research cannot be reproduced, then the opportunity for further research is hindered. "Even though new simulators continue to be released, the research community tends towards only a handful of open-source simulators. The demand for features in simulators, as shown by our criteria and survey, is high. Therefore, the community should work together to get these features in open-source software. This would reduce the need for custom simulators, and hence increase repeatability and reputability of experiments."

Besides all the above stated facts, there has also been work done on ns-2 open source network simulators. One research issue related to free rider detection and punishment has been explored using ns-2 simulator here.