The multiverse is the hypothetical set of all universes. Together, these universes are presumed to comprise everything that exists: the entirety of space, time, matter, energy, information, and the physical laws and constants that describe them. The different universes within the multiverse are called "parallel universes", "flat universes", "other universes", "alternate universes", "multiple universes", "plane universes", "parent and child universes", "many universes", or "many worlds". One common assumption is that the multiverse is a "patchwork quilt of separate universes all bound by the same laws of physics."

The concept of multiple universes, or a multiverse, has been discussed throughout history. It has evolved and has been debated in various fields, including cosmology, physics, and philosophy. Some physicists have argued that the multiverse is a philosophical notion rather than a scientific hypothesis, as it cannot be empirically falsified. In recent years, there have been proponents and skeptics of multiverse theories within the physics community. Although some scientists have analyzed data in search of evidence for other universes, no statistically significant evidence has been found. Critics argue that the multiverse concept lacks testability and falsifiability, which are essential for scientific inquiry, and that it raises unresolved metaphysical issues.

Max Tegmark and Brian Greene have proposed different classification schemes for multiverses and universes. Tegmark's four-level classification consists of Level I: an extension of our universe, Level II: universes with different physical constants, Level III: many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics, and Level IV: ultimate ensemble. Brian Greene's nine types of multiverses include quilted, inflationary, brane, cyclic, landscape, quantum, holographic, simulated, and ultimate. The ideas explore various dimensions of space, physical laws, and mathematical structures to explain the existence and interactions of multiple universes. Some other multiverse concepts include twin-world models, cyclic theories, M-theory, and black-hole cosmology.

The anthropic principle suggests that the existence of a multitude of universes, each with different physical laws, could explain the asserted appearance of fine-tuning of our own universe for conscious life. The weak anthropic principle posits that we exist in one of the few universes that support life. Debates around Occam's razor and the simplicity of the multiverse versus a single universe arise, with proponents like Max Tegmark arguing that the multiverse is simpler and more elegant. The many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics and modal realism, the belief that all possible worlds exist and are as real as our world, are also subjects of debate in the context of the anthropic principle.

History of the concept

According to some, the idea of infinite worlds was first suggested by the pre-Socratic Greek philosopher Anaximander in the sixth century BCE. However, there is debate as to whether he believed in multiple worlds, and if he did, whether those worlds were co-existent or successive.

The first figures to whom historians can definitively attribute the concept of innumerable worlds are the Ancient Greek Atomists, beginning with Leucippus and Democritus in the 5th century BCE, followed by Epicurus (341–270 BCE) and the Roman Epicurean Lucretius (1st century BCE). In the third century BCE, the philosopher Chrysippus suggested that the world eternally expired and regenerated, effectively suggesting the existence of multiple universes across time. The concept of multiple universes became more defined in the Middle Ages. In the Renaissance, Giordano Bruno (1548-1600) expressed the concept of infinite worlds.

The American philosopher and psychologist William James used the term "multiverse" in 1895, but in a different context.

The concept first appeared in the modern scientific context in the course of the debate between Boltzmann and Zermelo in 1895.

In Dublin in 1952, Erwin Schrödinger gave a lecture in which he jocularly warned his audience that what he was about to say might "seem lunatic". He said that when his equations seemed to describe several different histories, these were "not alternatives, but all really happen simultaneously". This sort of duality is called "superposition".

Search for evidence

In the 1990s, after recent works of fiction about the concept gained popularity, scientific discussions about the multiverse and journal articles about it gained prominence.

Around 2010, scientists such as Stephen M. Feeney analyzed Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe (WMAP) data and claimed to find evidence suggesting that this universe collided with other (parallel) universes in the distant past. However, a more thorough analysis of data from the WMAP and from the Planck satellite, which has a resolution three times higher than WMAP, did not reveal any statistically significant evidence of such a bubble universe collision. In addition, there was no evidence of any gravitational pull of other universes on ours.

In 2015, an astrophysicist may have found evidence of alternate or parallel universes by looking back in time to a time immediately after the Big Bang, although it is still a matter of debate among physicists. Dr. Ranga-Ram Chary, after analyzing the cosmic radiation spectrum, found a signal 4,500 times brighter than it should have been, based on the number of protons and electrons scientists believe existed in the very early universe. This signal—an emission line that arose from the formation of atoms during the era of recombination—is more consistent with a universe whose ratio of matter particles to photons is about 65 times greater than our own. There is a 30% chance that this signal is noise, and not really a signal at all; however, it is also possible that it exists because a parallel universe dumped some of its matter particles into our universe. If additional protons and electrons had been added to our universe during recombination, more atoms would have formed, more photons would have been emitted during their formation, and the signature line that arose from all of these emissions would be greatly enhanced. Chary said:

Many other regions beyond our observable universe would exist with each such region governed by a different set of physical parameters than the ones we have measured for our universe.

— Ranga-Ram Chary, USA Today

Chary also noted:

Unusual claims like evidence for alternate universes require a very high burden of proof.

— Ranga-Ram Chary, "Universe Today"

The signature that Chary has isolated may be a consequence of incoming light from distant galaxies, or even from clouds of dust surrounding our own galaxy.

Proponents and skeptics

Modern proponents of one or more of the multiverse hypotheses include Lee Smolin, Don Page, Brian Greene, Max Tegmark, Alan Guth, Andrei Linde, Michio Kaku, David Deutsch, Leonard Susskind, Alexander Vilenkin, Yasunori Nomura, Raj Pathria, Laura Mersini-Houghton, Neil deGrasse Tyson, Sean Carroll and Stephen Hawking.

Scientists who are generally skeptical of the concept of a multiverse or popular multiverse hypotheses include Sabine Hossenfelder, David Gross, Paul Steinhardt, Anna Ijjas, Abraham Loeb, David Spergel, Neil Turok, Viatcheslav Mukhanov, Michael S. Turner, Roger Penrose, George Ellis, Joe Silk, Carlo Rovelli, Adam Frank, Marcelo Gleiser, Jim Baggott and Paul Davies.

Arguments against multiverse hypotheses

In his 2003 New York Times opinion piece, "A Brief History of the Multiverse", author and cosmologist Paul Davies offered a variety of arguments that multiverse hypotheses are non-scientific:

For a start, how is the existence of the other universes to be tested? To be sure, all cosmologists accept that there are some regions of the universe that lie beyond the reach of our telescopes, but somewhere on the slippery slope between that and the idea that there is an infinite number of universes, credibility reaches a limit. As one slips down that slope, more and more must be accepted on faith, and less and less is open to scientific verification. Extreme multiverse explanations are therefore reminiscent of theological discussions. Indeed, invoking an infinity of unseen universes to explain the unusual features of the one we do see is just as ad hoc as invoking an unseen Creator. The multiverse theory may be dressed up in scientific language, but in essence, it requires the same leap of faith.

— Paul Davies, "A Brief History of the Multiverse", The New York Times

George Ellis, writing in August 2011, provided a criticism of the multiverse, and pointed out that it is not a traditional scientific theory. He accepts that the multiverse is thought to exist far beyond the cosmological horizon. He emphasized that it is theorized to be so far away that it is unlikely any evidence will ever be found. Ellis also explained that some theorists do not believe the lack of empirical testability and falsifiability is a major concern, but he is opposed to that line of thinking:

Many physicists who talk about the multiverse, especially advocates of the string landscape, do not care much about parallel universes per se. For them, objections to the multiverse as a concept are unimportant. Their theories live or die based on internal consistency and, one hopes, eventual laboratory testing.

Ellis says that scientists have proposed the idea of the multiverse as a way of explaining the nature of existence. He points out that it ultimately leaves those questions unresolved because it is a metaphysical issue that cannot be resolved by empirical science. He argues that observational testing is at the core of science and should not be abandoned:

As skeptical as I am, I think the contemplation of the multiverse is an excellent opportunity to reflect on the nature of science and on the ultimate nature of existence: why we are here. ... In looking at this concept, we need an open mind, though not too open. It is a delicate path to tread. Parallel universes may or may not exist; the case is unproved. We are going to have to live with that uncertainty. Nothing is wrong with scientifically based philosophical speculation, which is what multiverse proposals are. But we should name it for what it is.

— George Ellis, "Does the Multiverse Really Exist?", Scientific American

Philosopher Philip Goff argues that the inference of a multiverse to explain the apparent fine-tuning of the universe is an example of Inverse Gambler's Fallacy.

Stoeger, Ellis, and Kircher note that in a true multiverse theory, "the universes are then completely disjoint and nothing that happens in any one of them is causally linked to what happens in any other one. This lack of any causal connection in such multiverses really places them beyond any scientific support".

In May 2020, astrophysicist Ethan Siegel expressed criticism in a Forbes blog post that parallel universes would have to remain a science fiction dream for the time being, based on the scientific evidence available to us.

Scientific American contributor John Horgan also argues against the idea of a multiverse, claiming that they are "bad for science."

Types

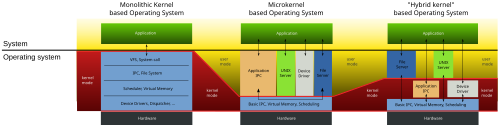

Max Tegmark and Brian Greene have devised classification schemes for the various theoretical types of multiverses and universes that they might comprise.

Max Tegmark's four levels

Cosmologist Max Tegmark has provided a taxonomy of universes beyond the familiar observable universe. The four levels of Tegmark's classification are arranged such that subsequent levels can be understood to encompass and expand upon previous levels. They are briefly described below.

Level I: An extension of our universe

A prediction of cosmic inflation is the existence of an infinite ergodic universe, which, being infinite, must contain Hubble volumes realizing all initial conditions.

Accordingly, an infinite universe will contain an infinite number of Hubble volumes, all having the same physical laws and physical constants. In regard to configurations such as the distribution of matter, almost all will differ from our Hubble volume. However, because there are infinitely many, far beyond the cosmological horizon, there will eventually be Hubble volumes with similar, and even identical, configurations. Tegmark estimates that an identical volume to ours should be about 1010115 meters away from us.

Given infinite space, there would be an infinite number of Hubble volumes identical to ours in the universe. This follows directly from the cosmological principle, wherein it is assumed that our Hubble volume is not special or unique.

Level II: Universes with different physical constants

In the eternal inflation theory, which is a variant of the cosmic inflation theory, the multiverse or space as a whole is stretching and will continue doing so forever, but some regions of space stop stretching and form distinct bubbles (like gas pockets in a loaf of rising bread). Such bubbles are embryonic level I multiverses.

Different bubbles may experience different spontaneous symmetry breaking, which results in different properties, such as different physical constants.

Level II also includes John Archibald Wheeler's oscillatory universe theory and Lee Smolin's fecund universes theory.

Level III: Many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics

Hugh Everett III's many-worlds interpretation (MWI) is one of several mainstream interpretations of quantum mechanics.

In brief, one aspect of quantum mechanics is that certain observations cannot be predicted absolutely. Instead, there is a range of possible observations, each with a different probability. According to the MWI, each of these possible observations corresponds to a different "world" within the Universal wavefunction, with each world as real as ours. Suppose a six-sided die is thrown and that the result of the throw corresponds to observable quantum mechanics. All six possible ways the die can fall correspond to six different worlds. In the case of the Schrödinger's cat thought experiment, both outcomes would be "real" in at least one "world".

Tegmark argues that a Level III multiverse does not contain more possibilities in the Hubble volume than a Level I or Level II multiverse. In effect, all the different worlds created by "splits" in a Level III multiverse with the same physical constants can be found in some Hubble volume in a Level I multiverse. Tegmark writes that, "The only difference between Level I and Level III is where your doppelgängers reside. In Level I they live elsewhere in good old three-dimensional space. In Level III they live on another quantum branch in infinite-dimensional Hilbert space."

Similarly, all Level II bubble universes with different physical constants can, in effect, be found as "worlds" created by "splits" at the moment of spontaneous symmetry breaking in a Level III multiverse. According to Yasunori Nomura, Raphael Bousso, and Leonard Susskind, this is because global spacetime appearing in the (eternally) inflating multiverse is a redundant concept. This implies that the multiverses of Levels I, II, and III are, in fact, the same thing. This hypothesis is referred to as "Multiverse = Quantum Many Worlds". According to Yasunori Nomura, this quantum multiverse is static, and time is a simple illusion.

Another version of the many-worlds idea is H. Dieter Zeh's many-minds interpretation.

Level IV: Ultimate ensemble

The ultimate mathematical universe hypothesis is Tegmark's own hypothesis.

This level considers all universes to be equally real which can be described by different mathematical structures.

Tegmark writes:

Abstract mathematics is so general that any Theory Of Everything (TOE) which is definable in purely formal terms (independent of vague human terminology) is also a mathematical structure. For instance, a TOE involving a set of different types of entities (denoted by words, say) and relations between them (denoted by additional words) is nothing but what mathematicians call a set-theoretical model, and one can generally find a formal system that it is a model of.

He argues that this "implies that any conceivable parallel universe theory can be described at Level IV" and "subsumes all other ensembles, therefore brings closure to the hierarchy of multiverses, and there cannot be, say, a Level V."

Jürgen Schmidhuber, however, says that the set of mathematical structures is not even well-defined and that it admits only universe representations describable by constructive mathematics—that is, computer programs.

Schmidhuber explicitly includes universe representations describable by non-halting programs whose output bits converge after a finite time, although the convergence time itself may not be predictable by a halting program, due to the undecidability of the halting problem. He also explicitly discusses the more restricted ensemble of quickly computable universes.

Brian Greene's nine types

The American theoretical physicist and string theorist Brian Greene discussed nine types of multiverses:

- Quilted

- The quilted multiverse works only in an infinite universe. With an infinite amount of space, every possible event will occur an infinite number of times. However, the speed of light prevents us from being aware of these other identical areas.

- Inflationary

- The inflationary multiverse is composed of various pockets in which inflation fields collapse and form new universes.

- Brane

- The brane multiverse version postulates that our entire universe exists on a membrane (brane) which floats in a higher dimension or "bulk". In this bulk, there are other membranes with their own universes. These universes can interact with one another, and when they collide, the violence and energy produced is more than enough to give rise to a Big Bang. The branes float or drift near each other in the bulk, and every few trillion years, attracted by gravity or some other force we do not understand, collide and bang into each other. This repeated contact gives rise to multiple or "cyclic" Big Bangs. This particular hypothesis falls under the string theory umbrella as it requires extra spatial dimensions.

- Cyclic

- The cyclic multiverse has multiple branes that have collided, causing Big Bangs. The universes bounce back and pass through time until they are pulled back together and again collide, destroying the old contents and creating them anew.

- Landscape

- The landscape multiverse relies on string theory's Calabi–Yau spaces. Quantum fluctuations drop the shapes to a lower energy level, creating a pocket with a set of laws different from that of the surrounding space.

- Quantum

- The quantum multiverse creates a new universe when a diversion in events occurs, as in the real-worlds variant of the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics.

- Holographic

- The holographic multiverse is derived from the theory that the surface area of a space can encode the contents of the volume of the region.

- Simulated

- The simulated multiverse exists on complex computer systems that simulate entire universes. A related hypothesis, as put forward as a possibility by astronomer Avi Loeb, is that universes may be creatable in laboratories of advanced technological civilizations who have a theory of everything. Other related hypotheses include brain in a vat-type scenarios where the perceived universe is either simulated in a low-resource way or not perceived directly by the virtual/simulated inhabitant species.

- Ultimate

- The ultimate multiverse contains every mathematically possible universe under different laws of physics.

Twin-world models

There are models of two related universes that e.g. attempt to explain the baryon asymmetry – why there was more matter than antimatter at the beginning – with a mirror anti-universe. One two-universe cosmological model could explain the Hubble constant (H0) tension via interactions between the two worlds. The "mirror world" would contain copies of all existing fundamental particles. Another twin/pair-world or "bi-world" cosmology is shown to theoretically be able to solve the cosmological constant (Λ) problem, closely related to dark energy: two interacting worlds with a large Λ each could result in a small shared effective Λ.

Cyclic theories

In several theories, there is a series of, in some cases infinite, self-sustaining cycles – typically a series of Big Crunches (or Big Bounces). However, the respective universes do not exist at once but are forming or following in a logical order or sequence, with key natural constituents potentially varying between universes (see § Anthropic principle).

M-theory

A multiverse of a somewhat different kind has been envisaged within string theory and its higher-dimensional extension, M-theory.

These theories require the presence of 10 or 11 spacetime dimensions, respectively. The extra six or seven dimensions may either be compactified on a very small scale, or our universe may simply be localized on a dynamical (3+1)-dimensional object, a D3-brane. This opens up the possibility that there are other branes which could support other universes.

Black-hole cosmology

Black-hole cosmology is a cosmological model in which the observable universe is the interior of a black hole existing as one of possibly many universes inside a larger universe. This includes the theory of white holes, which are on the opposite side of space-time.

Anthropic principle

The concept of other universes has been proposed to explain how our own universe appears to be fine-tuned for conscious life as we experience it.

If there were a large (possibly infinite) number of universes, each with possibly different physical laws (or different fundamental physical constants), then some of these universes (even if very few) would have the combination of laws and fundamental parameters that are suitable for the development of matter, astronomical structures, elemental diversity, stars, and planets that can exist long enough for life to emerge and evolve.

The weak anthropic principle could then be applied to conclude that we (as conscious beings) would only exist in one of those few universes that happened to be finely tuned, permitting the existence of life with developed consciousness. Thus, while the probability might be extremely small that any particular universe would have the requisite conditions for life (as we understand life), those conditions do not require intelligent design as an explanation for the conditions in the Universe that promote our existence in it.

An early form of this reasoning is evident in Arthur Schopenhauer's 1844 work "Von der Nichtigkeit und dem Leiden des Lebens", where he argues that our world must be the worst of all possible worlds, because if it were significantly worse in any respect it could not continue to exist.

Occam's razor

Proponents and critics disagree about how to apply Occam's razor. Critics argue that to postulate an almost infinite number of unobservable universes, just to explain our own universe, is contrary to Occam's razor. However, proponents argue that in terms of Kolmogorov complexity the proposed multiverse is simpler than a single idiosyncratic universe.

For example, multiverse proponent Max Tegmark argues:

[A]n entire ensemble is often much simpler than one of its members. This principle can be stated more formally using the notion of algorithmic information content. The algorithmic information content in a number is, roughly speaking, the length of the shortest computer program that will produce that number as output. For example, consider the set of all integers. Which is simpler, the whole set or just one number? Naively, you might think that a single number is simpler, but the entire set can be generated by quite a trivial computer program, whereas a single number can be hugely long. Therefore, the whole set is actually simpler... (Similarly), the higher-level multiverses are simpler. Going from our universe to the Level I multiverse eliminates the need to specify initial conditions, upgrading to Level II eliminates the need to specify physical constants, and the Level IV multiverse eliminates the need to specify anything at all... A common feature of all four multiverse levels is that the simplest and arguably most elegant theory involves parallel universes by default. To deny the existence of those universes, one needs to complicate the theory by adding experimentally unsupported processes and ad hoc postulates: finite space, wave function collapse and ontological asymmetry. Our judgment therefore comes down to which we find more wasteful and inelegant: many worlds or many words. Perhaps we will gradually get used to the weird ways of our cosmos and find its strangeness to be part of its charm.

— Max Tegmark

Possible worlds and real worlds

In any given set of possible universes – e.g. in terms of histories or variables of nature – not all may be ever realized, and some may be realized many times. For example, over infinite time there could, in some potential theories, be infinite universes, but only a small or relatively small real number of universes where humanity could exist and only one where it ever does exist (with a unique history). It has been suggested that a universe that "contains life, in the form it has on Earth, is in a certain sense radically non-ergodic, in that the vast majority of possible organisms will never be realized". On the other hand, some scientists, theories and popular works conceive of a multiverse in which the universes are so similar that humanity exists in many equally real separate universes but with varying histories.

There is a debate about whether the other worlds are real in the many-worlds interpretation (MWI) of quantum mechanics. In Quantum Darwinism one does not need to adopt a MWI in which all of the branches are equally real.