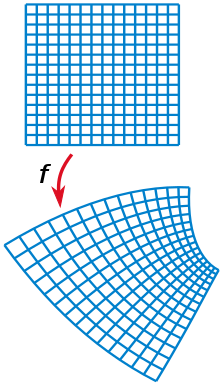

A rectangular grid (top) and its image under a Conformal map f (bottom).

In mathematics, a holomorphic function is a complex-valued function of one or more complex variables that is complex differentiable in a neighborhood of every point in its domain. The existence of a complex derivative in a neighborhood is a very strong condition, for it implies that any holomorphic function is actually infinitely differentiable and equal to its own Taylor series (analytic). Holomorphic functions are the central objects of study in complex analysis.

Though the term analytic function is often used interchangeably with "holomorphic function", the word "analytic" is defined in a broader sense to denote any function (real, complex, or of more general type) that can be written as a convergent power series in a neighborhood of each point in its domain. The fact that all holomorphic functions are complex analytic functions, and vice versa, is a major theorem in complex analysis.

Holomorphic functions are also sometimes referred to as regular functions. A holomorphic function whose domain is the whole complex plane is called an entire function. The phrase "holomorphic at a point z0" means not just differentiable at z0, but differentiable everywhere within some neighborhood of z0 in the complex plane.

Definition

The function  is not complex-differentiable at zero, because as shown above, the value of

is not complex-differentiable at zero, because as shown above, the value of  varies depending on the direction from which zero is approached. Along the real axis, f equals the function g(z) = z and the limit is 1, while along the imaginary axis, f equals h(z) = −z and the limit is −1. Other directions yield yet other limits.

varies depending on the direction from which zero is approached. Along the real axis, f equals the function g(z) = z and the limit is 1, while along the imaginary axis, f equals h(z) = −z and the limit is −1. Other directions yield yet other limits.

is not complex-differentiable at zero, because as shown above, the value of

is not complex-differentiable at zero, because as shown above, the value of  varies depending on the direction from which zero is approached. Along the real axis, f equals the function g(z) = z and the limit is 1, while along the imaginary axis, f equals h(z) = −z and the limit is −1. Other directions yield yet other limits.

varies depending on the direction from which zero is approached. Along the real axis, f equals the function g(z) = z and the limit is 1, while along the imaginary axis, f equals h(z) = −z and the limit is −1. Other directions yield yet other limits.Given a complex-valued function f of a single complex variable, the derivative of f at a point z0 in its domain is defined by the limit

If f is complex differentiable at every point z0 in an open set U, we say that f is holomorphic on U. We say that f is holomorphic at the point z0 if it is holomorphic on some neighborhood of z0. We say that f is holomorphic on some non-open set A if it is holomorphic in an open set containing A. As a pathological non-example, the function given by f(z) = |z|2 is complex differentiable at exactly one point (z0 = 0), and for this reason, it is not holomorphic at 0 because there is no open set around 0 on which f is complex differentiable.

The relationship between real differentiability and complex differentiability is the following. If a complex function f(x + i y) = u(x, y) + i v(x, y) is holomorphic, then u and v have first partial derivatives with respect to x and y, and satisfy the Cauchy–Riemann equations:

If continuity is not given, the converse is not necessarily true. A simple converse is that if u and v have continuous first partial derivatives and satisfy the Cauchy–Riemann equations, then f is holomorphic. A more satisfying converse, which is much harder to prove, is the Looman–Menchoff theorem: if f is continuous, u and v have first partial derivatives (but not necessarily continuous), and they satisfy the Cauchy–Riemann equations, then f is holomorphic.

Terminology

The word "holomorphic" was introduced by two of Cauchy's students, Briot (1817–1882) and Bouquet (1819–1895), and derives from the Greek ὅλος (holos) meaning "entire", and μορφή (morphē) meaning "form" or "appearance".Today, the term "holomorphic function" is sometimes preferred to "analytic function", as the latter is a more general concept. This is also because an important result in complex analysis is that every holomorphic function is complex analytic, a fact that does not follow obviously from the definitions. The term "analytic" is however also in wide use.

Properties

Because complex differentiation is linear and obeys the product, quotient, and chain rules; the sums, products and compositions of holomorphic functions are holomorphic, and the quotient of two holomorphic functions is holomorphic wherever the denominator is not zero.If one identifies C with R2, then the holomorphic functions coincide with those functions of two real variables with continuous first derivatives which solve the Cauchy–Riemann equations, a set of two partial differential equations.

Every holomorphic function can be separated into its real and imaginary parts, and each of these is a solution of Laplace's equation on R2. In other words, if we express a holomorphic function f(z) as u(x, y) + i v(x, y) both u and v are harmonic functions, where v is the harmonic conjugate of u.

Cauchy's integral theorem implies that the contour integral of every holomorphic function along a loop vanishes:

Cauchy's integral formula states that every function holomorphic inside a disk is completely determined by its values on the disk's boundary. Furthermore: Suppose U is an open subset of C, f : U → C is a holomorphic function and the closed disk D = {z : |z − z0| ≤ r} is completely contained in U. Let γ be the circle forming the boundary of D. Then for every a in the interior of D:

The derivative f′(a) can be written as a contour integral using Cauchy's differentiation formula:

In regions where the first derivative is not zero, holomorphic functions are conformal in the sense that they preserve angles and the shape (but not size) of small figures.

Every holomorphic function is analytic. That is, a holomorphic function f has derivatives of every order at each point a in its domain, and it coincides with its own Taylor series at a in a neighborhood of a. In fact, f coincides with its Taylor series at a in any disk centered at that point and lying within the domain of the function.

From an algebraic point of view, the set of holomorphic functions on an open set is a commutative ring and a complex vector space. Additionally, the set of holomorphic functions in an open set U is an integral domain if and only if the open set U is connected. In fact, it is a locally convex topological vector space, with the seminorms being the suprema on compact subsets.

From a geometric perspective, a function f is holomorphic at z0 if and only if its exterior derivative df in a neighborhood U of z0 is equal to f′(z) dz for some continuous function f′. It follows from

;

Examples

All polynomial functions in z with complex coefficients are holomorphic on C, and so are sine, cosine and the exponential function. (The trigonometric functions are in fact closely related to and can be defined via the exponential function using Euler's formula). The principal branch of the complex logarithm function is holomorphic on the set C ∖ {z ∈ R : z ≤ 0}. The square root function can be defined asAs a consequence of the Cauchy–Riemann equations, a real-valued holomorphic function must be constant. Therefore, the absolute value of z, the argument of z, the real part of z and the imaginary part of z are not holomorphic. Another typical example of a continuous function which is not holomorphic is the complex conjugate z formed by complex conjugation.

Several variables

The definition of a holomorphic function generalizes to several complex variables in a straightforward way. Let D denote an open subset of Cn, and let f : D → C. The function f is analytic at a point p in D if there exists an open neighborhood of p in which f is equal to a convergent power series in n complex variables. Define f to be holomorphic if it is analytic at each point in its domain. Osgood's lemma shows (using the multivariate Cauchy integral formula) that, for a continuous function f, this is equivalent to f being holomorphic in each variable separately (meaning that if any n − 1 coordinates are fixed, then the restriction of f is a holomorphic function of the remaining coordinate). The much deeper Hartogs' theorem proves that the continuity hypothesis is unnecessary: f is holomorphic if and only if it is holomorphic in each variable separately.More generally, a function of several complex variables that is square integrable over every compact subset of its domain is analytic if and only if it satisfies the Cauchy–Riemann equations in the sense of distributions.

Functions of several complex variables are in some basic ways more complicated than functions of a single complex variable. For example, the region of convergence of a power series is not necessarily an open ball; these regions are Reinhardt domains, the simplest example of which is a polydisk. However, they also come with some fundamental restrictions. Unlike functions of a single complex variable, the possible domains on which there are holomorphic functions that cannot be extended to larger domains are highly limited. Such a set is called a domain of holomorphy.