Java applets were small applications written in the Java programming language, or another programming language that compiles to Java bytecode, and delivered to users in the form of Java bytecode. The user launched the Java applet from a web page, and the applet was then executed within a Java virtual machine (JVM) in a process separate from the web browser itself. A Java applet could appear in a frame of the web page, a new application window, Sun's AppletViewer, or a stand-alone tool for testing applets.

Java applets were introduced in the first version of the Java language, which was released in 1995. Beginning in 2013, major web browsers began to phase out support for the underlying technology applets used to run, with applets becoming completely unable to be run by 2015–2017. Java applets were deprecated by Java 9 in 2017.

Java applets were usually written in Java, but other languages such as Jython, JRuby, Pascal, Scala, NetRexx, or Eiffel (via SmartEiffel) could be used as well.

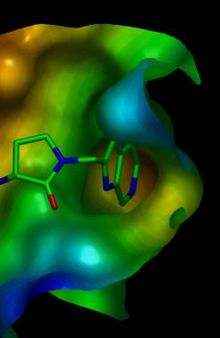

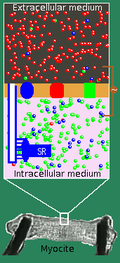

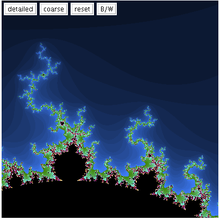

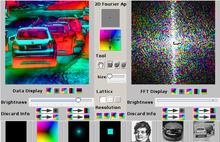

Java applets run at very fast speeds and until 2011, they were many times faster than JavaScript.[citation needed] Unlike JavaScript, Java applets had access to 3D hardware acceleration, making them well-suited for non-trivial, computation-intensive visualizations. As browsers have gained support for hardware-accelerated graphics thanks to the canvas technology (or specifically WebGL in the case of 3D graphics), as well as just-in-time compiled JavaScript, the speed difference has become less noticeable.

Since Java bytecode is cross-platform (or platform independent), Java applets could be executed by clients for many platforms, including Microsoft Windows, FreeBSD, Unix, macOS and Linux. They could not be run on mobile devices, which do not support running standard Oracle JVM bytecode. Android devices can run code written in Java compiled for the Android Runtime.

Overview

The applets are used to provide interactive features to web applications that cannot be provided by HTML alone. They can capture mouse input and also have controls like buttons or check boxes. In response to user actions, an applet can change the provided graphic content. This makes applets well-suited for demonstration, visualization, and teaching. There are online applet collections for studying various subjects, from physics to heart physiology.

An applet can also be a text area only; providing, for instance, a cross-platform command-line interface to some remote system. If needed, an applet can leave the dedicated area and run as a separate window. However, applets have very little control over web page content outside the applet's dedicated area, so they are less useful for improving the site appearance in general, unlike other types of browser extensions (while applets like news tickers or WYSIWYG editors are also known). Applets can also play media in formats that are not natively supported by the browser.

Pages coded in HTML may embed parameters within them that are passed to the applet. Because of this, the same applet may have a different appearance depending on the parameters that were passed.

As applets were available before HTML5, modern CSS and JavaScript interface DOM were standard, they were also widely used for trivial effects such as mouseover and navigation buttons. This approach, which posed major problems for accessibility and misused system resources, is no longer in use and was strongly discouraged even at the time.

Technical information

Most browsers executed Java applets in a sandbox, preventing applets from accessing local data like the file system. The code of the applet was downloaded from a web server, after which the browser either embedded the applet into a web page or opened a new window showing the applet's user interface.

The first implementations involved downloading an applet class by

class. While classes are small files, there are often many of them, so

applets got a reputation as slow-loading components. However, since .jars

were introduced, an applet is usually delivered as a single file that

has a size similar to an image file (hundreds of kilobytes to several

megabytes).

Java system libraries and runtimes are backwards-compatible, allowing one to write code that runs both on current and on future versions of the Java virtual machine.

Similar technologies

Many Java developers, blogs and magazines recommended that the Java Web Start technology be used in place of applets. Java Web Start allowed the launching of unmodified applet code, which then ran in a separate window (not inside the invoking browser).

A Java Servlet is sometimes informally compared to be "like" a server-side applet, but it is different in its language, functions, and in each of the characteristics described here about applets.

Embedding into a web page

The applet would be displayed on the web page by making use of the deprecated applet HTML element, or the recommended object element. The embed element can be used with Mozilla family browsers (embed was deprecated in HTML 4 but is included in HTML 5). This specifies the applet's source and location. Both object and embed tags can also download and install Java virtual machine (if required) or at least lead to the plugin page. applet and object

tags also support loading of the serialized applets that start in some

particular (rather than initial) state. Tags also specify the message

that shows up in place of the applet if the browser cannot run it due to

any reason.

However, despite object being officially a recommended tag in 2010, the support of the object tag was not yet consistent among browsers and Sun kept recommending the older applet tag for deploying in multibrowser environments, as it remained the only tag consistently supported by the most popular browsers. To support multiple browsers, using the object

tag to embed an applet would require JavaScript (that recognizes the

browser and adjusts the tag), usage of additional browser-specific tags

or delivering adapted output from the server side.

The Java browser plug-in relied on NPAPI, which nearly all web browser vendors have removed support for, or do not implement, due to its age and security issues. In January 2016, Oracle announced that Java runtime environments based on JDK 9 will discontinue the browser plug-in.

Advantages

A Java applet could have any or all of the following advantages:

- It was simple to make it work on FreeBSD, Linux, Microsoft Windows and macOS – that is, to make it cross-platform. Applets were supported by most web browsers through the first decade of the 21st century; since then, however, most browsers have dropped applet support for security reasons.

- The same applet would work on "all" installed versions of Java at the same time, rather than just the latest plug-in version only. However, if an applet requires a later version of the Java Runtime Environment (JRE) the client would be forced to wait during the large download.

- Most web browsers cached applets so they were quick to load when returning to a web page. Applets also improved with use: after a first applet is run, the JVM was already running and subsequent applets started quickly (the JVM will need to restart each time the browser starts afresh). JRE versions 1.5 and greater restarted the JVM when the browser navigates between pages, as a security measure which removed that performance gain.

- It moved work from the server to the client, making a web solution more scalable with the number of users/clients.

- If a standalone program (like Google Earth) talks to a web server, that server normally needs to support all prior versions for users who have not kept their client software updated. In contrast, a browser loaded (and cached) the latest applet version, so there is no need to support legacy versions.

- Applet naturally supported changing user state, such as figure positions on the chessboard.

- Developers could develop and debug an applet directly simply by creating a main routine (either in the applet's class or in a separate class) and calling init() and start() on the applet, thus allowing for development in their favorite Java SE development environment. All one had to do was to re-test the applet in the AppletViewer program or a web browser to ensure it conforms to security restrictions.

- An untrusted applet had no access to the local machine and can only access the server it came from. This makes applets much safer to run than the native executables that they would replace. However, a signed applet could have full access to the machine it is running on, if the user agreed.

- Java applets were fast, with similar performance to natively installed software.

Disadvantages

Java applets had the following disadvantages compared to other client-side web technologies:

- Java applets would depend on a Java Runtime Environment (JRE), a complex and heavy-weight software package. They also normally required a plug-in for the web browser. Some organizations only allow software installed by an administrator. As a result, users were unable to view applets unless one was important enough to justify contacting the administrator to request installation of the JRE and plug-in.

- If an applet requires a newer JRE than available on the system, the user running it the first time will need to wait for the large JRE download to complete.

- Mobile browsers on iOS or Android, never run Java applets at all. Even before the deprecation of applets on all platforms, desktop browsers phased out Java applet support concurrently with the rise of mobile operating systems.

- There was no standard to make the content of applets available to screen readers. Therefore, applets harmed the accessibility of a web site to users with special needs.

- As with any client-side scripting, security restrictions made it difficult or even impossible for some untrusted applets to achieve their desired goals. Only by editing the java.policy file in the JAVA JRE installation could one grant access to the local filesystem or system clipboard, or to network sources other than the one that served the applet to the browser.

- Most users did not care about the difference between untrusted and trusted applets, so this distinction did not help much with security. The ability to run untrusted applets was eventually removed entirely to fix this, before all applets were removed.

Sun made considerable efforts to ensure compatibility is maintained between Java versions as they evolve, enforcing Java portability by law if required. Oracle seems to be continuing the same strategy.

1997: Sun vs Microsoft

The 1997 lawsuit, was filed after Microsoft created a modified Java Virtual Machine of their own, which shipped with Internet Explorer. Microsoft added about 50 methods and 50 fields into the classes within the java.awt, java.lang, and java.io packages. Other modifications included removal of RMI capability and replacement of Java Native Interface from JNI to RNI, a different standard. RMI was removed because it only easily supports Java to Java communications and competes with Microsoft DCOM technology. Applets that relied on these changes or just inadvertently used them worked only within Microsoft's Java system. Sun sued for breach of trademark, as the point of Java was that there should be no proprietary extensions and that code should work everywhere. Microsoft agreed to pay Sun $20 million, and Sun agreed to grant Microsoft limited license to use Java without modifications only and for a limited time.

2002: Sun vs Microsoft

Microsoft continued to ship its own unmodified Java virtual machine. Over the years it became extremely outdated yet still default for Internet Explorer. A later study revealed that applets of this time often contain their own classes that mirror Swing and other newer features in a limited way. In 2002, Sun filed an antitrust lawsuit, claiming that Microsoft's attempts at illegal monopolization had harmed the Java platform. Sun demanded Microsoft distribute Sun's current, binary implementation of Java technology as part of Windows, distribute it as a recommended update for older Microsoft desktop operating systems and stop the distribution of Microsoft's Virtual Machine (as its licensing time, agreed in the prior lawsuit, had expired). Microsoft paid $700 million for pending antitrust issues, another $900 million for patent issues and a $350 million royalty fee to use Sun's software in the future.

Security

There were two applet types with very different security models: signed applets and unsigned applets. Starting with Java SE 7 Update 21 (April 2013) applets and Web-Start Apps are encouraged to be signed with a trusted certificate, and warning messages appear when running unsigned applets. Further, starting with Java 7 Update 51 unsigned applets were blocked by default; they could be run by creating an exception in the Java Control Panel.

Unsigned

Limits on unsigned applets were understood as "draconian": they have no access to the local filesystem and web access limited to the applet download site; there are also many other important restrictions. For instance, they cannot access all system properties, use their own class loader, call native code, execute external commands on a local system or redefine classes belonging to core packages included as part of a Java release. While they can run in a standalone frame, such frame contains a header, indicating that this is an untrusted applet. Successful initial call of the forbidden method does not automatically create a security hole as an access controller checks the entire stack of the calling code to be sure the call is not coming from an improper location.

As with any complex system, many security problems have been discovered and fixed since Java was first released. Some of these (like the Calendar serialization security bug) persisted for many years with nobody being aware. Others have been discovered in use by malware in the wild.

Some studies mention applets crashing the browser or overusing CPU resources but these are classified as nuisances and not as true security flaws. However, unsigned applets may be involved in combined attacks that exploit a combination of multiple severe configuration errors in other parts of the system. An unsigned applet can also be more dangerous to run directly on the server where it is hosted because while code base allows it to talk with the server, running inside it can bypass the firewall. An applet may also try DoS attacks on the server where it is hosted, but usually people who manage the web site also manage the applet, making this unreasonable. Communities may solve this problem via source code review or running applets on a dedicated domain.

The unsigned applet can also try to download malware hosted on originating server. However it could only store such file into a temporary folder (as it is transient data) and has no means to complete the attack by executing it. There were attempts to use applets for spreading Phoenix and Siberia exploits this way, but these exploits do not use Java internally and were also distributed in several other ways.

Signed

A signed applet contains a signature that the browser should verify through a remotely running, independent certificate authority server. Producing this signature involves specialized tools and interaction with the authority server maintainers. Once the signature is verified, and the user of the current machine also approves, a signed applet can get more rights, becoming equivalent to an ordinary standalone program. The rationale is that the author of the applet is now known and will be responsible for any deliberate damage. This approach allows applets to be used for many tasks that are otherwise not possible by client-side scripting. However, this approach requires more responsibility from the user, deciding whom he or she trusts. The related concerns include a non-responsive authority server, wrong evaluation of the signer identity when issuing certificates, and known applet publishers still doing something that the user would not approve of. Hence signed applets that appeared from Java 1.1 may actually have more security concerns.

Self-signed

Self-signed applets, which are applets signed by the developer themselves, may potentially pose a security risk; java plugins provide a warning when requesting authorization for a self-signed applet, as the function and safety of the applet is guaranteed only by the developer itself, and has not been independently confirmed. Such self-signed certificates are usually only used during development prior to release where third-party confirmation of security is unimportant, but most applet developers will seek third-party signing to ensure that users trust the applet's safety.

Java security problems are not fundamentally different from similar problems of any client-side scripting platform. In particular, all issues related to signed applets also apply to Microsoft ActiveX components.

As of 2014, self-signed and unsigned applets are no longer accepted by the commonly available Java plugins or Java Web Start. Consequently, developers who wish to deploy Java applets have no alternative but to acquire trusted certificates from commercial sources.