From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

|

|||

| Definition | Defined in 1997 by the WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA as the "partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons."[1] | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Areas | Most common in 27 countries in Africa, as well as in Yemen and Iraqi Kurdistan[2] | ||

| Numbers | 133 million in those countries[3] | ||

| Age | Days after birth to puberty[4] | ||

| Prevalence | |||

|

|||

|

|||

| Legislation | |||

|

|||

Female genital mutilation (FGM), also known as female genital cutting and female circumcision, is the ritual removal of some or all of the external female genitalia. Typically carried out by a traditional circumciser using a blade or razor (with or without anaesthesia), FGM is primarily performed in 27 African countries, Yemen and Iraqi Kurdistan, and found elsewhere in Asia, the Middle East, and among diaspora communities around the world.[7] The age at which it is conducted varies from days after birth to puberty; in half the countries for which national figures are available, most girls are cut before the age of five.[8]

The procedures differ according to the ethnic group. They include removal of the clitoral hood and clitoral glans (the visible part of the clitoris), removal of the inner labia and, in the most severe form (known as infibulation), removal of the inner and outer labia and closure of the vulva. In this last procedure, a small hole is left for the passage of urine and menstrual fluid, and the vagina is opened for intercourse and opened further for childbirth. Health effects depend on the procedure, but can include recurrent infections, chronic pain, cysts, an inability to get pregnant, complications during childbirth and fatal bleeding.[9] There are no known health benefits.[10]

The practice is rooted in gender inequality, attempts to control women's sexuality, and ideas about purity, modesty and aesthetics. It is usually initiated and carried out by women, who see it as a source of honour, and who fear that failing to have their daughters and granddaughters cut will expose the girls to social exclusion.[11] Over 130 million women and girls have experienced FGM in the 29 countries in which it is concentrated.[3] The United Nations Population Fund estimates that 20 percent of affected women have been infibulated, a practice found largely in northeast Africa, particularly Djibouti, Eritrea, Somalia and northern Sudan.[12][13]

FGM has been outlawed or restricted in most of the countries in which it occurs, but the laws are poorly enforced.[14] There have been international efforts since the 1970s to persuade practitioners to abandon it, and in 2012 the United Nations General Assembly, recognizing FGM as a human-rights violation, voted unanimously to intensify those efforts.[15] The opposition is not without its critics, particularly among anthropologists. Eric Silverman writes that FGM has become one of anthropology's central moral topics, raising difficult questions about cultural relativism, tolerance and the universality of human rights.[16]

Terminology

English

Until the 1980s FGM was widely known as female circumcision, which implied an equivalence in severity with male circumcision.[17] The Kenya Missionary Council began referring to it as the sexual mutilation of women in 1929, following the lead of Marion Scott Stevenson, a Church of Scotland missionary.[18] References to it as mutilation increased throughout the 1970s.[19] Anthropologist Rose Oldfield Hayes called it female genital mutilation in 1975 in the title of a paper, and in 1979 Austrian-American researcher Fran Hosken called it mutilation in her influential The Hosken Report: Genital and Sexual Mutilation of Females.[20]

The Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children and the World Health Organization (WHO) began referring to it as female genital mutilation in 1990 and 1991 respectively,[21] and in April 1997 the WHO, United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF) and United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA) issued a joint statement using that term. Other terms include female genital cutting (FGC) and female genital mutilation/cutting (FGM/C), preferred by those who work with practitioners.[22]

Local terms

The many variants of FGM are reflected in dozens of local terms in countries where it is common.[23] These often refer to purification. A common Arabic term for purification has the root t-h-r, used for male and female circumcision (tahur and tahara).[24] In the Bambara language, spoken mostly in Mali, FGM is known as bolokoli ("washing your hands") and in the Igbo language in Eastern Nigeria as isa aru or iwu aru ("having your bath" – as in "a young woman must 'have her bath' before she has a baby").[25]Sunna circumcision usually refers to clitoridectomy, but is also used for the more severe forms; sunna means "path or way" in Arabic and refers to the tradition of Muhammad, although none of the procedures are required within Islam.[26] The term infibulation derives from fibula, Latin for clasp; the Ancient Romans reportedly fastened clasps through the foreskins or labia of slaves to prevent sexual intercourse.[27] The surgical infibulation of women came to be known as pharaonic circumcision in Sudan, but as Sudanese circumcision in Egypt.[27] In Somalia it is known simply as qodob ("to sew up").[28]

Procedures, health effects

Circumcisers, methods

Anatomy of the vulva, showing the clitoral glans, clitoral crura, corpora cavernosa and vestibular bulbs

The procedures are generally performed by a traditional circumciser in the girls' homes, with or without anaesthesia. The circumciser is usually an older woman, but in communities where the male barber has assumed the role of health worker he will perform FGM too.[29] Health professionals are often involved in Egypt, Sudan and Kenya; according to a 2008 survey in Egypt, 77 percent of FGM procedures there were performed by medical professionals, often physicians.[30]

When traditional circumcisers are involved, non-sterile cutting devices are likely to be used, including knives, razors, scissors, glass, sharpened rocks and fingernails.[31] A nurse in Uganda, quoted in 2007 in The Lancet, said that a circumciser would use one knife to cut up to 30 girls at a time.[32] Depending on the involvement of healthcare professionals, the procedures may include a local or general anaesthetic, or neither. Women in Egypt reported in 1995 that a local anaesthetic had been used on their daughters in 60 percent of cases, a general in 13 percent and neither in 25 percent.[33]

Classification

Typologies

The WHO, UNICEF and UNFPA issued a joint statement in April 1997 defining female genital mutilation as "all procedures involving partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs whether for cultural or other non-therapeutic reasons."[34]The procedures vary considerably according to ethnicity and individual practitioners. In a survey in Niger in 1998, women responded with over 50 different terms when asked what was done to them.[23] Translation problems are compounded by the women's confusion over which type of FGM they experienced, or even whether they experienced it. Several studies have shown survey responses to be unreliable. A study in Ghana in 2003, for example, found that women had changed their responses during surveys; when asked if they had undergone FGM, four percent said no in 1995 but yes in 2000, and 11 percent switched in the other direction.[35]

Standard questionnaires ask women whether they have undergone the following: (1) cut, no flesh removed (pricking or symbolic circumcision); (2) cut, some flesh removed; (3) sewn closed; and (4) type not determined/unsure/doesn't know.[36] The most common procedures fall within the "cut, some flesh removed" category, and involve complete or partial removal of the clitoral glans.[37]

WHO Types I–III

The WHO has created a more detailed typology that describes how much tissue was removed: Types I–III and Type IV for symbolic circumcision and miscellaneous procedures.[38]

Type I is subdivided into Ia, the removal of the clitoral hood (rarely, if ever performed alone),[39] and the more common Ib (clitoridectomy), the complete or partial removal of the clitoral glans and clitoral hood.[40] (When discussing FGM, the WHO uses the word clitoris to refer to the clitoral glans, the external part of the clitoris.)[41] Susan Izett and Nahid Toubia write: "[T]he clitoris is held between the thumb and index finger, pulled out and amputated with one stroke of a sharp object."[42]

Type II (excision) is the complete or partial removal of the inner labia, with or without removal of the clitoral glans and outer labia. (Excision in French usually means any form of FGM.) Type II is subdivided into Type IIa, removal of the inner labia; IIb, removal of the clitoral glans and inner labia; and IIc, removal of the clitoral glans, inner and outer labia.[43]

Type III (infibulation), corresponding to the "sewn closed" category, is the removal of the external genitalia and the fusion of the wound. The inner and/or outer labia are cut away, with or without removal of the clitoral glans. Type IIIa is the removal and closure of the inner labia and IIIb of the outer labia.[44] According to one 2008 estimate, over eight million women in Africa have experienced infibulation, which is found largely in Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Somalia and Sudan in northeast Africa.[13] According to the UNFPA, 20 percent of affected women have been infibulated.[12]

Comfort Momoh, a midwife who specializes in the care of women who have undergone FGM, writes of Type III: "[E]lderly women, relatives and friends secure the girl in the lithotomy position. A deep incision is made rapidly on either side from the root of the clitoris to the fourchette, and a single cut of the razor excises the clitoris and both the labia majora and labia minora."[45] In Somalia the clitoral glans is removed and shown to the girl's senior female relatives, who decide whether enough has been amputated; after this the labia are removed.[46]

A single hole of 2–3 mm is left for the passage of urine and menstrual fluid by inserting something, such as a twig, into the wound.[47] The vulva is closed with surgical thread, agave or acacia thorns, or covered with a poultice such as raw egg, herbs and sugar.[48] The parts that have been removed might be placed in a pouch for the girl to wear.[49] To help the tissue bond, the girl's legs are tied together, usually from ankle to hip, for anything up to six weeks; the bindings are usually loosened after a week and may be removed after two.[50] Momoh writes:

[As a result, the entrance to the vagina] is obliterated by a drum of skin extending across the orifice except for a small hole. Circumstances at the time may vary; the girl may struggle ferociously, in which case the incisions may become uncontrolled and haphazard. The girl may be pinned down so firmly that bones may fracture.[45]If the girl's family regard the remaining hole as too large, the procedure is repeated.[51] The vagina is opened for sexual intercourse, for the first time either by a midwife with a knife or by the woman's husband with his penis. In some areas, including Somaliland, female relatives of the bride and groom might watch the opening of the vagina to check that the girl is a virgin.[52] Psychologist Hanny Lightfoot-Klein interviewed hundreds of women and men in Sudan in the 1980s about sexual intercourse with Type III:

The penetration of the bride's infibulation takes anywhere from 3 or 4 days to several months. Some men are unable to penetrate their wives at all (in my study over 15%), and the task is often accomplished by a midwife under conditions of great secrecy, since this reflects negatively on the man's potency. Some who are unable to penetrate their wives manage to get them pregnant in spite of the infibulation, and the woman's vaginal passage is then cut open to allow birth to take place. ... Those men who do manage to penetrate their wives do so often, or perhaps always, with the help of the "little knife." This creates a tear which they gradually rip more and more until the opening is sufficient to admit the penis.[53]The woman is opened further for childbirth and closed afterwards, a process known as defibulation (or deinfibulation) and reinfibulation. Reinfibulation can involve cutting the vagina again to restore the size of the first infibulation; this might be performed before marriage, and after childbirth, divorce and widowhood.[54]

Type IV

Type IV is defined as "[a]ll other harmful procedures to the female genitalia for non-medical purposes, for example: pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterization."[1] It includes nicking of the clitoris (symbolic circumcision), burning or scarring the genitals, and introducing substances into the vagina to tighten it.[55] Labia stretching is also categorized as Type IV.[56] Common in southern and eastern Africa, the practice is supposed to enhance sexual pleasure for the man and add to the sense of a woman as a closed space. From the age of eight girls are encouraged to stretch their inner labia using sticks and massage. Girls in Uganda are told they may have difficulty giving birth without stretched labia.[57]A definition of FGM from the WHO in 1995 included gishiri cutting and angurya cutting, found in Nigeria and Niger. These were removed from the WHO's 2008 definition because of insufficient information about prevalence and consequences.[56] Gishiri cutting involves cutting the vagina's front or back wall with a blade or penknife, performed in response to infertility, obstructed labour and several other conditions; over 30 percent of women with gishiri cuts in a study by Nigerian physician Mairo Usman Mandara had vesicovaginal fistulae. Angurya cutting is excision of the hymen, usually performed seven days after birth.[58]

Complications

Short-term and late

FGM can cause serious adverse consequences to girls' and women's physical and emotional health.[59] It has no known health benefits.[10] The short-term and late complications depend on the type of FGM, whether the practitioner had medical training, and whether she used antibiotics and unsterilized or surgical single-use instruments. In the case of Type III, other factors include how small a hole was left for the passage of urine and menstrual blood, whether surgical thread was used instead of agave or acacia thorns, and whether the procedure was performed more than once (for example, to close an opening regarded as too wide or re-open one too small).[9]

FGM ceremony in Indonesia

— Stephanie Sinclair, The New York Times[60]

Short-term complications can include fatal bleeding, anaemia, acute urinary retention, urinary infection, wound infection, septicaemia, tetanus, gangrene, necrotizing fasciitis (flesh-eating disease) and endometritis.[59][61][9][62] It is not known how many girls and women die as a result of the practice, because complications may not be recognized or reported.[63][64] The practitioners' use of shared instruments is thought to aid the transmission of hepatitis B, hepatitis C and HIV, although no epidemiological studies have shown this.[64]

Long-term complications include epidermoid cysts that may become infected, and neuroma formation (growth of nerve tissue) involving nerves that supplied the clitoris.[65] An infibulated girl may be left with an opening as small as 2–3 mm, which can cause difficult and painful urination. Urine may collect underneath the scar and cause small stones to form. The opening is larger in women who are sexually active or have given birth by vaginal delivery, but the urethra opening may still be obstructed by scar tissue. Painful periods are common because of the obstruction to the menstrual flow, and blood can stagnate in the vagina and uterus.[9] Vesicovaginal or rectovaginal fistulae can develop (holes that allow urine or faeces to seep into the vagina). This and other damage to the urethra and bladder can lead to infections and incontinence, pain during sexual intercourse and infertility.[62]

Pregnancy, childbirth

FGM may place women at higher risk of problems during pregnancy and childbirth. These are more common with the more extensive FGM procedures.[9] In women with vesicovaginal or rectovaginal fistulae, it is difficult to obtain clear urine samples as part of prenatal care, making the diagnosis of conditions such as pre-eclampsia harder.[62] Cervical evaluation during labour may be impeded and labour prolonged. Third-degree laceration (tears), anal-sphincter damage and emergency caesarean section are more common in infibulated women.[9]Neonatal mortality is increased. The WHO estimated in 2006 that an additional 10–20 babies die per 1,000 deliveries as a result of FGM. The estimate was based on a study conducted on 28,393 women attending delivery wards at 28 obstetric centres in Burkina Faso, Ghana, Kenya, Nigeria, Senegal and Sudan. In those settings all types of FGM were found to pose an increased risk of death to the baby: 15 percent higher for Type I, 32 percent for Type II and 55 percent for Type III.[66]

Psychological effects, sexual function

According to a systematic review in 2015 there is little high-quality information available on the psychological effects of FGM. Several small studies have concluded that women with FGM were suffering from anxiety, depression and post-traumatic stress disorder.[64] Feelings of shame and betrayal can develop when women leave the culture that practises FGM and learn that their condition is not the norm, but within the practising culture they may view their FGM with pride, because for them it signifies beauty, respect for tradition, chastity and hygiene.[9]Studies on sexual function have also been small.[64] A systematic review and meta-analysis in 2013 examined 15 studies involving 12,671 women from seven countries. The analysis concluded that women with FGM were twice as likely to report no sexual desire and 52 percent more likely to report dyspareunia (painful sexual intercourse). One third reported reduced sexual feelings.[67]

Distribution

Prevalence

UNICEF reported in November 2014 that prevalence rates for sub-Saharan Africa were 39 percent for women and 17 percent for girls aged 0–14; for Eastern and Southern Africa 44 and 14 percent, and for West and Central Africa 31 and 17 percent.[5] As of 2013[update], Egypt, Ethiopia and Nigeria had the highest number of women and girls living with FGM: 27.2 million, 23.8 million and 19.9 million respectively.[69]

Prevalence figures are based on household surveys known as Demographic and Health Surveys (DHS), developed by Macro International (now ICF International) and funded mainly by the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), and Multiple Indicator Cluster Surveys (MICS), which are conducted with financial and technical assistance from UNICEF.[70] These have been carried out in Africa, Asia, Latin America and elsewhere roughly every five years, since 1984 and 1995 respectively.[71] The questionnaires ask about issues such as HIV/AIDs, family planning, literacy, domestic violence, nutrition and, in some countries, FGM.[72]

The first survey to include questions about FGM was the 1989–1990 DHS in northern Sudan, and the first publication to estimate FGM prevalence based on DHS data (in seven countries) was by Dara Carr of Macro International in 1997.[73] A UNICEF report based on over 70 of these surveys concluded in 2013 that FGM was concentrated in 27 African countries, Yemen and Iraqi Kurdistan,[74] and that 133 million women and girls in those 29 countries had experienced it.[3]

Outside the 29 key countries, FGM has been documented in India, the United Arab Emirates, among the Bedouin in Israel, and reported by anecdote in Colombia, Congo, Oman, Peru and Sri Lanka.[75] It is also practised in Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Indonesia and Malaysia, and within immigrant communities around the world, including in Australia, New Zealand, Europe, Scandinavia, the United States and Canada.[76]

Ethnicity and other factors

A country's national prevalence often reflects a high sub-national prevalence among certain ethnicities, rather than a widespread practice.[77] In Iraq, for example, FGM is found mostly among the Kurds in Erbil (58 percent prevalence within age group 15–49), Sulaymaniyah (54 percent) and Kirkuk (20 percent), giving the country a national prevalence of eight percent.[78]The practice is sometimes an ethnic marker, but may differ along national lines. In the northeastern regions of Ethiopia and Kenya, which share a border with Somalia, the Somali people practise FGM at around the same rate as they do in Somalia.[80] But in Guinea all Fulani women responding to a survey in 2012 said they had experienced FGM,[81] against 12 percent of the Fulani in Chad, while in Nigeria the Fulani are the only large ethnic group in the country not to practise it.[82]

The surveys have found FGM to be more common in rural areas, less common in most countries among girls from the wealthiest homes, and (except in Sudan and Somalia) less common in girls whose mothers had access to primary or secondary/higher education. In Somalia and Sudan the situation was reversed: in Somalia the mothers' access to secondary/higher education was accompanied by a rise in prevalence of FGM in their daughters, and in Sudan access to any education was accompanied by a rise.[83]

Type of FGM

The surveys ask several questions about the type of FGM the women have undergone, including:[84]Most women who have undergone FGM have experienced one of the "cut, some fleshed removed" procedures, which embrace WHO Types I and II.[37] Types I and II are both performed in Egypt.[85] Mackie wrote in 2003 that Type II was more common there,[86] while a 2011 study identified Type I as more common.[87] In Nigeria Type I is usually found in the south and the more severe forms in the north.[88]

- Was the genital area just nicked/cut without removing any flesh?

- Was any flesh (or something) removed from the genital area?

- Was your genital area sewn?

Type III (infibulation) is concentrated in northeastern Africa, particularly Djibouti, Eritrea, Somalia and Sudan.[89] In surveys in 2002–2006, 30 percent of cut girls in Djibouti had experienced Type III, 38 percent in Eritrea and 63 percent in Somalia.[90] There is also a high prevalence of infibulation among girls in Niger and Senegal,[91] and in 2013 it was estimated that in Nigeria three percent of the 0–14 age group had been infibulated.[92] The type of procedure is often linked to ethnicity. In Eritrea, for example, a survey in 2002 found that all Hedareb girls had been infibulated, compared with two percent of the Tigrinya, most of whom fell into the "cut, no flesh removed" category.[93]

Age conducted

FGM is mostly performed from shortly after birth to age 15.[4] The variation signals that the practice is often not a rite of passage between childhood and adulthood.[94]In half the countries for which national figures were available in 2000–2010, most girls had been cut by the age of five.[8] Over 80 percent of girls who experience FGM are cut before that age in Nigeria, Mali, Eritrea, Ghana and Mauritania. The percentage is reversed in Somalia, Egypt, Chad and the Central African Republic, where over 80 percent (of those cut) are cut between five and 14.[95] A 1997 survey found that 76 percent of girls in Yemen had been cut within two weeks of birth.[96] Just as the type of FGM is linked to ethnicity, so is the mean age; in Kenya, for example, the Kisi cut around age 10 and the Kamba at 16.[97]

Changes in prevalence

In 2013 UNICEF reported a downward trend in over half the 29 key countries in the 15–19 group compared to women aged 45–49.[98] Little difference was found in countries with very high prevalence, but the rate of FGM had declined in countries with lower prevalence, or less severe forms of FGM were being practised.[99] According to UNICEF in July 2014, the likelihood of a girl experiencing FGM was overall one third lower than 30 years ago.[100] Despite this, because of population growth, the numbers affected by FGM in the key 29 countries will increase from 133 million to 196 million by 2050, if the rate of decline as of 2014[update] continues.[101]Women who respond to surveys on FGM are reporting events experienced years ago, so prevalence figures for the 15–49 group do not reflect current trends.[103] UNICEF bases its figures on the 15–49 group because girls are generally at risk until they are 14.[104] An additional complication in judging prevalence among girls 14 and under is that women might not report that their daughters have been cut in countries running campaigns against FGM.[105]

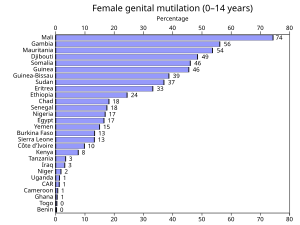

In 2010 the DHS and MICS surveys began asking women about the FGM status of all their living daughters.[106] As of November 2014[update] (right), the surveys suggested a prevalence for the 0–14 age group of 0.3 percent in Benin at the lowest (7 percent for the 15–49 group) to 74 percent in Mali (89 percent for 15–49).[5]

In a study in Egypt in 2008–2010 (FGM was banned there by decree in 2007 and criminalized in 2008), 4,158 women and girls aged 5–25, who presented to three departments at Sohag and Qena University Hospitals, replied to a questionnaire about FGM. According to the researchers, the most common form of FGM in Egypt is Type I. The study found that, between 2000 and 2009, 3,711 of the subjects had undergone FGM, giving a prevalence rate of 89.2 percent. The incidence rate was 9.6 percent in 2000. It began to fall in 2006 and by 2009 had declined to 7.7 percent. After 2007 most of the procedures were conducted by general practitioners. The researchers suggested that the criminalization of FGM had deterred gynaecologists, so general practitioners were performing it instead.[87]

Reasons

Support from women

Dahabo Musa, a Somali woman, described infibulation in a 1988 poem as the "three feminine sorrows": the procedure itself, the wedding night when the woman is cut open, then childbirth when she is cut again.[107] Despite the evident suffering, it is women who organize all forms of FGM, including infibulation. Anthropologist Rose Oldfield Hayes wrote in 1975 that educated Sudanese men living in cities who did not want their daughters to be infibulated (preferring clitoridectomy) would find the girls had been sewn up after their grandmothers arranged a visit to relatives.[108]Gerry Mackie compares FGM to footbinding. Like FGM, footbinding was carried out on young girls, nearly universal where practised, tied to ideas about honour, chastity and appropriate marriage, and supported by women.[109]

1996 Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography

A series of 13 photographs of an FGM ceremony in Kenya won the award:

Photograph 5

Photograph 7

Photograph 10

Photograph 13

Photograph 5

Photograph 7

Photograph 10

Photograph 13

— Stephanie Walsh, Newhouse News Service[110]

Practitioners see the procedures as marking not only community boundaries but also gender difference. According to this view, FGM demasculinizes women, while male circumcision defeminizes men.[111] Fuambai Ahmadu, an anthropologist and member of the Kono people of Sierra Leone, who underwent clitoridectomy as an adult during a Sande society initiation, argues that the idea of the clitoris as important to female sexuality is a male-centred assumption. African female symbolism revolves instead around the concept of the womb.[112] Infibulation draws on that idea of enclosure and fertility.

"[G]enital cutting completes the social definition of a child's sex by eliminating external traces of androgyny," writes Janice Boddy. "The female body is then covered, closed, and its productive blood bound within; the male body is unveiled, opened and exposed."[113]

In communities where infibulation is common, there is a preference for women's genitals to be smooth, dry and without odour, and both women and men may find the natural vulva repulsive.[114] Men seem to enjoy the effort of penetrating an infibulation.[115] There is also a belief, because of the smooth appearance of an infibulated vulva, that infibulation increases hygiene.[116] Women regularly introduce substances into the vagina to reduce lubrication, including leaves, tree bark, toothpaste and Vicks menthol rub. The WHO includes this practice within Type IV FGM, because the added friction during intercourse can cause lacerations and increase the risk of infection.[117]

Common reasons for FGM cited by women in surveys are social acceptance, religion, hygiene, preservation of virginity, marriageability and enhancement of male sexual pleasure.[118] In a study in northern Sudan, published in 1983, only 558 (17.4 percent) of 3,210 women opposed FGM, and most preferred excision and infibulation over clitoridectomy.[119] Attitudes are slowly changing. In Sudan in 2010 42 percent of women who had heard of FGM said the practice should continue.[120] In several surveys since 2006, over 50 percent of women in Mali, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Somalia, Gambia and Egypt supported FGM's continuance, while elsewhere in Africa, Iraq and Yemen most said it should end, though in several countries only by a narrow margin.[121]

Social obligation

Molly Melching in 2007 on the 10th anniversary of the abandonment of FGM by Malicounda Bambara, Senegal

Against the argument that women willingly choose FGM for their daughters, UNICEF calls the practice a "self-enforcing social convention" to which families feel they must conform to avoid uncut daughters facing social exclusion.[122]

Ellen Gruenbaum reports that, in the 1970s, cut girls from an Arab ethnic group in Sudan would mock uncut girls from the Zabarma people, shouting at them Ya, Ghalfa! ("Hey, unclean!"). The Zabarma girls would respond with their own taunt, Ya, mutmura! (a mutmara was a storage pit for grain that was continually opened and closed, like an infibulated woman). But the Zabarma girls felt the pressure, asking their mothers, "What's the matter? Don't we have razor blades like the Arabs?"[123]

Because of poor access to information, and because circumcisers downplay the causal connection, women may not associate the health consequences with the procedure. Lala Baldé, president of a women's association in Medina Cherif, a village in Senegal, told Mackie in 1998 that when girls fell ill or died, it was attributed to evil spirits. When informed of the causal relationship between FGM and ill health, Mackie writes, the women broke down and wept. He argues that surveys taken before and after this sharing of information would show very different levels of support for FGM.[124]

The American non-profit group Tostan, founded by Molly Melching in 1991, has introduced community-empowerment programmes in several countries that focus on literacy, education about healthcare and local democracy, giving women the tools to make their own decisions.[125] In 1997, using the Tostan programme, Malicounda Bambara in Senegal became the first village to abandon FGM, and by 2014 over 7,000 communities in eight countries had pledged to abandon FGM and child marriage.[126] A UNFPA-UNICEF joint programme, underway in 15 African countries as of 2014[update], is modelled along similar lines.[122]

Religion

Surveys have shown a widespread belief, particularly in Mali, Mauritania, Guinea and Egypt, that FGM is a religious requirement.[128] Gruenbaum has argued that practitioners may not distinguish between religion, tradition and chastity, making it difficult to interpret the data.[129] As part of UNFPA–UNICEF's joint programme, 20,941 religious and traditional leaders made public declarations between 2008 and 2013 delinking their religions from the practice, and religious leaders issued 2,898 edicts against it.[130]

Although FGM's origins in northeastern Africa are pre-Islamic, the practice became associated with Islam because of that religion's focus on female chastity and seclusion.[131] There is no mention of it in the Quran. It is praised in several hadith (sayings attributed to Muhammad) as noble but not required, along with advice that the milder forms are kinder to women.[132] In 2007 the Al-Azhar Supreme Council of Islamic Research in Cairo ruled that FGM had "no basis in core Islamic law or any of its partial provisions."[133]

FGM is also practised by animist groups, particularly in Guinea and Mali, and by Christians.[134] In Niger, for example, 55 percent of Christian women and girls have experienced FGM, compared with two percent of their Muslim counterparts.[135] There is no mention of FGM in the Bible, and Christian missionaries in Africa were among the first to object to it.[136] The only Jewish group known to have practised it are the Beta Israel of Ethiopia; Judaism requires male circumcision, but does not allow FGM.[137]

History

Antiquity

Spell 1117

But if a man wants to know how to live, he should recite it [a magical spell] every day, after his flesh has been rubbed with the b3d [unknown substance] of an uncircumcised girl ['m't] and the flakes of skin [šnft] of an uncircumcised bald man.

The origins of the practice are unknown.[139] Gerry Mackie has suggested that it began with the Meroite civilization in present-day Sudan; he writes that its east-west, north-south contiguous distribution in Africa intersects in Sudan, and speculates that infibulation originated there with imperial polygyny, before the rise of Islam, to increase confidence in paternity.[140] Historian Mary Knight writes that there may be a reference to an uncircumcised girl ('m't), written in hieroglyphs, in what is known as Spell 1117 of the Coffin Texts:

The spell was found on the sarcophagus of Sit-hedjhotep, now in the Egyptian Museum, and dates to Egypt's Middle Kingdom, c. 1991–1786 BCE. (Paul F. O'Rourke argues that 'm't probably refers instead to a menstruating woman.)[141] The proposed circumcision of an Egyptian girl, Tathemis, is mentioned on a Greek papyrus from 163 BCE in the British Museum:

Sometime after this, Nephoris [Tathemis's mother] defrauded me, being anxious that it was time for Tathemis to be circumcised, as is the custom among the Egyptians. She asked that I give her 1,300 drachmae ... to clothe her ... and to provide her with a marriage dowry ... if she didn't do each of these or if she did not circumcise Tathemis in the month of Mecheir, year 18 [163 BCE], she would repay me 2,400 drachmae on the spot.[142]The examination of mummies has shown no evidence of FGM. Citing the Australian pathologist Grafton Elliot Smith, who examined hundreds of mummies in the early 20th century, Knight writes that the genital area may resemble Type III, because during mummification the skin of the outer labia was pulled toward the anus to cover the pudendal cleft, possibly to prevent sexual violation. It was similarly not possible to determine whether Types I or II had been performed, because soft tissues had been removed by the embalmers or had deteriorated.[143]

This is one of the customs most zealously pursued by them [the Egyptians]: to raise every child that is born and to circumcise [peritemnein] the males and excise [ektemnein] the females ...

The Greek geographer Strabo (c. 64 BCE – c. 23 CE) wrote about FGM after visiting Egypt around 25 BCE (right).[144] The philosopher Philo of Alexandria (c. 20 BCE – 50 CE) also made reference to it: "the Egyptians by the custom of their country circumcise the marriageable youth and maid in the fourteenth (year) of their age, when the male begins to get seed, and the female to have a menstrual flow."[145] It is mentioned briefly in a work attributed to the Greek physician Galen (129 – c. 200 CE): "When [the clitoris] sticks out to a great extent in their young women, Egyptians consider it appropriate to cut it out."[146]

Another Greek physician, Aëtius of Amida (mid-5th to mid-6th century CE), offered more detail in book 16 of his Sixteen Books on Medicine, citing the physician Philomenes. The procedure was performed in case the clitoris, or nymphê, grew too large or triggered sexual desire when rubbing against clothing. "On this account, it seemed proper to the Egyptians to remove it before it became greatly enlarged," Aëtius wrote, "especially at that time when the girls were about to be married":

The surgery is performed in this way: Have the girl sit on a chair while a muscled young man standing behind her places his arms below the girl's thighs. Have him separate and steady her legs and whole body. Standing in front and taking hold of the clitoris with a broad-mouthed forceps in his left hand, the surgeon stretches it outward, while with the right hand, he cuts it off at the point next to the pincers of the forceps.The genital area was then cleaned with a sponge, frankincense powder and wine or cold water, and wrapped in linen bandages dipped in vinegar, until the seventh day when calamine, rose petals, date pits or a "genital powder made from baked clay" might be applied.[148]

It is proper to let a length remain from that cut off, about the size of the membrane that's between the nostrils, so as to take away the excess material only; as I have said, the part to be removed is at that point just above the pincers of the forceps. Because the clitoris is a skinlike structure and stretches out excessively, do not cut off too much, as a urinary fistula may result from cutting such large growths too deeply.[147]

Whatever the practice's origins, infibulation became linked to slavery. Mackie cites the Portuguese missionary João dos Santos, who in 1609 wrote of a group inland from Mogadishu who had a "custome to sew up their Females, especially their slaves being young to make them unable for conception, which makes these slaves sell dearer, both for their chastitie, and for better confidence which their Masters put in them." The English explorer William Browne wrote in 1799 that the Egyptians practised excision, and that slaves in that country were infibulated to prevent pregnancy.[149] Thus, Mackie argues, a "practice associated with shameful female slavery came to stand for honor."[150]

Europe and the United States

Isaac Baker Brown "set to work to remove the clitoris whenever he had the opportunity of doing so."[151]

Gynaecologists in 19th-century Europe and the United States removed the clitoris to treat insanity and masturbation.[152] British doctor Robert Thomas suggested clitoridectomy as a cure for nymphomania in 1813.[153] The first reported clitoridectomy in the West, described in The Lancet in 1825, was performed in 1822 in Berlin by Karl Ferdinand von Graefe, on a 15-year-old girl who was masturbating excessively.[154]

Isaac Baker Brown, an English gynaecologist, president of the Medical Society of London, and co-founder in 1845 of St. Mary's Hospital in London, believed that masturbation, or "unnatural irritation" of the clitoris, caused peripheral excitement of the pubic nerve, which led to hysteria, spinal irritation, fits, idiocy, mania and death.[155] He therefore "set to work to remove the clitoris whenever he had the opportunity of doing so," according to his obituary in the Medical Times and Gazette in 1873.[156] Brown performed several clitoridectomies between 1859 and 1866. When he published his views in On the Curability of Certain Forms of Insanity, Epilepsy, Catalepsy, and Hysteria in Females (1866), doctors in London accused him of quackery and expelled him from the Obstetrical Society.[157]

In the United States J. Marion Sims followed Brown's work, and in 1862 slit the neck of a woman's uterus and amputated her clitoris, "for the relief of the nervous or hysterical condition as recommended by Baker Brown," after the patient complained of menstrual pain, convulsions and bladder problems.[158] A. J. Bloch, a surgeon in New Orleans, removed the clitoris of a two-year-old girl who was reportedly masturbating.[159] According to a 1985 paper in the Obstetrical & Gynecological Survey, clitoridectomy was performed in the US into the 1960s to treat hysteria, erotomania and lesbianism.[160]

Opposition

Colonial opposition in Kenya

Muthirigu

Little knives in their sheaths

That they may fight with the church,

The time has come.

Elders (of the church)

When Kenyatta comes

You will be given women's clothes

And you will have to cook him his food.

That they may fight with the church,

The time has come.

Elders (of the church)

When Kenyatta comes

You will be given women's clothes

And you will have to cook him his food.

American missionary Hulda Stumpf (seated, bottom left) was murdered in Kikuyu in 1930 after opposing FGM.

Protestant missionaries in British East Africa (present-day Kenya), began campaigning against FGM in the early 20th century when Dr. John Arthur joined the Church of Scotland Mission (CSM) in Kikuyu. The practice was known by the Kikuyu, the country's main ethnic group, as irua for both girls and boys, and involved excision (Type II) for girls and removal of the foreskin for boys. It was an important ethnic marker, and unexcised Kikuyu women, known as irugu, were outcasts.[162]

Jomo Kenyatta, general secretary of the Kikuyu Central Association and Kenya's first prime minister from 1963, wrote in 1938 that, for the Kikuyu, the institution of FGM was the "conditio sine qua non of the whole teaching of tribal law, religion and morality." No proper Kikuyu man or woman would marry or have sexual relations with someone who was not circumcised. A woman's responsibilities toward the tribe began with her initiation. Her age and place within tribal history was traced to that day, and the group of girls with whom she was cut was named according to current events, an oral tradition that allowed the Kikuyu to track people and events going back hundreds of years.[163]

From 1925, beginning with the CSM mission, several missionary churches declared that FGM was prohibited for African Christians. The CSM announced that Africans practising it would be excommunicated, resulting in hundreds leaving or being expelled.[164] The stand-off turned FGM into a focal point of the Kenyan independence movement; the 1929–1931 period is known in the country's historiography as the female circumcision controversy.[165]

In 1929 the Kenya Missionary Council began referring to FGM as the "sexual mutilation of women," rather than circumcision, and a person's stance toward the practice became a test of loyalty, either to the Christian churches or to the Kikuyu Central Association.[166] Hulda Stumpf, an American missionary with the Africa Inland Mission who opposed FGM in the girls' school she helped to run, was murdered in 1930. Edward Grigg, the governor of Kenya, told the British Colonial Office that the killer, who was never identified, had attempted to circumcise her.[167]

In 1956 the council of male elders (the Njuri Nchecke) in Meru announced a ban on FGM. Over the next three years, as a symbol of defiance, thousands of girls cut each other's genitals with razor blades. The movement came to be known in Meru as Ngaitana ("I will circumcise myself"), because to avoid naming their friends the girls said they had cut themselves. Historian Lynn Thomas describes the episode as significant in the history of FGM because it made clear that its victims were also its perpetrators.[168]

Growth of opposition

The first known non-colonial campaign against FGM began in Egypt in the 1920s, when the Egyptian Doctors' Society called for a ban.[169] There was a parallel campaign in Sudan, run by religious leaders and British women. Infibulation was banned there in 1946, but the law was unpopular and barely enforced.[170] The Egyptian government banned infibulation in state-run hospitals in 1959, but allowed partial clitoridectomy if parents requested it.[171] The UN asked the WHO to investigate FGM that year, but the latter responded that it was not a medical issue.[172]

Feminists took up the issue throughout the 1970s.[173] Egyptian physician Nawal El Saadawi's book, Women and Sex (1972), criticized FGM; the book was banned in Egypt and El Saadawi lost her job as director general of public health.[174] She followed up with a chapter, "The Circumcision of Girls," in The Hidden Face of Eve: Women in the Arab World (1980), which described her own clitoridectomy when she was six years old:

I did not know what they had cut off from my body, and I did not try to find out. I just wept, and called out to my mother for help. But the worst shock of all was when I looked around and found her standing by my side. Yes, it was her, I could not be mistaken, in flesh and blood, right in the midst of these strangers, talking to them and smiling at them, as though they had not participated in slaughtering her daughter just a few moments ago.[175]

| FGM opposition |

|---|

Four years later Austrian-American feminist Fran Hosken published The Hosken Report: Genital and Sexual Mutilation of Females (1979), the first to estimate the global number of women cut. She wrote that 110,529,000 women in 20 African countries had experienced FGM.[177] The figures were speculative, but in several instances consistent with later surveys; Mackie writes that her work was "more informative than the silence that preceded her efforts."[178] Describing FGM as a "training ground for male violence," Hosken accused female practitioners of "participating in the destruction of their own kind."[179] The language caused a rift between Western and African feminists; African women boycotted a session featuring Hosken during the UN's Mid-Decade Conference on Women in Copenhagen in July 1980.[180]

The Inter-African Committee on Traditional Practices Affecting the Health of Women and Children, founded after a seminar in Dakar, Senegal, in 1984, called for an end to the practice, as did the UN's World Conference on Human Rights in Vienna in June 1993. The conference listed FGM as a form of violence against women, marking it as a human-rights violation, rather than a medical issue.[181] Throughout the 1990s and 2000s African governments banned or restricted it. In July 2003 the African Union ratified the Maputo Protocol on the rights of women, article 5 of which supports the elimination of harmful practices, including FGM.[182] By 2013 laws had been passed in 22 of the 27 African countries in which FGM is concentrated, though several fell short of a ban.[183]

Egypt banned FGM in 2007. In 1994 CNN broadcast images of a child undergoing FGM in a barber's shop in Cairo, and in 2007 a child died during an FGM procedure.[184] The death prompted the Al-Azhar Supreme Council of Islamic Research, the country's highest religious authority, to rule that FGM had no basis in Islamic law.[185] The government banned it that year by ministerial decree, and in 2008 added it to the penal code as a criminal offence.[186] The first charges under the new law, against a doctor and a girl's father, were brought in 2014 when the girl died after a procedure.[187] The men were acquitted, but after an appeal the doctor was sentenced in January 2015 to over two years in prison for manslaughter, and the father received a three-month suspended sentence.[188]

United Nations

Mary Karooro Okurut, Uganda's Minister of Gender, Labour and Social Development, speaking at Girl Summit 2014, London, hosted by UNICEF and the UK government

The United Nations General Assembly included FGM in resolution 48/104 in December 1993, the Declaration on the Elimination of Violence Against Women. In 2003 the UN began sponsoring an International Day of Zero Tolerance to Female Genital Mutilation every 6 February.[189] UNICEF began that year to promote an evidence-based social norms approach to the evaluation of intervention, using ideas from game theory about how communities reach decisions, and building on the work of Gerry Mackie about how footbinding had ended in China.[190] In 2005 the UNICEF Innocenti Research Centre in Florence published its first report on FGM.[191]

In 2008 several United Nations bodies, including the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, published a joint statement recognizing FGM as a human-rights violation.[192] In December 2012 the General Assembly passed resolution 67/146, calling for intensified efforts to eliminate it.[15] In July 2014 UNICEF and the UK government co-hosted the first Girl Summit, aimed at ending FGM and child marriage.[193]

UNFPA and UNICEF launched a joint programme in 2007 to reduce FGM by 40 percent within the 0–15 age group, and eliminate it entirely from at least one country. Fifteen countries joined the programme: Djibouti, Egypt, Ethiopia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Senegal and Sudan in 2008; Burkina Faso, Gambia, Uganda and Somalia in 2009; and Eritrea, Mali and Mauritania in 2011.[194] Phase 1 lasted from 2008 to 2013, with a budget of $37 million, over $20 million of it donated by Norway.[195] Phase 2 extends the programme from 2014 to 2017.[196]

By 2013 the programme had organized public declarations of abandonment in 12,753 communities, integrated FGM prevention into pre- and postnatal care in 5,571 health facilities, and trained over 100,000 doctors, nurses and midwives in FGM care and prevention. The programme helped to create alternative rites of passage in Uganda and Kenya, and in Sudan supported the (pre-existing) Saleema initiative. Saleema means "whole" in Arabic; the initiative promotes the term as a desirable description of an uncut woman.[197] The programme noted that anti-FGM law enforcement is weak, and that, even where arrests are made, prosecution may fail because of inadequate collection of evidence.[198] It therefore supported the training of 3,011 personnel in eight countries (Djibouti, Eritrea, Ethiopia, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Kenya, Senegal and Uganda) in how to enforce the laws, and sponsored campaigns to raise awareness of them.[199]

Non-practising countries

As of 2013[update], legislation banning FGM had been passed by 33 countries outside Africa and the Middle East.[200] As a result of immigration the practice spread to Australia, New Zealand, the European Union, North America and Scandinavia, all of which have outlawed it, either entirely or from being performed on minors.[201][202] Sweden outlawed it in 1982, the first Western country to do so.[203] Several former colonial powers, including Belgium, Britain, France and the Netherlands, followed suit, either with new laws or by making clear that it was covered by existing legislation.[204]

Efua Dorkenoo (1949–2014), author of Cutting the Rose (1994) and founder of FORWARD, received an OBE in 1994 for her work against FGM in the UK.[205]

Canada recognized FGM as a form of persecution in July 1994, when it granted refugee status to Khadra Hassan Farah, who had fled Somalia to avoid her daughter being cut.[206] In 1997 it amended section 268 of the Criminal Code of Canada to make a ban on FGM explicit, except where "the person is at least eighteen years of age and there is no resulting bodily harm."[207] As of February 2015[update], there had been no prosecutions.[208]

According to the European Parliament, 500,000 women in Europe had undergone FGM as of March 2009[update].[209] France is known for its tough stance against FGM, reflecting its position that French identity and unity depend on the assimilation of its immigrants.[210] Up to 30,000 women there are thought to have experienced FGM. Colette Gallard, a family-planning counsellor, writes that when FGM was first encountered in France, the reaction was that Westerners ought not to intervene, and it took the deaths of two girls in 1982, one of them three months old, for that attitude to change.[211]

The practice is outlawed by a provision of France's penal code dealing with violence against children.[212] All children under six who were born in France undergo medical examinations that include inspection of the genitals, and doctors are obliged to report FGM.[210] The first civil suit was in 1982 and the first criminal prosecution in 1993.[213] In 1999 a woman was given an eight-year sentence for having performed FGM on 48 girls.[214] By 2014 over 100 parents and two practitioners had been prosecuted in over 40 criminal cases.[212][210]

Around 137,000 women and girls living as permanent residents of England and Wales in 2011 were born in countries where FGM is practised.[215] Although performing FGM on children or adults was outlawed under the Prohibition of Female Circumcision Act 1985, the UK's first prosecution was in 2014.[216] The 1985 Act was replaced by the Female Genital Mutilation Act 2003 and Prohibition of Female Genital Mutilation (Scotland) Act 2005, which added a prohibition on arranging FGM outside the country for British citizens or permanent residents.[217] The United Nations Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women expressed concern in 2013 that there had been no convictions, and asked the government to "ensure the full implementation of its legislation on FGM."[218] The first charges were brought the following year against a physician and another man, after the physician sutured a partially infibulated woman with one stitch to stem bleeding after opening her for childbirth. The prosecution contended that this amounted to reinfibulation. Both men were acquitted in February 2015.[219]

In the United States the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) estimated in 1997 that 168,000 women and girls living there in 1990 had undergone FGM or were at risk.[220] A preliminary, unpublished, CDC study in 2015 reportedly estimates that around 500,000 women and girls in the US have undergone FGM or are likely to undergo it.[221] A Nigerian woman successfully contested deportation in March 1994 on the grounds that her daughters might be cut.[222] In 1996 Fauziya Kasinga from Togo became the first to be granted asylum to escape FGM,[223] although, as of 2006[update], several federal appellate courts have held that a parent cannot receive asylum based on a fear that their child will be subjected to FGM, particularly where the children are legal residents or citizens of the United States.[224]

In 1996 it became illegal under Title 18 of the United States Code, § 116, to perform FGM on minors for non-medical reasons,[225] and the National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year 2013 prohibited transporting a minor out of the country for the purpose of FGM.[226] The American Academy of Pediatrics opposes all forms of the practice. In 2010 it suggested that "pricking or incising the clitoral skin" was a harmless procedure that might satisfy parents, but withdrew the statement after complaints.[227] The first FGM conviction in the US was in 2006, when Khalid Adem, who had emigrated from Ethiopia, was sentenced to ten years after severing his two-year-old daughter's clitoris with a pair of scissors.[228]

Criticism of opposition

Tolerance versus human rights

Anthropologist Eric Silverman wrote in 2004 that FGM had "emerged as one of the central moral topics of contemporary anthropology." Anthropologists have accused FGM eradicationists of cultural colonialism; in turn, the former have been criticized for their moral relativism and failure to defend the idea of universal human rights.[229] According to the opposition's critics, the biological reductionism of the opposition, and the failure to appreciate the practice's cultural context, undermines the practitioners' agency and serves to "other" them – in particular by calling African parents mutilators.[230] Yet Africans who object to the opposition risk appearing to defend FGM.[231]Feminist theorist Obioma Nnaemeka – herself strongly opposed to FGM ("If one is circumcised, it is one too many") – argues that the impact of renaming it female genital mutilation cannot be underestimated:

In this name game, although the discussion is about African women, a subtext of barbaric African and Muslim cultures and the West's relevance (even indispensability) in purging the barbarism marks another era where colonialism and missionary zeal determined what "civilization" was, and figured out how and when to force it on people who did not ask for it.[233]Ugandan law professor Sylvia Tamale argues that early Western opposition to FGM stemmed from a Judeo-Christian judgment that African sexual and family practices – including dry sex, polygyny, bride price and levirate marriage – were primitive and required correction.[234] African feminists "do not condone the negative aspects of the practice," writes Tamale, but "take strong exception to the imperialist, racist and dehumanising infantilization of African women."[234]

The debate has highlighted a tension between anthropology and feminism, with the former's focus on tolerance and the latter's on equal rights for all women. Anthropologist Christine Walley writes that a common trope within the anti-FGM literature has been to present African women as victims of false consciousness participating in their own oppression, a position promoted by several feminists in the 1970s and 1980s, including Fran Hosken, Mary Daly and Hanny Lightfoot-Klein. It prompted the French Association of Anthropologists to issue a statement in 1981, at the height of the early debates, that "a certain feminism resuscitates (today) the moralistic arrogance of yesterday's colonialism."[235]

As an example of the disrespect arguably shown toward women who have undergone FGM, commentators highlight the appropriation of the women's bodies as exhibits. Historian Chima Korieh cites the publication in 1996 of the Pulitzer-prize-winning photographs (above) of a 16-year-old Kenyan girl undergoing FGM. The photographs were published by 12 American newspapers, but according to Korieh the girl had not given permission for the images to be taken, much less published.[236]

Comparison with other procedures

Obioma Nnaemeka argues that the crucial question, broader than FGM, is why the female body is subjected to so much "abuse and indignity" around the world, including in the West.[237] Several authors have drawn a parallel between FGM and cosmetic procedures.[238] Ronán Conroy of the Royal College of Surgeons in Ireland wrote in 2006 that cosmetic genital procedures were "driving the advance of female genital mutilation" by encouraging women to see natural variations as defects.[239] Anthropologist Fadwa El Guindi compares FGM to breast enhancement, in which the maternal function of the breast becomes secondary to men's sexual pleasure.[240] Benoîte Groult made a similar point in 1975, citing FGM and cosmetic surgery as sexist and patriarchal.[241]

Martha Nussbaum argues that a key moral and legal issue with FGM is that it is mostly conducted on children using physical force.

Carla Obermeyer maintains that FGM may be conducive to women's well-being within their communities in the same way that rhinoplasty and male circumcision may help people elsewhere.[242] In Egypt, despite the 2007 ban, women wanting FGM for their daughters discuss the need for amalyet tajmeel (cosmetic surgery) to remove what is viewed as excess genital tissue for a more acceptable appearance.[243]

The WHO does not cite procedures such as labiaplasty and clitoral hood reduction as examples of FGM, but its definition aims to avoid loopholes, so several elective practices on adults do fall within its categories.[244] Some of the laws banning FGM, including in Canada and the US, focus only on minors. Several countries, including Sweden and the UK, have banned it regardless of consent, and the legislation would seem to cover cosmetic procedures. Sweden, for example, has banned "[o]perations on the external female genital organs which are designed to mutilate them or produce other permanent changes in them ... regardless of whether consent to this operation has or has not been given."[245] Gynaecologist Birgitta Essén and anthropologist Sara Johnsdotter note that it seems the law distinguishes between Western and African genitals, and deems only African women (such as those seeking reinfibulation after childbirth) unfit to make their own decisions.[246]

Arguing against suggested similarities between FGM and dieting or body shaping, philosopher Martha Nussbaum writes that a key difference is that FGM is mostly conducted on children using physical force. She argues that the distinction between social pressure and physical force is morally and legally salient, comparable to the distinction between seduction and rape. She argues further that the literacy of women in practising countries is generally poorer than in developed nations, and that this reduces their ability to make informed choices.[247]

Several commentators maintain that children's rights are violated with the genital alteration of intersex children, who are born with anomalies that physicians choose to correct. Legal scholars Nancy Ehrenreich and Mark Barr write that thousands of these procedures take place every year in the United States, and say that they are medically unnecessary, more extensive than FGM, and have more serious physical and mental consequences. They attribute the silence of anti-FGM campaigners about intersex procedures to white privilege and a refusal to acknowledge that "similar unnecessary and harmful genital cutting occurs in their own backyards."[248]

![Percentage of women aged 15–49 with FGM in the 29 countries in which it is concentrated (UNICEF, November 2014).[5] Click here for a more detailed map of Africa.](http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/e/e7/FGM_prevalence_UNICEF_2015.svg/350px-FGM_prevalence_UNICEF_2015.svg.png)