| Thomas Hobbes | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

5 April 1588 Westport, Wiltshire, England |

| Died |

4 December 1679 (aged 91) Derbyshire, England |

| Alma mater | Magdalen Hall, Oxford |

| Era | 17th-century philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Social contract, classical realism, empiricism, determinism, materialism, ethical egoism |

Main interests

| Political philosophy, history, ethics, geometry |

Notable ideas

| Modern founder of the social contract tradition; life in the state of nature is "solitary, poor, nasty, brutish and short"; bellum omnium contra omnes |

Thomas Hobbes (/hɒbz/; 5 April 1588 – 4 December 1679), in some older texts Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury, was an English philosopher who is considered one of the founders of modern political philosophy. Hobbes is best known for his 1651 book Leviathan, which expounded an influential formulation of social contract theory. In addition to political philosophy, Hobbes also contributed to a diverse array of other fields, including history, jurisprudence, geometry, the physics of gases, theology, ethics, and general philosophy.

Though on rational grounds a champion of absolutism for the sovereign, Hobbes also developed some of the fundamentals of European liberal thought: the right of the individual; the natural equality of all men; the artificial character of the political order (which led to the later distinction between civil society and the state); the view that all legitimate political power must be "representative" and based on the consent of the people; and a liberal interpretation of law that leaves people free to do whatever the law does not explicitly forbid.[6] His understanding of humans as being matter and motion, obeying the same physical laws as other matter and motion, remains influential; and his account of human nature as self-interested cooperation, and of political communities as being based upon a "social contract" remains one of the major topics of political philosophy.

Early life and education

At university, Hobbes appears to have followed his own curriculum; he was "little attracted by the scholastic learning". He did not complete his B.A. degree until 1608, but he was recommended by Sir James Hussey, his master at Magdalen, as tutor to William, the son of William Cavendish, Baron of Hardwick (and later Earl of Devonshire), and began a lifelong connection with that family.[13]

Hobbes became a companion to the younger William and they both took part in a grand tour of Europe in 1610. Hobbes was exposed to European scientific and critical methods during the tour, in contrast to the scholastic philosophy that he had learned in Oxford. His scholarly efforts at the time were aimed at a careful study of classic Greek and Latin authors, the outcome of which was, in 1628, his great translation of Thucydides' History of the Peloponnesian War, the first translation of that work into English from a Greek manuscript. It has been argued that three of the discourses in the 1620 publication known as Horea Subsecivae: Observations and Discourses also represent the work of Hobbes from this period.[14]

Although he associated with literary figures like Ben Jonson and briefly worked as Francis Bacon's amanuensis, he did not extend his efforts into philosophy until after 1629. His employer Cavendish, then the Earl of Devonshire, died of the plague in June 1628. The widowed countess dismissed Hobbes, but he soon found work, again as a tutor, this time to Gervase Clifton, the son of Sir Gervase Clifton, 1st Baronet. This task, chiefly spent in Paris, ended in 1631 when he again found work with the Cavendish family, tutoring William, the eldest son of his previous pupil. Over the next seven years, as well as tutoring, he expanded his own knowledge of philosophy, awakening in him curiosity over key philosophic debates. He visited Florence in 1636 and was later a regular debater in philosophic groups in Paris, held together by Marin Mersenne.

In Paris

Thomas Hobbes

Hobbes's first area of study was an interest in the physical doctrine of motion and physical momentum. Despite his interest in this phenomenon, he disdained experimental work as in physics. He went on to conceive the system of thought to the elaboration of which he would devote his life. His scheme was first to work out, in a separate treatise, a systematic doctrine of body, showing how physical phenomena were universally explicable in terms of motion, at least as motion or mechanical action was then understood. He then singled out Man from the realm of Nature and plants. Then, in another treatise, he showed what specific bodily motions were involved in the production of the peculiar phenomena of sensation, knowledge, affections and passions whereby Man came into relation with Man. Finally he considered, in his crowning treatise, how Men were moved to enter into society, and argued how this must be regulated if Men were not to fall back into "brutishness and misery". Thus he proposed to unite the separate phenomena of Body, Man, and the State.[citation needed]

Hobbes came home, in 1637, to a country riven with discontent, which disrupted him from the orderly execution of his philosophic plan. However, by the end of the Short Parliament in 1640, he had written a short treatise called The Elements of Law, Natural and Politic. It was not published and only circulated as a manuscript among his acquaintances. A pirated version, however, was published about ten years later. Although it seems that much of The Elements of Law was composed before the sitting of the Short Parliament, there are polemical pieces of the work that clearly mark the influences of the rising political crisis. Nevertheless, many (though not all) elements of Hobbes's political thought were unchanged between The Elements of Law and Leviathan, which demonstrates that the events of the English Civil War had little effect on his contractarian methodology. However, the arguments in Leviathan were modified from The Elements of Law when it came to the necessity of consent in creating political obligation. Namely, Hobbes wrote in The Elements of Law that Patrimonial kingdoms were not necessarily formed by the consent of the governed, while in Leviathan he argued that they were. This was perhaps a reflection either of Hobbes's thoughts about the engagement controversy or of his reaction to treatises published by Patriarchalists, such as Sir Robert Filmer, between 1640 and 1651.[citation needed]

When in November 1640 the Long Parliament succeeded the Short, Hobbes felt that he was in disfavour due to the circulation of his treatise and fled to Paris. He did not return for 11 years. In Paris, he rejoined the coterie around Mersenne and wrote a critique of the Meditations on First Philosophy of Descartes, which was printed as third among the sets of "Objections" appended, with "Replies" from Descartes, in 1641. A different set of remarks on other works by Descartes succeeded only in ending all correspondence between the two.

Hobbes also extended his own works in a way, working on the third section, De Cive, which was finished in November 1641. Although it was initially only circulated privately, it was well received, and included lines of argumentation that were repeated a decade later in Leviathan. He then returned to hard work on the first two sections of his work and published little except a short treatise on optics (Tractatus opticus) included in the collection of scientific tracts published by Mersenne as Cogitata physico-mathematica in 1644. He built a good reputation in philosophic circles and in 1645 was chosen with Descartes, Gilles de Roberval and others to referee the controversy between John Pell and Longomontanus over the problem of squaring the circle.

Civil war in England

The English Civil War broke out in 1642,[15] and when the royalist cause began to decline in mid-1644,[16] the king's supporters fled to Europe.[17] Many came to Paris and were known to Hobbes. This revitalised Hobbes's political interests and the De Cive was republished and more widely distributed. The printing began in 1646 by Samuel de Sorbiere through the Elsevier press at Amsterdam with a new preface and some new notes in reply to objections.In 1647, Hobbes took up a position as mathematical instructor to the young Charles, Prince of Wales,[18] who had come over from Jersey around July. This engagement lasted until 1648 when Charles went to Holland.

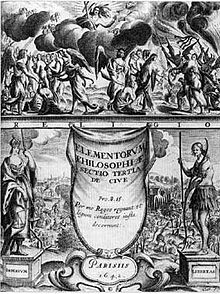

Frontispiece from De Cive (1642)

The company of the exiled royalists led Hobbes to produce Leviathan, which set forth his theory of civil government in relation to the political crisis resulting from the war. Hobbes compared the State to a monster (leviathan) composed of men, created under pressure of human needs and dissolved by civil strife due to human passions. The work closed with a general "Review and Conclusion", in response to the war, which answered the question: Does a subject have the right to change allegiance when a former sovereign's power to protect is irrevocably lost?

During the years of composing Leviathan, Hobbes remained in or near Paris. In 1647, a serious illness that nearly killed him disabled him for six months. On recovering, he resumed his literary task and completed it by 1650. Meanwhile, a translation of De Cive was being produced; scholars disagree about whether it was Hobbes who translated it.

In 1650, a pirated edition of The Elements of Law, Natural and Politic was published.[19] It was divided into two small volumes (Human Nature, or the Fundamental Elements of Policie and De corpore politico, or the Elements of Law, Moral and Politick).[20] In 1651, the translation of De Cive was published under the title Philosophicall Rudiments concerning Government and Society. Meanwhile, the printing of the greater work proceeded, and finally appeared in mid-1651, titled Leviathan, or the Matter, Forme, and Power of a Common Wealth, Ecclesiasticall and Civil. It had a famous title-page engraving depicting a crowned giant above the waist towering above hills overlooking a landscape, holding a sword and a crozier and made up of tiny human figures.

The work had immediate impact. Soon, Hobbes was more lauded and decried than any other thinker of his time. The first effect of its publication was to sever his link with the exiled royalists, who might well have killed him. The secularist spirit of his book greatly angered both Anglicans and French Catholics. Hobbes appealed to the revolutionary English government for protection and fled back to London in winter 1651. After his submission to the Council of State, he was allowed to subside into private life in Fetter Lane.

Leviathan

Frontispiece of Leviathan

In Leviathan, Hobbes set out his doctrine of the foundation of states and legitimate governments and creating an objective science of morality. This gave rise to social contract theory. Leviathan was written during the English Civil War; much of the book is occupied with demonstrating the necessity of a strong central authority to avoid the evil of discord and civil war.

Beginning from a mechanistic understanding of human beings and their passions, Hobbes postulates what life would be like without government, a condition which he calls the state of nature. In that state, each person would have a right, or license, to everything in the world. This, Hobbes argues, would lead to a "war of all against all" (bellum omnium contra omnes). The description contains what has been called one of the best known passages in English philosophy, which describes the natural state humankind would be in, were it not for political community:[21]

In such condition, there is no place for industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain: and consequently no culture of the earth; no navigation, nor use of the commodities that may be imported by sea; no commodious building; no instruments of moving, and removing, such things as require much force; no knowledge of the face of the earth; no account of time; no arts; no letters; no society; and which is worst of all, continual fear, and danger of violent death; and the life of man, solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.[22]In such a state, people fear death, and lack both the things necessary to commodious living, and the hope of being able to toil to obtain them. So, in order to avoid it, people accede to a social contract and establish a civil society. According to Hobbes, society is a population and a sovereign authority, to whom all individuals in that society cede some rights for the sake of protection. Any power exercised by this authority cannot be resisted, because the protector's sovereign power derives from individuals' surrendering their own sovereign power for protection. The individuals are thereby the authors of all decisions made by the sovereign.[23] "he that complaineth of injury from his sovereign complaineth that whereof he himself is the author, and therefore ought not to accuse any man but himself, no nor himself of injury because to do injury to one's self is impossible". There is no doctrine of separation of powers in Hobbes's discussion.[24] According to Hobbes, the sovereign must control civil, military, judicial and ecclesiastical powers, even the words.[25]

Opposition

John Bramhall

In 1654 a small treatise, Of Liberty and Necessity, directed at Hobbes, was published by Bishop John Bramhall.[26] Bramhall, a strong Arminian, had met and debated with Hobbes and afterwards wrote down his views and sent them privately to be answered in this form by Hobbes. Hobbes duly replied, but not for publication. However, a French acquaintance took a copy of the reply and published it with "an extravagantly laudatory epistle".[citation needed] Bramhall countered in 1655, when he printed everything that had passed between them (under the title of A Defence of the True Liberty of Human Actions from Antecedent or Extrinsic Necessity). In 1656, Hobbes was ready with The Questions concerning Liberty, Necessity and Chance, in which he replied "with astonishing force"[citation needed] to the bishop. As perhaps the first clear exposition of the psychological doctrine of determinism, Hobbes's own two pieces were important in the history of the free-will controversy. The bishop returned to the charge in 1658 with Castigations of Mr Hobbes's Animadversions, and also included a bulky appendix entitled The Catching of Leviathan the Great Whale.John Wallis

Hobbes opposed the existing academic arrangements, and assailed the system of the original universities in Leviathan. He went on to publish De Corpore, which contained not only tendentious views on mathematics but also an erroneous proof of the squaring of the circle. This all led mathematicians to target him for polemics and sparked John Wallis to become one of his most persistent opponents. From 1655, the publishing date of De Corpore, Hobbes and Wallis went round after round trying to disprove each other's positions. After years of debate, the spat over proving the squaring of the circle gained such notoriety that it has become one of the most infamous feuds in mathematical history.Atheism

Hobbes has been accused of atheism, or (in the case of Bramhall) of teachings that could lead to atheism. This was an important accusation, and Hobbes himself wrote, in his answer to Bramhall's The Catching of Leviathan, that "atheism, impiety, and the like are words of the greatest defamation possible".[27] Hobbes always defended himself from such accusations.[28] In more recent times also, much has been made of his religious views by scholars such as Richard Tuck and J. G. A. Pocock, but there is still widespread disagreement about the exact significance of Hobbes's unusual views on religion.As Martinich has pointed out, in Hobbes's time the term "atheist" was often applied to people who believed in God but not in divine providence, or to people who believed in God but also maintained other beliefs that were inconsistent with such belief. He says that this "sort of discrepancy has led to many errors in determining who was an atheist in the early modern period".[29] In this extended early modern sense of atheism, Hobbes did take positions that strongly disagreed with church teachings of his time. For example, he argued repeatedly that there are no incorporeal substances, and that all things, including human thoughts, and even God, heaven, and hell are corporeal, matter in motion. He argued that "though Scripture acknowledge spirits, yet doth it nowhere say, that they are incorporeal, meaning thereby without dimensions and quantity".[30] (In this view, Hobbes claimed to be following Tertullian, whose views were not condemned in the First Council of Nicaea.) Like John Locke, he also stated that true revelation can never disagree with human reason and experience,[31] although he also argued that people should accept revelation and its interpretations for the reason that they should accept the commands of their sovereign, in order to avoid war.

Later life

Tomb of Thomas Hobbes in St John the Baptist's Church, Ault Hucknall in Derbyshire

In 1658, Hobbes published the final section of his philosophical system, completing the scheme he had planned more than 20 years before. De Homine consisted for the most part of an elaborate theory of vision. The remainder of the treatise dealt cursorily with some of the topics more fully treated in the Human Nature and the Leviathan. In addition to publishing some controversial writings on mathematics and physics, Hobbes also continued to produce philosophical works. From the time of the Restoration, he acquired a new prominence; "Hobbism" became a byword for all that respectable society ought to denounce. The young king, Hobbes' former pupil, now Charles II, remembered Hobbes and called him to the court to grant him a pension of £100.

The king was important in protecting Hobbes when, in 1666, the House of Commons introduced a bill against atheism and profaneness. That same year, on 17 October 1666, it was ordered that the committee to which the bill was referred "should be empowered to receive information touching such books as tend to atheism, blasphemy and profaneness... in particular... the book of Mr. Hobbes called the Leviathan".[32] Hobbes was terrified at the prospect of being labelled a heretic, and proceeded to burn some of his compromising papers. At the same time, he examined the actual state of the law of heresy. The results of his investigation were first announced in three short Dialogues added as an Appendix to his Latin translation of Leviathan, published in Amsterdam in 1668. In this appendix, Hobbes aimed to show that, since the High Court of Commission had been put down, there remained no court of heresy at all to which he was amenable, and that nothing could be heresy except opposing the Nicene Creed, which, he maintained, Leviathan did not do.

The only consequence that came of the bill was that Hobbes could never thereafter publish anything in England on subjects relating to human conduct. The 1668 edition of his works was printed in Amsterdam because he could not obtain the censor's licence for its publication in England. Other writings were not made public until after his death, including Behemoth: the History of the Causes of the Civil Wars of England and of the Counsels and Artifices by which they were carried on from the year 1640 to the year 1662. For some time, Hobbes was not even allowed to respond, whatever his enemies tried. Despite this, his reputation abroad was formidable, and noble or learned foreigners who came to England never forgot to pay their respects to the old philosopher.

His final works were an autobiography in Latin verse in 1672, and a translation of four books of the Odyssey into "rugged" English rhymes that in 1673 led to a complete translation of both Iliad and Odyssey in 1675.

Death

In October 1679 Hobbes suffered a bladder disorder, and then a paralytic stroke, from which he died on 4 December 1679, aged 91.[33] His last words were said to have been, "A great leap in the dark," uttered in his final conscious moments.[34] His body was interred in St John the Baptist's Church, Ault Hucknall, in Derbyshire.[35]Works (Bibliography)

- 1602. Latin translation of Euripides' Medea (lost).

- 1620. Three of the discourses in the Horae Subsecivae: Observation and Discourses (A Discourse of Tacitus, A Discourse of Rome, and A Discourse of Laws).[36]

- 1626. De Mirabilis Pecci, Being the Wonders of the Peak in Darby-shire, (a poem first published in 1636)

- 1629. Eight Books of the Peloponnesian Warre, translation with an Introduction of Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War

- 1630. A Short Tract on First Principles, British Museum, Harleian MS 6796, ff. 297–308: critical edition with commentary and French translation by Jean Bernhardt: Court traité des premiers principes, Paris, PUF, 1988 (authorship doubtful: this work is attributed by some critics to Robert Payne).[37]

- 1637 A Briefe of the Art of Rhetorique (in Molesworth's edition the title is The Whole Art of Rhetoric). A new edition has been edited by John T. Harwood: The Rhetorics of Thomas Hobbes and Bernard Lamy, Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 1986. (Authorship probable: While Karl Schuhmann firmly rejects the attribution of this work to Hobbes, disagreeing with Quentin Skinner, who has come to agree with Schuhmann, a preponderance of scholarship disagrees with Schuhmann's idiosyncratic assessment.)[38]

- 1639. Tractatus opticus II (British Library, Harley MS 6796, ff. 193–266; first complete edition 1963)[39]

- 1640. Elements of Law, Natural and Politic (circulated only in handwritten copies, first printed edition, without Hobbes's permission in 1650)

- 1641. Objectiones ad Cartesii Meditationes de Prima Philosophia (Third series of Objections)

- 1642. Elementorum Philosophiae Sectio Tertia de Cive (Latin, first limited edition)

- 1643. De Motu, Loco et Tempore (first edition 1973 with the title: Thomas White's De Mundo Examined)[40]

- 1644. Part of the Praefatio to Mersenni Ballistica (in F. Marini Mersenni minimi Cogitata physico-mathematica. In quibus tam naturae quàm artis effectus admirandi certissimis demonstrationibus explicantur)

- 1644. Opticae, liber septimus, (written in 1640) in Universae geometriae mixtaeque mathematicae synopsis, edited by Marin Mersenne (reprinted by Molesworth in OL V pp. 215–48 with the title Tractatus Opticus)

- 1646. A Minute or First Draught of the Optiques (Harley MS 3360; Molesworth published only the dedication to Cavendish and the conclusion in EW VII, pp. 467–71)

- 1646. Of Liberty and Necessity (published without the permission of Hobbes in 1654)

- 1647. Elementa Philosophica de Cive (second expanded edition with a new Preface to the Reader)

- 1650. Answer to Sir William Davenant's Preface before Gondibert

- 1650. Human Nature: or The fundamental Elements of Policie (first thirteen chapters of The Elements of Law, Natural and Politic, published without Hobbes's authorisation)

- 1650. Pirated edition of The Elements of Law, Natural and Politic, repackaged to include two parts:

- Human Nature, or the Fundamental Elements of Policie (chapters 14–19 of Part One of the Elements of 1640)

- De Corpore Politico (Part Two of the Elements of 1640)

- 1651. Philosophical Rudiments concerning Government and Society (English translation of De Cive)[41]

- 1651. Leviathan, or the Matter, Forme, and Power of a Commonwealth, Ecclesiasticall and Civil

- 1654. Of Libertie and Necessitie, a Treatise

- 1655. De Corpore (Latin)

- 1656. Elements of Philosophy, The First Section, Concerning Body (anonymous English translation of De Corpore)

- 1656. Six Lessons to the Professor of Mathematics

- 1656. The Questions concerning Liberty, Necessity and Chance (reprint of Of Libertie and Necessitie, a Treatise, with the addition of Bramhall's reply and Hobbes's reply to Bramahall's reply)

- 1657. Stigmai, or Marks of the Absurd Geometry, Rural Language, Scottish Church Politics, and Barbarisms of John Wallis

- 1658. Elementorum Philosophiae Sectio Secunda De Homine

- 1660. Examinatio et emendatio mathematicae hodiernae qualis explicatur in libris Johannis Wallisii

- 1661. Dialogus physicus, sive De natura aeris

- 1662. Problematica Physica (translated in English in 1682 as Seven Philosophical Problems)

- 1662. Seven Philosophical Problems, and Two Propositions of Geometru (published posthumously)

- 1662. Mr. Hobbes Considered in his Loyalty, Religion, Reputation, and Manners. By way of Letter to Dr. Wallis (English autobiography)

- 1666. De Principis & Ratiocinatione Geometrarum

- 1666. A Dialogue between a Philosopher and a Student of the Common Laws of England (published in 1681)

- 1668. Leviathan (Latin translation)

- 1668. An Answer to a Book published by Dr. Bramhall (published in 1682)

- 1671. Three Papers Presented to the Royal Society Against Dr. Wallis. Together with Considerations on Dr. Wallis his Answer to them

- 1671. Rosetum Geometricum, sive Propositiones Aliquot Frustra antehac tentatae. Cum Censura brevi Doctrinae Wallisianae de Motu

- 1672. Lux Mathematica. Excussa Collisionibus Johannis Wallisii

- 1673. English translation of Homer's Iliad and Odyssey

- 1674. Principia et Problemata Aliquot Geometrica Antè Desperata, Nunc breviter Explicata & Demonstrata

- 1678. Decameron Physiologicum: Or, Ten Dialogues of Natural Philosophy

- 1679. Thomae Hobbessii Malmesburiensis Vita. Authore seipso (Latin autobiography, translated into English in 1680)

- Posthumous works

- 1680. An Historical Narration concerning Heresie, And the Punishment thereof

- 1681. Behemoth, or The Long Parliament (written in 1668, unpublished at the request of the King, first pirated edition 1679)

- 1682. Seven Philosophical Problems (English translation of Problematica Physica, 1662)

- 1682. A Garden of Geometrical Roses (English translation of Rosetum Geometricum, 1671)

- 1682. Some Principles and Problems in Geometry (English translation of Principia et Problemata, 1674)

- 1688. Historia Ecclesiastica Carmine Elegiaco Concinnata

- Complete editions

- Thomae Hobbes Malmesburiensis Opera Philosophica quae Latina Scripsit, Studio et labore Gulielmi Molesworth, (Londini, 1839–1845). 5 volumes. Reprint: Aalen, 1966 (= OL).

- Volume I. Elementorum Philosophiae I: De Corpore

- Volume II. Elementorum Philosophiae II and III: De Homine and De Cive

- Volume III. Latin version of Leviathan.

- Volume IV. Various concerning mathematics, geometry and physics.

- Volume V. Various short works.

- The English Works of Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury; Now First Collected and Edited by Sir William Molesworth, Bart., (London: Bohn, 1839–45). 11 volumes. Reprint London, 1939-–; reprint: Aalen, 1966 (= EW).

- Volume 1. De Corpore translated from Latin to English.

- Volume 2. De Cive.

- Volume 3. The Leviathan

- Volume 4.

- TRIPOS ; in Three Discourses:

- I. Human Nature, or the Fundamental Elements of Policy

- II. De Corpore Politico, or the Elements of Law

- III. Of Liberty and Necessity

- An Answer to Bishop Bramhall's Book, called "The Catching of the Leviathan"

- An Historical Narration concerning Heresy, and the Punishment thereof

- Considerations upon the Reputation, Loyalty, Manners, and Religion of Thomas Hobbes

- Answer to Sir William Davenant's Preface before "Gondibert"

- Letter to the Right Honourable Edward Howard

- Volume 5. The Questions concerning Liberty, Necessity and Chance, clearly stated and debated between Dr Bramhall Bishop of Derry and Thomas Hobbes of Malmesbury.

- Volume 6.

- A Dialogue Between a Philosopher & a Student of the Common Laws of England

- A Dialogue of the Common Law

- Behemoth: the History of the Causes of the Civil Wars of England, and of the Counsels and Artifices By Which They Were Carried On From the Year 1640 to the Year 1660

- The Whole Art of Rhetoric (Hobbes's translation of his own Latin summary of Aristotle's Rhetoric published in 1637 with the title A Briefe of the Art of Rhetorique)

- The Art of Rhetoric Plainly Set Forth. With Pertinent Examples For the More Easy Understanding and Practice of the Same (this work is not of Hobbes but by Dudley Fenner, The Artes of Logike and Rethorike, 1584)

- The Art of Sophistry

- Seven Philosophical Problems

- Decameron Physiologicum

- Proportion of a straight line to half the arc of a quadrant

- Six lessons to the Savilian Professors of the Mathematics

- ΣΤΙΓΜΑΙ, or Marks of the absurd Geometry etc. of Dr Wallis

- Extract of a letter from Henry Stubbe

- Three letters presented to the Royal Society against Dr Wallis

- Considerations on the answer of Dr Wallis

- Letters and other pieces

- Volume 8 and 9. The Peloponnesian War by Thucydides, translated into English by Hobbes.

- Volume 10. The Iliad, and The Odyssey, translated by Hobbes into English

- Volume 11. Index.

- Posthumous works not included in the Molesworth editions

- The Elements of Law, Natural and Politic, edited with a preface and critical notes by Ferdinand Tönnies, London, 1889 (first complete edition).

- Short Tract on First Principles, in The Elements of Law, Natural and Politic, Appendix I, pp. 193–210.[42] (this work is now attributed to Robert Payne).[43]

- Tractatus opticus II (1639, British Library, Harley MS 6796, ff. 193–266): first partial edition in The Elements of Law, Natural and Politic, Appendix II, pp. 211–26; first complete edition (but omitting the diagrams) by Franco Alessio, Rivista critica di storia della filosofia, 18, 1963, pp. 147–228.

- Critique du 'De mundo' de Thomas White, edited by Jean Jacquot and Harold Whitmore Jones, Paris, 1973, with three appendixes:

- De Motibus Solis, Aetheris & Telluris (pp. 439–47: a Latin poem on the movement of the Earth).

- Notes in English on an ancient redaction of some chapters of De Corpore (July 1643; pp. 448–60: MS 5297, National Library of Wales).

- Notes for the Logica and Philosophia prima of the De Corpore (pp. 461–513: Chatsworth MS A10 and the notes of Charles Cavendish on a draft of the De Corpore: British Library, Harley MS 6083).

- Of the Life and History of Thucydides, in Hobbes's Thucydides, edited by Richard Schlatter, New Brunswick, pp. 10–27, 1975.

- Three Discourses: a Critical Modern Edition of Newly Identified Work of the Young Hobbes (TD), edited by Noel B. Reynolds and Arlene Saxonhouse, Chicago, 1975.

- A Discourse upon the Beginning of Tacitus, in TD, pp. 31–67.

- A Discourse of Rome, in TD, pp. 71–102.

- A Discourse of Law, in TD, pp. 105–19.

- Thomas Hobbes' A Minute or First Draught of the Optiques (British Library, Harley MS 3360). Critical Edition by Elaine C. Stroud, Ph.D. dissertation, University of Wisconsin-Madison, 1983.

- Of Passions, Edition of the unpublished manuscript Harley 6093 by Anna Minerbi Belgrado, in: Rivista di storia della filosofia, 43, 1988, pp. 729–38.

- The Correspondence of Thomas Hobbes, edited by Noel Malcolm, Oxford: the Clarendon Edition, vol. 6–7, 1994 (I: 1622–1659; II: 1660–1679).

- Translations in modern English

- De Corpore, Part I. Computatio Sive Logica. Edited with an Introductory Essay by L C. Hungerland and G. R. Vick. Translation and Commentary by A. Martinich. New York: Abaris Books, 1981.

- Thomas White's De mundo Examined, translation by H. W. Jones, Bradford: Bradford University Press, 1976 (the appendixes of the Latin edition (1973) are not enclosed).

- New critical editions of Hobbes' works (in progress)

- Clarendon Edition of the Works of Thomas Hobbes, Oxford: Clarendon Press (10 volumes published of 27 planned).

- Traduction des œuvres latines de Hobbes, under the direction of Yves Charles Zarka, Paris: Vrin (5 volumes published of 17 planned).